The 1942-43 struggle for Guadalcanal Island has, to my mind, an odd place in American memory. Americans are familiar with it, know it as a victory, but do not accord it the same honor as the Battle of Midway, or of Tarawa or Iwo Jima. In several respects it should be held in higher honor than any of these.

Midway is often celebrated as the turning point in the Pacific War. It is not hard to see why. The Japanese presented an awesome display of power, as well as boundless confidence in a navy that had never known defeat. A weakened U.S. force had little going for it except superior intelligence work. The battle turned in five minutes on astonishing luck for the Americans.

Tarawa and Iwo Jima, of course, are Marine icons. All-Marine affairs, they pitted U.S. martial prowess against formidable defenses.

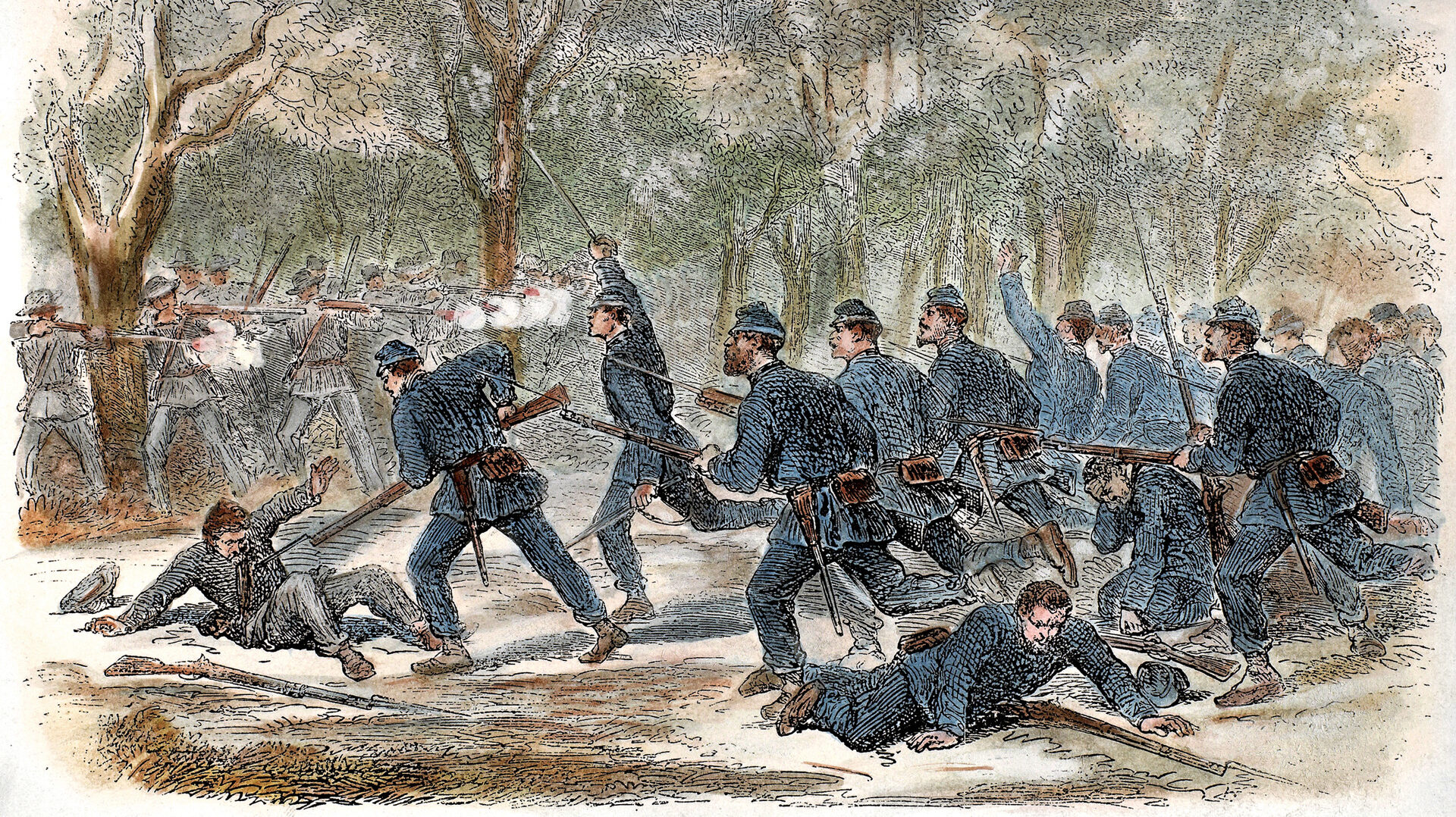

But the memory of Guadalcanal has been forced into a different channel. The battle preceded the introduction of the famed Marine camouflage helmet, so that photographs of Marines make them look like Army soldiers, muddying the waters of collective memory. Compounding that confusion is the fact that Army soldiers fought there in abundance. In addition, Guadalcanal was far from being only a land-based show; flyers and the Navy were also heavily engaged and took horrendous losses.

Nor was the contest for Guadalcanal brief, allowing legend to neatly wrap it. The struggle lasted from August to February. Nor was it simple. Complex sea battles marked the struggle, some so shockingly disastrous for the U.S. Navy it would seem that Americans were trying to forget them. In addition, some hours of the day the Japanese held air and sea superiority; sometimes the U.S. did.

Muddled as the memory of Guadalcanal is, the battle was the real turning point in the war between Japan and the U.S. In order to “win” the war, Japan had to achieve some astonishing victory that would cripple the American resolve to wage war and to gain a bargaining chip with which to achieve a negotiated peace in its favor. This could have been occupation of Hawaii or India or some portion of North America or Australia or the like. Thus it had to “not lose” Guadalcanal. Doing so would allow the Americans to believe they could win if only they kept fighting and would blunt any move to a major Japanese seizure of even more territory than they had taken by July 1942.

Thus both sides threw in all their armed services ; the Americans to hold on to Henderson Field on the island, the Japanese to expunge the Americans from the island all together. Day after day, week after week, month after month the contest went on.

Herman Wouk in his novel War and Remembrance likened Guadalcanal to Stalingrad. Both struggles began at about the same time and both ended in February 1943. Both set the stage for the decline in fortunes for the Axis aggressors. Losing Guadalcanal, Japanese Admiral Yamamoto understood, meant losing the war against the Americans. Calling for a withdrawal from the island, Yamamoto could see that the U.S. had demonstrated the will and the capacity to win and that, barring a miracle, the Japanese could only delay the inevitable.

The U.S. Marines did not look like Marines; the ships looked like leftovers from the 1920s and 1930s (they were), not the fresh-looking ships of 1944-45; the aircraft were obsolete; some of the naval encounters were astonishing embarrassments. But for all this, the battle of Guadalcanal should be recalled as the time when Americans drew their line in the sand and said, “This and no farther. We stand here, and you will see.” They meant it, God bless them every one.

Brooke C. Stoddard

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments