Don Williams’ story on the Devil’s Den allows me an opening to write about the Battle of Gettysburg. To the myriad words on the conflict, I add the following. The occasion was, for the North, inauspicious. In the Battle of First Manassas, the Federals were routed, humiliated, and almost utterly crushed. In the Seven Days, they were outmaneuvered and forced to retreat. At Second Manassas they were routed, humiliated, and almost crushed. At Antietam, they threw themselves piecemeal at the Confederates and were bloodily repulsed. At Fredericksburg, they charged against entrenched positions and died in droves. At Chancellorsville, they were totally outfoxed and humiliated.

This is the record the Union men took into the Battle of Gettysburg. It is not so much a wonder that they won, but that they stuck around at all when they heard the Army of Northern Virginia was in the vicinity.

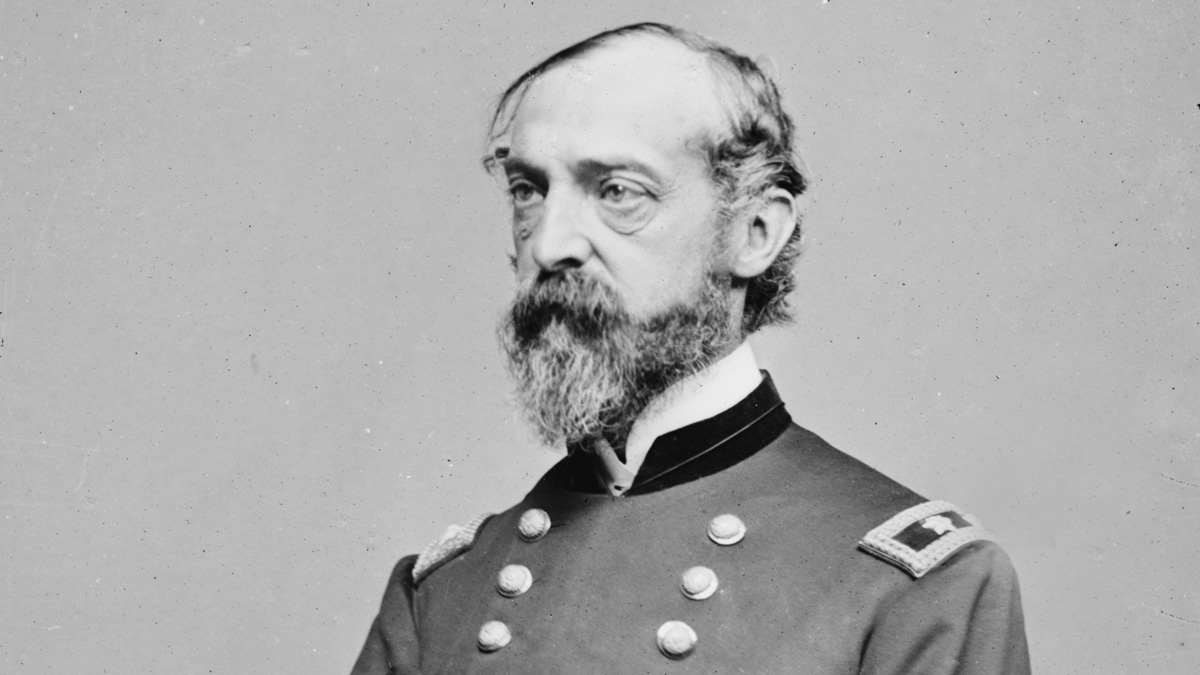

But stick around they did, and with seeming gusto. On the morning of July 1, Army of the Potomac General John Buford, with one cavalry brigade on not particularly good ground, decided to face down Henry Heth’s powerful and advancing infantry division. To the sound of gunfire other Federals under General John Reynolds raced to join. Although not sure of either Confederate placements or the availability of their own reinforcements, Federals threw themselves at the converging Army of Northern Virginia.

Everyone knows the result. Ironies about the battle abound. The Southerners attacked from the north and west; the North defended from the east and south, whereas for most of the war and over its broad range, it was just the opposite. The Federals had the advantage of interior lines, and the South did not, although for most of the war it was the opposite. The Federals, partly out of luck and partly by design, were forced into a defensive position that appeared vulnerable but was actually strong.

In some respects, the battle is so celebrated in American myth and history because it in several ways resembles the whole war in condensation—the three days of the battle can be likened to three phases of the larger war.

On the first day, as in the first phase of the Civil War, the South has ample resources. Their generalship is good and they outfight the Northerners engaged. The Federals are eager but less well prepared. Their generalship is fragmented and discordant. The South is triumphant, but it cannot complete a victory.

On the second day, as in the second phase of the war, Northern generalship improves. The soldiers are more confident of their leaders. Northern resources pour onto the field. But Southern generalship falters, partly on the ineffectualness of the cavalry. Fewer Southern resources can be brought to bear because most are already committed. The resolve of the Northern Cause improves and they can sense success.

On the third day, corresponding to the last phase of the war, Northern resources continue to arrive, but far fewer for the Confederates. Southern generalship is discordant; Northern generalship united, alert, confident. With Southern resources low and the odds lengthening, only a desperate gamble can save their cause. All is given in a final effort, which fails. Further fighting is hopeless.

It is fair to say that before Gettysburg, the Federals in the East never won a major battle and that after Gettysburg they never lost one. Thus its fame as a turning point in the war.

Another final reflection on the battle. In a way, it was an embryo for what life would be like in the United States over the next 100 years. The battle marked the ascendancy—hitherto seriously contested—of the North over the South, and thus of industrialization over agriculture, and of advancing democratization over feudalism and slavery. It marked the beginnings of the apotheosis of Lincoln (partly by virtue of his Address) and the dominance of the Northern point of view in histories of the United States.

Thus Gettysburg became a touchstone for a nation that was literally going to have to recreate itself.

Brooke Stoddard

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments