By Duane Schultz

George Patton knew exactly what he wanted to be from childhood on. “When I was a little boy at home, I used to wear a wooden sword and say to myself, ‘George S. Patton, Jr., Lieutenant General,’” he once remembered.

Although there were missteps and setbacks along the way, mostly of his own making, and times when he was sure his career was over, Patton eventually got his three stars and became a lieutenant general. Then he exceeded his childhood dream and earned a fourth star.

“I must be the happiest boy in the world,” he said, while reminiscing about his childhood. He was born in Southern California on November 11, 1885, to wealthy parents whose sole mission in life seemed to be to spoil the boy, rarely to punish or chastise him for his behavior. And they were not the only ones to treat him this way. His mother’s sister, Annie, who at one time had been desperately in love with Patton’s father, moved in with the family and became “Aunt Nannie,” to baby Georgie, whom she always referred to as her boy. She too never allowed anyone to criticize him or tell him he had done wrong. So thanks to her domination of the Patton family, the youngster pretty much got away with everything.

Aunt Nannie and Patton’s mother moved with him to West Point for the five years he was a cadet (having failed his first year) in case he needed their help. No wonder he was used to being the center of attention and seemed to need to recreate this role for the rest of his life.

But when that role was threatened, no matter the source—or his age—he grew surly, angry, even depressed. When his wife, Beatrice, gave birth to their first child, Patton was 26 years old but found it difficult to play second fiddle when Bea had to devote time to the baby. He became jealous and resentful of the child who, worse to him, was a girl and not the son he hoped for. Another daughter followed, then a son, but he never got along well with the girls; in addition to not being boys, they diverted the limelight from him. He even told his wife, in front of the children, “How did such a beautiful woman like yourself ever have two such ugly daughters?”

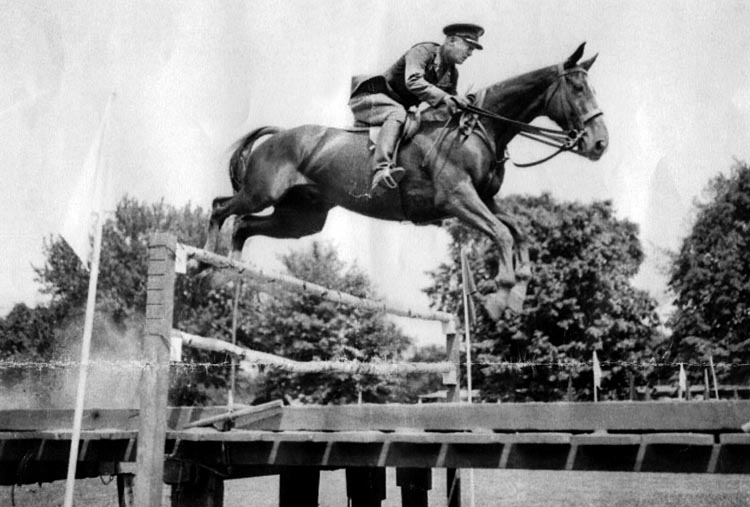

Patton was a strict disciplinarian, even with sports and games. He once tried to teach the children to play tennis, treating them as though they were privates undergoing basic training in the Army. The girls swore to each other that they would never play tennis again. When he tried to teach one daughter how to ride a horse, he yelled at her to get off so he could show her how it was supposed to be done. As he rode off, she was overheard to say, “Dear God, please let that son-of-a-bitch break his neck.”

His son, also named George, was accepted at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point. Patton wrote to him, “We are really proud of you for the first time in your life. See to it that we stay that way.” Obviously, his children were not treated in the adoring, pampered way he had been.

Growing Up Spoiled, Wealthy and Privileged

Patton grew up not only extremely spoiled, but also wealthy and privileged, and his father had no hesitation in giving the boy anything he wanted, including two horses of his own when he was 10 years old. The family enjoyed a life of luxury, which Patton was always able to maintain. In 1910, a year after he graduated from West Point, he married Beatrice Banning Ayer, from a prominent New England family that owned textile mills. The Ayers were also extremely generous in supporting George and Bea.

British military historian Charles Whiting wrote that there was “something arrogant and aristocratic” about George Patton. Whiting went on to describe how no matter how remote and primitive was the Army base to which Patton was assigned, he could “always afford the finest accommodations in the nearest town, motoring back and forth to duty in the latest and most expensive automobile available. [He was partial to Pierce-Arrows, then a status symbol among Hollywood celebrities.] He ran a string of polo ponies at a time during the Depression when the average Army officer of the same rank was lucky to have a single ancient steed at his disposal.”

And when a far less privileged commanding officer ordered Patton to take his polo ponies off the base, he boarded them at a private livery stable at his own expense. “In short,” Whiting concluded, “The Pattons’ private life was aristocratic and upper class; a black-tie affair in the best society.” Of course, such a lifestyle aroused considerable jealousy and resentment among his fellow officers, but that apparently never concerned Patton.

When he was still a poorly paid lieutenant in the Army, Patton bought a 52-foot schooner, had it shipped from New England to California, and spent a month sailing with friends to his new post in Hawaii. He and Bea spent summers in Europe, shipping his automobile along on the same ocean liner on which they sailed; the cost of transporting the car was twice Patton’s monthly salary.

During one of the times he was stationed at Fort Myer, a prestigious Army post across the Potomac River from Washington, D.C., the Patton family rented a house so large it required a housekeeper, governess, cook, and six servants to run. Patton arranged to be chauffeured to the base every day, explaining to his father that everyone else had a personal driver and that he and Bea would not be able to maintain their social standing without one.

Fort Myer was an ideal spot to meet high-ranking military officers and influential Congressmen and cabinet members. Patton liked to say that being stationed there was like being closer to God. It was necessary to have the right clothes and the social standing, bearing, and manners to be accepted by that level of society, and George and Bea Patton fit right in with the tennis and polo matches, fox hunts, steeplechases, horse shows, and lavish parties, as well as hosting their own events for Washington’s prominent leaders. They won acceptance at two of the most important private clubs, the Metropolitan Club and the Chevy Chase Club. Soon Patton bought a second boat, a two-masted schooner moored at the Capital Yacht Club for sailing in the Chesapeake Bay. Because of his fine horses and social cachet, he was invited to horseback riding many mornings with Henry Stimson, who had been Secretary of War during World War I, Secretary of State from 1929 to 1933, and was soon to be Secretary of War again through World War II.

Networking at West Point

Patton’s lavish spending and upper-class ties led to other influential relationships. He had no hesitation in using his money or his family to expedite those relationships. While a student at West Point in 1905, he wrote to his father in advance of his parents’ visit to the Academy, asking him to do whatever he could to cultivate the goodwill of the officers. He told his father that if he could get “on their good side” that would increase his chances of promotion.

In 1939, while in command at Fort Myer, Patton invited the newly promoted Army Chief of Staff, General George C. Marshall, to stay at his own quarters on the post while Marshall’s house was being renovated. Marshall accepted and, as Patton wrote to Bea, apparently the two men had a good time “batching it.”

Patton bought eight solid silver stars from a prominent New York jeweler and presented them to Marshall as a gift for his promotion to four-star general and frequently took Marshall sailing on his schooner. He knew that Marshall was about to make major changes in the Army officer corps, including forced retirement for most officers of Patton’s age.

class of 1909. He struggled in the classroom, particularly due to dyslexia.

On July 27, 1939, during Marshall’s stay at Patton’s quarters, Patton wrote to Bea, who was away with the children, “You had better send me a check for $5000 as I am getting pretty low.” That was a little over three times the average annual salary for a worker in the United States; the equivalent today exceeds $71,000.

It is not surprising, then, that George Patton felt a sense of superiority to others, most of whom he considered beneath him socially, mentally, and morally. While still at West Point, he wrote to his father complaining about his fellow cadets, noting, “I am better than they are…. Someday I will show and make them feel how infernally inferior they are.”

In another letter he told his father, “I belong to a different class, a class almost extinct or one which may never have existed yet.” By his behavior he made it clear to the other cadets that none of them measured up to his own sense of self-worth. Not surprisingly, they left him pretty much alone, considering him arrogant and remote.

Did General Patton Have Dyslexia?

While Patton enjoyed many advantages from childhood on, he was also beset by problems which, while not excusing his behavior, may have influenced it. The first was a learning disability now labeled dyslexia, characterized by difficulties with reading, writing, and spelling. “I am stupid,” he declared as a child. That issue was reinforced when he attended private school at age 12. He could barely read or write. The other students responded to him with laughter, even derision, a harsh response for a boy who had known only praise and flattery. Nevertheless, he had an unusual memory and was able to recite long passages of poetry and prose that his father and Aunt Nannie had read to him. When he finally learned to read, he pored over books for hours on end and could recall every word, particularly those on military history.

Patton biographer Carlo D’Este described additional dyslexic symptoms that affected Patton, including mood swings, obsessiveness, impulsiveness, feelings of inferiority, and a tendency to boast. Dyslexics may feel the need to be as least as good as, but preferably better than, everyone else, which results in a tremendous drive to achieve. In the Army that means becoming not just a general, but a better general than any other.

Patton also suffered a series of accidents, falling off horses and sustaining several concussions. In one incident, two days after a spectacular fall playing polo in Hawaii, he was sailing his yacht off the coast when he turned to his wife in confusion and asked what had happened. He had no idea where he was or what had occurred since the fall; those two days were a blank. He knew bleak moods and intense depression, which worsened with age. He had hoped to be promoted to brigadier general by age 27, but by age 29 he was lamenting the fact that he was not even a first lieutenant. He grew obsessed about showing signs of age.

In 1934, at his daughter’s wedding, his second daughter watched him walk the bride down the aisle. She said that he “looked just like a child who is having his favorite toy taken away. All his determination to remain forever young was being undermined by having a daughter getting married. He was 49 years old, and he had still not won a war…. He looked stricken to the heart.”

On his 50th birthday Patton refused to get out of bed. His worst fears were coming true. His career had come to a halt, his West Point uniform no longer fit, he wore glasses, his hair was thinning and turning gray, and his stomach had begun to bulge. His depression and anger worsened, and he coped with the change by drinking far too much, sometimes making a spectacle of himself in front of his fellow officers.

The pampered rich boy, used to having his own way and feeling superior to others, had only one goal, to become a mighty warrior who would win major victories and earn a place in history as one of the world’s greatest generals. He decided that he had to play the part, to behave the way a successful general would, and so, according to D’Este, he spent “the remainder of his life honing that image by becoming profane, ruthless, and aristocratic. His famous scowl became so successful a part of his persona it seemed as if he had been born with it permanently engraved on his face.”

“I Still Get Scared Under Fire. I Guess I Will Never Get Used to it…”

The noted Patton scholar Martin Blumenson wrote, “Patton was always interested in glory, adulation, recognition and approval. He believed passionately in the virtue of becoming well and widely known. What he wanted, above all, was applause. And for him that meant winning. Not only wars, races and competitions of every sort, but also winning out over himself, overcoming what he regarded as his disabilities and weaknesses.”

Patton once wrote to his father that he was afraid of being a coward. Years later, he took another bad fall from a horse while jumping hurdles and landed on his head. Though clearly shaken, he immediately got back on the horse and led it at a fast pace over the hurdles again. “I did it just to prove to myself that I am not a coward,” he explained.

One day on the rifle range at West Point, it was his turn to work in the pits, raising and lowering the targets and recording where the bullets hit. Suddenly, he climbed up and stood out in the open with bullets flying all around him. He was testing his courage, proving to himself that he was not a coward. He passed the test that day, but there were to be many more. In 1943, he wrote to his wife, “I still get scared under fire. I guess I will never get used to it…. I do hope that I will do my full duty and show the necessary guts.”

