By Kirk A. Freeman

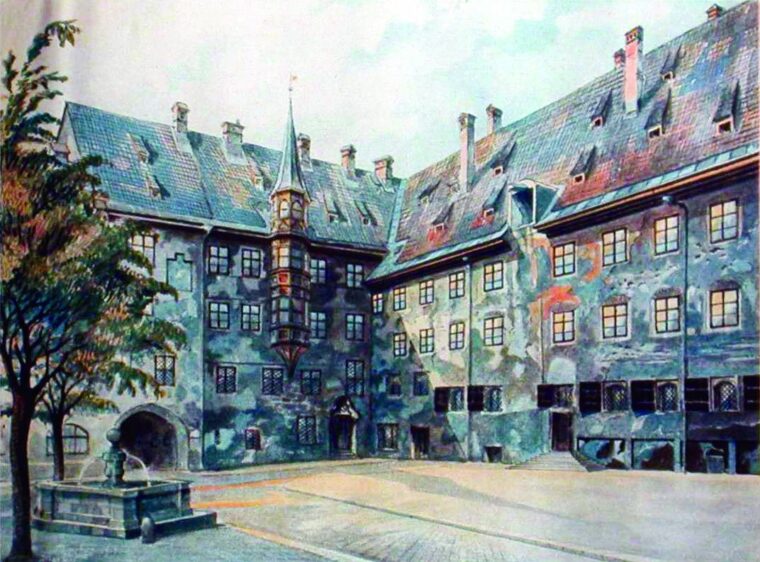

In the months before the outbreak of World War I, 25-year-old Adolf Hitler was living the starving artist’s life in the Bavarian city of Munich, selling his paintings door-to-door and in the city’s numerous beer halls. Hitler had fled to Munich from Vienna in 1913 to avoid being drafted into the Austrian Army, which he felt allowed too many mixed bloods and different cultures into the ranks. Austrian authorities caught up with him six months before the start of the war and forced him to take a physical exam to see if he was fit to serve. Ironically, Hitler was deemed “too weak for armed or auxiliary service, unfit to bear arms.”

Hitler Enlists for the First World War

Hitler learned of the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand when his landlady, Frau Popp, burst into his room in hysterics and shouted, “The Austrian heir to the throne has just been murdered!” According to Hitler, he dropped to his knees and thanked heaven for letting him be there during a time when Germany would be fighting to save itself. He then rushed out into the street to blend into the quickly gathering crowd in the Odeonsplatz. A photograph taken at the time shows a jubilant, sallow-faced Hitler in the crowd celebrating the coming war. Hitler’s life of loneliness and insignificance was about to end.

Hitler tried to enlist in the 1st Bavarian Infantry on August 5, but he was sent away because the Army had more volunteers than it needed. A fortnight later he was summoned to report to Recruiting Depot VI in Munich and enlisted as private No. 148 in the 1st Company, 16th Bavarian Reserve Infantry Regiment. Also enlisted in the regiment was Lieutenant Rudolf Hess, later to become deputy führer of Nazi Germany, and Sgt. Maj. Max Amann, later in charge of the Nazi press.

Between August 16 and October 8, Hitler and his comrades were stationed at Oberweisenfeld Barracks for training in weapons and marching. A comrade named Hans Mend later wrote that when Hitler was issued his rifle “he looked at it with delight, as a woman looks at her jewelry, which made me laugh.” The regiment had heart and spunk, but not much more. Lieutenant Fritz Weidemann, a professional soldier, noted that the regimental commander had not been on active service in years and that most of the company commanders were former reservists without any combat experience. Weidemann also noted that the training was quick and inadequate, that the regiment had few machine guns, and that none of the soldiers had an iron helmet; instead they wore oilcloth caps in 19th-century Napoleonic style.

On October 9, the regiment marched out of Munich for the trip to Camp Lechfeld, 70 miles to the west. In full combat gear, the men marched in a continuous rain for 11 hours. In a letter to Frau Popp, Hitler reported that his company was put up in a barn for the night, but that no one could sleep because they were soaked through and shivering from the cold. Late the next day the regiment arrived at its destination. On October 21, the regiment boarded railcars for transport to the front. The men sang “The Watch on the Rhine” and broke into cheers when they finally saw the great river—the first time that most of them (including Hitler) had ever seen the Rhine.

The next day the men disembarked from the train and, after reorganizing, marched to Lille, Belgium, which had been recaptured by the Germans from the British. On the 23rd, the regiment marched through the desolate town. Hitler became nervous when British shells began to land, since the town was full of ammunition carts and soldiers. The shelling did not last long, and the men bedded down on the wet and cold flagstones of the town’s streets.

Hitler’s First Battle: The Battle of Ypres

On October 25, at 3 am, the regiment entered its first battle, arriving just in time to join the German assault during the first phase of the Battle of Ypres. The regiment’s objective was to take a farmhouse and the edge of the woods beyond the house, about half a mile from the German lines. A heavy fog had risen, forcing a delay in the attack timetable while others rounded up the lost battalions. At dawn the attack began, but a few steps out the regiment came under intense fire from the right. In the fog and confusion, the regimental hats that Weidemann had complained about brought trouble. A regiment of Württemburg troops on the regiment’s right thought the Bavarians were British and opened fire, inflicting heavy casualities. Hitler and his friend Ernst Schmidt threw their caps away instantly and ran to the rear headquarters to report the situation and stop the slaughter. The first hour the regiment spent in combat, it lost many valuable men, including the regimental commander, to friendly fire.

After this incident the attack proper began, with the British dropping artillery shells into the assaulting columns. The men crawled into shallow dugouts and shell holes to escape the flying shrapnel, before racing to a small farmhouse in the middle of the field and crawling into a ditch. During this assault, Hitler’s platoon leader was killed, as were most of the noncommissioned officers. In all, it took five bloody assaults to take the edge of the forest. The final assault ended in hand-to-hand combat, and Hitler was surprised when he jumped into the British trench and made a soft landing—he had landed on a British corpse.

A Decorated Soldier

This was the only battle in which Hitler fought as a true frontline soldier. For his bravery and soldierly conduct, the new regimental commander, Lt. Col. Philipp Engelhardt, recommended Hitler as a dispatch runner (Meldegänger) to serve at regimental headquarters. Someone also recommended Hitler and Schmidt for the Iron Cross, although neither received the decoration. Of the 3,600 men who marched out of camp with the regiment, 373 men were killed in the first three weeks of fighting. Hitler’s uncanny luck began in his first battle. At one point, a shell exploded near him; it killed another soldier, but Hitler only had a sleeve ripped away.

On November 3, Hitler and his friends Ernst Schmidt and Ignaz Westenkirchner were officially assigned as dispatch runners (eight runners were needed per regiment). This was not a cushy job but a highly dangerous responsibility. Early in the war, dispatch runners traveled in pairs, armed only with pistols and carrying a leather wallet attached to their belts marked XXX for urgent, XX for quick, and X for “in your own time.” A runner ran hunched forward through trenches and dived into shell holes, then sprang up between artillery salvos and sprinted to the next trench, all the while hoping he had properly calculated the timing between shells. On Hitler’s first run during the Battle of Messines, six miles southwest of Ypres, three runners were killed and one wounded of the eight on staff. On the second day, the regimental commander was wounded near Hitler and Schmidt; under heavy fire, Hitler and Westenkirchner carried their wounded commander to an aid station. Hitler was promoted to corporal for bravery.

A few days later, Engelhardt went to inspect the British position and took Hitler and Hitler’s friend Balthasar Brandymayer with him. At the edge of a wood, Engelhardt stepped out to see the British trenches better and instantly drew fire. Hitler and Brandymayer stepped in front to protect Englehardt from harm, before dragging their commander to a nearby ditch. The next day, Hitler and several others were called to headquarters and told that they had been recommended for the Iron Cross. It was Hitler’s second nomination in two months. When four more company commanders arrived, Hitler and the others left to give the officers room. Five minutes later a British shell hit the tent, killing most of the men inside and severely wounding Engelhardt.

On December 2, Hitler was decorated with the Iron Cross 2nd Class. Later, he called it “the happiest day of my life.” His self-esteem had received its first real boost. The regiment was pulled back from the front for rest and refitting just after Christmas. It was during this pause that men began to notice Hitler’s eccentric behavior. During lulls in combat, he was either reading philosophical works or sketching and painting with a box of watercolors he always carried. Hitler was considered odd because he never drank, smoked, or showed any interest in women. When others talked of the French women, Hitler would leave the group in disgust. If he saw a soldier flirting with a French woman, he would reprimand the soldier for hours about the sins of the flesh. At the same time, comrades noted Hitler for being kind to enemy captives and civilians, even attending funeral services for downed enemy airmen to pay his respects.

Life in the Regiment

Hitler rarely received mail or wrote any letters himself. During a lull in the fighting and for refitting from the front in late 1914, Hitler received a parcel filled with treats and breads from a baker he knew in Munich. He quickly wrote the baker to thank him, but instructed him never to write him again. When comrades asked Hitler about his home, his response was always the same, that the regiment was his home.

On February 11, 1915, Hitler was sitting in a dugout when an enemy shell struck. Several men were killed and wounded, but Hitler escaped with only a small scratch to his face. This was the third time that Hitler’s luck held for him. Hitler’s only true friend was a small dog that had wandered in from the English side and fell into the German trenches. Hitler named the dog “Foxy,” and for the next few years it was his closest companion.

In March, the regiment was sent into the trenches near Fromelles, France, to defend a two-mile trench line against the British and French. In May, the Allies launched an attack and the Germans counterattacked. Hitler was in the thick of the fighting. He took on extra duties that put him near the front, close enough that he personally captured three French prisoners by July. The extra duties took their toll on Hitler, but he never shirked from danger. When the British broke through the lines one day, Hitler was the only volunteer to take a message to the front. No one expected to see him alive again, and everyone was surprised when he returned with a message from the frontline command. Once again, Hitler’s uncanny luck held out. He was eating with some men in a dugout when he heard a voice telling him to move to another dugout. Five minutes later a shell exploded in the dugout, killing everyone in it.

The regiment remained near Fromelles for most of 1916 and was involved in the spring and summer offensives. In July, Hitler dragged a fellow runner back to the trenches during a heavy artillery barrage. On September 27, the regiment was pulled out of the lines in Flanders and sent to the Somme. The area was a living hell. At 5 am on October 5, Hitler was caught out in the open under a British rolling barrage and severely wounded in the thigh by shrapnel. He lay there for hours until a few comrades went to find him and brought him in.

Forming Hitler’s Hatred

Hitler begged Lieutenant Fritz Weidemann to let him stay with the regiment, but by the 9th, Hitler was on a hospital train back to Germany. This was the first time he had been away from the front in two years, and the civilian world shocked him. When Hitler was being removed from the train to an aid station, the first thing he heard was a German woman’s voice. This astounded him—he had not heard a German-speaking woman in two years. When aid workers placed Hitler on clean sheets, he was afraid of getting them dirty and had trouble sleeping in a bed after so many months at the front.

It was during this time that Hitler began developing an irrational hatred of anything he saw as “impure.” When he toured Berlin, he was appalled at the grumbling and griping of the civilians and noted—so he claimed—that “every clerk was a Jew and every Jew a clerk.” He accused the Jews of shirking from duty. This was untrue. Statistically speaking, the percentage of Jewish soldiers in the German Army was nearly the same as the percentage of Aryans, with the same casualty rates.

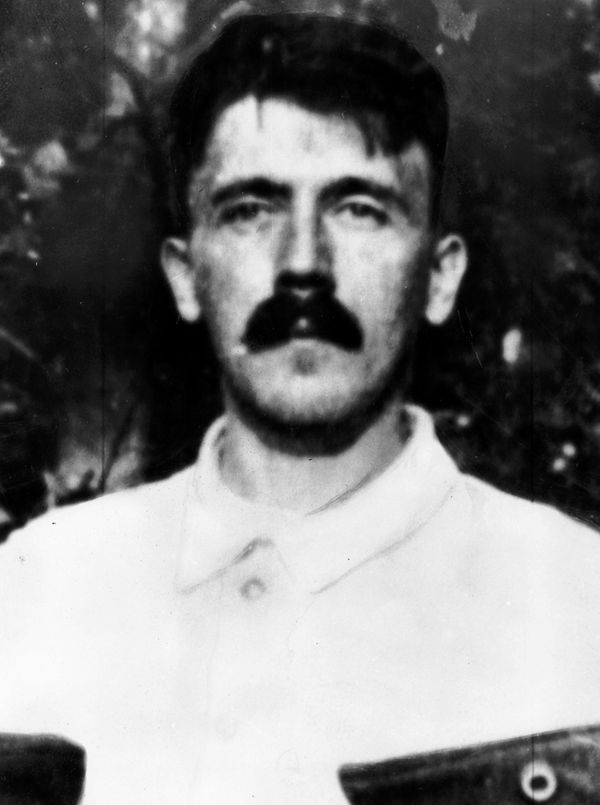

After he had recovered enough to walk, Hitler was assigned light duty in the 2nd Bavarian Infantry Regiment. It was there that Hitler grew his distinctive moustache, which was popular among English soldiers. Hitler wrote continuously to Weidemann, begging for his help to get back to the front. Weidemann came through in March 1917, and Hitler gladly returned to the regiment. When Hitler returned, Foxy began to jump around excitedly. Hitler was in great spirits; a few soldiers even saw him laughing while playing with the dog. That night Hitler, armed with a flashlight and bayonet, was heard stabbing rats late into the night until someone chucked a boot at him.

