By Patrick J. Chaisson

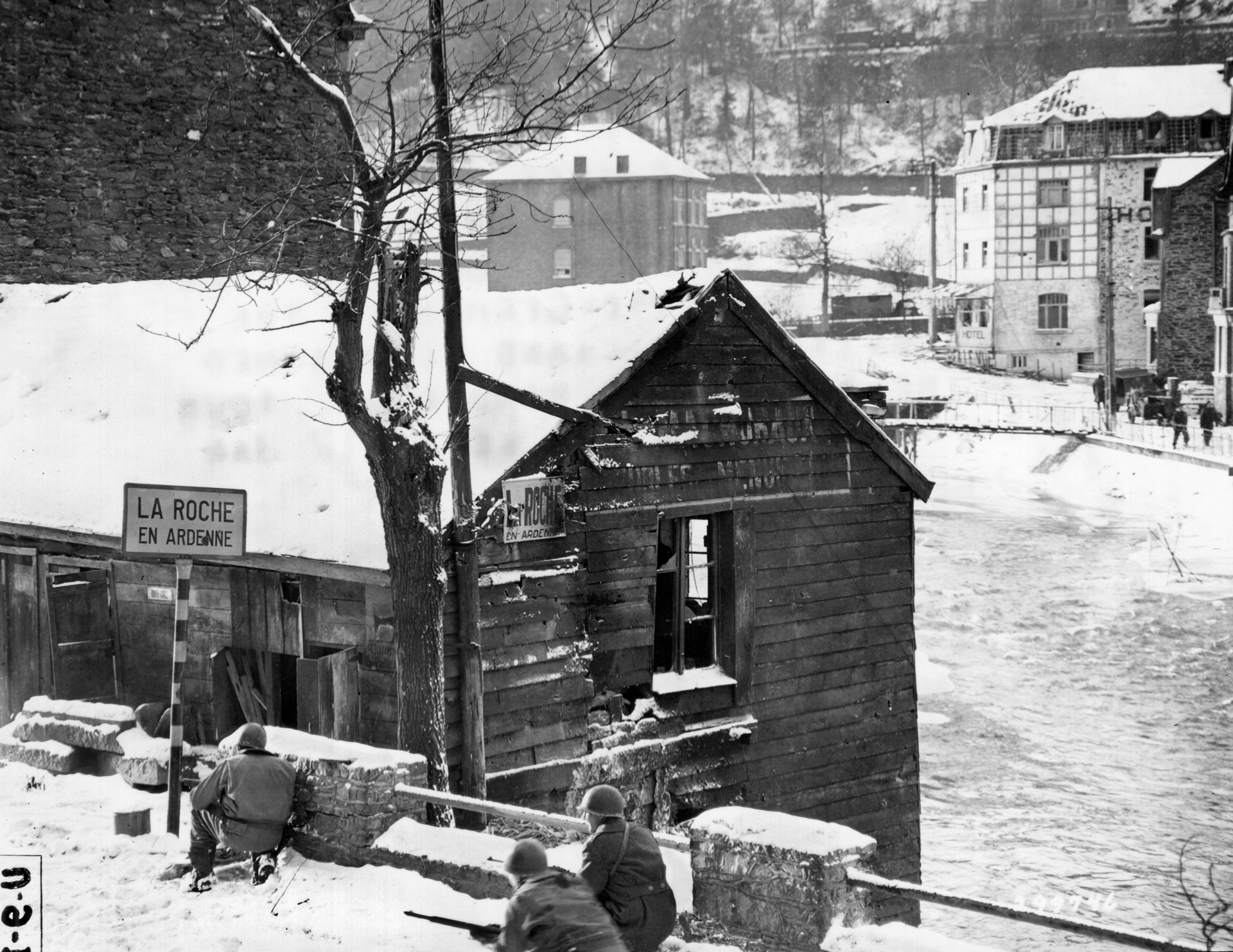

Warsaw was burning. Captain Jack Van Eyssen first saw it as a dull glow on the night horizon, 35 miles distant. Van Eyssen, a pilot with South African Air Force (SAAF) Squadron 31, nosed his Consolidated Liberator bomber into a dive and told the six other crewmen aboard to get ready. They were about to enter an inferno.

“Rows upon rows of buildings were on fire and sent palls of smoke thousands of feet into the air,” Van Eyssen recalled years later. “The smoke was in turn illuminated from below by the fires. Obviously, a life or death struggle was taking place before us.”

Leveling off at 150 feet, Van Eyssen flew north along the silvery Vistula River while bomb-aimer Sergeant Herbert Hudson counted bridges. After the third one, Hudson uttered a sharp command and Van Eyssen banked his Liberator hard left onto its final approach. With flaps extended and throttles cut, the massive bomber slowed to 130 miles per hour as it neared Warsaw’s Krasinski Square.

Just then, Van Eyssen’s warplane became caught in the glare of a dozen German searchlights. Gusts of 20mm antiaircraft shells ripped through its aluminum skin, destroying both engines on the right wing. Seconds later, relentless gunfire set alight a third engine.

Hudson jettisoned the aircraft’s payload of 12 cargo canisters while Van Eyssen and his co-pilot desperately attempted evasive maneuvers. They succeeded—somehow the stricken bomber held together as it sluggishly climbed to an altitude of 1,000 feet. Now over Soviet-controlled territory, Captain Van Eyssen and three other crewmen managed to bail out of the doomed Liberator. Everyone else—including Sergeant Hudson—perished along with their airplane.

The loss of Jack Van Eyssen’s Liberator VI (equivalent to a B-24J in American service) during the early morning hours of August 15, 1944, was but one small act in a heroic but ultimately futile drama of World War II. The story of the Warsaw Airlift was one of treachery, raw courage, and defiance in the face of impossible odds. It also highlighted several ugly realities brought on by political interference in tactical matters. At its center was a Royal Air Force (RAF) officer who night after night ordered his men to fly into a maelstrom from which he knew many would not return.

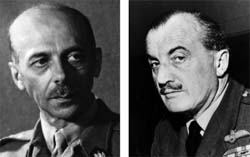

From his headquarters in Caserta, Italy, Air Marshal John Slessor followed with considerable interest the Red Army’s inexorable advance across Poland. Soviet forces had by July 1944 reached the outskirts of Warsaw, while Russian radio broadcasts encouraged patriotic Poles to rise up against their Nazi oppressors. The time was ripe for insurrection, but no one then could imagine how quickly events in the prewar Polish capital were to unfold.

As commander in chief of RAF Mediterranean and Middle East (MEDME), the 47-year-old Slessor controlled a number of special operations air squadrons whose task was to supply resistance forces across German-held Greece, the Balkans, and Poland. One of these outfits was Polish Special Duties Flight No. 1586, with a total of seven aircrew on hand as of August 1. Flight 1586 operated a mix of Handley-Page Halifax and Consolidated Liberator bombers, parachuting weapons, matériel, and secret agents into Poland whenever weather conditions permitted.

Special Duties Flight No. 1586 was one of several Polish outfits trained and equipped by the RAF following Poland’s fall in 1939. Although subject to the King’s Regulations and subordinate to British air commanders, these Poles nevertheless proved themselves to be an aggressive, independent-minded lot. They rapidly earned a reputation for bravery bordering on recklessness.

Complicating matters, Free Polish commanders were never entirely free from the influence of their London-based government in exile. A considerable number of military leaders, diplomats, and elected officials had also escaped to Great Britain, eventually setting up an expatriate administrative apparatus for the war’s duration. Secretive, obstinate, and fiercely focused on the liberation of their native soil, the exiled Polish War Ministry frequently issued direct orders to its units in combat with little regard for the proper chain of command.

While relations with their British allies were often strained, these Free Poles harbored outright hatred for the Soviet state and its despotic ruler, Josef Stalin. As the Red Army approached Warsaw in mid-summer 1944, it became abundantly clear to Stanisław Mikołajczyk, Polish prime minister in exile, that the Moscow regime had no intention of sharing power with his London-based government. A more dramatic measure would be necessary to gain Stalin’s attention.

There existed in occupied Poland an underground resistance organization known as the Armia Krajowa (AK, or Home Army), led by Lt. Gen. Tadeusz Komorowski. Known by his code name, Bór (forest), this former Polish Army officer commanded an estimated 45,000 irregulars in the Warsaw region. At 1700 hours on August 1, 1944, under orders from the London government in exile, Bór launched Operation Burza (Tempest), the Warsaw Uprising.

Those responsible for initiating this insurrection hoped to stage a fait accompli. By seizing Warsaw, Bór’s Home Army intended to present advancing Soviet armies with Poland’s former capital city under the control of a force loyal to Prime Minister Mikołajczyk’s government. From this position of strength, Free Polish leaders figured, a more equitable postwar future for their people could be assured.

They could not have figured more wrongly. Once the uprising commenced, Red Army reconnaissance troops (who could see Warsaw from their positions across the Vistula) were withdrawn 12 miles south, conveniently just beyond the range of Russian artillery. And though the Soviets enjoyed near-total air superiority, all overflights of AK-held territory abruptly ceased.

Stalin claimed these measures were merely a tactical response to Nazi counterattacks occurring elsewhere. In reality, he was more than happy to sit back and watch the Germans and Free Poles slaughter one another over control of Warsaw. Red Army commanders also prohibited British or American aircraft from entering Soviet-controlled airspace in order to resupply Polish insurgents.

Nevertheless, Bór-Komorowski’s ill-equipped Home Army had in one day managed to liberate three-quarters of Warsaw. To keep it, though, the AK needed help. For this assistance Poland’s government in exile turned to its oldest ally, the United Kingdom.

The first Polish demands for aid were both considerable and impossible to provide. They first requested that Allied bomber command in Europe immediately shift its focus away from strategic targets in favor of tactical ones that supported the uprising. Additionally, Poland’s exiled leadership wanted its airborne brigade dropped on airfields near Warsaw to hold them for use by four squadrons of Polish-flown North American P-51 Mustang fighters. And all this had to happen in a matter of days, despite the fact that Warsaw remained well beyond the combat radius of any Allied aircraft operating from England.

The Poles also asked for significantly increased air delivery of machine guns, ammunition, anti-tank weapons, and grenades. This was the one appeal that British Prime Minister Winston Churchill felt he could realistically fulfill; accordingly, he directed his military chiefs of staff to investigate its feasibility. The only Allied special operations bombers with the range to reach Warsaw and return fell under Air Marshal Slessor’s MEDME Command, so he was in the best position to evaluate such a mission’s operational feasibility. On August 3, Slessor received an urgent cable from the Air Staff wanting to know whether it could be done.

He replied the next morning: “Air supply to Warsaw … not a practical proposition.” Uncertain weather and a full moon meant exposing flight crews to many hazards en route, while alert antiaircraft defenses were certain to claim more bombers over the target. Few cargo canisters, Slessor predicted, would ever make it into the hands of AK fighters. In summary, he reluctantly concluded, “We should achieve practically nothing and lose a high proportion of our special duty aircraft” in an operation that would do little to affect the ultimate fate of Poland’s underground army.

While Air Marshal Slessor believed an air bridge to Warsaw would certainly fail, there were others under his command who were more than ready to give it a try. As it turned out, all seven flight crews from Polish Special Duties Flight No. 1586 were scheduled to fly an aerial resupply sortie to other parts of their homeland that very evening. Would the fearless but willful airmen of No. 1586 Flight follow those orders or instead go to the aid of their countrymen then battling the Germans?

At the Poles’ mission briefing that afternoon, British staff officers repeated Slessor’s instructions to avoid Warsaw. They could not know, however, that General Bór-Komorowski had earlier sent a wire directly to Flight 1586’s commander, Major Eugeniusz Arciuszkiewicz, requesting his crews carry out airdrops to the city’s defenders. It was a request the loyal Polish aviator could not turn down.

“Who’d like to go to Warsaw?” Arciuszkie-wicz asked his men once the RAF briefers departed. The assembled aviators roared with approval; to a man they all volunteered for the flight. It was decided that four experienced crews would fly to Bór’s strongholds while the remaining three were to carry out their original assignment “for appearance’s sake.”

Each bomber making the journey to Warsaw carried up to 12 waterproof metal containers as payload. A typical canister measured 8.2 feet long with a diameter of three feet. It weighed 350 pounds and could be filled with Sten submachine guns, PIAT antitank launchers, 9mm ammunition (used by both British- and German-made small arms), and medical supplies. Dropped from the aircraft’s bomb bay, these cylinders employed drogue parachutes to slow their descent but required a low, slow approach to ensure an accurate delivery.

The straight-line distance between Flight 1586’s base at Brindisi and Warsaw was 815 miles. However, air mission planners had to plot detours around known enemy flak concentrations and night fighter bases, which made for a nearly 2,000-mile round trip. Other hazards included ice and lightning storms, violent wind shear, and blinding fog. Due to short summer nights, Allied bombers would have to take off and land in broad daylight as part of a typical 11-hour journey.

Special Duties Flight No. 1586’s three Liberators and one Halifax destined for Warsaw struggled into the air at 2100 hours on Sunday, August 4, 1944. Dangerously overloaded, the war-weary planes slowly made their way across Yugoslavia and over the forbidding Carpathian Mountains. Flying in loose “bomber stream” formation, each individual aircraft commander had to manage his own navigation and air defense.

Warrant Officer Jan Cholewa vividly described his Liberator’s approach to the flashlight-marked Jewish Cemetery. “Below us we can see Warsaw’s first buildings and containers going to the ground as well as a Halifax turning right. I slow down, lower the landing gear and the flaps, and open the bomb doors; we’re going at the speed of 130 miles [per hour]. The cemetery is now in front of us.”

Cholewa’s account continued: “‘Drop it!’ I can hear the navigator shout, and at the same moment the machine bops up. ‘The containers are gone,’ says the navigator. Emilio [the co-pilot] retracts the landing gear and the flaps, we speed up. ‘A few packages have landed on the street,’ yells the tail gunner.”

Three of the four Polish special operations bombers reaching Warsaw that night delivered their payloads to Home Army forces near the city center. Though airmen described antiaircraft fire over the target as “light,” a Liberator flown by Flight Lieutenant Jan Mioduchowski lost an engine to flak over Krasinski Square. His plane was also shot up by a German night fighter while returning home, crash landing at Brindisi without injury to the crew.

Lost to history is Air Marshal Slessor’s reaction upon learning No. 1586 Flight disobeyed his orders to stay away from Warsaw. Likely he suspected the Poles would go there with or without his permission. Besides, Slessor had bigger problems to face. Five of seven RAF special-duty bombers dispatched to objectives elsewhere in Poland that previous evening had failed to return.

In response, Slessor immediately canceled all flights to Polish drop zones. He believed Bór’s Home Army, absent Soviet assistance, could only hold out for a few more days no matter what the Western Allies did to aid it. Yet the AK’s resilience surprised him, as did what the air marshal termed a “crescendo of political pressure” brought on by outraged Polish authorities in London.

High-ranking officials within the government in exile fumed over John Slessor’s cancellation order. Their vitriol soon reached the ears of senior RAF commanders, prompting Air Chief Marshal Charles Portal on August 5 to cable MEDME Command. Portal did not direct Slessor to resume Poland-bound airdrops, but in his telegram the chief of the Air Staff suggested a “token gesture” might provide psychological support to Warsaw’s resistance fighters.

Meanwhile, Major Arciuszkiewicz’s aviators impatiently endured day after day of enforced inactivity while their countrymen in Warsaw fought and died. Finally, on August 7, Air Marshal Slessor felt he could no longer stand in their way. He authorized No. 1586 Flight to resume air delivery missions to the beleaguered city commencing the next evening.

On August 8, three Polish crews flew to Warsaw, followed one night later by four more successful drops. All bombers returned safely, leading Slessor to cable Portal that “[a] few aircraft on a show like this will sometimes get away with it.” This statement opened the door to a significantly increased Allied presence over Warsaw at the same time a deadly ring of German flak batteries began to close itself around the partisan-controlled city.

Air Marshal Slessor traveled on August 11 to Naples, where Winston Churchill was meeting with senior Allied commanders in the Mediterranean. There he explained to the British prime minister why resupply flights to the Polish city remained tactically unsound. Churchill, however, said the missions “must go on if only to boost the morale of the inhabitants of Warsaw.”

“You of course are correct from the military point of view,” Churchill added, “but from the political aspect you must carry on.”

It was a bitter pill for Slessor to swallow. He knew many of his flight crews, along with their hard-to-replace warplanes, would be lost in an expanded airdrop campaign. Yet to meet Bór-Komorowski’s supply requirement of 90 tons per night, more bombers were needed.

Aside from the Poles, Slessor had available one RAF special operations outfit trained for this type of work. The Halifax-equipped No. 148 Squadron, veterans of many clandestine operations across the Mediterranean, Greece, and Yugoslavia, sent six planes to Poland on the night of August 12 along with five No. 1586 Flight bombers. Seven aircraft successfully delivered cargo canisters to the Home Army, with one RAF Halifax downed by a German interceptor.

Early on August 13, the Foggia-based RAF No. 205 Group received an alert for special duty over Poland. Its newly assigned commander, South African Brigadier J.T. “Jimmy” Durrant, was not pleased with this assignment. His No. 178 (RAF) and No. 31 (SAAF) Squadrons had been busy for weeks bombing targets in support of Operation Dragoon, the invasion of southern France. Aerial resupply was a new game for these aviators, and an unappealing one at that. To many of them, flying a Liberator at rooftop level at near-stall speed into the teeth of enemy flak seemed like an act of sheer insanity. Orders were orders, though, and starting at 1930 hours 24 crews belonging to 148 RAF, 178 RAF, and 31 SAAF took off for drop zones in Warsaw. Two Liberators and two Halifaxes from No. 1586 Flight also went up that evening.

The Germans were ready for them. Sergeant Henry Lloyd-Lyne, an air gunner with No. 178 Squadron, recalled the ferocity of their assault. “At about the second bridge the antiaircraft fire was really intensive … and I could see that the outer port engine was on fire. It wasn’t long before the port inner was on fire as well. The whole wing looked to be on fire and the most amazing thing was that at this particular time the antiaircraft shells were coming through the bottom of the aircraft and going out through the top. I likened them then and I still do to cricket balls that were on fire. They looked about the size of a cricket ball and they were glowing. The 20mm stuff, I would have thought, I could virtually have put my hand out and caught them.”

After somehow dropping its payload onto Krasinski Square, the Liberator crashed into a wooded area. Of seven men aboard, Lloyd-Lyne emerged as the sole survivor.

Two SAAF flight crews also failed to return from that raid. One plane, commanded by Lieutenant Robert Randolf Klette of No. 31 Squadron, had a rough time just getting to Warsaw. Klette remembers crossing the Carpathians and “plunging into a brute of a cumulonimbus, vicious turbulence rocking, swinging and bumping the Liberator. It was like riding in a rodeo, the compasses spinning in all directions.”

Matters worsened for Bob Klette’s crew after German flak gunners caught their warplane in a vicious crossfire on its final approach. With three engines aflame, the mortally wounded Liberator staggered along at 100 feet over Warsaw as it headed toward an open area. This was the city’s abandoned airport, and miraculously Klette brought his bomber down alongside its main runway.

“Had we crashed? Was I dead and in heaven?” the dazed Klette remembered thinking afterward. He then realized the aircraft had made a perfect belly landing. “My God,” Klette exclaimed, “we’re alive!” His entire crew survived the crash, but one man was killed while trying to evade capture. The rest surrendered to an enemy patrol.

Those Polish partisans struggling to hold their city against an ever-tightening German stranglehold reacted with joy to the Allies’ increased aerial presence. On August 14, Bór-Komorowski radioed, “The gallant effort of your airmen has enabled us to continue our struggle. Fighting Warsaw thanks [these] heroic airmen and sends her highest appreciation. We bow with deepest reverence before fallen crews.”

This was small comfort to Jimmy Durrant, whose No. 205 Group had just lost 21 men and three bombers on a mission he deemed utterly useless. That morning the young aviator visited Slessor’s headquarters in Caserta to lodge a formal protest but was made to wait for some time while his boss sat in conference behind closed doors. When Air Marshal Slessor emerged, Durrant immediately confronted him with an impassioned plea to halt all supply drops. Slessor listened patiently, then invited the brigadier inside his office. Seated there was Winston Churchill.

After receiving permission to speak, Durrant recounted 205 Group’s losses over the previous evening. He then suggested the Allies were throwing away invaluable aircraft and trained flight crews over Poland for no military value. In response, Churchill said he understood the group commander’s position but insisted that all possible aid must be given to Warsaw’s insurgents. Jimmy Durrant’s men would go up again that very evening.

For this sortie, Nos. 178 and 31 Squadrons mustered 15 Liberators, many of them hastily repaired after the previous night’s mission. No. 148 Squadron put up another six Halifax bombers, while the Polish No. 1586 Flight contributed two Liberators and three Halifaxes.

With German fighters, searchlight teams, and antiaircraft batteries now on full alert, the operation quickly devolved into a bloodbath. Captain Roman Chmiel of 1586 Flight claimed his aircrew could smell Warsaw burning from the flight deck of their Halifax, “the ground and the sky mingling in one blinding eruption of flame.”

Into that vast furnace, remembered Chmiel, “a South African Liberator came skimming over the chimney-stacks, firing with all its guns. It shot out some of the searchlights, but then the pilot, probably dazzled, crashed into a church steeple.” Chmiel’s own aircraft made several passes over the ruined city before his navigator recognized their drop zone and released 12 canisters over Krasinski Square.

In the raid’s aftermath, Slessor cabled London: “Last night’s operations to Warsaw, 26 [sic] dispatched, 11 successful. 8 missing including 6 Liberators of 205 Group. One of 148 Squadron and one Pole. Group have lost 25% of their strength in two nights.”

John Slessor knew the Allies could not pay this price in men and machines much longer. Morale among his flight crews began to crumble; even the stoic Poles were having difficulty coping with the nightly loss of friends and compatriots over Warsaw. The South Africans of 31 Squadron had been especially hard hit. Slessor took them off the flying schedule for 24 hours to allow for crew rest and badly needed maintenance to be performed on their battle-damaged Liberators.

Now back in London, Winston Churchill sent a series of urgent appeals to his American and Soviet allies. The United States Army Air Forces (USAAF) possessed a barometric parachute release that enabled bombers flying at high altitude to deliver resupply containers with some degree of accuracy. Yet without Soviet landing rights in place, British-based B-17 Flying Fortresses still could not reach Warsaw. And Churchill’s repeated pleas to obtain those rights were all met at the Kremlin with stony silence.

On August 15, six bombers (three each from 178 and 148 Squadrons) headed for drop zones in the Kampinos Forest, 12 miles west of Warsaw. Two turned back early with mechanical trouble, leaving four planes to complete their task before returning safely. This marked the beginning of a more cautious phase in the airlift, with flight crews avoiding central Warsaw’s flak-infested cauldron in favor of supplying AK strongholds outside the city.

The next raid went badly for Air Marshal Slessor’s special duty aircraft. On August 16, six 31 Squadron Liberators, another three from 178 Squadron, and four Halifaxes from 148 Squadron joined five Polish warplanes bound for targets in the Kampinos Forest. German and Hungarian interceptors savaged the bomber stream, downing four planes that night.

Since the start of the Warsaw Airlift on August 4, Polish Special Duties Flight 1586 and No. 178 Squadron had each lost four Liberators, No. 148 Squadron two Halifaxes, and No. 31 Squadron eight Liberators, for a total loss of 18 aircraft. The South African squadron, now down to two flyable bombers, was taken off operational status to rebuild its combat strength.

Air Marshal Slessor had seen enough. Once more canceling all future Warsaw missions, he bluntly informed Prime Minister Churchill that unless supplies could be sent from England or Russia the Home Army was simply “beyond our help.” And yet again, political pressure from exiled Polish officials compelled him to allow the battered No. 1586 Flight to resume its dangerous nighttime forays into the heart of burning Warsaw.

Only an extended period of bad weather spared these courageous aviators from certain disaster. Also, by the end of the month replacement bombers and aircrews had arrived in Italy to bolster Flight 1586’s thin ranks. From August 20 to 28, the unit went out 38 times to Warsaw and other Polish cities, losing four bombers in the process. Another three aircraft went missing on the stormy night of September 1 while delivering cargo canisters to resistance forces.

In a month of relentless fighting, General Bór-Komorowski’s Home Army had improbably held out against eight German combat divisions and SS “police troops.” Now those courageous Poles began to believe they had been forsaken by their oldest allies. One communiqué, transmitted on September 1 (the fifth anniversary of World War II’s outbreak), read, “The people of Warsaw are left to their own devices, abandoned on the front of the common fight against the Germans.” Yet Slessor’s flight crews could do nothing to aid them until the weather improved.

Two matters of significance took place on September 10. First, the Soviets finally allowed Allied bombers flying aerial resupply missions over Warsaw access to their landing fields. Second, the arrival of barometric parachute releases in Italy enabled Air Marshal Slessor to schedule an RAF-led airlift sortie that night. Fifteen bombers—including three Liberators from the recently arrived No. 34 (SAAF) Squadron—participated, releasing their payloads from an altitude of 11,500 feet while flying within Soviet-controlled airspace as much as possible. Three Polish, one RAF, and one SAAF aircraft were shot down in this raid.

Another two flights from Italy, flown on September 18 and 20, delivered a smattering of supplies with no loss to Slessor’s aircrews. By now the Western Allies were sharing Warsaw’s skies with Soviet biplanes, also dropping weapons and ammunition to AK enclaves. Few of these Russian-built munitions, released without parachutes, made it undamaged into the hands of Home Army insurgents.

The final note of this aerial concerto was at once its most majestic and plaintive. At 1200 hours on September 18, a total of 107 B-17s of the USAAF Eighth Air Force escorted by 64 Mustang fighter aircraft appeared high over Warsaw. Bór’s partisans watched with amazement as the bombers disgorged 1,284 containers, most of which landed on German-controlled territory. Polish combatants managed to recover a paltry 288 canisters dropped that afternoon.

The end came at 0800 hours on October 2, 1944, when General Komorowski and the remnants of his Armia Krajowa surrendered. They had fought at great cost for 63 days, as demonstrated by the loss of an estimated 15,000 of the AK’s 45,000-member force. More than 150,000 Polish civilians also died in the uprising, after which all surviving residents were forcibly expelled from their homes. When Red Army forces finally entered the derelict city in January 1945, they found it almost completely destroyed.

For his part, Air Marshal John Slessor viewed the airlift as “a story of the utmost gallantry and self-sacrifice on the part of our air crews, RAF, South African and above all Polish.” A total of 31 Allied warplanes were lost in the campaign, along with some 200 aviators captured, killed, or listed as missing in action. Slessor later calculated that one aircraft was destroyed for every ton of supplies delivered. Perhaps the Warsaw Airlift’s greatest tragedy was the loss of so many Allied airmen on a politically motivated mission that in the end had no realistic chance of success.

Patrick J. Chaisson is a retired U.S. Army officer and historian who writes from his home in Scotia, New York.