By Roy Morris Jr.

Union General William T. Sherman, not the easiest man to please, always held Colonel Benjamin Grierson in high regard. The former Indiana music teacher, said Sherman, was “one of the most willing, ardent and dashing cavalry officers I ever had. He handled his men with great skill, doing some of the prettiest work of the war.”

A dicey incident on the Western plains five years after the Civil War did nothing to lessen Sherman’s soldierly regard for Grierson. At Fort Sill, Oklahoma, in May 1871, Grierson found the perfect opportunity to repay the general for his kind words and good opinion. Always a cool head in a crisis, Grierson’s quick actions that day would help Sherman hold onto his.

Grierson at Fort Sill

By then Sherman had succeeded his good friend Ulysses S. Grant, now President Grant, as commanding general of the U.S. Army. Through Sherman’s personal intercession, Grierson obtained command of Fort Sill, leading the all-black 10th Cavalry Regiment in the ongoing campaign against restive Native Americans on the plains.

Sherman had gone west to investigate recent depredations by Kiowa and Comanche Indians, who were leaving the sanctuary of their agency near Fort Sill to raid white settlements and wagon trains across the border in Texas. It was all part of a long-standing game—albeit deadly serious at times—for the Indians, but Sherman did not find it amusing. Upon his arrival at Fort Sill, he demanded to see the principal Kiowa chiefs and hear their version of events.

Satana’s Unrepentant Admission

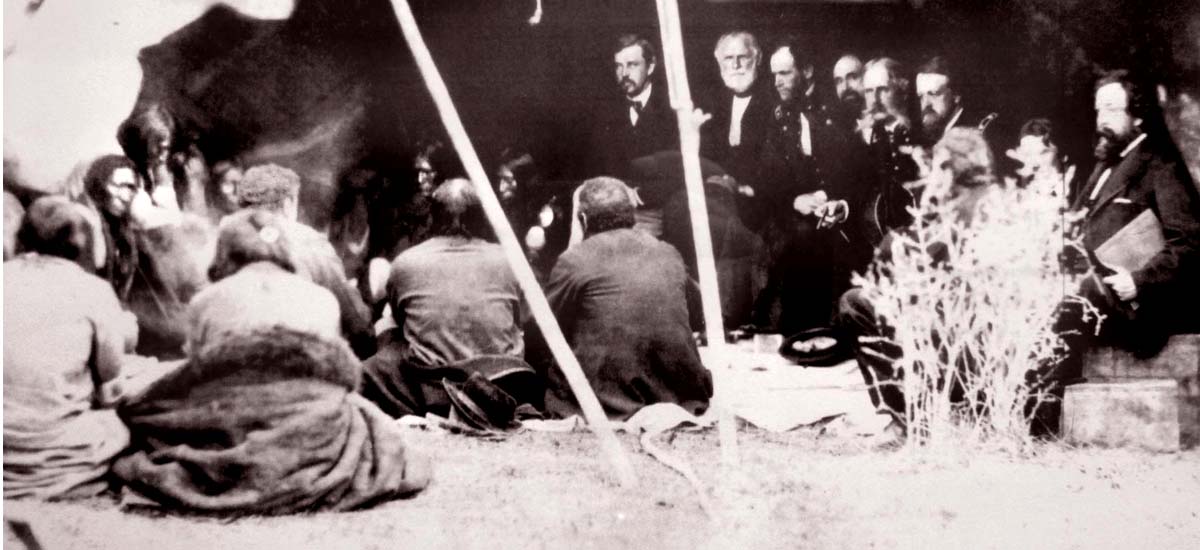

Chiefs Satanta, Big Tree, Satank, and Chief Lone Wolf rode into Fort Sill on May 27 to confer with the distinctly unamused Sherman and, not coincidentally, to draw more free government rations of sugar, coffee, and beef for themselves and their tribe. Satanta, the leader of the delegation, considered himself a diplomat as well as a warrior. He once had praised George Armstrong Custer, in all sincerity, as a “heap big nice sonabitch.” Now he turned his diplomatic skills on the scowling Sherman, who met the Indians on the front porch of Grierson’s headquarters.

Complaining bitterly (and not without some justice) of Army mistreatment of his tribe, Satanta freely admitted that he had personally led the most recent Texas raid on Lone Star teamsters near Jacksboro, which had resulted in the deaths of seven drivers and the theft of 41 mules. He was notably unrepentant. “If any other Indian claims the honor of leading that party,” said Satanta, “he will be lying to you. I led it myself.” Even worse, from Sherman’s point of view, the chief boldly asserted that Army control of the Kiowas was “played out now. There is never to be any more Kiowa Indians arrested.”

Saved from Certain Death

Sherman unsurprisingly disagreed, underlining his frank difference of opinion by ordering the immediate arrest of Satanta, Big Tree, and Satank. Satanta, throwing off the blanket he was wearing, grabbed for a pistol. The others followed his lead. Sherman, having anticipated the move, shouted an order and the shutters on the porch windows flew open, revealing several soldiers from the 10th Cavalry, their carbines aimed steadily at the Indians. “Don’t shoot, don’t shoot!” Satanta cried.

At that moment another Kiowa chief, Lone Wolf, came riding up, a bow and arrow in one hand, a Winchester rifle in the other. He took a seat on the porch, handing the bow to a tribesman named Stumbling Bear but keeping the cocked Winchester on his lap. Stumbling Bear, perhaps misinterpreting Lone Wolf’s intentions, suddenly drew back the bow and aimed an arrow at Sherman. Another Indian hit his elbow, deflecting the shot. Lone Wolf leveled his rifle at the startled general, but before he could fire, Grierson alertly jumped onto the chief, knocking him to the floor.

The Indians were led away in chains and Sherman was left with yet another reason to value the quick-thinking, quick-acting Hoosier cavalryman, who had saved him that day from certain death.

Not only was Grierson a former music teacher, but he actually did not like horses.

The highpoint of his ACW career (and what ‘made’ him as an officer) was his diversionary raid into Mississippi while Grant was working his way into the state from across the river.

And what “made” Grierson’s Raid successful was the less-known raid by Abel Streight, who pulled N.B.Forrest out of Mississippi to chase him into Alabama. Take that away and Grierson has to deal with Forrest. They met several times in 1864 and Grierson got the worst of it each time.

What times were those in 1864 that Grierson met Forrest and “got the worst of it?”

Hoosier??? Grierson was born in PA, and was from Jacksonville, IL, enlisted in the 6th IL Cavalry at the beginning of the war. He’s buried in Jacksonville. Also, this account differs from Wilber Nye “Carbine and Lance: The History of Old Fort Sill”. I’d go with Nye, it’s seen as the definitive history on Fort Sill.