On March 4, the regiment returned to the front lines a few miles north of Vimy. Heavy rains had turned the shell holes into deep ponds and quagmires of mud that could suck a man under. In the trenches, soldiers forced their way through mud and cold water that rose past their knees. At the beginning of June, the regiment was sent to Flanders to help repulse a British offensive near Ypres.

In August, the regiment was pulled from the line and sent to Alsace to regroup. On the train ride, a French railroad official offered Hitler 200 marks for his dog. Hitler refused, saying that the dog was worth more to him than 200,000 marks. When he got off the train, Hitler could not find Foxy and began to hunt everywhere for his pet. He never found him. While he was hunting, someone pilfered his knapsack and stole his painting supplies and sketchbook. Hitler never painted again. Of the missing Foxy, he wrote later, “The swine who took him from me doesn’t know what he did to me.”

An increasingly distraught Hitler began to show some of the psychopathic qualities that people would attribute to him later. Up to then, he had never said anything negative about the Jews to his comrades, but now he began to make increasingly inflammatory remarks. To tease him, the men would bemoan the war and gleefully watch Hitler fume about how the Germans could not afford to lose. In September, Hitler was decorated a second time with the Cross of Merit 3rd Class with Swords for valorous service. At the end of September, he took an 18-day leave and went to Berlin, staying with a comrade’s parents. According to his postcards, he enjoyed the sights and hoped to return to Berlin after the war.

In March 1918, the Germans launched their last great offensive of the war and morale was high. Hitler’s regiment took part in the Second Battle of the Marne and sustained heavy losses; this action went on until Allied counterattacks halted the German offensive after 800,000 German casualties in four months. During this time, Hitler overheard a new recruit spewing derogatory statements. He confronted the recruit and a vicious fistfight broke out, with Hitler emerging victorious.

In July, while running a dispatch, Hitler came upon the commander of 9th Company, who had been wounded by an American shell. He half carried, half dragged the officer to the rear. Later that month, the regiment’s 1st Battalion suffered under an intense bombardment and was raked by heavy machine-gun fire. The battalion had advanced so far that their own artillery was shelling their position. The battalion commander, Hugo Gutmann, promised Hitler the Iron Cross 1st Class if he could get a message to the artillery to quit shelling the forward positions. Hitler miraculously made it through and Gutmann kept his word. In later years, Hitler maintained that he had personally captured 10 French prisoners to win the decoration, a transparent attempt to hide the fact that he gotten his medal upon the recommendation of a Jewish officer.

On August 4, 1918, Hitler received the Iron Cross 1st Class, a decoration that few nonofficers ever received. This was the last decoration that Hitler received during the war. Nine days later, near La Montagne, the regiment was hit hard by a chlorine gas attack that seeped into many of the men’s gas masks. Hitler was blinded by the gas and stumbled back in a “blind-line” in which each man held onto the coat of the man in front of him as they walked single-file to the rear. While Hitler lay in the hospital recovering, a local minister came into the ward on November 10 to announce that the war was ending the next day at 11 am. The Kaiser, he said, had fled Germany. Hitler was so shocked that he buried his head in a pillow and went into psychosomatic blindness for a week.

The Man He Became

Throughout the rest of his life, Hitler remained proud of his military record and mentioned it frequently. He would not tolerate any opinion that might smudge his military career or personal image (real or imagined). When former comrade Hans Mend published an unflattering eyewitness accounts about Hitler in World War I (including a homosexual affair that Hitler allegedly had with another soldier), Mend quickly disappeared into a “reeducation” camp in 1938, never to be heard from again. Other former comrades did not talk about the Hitler they had known in World War I.

During World War I, Hitler rose from an insignificant, unknown, struggling artist to a decorated, angry veteran. During 45 months and 36 major battles, he developed the personality characteristics that later haunted the world. His regiment suffered 3,754 casualties, including several of Hitler’s friends. There is no record of Hitler ever killing a man in combat. He was more frequently remembered as a nice chap, one who wrote poetry, read, sketched, and painted in his off hours. Serving in the army gave Hitler a self-confidence he never had before. Using his newfound self-assurance, he began to rally his countrymen with the blind rage and hatred that propelled Germany and the rest of the world toward the darkest days of the 20th century. It all began with Hitler’s grueling experiences in World War I.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments