By Jon Diamond

Supreme Allied Commander General Dwight D. Eisenhower recalled, “The battlefield at Falaise was unquestionably one of the greatest killing fields of any of the war areas. Forty-eight hours after the closing of the gap, I was conducted through it on foot, to encounter scenes that could only be described by Dante. It was literally possible to walk for hundreds of yards at a time stepping on nothing but dead and decaying flesh.”

Royal Air Force liaison officer and Group Captain Desmond Scott similarly noted, “The roads were choked with wreckage and the swollen bodies of men and horses. Bits of uniform were plastered to shattered tanks and trucks and human remains hung in grotesque shapes on the blackened hedgerows…. Strangely enough, it was the shape of the horses that upset me most. Harnessed as they were, it had been impossible for them to escape, and they lay dead in tangled heaps, their large wide eyes crying out to me in anguish.”

Some of the enemy did manage to escape, but not unscathed. Lieutenant Walter Kruger, a signals officer retreating with the 12th SS Panzer Division, was struck by shrapnel as his truck slowly crept along the Falaise road, making it an inviting target for Allied artillery and fighter-bombers. “Then I saw that the whole column was on fire,” he said. “Everybody was running.”

This was the slaughter within the Falaise Pocket.

It began with the German Army’s thrust to the west toward Avranches in early August 1944 that surely ranks as one of the most ill-conceived military moves of all time. Many analysts agree that Hitler should have pulled his formations in France back toward the German border in an orderly fashion rather than shoving them forward toward Mortain to create a salient where they could be isolated, surrounded, and chopped to pieces—which is exactly what happened in the Falaise Pocket.

But, by the summer of 1944, Hitler’s previously astute military mind had deteriorated. The man who once considered himself a military genius–—on par with Napoleon and far superior to any of his generals or field marshals—now saw his armies crumbling in the east, in the west, and in the south.

How did the Allies, after almost nine weeks of desperate combat in the Normandy hedgerows or before the tenacious Nazi defenses at Caen, find themselves poised to inflict a devastating and final blow on the reeling German forces in Normandy, an attack that ended on August 21, 1944? And how was that “final blow” missed with so many Germans allowed to escape to fight another day?

Operation Cobra initiated the American breakout from the Norman hedgerows on July 25, resulting in the start of a fluid offensive with the capture of Avranches five days later. The British and Canadian forces of British Field Marshal Bernard L. Montgomery’s 21st Army Group eventually took Caen on July 9; however, the southern part of the city and the entrance to the Falaise plain were still under German control despite attacks by Montgomery’s forces throughout the entire month of July.

On August 1, Lt. Gen. George S. Patton’s Third Army became operational, was brought to France, and attacked through the Avranches gap into Brittany and southward toward the River Loire.

Two days later, on August 3, Hitler ordered Field Marshal Günther von Kluge, the Commander-in-Chief West (as well as Army Group B commander after Field Marshal Erwin Rommel was wounded on July 17 and sent back to Germany), to launch a counterattack against Patton’s army.

Kluge had a formidable force at his disposal, including the German Seventh Army commanded by SS-Obergruppenführer Paul Hausser, while the Fifth Panzer Army, with hundreds of tanks, was led by General Heinrich Eberbach.

Kluge planned to mount a heavy, single-pronged counterattack—Operation Lüttich—against Patton’s forces with at least four panzer divisions comprising SS-Obergruppenführer Willi Bittrich’s II SS Panzer Corps.

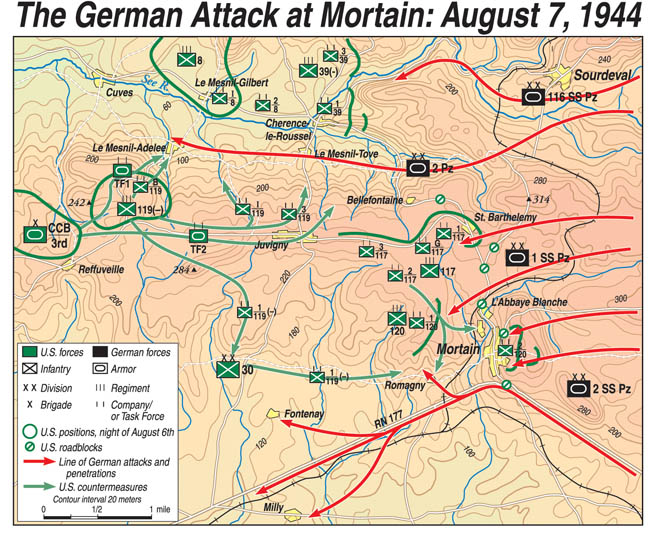

This counterattack began east of Mortain and drove westward toward Avranches in an attempt to envelop Patton’s forces and establish Avranches as the western flank anchor for a new continuous defensive line. Hitler conceived this attack as a springboard that would then thrust German armored forces northward into the rear of General Courtney Hodges’ U.S. First Army and, according to Hitler, “drive them into the sea.”

According to Hitler, “The decision in the Battle of France depends on the success of the Avranches attack. [Kluge] has a unique opportunity, which will never return, to drive into an extremely exposed enemy area and thereby to change the situation completely.” The Führer further reasoned that this offensive would cut off Patton’s Third Army from its logistical tail, allowing the Wehrmacht to crush the anticipated encircled forces to the south.

But, on August 5, Maj. Gen. Wade Haislip’s U.S. XV Corps, part of Patton’s Third Army, pushed through the gap at Avranches and turned southeast to Le Mans, where Hausser’s German Seventh Army headquarters was situated. The XV Corps was now in the rear of the German Seventh Army.

What became known as the Battle of the Falaise Pocket was a true example of the Allies fighting as a coalition. Apart from the initial landings at the five Normandy beaches on June 6, this final phase of the conflict in Normandy most closely brought American, British, Canadian, Polish, and Free French soldiers together in operational terms.

The Canadian First Army, commanded by Lt. Gen. Henry D.G. Crerar, would play a major role in the upcoming battle. Crerar had led the Canadian I Corps in Italy in the late winter of 1943-1944 before taking over as commander of the Canadian First Army.

Subordinate to him was Lt. Gen. Guy G. Simonds, commander of the Canadian II Corps, composed of the 2nd and 3rd Canadian Infantry Divisions, and the inexperienced Canadian 4th Armoured Division, commanded by Maj. Gen. George Kitching, along with the 2nd Canadian Armoured Brigade.

Additionally, Simonds would be in charge of two units on loan from British I Corps to reinforce the Canadians: the 51st (Highland) Infantry Division and the 33rd (British) Armoured Brigade.

Finally, Simonds would count within his corps the 1st Polish Armoured Division under Maj. Gen. Stanislaw Maczek. About 24,000 Polish soldiers reached Great Britain in mid-1940. They were soon reinforced by volunteers from Polish expatriate communities worldwide.

Maczek was an experienced soldier, having served during both World War I and the Polish-Soviet conflict of 1918-1920, but he had no experience in armored warfare when he took over the 1st Polish Armoured Division.

These foreign fighters were reorganized into the I Polish Corps and based in Scotland. Initially, the 1st Polish Armoured Division consisted of two armored brigades, each with six tank battalions comprising the 10th Motorized Cavalry Brigade and the 16th Armoured Brigade, along with a motorized infantry battalion taken from the Independent Highland Rifle Brigade. This unit, after reconnaissance and normal divisional administrative components were added, was ready for collective, inter-unit battle training in early 1943 in eastern England.

However, after readjusting its units’ composition to adhere to Britain’s new structure for armored divisions, the 1st Polish Armoured Division had only one armored brigade with an infantry brigade serving as its other major combat component with a total complement of 885 officers and about 15,000 other ranks.

This division was made up of the 10th Armoured Cavalry Brigade, the 1st, 2nd, and 24th Lancers Armoured Battalions, and the 10th Dragoons, a mechanized infantry battalion. The infantry brigade—the 3rd Rifle Brigade—in this division was comprised of the Highland (Podhalan) Rifles and the 8th and 9th Rifle Battalions. The 10th Mounted Rifle Battalion was to serve as the reconnaissance unit for the division.

The armored division possessed 350 tanks, 48 artillery howitzers, 48 medium and heavy antitank guns, and 54 medium antiaircraft guns. Although the division did not participate in the Normandy landings, elements of it began landing in France on July 30, eager to engage the Nazis after a four-year interval of migration, refitting, and training.

The Poles were eager to pay back the Germans for ravaging their country. Their wish would soon become reality during Operation Totalize. Simonds’ II Canadian Corps was about to launch from the eastern portion of the Normandy lodgement toward Falaise to the south against Kluge’s armored divisions.

On August 6, Montgomery pressed his 21st Army Group commanders in the field south of Caen to push for Falaise; the next day Operation Totalize was launched by Simonds’ II Corps after a heavy aerial bombing of German defenses south of Caen beginning at 11 pm on August 7.

Simonds’ 600 tanks advanced down both sides of the Caen-Falaise road toward Falaise, 15 miles away. The timing of the Canadian attack was accidental as it related to the Mortain counterattack. Coming 24 hours after the unexpected German westward attack toward Avranches, the Canadian effort, in preparation for almost a week, had been launched in an entirely different context, with Montgomery focusing on trapping the Germans west of the Seine River.

For Totalize, Simonds implemented some innovations in his tactical repertoire since previous British attacks, notably Operation Goodwood, down the Caen-Falaise road, had been stopped by heavy German antitank fire once British armored forces were in the open countryside. Simonds’ offensive would be launched at night and without a preparatory artillery barrage to conceal his movement.

It was Simonds’ expectation that tanks and mobile infantry would breach the initial German defense line, leaving the marching infantry to “mop up” any enemy pockets that were bypassed in the armored assault.

Finally, Simonds would employ RAF night bombers to lay a carpet of bombs along the battlefield’s flanks and front on the night of the attack, with American heavy and medium strategic bombers repeating the tactic in the breakout phase. From August 8-14, the U.S. IX Tactical Air Command flew over 4,000 sorties into the pocket, while their British counterparts flew 1,500. On several occasions the Allied fighter-bombers over the pocket were almost competing for airspace.

The aerial assault of more than 1,000 RAF Bomber Command aircraft targeted the area between May-sur-Orne and Fontenay-le-Marmion on the right, or western, flank and La Hogue and Mare de Magne to the left, or eastern, flank.

Facing Simonds’ attack was the German 89th Infantry Division, which was shattered by the aerial bombardment. The 51st (Highland) Division, supported by the 33rd (British) Armoured Brigade, took La Hogue, Tilly La Campagne, and Secqueville la Campagne on the left flank. On the right flank, the French villages had likewise been taken by midday on August 8 with II Canadian Corps’ new tactics.

However, on that day an American Eighth Air Force bomber attack accidentally hit Canadian, British, and Polish troops, causing more than 300 casualties.

As the Allies began to move forward again, German Tiger tanks and 88mm antitank/antiaircraft guns of Standartenführer Kurt Meyer’s 12th SS Panzer Division “Hitler Jugend” took their toll on Allied armor.

Terrific tank-versus-tank battles occurred on August 8, but Simonds’ II Corps had reached a standstill and could not penetrate German defenses farther in its southward advance toward Falaise. The Polish 2nd Armoured Battalion of the 10th Armoured Cavalry Brigade lost about two-thirds of its M-4 Sherman tanks during the German attack.

The 24th Polish Lancers Armoured Battalion also incurred heavy tank losses to German artillery and Tiger tank fire. By the end of the day, the Canadians and Poles had created about a six-mile salient but had been stopped by German firepower more than 12 miles north of Falaise.

During the night of August 8-9, elements of SS Oberstgruppenführer Joseph “Sepp” Dietrich’s I SS Panzer Corps, along with some survivors from the previously bombed German 89th Infantry Division, reinforced a partially built new defensive line to the east of the Caen-Falaise road. Other infantry units from the German 85th Division also started to arrive from the German Fifteenth Army.

During the early hours of August 9, the Canadians and Poles again commenced a nighttime assault, but it failed when Canadian armor and infantry from the 28th Armoured and Algonquin Regiments, respectively, got in the Poles’ way and arrived at Point 140, the Polish objective.

As a result of Canadian forces being in accidental proximity to a new German line under construction, Meyer unleashed his 12th SS Panzer Division “Hitler Jugend” and assorted units of SS and Wehrmacht infantry, which forced the Canadians to withdraw after losing about 50 tanks and suffering more than 200 casualties.

Although Meyer’s panzer force was severely depleted of armored vehicles after the fighting at Caen, it was still capable of fielding more than 100 88mm and 75mm antitank guns, which halted the renewed Canadian advance at dawn on August 9 and stopped the Polish armor from advancing into the villages in the vicinity of the new German line. Meyer’s tanks and antitank guns were effective at countering every Canadian armored thrust that day.

Simonds’ approximately 600 tanks at the start of Operation Totalize, among his two untested armored divisions, had failed to breach this new German defensive line, which had only 35 panzers of all types by August 10.

Simonds halted Totalize and defended his gains with his infantry divisions, while the Canadian, British, and Polish armor was pulled back to await new orders.

Simonds believed that a lack of drive and the inexperience of his two armored divisions were the most decisive factors in explaining the operation’s failure. Despite the tenacity of the Germans in their defensive posture, Totalize did, however, maul the Wehrmacht and SS formations, leaving their positions critically weakened.

When Operation Totalize ended on August 11, the II Canadian Corps had advanced almost nine miles toward its objective of Falaise but was still bogged down several miles north of the town in the Caen-Falaise corridor.

On the 11th, Montgomery issued a new directive to close the narrowing gap that the Germans were attempting to exploit in the area between Falaise and Argentan. He ordered Crerar to move his First Canadian Army south and link up with the advancing Americans to ensnare as many Germans as possible. This became Operation Tractable.

For Tractable, during which Simonds was to make his thrust down the N158—the Caen-Falaise road—a series of feints were conducted to the west of the road on August 12 and 13; however, these failed when the plans for the movements were discovered by the Germans on the body of a dead Canadian officer.

On the night of August 12-13, Falaise was heavily bombed by Allied planes and completely flattened. The next day Montgomery was still optimistic that Crerar’s forces could move swiftly through Falaise to Argentan. The cause for Montgomery’s optimism was somewhat specious since he believed that Crerar’s army had performed poorly; however, no attempts were made to alter the plan or the Anglo-Canadian-Polish forces involved.

Nonetheless, Montgomery stated, “If we can close the gap completely … we shall have put the enemy in the most awkward predicament.” Thus, the prospect of a quicker encirclement in the Falaise-Argentan area caused the Allies to suspend Montgomery’s drive for the Seine. However, Monty still held out the possibility of a wider encirclement of German forces toward the Seine should the Germans continue to attempt to escape eastward.

Kluge’s Operation Lüttich, which had begun on August 7, made some significant initial gains against Maj. Gen. J. Lawton Collins’ VII Corps on the U.S. First Army front. Mortain was overrun, but the German offensive was halted later on its first day by stiff American resistance from Maj. Gen. Leland S. Hobbs’ 30th Infantry Division, defending the important height of Hill 317 to the south of Mortain, and by tactical air support.

Further German attacks over the next few days failed to give Hitler his desired breakthrough. Hitler intensified this flawed westward movement when he dismissed Kluge’s plea for an orderly eastward withdrawal and ordered Eberbach to take command of an ad hoc formation, Panzer Group Eberbach, with the Führer’s order to drive to the southwest and then to move northwestward to the sea. Fifth Panzer Army would be turned over to Dietrich.

Eventually, the panzer forces were driven back. With the failure of Operation Lüttich to capture Avranches, Lt. Gen. Omar N. Bradley, commander of the U.S. 12th Army Group, saw that Hitler had exposed his whole broad flank to attack and encirclement from the south and recognized this as an opportunity to decimate a large percentage of the German Seventh Army and Fifth Panzer Army in Normandy.

Bradley, concluding that Kluge had committed strategic suicide, said, “This is an opportunity that comes to a commander not more than once in a century. We’re about to destroy an entire hostile army and go all the way from here to the German border.”

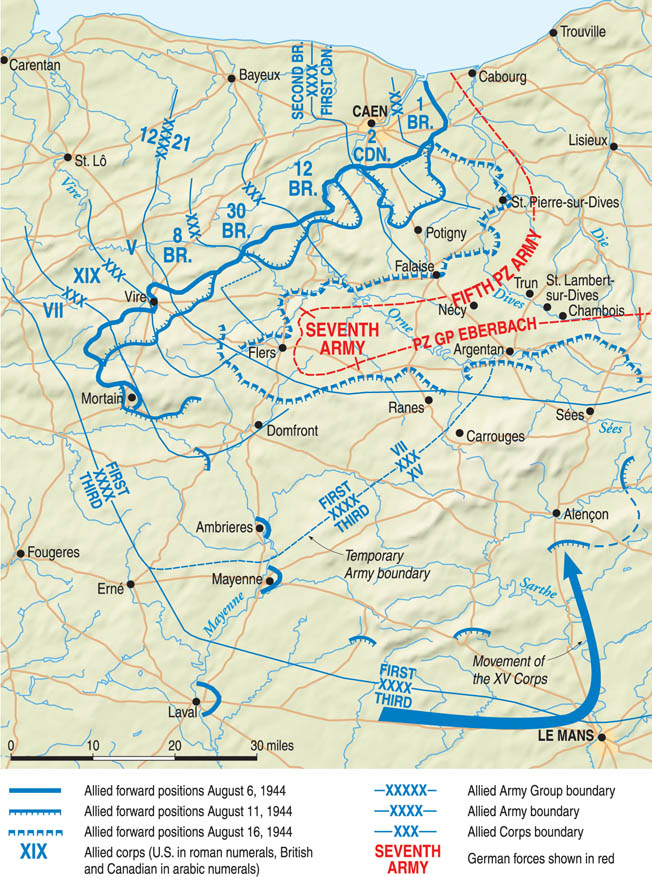

On maps it appeared that the Germans were trying to head eastward through the 13-mile gap between Falaise and Argentan. If XV Corps now moved northward from Le Mans through Alençon, Bradley saw, the German Seventh and Fifth Panzer Armies would be trapped as long as Crerar’s First Canadian First Army could continue its southward movement into Falaise first, and then Argentan, thereby forming the northern jaw of the pincer strategy.

Concurrent with this move, American forces not committed to the clearing of Brittany would move northward toward Falaise, thus completing the envelopment of the Germans. As Bradley concentrated American forces near Mortain to maintain possession of Avranches, he conceived an envelopment that would trap the bulk of Kluge’s armies in eastern Normandy.

On August 8, Bradley discussed with Eisenhower the opportunity offered by the Germans’ Mortain counterattack. Bradley was in favor of implementing the simpler tactic of turning Haislip’s XV Corps north from Le Mans. Instead of heading eastward for the Seine to start the larger envelopment that Montgomery favored, Bradley wanted a “shallower and surer movement” aimed at the exposed German flank that had moved east to attack Mortain.

With this shorter envelopment, once the Canadians reached Falaise and then continued southeast to Argentan the meeting of the Allies would cut off the escape route of an estimated 21 German divisions. Bradley, in Eisenhower’s presence, notified Montgomery to secure his approval for a change in plan.

Bradley proposed that XV Corps pivot north from Le Mans toward Alençon, where U.S. infantry and armor would threaten the flank of Kluge’s counterattacking forces and also form the southern jaw of the proposed pincer movement and finish off the majority of the German Army in France. It was an audacious, heady possibility, and Monty agreed.

Haislip’s XV Corps—composed of the U.S. 5th Armored Division, the 79th and 90th Infantry Divisions, and Maj. Gen. Jacques Leclerc’s French 2nd Armored Division—took Le Mans on August 9 and the following day jumped off to the north to begin the pincer movement against the Germans. The area within which Kluge’s German forces would be encircled would be known as the Falaise Pocket.

Opposing Haislip’s move against Alençon were elements of two German divisions, the 708th Infantry and 9th Panzer. However, one of 9th Panzer’s Panther tank battalions had temporarily been sent to support the defense of Falaise and the 708th Infantry Division was not at full strength, having been previously mauled by the U.S. 90th Infantry Division.

Due to the fluidity of the battlefield as a result of the Germans’ failed Mortain counterattack, Montgomery analyzed on August 11 the consequences of the anticipated juncture of the American and Canadian-Polish forces. He came to the conclusion that Kluge would mass stronger German forces to defend Alençon rather than Falaise.

Extending this line of reasoning, Montgomery believed that Simonds’ Canadian II Corps would make speedier progress and reach Argentan from the north before XV Corps could arrive from the south. Montgomery therefore ordered Simonds to continue his efforts to take Falaise and then head for Argentan.

Montgomery had drawn a boundary line that separated the zones of operation of Bradley’s American 12th Army Group and his own 21st Army Group. This meant that XV Corps was to advance through Alençon and go no farther north than the army group boundary just south of Argentan.

Historian Martin Blumenson said, “[Montgomery] projected a meeting of Canadian and American forces just south of Argentan, which would form a literal encirclement of the Germans. The British Second Army and the First U.S. Army, pressing from the west, were to herd the Germans into the Canadian-American line and assist in the total destruction of the surrounded enemy forces. Should the Germans somehow evade encirclement at Argentan, Montgomery was ready with an alternate plan: the Allies were to reinstate the drive earlier projected to the Seine.”

Therefore, as of August 11, Montgomery’s strategic thinking had also involved a larger, more westward envelopment at the River Seine.

By nightfall on August 11, Hitler had approved Kluge’s request to make a minor withdrawal from Mortain to defend Alençon. But Haislip had already reached Alençon and there had clashed with the 9th Panzer Division. Allied planes and tanks had reduced that division to a battalion of infantry, a battalion of artillery, and only a dozen tanks.

The XV Corps captured Argentan on August 12, after overcoming both German infantry and panzer opposition, and Haislip reported to Patton that he had taken Argentan with his two armored and two infantry divisions and was ready to move north to meet the Canadians; Patton, disregarding the boundary line, told him to push on “slowly” in the direction of Falaise. The American and French forces were now just over 12 miles south of Argentan, while the Canadians, Poles, and British troops were about 22 miles north of it.

Seeing no Canadians in the vicinity, Haislip asked Patton for authority to proceed north across the army boundary line in Argentan. Since the Canadians had made little progress toward Falaise due to strong enemy opposition, Patton allowed Haislip to “push on slowly in the direction of Falaise.”

An almost 35-mile-wide corridor still existed for Kluge’s armies to escape through, but instead of rushing to seal off this corridor both Bradley and Montgomery made decisions that would baffle historians.

As XV Corps patrols slowly reconnoitered north of Argentan on August 13, Haislip notified Patton that he believed he could hold the southern shoulder of the pincer between Alençon and Argentan—less than 15 miles south of Falaise.

Seeing a gap that desperately needed to be closed, Patton asked Bradley’s permission to allow Haislip to continue northward, but Bradley refused Patton’s request when the latter flippantly inquired, “Should he [Haislip] now continue and drive the British into the sea for another Dunkirk?”

On August 13, Bradley, with Eisenhower’s approval, gave Patton a stop order: Third Army was not to move north of Argentan on the basis of previously arranged army boundaries. This left the Germans, although overextended and vulnerable to entrapment, with only the escape route to the east still open.

Bradley then received word that Patton had disregarded his instructions and had sent Haislip’s patrols on past the stop line at Argentan; the patrols had gone eight miles north of Argentan to within six miles of Falaise.

Angrily, Bradley not only reiterated his stop order to prevent any movement north of the line, but many sources claim that he also recalled Haislip’s reconnoitering forces to Argentan.

A near apoplectic Patton could not believe the rationale for the stop order, namely, Bradley’s stressing the “need to avoid collision between Americans and Canadians … potentially prompting accidental gunfire against each other.”

Newer boundary lines could have been drawn before any friendly gunfire was exchanged between the Allied units. Additionally, Bradley informed Patton that he was also reluctant to move north of Argentan since he wanted the Third Army forces to reinforce the southern shoulder because he believed that Kluge’s German divisions were in the process of pulling out of their Mortain salient.

Finally, in regard to the stop order, Patton insisted that Bradley’s headquarters staff (in Bradley’s absence) contact Montgomery’s chief of staff, Freddy Guingand, requesting permission from the field marshal, the Allied Land Forces commander, for Patton to push north. Answering for Montgomery, de Guingand gave a negative reply.

The rationale for why Bradley did not allow Patton to let XV Corps continue north and seal the Falaise-Argentan pocket has been debated ever since. The decision lost what most historians now agree was the best opportunity to encircle the German forces in Normandy and to achieve their complete destruction.

Kluge recognized his dire predicament and abandoned any further assault toward Avranches, to which Hitler reluctantly agreed. But Kluge could withdraw to the east on only one major road, and his fear was that a closure of the gap between Argentan and Falaise would leave his eastward-bound armies trapped.

During the afternoon of August 13, Haislip began to meet increasing German resistance just beyond Argentan as the Wehrmacht’s 116th Panzer Division and elements of the 1st and 2nd SS Panzer Divisions from Panzer Group Eberbach blocked XV Corps’ reconnoitering.

Some have argued that Bradley’s halt order to Patton may have saved Haislip’s XV Corps from being attacked on its flank by these German panzer forces if the Americans had continued to advance well beyond Argentan. A gap of between 25 and 50 miles existed between the First Army on XV Corps’ left, as the former was just starting to come up from Mayenne.

To the east of XV Corps, an armored cavalry battalion screened its even more open right flank. This could not have been a reassuring tactical development for Bradley, who seems to have been “more concerned with security than with encirclement.” Bradley stated after the war that he “much preferred a solid shoulder at Argentan than a broken neck at Falaise.”

Bradley was content with the notion that the continued presence of the Falaise-Argentan gap would be an invitation for Kluge’s forces to escape through this corridor, where they would be vulnerable to Allied artillery and tank gunfire as well as seemingly never-ending assaults by American and British air power.

Truth be told, Operation Tractable was but a replay of Totalize with some minor modifications. Beginning just before noon on Monday, August 14, rather than at night, Simonds’ relatively new tactics of heavy aerial bombardment and armored infantry carriers were employed again, under a smokescreen as cover, utilizing the Canadian 4th Armoured Division, the Canadian 3rd Infantry Division, and the Canadian 2nd Armoured Brigade.

Their goal, after crossing the River Laison, was to reach Hill 159 to the north of Falaise. The Poles would make a slight flanking move and attack alongside the Canadian 4th Armoured Division.

The German defense was especially tenacious, with Hill 159 not being taken by the Canadian 3rd Infantry Division until August 16. Concurrently, the Canadian 2nd Infantry Division, which was tasked with the capture of Falaise, only reached the outskirts of the town on that day. It would require an additional 48 hours of hard fighting to evict Meyer’s 12th SS Panzer Division with its panzergrenadier units using every bit of rubble as makeshift defensive positions.

Despite a good start to Tractable, the usual heavy German fire emanating from the wooded high ground beyond the Laison caused many casualties among the Canadians, both tankers and infantry. The associated Allied heavy bomber support once again caused hundreds of friendly fire casualties.

On August 15, Kluge disappeared for a day after his staff convoy was hit by Allied fighter-bombers en route to German Seventh Army commander Hausser’s headquarters; he had spent the day hiding in a ditch. After Kluge rejoined his C-in-C West headquarters, he finally received the long-awaited permission to withdraw his troops from the westward salient through the gap eastward to a new line along the River Dives.

Kluge was instructed to return to Berlin. He reasoned that Hitler might have suspected some treachery involved with his absence from his headquarters (Hitler suspected that Kluge was trying to make a “deal” with the Allies) along with some innuendo about his remote involvement with the July 20 assassination attempt on the Führer.

So Kluge, fearing merciless punishment by the Gestapo, committed suicide while returning to the German capital. Field Marshal Walther Model, one of Hitler’s most reliable generals from the Eastern Front, became the new C-in-C West.

On the evening of August 15, the Polish 10th Mounted Rifles, together with a company of motorized infantry from the 10th Dragoons (Motor) Regiment of the 1st Polish Armored Division, made it across the River Dives east of Falaise. The result of the frenetic Canadian II Corps’ attack during Tractable was to place two Allied armored divisions across the Dives.

In an attempt to obey Bradley’s order to not move farther north of Argentan, especially with increasing German resistance in that direction by Panzer Group Eberbach, Patton allowed a part of Haislip’s XV Corps—the 5th Armored and 79th Infantry Divisions—to maneuver east toward the Seine on August 15, leaving the 2nd French Armored Division and the U.S. 90th Infantry Division to form the southern shoulder of the pocket. Haislip’s two divisions reached the Seine 48 hours later.

On August 16, the Canadian 4th Armoured Division joined the 1st Polish Armoured Division crossing the River Dives far to the east of the Falaise-Argentan road with both Trun and Mount Ormel lying on a southeastern tangent from Falaise. Trun, with its important road junction, was just over four miles northwest of another important French village: Chambois. The gains of the Canadians and Poles were hard won against elements of the German 272nd and 85th Infantry Divisions.

Bradley was persuaded by Patton on August 14-15 to expand Third Army’s eastward movement to the Seine with the other divisions of XX Corps, as well as those of XII Corps. This decision, together with Bradley’s earlier order to halt XV Corps’ northward advance, continued to deprive the Allied coalition of the opportunity to seal the Falaise-Argentan gap sooner and achieve a more comprehensive victory. In essence, Bradley had effectively abandoned his shorter envelopment for a wider one when his earlier plan was on the verge of success on August 13-14.

An ad hoc corps of Patton’s American and French forces that remained at Argentan would be joined by the U.S. 80th Infantry Division from XX Corps and be provisionally placed under the command of Maj. Gen. Leonard Gerow for a continued northward move from Argentan to link up with Simonds’ II Canadian Corps.

This formation would be battling Panzer Group Eberbach, which had moved southward on August 13 for Hitler’s proposed “drive to the sea” to face the American and French forces at Argentan.

Given the reduction in combat power caused by the departure of two divisions of XV Corps and most of their artillery, there seemed to be little chance of closing the Falaise-Argentan gap from the American side. On the suggestion of Montgomery, Bradley, on August 16, relaunched efforts to shut off the pocket from his Argentan sector with forces that had been greatly reduced in strength. The objective of the American attack would now be a meeting point between the Allied armies in the town of Trun.

The U.S. 90th Infantry Division was tasked with the capture of Chambois and cross the River Dives, which ran through the town. Elements of the 2nd French Armored Division were then to pass through the 90th Infantry Division and drive on Trun, less than five miles northwest of Chambois.

As the German Seventh Army was now methodically moving eastward, with Panzer Group Eberbach defending the southern shoulder of the front near Argentan, Allied fighters, fighter-bombers, and medium bombers continually sortied with devastating attacks on the long lines of enemy vehicles and troops since the Wehrmacht forces now had to move during daylight to get to the River Dives in a timely fashion.

On August 17, the German commanders had observed that the Canadian attack east of Falaise had slackened somewhat, and Panzer Group Eberbach was holding off the Americans on the southern shoulder of the pocket. Hausser and Eberbach were planning that their units would cross the Dives over the next two to three nights.

As a result of reassessing the slow progress of the Canadian offensive, it was apparent to the Allied commanders, most notably Montgomery, that Simonds’ forces would not reach Argentan in time to seal the eastern end of the pocket.

The other problem for the Allies was that the Canadians were still more than 15 miles from Chambois on August 16; Montgomery urged Crerar and Simonds to move the Canadian 4th and Polish 1st Armoured Divisions to Trun and then Chambois on the River Dives to close the eastern end of the pocket.

At 2:45 pm on August 17, Montgomery issued a new directive for II Canadian Corps to close the remaining gap through which the German forces were escaping by having the 1st Polish Armoured Division go “past Trun to Chambois at all costs, and as quickly as possible.” The closing of the gap by both Allied forces was now shifted to Chambois and Trun, both northeast of Argentan on the River Dives.

