By Nathan N. Prefer

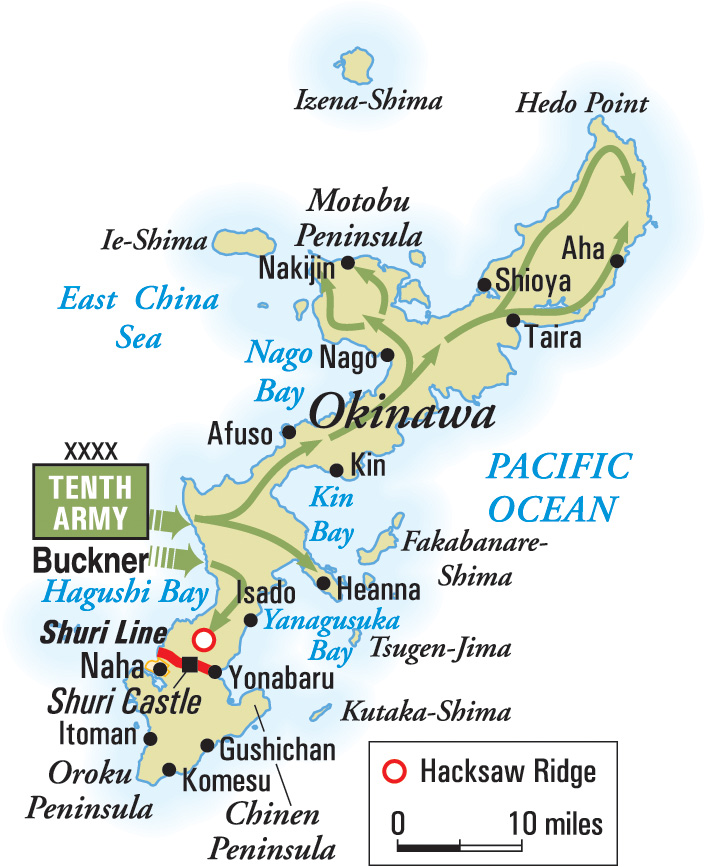

It was called the Maeda Escarpment, after the nearest native village. An escarpment, according to the dictionary, is “a steep slope in front of a fortification” or “a long cliff.” The Maeda Escarpment was both. The American GIs who faced it had their own names, including “Hacksaw Ridge,” “Sawtooth,” and “that big son of a bitch.” If the Japanese had a name for it, it is lost to history.

Hacksaw Ridge, a 500-foot-high plateau, is in southern Okinawa. The plateau on top stretched about 4,200 yards from east to west. Its face was a crest consisting of a sheer rock wall that could only be scaled with ladders or special climbing gear. The entire mass was covered with narrow, jagged ribbons of rock and completely zeroed in by Japanese guns. To the east the ridge ended with a gigantic sentinel-like monolith known as “Needle Rock” to the GIs. Further east are Hill 150 and Hill 152, also called Conical Hill and Kochi Ridge. To the west was a Japanese defense consisting of a score of small individual positions hidden within a maze of low coral and limestone ridges known on U.S. maps as “Item Pocket.” All these formed an anchor to a Japanese zone of defense, a part of their second line of defense protecting southern Okinawa.

What remained unknown until later in the battle was that Hacksaw was defend-ed by thousands of heavily armed Japanese troops hidden deep within its recesses. In effect, Hacksaw was an enormous underground fortress called by some historians an “underground battleship.” Within Hacksaw was a vast cave system, some of them large enough to hold hundreds of men at one time. Passageways connected the caves to each other and to the top of the ridge. Throughout were hidden gun ports and firing positions hollowed out by the Japanese. Even in the village behind the ridge, at Maeda, the Japanese had converted its concrete buildings into fortified bunkers. And behind that were Japanese artillery, mortars, and machine-gun emplacements, all of which had direct access to Hacksaw.

The GIs coming up to this ridge were from the 96th Infantry “Deadeyes” Division. Activated August 15, 1942, the division had trained at Fort Lewis, Washington, before sailing to Hawaii in July 1944. After more training, the division had assaulted Leyte, Philippines, and fought throughout that campaign. In late March 1945, the division sailed for Okinawa, where it stormed the island as a part of the Tenth U. S. Army on April 1, 1945. Under Major General James L. Bradley, it had fought its way down the west coast of Okinawa, clearing Cactus Ridge and Kakazu Ridge and fighting off a major Japanese counterattack. After being relieved by the 27th Infantry Division at Kakazu Ridge, the “Deadeyes” returned to battle at Nishibaru Ridge and Tombstone Ridge before coming up against Hacksaw.

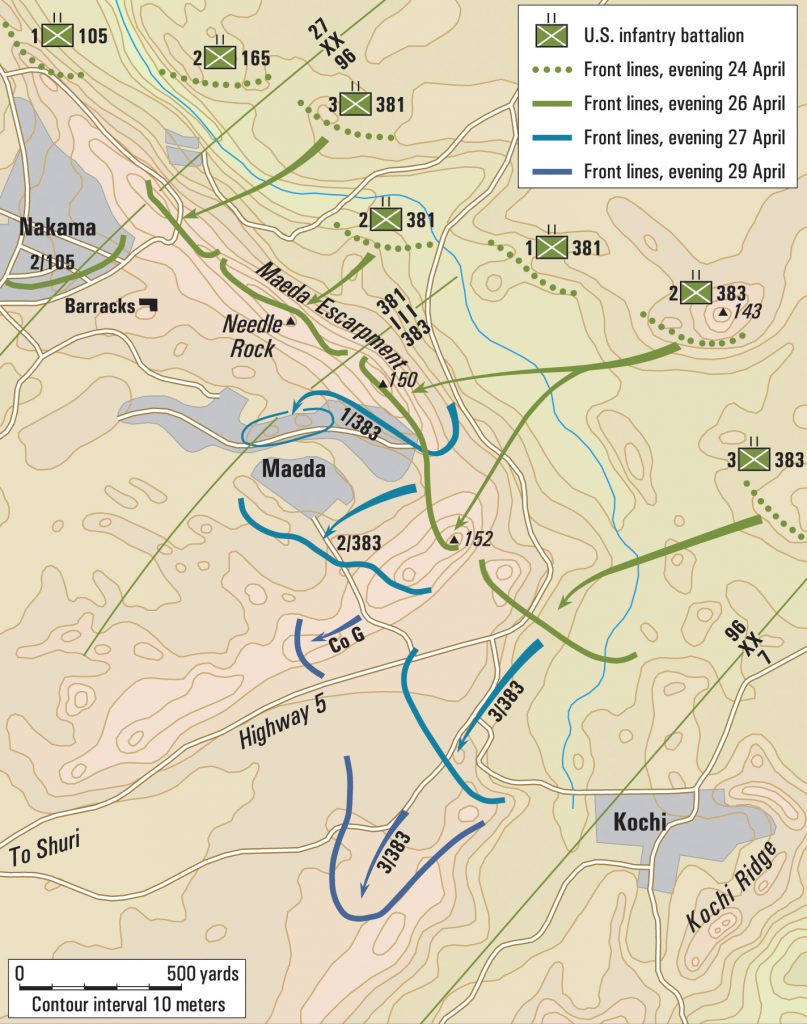

The first steps were deceptively straightforward. Brigadier General Claudius M. Easley, the assistant division commander who had been with the division since activation, took one look at what the troops would soon be calling “Sawtooth” and ordered a heavy artillery barrage against it on April 25, followed by close-air-support bombardment. More than 1,600 rounds of artillery and thousands of tons of bombs fell on the ridge. Then self-propelled cannon of Colonel Michael E. Halloran’s 381st Infantry’s Cannon Company pulled up and fired at every suspected enemy gun position hidden within the ridge.

On April 26, 1945, Company G, 381st Infantry, approached Hacksaw against no opposition until it climbed to the top and attacked a large concrete pillbox, where it suffered 18 casualties in as many minutes. The Japanese, using the reverse slope defense at which they were so adept, stopped the advance. To the east at Needle Rock, Company F tried to get men atop the escarpment, but the first three to reach the top were killed by machine-gun fire.

Company E attacked from Needle Rock and managed to get up the slope before coming under fire. A heavy machine gun, supported by mortars and small arms, covered the advance of three men who managed to get within hand grenade range of the enemy. Pfc William Reeder, a former professional baseball player, spotted Japanese mortars and proceeded to throw an entire box of grenades with World Series accuracy, knocking out most of the enemy guns. The Japanese immediately launched a counterattack, but Staff Sergeant Lee E. Moore, normally a flamethrower operator, grabbed a Browning Automatic Rifle (BAR) and stood up to meet the oncoming enemy. Firing from the hip, he halted the attack and then climbed to the top of Needle Rock and fired down on the remaining Japanese. Eventually, fire from a nearby cave position made him withdraw. However, Sergeant Moore soon returned with his flamethrower and a box of grenades and attacked the cave, eliminating the enemy position and earning a Distinguished Service Cross.

At Hills 150 and 152, men of Colonel Edwin T. May’s 383rd Infantry Regiment reached the tops of the hills only to discover that the area “was alive” with Japanese beyond the high ground. Officers estimated that they could see upwards of 600 enemy troops out in the open, highly unusual for the Japanese on Okinawa. Immediately, the GIs opened fire with machine guns, BARs, and rifles. This allowed tanks and armored flamethrowers to approach Maeda Village and blast the entrenched Japanese. Scores of defenders were caught fleeing from their burning defenses.

This success disturbed Lieutenant General Mitsuru Ushijima, commanding the Japanese 32nd Army. He ordered his 62nd Division to immediately dispatch all reserves to the Maeda area, repulse the American advance, and prevent a repetition of their success. The adjacent 24th Division was to cooperate and provide additional troops if necessary. Clearly, the Japanese intended to hold Maeda.

The “Deadeyes” renewed their attack on April 27 when the 1st Battalion, 381st Infantry, managed to get some men between Hills 150 and 152, supported by tanks of the 763rd Tank Battalion and flame-throwing tanks of the 713th Tank Battalion. For hours, the GIs and their supporting tanks blasted and burned the enemy defenses, forcing many Japanese into the open, where they were cut down by the infantry. But as they approached Maeda village again, the infantry was halted by heavy enemy fire.

Meanwhile, Companies F and G had tried but failed to reduce the large pillbox atop the escarpment. The day’s advance was limited to a slight penetration between Hills 150 and 152. By this time the Americans were aware, after their previous experience at Kakuzu Ridge, that artillery fire against the dug-in Japanese was usually useless except for morale purposes.

Company E, 381st Infantry, also had moved forward as ordered by General Easley, to a position near the western edge of Maeda village. They reached the designated hill without trouble, but no sooner had they arrived than Hacksaw erupted with flame as a dozen enemy machine guns opened fire on the company. Captain George M. Wilcox, Jr., the company commander, found his men pinned down by machine guns, mortars and artillery as they tried to evade the enemy guns. Two men were killed and seven others wounded before a smoke screen covered the company’s withdrawal.

Captain Willard G. Bollinger, commanding Company F, sent two men, Pfc. Alvin Brewer and Pfc. Gordon W. Lundman, to lie just at the crest to prevent enemy infiltrators during the night. The two men were soon fighting off 50 Japanese who were trying to get past Company F. For hours the two tossed or rolled grenades down on the enemy, killing at least 22 of them. Company F lost one killed and 15 wounded during the night. One observer noted that it was like the Western movies, as the protagonists ducked behind boulders and moved from rock to rock while firing at the enemy. So close did this battle become that before long grenades, knives, entrenching tools, and even sharp coral was being used in hand-to-hand combat.

April 27 also produced the first useful intelligence about Hacksaw. A company commander in the 381st Infantry Regiment, Captain Louis Reuter, Jr., and two enlisted men found an empty cave on the northern face of the escarpment and entered it gingerly. They moved deeper into the cave without finding anything. Soon a light from above brought them to a path that led to three other levels below where they stood. Japanese voices could be heard, but no enemy was seen. Backing out toward their original cave entrance, they found a tunnel leading off in another direction. Following this tunnel, they were soon in an observation post within the escarpment; it was equipped with binoculars and a telescope. Looking through the telescope, Captain Reuter was amazed to see everything his division had already cleared, completely back to the original landing beaches. It was now clear that the interior of the escarpment was a rabbit’s den of defensive fortifications and observation posts from which the Japanese could see everything the Americans did for miles around. It was also clear that no amount of artillery or bombing was going to destroy this fortress. As one wounded soldier put it, “We were squatting right on the lid of a vast fortress and didn’t know it.” Captain Reuter received a Silver Star.

American intelligence now understood that the Japanese defense was built around concentric circles of fortifications. Each was intended to halt the enemy advance for as long as possible, allowing the increasingly severe Kamikaze raids to cripple the supporting American fleet offshore. Hopefully, if the fleet could be forced to withdraw, then Okinawa might yet be saved, and the inevitable invasion of Japan postponed. Hacksaw was a key defensive position in the Shuri Line.

The following day, April 28, Company K, 381st Infantry, moved through the zone of the neighboring 27th Infantry Division to attack a large concrete school building known as the “Apartment House.” This was located south of the escarpment and was a center of Japanese resistance. First Lieutenant Albert Strand, a former insurance salesman from South Dakota, led the company. Within moments, Company K was reduced to 24 survivors. So decimated were the companies of the 381st Infantry Regiment that Companies K and I were combined into one, numbering in total 70 officers and men, less than half a full-strength company.

April 29 saw the Japanese strike back with counterattacks all along the 96th Infantry Division’s front line. Major George E. Bucklin’s 2nd Battalion, 383rd Infantry, was hit by Japanese using grenades and spears. One platoon of 30 GIs had only nine still on their feet when the fight was over. More than 250 enemy dead were later counted in this area. Once again, tanks and flamethrowers came forward and repulsed further attacks.

Company L of the 383rd Infantry attacked Hill 138. Fighting was furious and often hand-to-hand. One Japanese machine gun dominated the crest of the hill and repulsed all attempts to knock it out. Finally, Pfc. Gabriel Chavez rushed it with a grenade and blew up the gun, the crew, and himself in one final effort. He was awarded a posthumous Distinguished Service Cross. Tanks managed to crawl to the top of the hill and began a duel with Japanese 47mm antitank guns to the south. For the first time in the month-old campaign, American guns fired directly on Shuri Castle, believed to be the enemy headquarters on Okinawa.

Captain Bollinger of Company F was frustrated. His men found it nearly impossible to dig foxholes in the hard coral. Yet, he knew the Japanese would counterattack that night. Deciding to be creative, he ordered his men to get on top of the boulders instead of digging in below them. Sure enough, the Japanese attack that night was cut to pieces when they charged the empty foxholes while the Americans above cut them down. Captain Bollinger received a Silver Star.

By the end of April, the 381st Infantry Regiment was down to skeleton strength. The entire 96th Infantry Division was exhausted and forced to deploy fresh replacements directly into frontline foxholes. Then relief came in the form of the 77th “Statute of Liberty” Division.

The 77th Infantry Division was a New York-based Army Reserve unit filled out with draftees and volunteers. It had been activated at Fort Jackson, South Carolina, on March 25, 1942, and trained at the Desert Training Center in California before shipping overseas to Hawaii. It was assigned to the III Amphibious Corps and assaulted Guam in July 1944. After this battle, it was en route to Hawaii for rest and reorganization when an urgent call from General Douglas MacArthur reversed its course to Leyte, Philippine Islands. The division landed behind Japanese lines at Ormoc and speeded the end of that campaign. From Leyte, the division was assigned to the Okinawa operation and landed on Yakabi Shima and Zamami Shima before the main landings of April 1. Later it would land on Ie Shima before coming ashore on Okinawa and relieving the 96th Division at Hacksaw.

After three days “mopping-up” on Ie Shima, the 77th Infantry Division was ordered to land on Okinawa and support the advance south. Brigadier General Ray L. Burnell, the division’s artillery commander, led an advance party to the XXIV Corps and the 96th Infantry Division’s command posts to learn all that he could about their new mission. The division commander, Major General Andrew D. Bruce, brought the rest of the division ashore on April 27 and began moving to the front lines. The first to face “Hacksaw” was the 307th Infantry Regimental Combat Team.

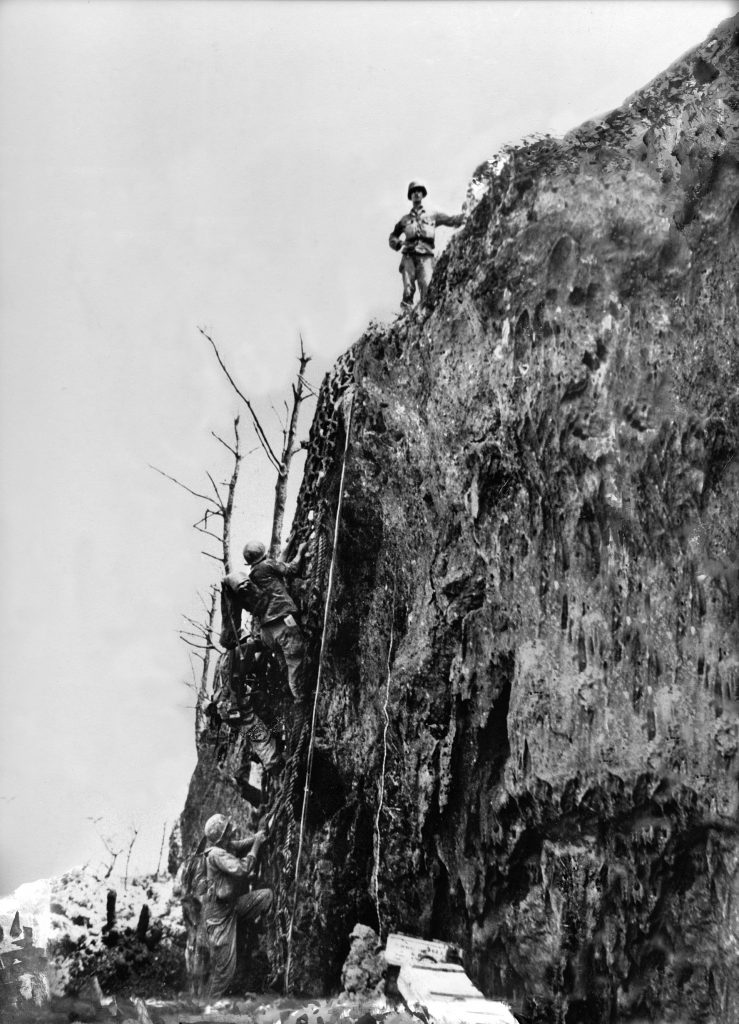

Lieutenant Colonel Gerald D. Cooney’s 1st Battalion, 307th Infantry, began its attack on April 29 when Companies A and B used scaling ladders to get atop the cliff. Once on top, they could see much of the plateau but at first no enemy soldiers. Almost immediately, Japanese troops hidden below ground and in pillboxes opened fire with grenades, machine guns and mortars. A group of small, cleverly camouflaged concrete and steel pillboxes dominated the plateau. These were protected by deadly fire from Japanese artillery, heavy mortars and antitank guns positioned behind the escarpment. When it got dark, Japanese soldiers came out of hiding and sniped at the Americans with rifles and grenades.

The 3rd Battalion, 307th Infantry, could not even get atop the cliff. When Companies K and L tried, they were forced back by heavy fire that came from enemy positions on the reverse slope of the hilltop and pillboxes on the plateau.

The next day, April 30, Company B managed to blow the roof off one of the three larger pillboxes on the plateau. Under cover of mortar fire, a demolitions man dragged a heavy satchel charge along the edge of the cliff until he came to the pillbox. Then he crawled up to the top of the plateau and tossed the charge into the pillbox, blowing off the concrete top. Grenades were used to complete the destruction.

For days the struggle continued. Getting food, water and ammunition to those atop the escarpment was difficult, requiring a climb from the base to the top, some 300 yards, at a 30-degree angle. The evacuation of casualties was equally difficult. On May 1, the division put up four 50-foot ladders and five cargo nets during the night to facilitate the necessary repeated climbs up and down the cliff face. Despite this, no progress was made, and Companies A and B remained stuck along the top of the cliff edge.

By May 7, a gasoline ditch had been constructed, allowing the GIs to burn out some of the enemy positions. But attempts to put this into action were repeatedly foiled by the Japanese. Finally, one squad managed to assemble among a group of scattered rocks and prepared to move against the pillboxes. The first man to stand was wounded in the leg. Mortar shells and machine-gun fire pinned down the squad while enemy riflemen sniped at them. Within seconds, two men had been killed and two others wounded. The squad evacuated its wounded and another squad soon took its place, with no better results. At the end of the day, the two companies atop the escarpment held a shallow bridgehead under cover of coral rocks and boulders with a 40-foot cliff at their backs.

That night the Japanese counterattacked. They penetrated the Company B area, separating one platoon and establishing a flanking position from which they could fire at the company along the cliff edge. Mortars and grenades showered among the GIs, and it was soon apparent that they could not hold their position. American soldiers groped along the cliff edge seeking the ropes and slid down the 40-foot cliff. Others fell or jumped over the edge. A few Company B men managed to get to Company A, where they joined that defense. It was an ugly fight in the dark. GIs at the cliff base tossed grenades at the Japanese, but they had to be careful that those grenades didn’t roll back on them. The Japanese dropped grenades down on the Americans and used their mortars, as well. It was only when the 60mm mortars of Company B found their targets that the Japanese withdrew.

Meanwhile, the 3rd Battalion, 307th Infantry, had tried the same flanking maneuver as had the “Deadeyes.” The battalion moved through the 27th Infantry Division on the right and got behind the escarpment, reaching the “Barracks.” They found the building undefended but under such intense fire that it was safer to dig in just short of the building. The 2nd Battalion, 307th Infantry, followed and dug in alongside. Companies E and F managed to maneuver past the “Barracks,” but heavy fire from the escarpment soon drove them back. At noon, a Japanese mortar shell detonated the 2nd Battalion’s ammunition dump, killing five and disrupting the supply line for several hours. Colonel Stephen S. Hamilton, commanding the 307th Infantry, set up his observation post in the front lines and directed the operations of his battalions. But little could be done under such intense and accurate enemy fire.

On May 2, it was decided to withdraw Company B from the clifftop. The idea was to bombard it once again with heavy 4.2-inch chemical mortars and battalion mortars. More than 200 shells hit the clifftop, sealing six caves at the cliff face. Tanks blasted any enemy position they could identify along the bottom of the cliff, and self-propelled 75mm and 105mm cannon were brought up to do the same. One cave was blasted with six phosphorus shells. As the GIs watched, white smoke suddenly began drifting from 30 other concealed openings along the ridge.

Patrols were busy this day, as well. Some managed to gain the top of the escarpment and even reach the south side, where they discovered more caves and pillboxes. One even managed to sneak up on one of these emplacements and kill the half dozen occupants without loss. This patrol then organized a skirmish line formed with two BAR men on each flank, two riflemen in the center, and two others with demolition charges, and then slipped back to the lip of the cliff, throwing their grenades and satchel charges at any enemy position they encountered. Once out of ammunition, they “ran like hell” back to safety.

May 2 was also the day that Pfc. Desmond Doss, a 1st Battalion, 307th Infantry, medical aid man began a series of acts that would earn him a Medal of Honor. When the battalion withdrew from the clifftop, American wounded were still there. Refusing to withdraw with his company, and despite artillery, mortar and machine-gun fire, Pfc. Doss, the only surviving aid man in Company B, was alone atop the escarpment. He refused to take cover and remained in the target area for hours, treating the wounded and dragging them one-by-one to the edge of the cliff and then lowering them to GIs below, saving 75 wounded Americans. The following day he ran 200 yards into enemy-controlled territory to rescue another wounded man on top of the escarpment. A few days later he saw four men cut down while trying to knock out an enemy cave. Despite intense enemy fire, he treated their wounds and then made four separate trips to bring them to safety. The next day, he treated a wounded officer under enemy artillery fire and stayed with him until it was safe to evacuate. Later that same day, Doss saw a man fall in front of another cave. He raced to him, tended his wounds, and then carried him under enemy fire 100 yards to safety.

During a night attack on May 2, Doss was wounded while dangerously moving about to treat others. He bandaged his own injuries and waited five hours in the darkness until a litter team arrived. While being carried to the aid station, the group came upon another wounded man. Doss insisted on rolling off his stretcher and having the other man carried to safety. He was again wounded while awaiting the return of the litter party. He treated the compound fracture of his arm using a discarded rifle stock. Then he crawled more than 300 yards over rough terrain to the aid station. Doss, a conscientious objector from Lynchburg, Virginia, became a symbol for bravery throughout the 77th Division.

Hacksaw remained defiant. No amount of bravery, heavy artillery, or bombs seemed able to eliminate it. But the GIs kept coming. Company I managed to get to the left-rear of the escarpment and began the deadly process of cleaning out caves and pillboxes on the slopes. One of these caves was found to be three stories deep. A demolition charge thrown into the cave mouth blew out the floor, uncovering the second and then the third level. Two more charges and 25 gallons of gasoline finished this cave.

The GIs of Company F, 2nd Battalion, 307th Infantry, were able to move past the “Barracks” and partially cut off the end of Hacksaw from the rear. Atop the escarpment the 1st Battalion fought hand-to-hand with the Japanese. Company B became involved in a hand-grenade duel in which the GIs tossed grenades as fast as the human supply chain could bring them forward. After several bloody hours, the top of the escarpment was cleared, and the grenade duel moved to the reverse slope. It was a frustrating business. Constantly pounded by grenades and mortars, neither side really had an advantage.

One officer remembered, “The men would come back to the northern side of the ridge weeping and swearing they would not go back into the fight. Yet in five minutes time, those men would be back here tossing grenades as fast as they could pull the pins.”

The center of resistance on the reverse slope was a huge cave that extended back into the ridge for some distance. From this ran numerous shafts and tunnels that opened at other locations along the ridge. One was at least 60 yards long. Despite explosive charge after charge being blown up inside, the shaft never collapsed. Another shaft even had a makeshift elevator. The Americans believed that this shaft held a hospital, a dormitory, and storage for food, water and ammunition. Rather than confirm their suspicions by investigation, the GIs blew the entrance closed.

By the end of May 3, the 307th Infantry Regiment had all but surrounded Hacksaw. The 1st Battalion was atop the ridge, the 2nd Battalion was at the eastern end, and the 3rd Battalion was on the southern slopes of the escarpment. The regiment spent the night of May 3-4 under bombardment from Japanese guns located on the Chinen Peninsula east of Hacksaw and from Shuri to the south. With daylight, the 1st Battalion began to clean up the top of Hacksaw. Armed with cases of grenades, satchel charges, and gasoline raised to the top in ship’s cargo nets, Companies A and C lined up on the edge of Hacksaw and began throwing grenades as fast as possible. After 20 minutes, someone shouted, “Go!” and the two companies started forward, blowing up caves, pillboxes, and shaft openings as they went. Some of the stronger caves even resisted 25-pound satchel charges and had to be destroyed using double charges of explosives. An estimated 600 enemy troops had been killed.

By late afternoon, the top of the ridge was cleared, and the 1st and 2nd battalions had made contact on the far side of Hacksaw. The 1st Battalion, 307th Infantry Regiment, with Companies E and I and the 1st Platoons of Company C and H, had earned themselves a Presidential Unit Citation. It read in part, “For assaulting, capturing and securing The Escarpment, a heavily fortified coral rock fortress which was the key to the famed Japanese Shuri defensive position on Okinawa during the period 30 April to 5 May 1945, and making possible a general advance by all elements of the command.”

The 2nd Battalion, meanwhile, had been clearing the eastern end of Hacksaw. As they did so, a previously unknown Japanese strongpoint opened fire. It took tanks firing into the hill, just underneath the 1st Battalion on top of the ridge, and an infantry attack using explosives to eliminate this new threat. One tank shell must have hit the Japanese ammunition dump: A tremendous explosion inside the cave took the fight out of the Japanese. Companies E and F then continued to work the southern slope and soon made contact with both sister battalions.

The 3rd Battalion had the best day. They were still around the “Barracks” awaiting the arrival of Company I coming alongside. As they waited, the Japanese launched a rare daylight counterattack, hitting Company L. Using a smoke screen as a cover, about a company of Japanese attacked just after daylight, losing 50 of their number to the guns of Company L. Shortly afterward, Company I appeared, having blown up at least 75 enemy caves in the past three days.

Behind the Japanese lines, another battle had been raging. The birthday of the Japanese Emperor had been celebrated on April 29, and this had touched off a fierce debate within the high command of the 32nd Army. General Ushijima’s chief of staff, General Isamu Cho, argued strongly for a decisive action. “We must mount a massive counterattack while we still have the strength!” he insisted. “In a few more weeks, attrition will have eaten away at our forces, and we will be too weak to take the offensive. We must strike now and destroy the Americans, even at the risk of losing our whole army. Better we should die fighting than to keep slipping passively toward sure defeat!”

But the architect of the 32nd Army’s strategy, Lieutenant Colonel Hiromichi Yahara, spoke in favor of a continued defense in depth. He pointed out that it had taken the enemy a month to gain only two kilometers of southern Okinawa and that the 32nd Army had already held out for more than a month, something no other invaded island had been able to accomplish. He reminded the staff of the great losses suffered by the Americans and that a counterattack would certainly fail to break through the American lines with the forces then available to the 32nd Army. Unfortunately, few sided with him, and General Ushijima decided in General Cho’s favor.

General Cho had already spent considerable time on a detailed plan for his counterattack. The 24th Division was to seize the Maeda Escarpment and the town of Maeda, which controlled Highway 5. Then the 44th Brigade would drive west, cutting off the 1st and 6th Marine Divisions. Assisted by the 62nd Division, the 44th Brigade would annihilate the Marines while the 24th Division recaptured the Maeda Escarpment. Meanwhile, other Japanese units would strike at the 7th Infantry Division at Conical Hill and further east. Because he considered Maeda and the Maeda Escarpment the keys to defeating the Americans, General Cho assigned extra infantry and two companies of tanks to that part of the attack. Further, he arranged for a heavy artillery bombardment and even rare air support for the attack on Hacksaw, which was set for May 4. Even if the attack failed, General Cho believed that the Japanese Army would have preserved its honor.

While the Japanese prepared for their grand counterattack, Colonel Cooney’s 1st Battalion, 307th Infantry, was counting its losses. In one 36-hour period, the four-company battalion had gone through eight company commanders, mostly wounded. Arriving at the escarpment with a strength of 800 men, it would leave on May 7 with 324 men. The division estimated that it had killed more than 7,000 enemy troops during the battle.

The Japanese counterattack began as scheduled with infiltration by small groups intended to target American command posts and communications centers. One Japanese infantryman’s diary contained an entry that read, “The time of the attack has finally come. I have my doubts as to whether this all-out offensive will succeed, but I will fight fiercely with the thought in mind that this war for the empire will last 100 years.”

The 32nd Infantry Regiment, supported by tanks and engineers and strong artillery, attacked the 77th Infantry Division at Maeda. Poor roads and American artillery interdiction reduced the armor support to two medium vehicles. One Japanese infantryman complained that the entire march forward was harassed by American artillery and that most of the men in his command were killed or wounded by this fire.

The 3rd Battalion, 32nd Infantry, supported by nine light tanks, struck the 306th Infantry Regiment, 77th Division before dawn on May 4. The Japanese found some weak points in the line, but heavy automatic weapons fire halted any significant penetration of the line. Nowhere did the Japanese break through. Except for driving one platoon off a small hill, success completely evaded the Japanese attackers.

Most of the Japanese light tanks were knocked out by American artillery, and the rest withdrew when their infantry stalled in front of the American defenses. By 7:30 that morning, the 306th Infantry had driven off the Japanese. American artillery and mortars took a heavy toll on the remaining Japanese. A second effort the following night managed to reach the 306th regimental command post, but in the end fared no better. General Cho’s counterattack had failed. The Maeda Escarpment, Hacksaw Ridge, Sawtooth and “that big son-of-a-bitch” would no longer trouble the Tenth U. S. Army in its 82-day struggle to finally secure Okinawa.

Nathan Prefer is the author of several books and articles on World War II. His latest book is titled Leyte 1944, The Soldier’s Battle. He received his Ph.D. in Military History from the City University of New York and is a former Marine Corps Reservist. Dr. Prefer is now retired and resides in Fort Myers, Florida.