By Mark Carlson

The morning of June 23, 1916, dawned over the broad crenellated valley of the Meuse River in northeastern France. The weather was warm with breezes coming down from the north, but they did not carry the scent of wildflowers or grapevines. Instead, the soldiers of 3 Company of the French 137th Infantry Regiment smelled only death on the wind. The stink of expended cordite, scorched wood, and rotten corpses permeated the air around them. Their trench, wreathed in barbed wire and surrounded by shell craters was in a salient a short distance from what had once been the most heavily fortified bastion in France, Fort Douaumont. That stronghold was now in German hands. Two battalions of the 137th had been ordered to hold their lines against the German Fifth Army.

But there was little doubt that the soldiers, clad in the characteristic horizon blue jackets and trousers, helmets, and leather belts with ammo pouches, had no illusions about their ability to hold off a determined German infantry assault, especially those that carried flamethrowers and grenades. Yet there was no talk of retreat or surrender. These were French soldiers, sworn to defend their sacred homeland to the death against the vile Boche. They would fight every German who showed his pointed helmet to the 137th Infantry. They had reliable Lebel 8mm rifles tipped with 20-inch bayonets, and they knew how to use them.

The real worry was artillery. The Frenchmen all knew what concentrated heavy guns could do to an entrenched position. They were very exposed on high ground, well within sight of German artillery in the woods east of the Meuse River. Ordered into the hastily dug trenches on June 10, the officers tried to place their companies to minimize the effects of a direct hit. Only God and luck would play a part in survival or slaughter.

Shortly after sunrise a series of deep booms, like distant thunder rumbled over the quiet valley. Then several dozen sharp bangs split the air. The Germans were beginning their prefatory bombardment, just as they had done in February when they had hammered the French positions with nearly a million shells. The ground around the huddled soldiers shook with dozens, then hundreds, then thousands of detonations. Towering fountains of dirt and flame erupted into the sky, turning the air into a haze of brown and gray dust and smoke. Every blast seemed to be right on top of them. The explosions split their world with stunning noise that made their ears ring.

There was no point in trying to see what was happening, and certainly it would be useless to shoot back with rifles. All they could do was wait and pray. Every day, deadly barrages fell on the French. More valiant defenders were blasted and shredded in an instant. They held their ground and waited.

By that time, the French battalions had been under fire for two solid weeks. It was obvious the Germans were determined to kill them all. Whole stretches of the trench were immolated by successive concussions. Direct hits by mortars collapsed the trench walls and killed and maimed scores in an instant. But worse was to come for the men of 3 Company. Of the original 164 men, only 73 were still alive on the morning of June 23.

Then it happened. They had been huddled down behind the forward wall, facing east. Their rifles were ready, leaning up against the trench wall and fire step. They heard the whining moan of another falling mortar coming in. Instinctively every man ducked, but it was too late. Fate had dealt 3 Company’s shell-shocked survivors a deadly hand.

The huge German mortar, designed to destroy concrete dugouts, exploded at the edge of the trench in a titanic detonation that must have been like a lightning strike. Every single man died where he stood. The walls of the trench crumbled and fell in, entombing them. When the smoke cleared, only the bayonets remained out of the soil.

This was typical of Verdun, the longest and bloodiest single campaign of the Great War. Unlike the rapidly shifting lines of World War II, the Western Front between France and Germany centered on the great river valleys of the Somme and Marne. Following the Schlieffen Plan, the Germans invaded Belgium on August 4, 1914, and fought their way into northeastern France towards Paris. But a determined and desperate counteroffensive by British and French troops held the Germans along the Marne River. Their lines remained in that location. Miles of trenches, dugouts, listening posts, communication lines, and artillery batteries grew ever more complex as the months passed with little ground gained or lost by either side.

The war then entered a long and terrible phase in which artillery barrages and doomed infantry attacks did little more than fill graveyards across Europe. German Kaiser Wilhelm II berated his generals, demanding that they explain to him the reason his troops were not already in Paris.

The Battle of Verdun was conceived by the aristocratic German Chief of the General Staff Erich von Falkenhayn. By early 1916 Britain’s army consisted of 70 fully armed, albeit hastily trained, divisions under arms. The French had 96 divisions, with more being trained and deployed each month. Each infantry division numbered 7,000 troops, including artillery batteries. The British Expeditionary Forces were crossing the English Channel in ever greater numbers.

With Germany already fighting on two fronts, Falkenhayn had few reserves. Realizing that Germany would soon lose the advantage, he devised an audacious plan to destroy the French army as a fighting force. Once this was achieved, Germany could throw its entire effort on the Western Front toward the British.

“Britain’s continental partners should be destroyed,” Falkenhayn wrote in a December 25, 1915, letter to the Kaiser. Although Italy was of no real consequence, Russia was a constant drain on German forces. An attack on Russia would result in the same debacle that Napoleon had faced in 1812. Falkenhayn was certain that while Russia’s internal political unrest would cause Tsar Nicholas II to sue for peace, France was another matter.

“The strain on France has reached breaking point,” he continued. “If we succeed in opening the eyes of her people, that in a military sense, they have nothing to hope for, that breaking point would be reached. England’s best sword would be knocked out of her hand.” In short, Falkenhayn was counting on the spirit of the French people to revolt and demand an end to the war. A major offensive directed at Verdun would, he wrote “compel the French command staff to throw in every man they have.”

The intent of the Verdun offensive was to break French morale. “The forces of France will bleed to death,” Falkenhayn told Kaiser Wilhelm, “whether we reach our goal or not.” The Kaiser concurred. “This war will end at Verdun,” he said confidently. The Germans called their Verdun offensive Operation Gericht, meaning place of judgment. It was a portentous name for a campaign of slaughter on an unimaginable scale.

What Falkenhayn did not know was that the Allied High Command had at the same time agreed on a massive drive on the German lines to take place in summer 1916. The plan, suggested by commander-in-chief of the French army, General Joseph Joffre, to Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig, the newly installed commander of the British forces, was to make a massive combined assault on the center of the Western Front. The two senior commanders agreed that the campaign would be in the Somme Valley.

The city and citadel of Verdun had a long history that stretched back to the time when the region was under Roman rule. Situated 80 miles from the German border to the northeast, Verdun endured a long and savage siege during the Franco-Prussian War that began in July 1870 and ended in a German victory in January 1871. Verdun had only surrendered after Paris had fallen. Spread around the historic citadel on the east bank in a deep loop of the Marne, Verdun was a small city of 20,000 people.

The French built a ring of forts to support Verdun and command the Meuse Valley. Fort Douaumont was the most heavily fortified position in the world at the time. Constructed between 1886 and 1913 at a cost of six million gold Francs, Douaumont had heavy stone and concrete walls 30-feet-thick to withstand the largest-caliber siege artillery. Virtually a self-contained underground city, Douaumont garrisoned 500 troops and dozens of long-range guns that dominated the area for a radius of 10 miles.

Five miles from the city center, Douaumont was the cornerstone of the ring of 18 forts including its smaller neighbors, Forts Vaux, Souville, and Tavanne. A complex maze of barbed wire, trenches, and mutually supporting machine-gun posts protected the fort from infantry assault. In the woods east of the Meuse River, more trenches, observation posts, dugouts, and machine guns lurked behind still more barbed wire. The French intended these fortified lines to act as a tripwire to warn the garrison of an impending German attack.

But after German siege artillery had reduced the Belgian fortress of Liege in August 1914 with amazing ease, Joffre concluded that such big and heavily armed emplacements were of no real value. Joffre ordered a sharp reduction in August 1915 of the number of troops garrisoning Fort Douaumont. Moreover, he recommended that 54 of the large-caliber batteries and more than 100,000 shells be removed to where they might be more effective. By February 1916 Verdun was defended by just one regular division, the 14th Division, two French reserve divisions, the 51st and 72nd, and the 37th Algerian Division.

The French 56th and 59th Chasseur Battalions had driven the Germans out of the Bois des Caures woods north of the city in 1914. Seventeen months later the French battalions still held that position. Their commander was a popular Member of Parliament, 61-year old Lt. Col. Emile Driant, who had repeatedly protested Joffre’s orders to weaken Verdun’s defenses.

Verdun had no real strategic value. There were no major rail lines or roads, no munitions factories or warehouses full of supplies. But to Falkenhayn, the city was worth every German life it took to reach it. He was adamant that his armies not capture the city itself, which would be of no use to him. He believed the threat to the sacred city would make the French throw themselves into repeated attacks against his lines. He calculated that five Frenchmen would die for every two Germans. If the defenders gave up, they would lose Verdun. If they remained to fight, the whole French army would be destroyed.

Falkenhayn assembled an initial force to supplement the 70,000-strong German Fifth Army commanded by 33-year-old Crown Prince Wilhelm, the Kaiser’s son. He received the cooperation of the German Air Service, which agreed to commit 138 fighters to rid the skies of French observation planes. He brought in 850 artillery pieces and an initial supply of 2.5 million shells for the first assault.

Fortunately for Falkenhayn, a rail line came to within 12 miles of the city. The superb German railroads were in constant operation, transporting 1,300 cars worth of troops, guns, shells, and supplies. Of the 542 heavy guns assembled for the offensive, 13 were 420mm howitzers and 17 were 355mm howitzer. These giant howitzers had pounded the Belgian forts into submission in 1914.

But even more than mortars, machine guns, and artillery, the chief of the general staff had raised the bar of cruelty with hand grenades, poison gas, and flame throwers. These weapons of barbarity were intended to kill as many French soldiers as possible.

The Germans constructed more than 100 concrete dugouts in the eastern woods of the Meuse Valley for the rapid emergence of their best assault troops. By this time their army consisted of veterans who had already endured countless battles. They were issued the new Stahlhelm, the now-familiar German helmet instead of the outdated pickelhaube. Made of heated steel, the Stahlhelm better protected the neck and head. The soldiers received specific instruction in how to use hand grenades effectively and how to breach barbed-wire defenses.

What Falkenhayn had assembled was a powerful army in which each mile of the French defensive line faced a full German division with 150 guns. “Not a single line is to be [left] unbombarded, no possibility of supply unmolested, nowhere should the enemy feel safe,” Falkenhayn decreed.

The one thing Falkenhayn could not control was the weather. The bombardment and assault had been scheduled for February 10. But in order to direct the critical artillery barrage, the observation balloons, tethered far behind German lines, needed clear skies to report the fall of artillery rounds on the French lines. Cold rain persisted until February 19. Falkenhayn waited one more day for a warm sun to dry out the mud.

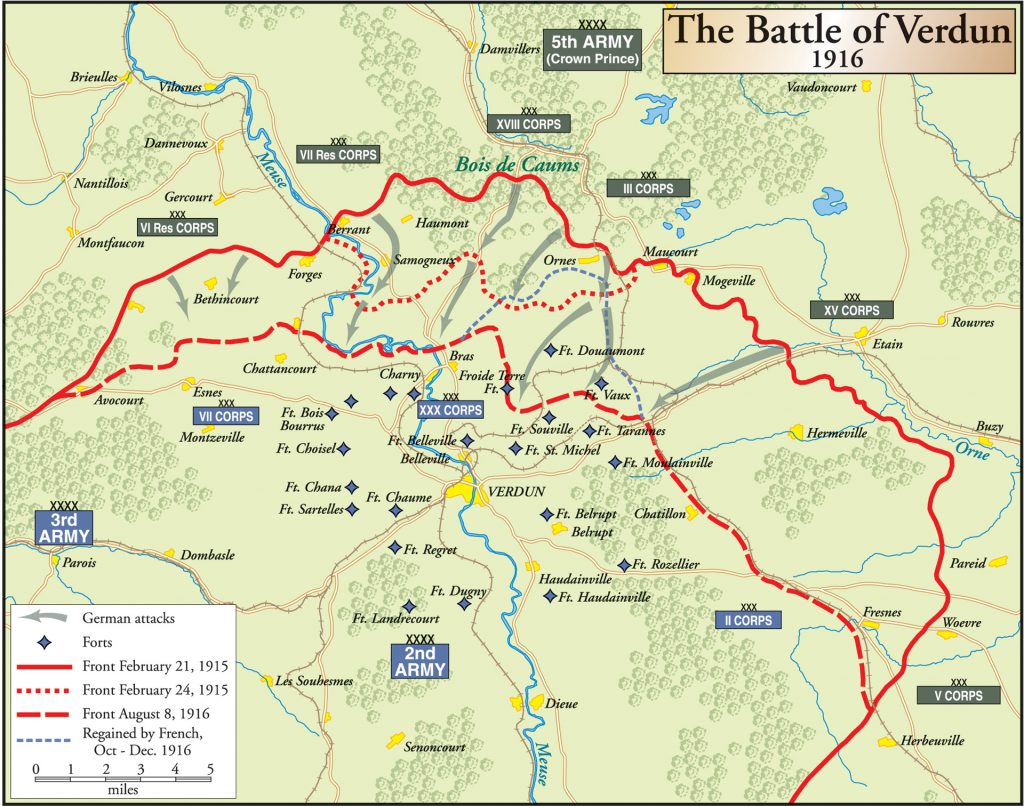

Joffre received intelligence that a major build-up of German forces was approaching Verdun, but he was unimpressed as there seemed to be no strategic objective. He was convinced it was a diversion. But he did move the VII and XXX Corps into the area. Verdun’s defenses had less than one-third of the strength of what was about to hit them.

On the morning of February 21, 1916, Falkenhayn had all of his chess pieces in place on the vast board that would become the battlefield of Verdun. Upon his order, the Germans unleashed their initial artillery barrage on the unsuspecting defenders. German guns and howitzers arrayed on an eight-mile front roared in one continuous orgasm of fire and fury. From the heavy bark of 5.9-inch heavy field howitzers to huge railway guns that hurled two-ton shells at the city, Falkenhayn watched his grand plan unfold.

The first salvoes slammed into the city’s cathedral, bridge, and railway station. The impact of the giant shells caused major damage. The stunned French defenders endured a constant barrage of shells that seemed to go on forever. Not a second went by without the scream of falling shells, the detonations of mortars, and whizzing shrapnel that laced the air with hot death. The stunned Frenchmen could only huddle in their dugouts and trenches. German mortar shells collapsed trench walls, burying entire battalions of French troops. The lucky ones who survived the ordeal were left stunned and deafened.

For nine solid hours, the rain of deadly explosives tore the defensive lines apart. Thousands of smoking craters marked the valley. The rain of artillery shells leveled entire villages. The shells reduced mature forests to a sea of splintered stumps and burning brush. Farmhouses and barns became blazing pyres of hay and dying animals. Shredded bodies of men and animals watered the once-fertile soil of the Meuse Valley with blood and gore.

In the forest known as the Bois des Caures, where Driant’s two battalions of Chasseurs hunkered down during that first day, an estimated 80,000 shells fell in an area 1,000 yards by 500 yards. It was like “peering into Dante’s Hell,” recalled a German pilot flying who flew over the area afterwards. Even though nearly a million shells had been fired, Falkenhayn’ plan to totally destroy the French lines before the infantry attack did not come to fruition. As bad as it had been, some French units survived to meet the German attack.

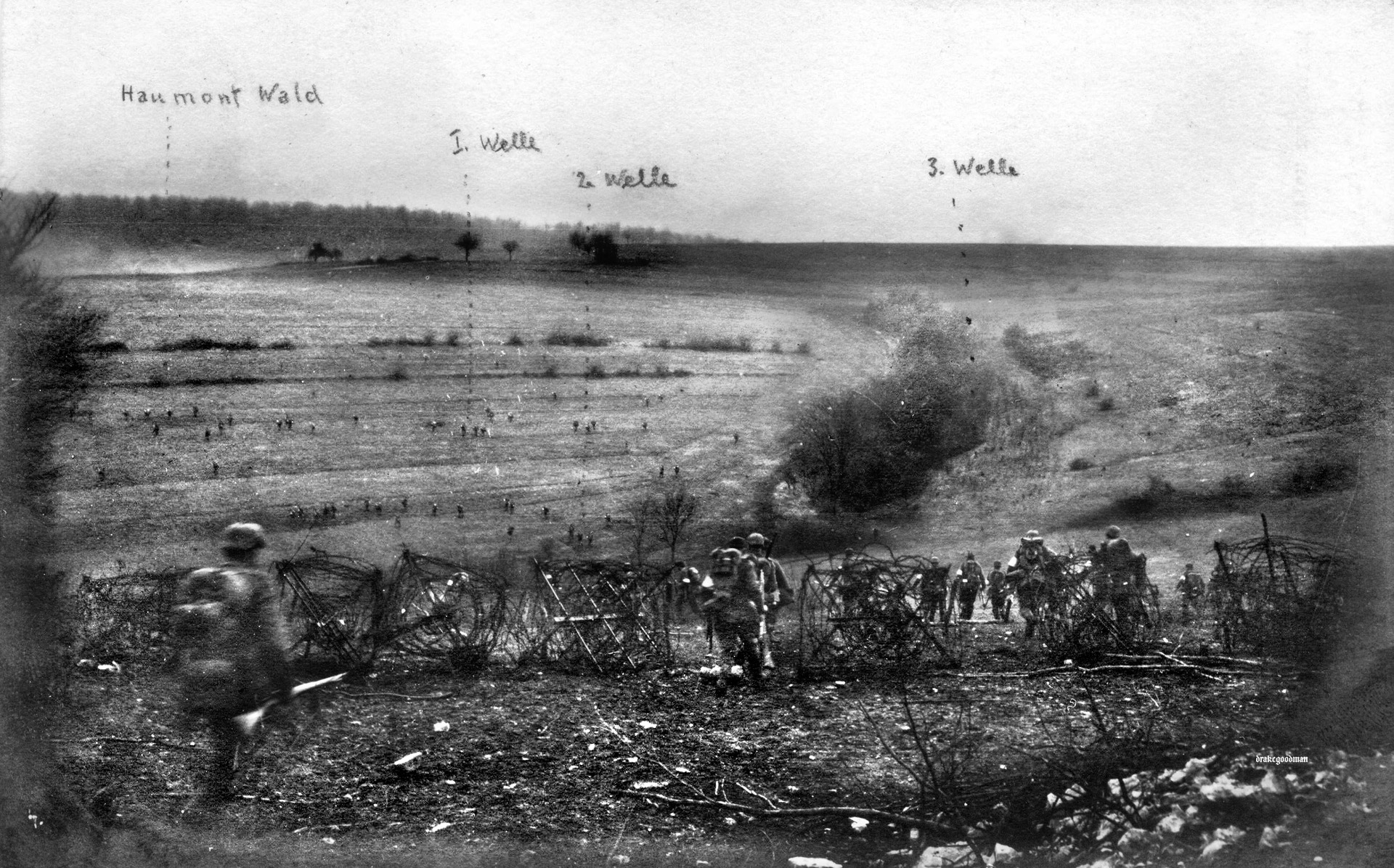

Worse lay in store for the French who survived the devastating artillery bombardment. The German infantry assault began at 4:00 pm. On a 19-mile front, 140,000 German troops charged out of the forests, quickly overwhelming the dazed and wounded French soldiers. Phone wires had been torn apart, cutting off all communication with Joffre’s headquarters. Rifle fire and machine guns cracked in the dense smoke reeking with the stink of cordite. Hand grenades burst in the trenches and dugouts, killing and maiming dozens in seconds.

The avalanche of Germans swept through the outer defenses and killed without mercy. Ninety-six flamethrower teams shot searing hot jets of pure fire into the defenders. The French 51st Division was routed by the terrifying weapons, running pell-mell to the rear with their clothes and hair aflame. Citizens hid in their cellars and waited for their brave troops to fend off the Germans.

Falkenhayn’s initial objective was to capture the outer ring of forts, from which he could repel the expected French counterattacks. All through the night the Germans fought ever closer to the forts. Driant’s two battalions held the Bois des Caures near the farming village of Flabas. He had repeatedly warned Joffre that Verdun was vulnerable and ripe for attack. Now he was proven correct in the most shocking way. With his 1,200 reservists, Driant faced 10,000 determined and well-trained Germans. Only 118 of his men were able to escape the slaughter. Driant was not among them. He had been struck in the head by a German bullet.

A lieutenant of the French 72nd Division managed to get a call to Joffre’s headquarters. “The commanding officer and all the company commanders have been killed,” he said. “My battalion is reduced to 180 men. What am I to do?” He had lost 420 men in two days. It was only then that the French High Command realized the full extent of the calamity.

The following day, February 24, the entire eight miles of the outer French trench lines had collapsed. As the Germans surged closer to forts Douaumont and Vaux, thousands of civilians huddled in cellars or gathered their possessions and embarked on a panicked flight. They clogged the roads and bridges the army needed to bring up fresh troops. Falkenhayn had hoped for this. If his men could take the forward slope of the heights over the Meuse, the German artillery could employ direct fire on the important bridges and roads leading north and west.

The once-mighty polygonal fortress Douaumont, nearly a quarter mile across, was defended by only 58 reservists under the command of a warrant officer. On February 25, a single sergeant of the 24th Brandenburg Regiment was found alone by the fort’s inner walls. He was astounded after carefully peering into a window, to see no defenders. He waved for a unit of pioneers to accompany him through the window. They were dumbfounded that no one was shooting at them. They entered through a window and captured the fort without a shot being fired.

The news of the fort’s fall was cause for celebration all across Germany. Schools were let out while church bells rang. When the French troops learned of their supposedly impregnable bastion’s capture, panic began to spread like chain lightning. Rumors that the bridges over the Meuse, their only escape route, were to be demolished heightened the fears. Food stores were being looted and the promised reinforcements were hesitant to enter the meat grinder at Verdun.

General Noel de Castelnau, Joffre’s chief of staff and a veteran with the Second Army at the Marne, reconnoitered the battered lines and made the fateful recommendation that they must be held at all cost. As a member of an old aristocratic family with a long history of military service, de Castelnau decided that Verdun was the place to prove the real test of French mettle.

Unfortunately, there were no rail lines leading to Verdun for the French to rush reinforcements to the sector. The south line had been cut off by the Germans in 1914, while the rail line to Paris had been under constant attack by the German Third Army from the Argonne Forest. All that were still open were roads, most of which were little more than dirt trails.

The youthful Crown Prince Wilhelm commanded the German Fifth Army in the first assault. “The moral effect of [our bombardment] was immense. Everywhere the infantry encountered only slight resistance.”

Wilhelm was one of the most experienced and respected generals in the German army. From the start he had opposed Falkenhayn’s plan to assault, but not capture, the city of Verdun. Wilhelm reasoned that an assault of that nature would demoralize his troops. Yet Falkenhayn wanted to use the captured French defenses to threaten the city and force the French to die in a series of bloody counterattacks.

But any bitterness among the German generals was of little interest to the French soldiers who were dying in ever-greater numbers. They needed reinforcements; even more, they needed someone to reverse the rapidly deteriorating situation.

General Henri Philippe Pétain, the sexagenarian commander of the French Second Army, took command of the deteriorating situation. A cantankerous and obstinate commander who had his share of enemies within the French high command, he was a genius at logistics and the use of concentrated artillery fire. Joffre personally despised Pétain, but he had little choice but to work with him.

“Cannons conquer, infantry occupies,” was one of General Philippe Pétain’s maxims. Pétain was suffering from pneumonia and arrived at Verdun on a litter. He quickly began assembling the force needed to defeat the German onslaught. He telephoned the commander of the newly arrived XXX Corps. “I have taken command,” he said. “Tell your troops to hold fast.” After assessing the immediate situation Pétain issued the famous order, “They shall not pass!”

Pétain faced two daunting tasks if he were to effectively counter the Germans at Verdun. First, the French needed a reliable line of supply to support their troops. Second, they needed more heavy guns and observation posts so that the fire from their guns would inflict substantial losses on the Germans.

The supply line became known as the Sacred Way. It was a corridor through which trucks shuttled key supplies to the French forces around the clock. The French employed 12,000 vehicles on the Sacred Way and detailed a division of engineers and support personnel to keep the road in good repair. The laborers filled shell craters and removed damaged vehicles that obstructed traffic.

Officers received orders that their foot soldiers were to march through fields or woods flanking the supply corridor, and that empty trucks carried wounded to the rear. At least one vehicle passed every 15 seconds. The Sacred Way carried approximately 2,000 tons of guns, ammunition, food, and medical supplies to the battlefront at Verdun. It also enabled regular resupply of gas masks, barbed wire, and communications equipment.

Pétain assembled 632 heavy and medium guns. The largest fired shells in excess of 15 inches in diameter and weighed more than a ton each. While the largest French guns were sited on fixed positions, German mobile artillery had to be moved ever closer to support the infantry advances. But with the frequent rains of winter in France, the fields and roads turned into sodden quagmires of mud. More horses had to be brought in to move the guns, which were quickly identified and hit by French artillery. Losses among the horses were horrendous.

By March German casualties had reached 82,000. French casualties were even higher, totaling 88,000 killed and wounded. Despite the horrifying casualties, French spirits remained high. One captured French officer was brought before the Kaiser himself, who had come to view the battle. “You will never enter Verdun,” he told the German leader.

This boast seemed to be supported by the fact that although the Germans had advanced to within four miles of the city itself, they could go no further. Falkenhayn, after conferring with Crown Prince Wilhelm, who was his most effective army commander, decided to change his plans. Attacking only on a narrow front on the east bank of the Meuse River had been a costly mistake. He subsequently ordered a two-pronged attack on the west bank of the river on March 5. In that location the terrain was better suited to an attacking army.

Falkenhayn’s first objective was for the German assault troops to capture or drive off the French artillery batteries that were shielded by a line of hills on the west bank. His second objective was the capture of Fort Vaux. The shattered village of Vaux, which lay in the shadow of the fort, had changed hands 13 times during March. But Fort Vaux remained in French hands, mocking Joffre’s opinion that fixed forts were obsolete. With a determined garrison of men who trusted their stone and concrete walls, the defenders of the old stronghold refused to allow the Germans to take permanent possession of it.

By early April Falkenhayn’s forces had made two major assaults. The first took place on the east bank, and the second unfolded on the west bank. Yet his weary and battered troops were no closer to taking Verdun itself. Wilhelm persuaded his commander to abandon the original strategy and order a full-scale attack along the 20 miles of the Verdun lines.

The Germans scheduled a major assault for April 9. On that fateful day every German division deployed around Verdun went forward in the wake of a massive artillery bombardment. What followed was four solid days of savage hand-to-hand fighting that left the crater-pocked landscape blanketed with thousands of dead and wounded.

Once again the resolute French held their ground. The weather aided the French. Heavy spring rains brought the fighting to a standstill. Other than artillery attacks by both sides, the remainder of April was relatively quiet. Both armies licked their wounds and caught their breath. The living shared their trenches and dugouts in the company of cold, rotting corpses. French troops suffering in icy cold and water sodden trenches did not see a single German. Yet the battle was far from over.

The German assault on Le Mort Homm, or Dead Man’s Hill, proved to be far more arduous when they realized that a higher and more heavily defended crest lay beyond. When the weather improved Wilhelm’s bedraggled and exhausted troops slowly fought their way up Le Mort Homm, at last taking the trenches held by the remnants of the 146th Regiment, which lost 144 of 175 men. But it was a small victory that had no effect on the integrity of the defenses. By this time Falkenhayn had lost more than 100,000 men.

Verdun had forced the French to divert 35 of the 40 divisions slated for the Somme offensive. The British would have to carry the burden of the assault. While Pétain recycled his troops to bring in fresh men on a regular basis, Falkenhayn refused to pull back his drained troops. This caused even more bitterness between himself and Wilhelm.

French artillery barrages had begun to take a heavy toll on the Germans in May. On average one died every 45 seconds. French deaths were even higher. Inside captured Fort Douaumont the German garrison endured the heavy French bombardment. Fort Douaumont had been employed for munitions storage. A battalion of troops were resting in a room on May 8 in which flamethrower fuel and hand grenades had been stored. One of the men whose was smoking accidentally touched off an explosion that killed as many as 679 German soldiers. Unwilling to take the time to bury the dead, the Germans simply walled up the room and continued the fighting.

The French incorrectly assumed that the explosion had decimated the German garrison. A common tactic of the French was to seize any opportunity to retake positions lost to the enemy. The French stormed the fort on May 22, but the Germans counterattacked the following day and retook the lost ground.

In early June Fort Vaux was again the German objective. The divisions of three German corps attacked on a three-mile front with one yard of space between each man. The ferocious attack was preceded by a barrage of 600 guns. The fort fell on June 7 after a determined defense led by Major Sylvain-Eugene Raynal, who kept headquarters informed by carrier pigeon. After savage close-in fighting in the underground tunnels, he only surrendered when they ran out of water. In an age where chivalry still had value, Crown Prince Wilhelm gave Raynal a sword to replace his lost one. With the Germans at last looking directly down into the city of Verdun just two miles away, victory seemed assured.

Although Pétain had done well, his indifference to the shocking casualties was too much for Joffre. He was replaced by General Robert Nivelle, who was a skilled artillery officer, and even more important, better respected than the taciturn and inflexible Pétain. Nivelle’s command of the French artillery soon overshadowed the German guns at last turning the tide in favor of the French.

The battle took an even more ghastly turn on June 22 when the Germans fired 116,000 phosgene gas shells on the French artillery positions, killing and wounding 1,600 men. This deadly bombardment was followed by an attack by the elite mountain troops of the Alpenkorps, but they had to withdraw when their line of supply was cut.

The high-water mark of the Verdun offensive occurred on June 23. Nearly 20 million shells on both sides had been fired by that time. The once-beautiful and peaceful terrain of the Meuse Valley resembled the pock-marked surface of the Moon. Thousands of shell craters stretched in every direction. Forests and towns, farms, and roads were nothing but memories. More than 200,000 men had been killed or wounded on each side.

Events on other fronts and in other sectors ultimately derailed Falkenhayn’s Verdun offensive. He was forced in June to transfer some of his troops to the Eastern Front to deal with the offensive masterminded by Russian general Aleksei Brusilov. The real turning point, though, came on the first day of July when the British unleashed their massive assault on the Somme. The Somme Offensive put Germans on the defensive.

The German Fifth Army forced its way closer to Fort Souville on July 11, which had been hit by more than 38,000 shells since April. Although they came to within just two miles of the city, Falkenhayn’s exhausted forces could advance no closer. The French defenses had held. Indeed, by that time the French had switched to the offensive.

Falkenhayn had lost the initiative. His grand plan had led only to another slugging match between entrenched armies. Kaiser Wilhelm demanded to know when the Verdun offensive would destroy the French army. But his general could only insist that his plan would soon succeed. He was wrong.

Verdun was no longer the focus of the Western Front. Falkenhayn cancelled the assault on July 12 and held his ground. But the pugnacious Kaiser had at last had enough. He ordered Falkenhayn relieved of command by the general staff. Disgraced by his association with the worst debacle in the history of the German army, the proud but still arrogant general left the field. He was sent to command the Ninth Army in Transylvania to capture the capital city of Bucharest.

The Kaiser demanded that the new chief of the general staff, Paul von Hindenburg, find a way to withdraw from Verdun in the least costly way. The fighting continued for another four months, with the French slowly regaining ground and re-taking the forts. The French retook Fort Douaumont on October 24 with surprisingly little effort. A larger attack, preceded by heavy artillery fire on December 15 re-captured much of the ground lost since the opening of the battle.

The French revenge was total. The shattered German troops were pushed back to the lines from where they had moved out in February. The Kaiser’s demoralized troops threw down their arms. The French rounded up 11,000 prisoners. From that point on, the Supreme Army Command committed nearly all its reserves on the Western Front to the Somme sector.

The Battle of Verdun had been an unremitting fight from February 21, 1916, to December 18, 1916. Verdun had changed the course of the war, but not in the way Falkenhayn had predicted. It proved to be a costly defeat for Germany, and an even more costly victory for France. Falkenhayn’s pledge that only two Germans would die for every five Frenchmen turned out to be nothing more than an empty boast. As events turned out, the ratio was closer to four to five.

When the battle drew to a close, more than one million men had died or been maimed in the great battle. To this day only 290,000 bodies have been recovered, with less than two-thirds identified. More than 700,000 dead soldiers are unaccounted for at Verdun.

The outcome of the Battle of Verdun stands as a metaphor for the stagnant trench warfare of World War I. By the time the terrible battle drew to a close in mid-December, the French had returned roughly to their position before the battle began. Little had been gained by either side, and so much lost.