By Scott McGaugh

During the decade of the U.S. Army’s experiment with gliders in war, nearly as many glider pilots died in training as they did in combat. The Waco CG-4A gliders, fabric-wrapped metal tubing with a wooden floor, were nicknamed by others as “Death Crates,” “Tow Targets,” “Plywood Hearse,” and “Flying Coffins.” Given the conditions for its deployment, the aircraft performed surprisingly well—a one-way mission behind enemy lines with no motor, no parachutes, and no second chances. American glider pilots had flown perilous missions at the tip of the Allied spear all across Europe and many felt slighted by a lack of recognition or awards after the war. They had left as innocent young men who had seen little more than a fistfight. They returned hardened, many haunted, some bitter, and a few alcoholic. Such is the legacy of war. Crippling scars. Nightmares. Sights and sounds that remain as fresh as yesterday.

Joseph had been bound for medical school. Sam was working in a logging camp; Stephen on neighbors’ farms. Lawrence hated his Navy posting in Puerto Rico. On the eve of World War II, they were among thousands of young men who dreamed of becoming a fighter pilot. Instead, they were destined to climb aboard a motorless aircraft not yet invented.

They would become combat glider pilots, led by a man who had been the second choice of both his father and the U.S. Army when he applied for admission to West Point. Henry “Hap” Arnold, from Gladwyne, Pennsylvania, a wealthy Philadelphia suburb, was a likable fellow, prone to pranks, and later admitted he was a minimal-effort cadet. He graduated 66th in a class of 111.

Arnold’s prospects for an Army career were dim at best, and at one point he suffered from a profound fear of flying. But by the mid-1930s, he had developed a reputation for aircraft research and development—and surprisingly cheerful, cooperative, and inspirational leadership skills. In 1938, Arnold, now a general, took command of a moribund Army Air Corps at the start of the pre-war’s aviation arms race.

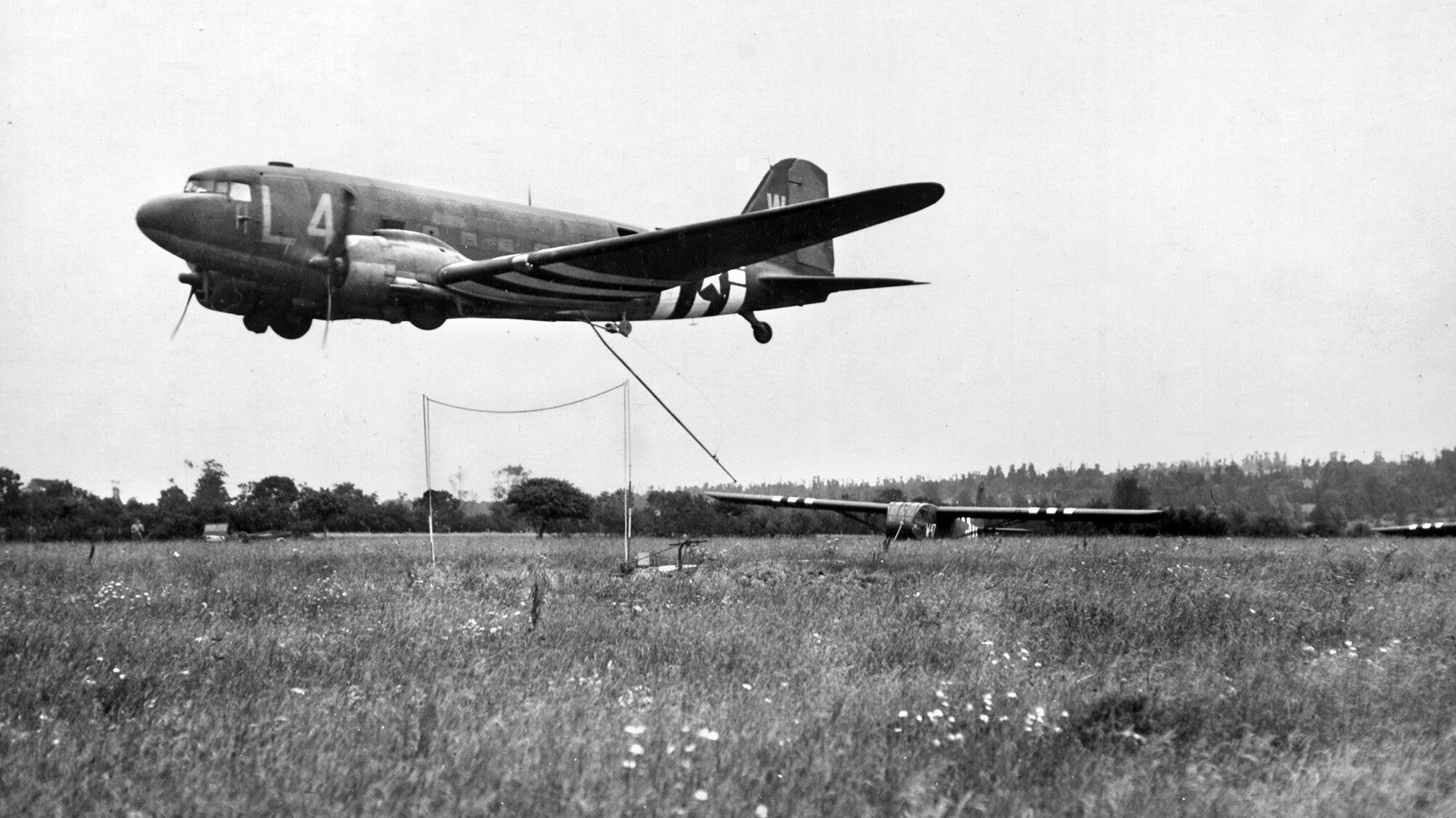

Arnold ordered the study of combat gliders three years later, with the notion that they would deliver troops and light armament to the battlefield, that glider pilots would be the Sherpas of World War II.

The glider design approved in 1942 was 48 feet long with a wingspan of nearly 84 feet—about the size of a B-25 medium bomber. Reinforced fabric wrapped around metal tubing and a wood floor. There were no engines, no defensive guns, and no parachutes for the two pilots. Comprising 70,000 parts, it was a squarish and remarkably strong design with a payload of about 3,700 pounds of men or equipment. Compared to a fighter, its controls were about as sophisticated as a go-kart.

The rushed program was riddled with missteps, false starts, and second-class treatment compared to powered aircraft. Once the Waco CG-4A glider design was approved, manufacturing became a circus. In fact, one manufacturer literally tried to build a glider in a circus tent. Four builders had no aircraft manufacturing experience. Another was accused of “gross mismanagement.” At one facility, 90 percent of glued parts failed.

On one occasion, an instructor leaned against a wing during his lecture and it fell off the fuselage. Tragically, glider wings sometimes separated in mid-flight. In one accident, 10 people, including the mayor of St. Louis and other civic leaders, were killed during a public demonstration when metal components failed under pressure. Later, the glider fleet would be grounded for inspections due to shabby manufacturing in some cases.

Meanwhile, glider-pilot training schools were established in deserts, farm fields and prairies. Many students were “flunked-out aviation cadets, men who were too old for flight crew training … men who wanted adventure … brawlers who detested discipline and lived only for combat,” wrote one glider pilot. Others wrote to their families, glossing over the tragedies of classmates dying when their gliders slammed into the ground.

Finally, in late 1942, the training regimen began to take shape as the first gliders arrived at the schools. Soon students would earn wings with a “G” at its center. Not for “Glider,” the new pilots said. It stood for “Guts.”

America had already been at war for nearly a year. And Nazi Germany had successfully used glider-borne troops to capture Eben-Emael fortress during the invasion of Belgium on May 10, 1940.

America was behind the curve. American glider pilots did not become test pilots for the Army Air Corps until early 1943 as the Allied invasion of Sicily approached. The amphibious assault—the Allies’ largest air-sea operation up to that point of the war—would entail more than 3,000 ships, 150,000 ground troops, and 4,000 aircraft, including 144 gliders. The Allied glider plan for the night of July 9 smelled of disaster from the beginning.

British glider pilots had flown very little in recent months. Many would have to train to fly the American CG-4As in place of the British Horsa gliders. Further, there were not enough British glider pilots for the gliders assigned to the mission. Twenty-four American glider pilots—with no combat experience—volunteered to fly as copilots. They would be towed by American C-47s crews, also inexperienced in combat. More than a few American glider pilots were furious with the mission plan, they later admitted.

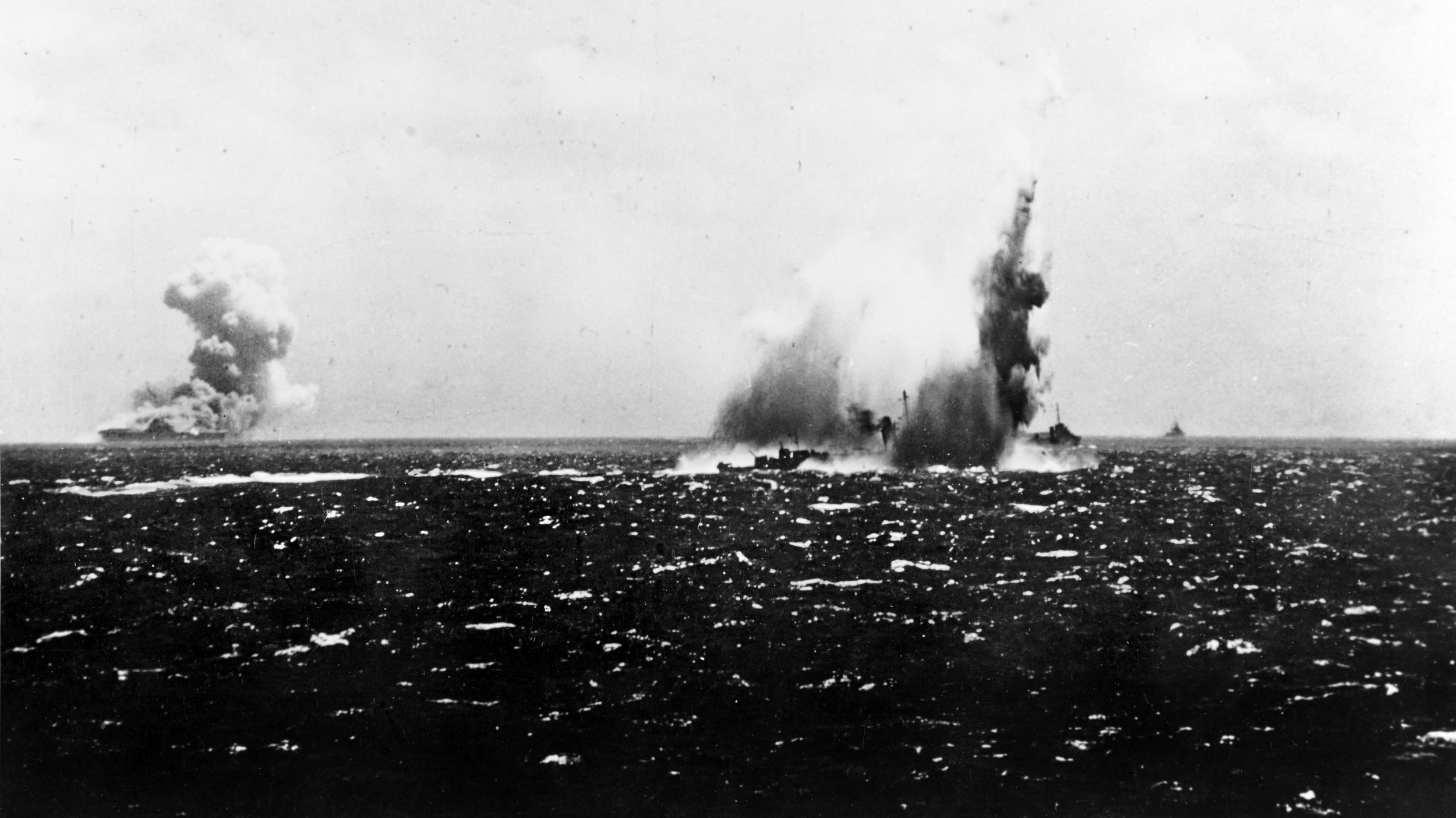

In fact, the mission plan would have frightened combat veterans. The glider pilots would take off in Tunisia at night and in high winds, cross the Mediterranean in stormy weather, release far from shore, glide across 3,000 feet of ocean, pass over the Allied naval fleet, and then the beach under enemy fire from three sides, and finally look for their landing zones.

Disaster unfolded in slow motion. Several tow planes with gliders attached turned back to base shortly after takeoff when glider loads shifted. Three other gliders broke free and vanished into the sea without a trace. Two tow planes got lost and turned back. By the time the remainder approached the wind-whipped coast of Sicily in the dark, chaos reigned.

Debates erupted between glider and tow-plane crews as enemy fire appeared up ahead. Dozens of gliders were released prematurely, guaranteeing they would never make it to shore. Some glider pilots took friendly fire from Allied ships staged offshore during the next day’s assault. The lack of Allied naval communication and coordination infuriated some glider pilots for the rest of their lives.

Long before the sun rose, dozens of glider pilots and their glider infantrymen clung to floating wreckage, debating whether to swim for shore or hold on and wait for search parties. Some swam toward the beach and disappeared. Many drowned throughout the night before the survivors were rescued at dawn.

The glider corps’ portion of Operation Husky had become an unmitigated disaster. Only five of 144 gliders made it to their landing zones; 69 gliders were released too far out at sea to reach the shore. Of 24 American glider pilots, only two made it ashore and six were killed in action. Overall, 605 officers and men were lost, more than half due to drowning.

Although the Allies captured Sicily less than six weeks later, questions about the use of airborne tactics lingered. General Dwight D. Eisenhower, Supreme Commander in the Mediterranean, openly questioned the wisdom of massive airborne operations. It appeared that gliders could be combat-effective only at an exorbitant cost in casualties and resources. Their Sicily performance certainly did not bode well for the volunteer glider pilots as the invasion of the continent loomed.

As Eisenhower contemplated the fate of gliders and the airborne, the surviving glider pilots vented their horror and revulsion in letters and after-action reports.

But the glider forces learned fast. Hours before the 4th Infantry Division waded ashore on Utah Beach nearly a year later on June 6, 1944, nearly 200 glider pilots had landed about six miles inland. Engaging portions of Germany’s 42 divisions along the French coast, slowing the movement of enemy troops, seizing causeways, and delivering supplies for thousands of paratroopers, they were the first of six waves of more than 500 gliders in the first 24 hours of the airborne’s Operation Neptune in support of Operation Overlord.

They arrived on a mission that Air Chief Marshal Sir Trafford Leigh-Mallory had called “unsound in principle,” in part due to their long approach over enemy territory, low altitude, and little hope of surprise after a three-hour flight over the English Channel. Arriving under a full moon or in daylight, he had feared casualty rates of as much as 70 percent in the morning and sunset sorties on D-Day, plus the glider sorties the morning of D+1.

Operation Overlord

Indeed, surprise had vanished as the sky lightened on June 6. As they approached their landing zones, glider pilots braved a pyramid of enemy crossfire. One glider pilot believed a German fighter strafed his glider, shooting away his right aileron control and hitting his tow rope, causing it to unravel. When groundfire blew off the rudder control, he was within seconds of disaster as he separated from his tow plane. Others followed suit.

As Allied troops came ashore a few miles away, it seemed nearly every glider landing resembled a gymnast’s floor routine. Hard landings with a thud. Stopping a glider up on its front skids and risking a somersault. Catching a wingtip and cartwheeling. Caroming off a tree that ripped away a wing. A concussion likely was proof of a “good landing.” For many, battle sounds at first were fuzzy, yelled conversations, unintelligible.

Every field in Normandy became a separate battlefield. Recon photos taken earlier at midday failed to depict the height of hedgerows separating the fields. Instead of the bushes as they appeared to be in the photos, many were five-foot-high dirt embankments that separated the fields. Bramble thickets covered most embankments, along with dense stands of mature trees.

Glider pilots discovered Normandy was a checkerboard of tiny battlefields. Some glider wrecks were not easily spotted from the air. Here and there, a tail revealed where a glider had burrowed into trees. Some gliders were piled on top of others, or flipped onto their tops. Others sat forlornly in a clearing, alone and on their bellies—their wings mangled, tails shot away, as if a giant bird had been shot high in the sky and then had belly flopped onto the ground, spread-eagled and silent. Open doors hinted that perhaps glider pilots and passengers had somehow survived.

Combat brought new horrors. “It was then that I learned the true meaning of the word, ‘terror,’” glider pilot Richard Libbey later wrote. “I could not think … we started moving … the first [glider pilot] I saw was Ben Winks’ copilot.

“Where’s Ben?”

“Ben’s dead.”

“I’ll never forget those words as long as I live. He had so much confidence. He was so sure he was coming back.” Similar nightmares would haunt Normandy glider pilots for a lifetime, shared only in a few letters, journals and at reunions.

Although less than 50 glider pilots were killed in Operation Neptune, the casualty rate among the glider infantry they carried approached 11 percent—a high price. Yet the glider pilots delivered more than 4,000 men to the battlefield, nearly 100 pieces of artillery, almost 300 vehicles, and 300 tons of cargo.

The fabric-covered gliders proved far tougher than most observers would have predicted and their durability kept occupants alive, but at a price. Approximately 97 percent of the gliders in Operation Neptune were too badly damaged to use a second time. “Left to rot,” wrote one glider pilot. Meanwhile, the troops coming ashore with glider support suffered fewer casualties than those who did not.

Yet the lessons were painful. Recon photos were of dubious value. Night missions were nearly suicidal. Releasing gliders at a higher-than-designated altitude dispersed glider landings. Tow planes were vulnerable to enemy fire. Pathfinders were critical to securing landing zones before the gliders’ arrival.

Operation Dragoon—the invasion of southern France—was less than two months away. Would gliders be used then—or ever again?

Operation Dragoon

“Christ what a mess!” Dragoon glider pilot Jack Merrick wrote after the war. “Everywhere I looked, there were gliders in free flight or still tagging along behind tow planes taking evasive action trying not to run into each other…. I watched one glider come whistling in at about 100 miles per hour, hook a wing, and go cartwheeling down the field like a cheerleader at a football game. I later heard stories about a glider in free flight just being missed by a falling jeep and even some being shot at by ships in our own invasion fleet.”

Confusion was the enemy in Operation Dragoon, on August 15, 1944. Long anticipated by the Germans, 2,500 Allied ships would bring 145,000 troops ashore. If successful, the Allies would be positioned to advance on Marseilles, a critical port. A giant pincer attack from the Riviera north and from Normandy southward could cut off Hitler’s troops in western France.

Meanwhile, 10,000 airborne troops would be delivered inland, generally in the Argen Valley, in the span of 15 hours. Glider pilots again would play a key role, with 76 gliders scheduled for an early-morning arrival (Operation Bluebird), followed by 348 gliders about 10 hours later (Operations Dove and Canary).

Once again, mission planning and the fates joined the Germans as enemies of the glider forces. Early morning fog blanketed the landing zone. The Americans’ CG-4As pressed ahead, even as one glider suddenly lost a wing and plunged into the sea. The remainder achieved a remarkable record when 33 of 37 gliders set down in their prescribed LZs (landing zones), likely the best single serial success rate of the war.

But chaos took command later in the day. Deep dust clouds hid landing zones, turning Operation Dove’s approach into a rodeo as planned separation, altitude, and timing all broke down. At one point, dozens of gliders were in free flight in broad, descending circles. As if they were over a drain, drawing closer with each passing second, one glider pilot after another dove out of the converging pattern when he spotted a clearing.

Not only did recon photos fail to distinguish grape vines in some landing zones, but many clearings, farm fields, and cow pastures had been mined, flooded, or studded with upright tree trunks, up to about a foot wide and 10 feet tall—a mutant picket fence nicknamed “Rommel’s Asparagus”—to demolish gliders skidding to a stop.

Most of one glider pilot’s right wing broke away when it collided with another glider as both simultaneously landed, sounding like “an implosion of a giant wooden match box,” and then much of the other wing disappeared in a tangle of vines. The bottom of the glider disintegrated, plowing dirt into the fuselage filled with glider infantry. But it stopped before reaching the trees. “Nice landing, lieutenant,” one of the soldiers yelled to the glider pilot.

Spacing glider serials only 10 minutes apart proved more deadly than a broken-down Germany army that offered minimal resistance. Even more so than over Normandy, inflight delays and changes in the flight plan forced gliders pilots out of their planned approaches and anticipated release at 600 feet. Some were stacked far higher than that, and others nearly overflew gliders that had taken off ahead of them.

Yet, for all the confusion that marked glider operations, Operation Dragoon was an overwhelming success. By the end of the first day, every combat unit of the VI Corps was ashore. Within hours, Allied advancements inland were ahead of schedule against modest German resistance.

Meanwhile, not a single glider that had landed inland could be recovered for later use. Gliders littered the countryside, shattered, broken, and sometimes still containing glider pilots’ equipment and supplies. Yet somehow, only 11 glider pilots were killed and just 32 wounded, a remarkably low casualty rate among the 675 glider pilots.

Operation Market Garden

Operation Market Garden in Holland would commence only one month after Dragoon, on September 17, 1944. The largest glider mission of World War II, more than 1,900 gliders would need pilots from every corner of America, including some who had just pinned their wings on their chests for the first time.

Like the others before it, Market Garden was a plan riddled with risk—an Allied invasion from Belgium up through eastern Holland near the German border to seize the town of Arnhem and its strategic bridge. If successful, the Allies could then flank the northern end of the Germans’ defensive Siegfried Line, and drive into the heart of the Ruhr industrial region while Allied bombers pounded the gun and tank factories there; it would be a dagger into the heart of Germany. To accomplish that, Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery proposed the largest airborne operation to date.

American airborne troops would seize about 50 miles of Highway 69—a narrow two-lane road—running north from the Belgian border, in two sectors near Nijmegen (82nd Airborne) and Eindhoven (101st Airborne) farther south. That would enable the British Second Army’s XXX Corps to drive from the Belgian border up Highway 69, through Eindhoven and Nijmegen, and link up with the British attacking at Arnhem farther north. Massive glider sorties would support the 82nd and 101st with glider infantry, supplies, ordnance, and artillery.

It was an ominous plan from the beginning. The “go decision” came only a few days before the mission, making it the first major airborne mission of the war without significant rehearsal training. The mission would require so many glider pilots that glider infantry would sit in the copilot seats, after about 10 minutes’ “training” just before takeoff. After crossing the English Channel, two glider approach corridors from the north and south crossed into enemy territory before reaching the landing zones—in daylight and, following more than 30,000 paratroopers, with no element of surprise.

But, beginning on d-day, September 17, 1944, bad British weather and then heavy concentrations of German artillery shredded Montgomery’s plan. For three days, fog and rain plagued the Allied air bases surrounding London and over the North Sea, forcing airborne departure delays, route changes, and cancellations. Meanwhile, on the battlefield, the British assault in Arnhem stalled, the 101st and 82nd met stiff resistance, and glider pilots flew into hell.

Their long approach to landing zones became a war film played in fast forward: flashing images outside the cockpit, the “kha-whumps” of artillery shells, bullets splitting the air inside the fuselage, grisly smells filling nostrils until the movie ended with a glider belly down in a field.

After landing, some glider pilots were horrified at the enemy fire that their infantry passengers had taken. In one glider, an infantry corporal slumped with a hole the size of a softball in his chest. Not far away, three others looked like they had been shot through with a single slug, probably a 20mm that hadn’t exploded before exiting under the wing. The glider pilots’ postwar memoirs laid bare the sorrow and horror of glider warfare in Holland.

On D+1 and D+2, approximately 1,500 intrepid glider pilots delivered infantry, anti-tank, antiaircraft, engineer, and recon personnel to the 82nd and 101st. They braved flak so thick that it reminded one pilot of “crows over a tree.” On D+2, the most brutal enemy artillery fire of the mission forced many to fly lower than expected and risk midair collisions. “Rush hour” in the air forced some glider pilots to be released an untenable 15 miles from their intended landing zones.

At one point, a glider pilot glanced down at the floor near his seat. His glider infantry had lined the bottom of the cockpit near him with their flak jackets, because “if anything happens to you, we’re gone,” said one infantryman. Another glider pilot watched a wing fall away from his buddy’s glider. At 500 feet, it turned nose down. His good friend slammed nose-first into a ditch, crushing everyone and everything inside.

On D+6, the sun finally greeted glider pilots. But Operation Market Garden had failed and the attacking British had retreated from the strategic bridge. The plan had targeted “one bridge too far.”

With no glider command structure on the ground, glider pilots were largely left to find their own way back to base. Some took a few extra days to sightsee, adding to a general reputation of glider pilots as rapscallions. Yet they had delivered 8,500 men into battle as well as 900 tons of supplies. Glider pilots amounted to five percent of the men on the ground at the end of Market Garden, the equivalent of a regiment but with only modest combat training at best.

Meanwhile, letters written by glider pilots who did not return were forwarded to families back home. Others received missing-in-action telegrams, offering a sliver of hope.

Only three months later, a rescue mission would turn deadly over frozen ground.

“Some of the wounded had been in there for days. It looked like the Atlanta station scene in Gone with the Wind.’’ The only glider rescue mission of World War II comprised perhaps its most overlooked operation: the Battle of the Bulge.

Winter had iced the war in December, 1944, along a 75-mile stretch in the Ardennes Forest in the southeastern third of Belgium. Biting winds, temperatures approaching zero degrees Fahrenheit, and heavy snows had arrived. It was a time to dig in, hunker down, and replenish as the weather allowed.

But on December 16, the snow had crackled under thousands of German soldiers’ boots two hours before sunrise. The vanguard of approximately 1,000 German tanks headed west toward the Meuse River in central Belgium, breaking through Allied defenses.

Two days later, the 101st Airborne Division mobilized with only two days’ rations as reinforcements headed for Bastogne aboard almost 400 trucks. They joined approximately 18,000 American troops in the Bastogne area who became surrounded by an estimated 45,000 Germans.

For the first time in World War II, glider pilots would not lead an amphibious invasion in Europe. They would not deliver glider infantry and battle supplies to paratroopers behind enemy lines. This time, rescue was the priority.

After several desperate pleas from the 101st, 11 gliders surprised the Germans late on December 26, delivering surgeons, medical supplies, and tank fuel at 5:30 p.m. Only 40 minutes earlier, the lead tank of General George S. Patton’s rescue troops reached the outskirts of the 101st perimeter.

Once again, mission planning contributed to making the next day one of the deadliest glider missions of the war. There were no trained copilots on this mission when their commanding officer decided the cargo of high-explosive ammunition was too dangerous to risk two trained pilots per glider. They also would fly the same route as the gliders flew the day before, even though command learned at the last minute the route Patton’s tanks had blazed was now a safer option.

Remarkably, only three of the first 25 gliders failed to reach the landing zone. But 18 of the next 25 glider pilots either did not reach the landing zone, were killed, or taken prisoner. Of the last 12 glider pilots in Operation Repulse, eight became prisoners of war. Three others were killed. Only one returned to base.

“You can’t imagine what it was like. You know how a goose feels when he flies over a bunch of hunters and they start shooting?” a glider pilot years asked after the war. “[Flak] so black … it reminded me of a black summer storm cloud,” wrote another glider pilot.

By percentage, the flights to Bastogne on the 27th was the costliest glider day of the war for some units. Thirty-two percent of the glider pilots that day were killed or captured. By comparison, historian Rex Shama noted that of the 2,933 glider pilots in Operations Neptune and Market Garden, 114 were listed as killed or missing, a loss of less than four percent. Losses on December 27 proportionately were eight times greater than World War II’s two largest glider missions to date.

Yet the glider pilots delivered 100,000 pounds of cargo on that final day, and the surgeons and medical supplies they delivered on both days likely saved untold lives.

Glider pilot scars from Operation Repulse ran deep. “Not enough enemy position information furnished.” “Need timely and accurate information on enemy positions and AA.” “No flak suits or parachutes—and we were carrying gasoline.” “Glider operations very poor, no flak suits in glider. Briefing very poor, news 48 hours old.”

Glider warfare remained a work in progress.

Varsity—One Final Mission

In early 1945, the Allies had reached the western bank of the Rhine River. The Western Front now stretched 450 miles from the Swiss Alps to Holland. The inevitable thrust into Germany would come in March, a few miles northwest of the German city of Wesel.

Three Allied armies would ford the river, supported by the U.S. 17th and British 6th Airborne Divisions that would fly over the Rhine to drop troops, supplies, and release gliders about six miles into Germany near the Issel River. Operation Varsity would be the largest ground and airborne assault since Normandy. The airborne assault would include more than 1,800 powered aircraft, 900 American gliders, and nearly 450 British gliders—so many gliders that one would be taking off every 12 seconds for nearly three hours.

Veteran glider pilots flying their last combat mission of the war recognized lessons from earlier assignments. No night flight like Normandy. No multi-day missions over a prepared enemy as Holland had been. Unlike Market Garden, there would be plenty of rehearsal exercises before the real thing.

Regardless, maintaining preordained separation between the serials again proved impossible on March 24, 1945. Clean, clear landing zones remained more wish than reality. Prevailing winds pushed chemical smoke ordered by Montgomery to conceal the river crossing drifted over the landing zones and enveloped visual landmarks.

“Flying blind” wasn’t part of the plan as gliders released from their tow planes, turned in a broad circle like eagles looking for prey, and then disappeared down into the smoke, according to one glider pilot. Some of the most vicious enemy antiaircraft artillery fire of the war greeted the gliders.

Horror abounded. One glider pilot thought he had run over a paratrooper when he landed but learned later the paratrooper had already been shot dead as he had descended. Another glider pilot suffered burns on his right arm, right foot, ear, the top of his head, neck, and face. Nearby his copilot was on fire. He had managed to exit and then had fallen to the ground. He died where he fell. Postwar accounts by the pilots who survived reek with remorse, sorrow, and sometimes survivor’s guilt.

Meanwhile, for the first time some glider pilots had been given ground combat orders. The 435th Provisional Glider Pilot Infantry Company (188 glider pilots) had received additional combat training for roadblock duty the night of March 24. Shortly before midnight, an estimated 200 Germans approached their position.

The firefight erupted when an enemy tank approached their position. Red tracers from every direction revealed positions and targets. Hours later, sunrise revealed 15 dead Germans, more than 20 wounded enemy prisoners, and 80 others taken prisoner after what became known as “The Battle of Burp-Gun Corner.”

Glider pilots paid a horrific price for the successful thrust into Germany. Every nine minutes, a glider pilot on approach was killed by enemy fire or in a mid-air explosion, was crushed in a mangled glider, or died from shrapnel or gunfire. That amounted to nearly 40 percent of all the glider pilots killed in World War II and more than the glider pilot deaths in Operations Neptune and Market Garden combined.

But now “the road to Berlin” was clear. It had crossed Normandy, then up through southern France, and across Belgium into Holland—and now, into the Fatherland. America’s glider pilots had flown at the tip of the Allied spear across the width and breadth of the European Theater of Operations.

In only nine months.

Future Operations?

The invasion of Japan loomed over the western horizon. Soon glider pilots began testing various techniques for landing in rice paddies, a far cry from French vineyards and hedgerows. Hiroshima ended that mission preparation and assured the gliders’ obituary.

A few postwar training exercises and rescues took place, using gliders to supply Canadian troops above the Arctic Circle and to rescue aircrews after plane crashes in Greenland and the Yukon Territory.

But in 1952, the U.S. Air Force’s Joint Airborne Troop Board wrote, “Gliders, as an airborne doctrine, are obsolete, and should no longer be included in airborne techniques, concepts and doctrine, or in references thereto.”

Hundreds of glider pilots had given their lives, nearly equally divided between combat and in training in World War II. In fact, when paratroopers had preceded them into enemy territory alerting the enemy, glider pilots paid a disproportional price from the lack of surprise.

Though many glider pilots resented their lack of post-war awards and public recognition, many were delighted decades later when NASA called its Space Shuttle a “high-tech glider” that slowed from 17,300 miles per hour to 250 when landing. A far cry from combat gliders slowing from 100 to 60 miles per hour under fire.

The innocent young men they had been were long gone, replaced by the hardened, often bitter or haunted survivors they had become. One pilot never forgot the words of a military doctor: “All men who go to war die, son. Anyone who comes back, comes back cheated.”

Only in the last decade of their lives did some glider pilots finally share their combat experience, perhaps sanitized from war’s true reality. “I keep getting flashbacks of things that happened … I had high school friends, college friends, frat brothers, but I never put them close to the category that I do of those glider pilots … courage that you would never believe,” one glider pilot acknowledged decades after the war.

Today, few members of the glider corps remain among us. Yet their legacy remains—in their journals, letters, and sometimes sheepish oral histories—whenever service to America calls for a full measure of guts.

Scott McGaugh is a New York Times bestselling author. His latest book, Brotherhood of the Flying Coffin, from which this article is adapted, is based on WWII volunteer glider pilots’ largely unknown personal accounts of their one-way missions into enemy territory—where they faced unimaginable horrors and brutality, yet survived with courage, camaraderie, and even compassion on the battlefield. For more information, go to www.scottmcgaugh.com.

Heroes all…pilots and their passengers. I had an elderly gent that lived down the street from me. As he grew older, my sons and I would help him with his leaves as he had a wooded lot. One day, as we were talking about history while raking , he mentioned he was a WWII vet. I asked him what he did during the war. Raking and talking at the same time, he casually said that he was a glider pilot on D Day. Trying to honor his privacy, I asked if he would share some of his experiences and his answer was:” …not much to tell, I just did my job…”. That modesty always stayed with me.