By Charles Whiting

By early autumn, he was taking 60 pills a day. They ranged from “speed” to the poison strychnine. He took pills to make him wake up; he took pills to make him sleep. Although to his entourage he seemed to have retained his old willpower and energy, it was really the tablets that kept him going.

By now, Hitler’s secretaries noticed that his knee shook all the time. Sometimes he had to control the shaking in his left knee with his right hand. What his adoring young female secretaries did not know was that his knee continued to tremble even when he was in bed. There, too, he was plagued by stomach cramps. What the secretaries did notice—they could not help but do so—was that the Führer passed gas all the time due to his vegetarian diet and weight-reducing tablets. His doctors—there were four of them—called it “meteorism” from the violence of his constant breaking of wind. The female secretaries called it something else.

The July 20, 1944 bomb attempt on his life had not helped his condition much. His eardrums had been injured, and he no longer heard well. He could not shave himself because his hands trembled so much. His sinus headaches were beginning to keep him awake all night. So, he begged his doctors to give him cocaine injections to keep the pain at bay, commenting, “I hope you are not making an addict out of me.”

In truth, they had done that long ago. He was now subject to hallucinations and giddy spells, snarling angrily at the medics until he lost his voice. Then, every one of the toadies at his court started talking in whispers as he was now forced to do.

In the first week of September 1944, the Führer took to his bed. There, the hypochondriac that he had become studied medical textbooks and examined the various instruments his doctors left behind. Otherwise, he spent hours just staring at the ceiling of his bunker bedroom. It was as if he had forgotten the war and the fact that his enemies were coming ever closer to Germany’s frontiers, from both east and west.

Suddenly, however, completely out of the blue, he asked his cunning-faced chief of operations, Col. Gen. Alfred Jodl, to bring him a large—scale map of Germany’s western frontier. Together, the two men studied it as they had done years before when they had mounted their adventurous attack westward against the Anglo-French armies.

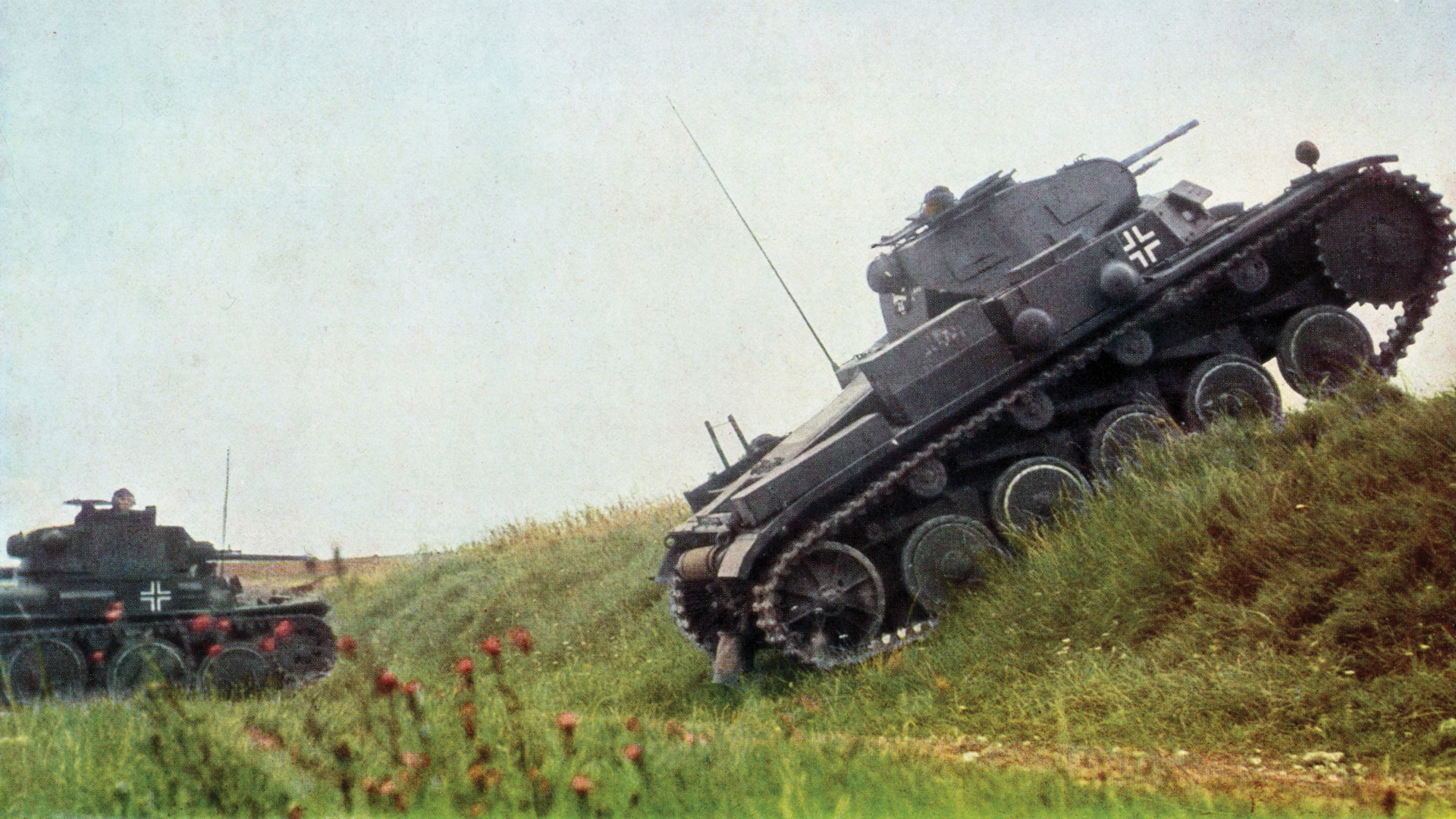

Jodl knew the Führer was very ill. His doctors were already talking of cancer and Parkinson’s disease. Yet, this day the sick leader seemed to possess new energy as he pored over the map of the German Eifel region and across the border into nearby Belgium and Luxembourg, the same terrain through which the Wehrmacht had launched its victorious blitzkrieg in 1940.

Peering through the nickel-framed glasses in which it was forbidden to photograph him, he went into detail, examining the country roads that led through the bunkers of the Westwall (Siegfried Line) into the enemy countries now being rapidly taken over by the victorious Western Allies. That September day, he established a new SS panzer army in Germany, giving command of the Sixth SS Panzer Army, as it was to be called, to the old party bullyboy SS General Sepp Dietrich. Obviously he had a new plan!

A week later, Hitler attended his regular war conference. On September 16, 1944, he listened somewhat apathetically to the routine details of the latest situation on the Eastern Front. When the situation report was over, Hitler asked certain senior officers to remain behind. Among them was a relatively unknown Luftwaffe general, General Werner Kreipe, who represented “Fat Hermann” as the gross Luftwaffe head, Hermann Göring, was known behind his back.

Kreipe’s Illegal Secret Diary

Kreipe, who knew that both the Luftwaffe and its commander had fallen into disfavor at Hitler’s court, did something that day which could have cost him his life if he had been discovered. He kept a diary record of the proceedings, something which was totally illegal. He recorded in that diary that Jodl explained there were currently 55 German divisions on the Western Front confronting 96 enemy divisions. Almost in passing, Jodl mentioned that the Germans were presently enjoying a breathing spell in the Eifel and Ardennes Forest sector, where 80 miles of front were being held by a mere four U.S. divisions.

Suddenly, at the mention of the Ardennes, Hitler came to life. He raised his hand dramatically and, as Kreipe’s diary states: “The Führer interrupts Jodl. He had resolved to mount a counterattack from the Ardennes, with Antwerp as the target . . . the present front can easily be held. Our own attacking force will consist of thirty new Volksgrenadier divisions and new panzer divisions, plus panzer divisions from the Eastern Front. Split the British and American armies at their seam, then a new Dunkirk! . . . Our offensive will begin in a bad-weather period when the enemy air force is grounded . . . [Field Marshal Gerd] von Rundstedt will take command.” Finally a new and seemingly invigorated Hitler ordered the select few senior officers present to keep this secret plan to themselves “on pain of death.”

On the same day Hitler announced to his generals what would be known to them as the Rundstedt Offensive, though the aged, cognac-drinking field marshal always scornfully disclaimed any responsibility for it, and to the Allies as the Battle of the Bulge, a whole American corps had crossed the German border in Eifel-Ardennes region. Three U.S. divisions, the 4th and 28th Infantry and the 5th Armored, had already battered their way through the Westwall and seemed well on their way to the Rhine River, Germany’s last great natural defensive barrier. Indeed, so dangerous did the situation appear on the Western Front that von Rundstedt, who had made that great blitzkrieg of 1940 possible, needed personally to take over command and ensure the Americans were driven back.

What then do we make of Hitler’s decision to attack in the West under such circumstances? His Reich was already under intense pressure from East and West. His people were weary, and 70 percent of Germany’s great cities had suffered tremendous damage due to years of Allied bombing. Were these the fanciful delusions of a madman, or the sick fantasy of a very ill leader, who suffered from drug-induced hallucinations? Was this some kind of megalomania, fed by sycophants and courtiers who pandered to the Führer’s every crazy notion?

In this context, it might be noted that all great men often have seemed to their critics to have done things that were not quite normal or even damned abnormal. What do we say, for instance, about Churchill, Hitler’s contemporary? Back in 1940, when the British Prime Minister had first tried to establish his “special relationship” with the United States, President Franklin D. Roosevelt had called him a “drunken bum.” The President had also commissioned an investigation by the FBI to find out more about Churchill’s drinking habits, which included whisky for breakfast and various other strong waters for the rest of the day.

As Churchill admitted cheerfully himself, “I must point out that my rule of life prescribes as an absolute sacred rite, smoking cigars and also drinking alcohol before, after, and, if need be, during all meals and in the intervals between them.”

How could one rely on the decisions of such a “drunken bum?” In truth, Roosevelt was little different. By 1943-44 he was visibly dying, and his health was declared a state secret. Now, but not then, everyone knows that the most powerful man on earth, crippled by polio, had to drag himself across the floor of his office whenever he lost his balance and that he had to hide his crippled legs from public view for all his three terms in office. How could one trust such a crippled leader, preoccupied as he was with his own terrible illness?

Further, what do we make of Churchill’s obsession with the success of what he called his “soft underbelly of Europe strategy?” Later, the GIs involved in nearly two years fighting in Italy called it a “tough old gut.” Was this some subconscious wish to make up for his failure with the same strategy in World War I, when he launched the disastrous attack on the Dardanelles in 1915?

What about Roosevelt’s snap decision in 1942 to launch the first U.S. attack of the war in Europe on French North Africa? Instead of attacking the Japanese in the Pacific to avenge the day of infamy at Pearl Harbor, he completely surprised his generals when he announced that French North Africa would be America’s primary military objective. The French had been allies during World War I. Now, it was conceivable that these same French might soon be killing American boys. Was this sideshow against the French really a reflection of Roosevelt’s long-term dislike of the French and their Empire?

In short, can it not be said that great men, even sick or crazy ones, listen to their inner voices and not those of their advisers? They go their own way, regardless of the consequences. This may explain Hitler’s decision to launch the last great German counterattack of the war against the American forces in the Ardennes. All his generals were against his decision.

Even Dietrich of the SS thought the plan was crazy. He complained. How was he expected to push an armored force through the rugged, hilly Ardennes in winter snow with a limited supply of gasoline? As his chief of staff, General Fritz Kraemer, told Lt. Col. Joachim Peiper, who would lead the 6th SS Panzer Army’s attack, “Give me one tank on the River Meuse and I’ll be happy—just one tank!” Kraemer had little faith that the SS would ever reach Antwerp.

Germans Took 25,000 U.S. Prisoners in the First Week Alone

General Hasso von Manteuffel, who would lead the 5th Panzer Army in the coming battle, thought the same: the offensive could not succeed. He saw Hitler during the last conference before the great battle as “a stooped figure with a pale and puffy face, hunched in his chair, his hands trembling, his left arm subject to violent twitching which he did his best to conceal, a sick man apparently bowed down by his burden of responsibility.” In Manteuffel’s opinion, the best Hitler could hope for was a limited success, a pincer movement that would trap at the most 10 Allied divisions.

In the event, all of them were wrong. Whether sick, crazy, or deluded, Hitler’s attack shattered two American divisions within days. The Germans took 25,000 U.S. prisoners in the first week and were well on their way to the River Meuse, the last natural barrier between their armored spearheads and Brussels, the Belgian capital, and the great Allied supply port of Antwerp.

Despite his chronic illnesses, Hitler had correctly interpreted the Allied situation in the West as he had lain on his sick bed in East Prussia during those early days of September. He had realized that General Dwight D. Eisenhower’s broad front strategy, which entailed bringing up all the Allied armies to the German frontier before attacking, had meant the enemy forces were too thinly spread. According to the traditional German strategy of “klotzen und nicht kleckern” (mass not spread), any German army massing at one particular spot where the enemy was thinly spread, such as in the area defended by General Troy Middleton’s VIII Corps in the Eifel-Ardennes, would inevitably ensure a breakthrough. This it did in the Bulge.

Hitler had seen, too, that there was little real cooperation between the Anglo-American armies, especially when General Bernard Montgomery, the British commander, had proved such a thorn in Eisenhower’s side. A successful breakthrough at the seam between those two armies might well knock Britain out of the battle, especially since the British were scraping the barrel for manpower. Churchill purportedly was carefully husbanding his resources to protect the future interests of the British Empire and perceived Roosevelt as intent on doing away with it—something which Hitler had also believed.

What Hitler had not considered when he had started on Germany’s last great military adventure in the West were the imponderables. The foremost of these was the stubbornness of some of the American troops. The Führer thought the Americans would break and allow the whole front to be shattered as his Central European and Italian allies had done at Stalingrad. They did not.

Then, there was the weather. He had hoped for bad weather for the whole of the battle so that the Allies would not be able to use the massive superiority of their air forces. But, the weather obeys no one, not even military geniuses. It broke, giving clear blue skies in which Allied fighter bombers could fly and create havoc among the defenseless German troops below.

Failure at Ardennes

Finally, there was the inability of the attacking Germans, relying on a quick dash to the great Allied port of Antwerp in the style of the 1940 blitzkrieg, to find fuel necessary for the armor to complete such a lightning stroke. The tanks ran out of the “juice,” as the Germans called it. It was something else that Hitler apparently had not taken into consideration. If he had, he had not given it the importance it needed. However, military geniuses, mad or sane, mainly believe what they want to believe, blind to factors that do not fit into their plans.

In the final analysis, Hitler failed in the Ardennes. His armies did not reach their objectives. The Battle of the Bulge was a German defeat. In retrospect, however, one cannot truly say that it was an Allied victory. Not only did it postpone the end of the war for another two months and cost the valuable lives of many thousands of Allied servicemen, but it also enabled the Soviets to win a great political victory. Due to Allied entanglements and shortcomings in the West during the winter of 1944–45, the Red Army was allowed to penetrate deep into the heart of Central Europe.

Within months of the end of the war, General George S. Patton, Jr., was already telling one of Eisenhower’s deputies: “I really believe that we are going to fight them (the Soviets), and if this country does not do it now, it will be taking them on years later when the Russians are ready for it and we will have an awful time whipping them.”

The Cold War was on its way, and one might say that this 40-year struggle, which involved the Korean and Vietnam wars, was in a fashion, Hitler’s revenge. Crazy or not, the Führer had, that September, dreamed up a long-term scenario of death and destruction in that little wooden bed of his in that remote East Prussian forest.

Well-known author Charles Whiting wrote numerous books on topics related to World War II.

The article say that the Battle of the Bulge was an “Allied victory.” I am given to understand that battle was the only battle of World War II that pitted Americans against Germans.

Is this true?

This battle probably involved more Americans vs. Germans than most others, but I think it’s wrong to say it was only Americans. It was an Allied victory.

The author of this otherwise excellent article needs to be more precise with the WWII chronology. The article correctly states that North Africa was the first action in Europe, then goes on to say that was instead of attacking the Japanese in the Pacific – dead wrong. The landing is North Africa was in September 1942, long after we had attacked and, most historians agree, stopped the Japanese.

Let’s review.

December 1941, the Japanese attacked Hawaii and captured Wake island. April 1942 – James Doolittle’s raid, launched from US Navy carriers, bombed Tokyo, among other targets, seriously affecting Japanese morale. May 1942 – battle of the Coral Sea, a tactical draw, but a strategic victory, slowed the Japanese from their plans to invade Australia. June 1942 – Midway Island, the US Navy destroyed much of the Japanese Imperial Fleet and stopped any plans for further westward expansion. August 1942 – Guadalcanal, the six-month battle that put a complete stop to Japanese expansion south. From then on the Japanese were on the defensive. All before North Africa.