Despite some pockets of resistance manned by elements of the 2nd SS Panzer Division “Das Reich” that the Poles had to overcome on August 17 and 18, by the evening of the 18th two Polish battle groups were on the northeastern outskirts of Trun, a short distance from Montgomery’s and Bradley’s new objective of Chambois.

Although Falaise was still a Canadian objective, its significance in the development of the encirclement was diminished as Allied forces shifted eastward. Still, the Canadians had attacked Falaise on August 16, and the last pockets of German resistance there were extinguished by August 18.

At 7:30 am on Thursday, August 17, Maj. Gen. George Kitching launched elements of his 4th Canadian Armoured Division, which was massed northeast of Falaise, southeastward toward Trun. At nightfall, armored units were a short distance from Trun; the following day motorized infantry took the town without much difficulty.

With the seizure of Trun, II Canadian Corps was finally closer to sealing off the remaining space between the Allied forces. But a narrow passageway still remained between Trun and Chambois on August 18 for the Germans to withdraw north and east to safety. This four-mile passageway soon would become known as “the corridor of death.”

On that day, the German escape route from the ever shrinking Falaise Pocket was further narrowed to the area between Trun and Chambois along the River Dives. Complicating matters for the retreating Germans was not only the Canadian capture of Trun but also the 1st Polish Armoured Division’s capture of the heights of Mount Ormel, a hill two miles east of Chambois that overlooked the German escape route through the Dives River Valley.

Elements of the 1st Polish Armoured Division collided with the II SS Panzer Corps as the latter was heading eastward toward Trun with specific instructions to keep the escape route open. To prevent getting bogged down in an armored slugfest with the German panzers, the Poles moved east of their intended track and swung south over Mount Ormel to get to Chambois.

However, the Polish armor was cutting across the German escape route, and almost continuous combat occurred. General Maczek established his divisional headquarters on Mount Ormel on August 18 in an attempt to close the pocket and bag the two Nazi armies.

Also on the 18th, elements of Kitching’s Canadian 4th Armoured Division were moving from Trun down the Dives Valley to join the Poles heading for Chambois. The next day, after Maczek put together an ad hoc formation, elements of his 1st Polish Armoured Division linked up with the American 90th Infantry Division, advancing from the south, in Chambois but lacked sufficient troop strength to seal the pocket completely. A combat command of the French 2nd Armored Division also tried unsuccessfully to cut the road to the east.

Desperate fighting ensued. Trun and Chambois were now the shoulders of the narrowing German escape route to the east, which the II SS Panzer Corps was desperately trying to keep open.

On August 19, the Canadians and Poles combined to attempt to seal the new gap. The loss of Chambois to the Allies and the presence of Canadians along the Trun-Chambois road meant that those German troops remaining in the pocket would have to fight their way out as fragmented combat commands and battle groups led by junior officers and NCOs.

The two main escape routes for thousands of Germans were now a foot bridge over the Dives River at St. Lambert, halfway between Trun and Chambois, and a ford at Moissy. The roads exiting the Dives Valley from St. Lambert and the Moissy ford led up to Mount Ormel, which was now in the hands of Maczek’s 1st Polish Armoured Division.

On the night of August 19-20, the Germans, still trapped within the pocket, again battled to break out to the east but their way was blocked by the Poles atop Mount Ormel, and some of the fiercest fighting of the war took place. Hundreds of Germans died trying to get around the hill, but Polish gunners had them well sighted in the open country below the heights and showed no mercy.

The ground was carpeted with dead soldiers and horses. By morning, the remnants of the German II SS Panzer Corps, trying to keep the pocket open, launched another heavy counterattack, but the Poles held onto their encircled positions atop Mount Ormel, with much-needed ammunition resupply being furnished by air.

By late afternoon on August 20, the II SS Panzer Corps’ attack sputtered out. The Poles remained in possession of Mount Ormel.

On August 20-21, remnants of the German Seventh and Fifth Panzer Armies made last attempts to cross the Dives before the pocket was entirely sealed, while the Canadian 4th Armoured Division fought its way through to relieve Maczek’s isolated division atop Mount Ormel.

Germans were clawing at each other in desperate attempts to cross the Dives at a bottleneck—the small ford at Moissy. Kurt Meyer, commander of the 12th SS Panzer Division, survived to write, “There was a continual bombardment registering bulls-eyes every time. The Canadian and Polish guns found our range and could not miss. The whole country was saturated with dead or wounded German soldiers.”

After additional Canadian and American reinforcements pushed along the Dives River Valley on August 21 to meet the Poles in Chambois, the Falaise Pocket was finally slammed shut, ending any further chance for the entrapped German forces to escape eastward. Artillery and aircraft pummeled those who remained.

It is estimated that 10,000 Wehrmacht soldiers died in the August 6-21 battle with another 50,000 taken prisoner. This was in addition to about 350 armored vehicles, 2,500 trucks and cars, and 250 towed artillery pieces destroyed or abandoned. Yet, the number of Germans who escaped might have been as great as 40,000.

The slaughter was horrendous; soldiers of every rank were sickened by the sights and smells within the Falaise Pocket. One American officer said, “I stood on a lane, surrounded by 20 or 30 dead horses, most of them still hitched to their wagons and carts.” A Canadian captain recalled, “A German truck had been hit by a shell in the driver’s seat; the man’s feet were still on the accelerator but the rest of the body had been blown 20 feet in the air into a tree.”

A war correspondent noted, “A convoy of vehicles had been surprised by [RAF] Typhoons. You could walk along them for 330 yards. Each vehicle was a hulk and the crews were rotting corpses on the verges. This is the type of thing you do not try to describe, but to forget.” Even pilots reported being able to smell the stench of the battlefield hundreds of feet above it.

Many questions still surround Falaise. From a leadership standpoint, why did Montgomery, who was commander of all the Allied ground forces in France, not close the pincer from the south with the American and French forces at Argentan on August 13, 1944? Why did Bradley, with the Canadian-Polish forces struggling to make gains in their offensive toward Falaise during Operation Totalize, stop Patton’s forces from extending past Argentan on August 13? Why did Eisenhower remain in the background of his 12th and 21st Army Group commanders’ decision making?

These are just some of the questions that historians have debated for seven decades. Montgomery was known for being cautious, and Blumenson described Bradley as one who “preferred to take no chances.” Many have realized that Eisenhower was a better “political general” than a strategic or tactical one. The “perfect storm” in not closing the gap was present in these generals’ personalities. This was in sharp contrast to Patton, who espoused, “A good plan violently executed now is better that a perfect plan next week.”

Montgomery had another pragmatic constraint to deal with. He was reluctant to incur heavy casualties, especially among his British forces, since he had received logistical information from Brooke and Churchill that the United Kingdom was running out of able-bodied men to serve in the military and that this was becoming a political strain as well as a military one. In fact, during the summer of 1944, Montgomery was informed that he could be supplied with British troops only for about two more weeks of fighting.

Strategically, Montgomery was also seemingly preoccupied with the much larger envelopment extending to the Seine rather than Bradley’s initial inner one involving the closure of the Falaise-Argentan pocket. On August 4, Montgomery had issued a full-scale directive formally setting the course of action for the Allies as the normal next step after the hedgerow breakout following Operation Cobra on July 25.

Identifying the breakout as the disintegration of the enemy, Montgomery envisioned that the Germans’ next step would be to pull back to the Seine. This would enable the Allies to seize the area west of the Seine. Based on intelligence reports, Montgomery’s plans would take advantage of the lack of bridges over the Seine by pinning the remaining German armies west of the river.

On the evening of August 13, Patton noted in his diary that he “could easily advance to Falaise and close the gap,” thereby completing the encirclement of the Germans. In another diary entry on August 16, Patton speculated that the stop order had come from Montgomery’s command due to “jealousy of the Americans or to the utter ignorance of the situation or to a combination of the two.”

While Patton awaited the arrival of the Canadians and Poles from the north, he watched as the Germans built up the shoulders of the gap as German troops and equipment escaped east. On August 17, a fighter pilot during a sortie noted that the escape corridor within the Falaise pocket remained open and “the whole goddam German Army was moving through the gap.”

There are other explanations for the delay in closing the Falaise-Argentan pocket. Bradley had identified that Falaise “was a long-sought British objective and, for them a matter of immense prestige. If Patton’s patrols grabbed Falaise, it would be an arrogant slap in the face [to the British] at a time when we clearly needed to build confidence in the Canadian Army.”

In his memoirs, Bradley recounts that by August 13, he, Eisenhower, and Montgomery had received extensive intelligence briefings “which conveyed that the enemy was escaping and that many had already escaped.”

Bradley described the news as a “shattering disappointment … one of my greatest of the war. A golden opportunity had truly been lost. I boiled inside, blaming Monty for the blunder. We had done our part, set the lower jaws at Argentan and restrained Patton from a brash and foolish overextension.

“Monty, perhaps, too busy with his strategic plans, had turned his part over to the Canadians, an unproven army depending to a great extent on two armored divisions, one Canadian and one Polish, both new to combat.”

Bradley also stated after the war, “In halting Patton at Argentan, however, I did not consult with Montgomery. The decision to stop Patton was mine alone.” One has to ask why Bradley did not communicate the halt order to Montgomery himself.

Thus, the failure to close the Falaise-Argentan gap could be considered a symptom of a dysfunctional chain of command—perhaps, reducing Montgomery’s role as Allied land forces commander in France or at least preventing an Allied coalition ground assault on the same objective. In the end, despite knowing about Britain’s ebbing manpower, Montgomery should have admitted that his forces could not complete their mission on time and allowed the Americans to close the pocket.

The failure of the Allies to close the Falaise-Argentan pocket, thus, was two-fold. First, Bradley’s decision late on August 13 stopping Haislip’s reconnaissance forces from moving north of Argentan; that was a major reason why so many Germans escaped entrapment and destruction. Second, the failure of the Allies to close the pocket was the result of a lack of adequate communication directly linked to the personalities of the commanders. Despite a unified command structure, each part of the coalition gave every appearance of fighting its own battle; Bradley gave the impression of ambivalence in his interactions with Montgomery.

As for Monty, he knew that his time for directing all the Allied armies was limited, with Eisenhower about to assume overall command of Allied land forces in a matter of weeks. Montgomery, too, knew that with the growing American military strength he could only attempt to persuade and coordinate how the U.S. Army commanders conducted their tactical movements rather than issue detailed orders directly. Such was the nature of coalition warfare in France during the battle for Normandy and later northwestern Europe.

Unfortunately for the Allies, it allowed thousands of enemy troops to slip away to fight another day.

no comment