By Eric Niderost

The name Gaius Suetonius Paulinus doesn’t ring across the centuries from the annals of Roman military history like the names of Julius Caesar, Tiberius Nero, or Scipio Africanus. But Suetonius represents the great majority of military commanders throughout history who consistently accomplish their missions yet never succeed so sensationally or blunder so wildly as to be remembered by the general public. Suetonius should be remembered, however, as the perfect example of proper military leadership in the moment of crisis, using ingrained military skills rather than raw emotion and making difficult but necessary decisions in the heat of battle.

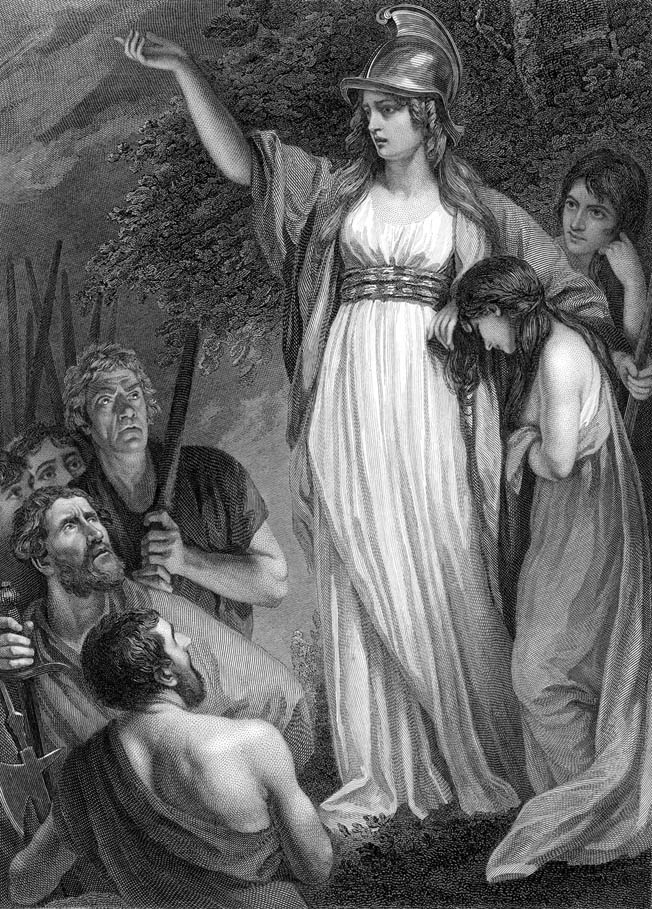

When remembered at all, Suetonius is best known for his action against the rebelling Britons led by Queen Boudicca in ad 60, but he had led a successful career as a typical mid-level Roman officer prior to that. In ad 42, he was dispatched to Mauretania with the rank of praetor to suppress a rebellion; he was soon promoted to the rank of legatus legionis due to the success of his operation. He had the distinction of being the first Roman to cross the Atlas Mountains, and he wrote a description so vivid and detailed that it was later used by other Roman writers in recounting the event. Finally, in ad 59, he received command of Roman Army units stationed in Britain when he was made governor-general of the islands.

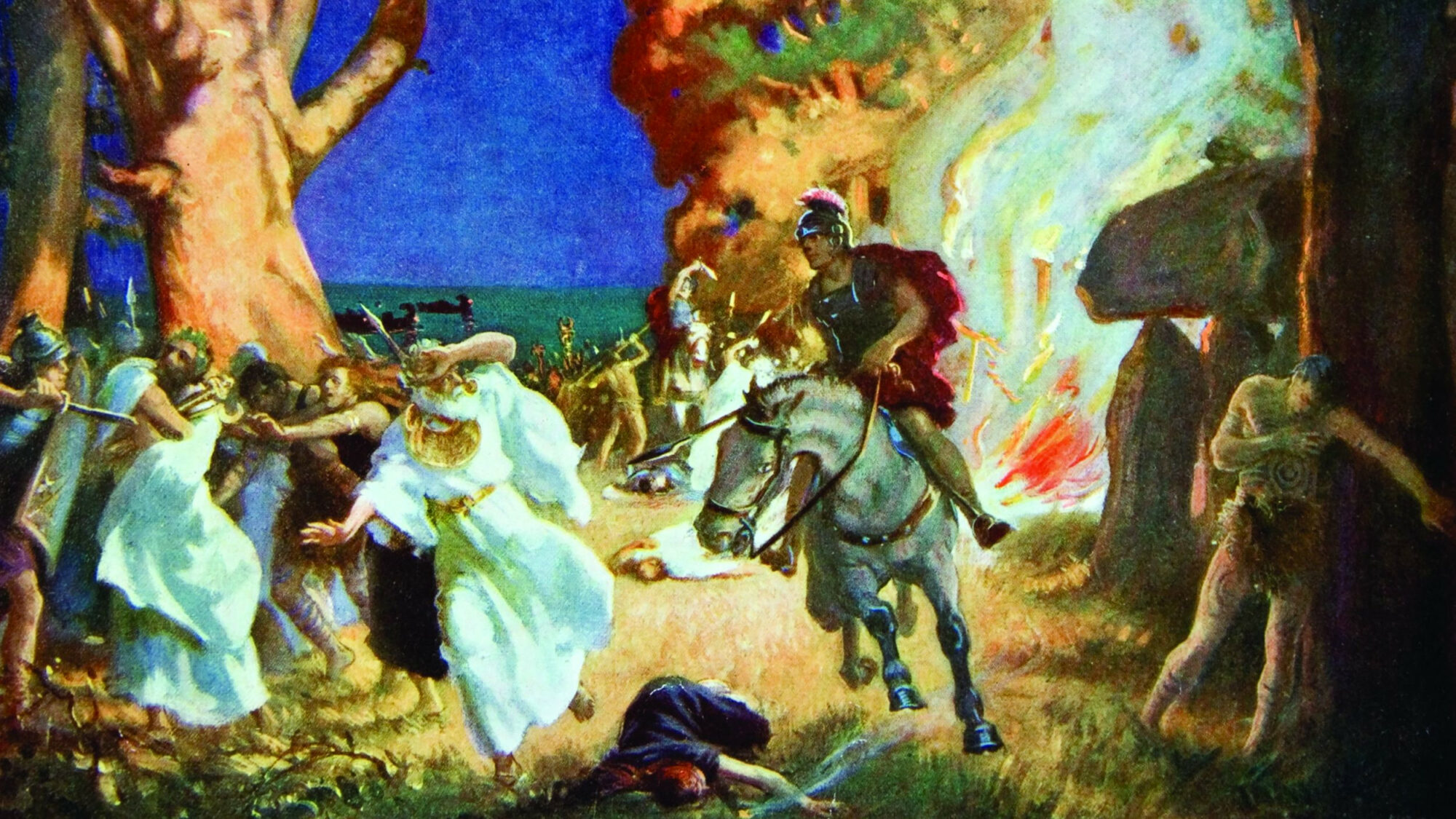

Wiping Out the Druids on the Island of Anglesey

It was in this position that Suetonius took the actions that would make him a model of command and control. One of his duties was to quell the continued disquiet among the indigenous Celtic peoples and make the province a peaceful, wealth-generating part of the empire. As part of the ongoing campaign to control the Celts, Suetonius launched a campaign against their spiritual leaders, the Druids, on the Island of Anglesey in northern Wales. Although the expedition succeeded in eliminating the Druids—Suetonius had them slaughtered and their holy groves of oak trees chopped down and uprooted, in the typical Roman style of conflict resolution—the action unfortunately placed him on the western side of the island just as new trouble was breaking out in the east.

At the same time Suetonius was quelling one rebellion on Anglesey, Roman bureaucrat Catus Decianus was starting another in the area of modern Norfolk. The Iceni, a tribe indigenous to the area, had been allowed to remain autonomous following an earlier failed rebellion in ad 47. Under the complaisant rule of their king, Prasutagus, the Iceni had maintained reasonably peaceful co-existence with the Romans since then, a nominally independent Celtic island surrounded by an increasingly hostile Roman sea.

The Iceni Rebellion

All that changed upon the death of Prasutagus in ad 60. Prior to his death, Prasutagus had prepared a will in which he made the Roman emperor co-heir along with his two daughters, in an apparent attempt to maintain both his family line and the Iceni’s autonomy. Whatever his motives, the attempt failed. Catus decided to utterly ignore Prasutagus’s will and change the Iceni from an independent ally to a client tribe. The Romans confiscated Iceni lands and goods, removed nobles from their lands, and ravaged the area as they saw fit. Catus levied heavy taxes against the Iceni, and private Roman financiers chose this moment to call in Iceni loans. Failure to pay the loans resulted in additional confiscation, depredation, and subjugation of the Iceni and their lands.

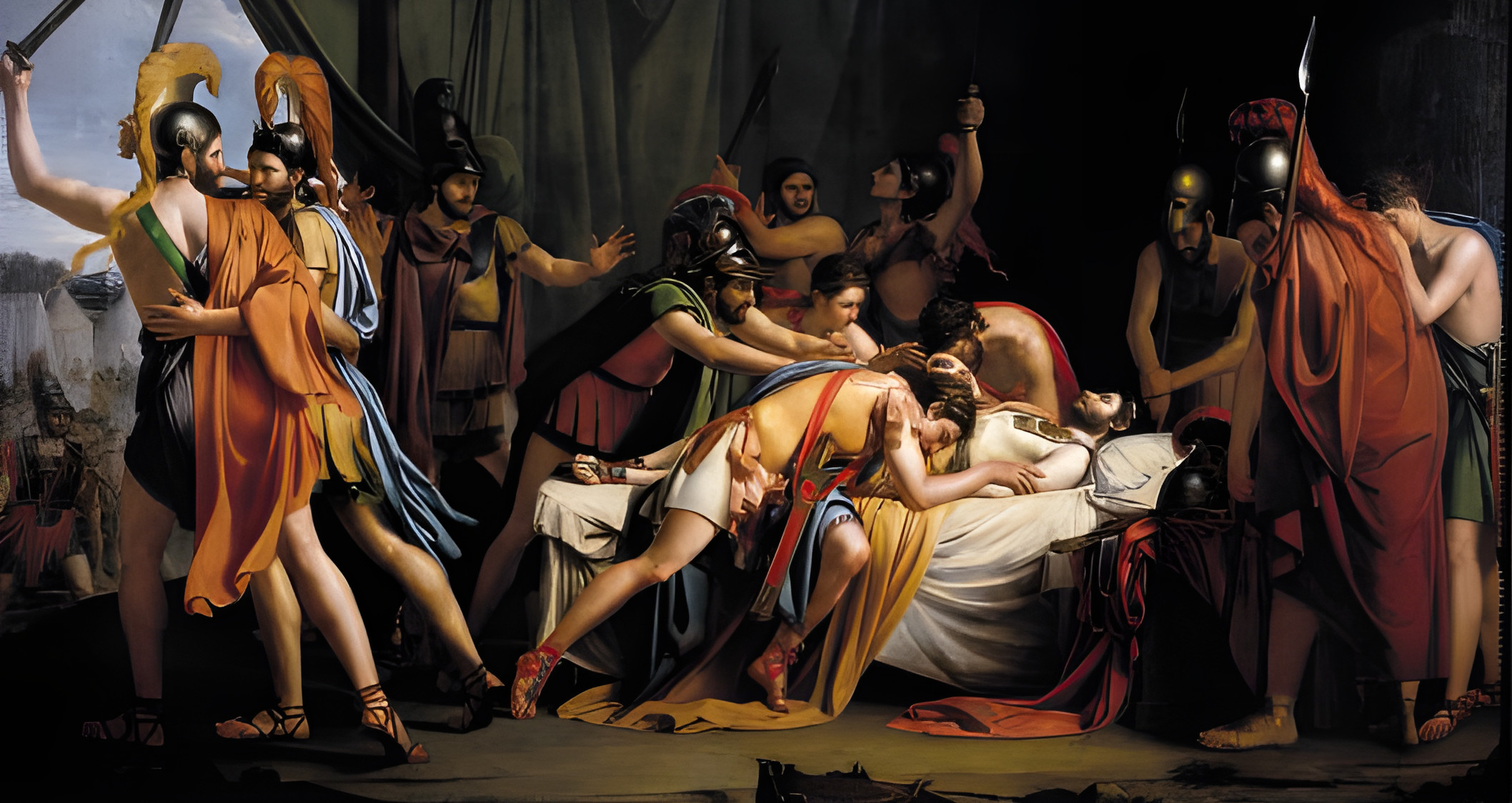

When Boudicca, now queen of the Iceni, publicly objected to Catus over his rapacious treatment of her people, he punished her in the most brutal manner possible: she was stripped naked and flogged in front of her own people while her two daughters were systematically raped by Roman soldiers.

Catus’s choice may have been motivated by Roman chauvinism and a desire to see barbarian people subjugated, by simple greed, or by a political calculation that two young women and a queen could never challenge the rule of Rome, no matter how despicable their treatment. Whatever the motivation of his choice, Catus created a large mess for Suetonius to clean up.