Patton developed his dreams of military glory as a child listening to heroic tales of the Civil War, including those told to him by John Singleton Mosby, the famous Confederate guerrilla leader, a frequent guest at the Patton home. Patton’s step-grandfather recounted his own exploits in the rebel army, and his paternal grandfather was a Confederate hero killed in action.

By the time he was a teenager, Patton was reading everything he could find about military heroes throughout the ages. He decided that a man’s greatest glory would be to die on the field of battle, but only, of course, as a famous general. He persuaded himself that would be his destiny, something that had already happened to him in his earlier lives.

George Patton’s Beliefs about Reincarnation

A firm believer in reincarnation, he viewed ancient battle sites as familiar ground on which he had once fought, all the way back to the 2nd century bc, when he was a Carthaginian soldier dying on the battlefield in what is now Tunisia. When he visited that site during the North African campaign of World War II, he knew without a doubt that he had been there before. In whatever era he lived, and he had lived in many in his own mind, he had always been a fearless leader in war.

While Patton’s financial and social positions certainly helped him advance his career, he also worked hard to become a professional soldier, a model leader of men, and a sterling example of physical prowess. In 1912, at the age of 27 while stationed at Fort Myer, he was selected to compete in the modern pentathlon at the 1912 Summer Olympic Games in Stockholm, Sweden. The competition was designed to test fighting ability and endurance and consisted of five events (shooting, swimming, equestrian, fencing, and cross-country). Patton went on a strict diet for two months and refrained from smoking and even drinking while he pushed himself to excel. He earned a respectable fifth place out of 24 contestants and was mentioned in magazine and newspaper articles and Army publications, all of which enhanced his stature and recognition in the Army.

Patton particularly enjoyed fencing. The following summer he went to France to study for several weeks with Raoul Clery, fencing master at the French Cavalry School at Saumur. When he returned home he wrote an article for the Cavalry Journal and an influential report to the Army’s ordnance department about the superiority of the technique he had learned. He was named Master of the Sword for the Army and designed a weapon for the cavalry that was named the Patton Saber in his honor. At the time he was still a second lieutenant, four years out of West Point.

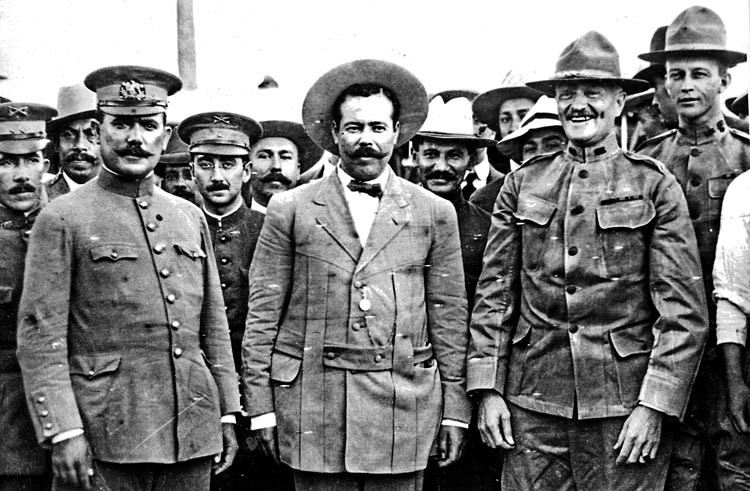

In 1915, Patton used his influence to arrange a transfer to the 8th Cavalry Regiment at Fort Bliss, Texas, under the command of Brig. Gen. John J. “Black Jack” Pershing. Patton quickly received a promotion to first lieutenant and became an aide to Pershing. He went to Mexico as part of Pershing’s expedition to capture Pancho Villa, to keep him and his Mexican bandits from staging more border raids into the United States. In a preview of the armored cavalry warfare to come, Patton led 10 soldiers in three old Dodge touring cars in a blazing gunfight, killing three of Pancho Villa’s soldiers. He draped the bodies over the hoods of the cars and roared into camp with his trophies. The reporters jumped on Patton’s “big battle” for all it was worth. Exaggerated accounts of his great victory over Pancho Villa filled the newspaper headlines for the two weeks. It was Patton’s dream; he was becoming a famous warrior.

In 1917, Patton joined the Tank Corps of the American Expeditionary Forces in France when the United States entered World War I. He saw action in the first American offensive of the war in the Battle of Saint-Mihiel in September 1918, under Pershing’s command. As Patton’s tanks approached a bridge in a barrage of heavy shelling, they stopped when the men realized that the bridge was loaded with demolition charges ready to be set off. Patton went ahead, walking across the bridge, which remained intact. His men quickly followed and captured a large number of German soldiers on the far side.

Weeks later during the Meuse-Argonne offensive, Patton’s tanks and the accompanying infantry forces were stopped by a heavy barrage of machine-gun fire. The men remained pinned down until Patton stood up, waved his walking stick over his head, and shouted, “Let’s go!” Only six of his 100 soldiers followed him, and one by one they were shot. Patton was not hit, but he said later, “I felt a great desire to run.”

He kept on, however, until he was wounded in the thigh. He staggered about 40 feet farther and fell. His orderly dragged him into a shell hole, where he directed the battle for several hours until he finally allowed his men to carry him to an aid station. When Patton’s first major war was over, he had served with glory. By November 11, 1918, he was a full colonel awarded the Distinguished Service Cross and the Distinguished Service Medal.

Setbacks During the Interwar Years

But then came peace. As after every war, the Army was cut drastically. For more than two decades, until the next war, George Patton’s career prospects were bleak. Like most officers after World War I, he was demoted in 1920 to his prewar rank, a captain at age 33. Promotions were slow, even with his connections and decorations. His typical reaction to the boredom and to his thwarted plans for glory was anger. Soon he was behaving in outrageous ways, both at home and on the job, and was far too outspoken and belittling of his fellow officers. He even criticized senior officers in official reports. He had not achieved the destiny he knew should be his, and he was haunted about growing old and losing his mental and physical abilities.

Yet Patton managed to push himself to keep developing professionally, continuing his study of the nature and history of warfare, and he wrote a number of important and well-received articles in Army publications promoting the development of mechanized warfare. He earned high marks and excellent performance reviews at the cavalry’s Field Officer Course at Fort Riley, Kansas, and was one of the few to win the award of ”Distinguished Graduate” at the demanding Command and General Staff School at Fort Leavenworth. Thus, in those difficult years between the wars while Patton was struggling with his personal and career crises, when many people considered him too overbearing, aggressive, and outspoken, he nonetheless received superior ratings and recommendations from his commanding officers.

One report described him as “an officer of outstanding physical and mental energy who … is absolutely fearless and could be counted upon for great feats of leadership in war.” Another evaluation called him “ambitious, progressive, original, professionally studious; conscientious in the performance of his duties…. An officer of very high general value to the service.” And one of his last peacetime reviews, given at Fort Myer, called him a “vigorous, forceful and conscientious officer…an outstanding leader.”

The Coming War in Europe

Patton remained consumed, however, by his unfulfilled dreams of heroism, and he foresaw little hope for any change in the future. But in 1938 his situation suddenly improved when he was ordered once again to Fort Myer. He and Beatrice were able to resume their grand social life and once again mingle with influential people. He received a promotion to the rank of colonel. A year later, George C. Marshall became Army Chief of Staff and began selecting the officers he believed would be the best leaders in the coming war. That was when he accepted Patton’s invitation to share his house while Marshall’s own quarters were being renovated. “A snappy move,” Patton bragged to Bea about the invitation. “Of course it may cramp my style but there are compensations.”

In October 1941, Patton was promoted to brigadier general and given command of the 15,000-man 2nd Armored Division. His picture appeared on the cover of Life magazine, and he was quoted by his grandson as saying, “All that is needed now is a nice juicy war.” Two months later the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor.

The rest is history, just as George Patton had hoped it would be. (Read all about Patton’s exploits in the Second World War inside the pages of WWII History magazine.)

Duane Schultz is a psychologist who has written more than two dozen books and articles on military history. He is currently working on a book about Patton’s controversial World War II experiences. For more information, go to www.duaneschultz.com.