By David Alan Johnson

By early 1944, the Luftwaffe was only a shadow of what it had been at the beginning of the war. Adolf Hitler and Reichsmarshal Hermann Göring were determined to retaliate against British cities, especially London, for Allied air attacks against German cities. A few years earlier, they would have ordered a series of massive air raids against London in reprisal. However, combat losses and the switch to fighter production for the defense of the Reich had drained the strength of the Luftwaffe’s once-powerful bomber fleets. Massive air strikes were no longer an option.

German engineers had developed new and unconventional methods of striking back at the enemy. The Fieseler FZG-76 flying bomb, which would be known as the V-1, was one of the weapons designed for striking at targets in Britain without straining the Luftwaffe’s already depleted bomber reserves. The V-1 was popularly known as the “buzz bomb” to the Allies because of the distinctive noise created by its pulse-jet engine. Theoretically, the V-1 operated with a simple guidance system and was supplied with enough fuel to reach a major target in England or Allied territory on the Continent. Once above the target, the V-1 would have expended all its fuel and begun a random descent to the ground, its warhead detonating on impact.

One of the flying bomb’s many problems, however, was that it was so inaccurate. The bombs sometimes missed a target as large as Greater London, which covers hundreds of square miles, by either flying beyond the entire city or, usually, crashing far short of it. Certainly, the sheer randomness of the attacks contributed to terrorizing the enemy populace, but greater accuracy would have been beneficial from a military standpoint. One way to solve this problem would be to develop a manned V-1: to put a pilot in the unmanned flying bomb.

Luftwaffe headquarters ordered that all special assignments, including the testing of all experimental aircraft, were to be carried out by Kampfgruppe 200, a secret unit that operated from several airfields on the occupied Continent. One staffel (squadron) of KG 200 was formed to operate the manned version of the flying bomb. This unit adopted the name “Leonidas staffel.” Leonidas was the legendary king of Sparta who had fought the Persians at Thermopylae in 480 bc. His stand at Thermopylae was determined to the point of being suicidal. Leonidas and every one of his 300 Spartans were killed in the fighting. The name of the staffel indicated the intention of the unit in its unconventional attacks.

The first attempt at a manned flying bomb had ended in failure when a bomb-carrying Focke Wulf FW-190 fighter aircraft was employed in tests. This idea was scrapped because the fighter was too vulnerable to enemy fighters. The additional weight of the bomb had made the Focke Wulf slower and much less maneuverable. Hauptsturmführer (SS Captain) Otto Skorzeny, the commando leader who became famous following his daring rescue of Benito Mussolini from captivity in the Italian Alps, is said to have suggested modifying a FZG-76 flying bomb to carry a pilot. The FZG-76 could outrun any piston-engine fighter and carried a warhead of almost one ton. With a pilot to guide it, this aircraft would be able to find any target, no matter how small, and would deliver enough explosives to destroy it.

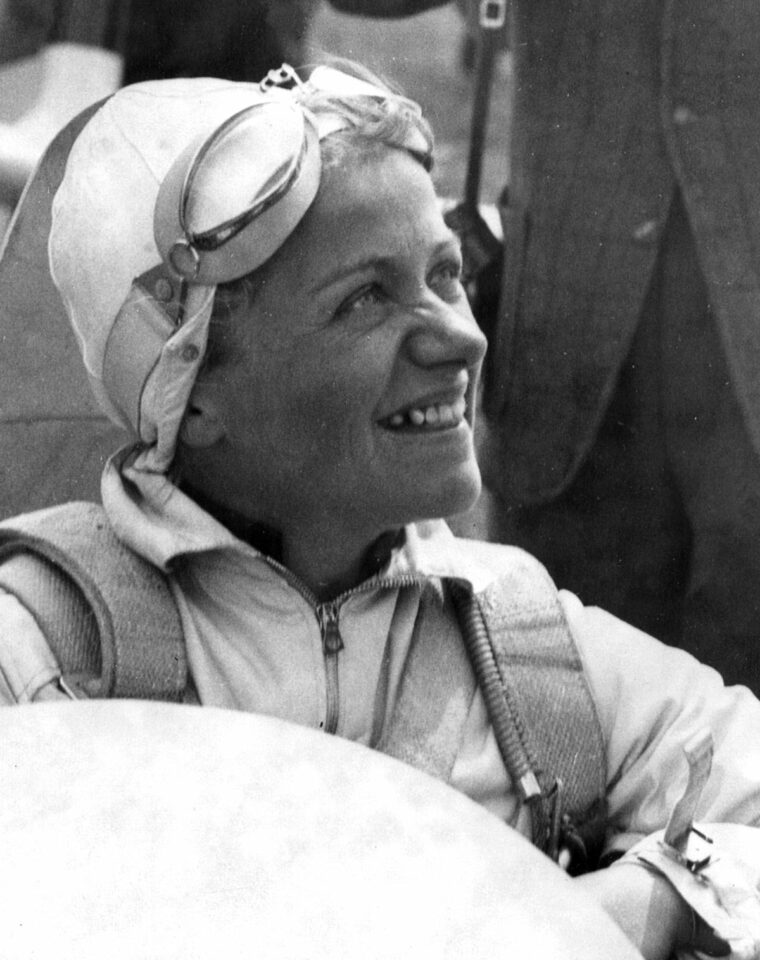

A piloted version of the FZG-76 already existed, although it had been designed strictly for testing. Early models of the flying bomb had many problems with stabilization. The craft kept crashing shortly after being launched. The well-known pilot Hanna Reitsch, an aviatrix who had achieved fame before World War II and become a favorite of Hitler, was assigned to make a test flight of a manned FZG-76 to evaluate the machine’s stability. Reitsch, the first woman to hold the honorary rank of captain, had also been awarded the Iron Cross First Class. Because of her record as a pilot, which included testing an experimental helicopter in the mid-1930s, she was given the job of finding out exactly what was wrong with the FZG-76 and what should be done to fix the problem.

The modified flying bomb, with Hanna Reitsch in the cockpit, was air-launched from a Heinkel He-111 twin-engine bomber.

Catapulting the machine from a ramp, which was the usual procedure, was considered too dangerous.

Reitsch lived up to her reputation as one of Germany’s leading pilots by bringing the FZG-76 to a safe and successful landing after a harrowing flight. Her suggested changes to make the machine more airworthy were implemented by the designers at Fieseler and were instrumental in the success of the V-1 campaign against London in the summer of 1944. The more popular designation “V-1” was short for Vergeltungwaffen 1, or Vengeance Weapon No. 1, which sounded much more dramatic than FZG-76.

Reitsch’s test flight had prompted Skorzeny to suggest turning the flying bomb into a manned aircraft, which would be sent against enemy targets. The project was first called “Selbstopfer,” which translates as “self-sacrifice.” It was soon changed to the much less ominous sounding “Reichenberg.” Fieseler designers gave the cockpit version of the machine the official name of Fi 103R.

The first trials of the Reichenberg flying bomb, which began in September 1944, were not very promising. Two test aircraft were manufactured, and both machines were lost during their first flight. Because an expert was needed to carry out trial flights, the tests were taken over by Reitsch, who was no stranger to unconventional aircraft. Besides her flight in the first manned FZG-76, she had also tested the rocket-powered Messerschmitt Me-163 Komet, a fighter interceptor that was to be deployed against formations of Allied heavy bombers above the Reich. She had been severely injured during these test flights, which left her hospitalized for five months.

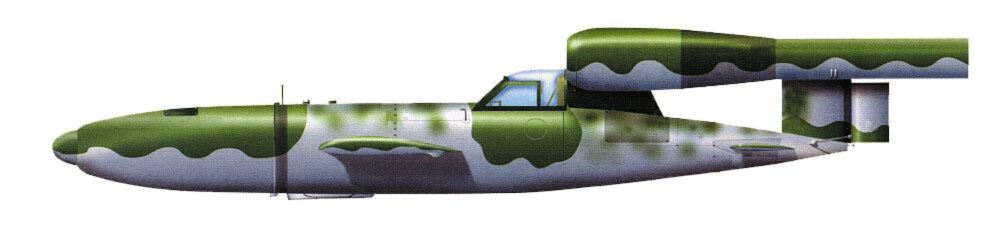

Under the Reichenberg program, four piloted FZG-76 models were built. Reichenberg I and II were unpowered training models, designed for gliding trials. Reichenberg II had an additional cockpit added to accommodate an instructor. Reichenberg III was a powered training model, with an Argus pulse-jet engine. Reichenberg IV was the operational model.

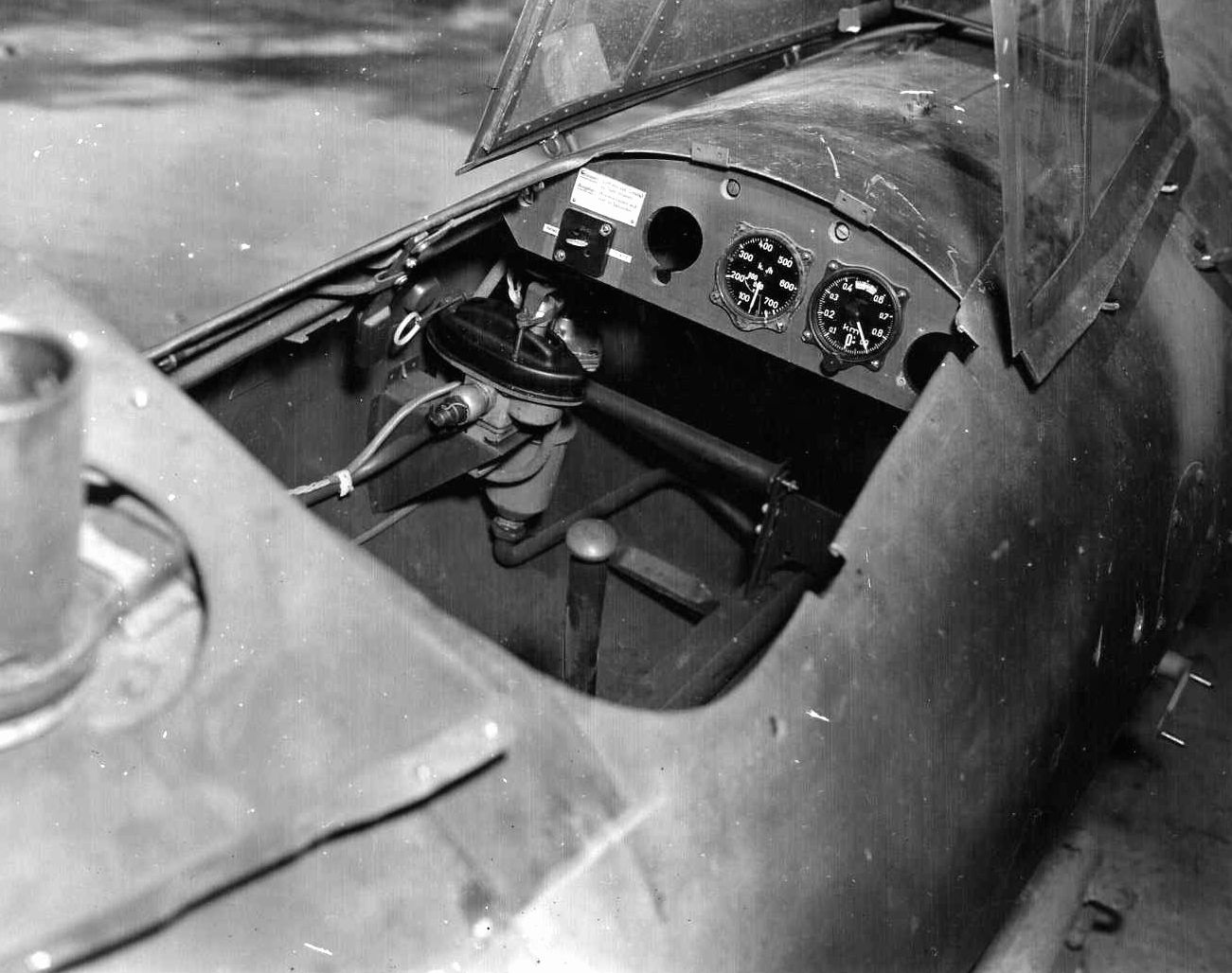

The cockpit of the Reichenberg IV was situated just in front of the engine. The pilot sat in a molded bucket seat and used a conventional stick and rudder bar to control the aircraft. Instruments consisted of an altimeter, airspeed indicator, clock, turn-and-bank indicator, and an arming switch for the warhead. The pilot was also provided with guidelines for calculating diving angles, which would prevent him from overshooting or falling short of his target.

The Reichenberg was not meant to be ramp-fired. Reitsch agreed that launching the manned flying bomb from a ramp would be too dangerous for the pilot. He would have no chance to escape if the guidance system failed, as often happened with the conventional FZG-76, resulting in a crash just after takeoff. A Heinkel He-111 would take the Reichenberg to within launching distance of its target, just as in the initial test flight by Reitsch. An intercom system allowed the pilot to talk to the Heinkel’s crew during flight. Because there was no way to enter the Reichenberg’s cockpit after takeoff, it was slung under the Heinkel’s port wing, not under the bomb bay. The pilot had to board the missile before taking off.

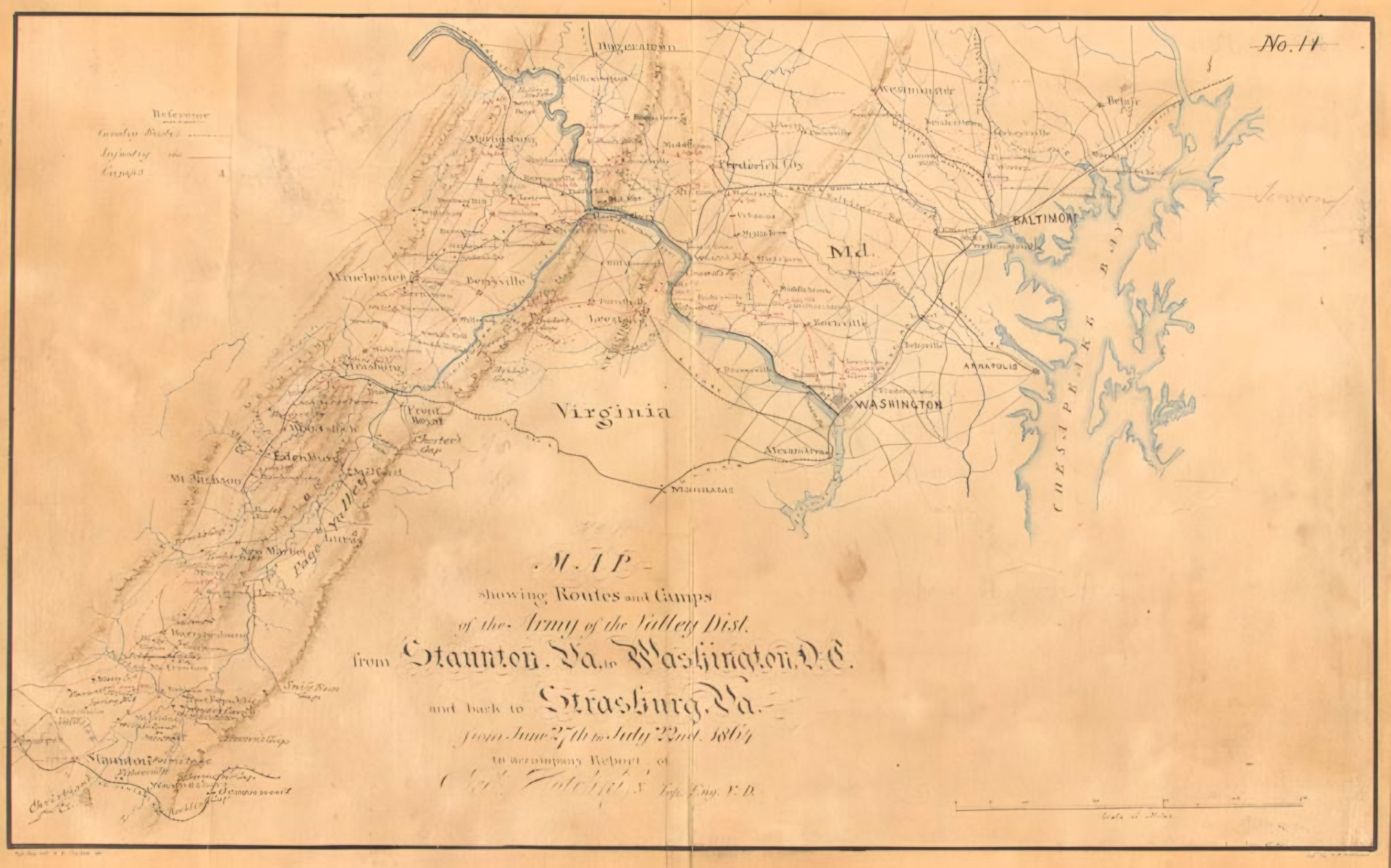

When the Heinkel reached the vicinity of the target, the Reichenberg’s pilot started the pulse-jet engine. Targets earmarked for the Reichenberg included bridges, shipping, small but vital installations (such as Battersea Power Station in London), and military bases that might be too heavily defended for a conventional aircraft to attack. The Heinkel would climb to about 20,000 feet and, after getting the approval of the Reichenberg’s pilot, would drop the missile.

After being cast off, the Reichenberg pilot was on his own. His first task was to get his aircraft to level off—no mean feat, considering the FZG-76’s history of malfunctioning. After gaining control of the missile, he would point it in the direction of his target and, finally, would arm the 1,900-pound warhead. The Reichenberg would be traveling at about 450 miles per hour at this point.

By October 1944, a Total of 175 FZG-76 Flying Bombs had Been Modified with Cockpits and Manual Controls.

After arriving over the target, the pilot would aim the missile and push over into his final dive. The pilot did have the option of bailing out. The Reichenberg program was not specifically suicide-oriented, and there was a procedure for the pilot to jettison the cockpit hood and jump clear. However, chances of getting clear of the diving aircraft were slim, at best. The procedure for detaching the cockpit hood was fairly complicated, especially at 450 miles per hour, and the intake of the pulse-jet engine would probably have pulled the pilot right in. It would have been highly unlikely for the pilot to be able to jettison the hood, much less jump free of the missile.

Training the instructors for the Reichenberg project had already begun, and a program for recruiting pilots had also been approved. To crash into a target with nearly a ton of high explosives required a fanatical determination on the part of the pilot, as well as a personality that verged on the manic. However, Nazi Germany produced a good many individuals who possessed these attributes in abundance. Sixty pilots from KG 200 along with 30 of Otto Skorzeny’s commandos volunteered for the Reichenberg project. Other recruits could have been found, as well, from the ranks of other Luftwaffe units and the Waffen SS.

By October 1944, a total of 175 FZG-76 flying bombs had been modified with cockpits and manual controls. Reitsch carried out a test of an unpowered version and brought the Reichenberg I to a successful touchdown on its wooden landing skid. However, during that month, command of KG 200 was taken over by Oberstleutnant (lieutenant colonel) Werner Baumbach, who had no faith whatsoever in the Reichenberg project and let his views be known. He thought that the program was a total waste of both manpower and matériel, which were becoming increasingly scarce in Germany. Shortly after he took command, the project was scrapped.

Had it been allowed to continue, the Reichenberg Project would almost certainly have had at least some degree of success. Japan had a similar project, which employed a similar aircraft—the rocket-powered Ohka (cherry blossom) kamikaze. The Ohka was a single-seat, wooden aircraft. It was carried to the vicinity of its target by a twin-engine Mitsubishi G4M Betty medium bomber, and it carried an 1,800-kilogram warhead. The Ohka program was employed successfully against U.S. shipping in late 1944 and in 1945. Among the many ships that were sunk by these piloted missiles was the destroyer USS Mannert L. Abele on April 12, 1945, off the coast of Okinawa.

The Reichenberg manned V-1 flying bomb could have been Germany’s ultimate cruise missile—literally a missile with a man in it. Although it was the Luftwaffe’s most unorthodox weapon, it was never used operationally. The degree of damage inflicted if the “German kamikaze” had been used against Allied targets is still open to speculation.

David Alan Johnson is the author of the book The City Ablaze, which is an hour-by-hour eyewitness account of the December 29, 1940, fire blitz on London. He resides in Union, New Jersey.

very good story