By Patrick J. Chaisson

Four miles above the snow-covered city of Steyr, Captain Jack Horner peered down through his Norden bombsight in a desperate attempt to identify the target.

Horner was lead bombardier for a large force of Consolidated B-24 Liberator heavy bombers targeting the Daimler-Puch aircraft manufacturing plant some 90 miles west of Vienna. More than 100 other Americans were relying on him to find the factory and release his bombs—signaling to the rest to toggle their own payloads.

The task was made infinitely more difficult by especially aggressive swarms of Luftwaffe interceptors tormenting Horner’s bomber formation, even pressing in through deadly antiaircraft fire to disrupt its attack. Worse still, a stray cumulus cloud also momentarily obscured the factory.

Horner was configuring his bombsight for an “offset,” a technique used in bad weather conditions, when he spotted below him several errant Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress bombers. If he salvoed his bombs now, they would likely hit these friendly warplanes. He had no choice but to cancel the drop.

This unexpected development left Horner’s mission commander, Lt. Col. Kenneth A. Cool, with a particularly disagreeable dilemma. Should Cool order his Liberators to go around and try again, losing more aircraft to enemy flak and fighters. If the bombers attempted to strike their secondary target, precious time would be spent lining up on and attacking a low-priority objective.

Fortunately, Cool remembered from a pre-flight intelligence briefing that the sprawling Steyr Walzlagerwerke ball-bearing works sat on a direct line only one minute’s flight time from the Daimler-Puch factory. Vitally, sky was clear over this strategic production facility. Cool keyed the mic on his command radio: “Come to Course Three-Three-Zero. We’re bombing the ball-bearing plant.”

This mission, which took place on April 2, 1944, represented a major milestone in the Allies’ Combined Bomber Offensive. For 10 months, elements of the British Royal Air Force (RAF) and the U.S. Army Air Forces (USAAF) had been attacking key manufacturing facilities in an effort to permanently ground the Luftwaffe before the Allied armies invaded France.

Initially proposed in July 1943, the USAAF called it “Operation Pointblank.” The plan called for heavy bombers of the Eighth Air Force (stationed in the United Kingdom) and Fifteenth Air Force (flying from Italy) to strike high-priority industrial plants in central and southern Germany. As these factories made fighter aircraft and their component parts, destroying them was sure—in American eyes—to defeat the Luftwaffe.

Pointblank succeeded, albeit at a significant cost in men and matériel. In particular, “Big Week” (February 20–25, 1944) broke the Luftwaffe’s back in terms of airplane production. Forced to decentralize its manufacturing base, Nazi Germany could no longer build interceptors in sufficient quantities to challenge the Allies’ growing fleets of heavy bombers. Nor was the Reich able to adequately train replacement fighter pilots due to a chronic shortage of resources—notably fuel.

Eventually, though, the air units participating in Operation Pointblank shifted their focus to other missions. On April 1, 1944, control of the Eighth and Fifteenth Air Forces passed from Lt. Gen. Carl A. Spaatz’s United States Strategic Air Forces (USSTAF) to the Supreme Headquarters, Allied Expeditionary Force in Europe, under General Dwight D. Eisenhower. These bombers were needed to strike transportation nodes across northern France in order to isolate the Normandy region before D-Day—then scheduled for late May or early June.

Yet whenever conditions permitted, U.S. “heavies” went out against strategic targets even after Pointblank formally concluded. This was especially true for the Fifteenth Air Force (AF), commanded by Maj. Gen. Nathan F. Twining. Able to range far into southern Germany, Austria, and eastern Europe from their airfields in Italy, Twining’s airmen began bombing in earnest during the first months of 1944.

By April, the Fifteenth AF had on hand four full bomb wings. Of these, the 5th Bomb Wing (BW) was the only organization in Twining’s command equipped with B-17 Flying Fortresses. Flying B-24 Liberators were the 47th BW, 55th BW, and 304th BW. On paper, the Fifteenth’s bomber fleet totaled nearly 800 B-17s and B-24s. The number of operational aircraft was almost always lower due to combat losses and planes in maintenance.

These units flew out of the Foggia Complex, a sprawling network of airfields that encircled the city of Foggia in southeastern Italy. Also based there were upwards of 700 fighters assigned to the Fifteenth AF. The 325th Fighter Group (FG) operated the sturdy if short-legged Republic P-47 Thunderbolt, although some of its squadrons were transitioning to the new long-range North American P-51 Mustang. The 1st FG, 14th FG, and 82nd FG utilized the Lockheed P-38 Lightning, a versatile twin-engined escort capable of accompanying strategic bombers deep into Nazi-held territory.

About 20 miles southeast of Foggia stood the town of Cerignola, headquarters for the Fifteenth AF’s 304th BW. The 304th consisted of four Liberator-equipped bomb groups. First to arrive in Italy was the 455th BG, which shared a dual-runway airstrip at San Giovanni with the 454th BG. Stationed at Stornara Airfield was the 456th BG, while the 459th BG occupied another base at Giulia.

The 455th BG’s B-24s made their debut in the skies over San Giovanni on February 1, 1944. Approaching bombers held a tight formation as they circled the field, peeling off one by one to land. Aided by ground crewmen, lumbering Liberators taxied to their designated revetments and shut down. The 455th could now open an important new chapter in its combat chronicle.

The story of the 455th Bomb Group (Heavy) began nearly 10 months earlier when on July 8, 1943, it was activated at Clovis Army Air Base, New Mexico. The 455th had no airplanes of its own; instead, this headquarters organization provided command, planning, intelligence, logistics, and administrative functions for four subordinate flying units. These were designated the 740th, 741st, 742nd, and 743rd Bombardment Squadrons.

Each Bombardment Squadron (BS) was authorized 16 (later reduced to 12) Consolidated B-24 Liberators. Throughout the summer and autumn of 1943, U.S. airmen flew countless practice missions over the American Southwest as they perfected the deadly business of high-altitude strategic bombing. Members of the 455th BG honed their skills at installations in New Mexico, Florida, and Utah before moving to Langley Field, Virginia, in October 1943 to ready themselves for deployment.

Lieutenant Colonel Cool, a veteran airman fresh from a combat tour over Europe and North Africa with the Eighth AF’s 93rd BG, became the outfit’s first commanding officer. Many crew members remembered him as a strict taskmaster. Cool’s insistence on tight formation flying unnerved several newly-minted pilots who still had trouble taming the cantankerous Liberator.

The 743rd BS’s Lieutenant John Smidl called his bomber “The Beast.” Flying it, Smidl recalled, was “an excruciating experience.” For a novice aviator, he said, “All limbs were in motion at one time; left arm hauling and twisting, right hand sawing the throttle, feet jamming the rudder back and forth, mouth spouting curses…and, oh yes, the sweat pouring off my forehead and into my eyes.”

Smidl later reflected on his training, especially the emergency procedures that later saved his life over Europe. “The more we flew the more humble we became,” he observed. About his airplane, Smidl said, “The only pride I have is that after a year of struggle I finally learned to master the son-of-a-bitch and brought it to heel.”

Just before it departed the States, the 455th BG received 64 factory-fresh B-24H Liberators. With a wingspan of 110 feet, overall length of 67 feet, and a height of 18 feet, the H-model was powered by four Pratt & Whitney R-1830-65 engines, each rated at 1,200 horsepower. The bomber’s empty weight was just over 36,000 pounds, with a maximum loaded weight of 65,000 pounds.

Capable of reaching a top speed of 290 miles per hour and boasting a service ceiling of 28,000 feet, the Liberator had a maximum range of 2,100 miles. It could carry 5,000 pounds of bombs, although this payload was often reduced in favor of additional fuel needed to reach distant targets.

Each B-24 was manned by a crew of 10 — pilot, copilot, navigator, bombardier, and six gunners. For self-defense, the H-model carried 10 .50-caliber machine guns. Electrically-operated turrets in the nose, top, belly, and tail sported two guns each, while a single flexible weapon was mounted in both the right and left waist positions.

Throughout the war, proponents of the Boeing Flying Fortress quarreled with the Consolidated Liberator’s disciples over which plane was a better bomber. Each had its pros and cons. The B-17 was far more resistant to battle damage but flew slower than the B-24. The Liberator carried more bombs yet demanded constant attention in flight, unlike the older Fortress. The 455th’s flyers, none of whom had any choice in the matter, resolved to make do with whatever aircraft they were assigned to operate.

At Langley Field, the men of the 455th BG completed final preparations for overseas movement. The group then numbered approximately 2,260 officers and enlisted soldiers, including nearly 1,000 air crewmen. In December 1943, the outfit divided into two echelons—one designated to fly the organization’s B-24s into Italy with another detachment set to arrive by troop ship.

Around this time, Cool’s troops began calling themselves the “Vulgar Vultures.” While no one is certain how or where this moniker originated, an emblem was designed in cooperation with Walt Disney Studios. This patch, which depicted a perspiring buzzard clutching a demolition bomb, soon adorned the flight jacket of many a proud combat crewmember.

Despite a colossal effort by Army engineers, the field at San Giovanni was nowhere near ready for combat operations when the 455th BG arrived in January 1944. Neither of its two parallel 6,000-foot runways could yet accept bomber traffic, so the group’s air echelon waited for nearly three weeks at a staging base in Algeria until the flight strip was declared operational.

Those who arrived by sea discovered this so-called “airfield” was in reality just an olive grove. They would sleep in pup tents they brought with them, with slit trenches for latrines. The only building in sight was an ancient residence called “The Castle,” which Group HQ appropriated as an administrative space and senior officers’ quarters.

Men who expected to enjoy “sunny Italy” were sadly disappointed. Staff Sergeant Henry B. Everhart, a tail gunner with the 743rd BS, said he often endured “a wet penetrating cold with rains that produced a very slippery mud that was like ice” during his first few months in San Giovanni.

Even by Army standards, the food was bad. The Vulgar Vultures unit history described a typical breakfast as “Spam, Vienna sausages, stewed prunes and hash (heated in garbage cans), powdered eggs and bread.” Lt. Ernest F. “Bud” Turner of the 742nd BS added, “There was no mess hall. Food was prepared and dished out from a food line and you then found a place where you could eat your meal. Drums of hot water were provided for washing and rinsing your mess kits.”

Conditions eventually improved, which Everhart was quick to note. He remembered receiving larger six-man tents, which the troops then “set up between the olive trees.” The group also acquired some larger mess tents with picnic-style tables for troops to use at mealtimes.

Everhart also recalled building “a large common shower…for bathing. It [consisted of] a series of 10-gallon barrels sitting on beams overhead. The barrels were heated with wood under them. Pipes were connected to the barrels that had a chain you pulled to get a spray of hot water.”

With its B-24Hs in place at San Giovanni, the 455th BG stood ready to perform the duty for which it was trained and equipped. Bad weather, however, kept the Vulgar Vultures grounded until February 16, when 44 Liberators flew a mission that Cool scrubbed at the last minute due to heavy clouds. The group did complete a total of 17 small-scale raids during February and March, mainly in support of Allied ground troops at Anzio.

The coming of spring promised better weather, especially over the factories and railyards of southern Europe. The forecast for Sunday, April 2, prompted officers at Fifteenth AF to plan a full-scale raid on several strategic targets they had been unable to strike since February. The Austrian city of Steyr, home to several aviation-related industrial facilities, became their main objective. Train depots in Yugoslavia also merited attention.

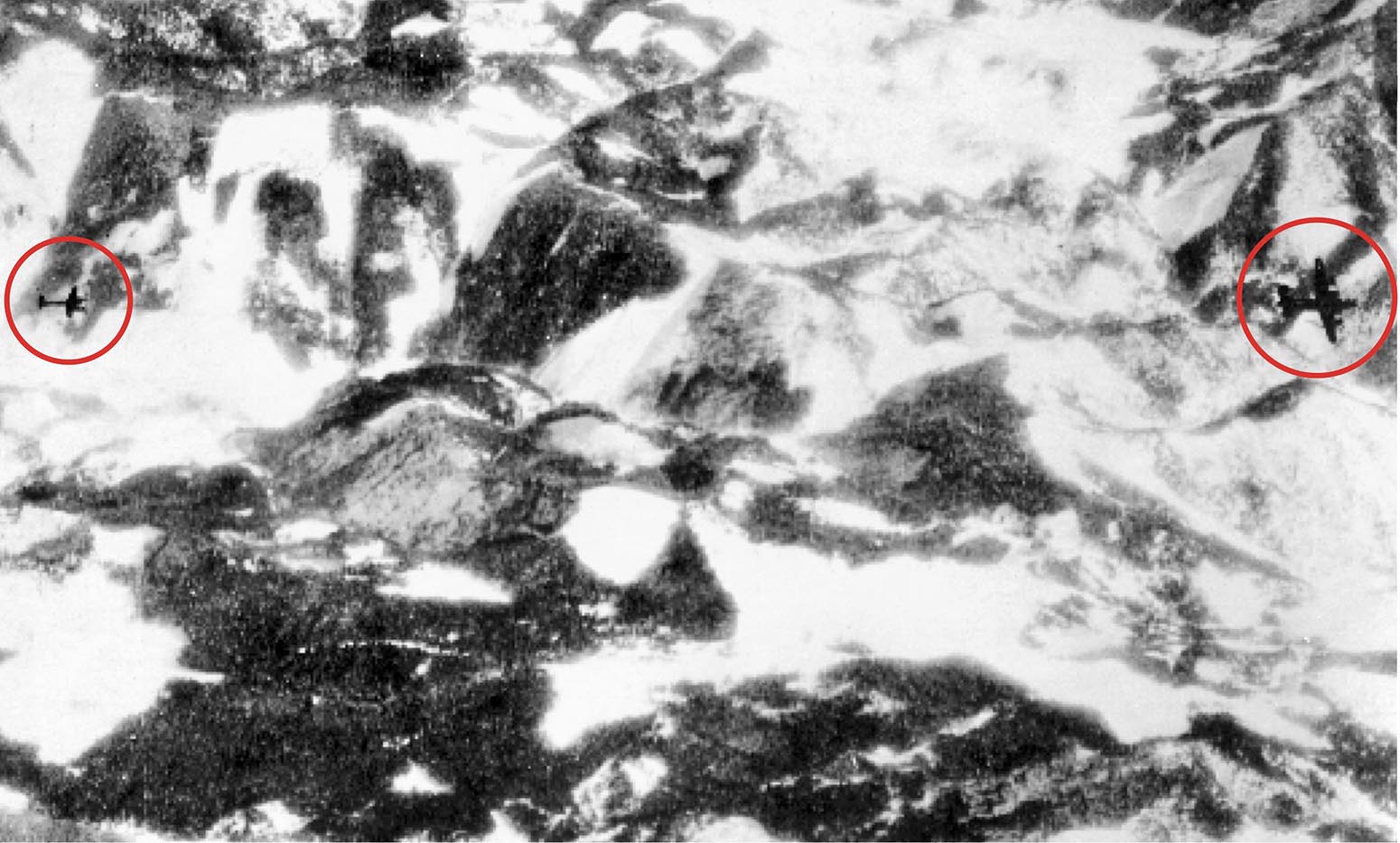

Twining declared it the Fifteenth’s largest mission to date. A total of 530 B-17 and B-24 bombers were to participate, 432 of them striking the Daimler-Puch aircraft factory and Walzlagerwerke ball-bearing plant in Steyr. The remaining 98 “heavies” would offer a diversion by attacking marshalling yards outside Bihac and Brod, Yugoslavia.

The plan required split-second timing. As the Flying Fortresses had a slower cruising speed, those planes would take off, assemble, and bomb first. The Liberator formations were to depart later, arriving over Steyr just after the B-17s departed.

More than 150 P-47 Thunderbolts and P-38 Lightnings would support the mission. These fighters employed a clever system of rendezvous points that ensured the bombers were covered throughout their 1,000-mile flight to Austria and back. Additional escorts remained available for when contact with the Luftwaffe was most likely—while crossing the Yugoslavian coast and during the final bomb run.

Coordinating instructions came down on April 1 through the Fifteenth AF and 304th BW to San Giovanni, where Cool’s operations staff crafted a field order. This document covered such details as takeoff time, weather en route, radio frequencies, and the target description. It also specified the number and type of bombs carried, as well as the quantity of .50-caliber ammunition and aviation fuel to be brought aloft.

The flight crews participating in Mission No. 18 (as this raid was designated) were awakened before 0400 hours on April 2. Dressing and eating quickly, they next received a briefing from the group staff. Senior officers reviewed the field order, taking care to provide updated information on sky conditions and likely enemy threats.

Cool presided over the briefing. In his closing comments, he said the 455th would act as lead group for all Liberator units attacking Steyr. “This one’s for me,” he said, announcing he would pilot the first ship going out that day. This pleased the airmen, who knew that whenever “the Old Man” ran things personally their mission normally succeeded.

Crew members next walked to the equipment tent, where they donned heavy sheepskin-lined leather overgarments and parachute harnesses. They also drew escape kits from the intelligence officer (S2). Bud Turner described this survival gear as “a small plastic box containing a map of the area where they were going, a $5 gold coin, a fishing hook and line, a small compass, and a small hacksaw.” He added, “The kit would be returned to the S2 people at the end of the mission.”

Some flyers put on electrically-heated flight suits and boots, but these bright blue outfits short-circuited frequently and often burned their wearers. Others took to hanging a pair of G.I. issue shoes around their necks in case they were shot down. Heavy flak jackets and steel helmets were available, but not everyone could fit inside the close confines of a B-24 while clad in this bulky body armor.

Station time—when all crews needed to be on board and ready for action—came at 0648 hours, just after sunrise. Shortly thereafter, Cool started the engines on his aircraft, nicknamed “BESTWEDO” after one of his favorite expressions. Takeoff commenced at 0755 hours, with 35 Liberators of the 455th BG getting airborne. One ship returned early with a fuel leak, while the rest began arranging themselves into what was termed a “combat box.”

This formation, which effectively massed defensive firepower against enemy interceptors, normally contained 40 planes divided into two units of 20 B-24s each. Each unit consisted of three squadron boxes. The mission commander led the center box of six bombers, while on either side were seven ships each in the left and right combat boxes. The second unit flew closely behind the lead element while “stacking” itself downward slightly.

Assembling the group took time, but by 0845 hours the Vulgar Vultures were on their way. Behind them trailed 200 more Liberators. In Austria, meanwhile, a well-trained reception committee prepared to welcome the 455th with deadly bursts of flak and aircraft fire.

The Germans’ first indication of a raid that morning came from radio intelligence stations listening for Allied transmissions. American flight crews exhibited notoriously poor radio discipline, which enabled Luftwaffe monitoring posts to learn much about their enemy’s composition, route, time of attack, and even the objective.

Radar operators established the raiders’ current location, heading, and airspeed as they gained altitude over the Adriatic Sea. Fifteenth Air Force formations rarely feinted; once the bombers’ base course was determined, Luftwaffe analysts could easily predict their destination. The presence of USAAF weather planes (usually unarmed reconnaissance versions of the P-38) overhead typically validated this electronic intelligence data.

The Reich’s air defenses were centrally coordinated by a headquarters element known as Jagdkorps I, based in Braunschweig. A number of subordinate fighter division command posts managed the Luftwaffe’s local response to Allied air raids—for instance, Jagdivision 7 (headquartered near Munich) was responsible for the defense of south-central Germany and Austria. On the morning of April 2, controllers at Jagdivision 7 began alerting single-engined and twin-engined interceptors of the Reichsluftverteidigung (RLV, or Reich Air Defense Force) to prepare for action against a large Austria-bound USAAF raid heading north from Italy.

Several combat-tested interceptor outfits made up the RLV. Flying from Wiesbaden, II Gruppe Jagdgeschwader 27 (Second Group, 27th Fighter Wing—abbreviated II./JG27) had recently taken up air defense duties after departing North Africa. Its unit designation, “Afrika,” reflected JG27’s long service there. Another experienced fighter command, II./JG77 (nicknamed “Ace of Hearts”), flew off a grass airstrip at Canino in west-central Italy.

Both groups operated the Messerschmitt Me-109G-6. This single-engined interceptor was armed with two 13mm machine guns mounted above the engine, one 30mm cannon firing through the propeller hub, and occasionally two more 20mm or 30mm weapons carried in under-wing gondolas. Known as “Gustav” by its pilots, the G-6 represented a good mix of firepower and performance.

Operating from Wilz, Austria, the “Wasps” of II Gruppe Zerstörergeschwader 1 (Destroyer Wing One—abbreviated II./ZG1) operated a day-fighter version of the two-engined Messerschmitt Me-110G-2. Slow but heavily armed, the Me-110 could approach enemy bombers from the rear and lob 210mm rockets into USAAF formations before closing in with its two 30mm autocannons. Three or four hits from these powerful guns were normally sufficient to destroy a “dicke Auto” (slang term for an Allied heavy bomber—literally, “fat car”).

All told, the RLV mustered 312 single- and 62 twin-engined interceptors against the Fifteenth AF on April 2, 1944. They heavily outnumbered the U.S. escort fleet, and many Luftwaffe fighters sortied twice—once as the bombers approached and again during their flight home.

Another unpleasant surprise awaited the Vulgar Vultures at Steyr. More than 100 antiaircraft guns, 88mm and 128mm, all pointing skyward, ringed the city. These large-caliber weapons were crewed by the men and women of 24. Flak-Division, a large Luftwaffe command responsible for the defense of upper Austria.

Meanwhile, the American bombers were making their way north under near-cloudless conditions. Two more 455th BG B-24s aborted the mission with mechanical issues, leaving 32 planes in the lead combat box as it penetrated Yugoslavia at 1020 hours. Ten minutes later, over Novo Mesto, the first German interceptors appeared.

Major Horace Lanford, flying as Cool’s copilot, recalled what happened when the 455th BG came under attack at 1045 hours. “Inbound to the target, we were alerted by the top turret gunner that seven Me-109s were overtaking the Group on our right flank. I observed seven Me-109s fly up to the head of the column, opposite our aircraft, in single file. [They then] turned into the formation flying seven abreast on their firing run.”

According to Lanford, “I immediately called the fighter escort: ‘Red Dog 1, this is Large Cup 23. We are under attack by seven Me-109s and request assistance.’ Red Dog 1 responded: ‘Wa-l-l (Southern drawl) we’re kinda tied up ourselves right now but we’ll send someone up as soon as we can…’ A single P-38 appeared shortly and the Me-109s withdrew.”

Air attacks on the Vultures grew more intense as they neared Steyr. “The heaviest concentration of [enemy] fighters was encountered 15 miles west of Graz,” wrote Group Intelligence Officer Major Alvin E. Coons, “and continued the attack until the target area.” Coons identified these “bandits” as Messerschmitt Me-109s and Me-110s, as well as several Focke-Wulf Fw-190s.

“The Me-109s and Fw-190s attacked low and level,” Coons reported, while “twin-engined aircraft made attacks from the rear, firing rockets into the formation.” He evaluated the men flying these interceptors as “very aggressive” and “experienced pilots.”

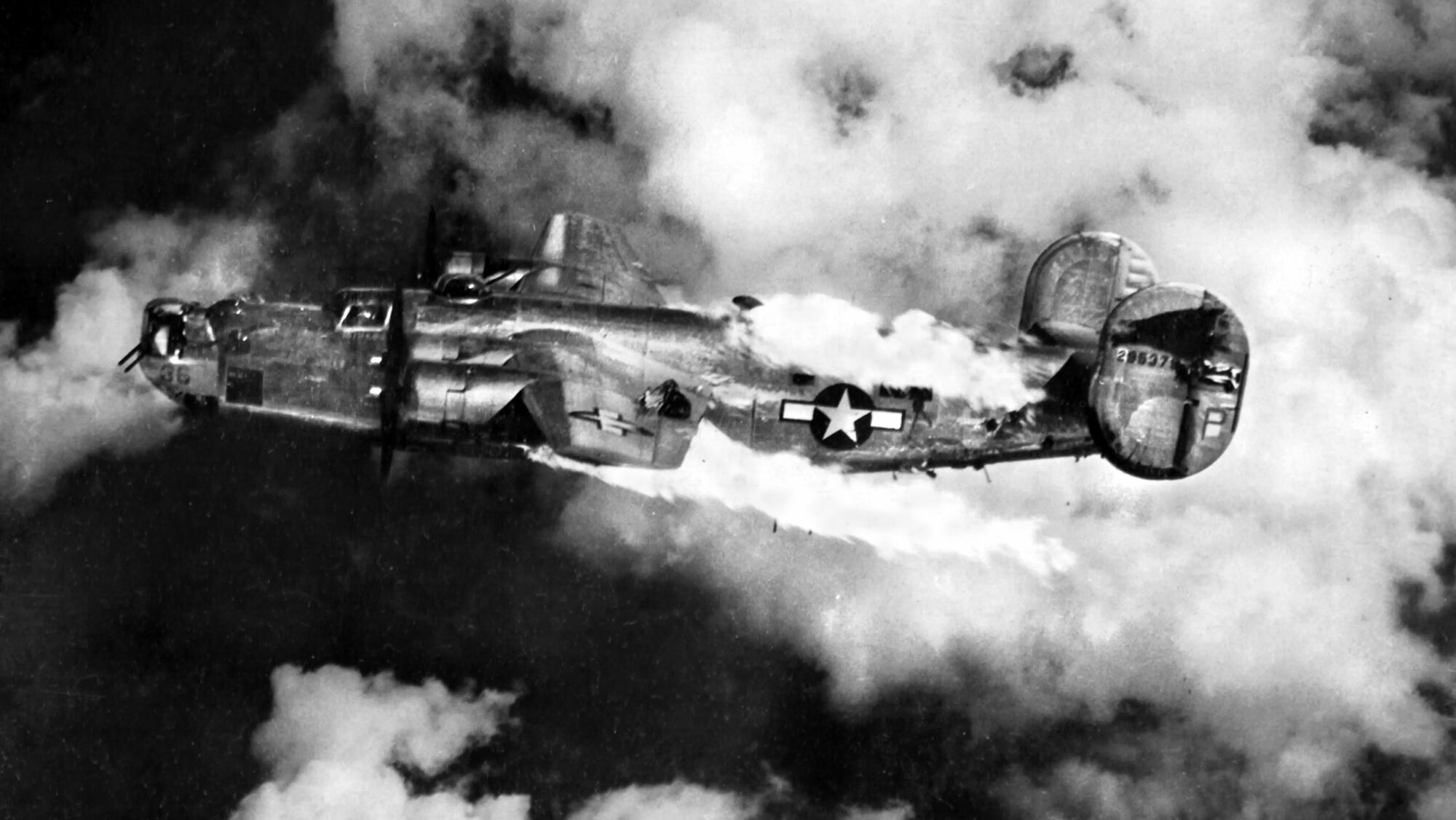

Horrified squadron mates looked on helplessly as bombers began to die. The first Liberator destroyed was “DOUBLE TROUBLE,” a 742nd BS ship crewed this morning by 2nd Lieutenant John H. Powers Jr.’s 740th BS crew. While under attack by enemy fighters, the B-24 broke formation at 1100 hours with its left wing and No. 3 engine engulfed by fire. Five crewmembers bailed out to become prisoners of war. The other five airmen were killed.

At 1115 hours, 1st Lieutenant Willis J. Pardoe’s “SHOO SHOO BABY” turned for home with its No. 4 engine shot to pieces. Unprotected, the 742nd BS Liberator endured incessant air attacks for over 30 minutes. After his gunners expended their .50-caliber ammunition, Pardoe ordered the crew to jump. Five men were taken prisoner, but the rest evaded capture with the help of Yugoslavian partisans. One month later, these lucky flyers returned to San Giovanni.

Another B-24, “GREMLIN’S GRIPE” (commanded by 1st Lieutenant Clyde P. Brunson of the 743rd BS), dropped behind the formation at 1130 hours. Flight Officer Richard J. Haney, flying on Brunson’s wing, witnessed this bomber making “a slow descending turn to the right with [its] left wing, engine and left rudder on fire. Two men were seen bailing out and one chute opened. I then saw the ship blow up.”

It was learned later that eight crew members managed to escape, but all were made prisoner. German records credit Luftwaffe ace Captain Hans Remmer of JG27 with downing Brunson’s Liberator, his 27th and final kill. Remmer perished later that day in an encounter with P-38 Lightning escort fighters.

As the Vulgar Vultures approached Steyr, the sky around them erupted in a man-made cloud of lethal flak. A tail gunner with the 740th BS, Staff Sergeant Don Kaplanek, spoke for thousands of aircrewmen flying on April 2 when he described this barrage as so thick “you could just get out and walk on it.” Although no 455th BG B-24s were lost to antiaircraft fire, three ships were damaged severely while four more required minor repairs.

In the nose of Cool’s plane, Group Bombardier Horner forced himself to ignore the bursting flak, attacking interceptors, and falling Liberators. Horner had a difficult task. He first needed to identify his target, then place it in the crosshairs of his Norden bombsight so that device could calculate a release point for the 10 500-pound bombs carried on board.

When clouds and a flight of misoriented B-17s made Horner call, “No Drop!” his mission commander coolly diverted the formation to the alternate objective. Lining up on the nearby Walzlagerwerke ball-bearing factory, Horner salvoed at 1140 hours the first of nearly 2,300 demolition bombs to fall on this key industrial facility.

“Many direct hits were scored on the [factory’s] machine shops,” a Fifteenth AF report boasted, “and a large explosion occurred, covering the plant with dense smoke.” In his post-mission analysis, Group Intelligence Officer Major Coons declared, “The assembly, testing, packing and ball and roller bearing [building] was very heavily damaged. Of the total area of 116,000 square feet, only 43,000 square feet remained and that suffered internal damage.”

The Luftwaffe, however, was not done with Cool’s formation. At 1145 hours, gunfire from enemy interceptors caused 1st Lieutenant Roy R. Cheeseman’s 743rd BS ship “TALLAHASSEE LASSEE” to fall out of position. Witnesses observed flame enveloping the plane’s bomb bay and waist position as it passed from view. Four flyers made it out of the stricken Liberator; they were quickly captured while the remains of those six individuals unable to escape were found later by German patrols.

Bomber crews now making their exit from the hellscape over Steyr were relieved to spot several approaching P-38s that swatted away the Luftwaffe’s most persistent interceptors. Most airmen described their flight home as a relatively routine one. Yet for 1st Lieutenant William A. Arnold and his 743rd BS ship “TURBO-CULOSIS,” quite the opposite was true.

While about 20 minutes from its objective, Arnold’s B-24 was attacked by marauding Me-109s. “A fighter came within about 50 yards of us,” Arnold recalled, “and Pete (Technical Sergeant Roland R. Keith) in the top turret with his twin .50s sent him down on fire.”

Arnold’s account continued: “Then we were hit!! TURBO-CULOSIS shuddered and lost airspeed. No. 4 engine was on fire and No. 2 engine was damaged. We were unable to keep up with the Group and it was rapidly pulling away from us. The life expectancy of our aircraft in this situation could probably be measured in seconds.”

Bill Arnold’s co-pilot, 2nd Lieutenant Richard “Dusty” Dunscomb, extinguished the engine fire but then a new crisis revealed itself. The plane, now gradually losing altitude, needed to lose weight if it was to make it over the Alps. First, the bomb load was jettisoned. Then out went waist guns and flak suits, even one flyer’s parachute. Six and a half hours after it took off, TURBO-CULOSIS completed a “more or less normal landing” at San Giovanni. Some of her crew, Arnold wryly observed, “were seen to kiss the ground” afterward.

At a cost of four Liberators and 40 crewmen, the Vulgar Vultures delivered a powerful blow to the Reich’s industrial capacity. Additionally, the outfit’s aerial gunners received credit for 27 enemy interceptors destroyed and another 17 planes listed as probably killed.

Victory claims on both sides were often greatly inflated. The RLV admitted to losing seven planes (all Me-109s) on April 2, a figure far lower than what the USAAF said it downed. Likewise, German interceptors claimed credit for 16 B-17s, 34 B-24s, four P-38s, and one P-47 that day. The Fifteenth AF’s actual losses were eight Fortresses and 20 Liberators, with no escort fighters reported as missing.

There was little rest for the 455th following its ordeal over Austria. An order presently came down detailing 28 B-24s to bomb railyards in Budapest, Hungary, with takeoff set for early the next morning. Hardworking mechanics, armorers, and fuel personnel—the unsung heroes of the Fifteenth AF—labored all night to prepare their planes for the group’s 19th mission.

For their lead role in the destruction of a strategic manufacturing facility at Steyr on April 2, 1944, the Vulgar Vultures received the first of two Distinguished Unit Citations they would earn during the war. During their 15 months of service in Italy, these airmen flew 252 combat sorties and delivered 14,702 tons of bombs. Balanced against this record of success were 118 aircraft lost to enemy fire or accident, as well as 147 crewmembers killed in action, 268 listed as missing, and 179 made prisoner.

The 455th BG was but one of many American bomber groups to serve in combat from 1941-1945. As did every USAAF flying unit, the Vulgar Vultures regularly performed extraordinary feats of valor and daring in a harsh, unforgiving environment. Their courage, skill, and sacrifice helped win World War II.

Patrick J. Chaisson is a retired military officer and historian based in Scotia, New York.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments