By Peter Suciu

The basic shape of the American M1 helmet and the Soviet M40 helmets became iconic symbols of the Cold War and remain popular with collectors today. Each has a shape that is easily distinguishable and each served as inspiration as the headgear of choice for countless nations in their respective spheres of influence. More important, both the American and Soviet steel combat helmets were created as a necessity for the new type of war that military planners in each nation saw brewing. While France, England, and even Germany kept the basic shape and pattern of their World War I helmets, modernizing various features—and in the German case making drastic improvements—the Soviets and Americans developed helmets that were still considered ideal for nearly 50 years after their introduction.

Even more noteworthy is the fact that neither nation—in the Soviet’s case their Russian predecessors—even entered World War I with their own protective headgear, but instead relied on what the Allied powers of the day could provide. In turn, both America and Russia did produce their own versions but for the most part their early helmets essentially relied on the patterns already developed by the French and British.

Origins of Soviet Helmets

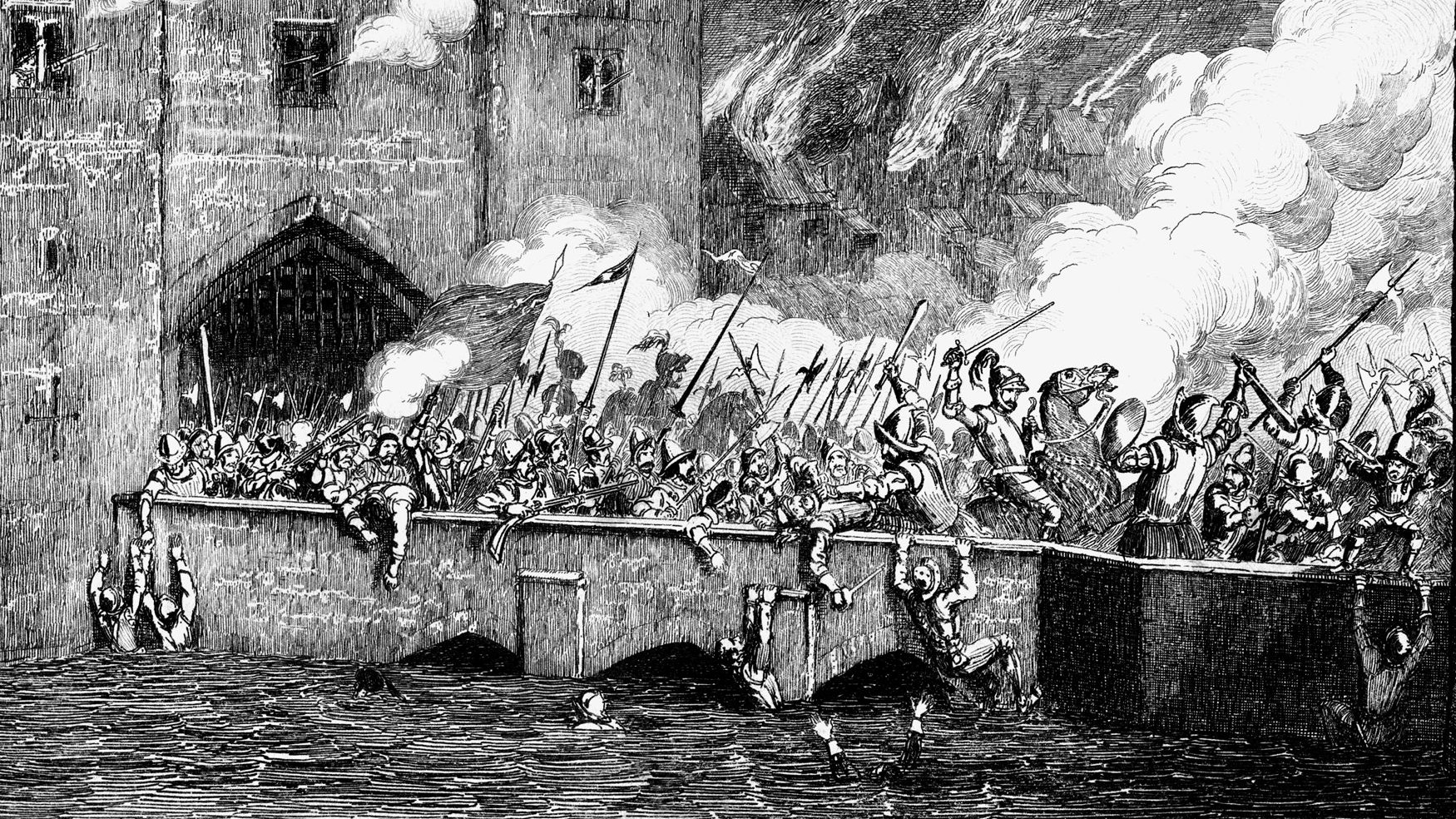

The trenches of Western Europe saw a tremendous number of head wounds on each side, so designers on both sides of the lines rushed various “devices” into production to protect the frontline soldiers. As the story goes, one French soldier was saved by wearing a soup bowl on his head; thus the idea of a steel helmet was born, although various sources suggest that a German steel helmet was already in the design stage to replace the leather picklehaube, or spiked helmet. By the middle of 1916, the first steel helmets began to show up on both sides of the lines.

The French “Adrian” helmet, which bears a resemblance to their firefighter headgear, was issued in large numbers to Russian brigades serving on the Western Front. The French had decorated their headgear with distinctive badges for various units and the Russians were supplied helmets depticting the Romanov double-headed eagle.

As the war continued the Russians began to produce their own domestic version of the Adrian helmet, designated the Model 1916 or M16. This helmet bears the basic silhouette of an Adrian helmet but with a less-defined ventilation comb running over the dome. The M16 was also issued to troops without badges or any formal type of unit identification—although during the Russian Civil War, individual troops may have painted red stars or other decorations on their own helmets.

After the victory of the Communists, the new Soviet government began a swift reorganization of the military, and during this time existing Adrian helmets were reissued with a new Soviet red star front badge to replace the Romanov eagle. The era between the wars saw numerous experiments with various helmets. Few examples of these survive, however, and those that show up on auction sites on the Internet or at military shows should be looked at with some skepticism. Among the most interesting pieces to come out of this period is a German-looking helmet that was eventually discarded completely for the more elegant Model 1936 helmet. Even in hindsight the M36 seems to be a logical transition between the Adrian and M16 helmets of the World War I and the eventual M40 combat helmet.

With a long brim, flared sides, and a comb on the top to allow for ventilation while also serving to deflect “saber” blows, the M36 has a strong Russian look to it and was in service up until the invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941. It was, however, already being phased out by the helmet that would serve the Soviets and their postwar Warsaw Pact Allies for years to come.

Influences on the American Helmet

As with the other powers, America entered World War I without adequate protection. American military planners had hoped to evaluate the various helmets being used, but with time pressing and the need to supply the men, the Americans eventually accepted several hundred thousand British Mark I helmets and then began to produce this version domestically. Although similar in basic shape and with a comparable liner system, the American-produced and British-produced helmets are not identical. Even today it is common to see British helmets from World War I and even World War II passed off as American “tin hats.” There are numerous key differences that are discussed at length in Chris Armold’s book Steel Pots: The History of America’s Steel Combat Helmet.

Use of foreign helmets during WWI was not limited to those of British design. African-Americans who served in the all-black 93rd Division were supplied with French Adrian helmets, and a silhouette of the helmet became the official insignia for the division. Additionally, American volunteer ambulance drivers also used the Adrian helmets with a special badge.

As within the Soviet Union, American military planners experimented with an array of designs to protect their soldiers in future conflicts. Various influences, including the German M16/18 helmets, were taken into account and many of the designs from this period have an almost “medieval” quality to them, with visors and even faceplates. The advent of mobilized warfare was the catalyst of the final wave of helmet experimentation in the 1930s as designers attempted to create protective headgear that could be used by a wide variety of troops while also providing radio communication.

In the end, the American version of the Mark I was still in widespread use when the United States entered World War II in December of 1941. By this time, however, a new helmet was about to be produced, and like the Soviet’s new helmet, it would also remain in use throughout most of the Cold War.

The Soviet SSh-39/SSh-40 and American M1 helmets

By the late 1930s it was apparent in the military circles of both Moscow and Washington that war was inevitable, and each nation developed a helmet that would serve its men for many years. The Soviets simplified the design of the helmet over the years, explains author and Soviet helmet collector Robert W. Clawson, and adds, “The design team created a new experimental model every year until 1939 when they made the model 1939 shell.”

Clawson, author of the recently published book Russian Helmets: From Kaska to Stalshlyem 1916-2001, adds that this basic shell would be used from 1939 until 1969 with few changes. “That shell was used on every helmet from the SSh-39 to the SSh-60, SSh meaning Stalshylem or steel hat.”

The SSh-39 was more streamlined, the designers having done away with the comb and vent hole, while the visor and side flares were significantly reduced. The helmet would, however, go through one last major change before war came—the original liner system that was constructed as a wraparound piece of padded cloth was replaced by a three-pad system that allowed for more precise fitting and reduced the production process. While it was not uncommon for soldiers to paint red stars, unit numbers, or other symbols on the front of their helmets, this practice was not encouraged and examples today are considered very rare.

The first American troops to see action in World War II fought with an updated version of the World War I helmet. This was in use in the Philippines and on Wake Island at the start of the war as the new and improved M1 helmet was just beginning its production phase. This new helmet proved to be a true piece of American ingenuity, the first modern helmet that was designed as a two-piece system where the suspension system (or liner) was to be constructed of a lightweight material while the protective steel shell would be worn over it.

Unlike the Soviet’s SSh-40, which was to remain largely unchanged throughout the war, the American M1 went through several minor design modifications during the conflict. This has in turn led to numerous “variations” that have since become highly sought after by collectors. The most notable is that the early chinstrap loops were welded onto the shell in a fixed position. This was replaced in 1943 with a hinged loop that was less prone to breaking and could also be bent over the internal liner to help keep it in place. This hinged loop would be seen on all M1 helmets to follow—but it has also led to confusion over the years with collectors.

Many had believed that the hinged system was not introduced until after the war, and that period American helmets did not have the hinged loops. Numerous sources, including Chris Armold, stated otherwise, and it is the opinion of this author that loops with hinges were used during the war.

The other notable improvements were not in the shells but with the liner systems, which went through a variety of changes and updates. It is highly recommended that novice collectors consult various sources, including Armold’s books, to get a better understanding of the wartime and postwar liner systems, because these continued to evolve throughout the life of the M1 helmet. Also noteworthy is the specially designed paratrooper liner system that was used in World War II—not only are these highly sought after by collectors but interest after recent movies, and miniseries like HBO’s Band of Brothers, has resulted in a cottage industry producing reproductions and restored pieces that are often passed off as the real thing.

Even original M1 helmets often ended up being reused following the war, and for many collectors this has been a reason to stay away from them. “Original WWII helmets were often over-painted and may have newer liners,” explains Jukka Juutilainen, a Finnish collector of helmets used around the world. He admits he found American and Soviet pieces a little easier on the wallet than German helmets, but also increasingly difficult to uncover. “Real WWII condition helmets are harder to find as collector interest is rising and helmets are decreasing from the market,” he says.

Helmets During the Cold War

When the smoke cleared from World War II the threat of another war was already in the air, and soon two alliances would be facing off against each other in a series of arms races and minor conflicts around the globe. Throughout the next 50 years the basic shape of the two classic helmets of the superpowers would be seen time and time again. Either or both of these helmets would appear in use in Korea, Vietnam, and Afghanistan. “It certainly is fair to call the Soviet model 1940 (or SSh-40) the definitive counterpart to the American M1,” says Clawson.

Many of the Warsaw Pact and even Asian nations in the Soviet sphere of influence eventually adopted SSh-40 helmets. Even the nations that didn’t entirely rely on the Soviet helmets did use them for brief periods at one time or another. The most notable exceptions were Romania, which relied on an updated version of its World War II helmet; and East Germany, which eventually adopted a World War II experimental helmet as its own. The Czechs and Hungarians did use the basic SSh-40 shells but with a different liner system. These helmets have become quite common today and are often sold as “Soviet” helmets, although they were in fact produced and used in Czechoslovakia. The Czech M-53 liner is closer in appearance to the German World War II liner, while the rivet placement on the exterior of the shell is higher up. From a distance or in a photograph it is difficult to tell them apart and Czech M-53 helmets have appeared occasionally in films as Soviet helmets, but none with this rivet placement or liner configuration were ever used during World War II.

Most of America’s European Allies retained their helmets in the years following WWII but this gradually changed with Holland, Italy, and even Germany using an updated M1 at various times. A German version had its own liner system fixed into the helmet with a single weld at the top of the crown, replacing the removable liner piece. Other NATO members continued to rely on a universal two-piece system, and examples of these can commonly be found on Internet auction sites and in military surplus stores.

Many oversea Allies in Asia quickly adopted the American M1 helmet, and the shape of the helmet clearly influenced later domestic helmet design in a number of nations. The SSh-40 and subsequently the SSh-60 (but not the Czech M-53), with an improved liner, as well as the M1, were used in numerous conflicts in the Middle East. And because America had supplied nations, including Egypt, with the M1 before the Soviet’s countering of America’s support of Israel, it was not uncommon to see soldiers on both sides of the line in some of the region’s conflicts wearing American helmets.

As the Cold War dragged on it became apparent to each side that the helmets designed for use in World War II wouldn’t be ideal if a third world war broke out. The time had come to replace these steel shells that had all but become symbols of the Cold War. By the middle of the 1980s modern Kevlar helmet systems replaced the steel pots and remain in effective service in both the American and post-Soviet Russian armies. In various Third World nations around the world, however, the M1 and SSh-60 and later SSh-68 helmets remain on active duty for the foreseeable future. In the 1991 Gulf War, American troops with the new Kevlar helmets faced Iraqi soldiers with their own Kevlar helmets that had the basic shape and outline of the M1.

Collecting Helmets of the Superpowers

Interestingly, during the height of the Cold War there was actually little interest in collecting American helmets, and it was almost impossible to obtain a Soviet helmet from any era. A few World War II-era Soviet pieces did manage to make it to the West but even a Czech-produced SSh-40 with M53 liner system would have cost hundreds of dollars—and this was at a time when a decent German World War II helmet might have cost far less. That all changed with the fall of the Berlin Wall and the end of the Soviet hold on Eastern Europe.

By the mid-1990s modern Soviet equipment was readily available and their steel helmets—or at least the Czech variety—were available for under $30. “Before the fall of the Iron Curtain authentic Soviet helmets were almost impossible to obtain,” says Clawson, who had attempted to collect Soviet items for the past 25 years and says their loss is his gain. “They were extremely expensive. Getting a real Soviet helmet was about as easy as getting a real Soviet submarine,” he says.

He adds that his first helmet, bought 25 years ago and with a red star painted on it, turned out to be a Czech M53, the type that sells daily on auction sites like eBay. But not all Soviet helmets have fallen in price, and original SSh-40s with stamps indicating they were actually made during the war can catch top dollar. Buyers must beware, however, as Clawson admits there is a thriving cottage industry in Central Europe that changes 1948 helmets into 1943 ones with ink solvent.

There are also other “fakes” to watch out for, including French Adrian helmets that are filled with fake Tsarist Romanov eagles, or complete fantasy items like the French M26s with the same eagle—a helmet that was never used. Fortunately for collectors the number of fakes isn’t as bad as with other helmets, especially German World War II pieces, and according to Clawson much of the fakery “is laughable,” and collectors should watch for items that “are usually too good to be true.”

The same holds true for American helmets. “The state of fakes isn’t as bad as with German helmets … not yet,” explains author Chris Armold. “Ten years ago in the area of U.S. helmets only three items were routinely faked: USMC WWII helmet covers and M1C and M2 airborne helmets. That has certainly changed.”

A cottage industry has been born in which helmets are “restored,” and unfortunately often resold as the real deal. But Armold adds that “most fakes are easy to identify if a collector has done his or her homework.” In addition to outright fakes, collectors also need to be wary of NATO items, including 1960s-era Belgian liners that are passed off as original World War II items.

Armold advises collectors to be especially wary of rare items, some of which are harder to find than rare German items. One example is that real American airborne helmets are actually far rarer than any German World War II Fallschirmjager (paratrooper) helmet. Collectors who really desire such a piece should try to go directly to the source and acquire it from a veteran if at all possible.

Additionally, Armold, as well as other advanced collectors, agree that given the state of the copies for extremely rare pieces, a modern restored copy (sold as a copy) might be an ideal alternative. “Spend a few hundred dollars on a nicely done reproduction and fill the hole in the collection. You will never regret doing this and your wallet will thank you for it.”

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments