By Phil Zimmer

Captain Odd Isaachsen Willoch knew what had to be done. The 55-year-old career Norwegian officer, commander of an aging coastal defense ship, was looking down the five-inch gun barrels and 21-inch torpedo tubes of the Wilhelm Heidkamp, a state-of-the-art German destroyer. Despite the mismatch against his outgunned “old bathtub,” Willoch said, “Man the guns. We are going to fight boys.”

In a determined effort to protect the crucial northern iron ore port of Narvik on April 9, 1940, the 40-year-old outdated and outclassed Eidsvold slowly gathered speed as it moved toward the German flagship that carried both Commodore Friedrich Bonte and Maj. Gen. Eduard Dietl, commanding officer of the invasion troops.

The Germans had proclaimed they came as friends to protect Norway from Britain. Consequently, they initially hesitated to fire on the oncoming vessel, but when the Eidsvold closed to within 1,000 feet, the destroyer unleashed six torpedoes. Three struck the Norwegian vessel, igniting its ammunition magazines. The enormous explosion lit the sky as the ship split in two and quickly sank. Nearly all 181 crew members on board were lost, including Willoch, with only six sailors surviving the ordeal.

The Norge, the Eidsvold’s sister ship, was on patrol closer to the harbor entrance when her crew spotted two other German destroyers through a heavy snow squall. The Norwegians fired five 8.3-inch rounds and five salvos from the starboard 6-inch battery. The German ships of the 1st Destroyer Flotilla were in the process of disembarking the three battalions of the reinforced 139th Mountain Regiment of the 3rd Mountain Division onto the steamship pier at Narvik. Lt. Cmdr. Kurt Rechel ordered the Bernd von Arnim’s 5-inch guns and machine guns into action, and the Germans fired seven torpedoes for good measure against the Norge.

Two torpedoes struck home, one aft and one amidships, causing the Norwegian vessel to capsize to the starboard and sink within minutes. Of the 191 sailors on board, 101 went down with the ship. The combined action at Narvik against the two largest ships in the Norwegian navy was over in a span of some 23 minutes with the loss of 276 sailors’ lives. The Germans sustained no losses in the engagements. Dietl continued offloading his seasick troops from the two destroyers and sought out Colonel Konrad Sundlo, who commanded more than 1,000 Norwegian troops in the Narvik region.

Dietl was more than a match for the 59-year-old Norwegian commander. Like Willoch, Sundlo was a graduate of the Norwegian Military Academy; however, Sundlo was cut of different cloth. He was an associate of pro-Nazi politician Vidkun Quisling and had privately expressed pro-German leanings.

Dietl met the German consul at the pier, and the two set off to find Sundlo. They were accompanied by seven soldiers who followed in a taxi. Sundlo reportedly told the Germans to leave within 30 minutes or they would be fired upon. Dietl, never at a loss for words, reiterated that they were peacefully occupying Norway to protect it from the British. He pointedly mentioned the naval guns trained on the Norwegian positions and noted that a bloodbath would be avoided if the Norwegians put their guns down.

The Germans continued to offload men from three destroyers now in port and set up machine-gun positions on the high ground as the discussions continued. A total of 600 German soldiers were poised to take the town, and they secured key bridges, railway and telegraph stations, and city hall. Reports continued to come in on the German movements as Sundlo surrendered the northern port to Dietl.

Narvik was crucial to the campaign that saw both Norway and Denmark fall under the heels of the first combined land, sea, and air attack in world history. For the most part, the initial German campaign that began on April 9 was exceptionally well executed. Citizens of both countries were stunned by the suddenness of the attack and speed of the German forces. Close-in Denmark fell rather quickly to the Nazi forces, while combined German strikes against six key Norwegian locations required a bit more time, energy, and manpower.

Narvik, a community of about 10,000 people located above the Arctic Circle in northern Norway, was a key target for the iron ore-dependent Germans. German leader Adolf Hitler’s regime needed a steady and reliable supply of high-quality Swedish ore for its wartime industries. The wintertime supply came overland by rail to Narvik where it was transported by ship to Germany’s ever-hungry blast furnaces. The conquest of Norway denied its military facilities to the British and provided airfields for the Luftwaffe and endless miles of protected fjords for the Kriegsmarine and its U-boat fleet. This enabled the Third Reich to range farther into the North Atlantic in the effort to cut off supplies headed to both Great Britain and the Soviet Union.

The events in Norway were to lead to the fall of British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain’s government on May 10, 1940, and the installation of Prime Minister Winston Churchill, who would steady and lead the British through the remainder of the long, bloody war.

The defeat of Norway was effectively achieved on April 9, 1940. By that point, the Germans had control of every major coastal city and the majority of the key military bases. The modern airfields at Oslo and Stavanger also were taken in the combined air, land, and sea assault. It was a coup de main on a national level.

Interestingly, the Allies had plans to land in Norway before the Germans arrived as a preventative war action. Plan R4 called for landings at Narvik, Bergen, and Stavanger with upward of 100,000 British and 50,000 French and other troops to fill out the operation over several weeks. The poorly planned and loosely coordinated Allied landing force was rather idly standing by to act if the Germans violated Norwegian neutrality, or if changing conditions warranted.

The battle for Narvik, in many ways, summed up the misdirected, back-stepping ways of the Allies at the beginning of the war. Sundlo surrendered his 1,000-man force without firing a shot. But Dietl commanded a relatively weak force that had lost much of its war-making matériel in the storm-tossed voyage, and his men were far from home with the powerful British Royal Navy prowling close at hand.

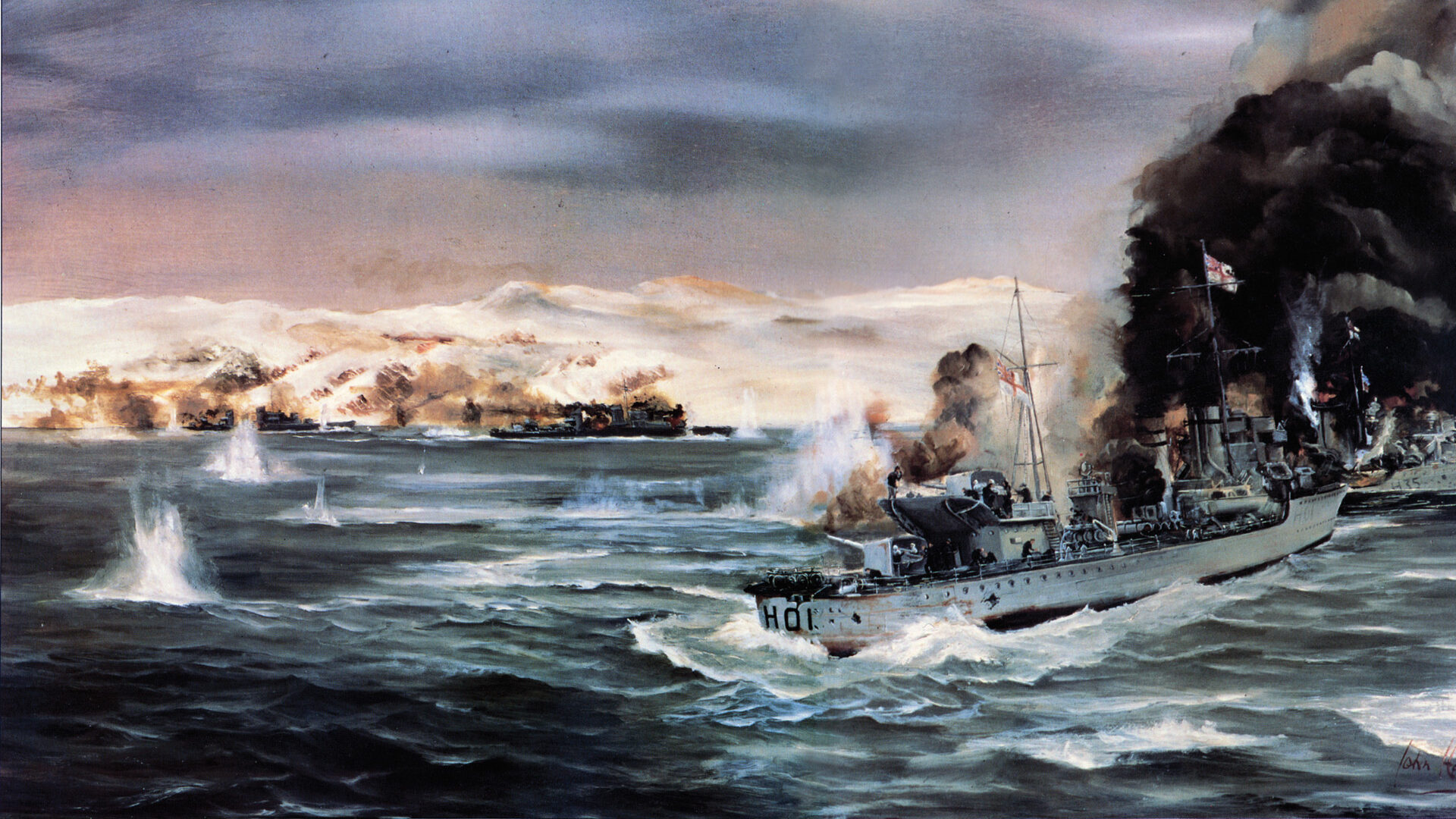

Eventually there were 10 German destroyers at Narvik under Bonte, all awaiting refueling from the long voyage. Meanwhile, Captain Bernard Warburton-Lee, commander of the British 2nd Destroyer Flotilla, which comprised five destroyers, received orders to steam toward the northern port. Four of his vessels were 1934-era destroyers reportedly capable of speeds up to 36 knots and armed with four 4.7-inch guns and eight 21-inch torpedoes. Warburton-Lee decided to attack “at dawn high water” on April 10; dawn for surprise and high water for some protection against mines.

The British vessels inched slowly forward in a snowstorm so fierce that they missed one Norwegian ship, running with full lights, as it passed through the British formation. Hardy, Hunter, and Havock crept slowly into the harbor while Hotspur remained behind to block any German warships arriving from the northwest and Hostile remained nearby in reserve. Five German destroyers were in the harbor, two on either side of the Jan Wellem, being fueled. At 4:30 am the British spotted both the Anton Schmitt and the Wilhelm Heidkamp with the sleeping Bonte on board.

“Get on with it,” said Warburton-Lee, and Hardy launched three torpedoes. The first one hit the bow of the German fuel ship, and the second torpedo struck the aft section of the flagship. The second torpedo ignited the back magazine and set off an explosion that killed Bonte and more than 70 sailors. The third torpedo missed and four other torpedoes from Hardy also missed their target but damaged the ore wharfs before the vessel laid smoke and headed out. Hunter then shot off a round of torpedoes and fired its guns.

One torpedo struck the Anton Schmitt. Havock, the third British ship in line, fired three torpedoes with two striking separate merchant ships, per orders, and striking the Schmitt, which sank in about a minute with the loss of 63 sailors.

The surprised and confused Germans at first believed they were under aerial attack, but gunfire from Hunter in the dark, snow-filled early morning soon brought a returning round of German gunfire. Hostile returned to the main harbor and fired a salvo at the Roeder, striking it twice. The German ship managed to launch eight torpedoes, with several running under the British destroyers. Two other German ships joined the shooting fray but failed to record a hit in this part of the battle.

Warburton-Lee drew off and considered the situation. His vessels were untouched and Hostile still had a complete complement of torpedoes. He briefly considered the prospect of putting a landing party ashore to recapture the city but elected to make another naval run at the German destroyers hemmed in the port. At 6:44 am the six British destroyers formed a line with Hardy in the lead and Hostile at the tail and steamed at 20 knots toward the harbor. The Kunne and Lüdemann took the British ships under fire as they neared the inner harbor entrance. Hostile took a shell that caused little damage. Warburton-Lee ordered his vessels to make for the open sea. They were chased by three German destroyers. At that point, Hardy took several hits, with its bridge destroyed and Warburton-Lee mortally wounded.

Paymaster Lieutenant Geoffrey Stanning, the only man left moving on the bridge, took control of the ship and managed to get it near shore. The crew jumped overboard and began swimming in the icy waters, dragging the wounded captain, who yelled, “Swim, lads, swim!”

The courageous captain soon died, but others were taken in and warmed by local residents. A number of sailors were transported to a local hospital and most of the crew was later evacuated by the destroyer Ivanhoe. Warburton-Lee later received the first Victoria Cross in the war.

The sea battle continued, with Hunter catching fire and losing speed and Hostile encountering steering difficulties. Thiele and Arnim continued to pound away at the British destroyers. As they closed on Hunter, the lead British destroyer, even the German 37mm and 20mm antiaircraft guns opened up. Hunter was pounded with repeated shell hits, its engines stopped, and flames shot skyward. Havock was steaming at 30 knots behind and it sliced into the rear of the hapless Hunter, which eventually sank with the loss of more than 100 sailors.

The two British destroyers at the rear steamed past the two tangled ships and then slowly turned to protect Havock as it worked its way free from Hunter. On the way toward the open sea, the British came upon the Rauenfels, a German ammunition ship heading toward Narvik. The damaged but spunky Havock fired on the German vessel, which ran aground and exploded, sending a column of smoke 3,000-feet into the crisp Norwegian air.

By the end of the engagement, the British had sunk two German destroyers, damaged five others, and sunk eight merchant ships. The damaged port was a strange sight. “German destroyer afire from stem to stern,” recalled a Narvik resident. “Its engines were still operating but it circled aimlessly.” Approximately 130 Germans lost their lives, and only three Nazi ships were undamaged, although they had expended about half their ammunition. The British lost Hunter and 108 men and Hardy with 19 men. Hotspur suffered 20 dead; the other two destroyers did not sustain any losses.

Significantly, the remaining German destroyers stayed trapped in Narvik’s harbor while additional British naval forces steamed to the scene. A British force led by Vice Admiral William Whitworth aboard the battleship Warspite arrived at noon on April 13 to finish up matters started three days earlier by Warburton-Lee. Warspite, which had 15-inch guns, had seen action at the Battle of Jutland in World War I. Supporting Warspite were nine British destroyers. The battles on April 10 and April 13 are known as the First Naval Battle of Narvik and the Second Naval Battle of Narvik, respectively.

This was perhaps the first time the British had wedged such a large vessel into such a relatively narrow fjord, and the daring gamble paid off. They isolated the destroyer Erich Koellner that had been damaged two days earlier. The covering British destroyers overwhelmed the German vessel with torpedo and gunfire, as Warspite opened its large guns and finished it off. The remaining four German destroyers moved to block the British advance into the port, with the Germans firing over the escort vessels in an attempt to strike the huge battleship. The roar of gunfire echoed from the mountains and gorges surrounding the harbor.

As German ammunition ran low around 2 pm, the German destroyers retired to the narrow side fjords only to be hunted down by the advancing British warships. Kunne beached itself and was struck by a British torpedo. Giese and Roeder, both damaged earlier, were then dispatched.

“It is a sight, burning and sinking enemy ships all around us, and our own destroyers search into every little corner that might hide something,” wrote Gunners Mate Daniel Reardon of the Warspite. The Zenker, Arnim, Thiele, and Lüdemann were holed up in the narrow-necked Rombaks Fjord, protected there from the large battleship. The British destroyers moved in as Thiele ran onto the rocks and the crews from the three other damaged German destroyers escaped to shore.

The Second Battle of Narvik was clearly a one-sided victory for the British, although they still had to deal with what they estimated were 2,000 entrenched German troops in Narvik. Ten modern German destroyers, half of that country’s powerful destroyer arm, lay heavily damaged or sunk in the fjords near Narvik. Ironically, though, the loss of the destroyers added to the strength of the German forces there because the estimated 2,500 rescued sailors were used to supplement Dietl’s ground troops.

As Whitworth headed out of Narvik on April 13 aboard the Warspite with its escorting destroyers, he reported to London that German naval strength around Narvik had been crushed and predicted the city could be easily captured without serious German naval opposition. Whitworth might have sent a landing party ashore from his own vessels, but he hesitated because of the relatively small number of troops available and the presence of the highly trained German troops in the Narvik area. Unknown to him, the Germans had believed the naval bombardment from Warspite had signaled the start of an Allied landing and had pulled back to the hills surrounding the town. Once it was clear that there would be no landing at that time, the Germans reoccupied Narvik.

Officials in London were so delighted by the victory that little thought was given to the lost opportunity to put men ashore. Hitler, for his part, flew into a rage and demanded that Dietl quickly depart Narvik and travel southward over extremely harsh cold mountainous terrain to join up with German forces in Trondheim. It was an unrealistic order considering the large Norwegian port lay more than 550 snow-covered miles to the south. Experienced, level-headed German officers intervened and convinced the German leader to keep the forces at Narvik in place for the moment.

Hitler, though, was right about one thing: the German position at Narvik was not strong. Although Dietl had some 4,600 men under him, only 2,000 were combat-ready soldiers, with the remainder being sailors pressed into ground action. In addition, Dietl’s men were desperately short of ammunition and heavy weapons. The presence of the British naval forces and the extreme distances involved meant that there was little realistic expectation of receiving additional war matériel. And to add to the German dilemma, on April 14 two companies of Scots Guards landed at Harstad, just north of Narvik, where they joined up with Norwegian forces there that had not surrendered.

The Germans were faced with other problems as well. For one, they had planned to use their U-boats to provide a protective screen for their surface ships and provide secure communications for the extended operation that ran from Oslo to Narvik. As the British ships funneled into the fjords, the Germans expected rather easy pickings compared to targets in the open sea. But the submarine captains encountered the unexpected; torpedoes either failed to explode or detonated prematurely.

Gunter Prien, the acclaimed captain who had sunk the massive 620-foot battleship Royal Oak with his brazen October 1939 attack at heavily guarded Scapa Flow, reported that his U-47 fired four torpedoes at nearly point-blank range at two transports on April 15. No explosions were recorded so he reloaded and delivered a second attack on the surface at midnight, again without success. One of those torpedoes did run off course and exploded against a cliff, alerting the British to his presence. Prien and his crew narrowly escaped running aground while being pursued with depth charges.

It was well after the Norwegian campaign that the Germans learned the full extent of the problems that bedeviled the torpedoes. Several factors were in play, including a defective action of a striker within the torpedoes, other problems that caused many to run below their targets, and the strong magnetic fields around northern Norway that affected the torpedoes. As it was, the U-boat failures left a considerable gap in German efforts to protect their beleaguered and comparatively isolated troops in Narvik.

By April 16, Hitler was again fretting about the situation, arguing that Dietl’s force either scoot into nearby Sweden or be evacuated by air. Gen. Col. Alfred Jodl stepped into the breech and argued against withdrawal into Sweden, and also noted that evacuation by air was not practical because of the lack of sufficient numbers of long-range aircraft. The very next day, though, Hitler authorized Dietl to move his troops into neutral Sweden to avoid capture. Again the high command worked around Hitler, delaying that message for a period and sending Dietl a congratulatory dispatch along with his promotion to lieutenantgeneral . The accompanying message expressed the high command’s confidence that Dietl would manage “to defend Narvik even against a superior enemy.” Eventually Hitler agreed with Jodl, and a new order was sent advising Dietl to defend Narvik as long as possible.

But Hitler was rattled, nearly to the core, according to some reports. Those who opposed his fervent desire to withdraw Dietl’s troops even had to drag in a Norwegian expert to explain the incredible unreasonableness of expecting Dietl’s forces to traverse the cold, snow-filled mountainous terrain laying between Narvik and Fauske some 120 miles to the south.

The matter settled for the moment, 10 Junkers Ju-52s were sent to reinforce Narvik by air. The planes landed on a nearby lake and unloaded a battery of mountain artillery. Germany pressured Sweden to allow it to reinforce Narvik via the Swedish railway that ran to the port, and the neutral nation eventually agreed to the demand. Food, medical supplies, and more than 200 technicians made their way to Narvik over the Swedish line, and in May more than 800 injured German merchant sailors and wounded servicemen quietly made their way back toward Germany over the same rail lines.

The Germans had been reading the secret British messages and, to compound matters further, British Admiral William Boyle and Maj. Gen. Piers Mackesy differed on how best to take Narvik. Mackesy feared a direct assault against the well-trained German mountain troops and favored an envelopment that itself would not be easy. Two battalions of the German mountain troops were deployed 15 miles north of Narvik, with the third battalion stationed in the town itself. The 2,600 German sailors, armed with Norwegian weapons captured at Elvegaardsmoen, were positioned along Herjangs Fjord to the north of Narvik, along the rail line to Sweden, and in support of the mountain troops in town.

Following considerable discussion, Mackesy agreed to a naval bombardment of Narvik on April 24, with the battleship Warspite leading the attack along with the cruiser Effingham. A fierce, three-hour bombardment apparently did little to shake the defenders, although the attackers could not be overly sure because of high winds and heavy snowfall. Envelopment, rather than a frontal assault, now appeared to be the best way for the Allies to take the besieged town. On the night of April 28-29 French and British troops landed to the north and south of the town as part of the plan.

The Luftwaffe was called upon to continue the supply and reinforcement of the northern town, hinder the advance of the Allied forces that now included Polish and Norwegian troops, attack Allied ships in the area, and support a German overland advance on Narvik. The port was at the far end of a long supply trail from the Fatherland. The British, for a time, had limited air support from carriers in the area and had use of an airfield at Bardufloss, which was located some 27 miles northeast of Narvik. This gave the Allies some air parity with Germany over northern Norway. Approximately 600 local Norwegians helped remove nine feet of snow from the field, and 14 Gladiators arrived on May 14 and a squadron of Hurricanes five days later.

Despite its best efforts, the Luftwaffe could only slow but not stop the British, French, Polish, and Norwegian forces now advancing overland toward the port. By late April, the Allied forces had grown to 27,000 soldiers, who easily outgunned the exhausted and hard-pressed German defenders. The Allies also had 24 artillery guns and five antiaircraft batteries as they moved forward under Lt. Gen. Claude Auchinleck, who had replaced Mackesey.

Despite the presence of British artillery and fighter planes, the Germans managed to drop 650 paratroopers near Narvik between May 23 and May 30. The air drop of May 23 showed how stretched the German forces were with the onset of the campaign in France. The 66 men dropped that day had received a much curtailed, 10-day course in parachuting, although no losses were reported.

The Allied naval forces pulled into the besieged harbor on May 27 and May 28 and let loose a heavy bombardment that started a number of fires. Dietl called for assistance and all available aircraft, including Stukas from an intermediary field at Mosjoen, arrived to attack the force of 10 ships.

Dense fog cloaked the British air base at Bardufloss, giving the Stukas, Ju-88s, and He-111 bombers free rein over the ships and Allied ground positions. The planes “having a clear run, were whirling like angry eagles low over the ground, almost touching tree tops, and sweeping the gray thicket with murderous machine gun fire,” wrote a Polish soldier. “The fall of bombs was short and heavy, like that of ripe apples from a tree.”

Once the fog lifted at Bardufloss, the British fighters were sent aloft and downed two German bombers and destroyed two flying boats on the water. In addition, two Gladiators from the carrier Glorious shot down a floatplane, and two additional bombers were destroyed by British antiaircraft fire.

In the midst of the fierce air attack, the Allied forces took Ankenes just south of Narvik, the French mountain troops thrust southward toward Narvik, and the British navy landed forces on the town’s waterfront. Dietl had seen enough of the determined Allied attack. He skillfully avoided encirclement, pulled his troops back along the rail line toward Sweden, and abandoned most of his heavy equipment in the process.

The next day the Germans added increasing numbers of Bf-110s to the mix, but these were fitted with the “dachshund’s belly,” a long-range fuel tank that made them cumbersome in battle against the faster and more nimble Hurricanes. The Luftwaffe was torn between the need to directly aid the men on the ground versus the need to focus on the British air base at Bardufloss, which was providing deadly fighter coverage over Narvik. It was, in reality, a chicken-and-egg argument that could only have been resolved with more resources than the Germans could muster at that point.

The Germans maintained the view that the Allies would make a final thrust to drive Dietl out of the northern region, thus separating the Third Reich from the valuable, high-quality iron ore that was shipped through Narvik. On May 30, Hitler sent a message that Dietl’s isolated forces were to be supported by all available means. The German commander was to hold on for five or six days so that a relief operation could be mounted. The Luftwaffe, in the meantime, was to protect and support the ground forces. Several desperate ideas were floated, including the use of gliders to transport additional mountain troops to Narvik, and in early June the planners seriously considered parachuting another 1,800 men into the area. But events and already stretched resources prevented the full implementation of such plans, although a few troops were dropped to supplement Dietl’s forces.

Another rather fanciful plan called for 6,000 men and a dozen tanks to be landed nearly 90 miles north of Narvik. They would then move southward to strike behind the Allies’ positions, while the Luftwaffe would strike and take the British airfield at Bardufloss and initiate support operations from there. This was set for the third week of June, but it never came about because the Allies had pulled the plug on their own efforts well before then. That was just as well because the Hurricanes at the well-defended Bardufloss airfield would have presented significant difficulties to the already extended Luftwaffe. Plans were also undertaken with a handpicked force of 2,500 troops to bring in relief from the south along the coast.

When the weather cooperated, the Germans did bring the Allied positions in and around Narvik under intense pressure, causing fires that gutted the center of the town and knocking out communications. But continued poor weather hampered Luftwaffe operations, and the depleted supplies of food and war matériel weighed heavily on Dietl and his men. The besieged Germans were convinced that a final Allied push was on the way.

A surprise source of relief came for the Germans. The Allies, after winning Narvik and pressing Dietl’s men near to the point of surrender, decided to evacuate Narvik as they became concerned by the May 10 German invasion of France and the need for men to defend Great Britain.

It was Churchill who pressed for the return of the troops as the Allies were in the final evacuations of the “Miracle at Dunkirk.” The first 15,000 Allied troops around Narvik were loaded aboard ships between June 4 and June 6, with the rear guard departing on the morning of June 8 aboard the cruiser Southhampton. The troops were covered by escort vessels and the carrier Ark Royal as the bulk of their stores and equipment were also loaded without incident during inclement weather that helped hide the movement from the Germans.

As the skies eventually cleared on June 8, it became evident that the Allies had departed. The Luftwaffe went gunning for the carrier, especially, but only managed to damage a steamer. A German naval force under Admiral Wilhelm Marschall managed to destroy a tanker, an escort trawler, and the unescorted troopship Orama, which was carrying a crew and 100 German prisoners. The Germans picked up 275 survivors and let the hospital ship Atlantis, with more than 600 wounded Allied soldiers onboard, pass unmolested in accordance to the rules of war as they were observed early in World War II.

British land-based fighter planes had covered the evacuation area, and initial plans called for them to be destroyed at the end of the operation. In a daring, last-minute move, the British decided to attempt to land them on the Glorious, which was in the area along with Ark Royal. In the early morning hours of June 8, the pilots managed to get 10 Gladiators and eight Hurricanes safely on deck, despite personally never having attempted carrier landings before and in planes not built for such an operation.

The carrier Glorious, accompanied by two destroyers, was spotted at 4:45 pm and taken under fire by the German battlecruisers Scharnhorst and Gneisenau. Although close to the Norwegian coast, Glorious Captain Guy D’Oyly-Hughes failed to have any patrol craft aloft. The two British destroyers laid smoke and launched torpedoes in a vain effort to ward off the battlecruisers. The carrier’s 4.7-inch guns were no match for its opponents, and at about 6 pm an 11-inch shell from the Scharnhorst hit the carrier’s bridge, killing the captain and destroying the steering mechanism.

The destroyer Ardent turned on the attackers and launched her torpedoes at Gneisenau, which skillfully evaded them. Both German battleships fired on and stuck the plucky Ardent, which capsized and sank within four minutes.

The German vessels then scored additional devastating hits on Glorious, and its deck was penetrated with the ammunition and fuel erupting in fire. She slowly “turned on her side pouring out flames and smoke,” according to a German report, before sliding below the surface at 7:08 pm on June 8.

The remaining British destroyer, the Acasta, then appeared to be heading away from the larger ships, laying smoke and picking up steam. Lt. Cmdr. Charles Glasfurd sent a message to his crew that they “were going to make a show.”

“Good luck to you all,” he said, before swinging Acasta 180 degrees around into its own smoke. As it closed on the Scharnhorst, Acasta fired its port torpedoes with one striking the starboard side of the battleship, killing two officers and 46 men. The British ship reentered the smoke before reemerging for another run at the enemy. Gneisenau fired and scored a solid hit to the aft section of the Acasta, which kept firing and hitting Scharnhorst, but causing little damage.

Two thirds of the Acasta was aflame as Gneisenau turned away to keep an eye on its sister ship. Acasta slipped beneath the waves shortly after 7:16 pm. Acasta’s lone survivor, Leading Seaman C. Carter, recalls seeing Surgeon Lieutenant H.J. Stammers attend the wounded and saw Glasfurd casually light cigarette and lean over the bridge to waive and mouth, “Good-bye and good luck,” to him aboard a raft.

Marschall called off the action and brought the damaged Scharnhorst into port at Trondheim, which is 560 miles south of Narvik. Fortunately for the Allies, Marschall’s decision to dock the Scharnhorst at Trondheim caused the two German vessels to miss a British troop convoy less than 160 miles away as it made its way back to Britain. When Scharnhorst put to sea again on June 20, Gneisenau was struck by a torpedo fired by a British submarine. Both made it to Germany for repairs, but neither vessel returned to duty until December 1940.

A great deal hinged on the self-sacrifice of the two British destroyers and Glasfurd’s determined torpedo run on Scharnhorst. Otherwise, Marschall very likely would have encountered the second convoy carrying approximately 20,000 troops, passengers, and crew. The loss of those troops and the additional ships would have truly shocked the British to the core just as the nation was recovering from the bloody and costly evacuation from Dunkirk.

As it was, the loss of one of four British carriers did have a significant impact on the Allies. Only 38 men survived the sinking of Glorious, and none of the battle-tested pilots who had seen action in Norway survived the sinking. The carrier, its crew, and the pilots would have played key roles in the coming Battle of Britain. As it was, more than 1,500 men were lost to the Allies in that naval action.

The Allies suffered approximately 12,000 casualties in the Norwegian campaign, with about 70 percent of those killed. As for the Germans, they experienced 5,296 killed, wounded, and missing.

The Kriegsmarine was prepared to lose half its fleet in the effort to take Norway and Denmark, and that expectation proved near the mark. The figures are staggering. Both of the German battleships took substantial damage, one heavy cruiser was sunk and another badly damaged, two light cruisers were sunk, and 10 destroyers and six submarines were lost.

Although written with the advantage of hindsight, Churchill noted in his memoirs that after Narvik the “German navy was no factor in the supreme issue of the invasion of Britain.”

Besides the carrier Glorious, the British lost two cruisers, seven destroyers, four submarines, and a number of armed trawlers in the campaign. Six British cruisers and eight destroyers were damaged but repairable. The French and Poles lost one destroyer and one submarine each.

The Germans claimed victory at Narvik, but that victory was largely a result of the Allies’ decision to reposition their troops in the face of the German victory in the Battle of France. Dietl was lauded in German reports for his “exemplary tenacity under great privations” against a “greatly superior enemy” that capitulated.

Despite the flowery rhetoric, it was clear that the Germans had won most of their objectives. The flow of the crucial Swedish iron ore was assured, and the Norwegian seaports and air bases would provide important launch points to choke off crucial supplies bound for Great Britain and the Soviet Union. Germany’s loss of so many ships and submarines would impede that effort to an extent, as would the Allied occupation of Iceland to form a defensive ring running from the Shetland Islands through Iceland to Greenland. The lack of large numbers of long-range Luftwaffe bombers also hampered the effort, both in Norway and later against Britain itself.

And, interestingly enough, the Germans had approximately 370,000 men and tons of war matériel deployed in Norway by the spring of 1945. This all was effectively unavailable to the Germans for the Battle of Berlin. Germany may have won the Battle for Narvik and Norway, but winning the war proved beyond its grasp.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments