By Victor J. Kamenir

In the English-speaking world, most students of military history would be hard-pressed to identify the time, place, or antagonists of the Canakkale Campaign. However, they would readily recognize it by its English name—Gallipoli. The Allied troops who went ashore at Gallipoli believed they were fighting for democracy. Few Westerners realized (or at any rate admitted) that their Turkish opponents were fighting for an even higher ideal—they were defending their country. A significant portion of the Turkish soldiers who fought in the Canakkale Campaign were recruited from the towns and villages of the Gallipoli Peninsula. With their families close behind the battle lines, these soldiers were literally fighting for their homes. To them, the Allied soldiers were invaders who had come to defile their country and their Muslim faith.

Deutschland uber Allah: the Ottomans Enter the War

In 1915, World War I was in its second year. On the Western Front, the inexorable meat grinder of trench warfare had replaced the early war of maneuver. Stalemated British, French, and German armies stared at each other across the scarred Belgian and French countryside. Meanwhile, on the Eastern Front, where operations of Austro-German and Russian armies still maintained some measure of fluidity, things were beginning to bog down there as well. The eyes of both sides turned south, toward the Ottoman Empire. With the Turks firmly in command of both the Dardanelles and Bosporus Straits, a vital supply route between Russia and Western Europe had been cut. Russia needed weapons and munitions from England and France. In turn, those two countries needed Russian food shipments. To England and France, Turkey seemed like the soft underbelly through which a serious blow could be delivered at Germany. The Germans, for their part, were looking for a place to divert British and French efforts and relieve some of the pressure on the Fatherland.

For more than a decade, the German and Ottoman empires had maintained close ties, especially in the military sphere. Shortly before the start of the war, a German military mission of almost 100 officers arrived in Turkey, invited there to overhaul the creaking Ottoman war machine. One of the most senior members of this mission was General Otto Liman von Sanders, who was destined to play a key role in the Gallipoli campaign. When the war started, Turkey initially maintained its neutrality. Then, in an act of either calculated effrontery or callous arrogance, England withheld two battleships it had been building for Turkey. The Turks’ indignation was understandable, since they had already paid for the battleships. Not only was England keeping the vessels, it also refused to return its client’s money.

German warships soon entered the picture. On August 10, 1914, hotly pursued by combined British and French squadrons, two German vessels, Goeben and Breslau, took refuge in Turkish territorial waters. In a sham sale, Turkey acquired the ships from Germany. Re-flagged under Ottoman colors and bearing the new names Midilli and Yavuz, the two ships were still manned by their German crews, who went through the ridiculous charade of wearing fezzes and pretending to be Turks. A rueful pun made the rounds: “Deutschland uber Allah.”

Turkey decided to enter the conflict on the German side. On October 27, the two newly acquired warships sailed into the Black Sea, bombarded several Russian cities on the north shore of the sea, and sank two merchant vessels. Although damage was minimal, Russia immediately declared war on Turkey. Great Britain and France quickly followed suit, and on November 3 combined British and French squadrons bombarded Turkish military installations near the entrance to the Dardanelles Straits, heavily damaging two small forts. Turkey, in turn, formally declared war on England and France. Another country had been drawn into the European bloodbath.

Dardanelles Strait: Istambul’s Gate

The Ottoman Empire was separated into the European portion and the Asian portion by the narrow Sea of Marmara. The Dardanelles Straits formed the gates to that British lake, the Mediterranean Sea, while the Bosporus Straits guarded the entrance to the Black Sea, dominated by Russia. The Gallipoli Peninsula (anglicized name of the small town of Gelibolu on the European side of the Dardanelles) gave its name to the upcoming campaign in the English-speaking world. The Turks named the campaign after the town of Canakkale, on the Asian side of the straits.

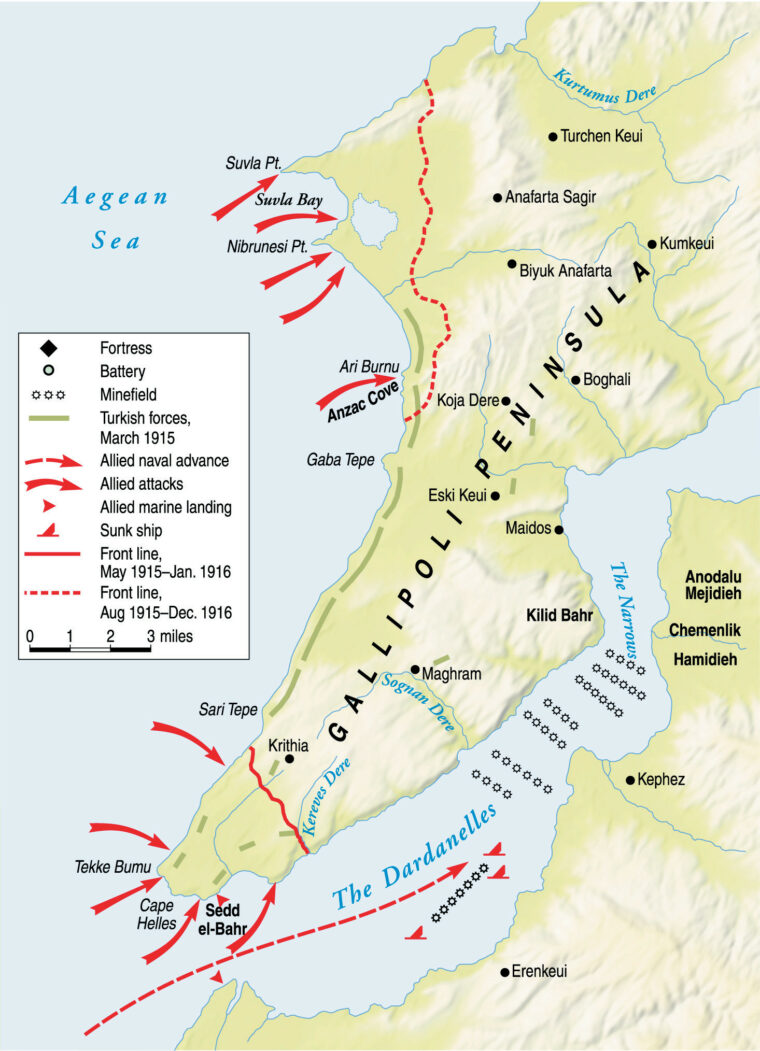

Hoping for a quick knockout blow, the British government planned to force the Dardanelles Straits, enter the Sea of Marmara and bombard the Turkish capital of Istanbul into submission. Original Allied plans drawn up by Winston Churchill, the British First Lord of the Admiralty, called for naval actions alone. However, six months of naval bombardments and raids by marine landing parties did not have much success. The British and French squadrons operated on predictable sailing patterns, and the Turks laid a series of mine fields across their routes. On March 18, Allied naval squadrons received a terrible mauling at the hands of the Turks, resulting in three Allied battleships sunk and three more crippled. The British abruptly changed tactics and placed the Army in charge of forcing the Dardanelles Straits. British General Sir Ian Hamilton was appointed to command the Mediterranean Expeditionary Forces, which included Australian and New Zealand (ANZAC) contingents as well as English.

Liman von Sanders Takes Command

On March 24, the Turkish premier, Enver Pasha, offered Liman von Sanders command of the Fifth Army, which was being organized to defend the Dardanelles. A typical product of Prussian military upbringing—professional, aloof, and nonpolitical—Liman von Sanders readily accepted the offer and wasted no time departing for his new command. On March 26, he set up headquarters in the small port town of Gallipoli. Efforts to improve defenses at the strategic straits began at once. At the time, the Fifth Army was composed of five divisions deployed along both the European and the Asiatic coasts of the straits. Each division was made up of nine to 12 battalions, each numbering between 800 and 1,000 men. By the time of the Allied landings, another division, the 3rd, had arrived.

The Asian side of the straits, characterized by low hills and large tracts of flatlands, was more susceptible to Allied landings. The coast of the Gallipoli Peninsula on the European side consisted of very mountainous terrain with steep slopes and deep ravines. Immediately behind the beaches, the landscape was dotted with small woods and thickets. Farther inland, the peninsula became flatter and more open for maneuver. Liman von Sanders considered the Asian shore the place most likely to see an Allied landing. It was, however, the most heavily defended sector of the Turkish defenses. The Gallipoli Peninsula, on the other hand, offered only a handful of likely places to land enemy troops. One of them was the southern tip of the peninsula at Sedd-el-Bahr, completely covered by the guns of British warships. After landing there, the next immediate Allied objective inland would be the Achi Baba ridge. From this ridge, the British would be able to put a large part of the Turkish defensive works under fire.

Another likely landing place was on the north side of the Gulf of Saros, at Bulair. From this place to Maidos, the Gallipoli Peninsula is only approximately four miles wide. If the enemy could cut the peninsula along the line from the Gulf of Saros to Maidos, a considerable part of the Ottoman Fifth Army would be cut off and surrounded. In his memoirs, British Seaman Joseph Murray wrote, “No doubt the Turks were wondering exactly where and when we would strike; as invaders it was for us to choose the time and place. The Turks had to remain where they were, ready to defend their homeland.”

Reorganizing the Turkish Fifth Army

Before Liman von Sanders took command of the Fifth Army, the Turkish troops were distributed evenly along the entire perimeter of the Gallipoli Peninsula, without any reserves allocated to halt the enemy in case they breached the shore defenses. Liman von Sanders completely reorganized Turkish deployment. He pulled back the bulk of his troops, leaving company- and platoon-sized detachments to watch the possible landing sites. Since he considered the Gulf of Saros the most likely landing location on the peninsula, Liman von Sanders repositioned the 5th and 7th Divisions close to it. The 9th Division was centered on the southern tip of the peninsula and the 19th Division was placed in strategic reserve in the center. The 3rd and 11th Divisions were allocated to defend the Asiatic side of the straights. By using internal lines of communication, Liman von Sanders would be able to rush reserves to the threatened sectors.

To conceal Turkish redeployments, most movements were done during the night. Work on improving the roads began at once to prepare them for the higher traffic of supplies and reinforcements. To toughen up his troops, grown complacent in their previous static defensive positions, Liman von Sanders ordered them to conduct training marches and maneuvers. This training also had to be conducted at night to shield them from British warships, which would immediately rain shells on any group of Turks, however small.

The Amphibious Assault Begins

In the early morning of April 25, Liman von Sanders began receiving reports that hostile landings were taking place. The 3rd and 11th Divisions defending the Asiatic side reported heavy fighting with the French troops landing around the Besika Bay. At the same time, British warships lying off Sedd-el-Bahr (called Cape Helles by the British) were laying down a heavy barrage covering the landing of British troops under fire from the Turkish 9th Division. More naval gunfire soon announced further enemy landings.

Quickly dispatching the bulk of the 7th Division to the Bulair Ridge, Liman von Sanders hurried ahead of them, accompanied by his German adjutants. From the bare Bulair Ridge, they had a full view of the Gulf of Saros. While the British were heavily bombarding the area, they were not landing any troops there yet. Reports began filtering in. At the southern tip of the peninsula, the British were taking tremendous casualties but bringing in more and more troops. The Allies were not having any success against the 9th Division at Gaba Tepe. However, the British occupied the heights at Ari Burnu, to which the bulk of the reserve 19th Division under Lt. Col. Mustafa Kemal was hurrying.

Liman von Sanders estimated that his 60,000 troops were facing upward of 90,000 Allies, supported by an incredible array of warships. The Turkish high command was amazed to count almost 200 Allied warships and transports facing them. By mid-afternoon, Liman von Sanders received news that the French landing at Besika Bay has been repulsed, and that it seemed to have been a diversion. The enemy actions at the Gulf of Saros appeared to be a mere demonstration as well. The Turkish defenders put up a very spirited fight against the invading Allies. In many places, the British troops hitting the beaches were mowed down under an unrelenting hail of Turkish bullets. Many small groups of Allied soldiers managed to penetrate the shore defenses and move inland, melting away along the mazes of ravines, gullies, and thickets.

The fight was far from being one-sided, however. The full weight of British naval guns was brought to bear on Turkish positions. Rear Admiral R.J.B. Keyes recalled, “The enemy’s position was obliterated in sheets of flame and clouds of yellow smoke and dust from our high explosive. It seemed incredible that anyone could be left alive in the enemy’s position, but when the fire was lifted that ghastly tat-tat-tat of machine-gun fire broke out again, and took toll of anyone who moved.” A less exalted viewer was British midshipman H.M. Denham, who noted, “We opened fire on the Turks with twelve-pounders. I could see a dozen of them rush out of their trench, run fifty yards, lie flat with our men’s rifle bullet splashes all around them. When we directed our fire at them I saw a lot of heads, legs and arms go up in the air; however, they fought very bravely.”

The Allied Foothold

The Allies had gained a foothold at the southern point of the Gallipoli Peninsula and were constantly bringing in reinforcements. The whole of the Turkish 9th Division under Colonel Sami Bei had been committed to the fight and still more troops were needed. Liman von Sanders ordered two battalions from the 7th Division to be moved there by boat from Maidos. He also sent three battalions from the 5th Division, in readiness at the Gulf of Saros, to Maidos to follow those of the 7th Division. The 19th Division, although holding its own at Gaba Tepe and Ari Burnu, was heavily engaged against Australian and New Zealand forces.

Even though he suspected that the Allied movements at the Gulf of Saros were a feint, Liman von Sanders remained on the Bulair heights throughout the night. On the morning of April 26, he ordered units from the 5th and 7th Divisions, along with most of the field artillery of the two divisions, to Maidos for transportation to the southern tip of the peninsula. Meanwhile, he left his chief of staff, Lt. Col. Kazim Bei, in charge of the remaining troops at the Gulf of Saros. Bei had orders to send his remaining troops to Maidos if no enemy landing manifested itself the following day.

Mustafa Kemal, leading his 19th Division, was one of those rare men whom providence places at exactly the right place at exactly the right time. On the morning of the Allied landings, Kemal’s division was held in reserve approximately five miles away from the shores. Its sister division, the 9th, bore the brunt of Allied assault, and its commander urgently requested reinforcements. Kemal personally took charge of one of his regiments, a company of cavalry and an artillery battery, and hurried forward. As he later described in his memoirs, Kemal stopped on a crest of a hill to wait for his troops to catch up. While he sat resting his horse, he spotted a group of retreating Turkish soldiers from the 9th Division. They informed him that they were out of ammunition and were being closely followed by the British. Kemal quickly saw a skirmish line of British soldiers climbing up the hill. He ordered the few 9th Division soldiers to fix bayonets and lie down. He later wrote, “As they did so, the enemy too lay down. We had won time.”

The Turkish Counterattack

In the late morning, as more and more units from his 19th Division began arriving opposite the landing sites, Kemal organized a counterattack against the ANZAC positions. Leading toward the 57th Infantry Regiment, the 36-year-old officer addressed his men. “I don’t order you to attack,” he said. “I order you to die. By the time we are dead, other units and commanders will have come up to take our place.” While containing more that a little dramatic flair, Kemal’s orders reflected his correct estimation of the situation: hold at all costs.

During April 25 and the next few days, the 57th Regiment lived up to its commander’s expectation—casualties were so heavy that the regiment practically ceased to exist. To recognize the sacrifice of men of the 57th Infantry Regiment, the Turkish government did not reconstitute the unit, retiring its number with honors. Throughout the day, Kemal continued feeding reinforcements into the maelstrom. The Australians and New Zealanders tenaciously clung to their slivers of shoreline, soaking up casualties themselves and dealing out even greater casualties to the counterattacking Turks. One of the Turkish regiments advancing on the left flank, the 77th, composed mainly of unsteady Arab recruits, broke and ran after suffering severe loses. Kemal quickly shifted a battalion from the right to plug the gap. By the time night mercifully fell, the bloodied beachheads, gullies, hilltops, and slopes were littered with the carnage of war. Corpses of fallen Turks, Australians, New Zealanders, British, and Arabs presented a nightmarish landscape. The moaning of wounded made it seem as if the hills themselves were crying out in anguish.

While Kemal’s division suffered terrible losses, he scored a moral victory over the Allies. The casualties among the Australian and New Zealand soldiers were also so great that their brigade and divisional commanders convinced Maj. Gen. William Birdwood, commander of the Anzac contingent, to request that they be evacuated. The expedition’s commander, British General Sir Ian Hamilton, denied the request, instead advising, “You have got through the difficult business, now you have only to dig, dig, dig, until you are safe.” As ANZAC shovels bit into the rocky soil, the Allies lost the initiative.

Containing the Beachhead

All through the fighting on April 25, Kemal managed to contain the Allied advance. For his role in events, he would be awarded the Turkish Order of Distinguished Service. Later, Kaiser Wilhelm II would award Kemal Germany’s Iron Cross. Extremely outspoken and nationalistic, Kemal soon came to disagree with the overall commander at Gallipoli, Liman von Sanders, who preferred to have German officers in key positions. Kemal’s attitude and language in addressing his Turkish and German superiors were not always the most politic. Despite multiple ruffled feathers, his personal courage and abilities were never in doubt, and on May 1 he was promoted to the rank of full colonel.

Heavy fighting continued for the next two days. The Allies, intent on breaking through to the hinterland of the peninsula, threw more and more men into the fighting. For their part, the Turks were just as determined to push the invaders back into the sea. As the result, neither side gained their objectives. By the beginning of May, stationary warfare, reminiscent of Western Europe, had developed on the peninsula. Despite large quantities of blood shed on both sides, progress was measured in feet. Two distinct fronts soon took shape: at Sedd-el-Bahr (Cape Helles) and Ari Burnu (Anzac Cove).

To minimize the effectiveness of British naval gunfire, Liman von Sanders ordered his troops in the first line to dig their trenches as close to the British as possible. With the opposing trench lines within a grenade’s throw from each other, British naval gunfire could just as easily hit a friend as a foe. However, the British ships still could rain heavy fire onto Turkish second and subsequent lines of defense. Turkish villages and small towns on the Gallipoli Peninsula were turned to rubble by British naval gunfire. The once-beautiful port town of Maidos was left in ruins. The town of Gallipoli was severely damaged. Krithia, located just one mile north of the battle lines at Sedd-el-Bahr, was reduced to a heap of rubble. Allied warships, cruising the waters of the Aegean Sea with impunity, were able to bring a punishing flanking fire across almost the entire peninsula. Especially hard hit were the Turkish flanks, resting on the Aegean Sea in the west and the Dardanelles in the east.

The Defenders Resupply

The resupply situation of the Turkish Fifth Army was extremely difficult. The railhead nearest to the front lines was at a small town of Uzun-Kupru in Thrace (modern-day Bulgaria). Since the Turkish Army had no trucks, all supplies had to be moved by horse- and ox-drawn wagons, a journey of several days. The overwhelming majority of supplies coming to Gallipoli arrived by boat from the Asiatic mainland across the Sea of Marmara. As British and Australian submarines tried unsuccessfully to close the supply line, the Turkish Army continued the struggle. At the beginning of the campaign, even entrenching tools were hard to come by. During their attacks on the British trenches, Turkish infantrymen often carried away any digging implements they could capture and scavenged wood, bricks, and other materials from destroyed villages. Even sand bags were in short supply. When several thousand of them did arrive, large numbers of the precious items were used to patch up the ragged uniforms of the Turkish soldiers.

Four more Turkish divisions—the 4th, 13th, 15th, and 16th—arrived to reinforce Liman von Sanders’s depleted command. These divisions brought several batteries of much-needed heavy artillery. Even though consisting mostly of older models, the guns proved invaluable in counteracting British artillery, which was being landed on the peninsula in increasing numbers. The Turkish Navy, particularly its two German-crewed ships, contributed two machine-gun detachments of 12 weapons each to the Gallipoli defenses.

During the night of May 18, the newly arrived Turkish 2nd Division attacked the Allies at Ari Burnu. It succeeded in breaking through the first British trench line and reaching the second. However, the British immediately counterattacked and pushed the exhausted 2nd Division back to its starting position. Casualties on both sides were heavy, with the 2nd Division losing 9,000 men killed and wounded. In his memoirs, Liman von Sanders took the blame for the attack’s failures, citing insufficient artillery preparation and quantity of ammunition. British losses were significant as well, and British command requested a cease-fire to collect and bury their dead. Liman von Sanders agreed to halt the hostilities for one day on May 23.

At the end of June, a provisional German company of 200 commissioned and noncommissioned officers joined the Fifth Army. However, the unfamiliar climate and Allied fire quickly reduced its numbers. Distributed in small groups along the whole front, the Germans nevertheless proved invaluable in supervising Turkish engineering and construction efforts. A significant weakness in Turkish positions was the gap between the Ari Burnu and Sedd-el-Bahr fronts. While the Turkish flanks at Sedd-el-Bahr were anchored on the water, the flanks at Ari Burnu were hanging in the air. Advancing through the Anafarta Valley, the Allies could threaten both Turkish fronts and cause them to give up their positions.

The Allies Reinforce

At the beginning of August, five fresh British and ANZAC divisions were landed at Ari Burnu and Suvla Bay. In the evening of August 6, Liman von Sanders received alarming reports that a strong Allied force was moving north along the coast from Ari Burnu, aiming at the Anafarta Valley. Immediately, he moved troops from the Turkish 9th, 7th, and 12th Divisions to parry the new threat. As the forward elements of the 9th Division reached the Koja Chemen Mountain, they discovered that the British infantry was advancing up the opposite slope of the same mountain. In a brief and decisive counterattack, the Turks completely drove the British off the mountain. Leading from the front, German Colonel Hans Kannengiesser, commander of the 9th Division, was killed by a bullet through the chest.

Heavy fighting for the hills around the Anafarta Valley continued through August 7, as the outnumbered Turkish soldiers from the 9th Division hung on waiting for reinforcements. After a grueling forced march, the 7th and 12th Divisions reached the threatened area the next day. Liman von Sanders appointed Kemal the overall commander of all Turkish forces on the Anafarta Front. His six divisions, centered on the two villages, Great and Little Anafarta, became known as the Anafartalar Group (“Anafartalar” in Turkish is plural for Anafarta). Throughout August 9, Kemal launched attack after attack at the British lines. In extremely bloody fighting, the Allies were pushed back to the coast in several places. Not lacking in bravery, the British and ANZAC troops tenaciously hung on to several key pieces of hilly terrain. On the evening of August 10, Kemal personally led another attack. After a difficult contest, the British were driven off all the dominating terrain at the head of the Anafarta Valley.

During the attack on August 10, Kemal was hit in the chest by a spent piece of shrapnel. Fortunately for him, the shrapnel struck his pocket watch, leaving him unscathed. He later presented this watch to Liman von Sanders, who in turn gave Kemal his own watch, bearing his family’s coat of arms. On August 15, the Allies launched their own strong attack from Suvla Bay northeast toward the Kiretch Tepe Ridge. Their initial attack was a success, driving the Turks off a large portion of the ridge. A Turkish battalion composed largely of policemen from the Gallipoli Peninsula bore the brunt of the attack. It was almost completely annihilated, and its commander, Captain Kadri Bei, was killed.

A Grinding Stalemate

Throughout August 16, the British continued heavy pressure on the beleaguered Turks. Turkish reinforcements were rushed forward and had to attack in daylight, in full view of supporting British warships. Turkish casualties from flanking naval gunfire were frightening, but the Allied ground advance was held up at all points. On August 21, the British launched another all-out attack against the Anafarta Valley. The fighting was as futile as it was bloody. The Allies made no progress, losing 15,000 men killed and 45,000 wounded. Turkish losses were equally frightening, forcing them to commit the last reserves, including the dismounted cavalry.

Had the British been able to break through the Kiretch Tepe Ridge onto the wide Anafarta plain, the Turkish Fifth Army would have been outflanked and forced to stand and die or else fall back, ceding the Gallipoli Peninsula to the British. As it was, due to the incredible tenacity of the Mehmetciks (Turkish equivalent of American doughboys), the British merely extended the front lines at Ari Burnu. Liman von Sanders attributed their failure to the timidity of British commanders in waiting too long at the coast before pushing inland. The British, for their part, underestimated how quickly the Turks could rush reinforcements to the threatened sectors.

On September 20, Kemal fell ill with malaria. Upset over real or imagined slights, he offered his resignation on September 27. While Liman von Sanders attempted to smooth over matters, Kemal remained unpersuaded. His relations with the German commander continued to deteriorate. On December 5, Liman von Sanders granted Kemal unconditional medical leave.

The Allied Withdrawal

The fighting at Anafarta was the high point of the almost nine-month campaign, although the Allies continued half-hearted attacks throughout September and October. At the end of October, the Allied command began planning the evacuation of their troops from Gallipoli. An Austrian mortar battery arrived in mid-November, followed by an Austrian howitzer battery in December. The Austrian gunners, well-trained and -equipped, contributed significantly to the Turkish defenses in the later stage of the campaign. Along with approximately 500 Germans, the Austrian artillerymen were the only non-Turkish troops fighting the Allies at Gallipoli.

Toward the end of November, the Turkish forces gathered for a decisive counteroffensive on the Allied positions. Their objective was to pierce the junction between the Ari Burnu and Anafarta fronts. Mock defensive positions were constructed behind the front and Turkish divisions assigned to participate in the attack were rotated back to practice offensive operations. However, before the offensive was launched, the Allies evacuated the Ari Burnu and Anafarta fronts. The Allied command planned and executed the withdrawal so skillfully that the Turks never realized what was about to happen. During the night of December 19, under covering fire from British warships, Allied land forces slipped away from the blood-soaked beaches. Liman von Sanders praised the Allied efforts: “The withdrawal had been prepared with extraordinary care and carried out with great skill.”

While the Allies evacuated their men from Ari Burnu with hardly a loss, they had to leave behind a trove of supplies and war materiél: ammunition, tents, spare parts for cannons and machine guns, canned food, hand grenades, even a few small steamers and more than 60 rowboats. Supply-starved Turkish forces distributed the booty among all theaters of operation. Now Liman von Sanders was able to concentrate all of his forces against the only remaining Allied beachhead at Sedd-el-Bahr. The Turks kept up a steady pressure on the British lines, watchful for any further sign of withdrawal. When an Allied pullback was detected during the night of January 8, the Turks launched a determined effort to trap as many British troops as possible on the beaches. The British rear guard put up a spirited fight, aided by booby traps, land mines, and naval gunfire. In spite of losing many men, the Allies once again achieved an orderly withdrawal and evacuated Sedd-el-Bahr.

By the morning of January 9, jubilant Turkish forces held the whole peninsula. An even greater amount of war booty had been abandoned on the southern tip of the peninsula. Ragged Turkish soldiers gleefully fell upon the riches the British left behind. Liman von Sanders recalled, “What the ragged and insufficiently nourished Turkish soldiers took away cannot be estimated. I tried to stop plundering by a dense line of sentinels, but the endeavor was in vain. During the ensuing time we saw the Turkish soldiers on the peninsula in the most incredible garments which they had made up from every kind of uniform. They even carried British gas masks for fun.”

Counting Losses

During the height of the Dardanelles campaign, Liman von Sanders commanded 22 infantry divisions in the Fifth Army. Turkish losses amounted to 66,000 men killed and 152,000 wounded. Of those wounded, 42,000 soldiers were later returned to duty. Allied casualties reached upward of 200,000 men killed, wounded, or missing in action. The men evacuated from the Gallipoli beaches later were shipped to France, smack into the bloodbath of the Western Front trenches.

As for Gallipoli, it would be difficult to find another location where so many men from so many nations fought and died in such a small place. Turks, Germans, British, Australians, New Zealanders, French, Indians, Senegalese, Arabs, Austrians, Gurkhas, and others were locked in mortal combat where bravery was never in short supply. Years later, while serving as the president of Turkey, Mustafa Kemal would write: “Those heroes that shed their blood and lost their lives … you are now lying in the soil of a friendly country. Therefore rest in peace. There is no difference between the Johnnies and the Mehmets to us where they lie side by side now here in this county of ours. You, the mothers, who sent their sons from faraway countries, wipe away your tears; your sons are now lying in our bosom and are in peace. After having lost their lives on this land they have become our sons as well.”

It would have been nice if some of the places mentioned in the story were placed on the map. Like Bulair Ridge, Ari Burnu and even the famous Achi Baba ridge. A more detailed map would have made a good article even better.

I never knew Kemal made those statements as president. What an incredibly kind, thoughtful, beautiful, and healing thing to say! Not only was the man brave, he was clearly very compassionate as well.

It’s sad to see the sentiments of Kemal being rejected by his Islamist successors in modern-day Turkey.

What a terrible waste, on both sides.