Filled with understandable rage and indignation, Boudicca marshaled the Iceni and Trinovante, another grieved Celtic tribe that had suffered under Roman rule, in a campaign of retribution. Her army marched first to Camulodunum (modern-day Colchester) and massacred the civilian inhabitants there, some of whom were burned alive in the Temple of Claudius, then burned the entire city to the ground. When the commander of the nearby Legio IX Hispana was informed of the destruction of Camulodunum, he reacted by sending what forces he could to contain the rampaging Celts. The Roman column was ambushed and decimated while en route.

Trading Londinium for Time

Suetonius, still on Anglesey, got news of the Iceni revolt. He reacted swiftly to meet the threat. He immediately went to Londinium (London) with a small detachment from his own command, the Legio XIV Gemina, anticipating that it would be the next target of the rampaging Celts. Meanwhile, he ordered the rest of the Legio Gemina to meet him there, and he ordered Hispana, Legio XX Valeria Victrix, and Legio II Augusta to converge with him at Londinium, not knowing that the Legio Hispana had already been defeated by the Celts.

Along the way, Suetonius received one piece of bad news after another. He planned on using superior numbers in his attack against the Iceni, but he was soon informed that a sizable portion of the Legio Hispana had met disaster while en route and would not be able to join in the operation. Then he was informed that the prefect of Augusta, Poenius Postumus, was ignoring the order and refusing to move his unit toward Londinium. Once Suetonius arrived there, he discovered that Catus, the civilian author of all the military woes, had summarily fled the island.

Suetonius was left alone with a small detachment of one legion to face the thousands of the Boudiccan horde. He made the only decision he could: he chose to abandon Londinium to its fate and to trade space for time by falling back toward the advancing Legio Gemina. He ordered all civilians who could move to escape with his unit; those who could not were massacred by the Celts with the same level of ferocity as those in Camulodunum.

Preparing for Battle Against the Celts

Suetonius’s detachment united with the rest of the Legio Gemina and continued falling back in a northwesterly direction along the Watling Road, the direction from which they had come. Suetonius knew that he was vastly outnumbered—there were perhaps 100,000 Celts arrayed against approximately 20,000 Romans—but he had no choice but to stand and fight. It was clear by now that the Celts would not stop until the Romans were entirely pushed off the island. The question was how to do so in a way that nullified the Celts’ superior numbers.

As he marched along the Watling Road, Suetonius looked for the right location for battle and finally found it. He chose a defile that was well wooded on two sides and the rear. The clear space, which essentially made up three sides of a rectangle, was large enough for him to deploy his legion across it, while denying the Celts the chance to flank him or to take his position from the rear. Best of all, the defile would act as a choke point, squeezing the vast numbers of Celts into the same frontage that the Romans occupied, thereby eliminating their manpower advantage.

Suetonius arrayed his forces and waited for Boudicca and her Celtic forces to arrive for battle. Given his tactical training and experience, the outcome of the battle was almost a foregone conclusion. Boudicca may have been an inspirational leader, but she was no military genius, and, while the Celts were ferocious warriors in personal combat, they typically acted less as a cohesive unit than as a collection of surly individuals looking for a fight. Their only military tactic was the frontal assault, a fact that Suetonius knew well and was prepared to use against them.

80,000 Killed

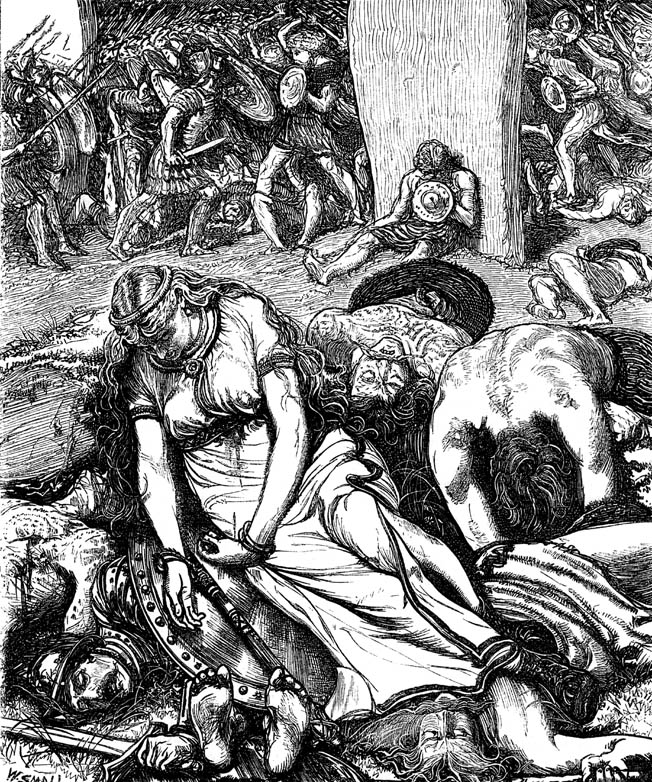

True to their nature, the Celts rushed the Romans with a wild yell, but the Romans, with the discipline that had already won them an empire, stood rock-still until the decisive moment. Hard military training proved its superiority over sheer enthusiasm and emotion, as the Romans waited for the Celts to rush into range of their pila, the specially designed throwing spear used by Roman infantrymen. At approximately 40 yards, the soldiers of the Legio Gemina threw their pila into the onrushing Celtic hordes, causing devastating casualties. The pilum was designed to be a deadly spear capable of impaling a man—especially one like a Celt who wore no armor. The first row of attacking Celts fell like chaff before a scythe.

When the next wave of Celts closed within stabbing distance, the Romans utilized their training and weaponry to obliterate their foe, each soldier acting not as an individual but as a small cog in a great military machine. When he sensed the Celts were close to exhaustion and ready to be counterattacked, Suetonius ordered his legion into a series of connected wedges like the teeth of a saw. The Romans began pushing forward with their shields and stabbing with their short but deadly swords. The Celts had foolishly left their wagon train behind them, blocking the only open escape from the killing box. Inexorably, the Romans forced more and more Celts into an ever shrinking space.

The Romans pushed and stabbed the Celts all the way back to the train, which completely blocked any further movement. The remaining Celtic warriors, women, and children were trapped on the wagons and killed with a merciless fury equal to that shown by the Celts themselves at Camulodunum and Londinium. An estimated 80,000 Celts were killed, compared with fewer than 1,000 Romans. Boudicca and her daughters, no doubt remembering their previous handling by the Romans, killed themselves with poison to avoid a repeat of their suffering.

Suetonius: A Model for Leadership

Suetonius’s actions stand as a model for leadership under the worst possible circumstances. First, he acted swiftly and resolutely when he learned of the rebellion. Despite having just come off a campaign, he immediately ordered his legion back into action, while ordering other legions to converge at Londinium. He knew that delay and procrastination would only lead to more dead Romans, encourage Boudicca, and swell the ranks of her insurgent army.

Second, Suetonius reacted appropriately when confronted by the military maxim that “plans are a list of things that can go wrong.” He had planned to rush to Londinium with his detachment and link up with the Hispana, Augustus, and Valeria Victrix legions, then meet the Celts in battle before they reached the city. When the plan quickly went awry, Suetonius adapted to the situation at hand; rather than focusing on his original plan, he executed a new plan on the fly.

Suetonius knew that he couldn’t simply fling his legions at the Celts and hope for the best, nor could he afford to assume that the Celts were simply a rabble that would flee at the first sight of the Roman eagles. They had, after all, already sacked two Roman cities and mangled half a Roman legion. He had to use all his military knowledge and training, as well as what he knew about the enemy. Rather than panic, he fell back along the Watling Road, knowing that his fleet-footed legionaries could easily stay ahead of the plodding Celts, allowing him time to carefully reconnoiter the battlefield.

Finally, Suetonius understood that the military objective had to be to fully defeat the Celtic army in the field, even if he had to sacrifice Roman civilians at Londinium. There must have been a strong temptation on his part to do something to thwart the Celts before they could reach Londinium. A lesser tactician might have attempted such a maneuver, which no doubt would have ended in disaster. Suetonius knew instinctively that he had to put enough distance between himself and the enemy to find the perfect spot to give battle. He sacrificed the city to win the war.

From George Washington’s elusive maneuvering across Long Island to Robert E. Lee’s fighting retreat turned offensive during the Peninsula Campaign, from the Russians’ sacrifice of Moscow to strand Napoleon deep within enemy territory to France’s stubborn defense of Paris in the Franco-Prussian War, the shadow of Suetonius’s decisions at Watling Road can be seen across the centuries. He clearly deserves to be remembered as the model of effective military leadership under extreme pressure.

The lopsided odds against Suitonius appear to be greater than the numbers you list. Suitonius, by most accounts, commanded between 9-10 thousand soldiers, while the Iceni could have had WELL in excess of 100,000, making his victory as amazing as any.

Gaius Suetonius Paulinus bought himself some time, allowing him to prepare his positions for a frontal attack. I am sure he used the time wisely and ‘dug in’ and intend to prove it. A great deal has been written about this battle, much of it speculation, but the truth of how this site was such a killing field will surprise everyone.