By Blaine Taylor

Despite being ridiculed as a vain, pompous, and glory-seeking imbecile in a spate of biographies, diaries, letters, trial transcripts, and memoirs by leaders, field marshals, generals, and diplomats from both the Allies and his own Axis partners during and after the war, Joachim von Ribbentrop nevertheless was one of the premier foreign affairs practitioners of the Nazi epoch.

In his life full of ironies, he was one of the first of the top Nazi German leaders to have a full-scale biography done on him, in 1943, This Man Ribbentrop—His Life and Times, by Dr. Paul Schwarz, a disgruntled former foreign office official who had served with him in Berlin. His autobiography, The Ribbentrop Memoirs, written between August 25 and September 23, 1946, in his Nuremberg jail cell as he awaited hanging as a convicted war criminal, appeared with added material from his widow in 1954 and is the only account of his remarkable life in his own words.

From that date until 1992, as virtually every other top Nazi leader was profiled in a seemingly unending series of biographies, von Ribbentrop, whom Adolf Hitler called his “second Bismarck” because of his many foreign affairs successes, remained virgin territory to book authors. That changed, however, with the appearance that year of two excellent biographies, Hitler’s Diplomat: The Life and Times of Joachim von Ribbentrop, by the late John Weitz, and Ribbentrop by Michael Bloch, reissued in 2003 in a paperback edition, thus making it more generally available to would-be readers.

Many writers have wondered why Hitler ever picked von Ribbentrop as the Third Reich’s second foreign minister on February 4, 1938, in a move that stunned even Ribbentrop. His contemporaries, particularly his rivals for power and influence within the Nazi Party and German Reich government, who were legion in number, also wondered. Part of the answer was that he was well traveled, far more than almost anyone else in the top leadership cadre, especially the Führer himself, having journeyed to London, Rome, Paris, and New York before his appointment, and to Moscow afterward. He had not visited Tokyo, although during the war he wanted to get there either by long-range Luftwaffe aircraft or by U-boat, but such travel was forbidden by Hitler as too dangerous.

His rivals both within and without the Third Reich had ample reason to be jealous of von Ribbentrop, moreover, because of the number of positions he held in succession and the signal diplomatic success he achieved while in them.

These included being head of the Nazi Party’s Ribbentrop Bureau outside the regular foreign ministry during 1934-1938, Special Commissioner for Disarmament Questions during 1934-1935, during which post he managed to have signed the landmark Anglo-German naval treaty on June 18, 1935, something no one thought he could accomplish; ambassador to Great Britain from 1936 to 1938, and Reich foreign minister from 1938 to 1945.

In this final posting, von Ribbentrop negotiated and signed the most important treaty of the entire prewar period, the Nazi-Soviet Non-Aggression Pact of August 1939, which gave the green light to the joint German-Russian invasion of Poland and helped launch World War II. In 1946, he insisted it was his “very own idea,” not Hitler’s. Taken together or viewed singly, these were no mean feats, indeed, for any diplomat of any regime in any era.

In addition to those, he also negotiated the Anti-Comintern (Communist International) Pact of 1936 that brought Imperial Japan into the German orbit for the first time; the Axis Pact with Fascist Italy on May 22, 1939; and the final coup de grace, the Tripartite Pact of September 27, 1940, which tied into one alliance Germany, Italy, and Japan and was designed to keep the United States out of World War II. Due to the Japanese attack at Pearl Harbor, however (which surprised not only Hitler and von Ribbentrop but also Japan’s ambassador to Berlin), the last goal failed.

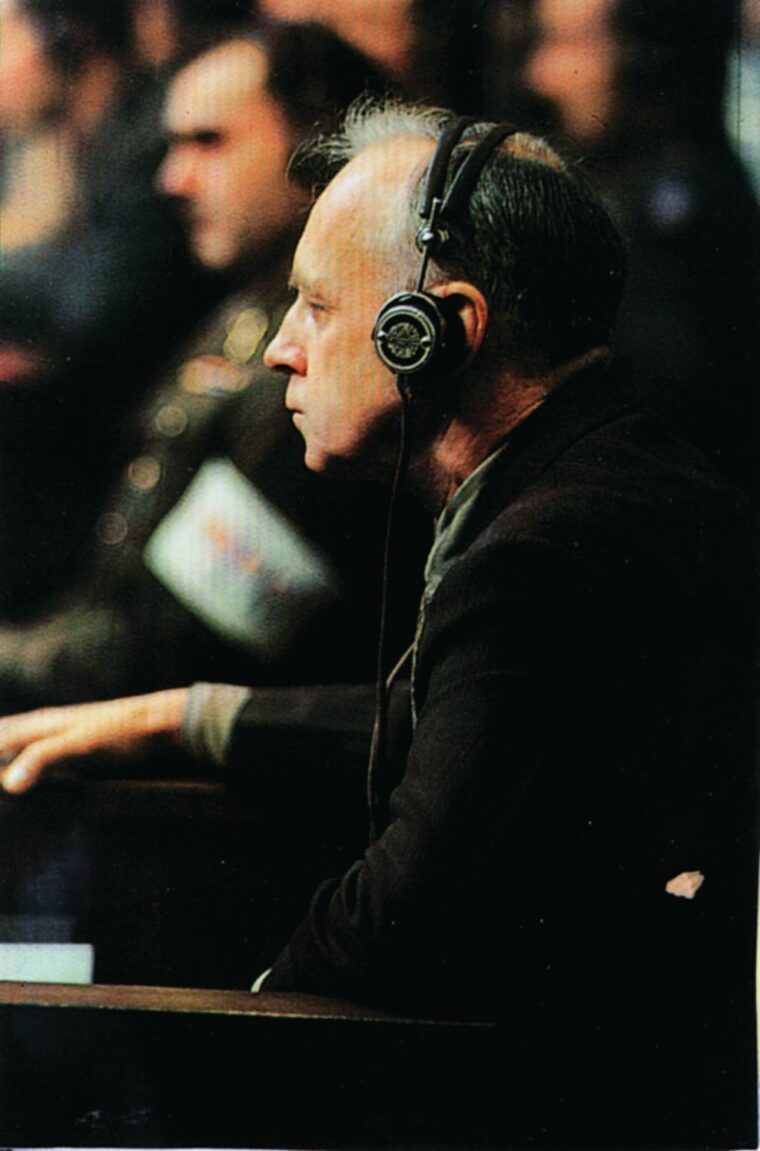

At least in part for all of these treaties, von Ribbentrop was convicted and hanged by the international military tribunal at Nuremberg on October 16, 1946, at age 54. He was then the number one offender following the suicide that same night of former Reichsmarshal Hermann Göring, his major rival.

Joachim von Ribbentrop was born at Wesel on the Rhine River on April 30, 1893. The offspring of several generations of soldiers, he became interested in foreign affairs when he chanced to see Kaiser Wilhelm II and King Edward VII of England during the latter’s state visit to imperial Germany in 1909.

Before spending the years 1910-1914 in Canada, young Ribbentrop (the title of von was purchased later from a relative) made his first trip to London. He always felt an affinity for the might, main, majesty, and power of the British Empire, he asserted, even in prison. He considered it an extreme irony of his life that he was viewed by both Allies and Axis as having hated Britain. This sentiment, he believed, was assumed by others to be so strong that he advised Hitler wrongly that Britain would not fight in 1939 to prevent further German territorial aggrandizement. This he denied vehemently in his memoirs.

While in Canada, he worked for 18 months as a bank clerk at Montreal, was a bridge construction worker in Quebec despite having had surgery to remove a kidney, spent several months in New York City, and was even a reporter there. This experience reflected the fact that he spoke English and French fluently, another reason Hitler picked him in 1938 as Reich foreign minister. Indeed, he even translated briefly for the Führer before a full-time translator was hired.

“I seriously considered being a violinist,” he later recalled wistfully; and he also rode horses, hunted, played tennis, skied, and bobsledded during the 18 months he lived in Switzerland during his youth.

When World War I broke out in August 1914, von Ribbentrop thought it his patriotic duty to return home from Canada for military service but lamented in his jail-cell memoirs later, “What if I had stayed?” Certainly he would not have been facing the hangman’s rope. When his ship was stopped at sea, the ever resourceful future diplomat hid in a coal bunker and then talked his way out of wartime internment as an enemy alien.

Back home, he avoided a medical examination and thus joined the Blue Hussars at Torgau, where in 1945 the Red Army would effect its famous juncture with the Americans. Unlike all the other top Nazis, von Ribbentrop saw combat action on fronts both east and west and was duly awarded the Iron Cross 1st Class for valor under fire. He proudly noted in his memoirs that four generations of his family had received the coveted medal, including his son Rudolf, a Waffen SS panzer officer on the Eastern Front in World War II.

During service in Turkey, Germany’s World War I ally, he met Franz von Papen, who later served as a Weimar Republican chancellor and worked with Göring and von Ribbentrop to make Hitler Reich chancellor on January 30, 1933. Indeed, some of these all-important secret negotiations took place in the von Ribbentrop family home at Dahlem, a posh Berlin suburb. The end of World War I and the unexpected defeat of Germany had come as a complete shock to von Ribbentrop. “We officers considered it especially humiliating that our epaulettes should be replaced by blue stripes,” he later noted.

Working at the War Ministry in the immediate postwar period, 1st Lieutenant von Ribbentrop helped the Army prepare for the upcoming Versailles Peace Conference that both he and Hitler later did so much to dismantle during 1933-1938. In 1919, he resigned his Army commission after five years and joined the Berlin branch of an old Bremen firm of cotton importers, in which he could put his considerable foreign contacts to good use.

“The owners soon granted me power of attorney,” he remembered proudly, and his success was crowned on July 5, 1920, by the fortuitous marriage to Annelies Henkell, the wealthy heiress of a still well known, prosperous German wine and champagne firm. She was destined to survive both World War II and her marriage to von Ribbentrop. Disputing the allegation by Nazi Propaganda Minister Dr. Josef Goebbels that von Ribbentrop “married his money,” his widow wrote in 1954: “In 1924 my husband gave up the Henkell agency and devoted all his time to the importing firm, which he alone had developed, and of which he was the sole owner.”

Like Göring and Rudolf Hess, von Ribbentrop was a devoted husband and family man, writing to his wife in his farewell note the day before he was hanged, “I again touch your dear head and look deep into your eyes with all the unending love which one human being can have for another.” Despite this, in January 1945, he offered to fly to Moscow with his entire family as hostages, to meet again with Josef Stalin in an attempt to end the war, but his Führer refused.

He met Hitler at Berchtesgaden on August 13, 1932, and immediately joined the Nazi Party as a result, taking his place within the inner ranks of those working with von Papen to have Hitler named German chancellor, his first such great service that the Führer never forgot.

Far from being the yes man that his enemies called him, Hitler himself termed von Ribbentrop “his most difficult subordinate.” This was mainly because he asserted that he constantly tried to moderate the Nazis’ stand against the Jews, both for humanity’s sake, he wrote, and because it made Germany look bad in the eyes of world public opinion. He also tried to end the war with Soviet Russia, especially after the twin defeats of Stalingrad and Kursk in 1943, when it became clear that the Third Reich would lose.

During what he called the “critical years of 1935-36,” von Ribbentrop sought in vain, he claimed, for personal meetings between the new Reich chancellor and the top leaders of France and England. These duly occurred in September 1938 at Munich, but by then the chances for alliances with both had gone for good. The Führer, like Göring later, even wanted to fly to London himself in 1936. In the end, Hitler sent von Ribbentrop as the new German ambassador to the Court of St. James’s upon the death of the previous representative.

“Ribbentrop, bring me the English alliance!” Hitler commanded as he saw him off, but his mission failed because, he testified, the British would not allow Germany to become too powerful on the continent of Europe, and thus upset what they called “the balance of power.” This echoed the United Kingdom’s stance since the days of French King Louis XIV.

Von Ribbentrop wrote in a 1938 secret memo from London, “England is our greatest enemy,” after talking with both Winston Churchill and the man he considered the Third Reich’s greatest foe, Sir Robert Vansittart, permanent under-secretary in the British Foreign Office.

“He [Hitler] did nothing but offer England friendship,” complained von Ribbentrop, adding that the Führer even into 1940 offered to “guarantee” the British Empire with a force of 12 German divisions if asked in return for a free hand for German expansion in the East and the return of one or two former imperial colonies for raw materials. The offer was continuously rejected, however.

In 1936, von Ribbentrop asserted that he vigorously opposed sending Luftwaffe planes and pilots to aid Generalissimo Francisco Franco in the Spanish Civil War, but Hitler and Göring prevailed. In 1943, he also tried to arrange a personal Hitler-Stalin summit conference to end the war in the East, but the Führer demurred because he believed that a military victory must be won first. It never was.

Hitler sometimes seemed to act as his own foreign minister and appeared not to trust his Foreign Office. In addition, von Ribbentrop faced the rivals who wanted his job at home: Göring, Goebbels, Nazi theologist Alfred Rosenberg, and Reichsführer SS Heinrich Himmler among them. The latter even tried to involve him in a scheme to replace Hitler, to which he claimed he replied, “Himmler, I will not play this game. I remain loyal to the Führer.”

As for the Army and assassination plots against Hitler, von Ribbentrop stated in 1946, “I never entered into a conspiracy and remained loyal to the end.” In fact, he was loyal beyond the end of the Third Reich, as his defense before the tribunal at Nuremberg proved. He refused to assert disloyalty to the dead Führer even when fighting for his own life during testimony on the witness stand.

His basic defense stance was that neither he nor Hitler wanted war in 1939, only the settlement of the Polish question, in which they felt Britain really had no interest. Ribbentrop also stated that neither he nor Hitler believed the British would go to war over Poland.

“I was never informed about military questions,” he avowed, and swore he did not know of the plan to attack the Soviet Union until April 1941, two months before it occurred. Still, he asserted that he argued against it right up to the day of the invasion.

Von Ribbentrop was in favor of a Japanese attack on British-held Singapore but wanted at all costs to keep the United States out of the war, he insisted. Like all the other 21 defendants in the dock at Nuremberg, he felt that it was an “enemy court” that was illegal and biased against all of them, only interested in seeking convictions and death sentences, not justice. In short, he believed it was “victor’s justice,” as Göring had also claimed.

“Not even half of my evidence was admitted…. Only the prosecution, not the defense, had access to German and foreign archives,” he wrote, maintaining to the last that neither he nor Hitler sought “world domination.” Instead, he said, the Führer wanted Stalin’s westward expansionism into Central Europe contained. Ribbentrop wrote his memoirs, and his defense was largely conducted from von Ribbentrop’s memory alone.

On October 15, 1946, Joachim wrote to Annelies, “I am perfectly composed and will hold my head high whatever happens … proud and unbroken, and in the firm belief in an eternal life, I shall go on my way.” Even his harshest critics have admitted that he mounted the steps of the gallows with courage, there to meet his fate.

Towson, Maryland, freelancer Blaine Taylor is the author of six books on the World War II era, the most recent being Hitler’s Headquarters from Beer Hall to Bunker, 1920-1945.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments