By Keith Milton

For nearly a century, England and the Netherlands were longtime allies in the Eighty Years’ War against the Spanish Empire. The last major clash of that war was the Battle of the Downs in 1639, at which an all-Dutch fleet commanded by Admiral Maarten Tromp defeated a Spanish armada four times its size under the very guns of England’s forts at Dover. Looking on that day, but taking no active part in the action, was an English fleet under Admiral Sir John Pennington. Pennington was under strict orders from the English King Charles I to prevent the combatants from conducting a battle in English waters and to go to the aid of whichever party was fired upon first in violation of his edict. Pennington failed to do so, mainly because Tromp had foresightedly assigned a squadron of 30 ships to keep an eye on Pennington and prevent any English interference. The battle was over before Pennington had time to act. The Spanish lost 40 ships and 7,000 men—and with them, any further claim to being a major sea power.

King Charles took a dim view of this blatant disregard of his orders and sent Pennington to the Tower of London for his signal failure to prevent the battle. The king’s ire against Holland was short-lived, however. A Dutch emissary visited England, smoothed over Charles’s feelings and, as a bonus, arranged a marriage between the two royal houses. Had Charles remained in power, it is likely that the inevitable differences between the two nations would have continued to be resolved peacefully, but that was not to be. Charles became embroiled in a protracted struggle with his own Parliament that quickly evolved into a full-blown civil war. Parliament eventually won the war and Charles was beheaded in January 1649. His son, who later would become King Charles II, took refuge in Holland along with many of his Royalist followers, much to the displeasure of Parliament and its new Lord Protector, Oliver Cromwell.

“God Will Yet Humble Their Pride”

While the English were busy fighting among themselves, the Dutch greatly expanded their maritime trade, enlarging their navy and merchant fleet and rising to a dominant position on the world’s oceans. “The Hollanders have well nigh beaten all nations, by traffic, out of the seas, and have become the only carrier of goods throughout the world,” one Dutch official boasted. This was not quite the case, although the Dutch merchant fleet contained more vessels than the rest of Europe combined. Their cross-Channel rivals, the English, resented the growing Dutch military and mercantile power, as well as the continuing refuge they provided for the king’s fugitive son and his Royalist court. The chief bone of contention, however, was commercial. As one neutral observer noted, “The Dutch have too much trade, and the English are resolved to take it from them.” A Swedish diplomat stationed in London succinctly summed up the burgeoning rivalry: “Both these nations, and especially this one here, are insufferably arrogant. It is possible that God will yet humble their pride.”

Still preoccupied with consolidating his power at home, Oliver Cromwell at first felt disinclined to challenge the Dutchmen, but events soon changed his mind. His ambassador to Holland was repeatedly insulted by Royalist sympathizers who shouted “King killer!” at him. Later, one of the ambassador’s staff was assassinated as he sat having his evening meal at his hotel in The Hague. While it was generally believed that a group of Royalists had been responsible for this crime, the killers were never apprehended. Although the Dutch authorities offered a large reward to crack the case, the unsolved murder only served to worsen relations between the two seafaring countries.

After the Battle of Worcester in July 1651, where Cromwell and his New Model Army completely routed the last of the Royalists, the English Civil War finally ended. Parliament then turned its full attention to the Netherlands, with a vengeance. It passed the Navigation Act of 1651, which required all imported goods to be carried into English ports by English ships or by those of the exporting countries. This was a tremendous blow to Dutch merchants and ship owners, whose own vessels transported freight from the Netherlands, its far-flung colonies and other countries throughout the world. Later that same year, Parliament began issuing letters of marque to English merchants and ship owners who felt themselves aggrieved by the Hollanders. Thus legally empowered to recover their losses from Dutch vessels, British privateers and warships began stopping and seizing whatever cargoes struck their fancies.

Admiral Tromp Dispatched 50 Ships to Protect the Nations Merchant Vessels

The final blow came when Parliament reasserted its age-old sovereignty over the “British Seas,” granting the Commonwealth Navy absolute dominion of any and all ships sailing the ocean between the North Sea and Cape Finisterre, off the Spanish coast. In almost the same breath, Parliament notified the Dutch that their ships could no longer traverse the Caribbean Sea. And when British Admiral Sir George Ayscue arrived in Barbados in October 1651 to take control of the colony for the Commonwealth, he immediately seized 27 Dutch vessels, claiming they had violated the embargo by trading with the Royalists.

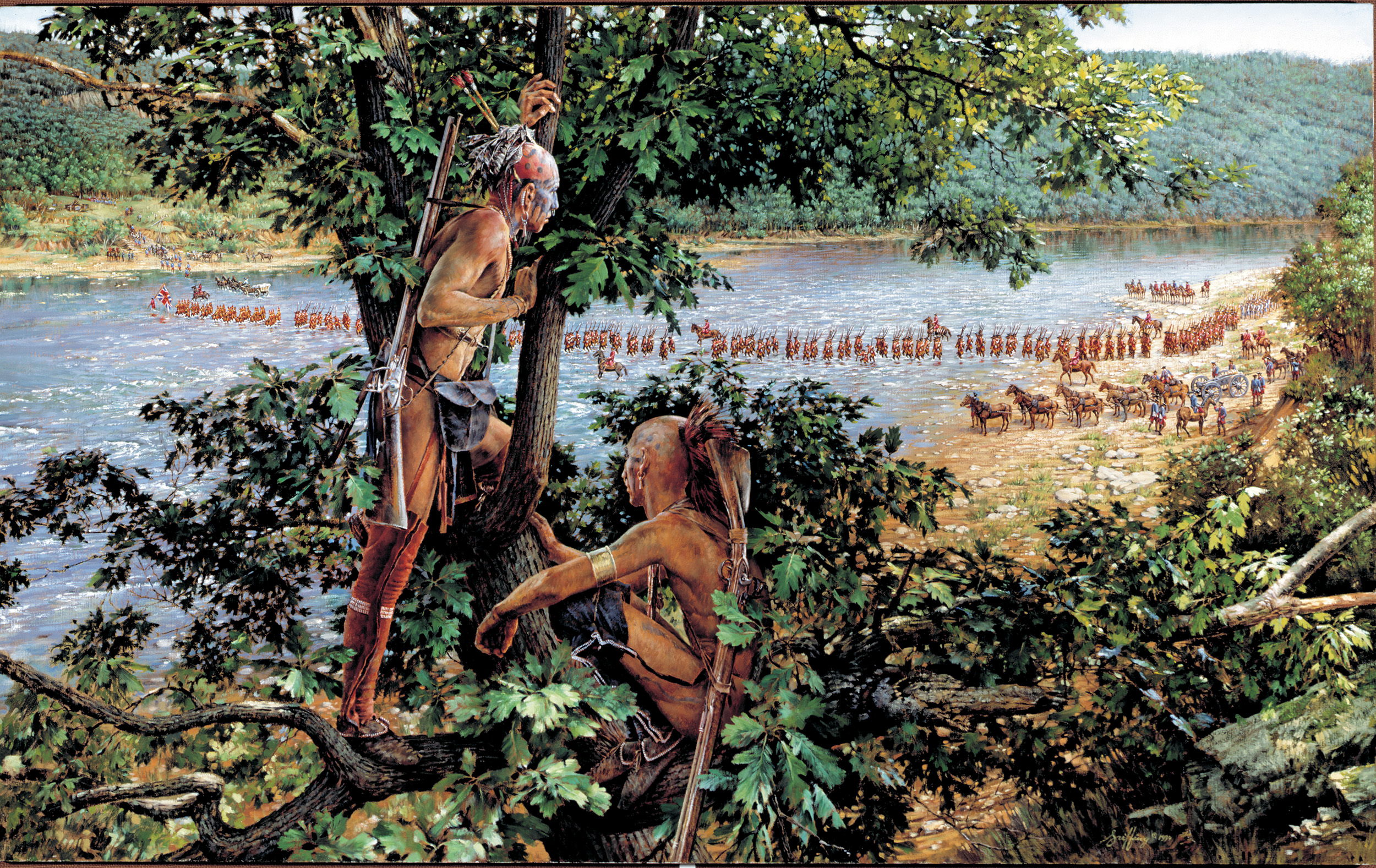

In response to these multiple provocations, the Netherlands States General passed a resolution of its own to raise, arm, and send out a new fleet to protect Dutch interests at sea. Admiral Tromp, now commander-in-chief of the Dutch Navy, was dispatched with 50 ships and told to do whatever he felt was necessary to safeguard the nation’s multitudinous merchant vessels. He was cautioned, however, not to do anything provocative and to avoid the English shoreline wherever possible. Tromp stationed his fleet near the Flemish shore between Dunkirk and Newport. While waiting there, a severe three-day storm arose and damaged his fleet. In order to effect repairs, Tromp was forced to seek calmer waters in the leeward shelter of the Dover Hook. Immediately upon arrival, he sent word to English Admiral Nehemiah Bourne, who was anchored nearby, explaining his reasons for approaching the English coast and assuring Bourne that he would leave as soon as his repairs were completed. Bourne offered no objections—as a fellow seaman he could understand Tromp’s predicament. The repairs were completed in a few days and, true to his word, Tromp moved his fleet back over to the French side of the Channel.

Near Calais, Tromp learned that seven Dutch East Indiamen with highly valuable cargoes were approaching the Channel. At the same time, he was warned that a second English fleet commanded by Admiral Robert Blake was lying in wait for the Dutch merchant ships. Tromp immediately changed course to put himself between the two fleets and almost simultaneously encountered 15 British warships, one of which carried the broad pennant of an English admiral—Blake. Holding course, Tromp was determined to protect the Dutch cargo ships. Still hoping for a peaceful outcome to the encounter, he prepared to formally salute the English man-of-war, as the Navigation Act required, but before he could do so, a cannonball tore through his fore topsail. Tromp did not answer the shot, but prepared to send his flag captain in a longboat to ask for an explanation of the belligerent act. As the boat was being lowered, another shot came through the starboard mizzen shrouds and carried away one of the stays from his flagship, Brederode.

Before the longboat was even in the water, a third shot from Blake’s flagship, James, tore through the side of Tromp’s flagship, took off the arm of a Dutch gunner, and wounded five others with flying splinters. Even then, Tromp tried to avoid a pitched battle, sending a warning shot across the bow of Blake’s vessel while the longboat bearing his emissary beat through the waves toward the English commander. Instead of waiting for Tromp’s captain to come aboard for a parley, Blake swung around and sent a full broadside into Brederode’s side. Tromp, seeing that he had no choice, hoisted a red battle flag signaling a general attack. The two flagships, with more than a hundred guns between them, led a swirling melee that continued for four hours as crowds gathered on the chalk-white cliffs of Dover to watch the world’s two foremost sea powers squaring off for the first time. As the battle reached a full crescendo, Bourne heard the cannonading and brought his 12 ships to Blake’s aid, attacking Tromp from the rear. The fighting continued until darkness brought the battle to a close.

The Dutch Braced Themselves for War

At first light, Tromp and his captains were amazed to discover that Blake and Bourne had quit the area during the night and withdrawn to the shelter of the Dover Hook, towing with them the captured Dutch ship St. Laurens. His fighting blood aroused, Tromp yearned to give chase, but quickly thought better of it and conveyed the Indiamen and their valuable cargoes safely to the Netherlands. He immediately fired off a letter to Blake, whom he had known for several years, asking him “for friendship’s sake” to return the St. Laurens and her crew. Blake replied angrily that Tromp had committed a “great insult” to him by not “employing the customary respect which the occasion demanded,” meaning, presumably, that Tromp had not saluted the English colors. Captured Dutch Captain Bastiaen Tuynemans supported Blake’s version of events, although his obvious bitterness at being left behind undoubtedly colored his testimony. Back home, the Dutch braced themselves for war.

In July 1652, Tromp reentered the English Channel with 83 men-of-war and nine fire ships. He had received word that Ayscue and 31 English warships were waiting to attack him in the Downs. Meanwhile, Blake had headed north with another 61 ships to harass the Dutch herring fleet in the North Sea. Tromp originally intended to deal with Ayscue first before going after Blake, but a change in the prevailing winds made that impossible. He decided to venture north instead, but ran into a bad storm that forced six of his ships ashore, where they became easy prey for scavenging English coast watchers. Greatly dismayed, Tromp returned to harbor at Amsterdam with less than half the ships he had taken to sea (most managed to limp home later) and pronounced himself “extraordinarily punished by the mighty hand of God.” The States General, surveying the damage and discovering that Tromp had not traded even one shot with the enemy, summarily relieved him of command and placed his old comrade, Admiral Witte de With, in command of the fleet. Tromp was crushed by the news but did not complain.

Temperamentally, de With was the complete opposite of Tromp. While courageous to the point of foolhardiness, his fiery temper long since had made him unpopular among his seamen, and the sailors aboard Tromp’s old flagship absolutely refused to allow de With onboard. He had to set up command in an East Indian merchant ship, Prins Willem, instead. In early October 1652, accompanied by Admiral Michiel de Ruyter, de With sailed off in search of the English fleet. He found the English, again under Blake, heading straight for him near the Kentish Knock, a prominent sandbar in the Thames estuary. Once again the weather conspired against the Dutch, as shifting winds allowed the English vessels to tack away from danger and envelope the Netherlanders in a pincer-like grip. After three hours of uneven combat, the Dutch broke off the fighting and limped away, having lost one ship to sinking and another to capture. Fully a third of de With’s 62 ships had refused to fight at all, demonstrating their manifest dislike for the martinet admiral. “They seem in every way to try to show the white feather,” de With complained with some justification. “Never in all my life have I seen such cowardice among sea captains as these have shown.”

Almost 100 Warships Convoyed the 270 Merchants Past Southern Britain

Belatedly realizing their mistake, the States General went back to Tromp and requested that he resume command of the fleet. Tromp accepted, although not before making public his misgivings over “subtle questions by ill-disposed and hostile persons” in the government. Having bested his political rivals at home, Tromp set out to even the score with his naval rivals at sea.

In December 1652, Tromp set out with 90 warships and eight fire ships to convoy a fleet of 270 merchantmen past the southernmost point of Britain and see them safely on their way. Before he had even cleared Ostend, however, Tromp received word that his old adversary Blake was lying in wait off the Downs with half the English fleet. Tromp divided his fleet into squadrons, with himself in the van, de Ruyter in the center, and Vice Admiral Jan Evertsen in the rear. Not waiting to be attacked, he had determined to take the entire fleet to the Downs, merchantmen and all, and pitch into Blake before he had time to act.

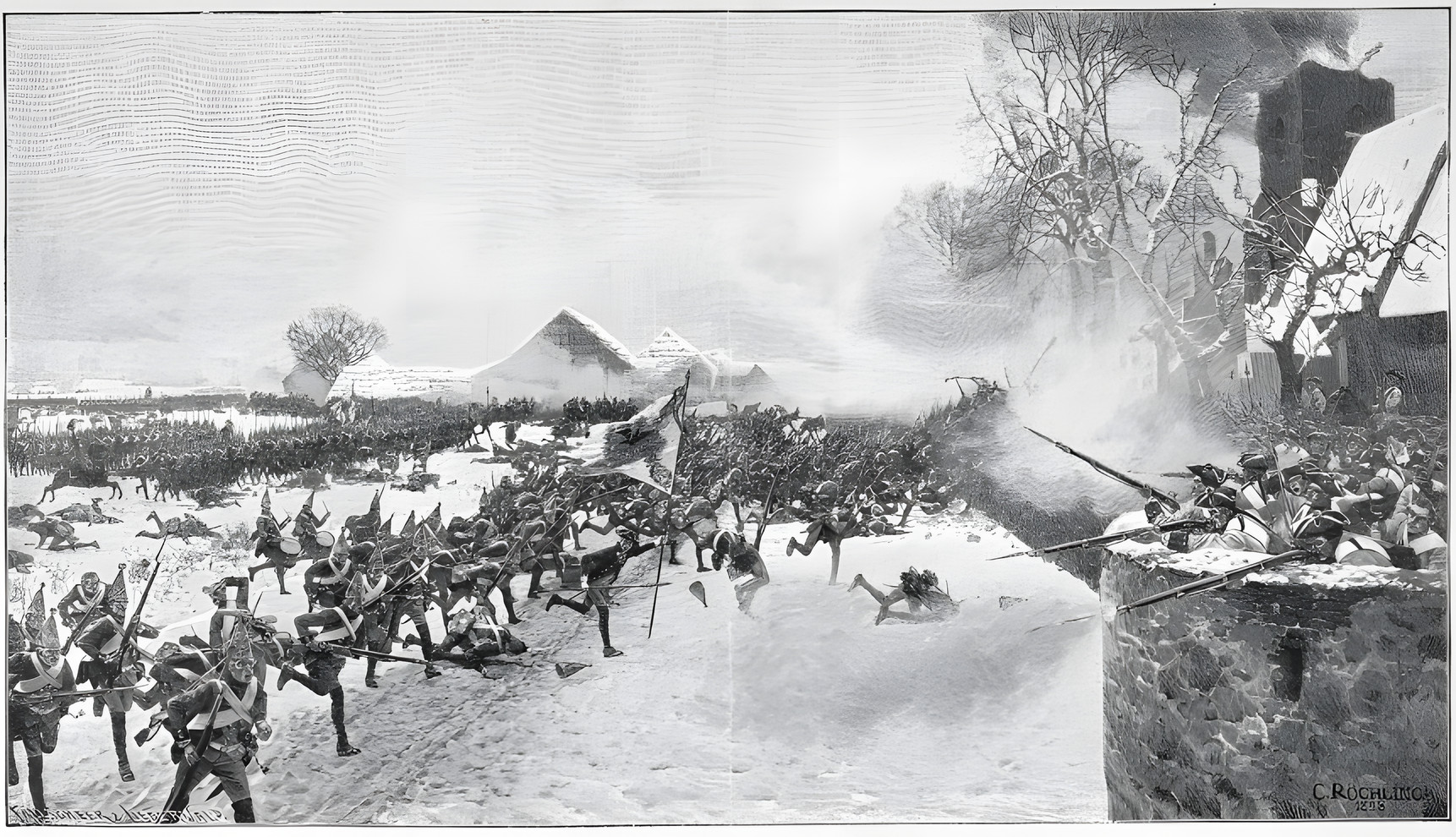

Once again, a strong gale thwarted Tromp’s plans and forced a return to the Flemish coast. The weather was still bad, and he left the merchant fleet under the protection of one of his squadrons while he and the rest of the Dutch fleet returned to the Dover area and anchored for the night. The next day the seas were still high and the gale was still blowing, but Tromp had sighted his quarry and put out the signal for a general attack. At first, Blake seemed unwilling to engage Tromp during a storm, but Tromp had the weather gauge and gave his enemy no choice. Some of Tromp’s swifter vessels were already overtaking the flanks of Blake’s fleet and giving them a pounding. Blake ordered his ships to come about and engage the Netherlanders.

As the two admirals passed each other, they exchanged broadsides. Tromp then came about to give Blake his other broadside, and in so doing collided with the English ship Rosekrantz, which was in the act of crossing his bow. Brederode’s bowsprit was torn off, along with part of the bow section, when her rigging became entangled with the English ship. Tromp at once ordered “Boarders away!” and his sailors clambered onto Rosekrantz to clear away the tangled rigging. Another English vessel, Bonaventure, laid alongside Brederode’s other flank and began belaboring her with fire and boarders. For nearly half an hour, Tromp’s crew fought fiercely against the double envelopment until Evertsen became aware of his commander’s plight and hurried to his aid. Laying alongside Bonaventure, Evertsen’s guns blazed away and in short order destroyed the English ship’s main and mizzen masts. Dutch sailors boarded the now-helpless Bonaventure and made her a prize, then crossed over Brederode and forced the surrender of Rosekrantz.

The Self-Appointed ‘Sovereign of the Seas’

Meanwhile, Blake had run afoul of de Ruyter and lost his main topmast. As de Ruyter sheered off to gain a better position, Blake was attacked by two other Dutch ships. Twice they boarded him, and twice he forced them back. Blake, desperate to avoid capture, blew up his own deck, sending friends and foes alike flying into the air. He, too, was wounded during the last-ditch action, after which he and his surviving fleet broke off action and headed for Dover Hook. The oncoming darkness brought the battle to a close as both fleets retired to lick their wounds. Tromp’s crewmen spent the night repairing their vessels to resume battle in the morning. But the cold light of day revealed not a single British ship in the area. Blake had ascended the Thames with the remnants of his fleet, leaving behind two captured ships, three sunk and six reduced to riddled hulks by the more numerous Dutch vessels. As the weather improved, Tromp escorted all 270 of the merchantmen in his charge safely on their way to their various ports of call.

After routing Blake, Tromp was said to have fastened a broom to his fore topmast to indicate that he had swept the seas clean of the enemy. There is no proof that he did this—it seems somewhat out of character for the humble Tromp—but he could have said with some truth that he had driven the self-anointed “Sovereign of the Seas” from his own coastal waters and cruised the enemy coast with impunity for several weeks. Tromp became almost as large a hero in England as he was in his home country, and his tactics for outmaneuvering Blake would be widely studied for years to come.

Meanwhile, Blake’s shocking defeat and withdrawal caused such a furor in England that Oliver Cromwell himself went down to the docks at Spithead, arrested several captains, and assessed heavy fines against them for their alleged cowardice. George Ayscue accused Blake of deserting him and resigned in protest. Blake’s own brother, Benjamin, was one of six English captains subsequently dismissed from the service. At the same time, Parliament set out to build a newer, stronger fleet to hunt and Tromp and confiscate the merchantmen he was convoying with such impunity through the English Channel. While the ships were being built, press gangs scoured every seaport in England to round up crews for the fleet. Once manned, provisioned, and fitted out, the fleet was placed under Blake’s command, with Cromwell’s old and trusted Civil War comrades, Richard Deane and George Monck, piped aboard to assist him as generals-at-sea. The two newcomers were inexperienced in naval service, but of undoubted courage. Vice Admirals William Penn and John Lawson were put in command of the lesser squadrons, where their experience would help protect Blake’s flanks.

During the first week of February 1653, Tromp escorted a large convoy of merchantmen southward through the Channel and saw them safely on their way to the Mediterranean and other destinations. He then approached the French coast and anchored his fleet off La Rochelle to repair and resupply his ships while he waited to rendezvous with an inbound fleet of merchantmen he was to convoy northward. By February 20, he had gathered a total of 152 homeward-bound freighters, but contrary winds held up their departure for three days. The Dutch fleet finally got under way on the 24th. Four days later, they were off Portland when they spotted Blake’s fleet attempting to cut them off. In spite of being hampered by the merchant ships, Tromp put out the signal for a general attack and made straight for his enemies. His ships had the wind in their favor and were soon engaged with Blake’s flanks.

“Once On Board, Always On Board”

Tromp, aboard Brederode, went straight for Blake and his flagship Triumph, delivering a broadside at pistol-shot range. Tacking swiftly around, he put in a second broadside before Blake’s gunners could recover from the first. He then reversed course and delivered yet another broadside to Blake’s uninjured side. Blake found this hail of iron too hot for comfort and sheered off from contact. He fought the rest of the day’s battle at long range. By now both fleets were at grips with each other, and the action quickly became furious. The sky was shrouded by smoke from the guns and fires aboard some of the ships. The cries of the wounded, the howling of the wind, and the whistling of cannon shots could be clearly heard above the tremendous thunder of the guns. The hills on both sides of the Channel echoed with the sounds of battle.

De Ruyter and his squadron attacked the English rear and he soon engaged its largest vessel, Prosperity, which fired so fiercely that de Ruyter determined to board her. He locked yardarms and ordered, “Boarders Away!” But the Dutch boarders were forced back to their own vessel, where de Ruyter met them with withering scorn. “What’s this, boys?” he cried. “This will never do. Once on board, always on board. Hurrah, over you go again!” Back they went, renewing the fight with such vigor that they eventually forced Prosperity’s surrender.

Several ships of Prosperity’s squadron saw de Ruyter making off with his prize and crossed his bow to contest his takeover. Against the odds, de Ruyter fought with skill and courage, but he could not last much longer. His fellow townsman, Jan Evertsen, saw de Ruyter’s plight and rushed to his aid, attacking the surrounding British with such fury and determination that three of the enemy vessels sheered off and the beleaguered de Ruyter was able to fight his way out. In another area of the action, Captain Adrian Cruyck, commanding the 40-gun Ostrich, was engaged with six of Penn’s ships. Although he was giving as good as he got, Cruyck’s decks were soon running with blood and his ship was badly knocked about. But he had damaged one of Penn’s ships so badly that she could no longer be fought, and Penn drew off toward the Isle of Wight. Another ship was dismasted and had to be towed out of the fight.

Tromp saw Cruyck’s perilous situation and dispatched help, but all they could do was take off the few remaining crewmen and leave the battered Ostrich to her fate. The valiant Cruyck had been killed, and the wreck of his vessel finally washed ashore in the vicinity of Portsmouth. Another Dutch captain, seeing his battered vessel being grappled and boarded on either side by English ships, blew up his magazines and sent his own and both enemy ships to the bottom. Another Dutch ship, Gate of Troy, captured an English vessel after a hard fight, but her crew, upon discovering a large quantity of fine wine aboard, paused to refresh themselves. While partaking of the heaven-sent bounty, they became drunk and failed to notice that their prize was sinking. She went to the bottom, taking Gate of Troy and her less-than-observant shipmates with her.

After the Battle Tromp Held a War Council Aboard His Vessel

It was by now late afternoon, and Tromp noticed several of the swiftest enemy frigates heading for the French coast where the Dutch merchantmen were gathered. He quickly sent several of his captains to intercept them and drive them back to their own coast. Darkness brought an end to the day’s battle. That night Tromp held a council of war aboard his flagship. His captains were in favor of a general attack at first light, but many of their own vessels were nearly out of powder and shot, and Tromp opted to take a more defensive posture. The fight would be continued with the warships ringing the merchantmen in an arc-shaped formation, one of Tromp’s favorites, and they were all advised to be sparing with their remaining ammunition.

The night was spent in making repairs wherever possible, and the Dutch vessels lowest on ammunition were partially replenished by the only supply ship in the fleet. The next morning found the English fleet with the advantage of the wind bearing down on the Dutchmen. Action was joined at 10:30, and it was a repeat of the ferocious activity of the previous day. Five times Blake attempted to break the Netherlanders’ line, and five times he failed. Tromp, Evertsen, and de Ruyter were always at the points of greatest danger and gave heart to their seamen. Had they not had the merchant fleet to contend with, they might have gained victory then and there, but some of the merchantmen panicked and left the protection of the Dutch fleet for the French coast. Tromp ordered them to return, and if they had obeyed, not a sail would have been lost. As it was, a dozen merchantmen continued to flee in defiance of the orders and were overtaken by some of Blake’s swiftest frigates.

Night ended the second day of battle, and both sides took advantage of the respite to rest their exhausted crews. Several of Tromp’s captains reported that they were completely out of ammunition, but Tromp had none left to give them. Their ships were ranged among the freighters for additional protection. When the battle resumed the next day, Blake again enjoyed the advantage of the wind and once more tried in vain to break Tromp’s line. The Dutch fought gallantly, and de Ruyter’s almost dismasted hulk gave a good account of herself, until she was completely helpless and had to be towed out of the fight. After a couple hours, half the Dutchmen were out of ammunition, and several of them started to withdraw. Tromp sent a few shots after them and asked if they had turned coward. They returned and Tromp ordered them to arrange themselves along the edges of his arc formation next to the merchantmen.

A Bitter Victory for the British

By this time Tromp had only 27 ships capable of fighting. As the English came down with the wind just before sunset, they gave such a good account of themselves that they nearly pierced the English line. After another hour of fighting, the fiercest of the three days, Blake unexpectedly drew off—to the immense relief of the Netherlanders. Had he known that the Dutchmen doing most of the firing only had enough ammunition left for a half-hour more, he might have captured not only all of the merchantmen, but most of the warships as well. But at the height of the battle Blake was badly wounded in the thigh, and the order for withdrawal was given—whether by him or the officer who replaced him was never known. The three-day Battle of Portland was over.

When the English fleet sailed out to resume the action the following day, they found the seas empty. Tromp had guided his battered fleet through the coastal shallows, which he knew well, and brought them safely into harbor. Both sides claimed victory, but the Dutch had quit the field, leaving behind eight warships and 50 merchantmen. The English were not overly thrilled by their victory, which had seen Tromp escape to fight another day, but for the time being English control of the Channel was restored. And when Tromp next ventured out to contest that control, at the Battle of Schveningen, near The Hague, in July 1653, he would meet his fate in the form of an English musketball, calling from his deathbed: “I am finished. Keep up your courage.” The First Anglo-Dutch War would end a few months later.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments