By Mike Phifer

Major General Patrick Ronayne Cleburne rose to his feet in the early afternoon of November 30, 1864, when he saw the courier galloping toward him. Cleburne had been playing a makeshift game of checkers with a staff officer at the bottom of Winstead Hill a couple of miles south of Franklin, Tennessee, killing time until his division caught up with him. He was also trying to keep his mind off the anger and hurt that was burning inside of him.

After being informed by the courier that Lt. Gen. John Bell Hood, the commander of the Confederate Army of Tennessee, wanted to see him at his headquarters, Cleburne mounted his horse. He rode toward the Harrison House, located about a half mile south of Winstead Hill, where Hood had set up his headquarters.

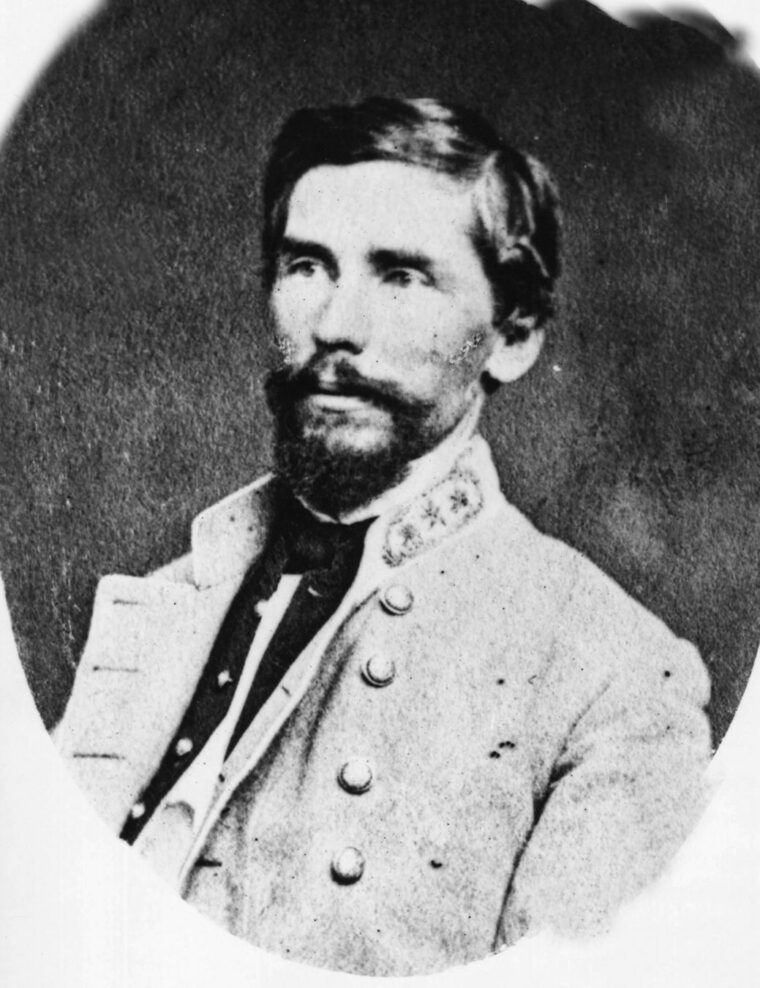

Cleburne was incensed with Hood for accusations he had made against him that morning. The previous night the Federals had been allowed to slip away from Spring Hill and retreat toward Franklin, escaping Hood’s plan to crush them. Hood blamed Maj. Gen. Benjamin Cheatham, Cleburne’s corps commander, as well as Cleburne himself and Maj. Gen. John Brown, another divisional commander in the corps, for allowing the Yankees to escape. Cleburne’s division had a well-earned reputation as a tough, dependable division, and Hood’s accusation stung fiercely. Cleburne was determined to erase Hood’s accusations against him.

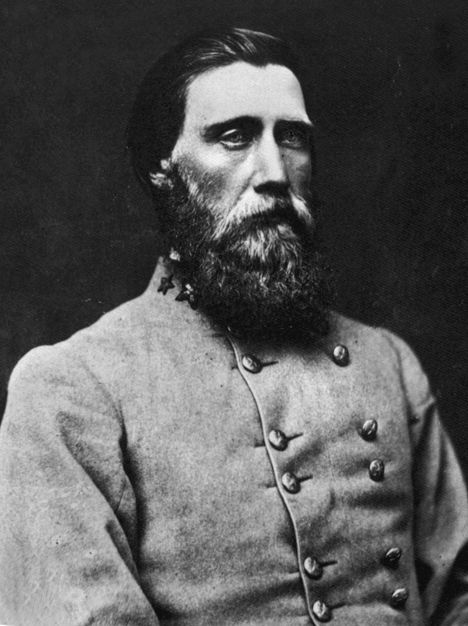

Upon reaching the Harrison House, Cleburne joined Cheatham and Brown as well as Maj. Gen. William Bate, another divisional commander from Cheatham’s corps; Lt. Gen. Alexander Stewart, a corps commander; and the outspoken cavalry commander, Maj. Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest. Although not all of his army was there yet, Hood was not going to wait for them. He informed his generals he planned to make a frontal assault against the entrenched enemy at Franklin. Hood believed the Federals had no intention of making a stand at Franklin but instead were just covering their retreat. With a good push, he might finish them instead of fighting them at Nashville, which the Federals had been fortifying since they captured it in 1862.

Forrest thought it a bad idea and advised Hood not to make a frontal attack as the enemy was well fortified. Instead, Forrest said, “Give me one strong division of infantry with my cavalry, and within two hours’ time I can flank the Federals from their works.” Cheatham concurred. “I do not like the looks of this fight,” he said. “The enemy has an excellent position and are well fortified.”

Hood would not be dissuaded. He not only wanted to crush the Yankees but also restore his army’s fighting spirit, which he thought was lacking. As the meeting adjourned Hood followed Cleburne outside and reminded him of his orders. Cleburne replied, “I will either take the enemy’s works or fall in the attempt.” Sadly, Cleburne had only hours left to live.

Cleburne was born on March 16, 1828, in County Cork, Ireland. His father was a physician who, after his first wife died, remarried and moved to an estate. Supporting his estate kept Dr. Joseph Cleburne’s finances tight and he was unable to send Patrick to a school in England. Instead, young Cleburne was sent away to a nearby Protestant school at the age of 12.

Three years later tragedy struck when Patrick’s father died and left his wife in financial difficulty. To lessen the family burden, Patrick left school and took an apprenticeship with a medical colleague of his father. Young Cleburne became quite efficient at mixing medicine and decided he wanted to make it his profession. It was not to be; his application to be a student in the Apothecaries Hall, Trinity College, in Dublin was rejected twice. Then things got worse.

Hardships in mid-1840s Ireland forced his employer to let young Cleburne go. Not willing to return home and put more financial stress on the family, Cleburne went to Dublin where he once again failed to gain admission in the Apothecaries Hall. Believing he had disgraced his family and with few options left, Cleburne joined the British Army.

Enlisting in the 41st Regiment of Foot, Cleburne remained in Ireland due to political and civil unrest for more than three years, eventually obtaining the rank of corporal. When he turned 21, he received some money from his deceased mother’s dowry that allowed him to purchase a discharge. Although his military training would serve him well in the coming years in the service of the Confederacy, he was glad to leave the Army. Less than two weeks after his discharge, Cleburne and three of his siblings boarded a ship for America.

The day after Christmas 1849, Cleburne set foot in New Orleans. He set out almost immediately for Cincinnati, Ohio, where he had a relative and spent the winter working in a drug store. The following spring he moved to Helena, Arkansas, where he found employment managing a drugstore. The shy young man did well but eventually left the business to become a lawyer.

Cleburne helped organize a militia company in 1860 called the Yell Rifles. He was elected captain of the company, and he drew upon his experience in the British Army when drilling the eager volunteers. Cleburne, who saw himself as an Arkansan, was determined to support the people of the state who had given him their unflinching support.

When war broke out on April 12, 1861, the Yell Rifles were combined with nine other volunteer units and became the 1st Arkansas Volunteer Infantry with Cleburne as their colonel. A stern leader, Cleburne nevertheless looked out for the welfare of his men. Cleburne’s well-drilled regiment soon found itself in a brigade under the command of Brig. Gen. William Hardee.

Cleburne led his men into their baptism of fire at Shiloh on April 6, 1862. The Irish-born officer, who had been promoted to brigadier general the month before the battle, led Hardee’s old brigade, something he had been doing since the previous fall when Hardee was promoted to division commander. In the two days of bloody fighting at Shiloh Church, Cleburne’s brigade lost a shocking 1,043 killed, wounded, and missing out of 2,750 troops.

In the days following the defeat at Shiloh, Cleburne set out to rebuild his brigade. The battle had given Cleburne valuable combat experience which he used to improve himself and his men on the battlefield. It was during the Confederate invasion of Kentucky that Cleburne would become an acting division commander. His brigade was temporarily detached from the Army of the Mississippi under General Braxton Bragg and assigned to Maj. Gen. Kirby Smith’s Army of East Tennessee. Smith was heading north for Kentucky from Knoxville through east Tennessee, while Bragg was setting off from Chattanooga through central Tennessee. The two loaned brigades were formed into a small division and put under the command of Cleburne.

While organizing a counterattack during the fighting at Richmond, Kentucky, on August 30, Cleburne took a bullet through his left cheek. Although he tried to remain in the battle, he was soon unable to speak and had to seek medical help. A month later Cleburne was back with his brigade in Bragg’s army, and he again was wounded at the Battle of Perryville on October 8.

After retreating to Tennessee after the failure in Kentucky, the Army of the Mississippi was reorganized and renamed the Army of Tennessee. Cleburne was promoted to the rank of major general on December 12 at the recommendation of his departing division commander, Maj. Gen. Simon Buckner, his corps commander Hardee, and army commander Bragg. Cleburne took over the division despite there being two other brigade commanders with more seniority.

Cleburne led his division into action at the Battle of Stones River on December 31 where his men smashed the Union’s right flank and drove it back three miles. Despite the success of the first day, the second day of battle did not go well for Bragg, and his army was soon in retreat.

In the coming months the former British army corporal continued to drill his division, making it one of the best in the Army of Tennessee. The division’s fame had allowed them to keep their distinctive rectangular blue battle flag with an oval white moon in the center, while the rest of army’s units were ordered to fly the Confederate battle flag with the St. Andrew ’s Cross. The men of Cleburne’s division loved their blue battle flag, which they had carried under the two previous division commanders. It was a high compliment to be allowed to continue to carry the flag, but as Cleburne’s adjutant, Captain Irving Buck, wrote, “Like all luxuries it was costly and carried with it penalties, for the enemy had learned to whom the flag belonged, and where it appeared there was concentrated their heaviest fire.”

The blue battle flag was fluttering again as Cleburne led his division forward on September 19, 1863, at the Battle of Chickamauga. For two days Cleburne’s division was in the thick of the fighting. As a result, it suffered 1,743 casualties. After the Battle of Chickamauga, the Union Army withdrew to Chattanooga.

In summer 1863, Hardee had been dispatched to Mississippi, and Lt. Gen. Daniel Harvey Hill assumed command, replacing Cleburne. Hill and other officers under Bragg’s command had openly expressed their displeasure with Bragg for not immediately capitalizing on the Confederate victory at Chickamauga. In response, Confederate President Jefferson Davis visited the army to address the matter. He ruled in favor of Bragg despite widespread distrust of him. Davis gave Bragg permission to remove Hill. Hill left the army in October and was replaced by Maj. Gen. John Breckinridge. Hardee returned to the army in late October and took command of Cheatham’s corps, with Cheatham taking command of a division in it. Cleburne’s division was then transferred to Hardee’s command.

Positioned on the northern end of the Confederate position on Missionary Ridge overlooking Chattanooga, Cleburne’s 4,000-strong division repulsed repeated Federal assaults on November 25. It was a significant achievement considering Cleburne’s division was outnumbered by the attacking Union forces by four to one. Despite Cleburne’s success, the Federals at Chattanooga broke the Confederate center on Missionary Ridge. While Bragg’s army attempted to limp away, Cleburne’s division held back a Federal force for four hours at Ringgold Gap, allowing the Army of Tennessee and their wagon train to escape.

Nicknamed the “Stonewall of the West” by Confederate President Jefferson Davis, Cleburne was again proving himself a very capable commander with a division “reputed to be the best in Bragg’s Army,” as one Union officer stated. It was not to be Bragg’s army for long, though, as he resigned much to relief of many of his senior officers, including Cleburne, who had been in the group against him. General Joseph E. Johnston soon took command of the army.

Cleburne’s division would see plenty of fighting in the spring and summer of 1864 as Union General William Tecumseh Sherman advanced on Atlanta. Unhappy with Johnston’s tactics, Davis sacked him on July 17 and replaced him with Hood. Davis wanted an aggressive commander. That’s exactly what he got, albeit one who knew little more than how to attack in force. Hood had commanded a corps in the Army of Tennessee since late February, when he took over Breckinridge’s old corps (a job Cleburne was expected to get) and his promotion now left a vacancy. Cleburne again was passed over for the promotion and the position eventually went to Stephen D. Lee, who was promoted to lieutenant general on June 23, 1864.

Nevertheless, Cleburne did temporarily command a corps under Hardee during the August 31 clash at Jonesborough south of Atlanta. Hardee’s two-corps attack was repulsed. The following day, the Federals counterattacked; in the process, they nearly breached Cleburne’s line when they overran Brig. Gen. Daniel Govan’s brigade. Fortunately for the Confederates, Cleburne plugged the breach with another brigade. But with the Confederate’s last remaining railroad line into Atlanta cut, Hood evacuated the city. Hardee’s attack at Jonesborough was “a disgraceful effort,” said Hood.

Hardee did not remain under Hood’s command for very long. On September 27, Davis gave Hood permission to transfer Hardee out of his army. With Hardee gone, command of his corps went to Cheatham. Cleburne thought of leaving, too, but stayed out of loyalty to his division.

After consultation with Davis, Hood was to pull his army back to northern Georgia and operate against the vital Western and Atlantic Railroad that supplied Sherman’s forces. It was hoped the Federal commander would be forced to come out of Atlanta and fight on ground of Hood’s choosing. Sherman followed Hood for a short time but eventually broke off his pursuit.

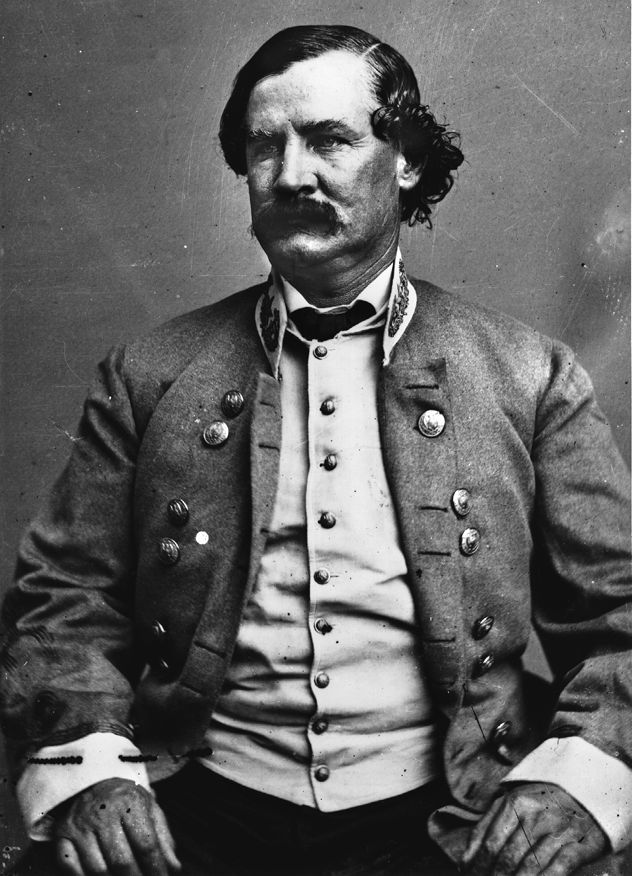

At that point, Hood decided to take a bold gamble. He planned to march north to Nashville in an effort to draw Sherman out of Georgia. Once he had captured Nashville, Hood then planned to continue advancing north until he reached the Ohio River. From there he would push east and link up with General Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia.

On October 30, Lt. Gen. Stephen D. Lee’s corps crossed the Tennessee River at Florence, Alabama. For the first three weeks of November bad weather and the slow arrival of supplies stalled Hood at Tuscumbia on the south of Tennessee River. Forest was raiding in west Tennessee, and Lee waited for the cavalry commander to join him.

Hood embarked on his desperate venture in a winter storm on November 21. The Army of Tennessee numbered 38,000 men and was divided into three infantry corps. In addition, the army benefited from the attachment of Forrest’s cavalry corps with its large complement of artillery. On the right was Stewart’s corps marching on the road to Lawrenceburg, in the center was Lee’s corps marching on back roads to Henryville, and on the left was Cheatham’s corps moving along the road to Waynesboro. Cleburne’s division led the way for Cheatham, marching through mud and pelted with sleet. Forrest’s cavalry screened the advance.

The Federal commander in Nashville, Maj. Gen. George Thomas, could field 70,000 troops to face Hood. But the Federal troops were spread out, including two divisions coming from Missouri. The IV Corps under Maj. Gen. David Stanley, and the XXIII Corps under Maj. Gen. John Schofield were dispatched by Sherman to reinforce Thomas should the Confederates attack. While Thomas strengthened his position at Nashville, Schofield, who was 75 miles to the south at Pulaski, Tennessee, was ordered to delay Hood’s advance. Schofield commanded two corps totalling about 25,000 men as well as a detachment of cavalry.

Upon hearing of Stewart’s corps reaching Lawrenceburg, which put them about halfway to the key town of Columbia along the Duck River, Schofield became concerned he might be cut off from Nashville. On November 22, he got his troops marching north in the rain and mud for Columbia, hoping to beat Hood’s men. Two days later he won the race to Columbia.

That same day, Cleburne and his division arrived at Ashwood. Nearby was the plantation home of good friend Brig. Gen. Lucius Polk, who had commanded a brigade in Cleburne’s division until he was severely wounded in June. Spotting a scenic little chapel nearby, Cleburne said, “It is almost worth dying to rest in so sweet a spot.” His words would turn out to be prophetic.

Cleburne’s division soon deployed with the rest of Hood’s infantry in front of Columbia to find the Federals had dug an arc of entrenchments south of the town. Schofield evacuated his troops to the north side of the Duck River on the night of November 27 and burned two bridges as he went. Despite this, Hood had a plan to crush the Federal force. While Forrest drove off the Federal cavalry, Cheatham and Stewart’s men would cross at Davis’s Ford a few miles east of Columbia. Then they would strike out for Spring Hill, 12 miles behind Schofield’s position, and block his retreat route. Meanwhile, most of the artillery and two divisions from Lee’s corps would remain at Columbia to keep Schofield occupied.

Cleburne’s division set out early on the morning of November 29 for Davis’s Ford, reaching it around 7 am. Crossing the Duck River on a pontoon bridge, the tattered column of Cleburne’s men, some of them shoeless, pushed north for Spring Hill on roads east of the main Columbia-Franklin Pike. Riding with Cleburne at the head of the lead brigade was Hood, who was strapped to the saddle due to battle injuries from Gettysburg and Chickamauga that resulted in major damage to his left arm and amputation of his right leg, respectively. Behind Cleburne’s division followed the rest of the Cheatham’s corps and behind them Stewart’s corps with a division from Lee’s corps.

Earlier Schofield received word from Union cavalry commander Maj. Gen. James Wilson that the Rebels were laying a pontoon bridge across the river and were likely heading for Franklin. He advised Schofield to retire his whole force along the Columbia-Franklin Pike. Schofield was skeptical; nevertheless, he began marching north to Spring Hill with his supply train, reserve artillery, and two divisions from Stanley’s IV Corps. One of these divisions was to be deployed at Rutherford Creek, located a third of the way between Spring Hill and Columbia, to secure the crossing there on the main pike.

Meanwhile, Forrest continued to drive the Federal cavalry north and east. “The enemy gradually fell back, making resistance only at favorable positions,” wrote Forrest. After a sharp skirmish at Mount Caramel, five miles east of Spring Hill, the blue-coated horsemen continued to fall back toward Franklin, while Forrest, leaving a brigade to keep an eye on them, galloped hard for Spring Hill.

Stanley was about two miles south of town when a hard-riding courier told him that Forrest was headed toward Spring Hill. Stanley got his men moving at double time and the lead brigade under Colonel Emerson Opdycke arrived in time to reinforce the two regiments garrisoning the town to repulse an attack by Forrest’s leading division. Brig. Gen. George Wagner’s division soon arrived, and Stanley deployed his 5,000 men behind makeshift breastworks to cover the town and the vital Columbia-Franklin Pike. Forrest could do nothing but skirmish with the Federals and wait for the infantry as his men began to run low on ammunition.

After trudging along muddy roads for hours, Cleburne’s division finally splashed across Rutherford Creek around 3 pm. Spring Hill lay only about 21/2 miles to the northwest. While Cleburne was ordered to advance to the Columbia-Franklin Pike and turn south to block Schofield’s retreat route, Cheatham was to remain at the ford and wait for the arrival of Maj. Gen. William Bate’s division of his corps and then lead it to Cleburne’s support.

After advancing about a mile and crossing McCutcheon’s Creek, Cleburne put his three brigades into battle order. Hood soon appeared and ordered Cleburne to advance in echelon formation. With Brig. Gen. Mark Lowrey’s brigade on the right and somewhat advanced, Brig. Gen. Govan’s brigade in the center, and Brig. Gen. Hiram Granbury’s brigade on the left, the 3,000 men of Cleburne’s division set off at about 3:45 pm with the sun sinking in the western sky. Cleburne’s remaining brigade under the command of James Smith was with the army’s supply train and would not catch up until early December. Covering Cleburne’s right flank was Forrest and a brigade of his men who still had some ammunition.

With no time to reconnoiter the Federal lines, Cleburne’s division set out across fields, getting part way to the Columbia-Franklin Pike, when they came upon Brig. Gen. Luther Bradley’s brigade of the 2nd Division which was positioned behind makeshift breastworks of fence rails in a wooded area. Lowrey’s brigade supported by Govan’s brigade on its left drove the Federals off, sending them running for their lives toward Spring Hill. The Confederates chased after them through the trees but were soon brought up short when they came out in the open along a creek. They came under fire from 18 guns the Federals had lined up on some high ground south of town near the pike.

Adding to Cleburne’s misery, two more guns posted on the pike fired against his men. Granbury’s brigade, which did not charge with the other two brigades, drove off the two guns and supporting infantry. Cleburne recalled his men and sent word to Cheatham of what was going on. An artillery shell burst overhead, severely wounding his horse. The Federals, seeing Cleburne’s blue battle flag, braced themselves for another assault.

It was not to come. Sometime around 5 pm, Maj. Gen. John Brown had arrived with his division and was forming on Cleburne’s right. Cheatham, who was unaware of Hood’s intention to block the pike, was planning an attack against Spring Hill. Brown was to attack to Cleburne’s right, and once the Irishman heard the gunfire he was to attack as well. Bate’s Division was to attack on Cleburne’s left.

Hood had sent this division to march to the Columbia-Franklin Pike and then swing south. An aide of Cheatham found the division and directed it to move north and make contact with Cleburne, who was still listening for the sound of Brown’s gunfire. It never came because Brown decided not to attack, telling Cheatham he did not want to expose his right flank to an attack from Federals reported to be north of him. Hood postponed the attack when Cheatham informed him of Brown’s concern, although he did order Stewart’s corps to advance on Brown’s right and seize the pike north of Spring Hill. Stewart got lost in the dark and soon reported to Hood that his men were tired and hungry and needed rest. Hood told him to bivouac for the night. Hood then asked Forrest to block the pike with his cavalry. The cavalry commander promised to do the best he could, but with his men low on ammunition and worn out, there was little he could do. The Columbia-Franklin pike remained open.

While campfires flickered in the darkness as the worn-out Confederate troops prepared to make their meals and get some rest, Schofield’s bluecoats retreated up the open Columbia-Franklin Pike. Realizing the danger he was in, Schofield ordered a withdrawal mid-afternoon. At 7 pm, the lead Federal brigades reached Spring Hill, slipping past the Rebels who at some points were a few hundred yards from the pike. On through the night Federals retreated north to Franklin, reaching it at about 4:30 am on November 30.

When he awoke in the morning and learned that the Yankees had escaped, Hood was “wrathy as a rattlesnake,” said Maj. Gen. John Brown. At a breakfast meeting with some of his senior officers he blamed Cheatham and by extension Brown and Cleburne, who he had personally ordered to take the pike.

As the Confederates set out after the Federals, Stewart’s corps led the way followed by Cheatham’s corps. Forrest continued to ride ahead and hurry along the Federal rear guard. Cleburne, meanwhile, was hurt and angered when he found out that Hood thought him partially responsible for the Federal escape. In discussing the matter with Brown, Cleburne told him he thought the responsibility rested with Hood, who “was upon the field during the afternoon and was fully advised during the night.” Cleburne told Brown they would speak more on this, but they never did.

After leaving the meeting with Hood in the early afternoon, a despondent Cleburne headed over to tell his brigadier generals of the order to attack Franklin. “Well, General, there will not be many of us that will get back to Arkansas,” said Govan. Cleburne replied, “Well Govan, if we are to die, let us die like men.”

While his brigadier generals got their men moving, Cleburne rode ahead stopping north of Breezy Hill, which was located east of Winstead Hill. Between these hills ran the Columbia-Franklin Pike. These hills had earlier in the day been held by Wagner’s division until they evacuated them when the Rebels threatened to flank them. Cleburne joined a detachment of sharpshooters on a rocky hill and commented that he had left his field glasses behind and asked if he could borrow a telescope. Lieutenant John Ozanne quickly detached the long telescope from his Whitworth rifle, focused it, and handed it to Cleburne.

The sharpshooters had a good position from which to view the Yankees at Franklin, and Cleburne soon got an eyeful as he rested the telescope on a stump and peered through it. The Federals had been busy in Franklin. The Tennessee town was snuggled on the south side of a bend in the Harpeth River. There were two bridges in town, but they were both damaged. Schofield had been expecting pontoons, but they had not yet arrived from Thomas, so he took charge of the repair of the bridges, and he ordered his 3rd Division commander, Brig. Gen. Jacob Cox, to take command of the defenses of Franklin with orders to “hold Hood back at all hazards till we can get our trains over, and fight with the river in front of us.” At this point the river was at their back.

Setting up his headquarters in the brick Carter House, Cox quickly put the bluecoats to work digging trenches or improving existing ones and constructing breastworks. With the Carter House as the central point near where the pike ran through, the Federal line was anchored by the river on either side of the town. The ground in front of the Federal position was to Cox’s liking as it was mostly open for about two miles. To hold the line, Cox had the three brigades of his division positioned on the left, stretching from the river and railroad line to the Columbia-Franklin Pike, where the road was left open through the Federal entrenchment. A second line was constructed about 250 yards to the north near the Carter House.

Brigadier General Thomas Ruger’s division, minus one brigade, was positioned on the west side of the Columbia Pike. To their right was positioned Brig. Gen. Nathan Kimball’s division from the IV Corps, which stretched to the river on the right. Brig. Gen Thomas Wood’s division of the same corps was posted across the river to protect the bridges under repair and guard the supply wagons once they rolled across the repaired bridges. Brig. Gen. George Wagner’s division, which was acting as the Federal rear guard, took up a position about 800 yards in front of main entrenchment with Colonel Joseph Conrad’s brigade on the east side of the main pike and Col. John Lane’s brigade on the west side. Wagner’s 1st Brigade commander, Colonel Opdycke, bluntly refused to deploy his men in such an exposed position and promptly marched his men behind the Union line. Schofield had strengthened his front line with artillery pieces and also positioned artillery at Fort Granger deep behind the Union left flank. Maj. Gen. Wilson’s cavalry brigades were posted east of town on both sides of the river.

After he finished surveying the impressive Union lines, Cleburne said, “They have three lines of works, and they are all completed.” He then returned to his division where he oversaw its preparations for the attack.

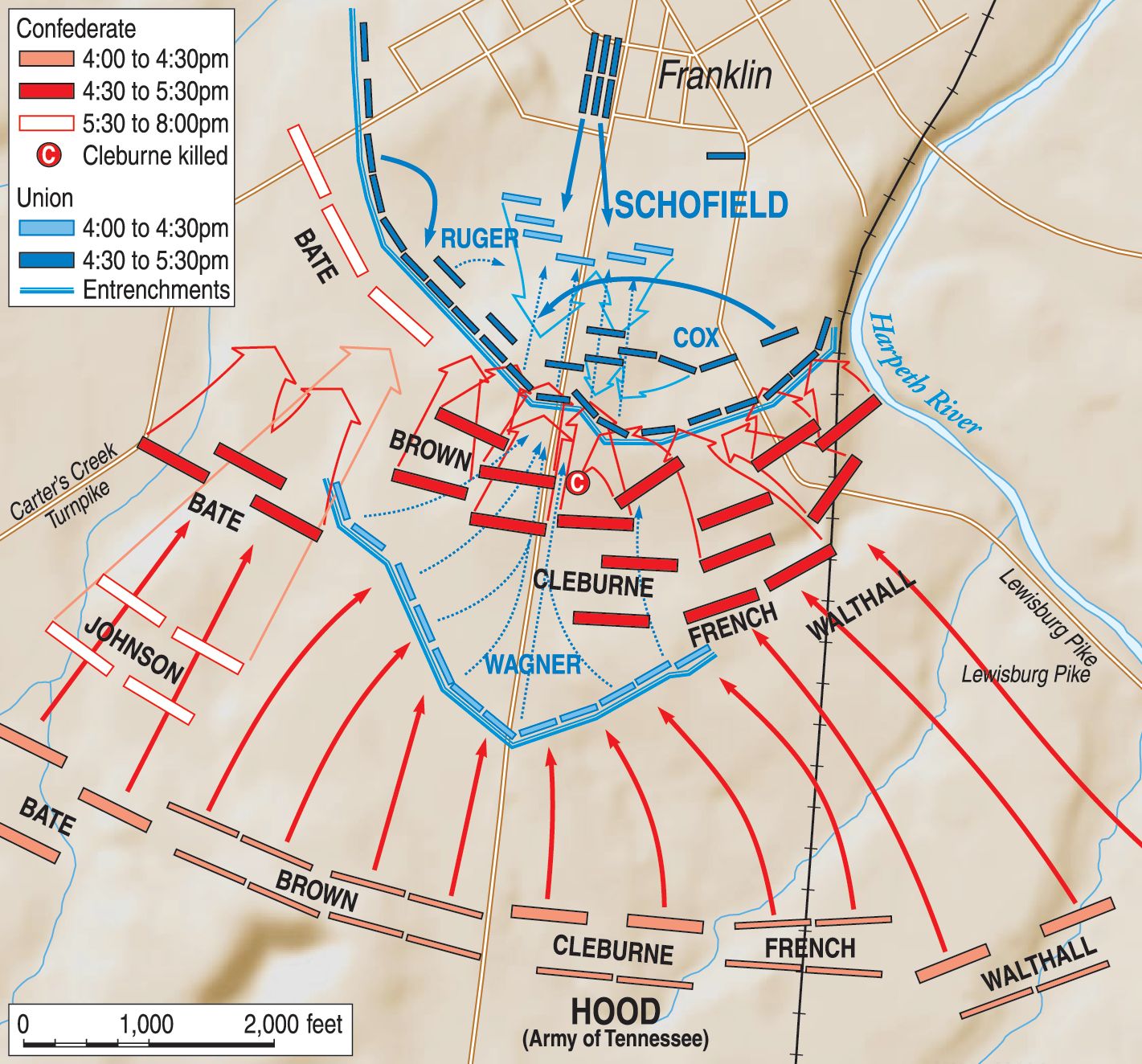

Hood’s plan of attack was to have Maj. Gen. William Loring, Maj. Gen. Edward Walthall, and Maj. Gen. Samuel French’s divisions of Stewart’s corps advance on the eastern side of the open ground and attack the Federal left. Covering Stewart’s right flank would be dismounted troopers from Forrest’s cavalry advancing along the river. Bate’s and Brown’s divisions of Cheatham’s corps would attack across the open ground west of the Columbia-Franklin Pike, while Cleburne’s division would attack on the east side of the pike. To his right would be French’s division. Dismounted troopers would cover the far left of Cheatham’s corps. Lee’s corps with most of the artillery had not arrived yet, but by 3:30 pm with only an hour of daylight left Hood decided not to wait any longer to attack. Lee’s corps would act as the army’s reserve when it arrived from Columbia.

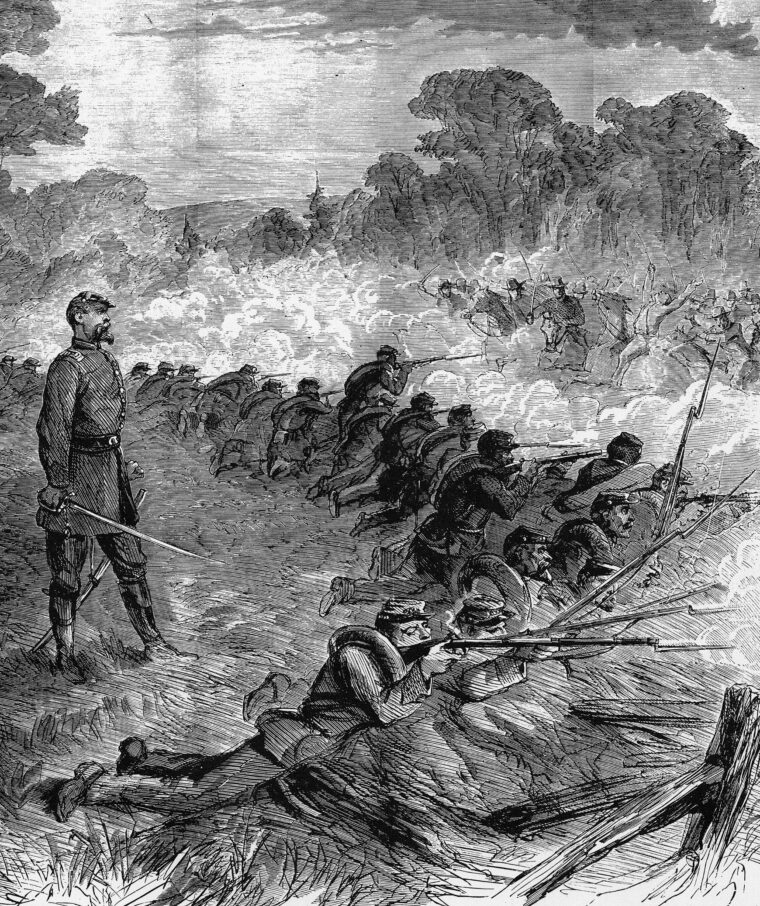

It was nearing 4 pm when 20,000 tattered Confederates in gray and butternut moved forward, their battle flags fluttering. Rabbits scurried and coveys of quail fluttered to get out of way of the six divisions and their skirmishers. Federal artillery quickly began to open up on the advancing Rebels.

As they moved closer to the enemy, Cleburne called in his skirmishers and deployed his three brigades, which had been advancing in column formations into line. With Brig. Gen. Hiram Granbury’s brigade of mostly Texans on the left, Govan’s brigade of Arkansans in the center, and Brig. Gen. Mark Lowrey’s brigade of Alabamians and Mississippians on the right, they closed within 50 yards of the 2,000 men of Conrad’s brigade. The enemy fired a strong volley. Cleburne’s men briefly halted, and then they charged the Federals at the double quick, screaming the blood-curdling Rebel yell.

The Federals broke as did men of the Lane’s brigade as they faced not only Cleburne’s division, but also elements of Brown and French’s divisions. As the bluecoats ran hard for their main line, someone among the Confederates shouted, “Go into the works with them!” The cry was taken up as Cleburne and Brown’s men surged after them, killing or capturing the slower ones. It was now a deadly race to the Union lines in the center.

On Cleburne’s right, Stewart’s corps swept toward the Federals’ entrenchment and were greeted by an appalling fire. Enfilading artillery fire from across the Harpeth River added to the Confederate’s misery. A grove of locust trees that the Federals had turned into an abatis slowed down some of attacking brigades, prolonging the men’s exposure to the deadly fire of the Union troops, some of whom were sporting repeating rifles. Despite the storm of lead, some Rebel troops managed to reach the breastworks, only to be pinned down or killed. Brig. Gen. John Adams managed to get atop of the breastworks on his horse and grab the colors of one of the Federal regiments. Both Adams and his horse were shot down. The attack on the Federal left had failed with grievous casualties.

Meanwhile, Cleburne continued to urge his men on as they ran toward the Federal lines. Cleburne’s borrowed horse was shot out from under him 100 yards from the Federal works. One of his staff officers, Lieutenant Jim Brandon, quickly dismounted and offered Cleburne his horse. As Cleburne was about to swing into the saddle, this horse also was killed. Drawing his sword, Cleburne charged on foot toward the Federal lines.

By this time, a wall of flame had exploded from the enemy works as the bluecoats poured a deadly fire into both Cleburne and Brown’s men. Granbury, who was leading his Texans forward, was shot in the head. More men went down, but still the screaming Rebels came on. They pressed through the gap in the Union lines where the Columbia-Franklin Pike entered the town. Meanwhile, Cleburne got to within about 50 yards of the Federal line when a bullet struck his chest. He was killed instantly. No one at that the time seemed to notice, and his men surged through the gap in the enemy’s line.

Brutal fighting raged around the Carter House and a cotton gin located to the east of the pike near the entrenchment, as Cleburne and Brown’s men attempted to widen the 200 yard gap and split Schofield’s force. The Confederates swung some captured artillery pieces on the bluecoats, only to discover there were no primers. “A mass of frightened recruits and panic-stricken men came surging back,” said an officer in Opdycke’s 1,500-man division as they entered the deafening meat grinder around the Carter House to plug the gap. More Federal troops arrived to help and slowly the Confederates were driven back to the breastworks were they grimly held on. The Federals were forced to construct a barricade at the garden of the Carter House as each side continued to pour a withering fire into the other. Any attempt by Cleburne’s men to renew the attack was driven back. The men decided to wait for Cleburne’s order to attack but it never came. “I knew Pat Cleburne was dead for if he had been living they would have been ordered to attack yet again,” said one Confederate soldier.

Meanwhile, the attack made by Bate’s division, which was deployed on Confederate left, had failed. Maj. Gen. Edward Johnson’s division of Lee’s corps was sent into the fray sometime after 7 pm in the dark. Johnson’s assault failed and only added to the body count. The firing sputtered out around 10 pm. An hour later the bluecoats started to cross over the Harpeth River. By the morning of December 1, Schofield’s army had again given Hood the slip as they headed north to Nashville. Hood would follow after Schofield to Nashville, and his wounded army would be shattered in the same manner of frontal attack as occurred at Franklin.

November 30 had been a bloody day for the Confederates. They lost an estimated 7,000 men of which 1,750 were killed. The Federals lost around 2,300 men. Cleburne’s division suffered more than 1,700 casualties, which was about half its force. Cleburne’s body was found the next day with his boots missing. He was buried in Columbia that afternoon, but not for long. When Lucius Polk found out about Cleburne’s comment on the little chapel on his estate, he had the general’s body moved there. Nobody was quite comfortable with having Cleburne in the cemetery at Columbia where Yankees had been buried. Cleburne’s body would be moved again in 1870 to a cemetery overlooking Helena, Arkansas. It would be his final resting place.

A few years after the Battle of Franklin, Cleburne’s old friend and commander Hardee would write of the native Irishman and his men this accolade: “Where this division defended, no odds broke its lines; where it attacked, no numbers resisted its onslaught, save only once.” It was a fitting tribute to one of the South’s greatest generals.

Brilliant history…..about a great military man…..from Ireland….and a hero of the Southern Confederated States….