By Bruce L. Brager

Operation Anvil, the invasion of southern France, was originally planned for June 1944, the same time as the Normandy invasion. Anvil was designed to tie up German troops, which might otherwise be sent to Normandy. Eventually, Allied commanders realized that landing craft shortages made simultaneous invasions impossible.

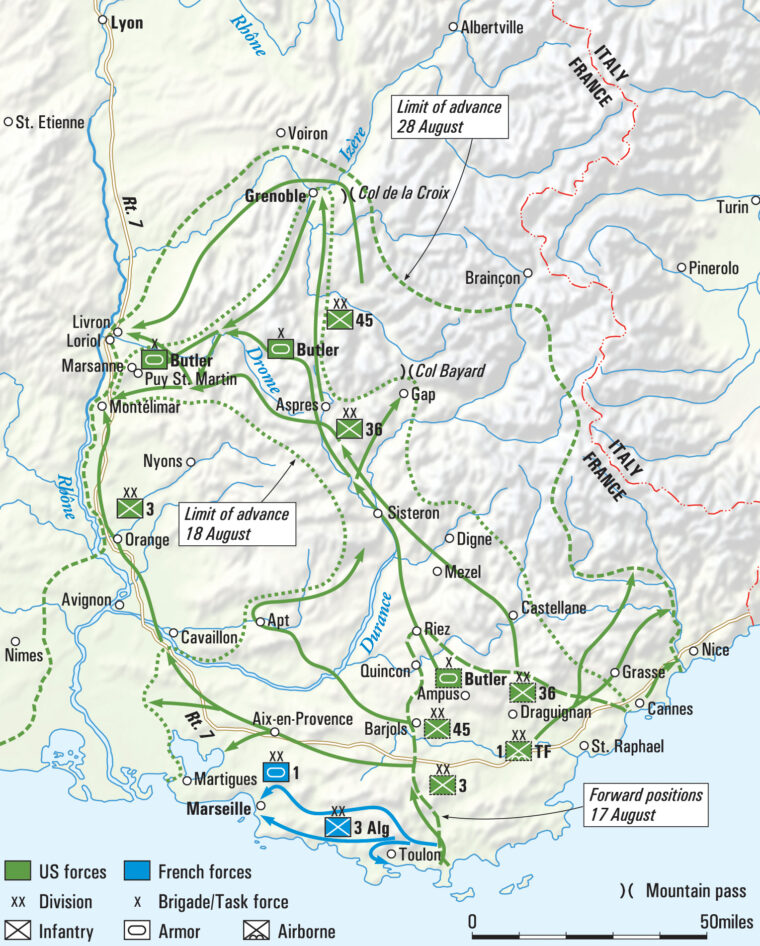

American political and military leaders still supported a second invasion, seeing it as a way to protect the right flank of the advance from Normandy from possible attack by German forces in Italy. The two Allied spearheads would eventually link up to form an unbroken Allied front across France. The southern invasion would capture major French ports, particularly Marseilles, to help land supplies. From an important political perspective, the southern invasion would allow Charles DeGaulle’s Free French troops to play a greater role in liberating their homeland.

The British, however, particularly Prime Minister Winston Churchill, opposed Anvil—whose code name had been formally changed to Operation Dragoon. Churchill favored an attack through the Balkans or expanded support for the war in Italy, and he was politically motivated. The Italian campaign had an overall British commander and any attack into the Balkans would have a British commander. An American general would command in southern France until the force linked up with the main force from Normandy under General Dwight D. Eisenhower, also an American.

Few British soldiers would participate in the Anvil/Dragoon landings. American units would provide the main invasion force, with French units brought in as soon as possible. The American Seventh Army, under the command of Lt. Gen. Alexander M. Patch, would conduct the landings with the three divisions of Lt. Gen. Lucian K. Truscott, Jr.’s, VI Corps hitting the beaches. Maj. Gen. John E. O’Daniel commanded the Regular Army 3rd Division; Maj. Gen. William W. Eagles commanded the 45th Division, with origins in the Oklahoma National Guard; and Maj. Gen. John E. Dahlquist had been brought in from the 70th Division to replace Fred Walker as commander of the 36th Division.

The VI Corps did not control the other units in the invasion. Airborne assault troops, including a British parachute brigade and light artillery battalion, would be commanded by Maj. Gen. Robert T. Frederick, whose old 1st Special Service Force, a combined Canadian-American unit, was now under the command of Colonel Edwin A. Walker. Two French commando units would also take part in the landing. Additional assistance would come from the French Forces of the Interior (FFI), better known as the Maquis. The Maquis had 75,000 men and women in the field, but only about one-third were armed.

The main body of French troops was to come in after the first wave. General Jean de Lattre de Tassigny would temporarily serve as commander of the first French corps brought into southern France. Operations would be upgraded to army level under General Patch. De Lattre was waiving rank so French units could get into the action. When the second French corps arrived, De Lattre would command the First French Army. It would remain under Patch until Lt. Gen. Jacob Devers took command of the 6th Army Group.

German Army Group G, under General Johannes Blaskowitz, occupied defensive positions in the south of France under the overall direction of OB West, the high command for operations in France. The German First Army in southwest France had withdrawn most of its men to the Seine River in early August, and the LXIV Corps was the only remaining element. The 19th Army had seven divisions in the area, but only one reserve division near the invasion beaches. In the days before the invasion, the 11th Panzer Division was spotted on its way to southern France. The Germans had about 30,000 men in the assault area, 200,000 within a few days march, and perhaps another 50,000 also available. The Germans expected an Allied landing roughly when and where it came.

According to the official U.S. Army history, “The choice of assault sites along the Mediterranean coast of France was in large measure dictated by the ANVIL operational concept—to land in southern France, seize and develop a major port, and exploit northward up the Rhone valley.” Three major mountain masses, with natural corridors to the north, rise close to the coast. A direct assault against the cities of Marseilles and Toulon would require the invasion force to traverse poor-quality, heavily defended beaches. The beaches west of Marseille were first rate, but the landing forces were likely to encounter areas the Germans could easily flood.

The best area for an amphibious assault was the coastline between Toulon and Cannes. Toulon was the first major Allied target, but several smaller ports, including the famous St. Tropez, made this area even more attractive. The invasion area was eventually narrowed to the 50 miles between Cape Negre on the west and Theoule-sur-Mer to the east. The three U.S. infantry divisions would assault the inner 30 or so miles of this area, with commandos on both flanks.

The 1st Special Service Force would begin the attack about midnight on August 15, landing on two islands on the left flank of the beach. These islands were expected to hold extensive German artillery positions. Soon after, French commando units would attack both beach flanks. About the same time, the paratroopers were scheduled to drop in the Le Muy area, about 10 miles inland, clear it for glider landings, and block German counterattacks.

The main landings were to begin at the relatively late hour of 8 am in the Cape Cavalaire-Antheor Cove beaches. Daylight was required for accurate bombardment, which the landing forces needed to get sufficient troops and supplies ashore and capture nearby hills.

Two regiments of the 3rd Division would land on the left, capture St. Tropez, and head toward Toulon. Two assault regiments of the 45th would land in the center of the Allied front, take the nearby hills, and capture Ste. Maxime.

The 36th would play a basically defensive role on the right. The division was to advance to the nearby hills, make contact with the paratroopers, and seize the small port of St. Raphael. Only one regiment was scheduled land at H-hour about four miles east of St. Raphael. One battalion would land at Antheor Cove, three miles away. The second regiment would land at the same beach, with the third landing at 2 p.m. between the mouth of the Argens River and St. Raphael. The invasion planners expected that the third regiment would be supported by elements of the 45th Division. If necessary, however, the third regiment could land at the main landing beaches to the east.

The invasion convoys left as scheduled, and things seemed likely to go well. The poetically written “Operations in France for the Month of August 1944,” for the 142nd Infantry Regiment, describes the landing: “A hundred small craft bobbed up and down in the blue Mediterranean within a thousand yards offshore, waiting. Hundreds of other vessels, large and small, were in the vicinity, each with an assigned job to perform…. Looking toward shore from the sea…. spectacular white streamers of smoke fanned out in clusters as phosphorous smoke shells burst in the air. Billows of smoke poured from floating pots laid to form a protective screen…. The three thousand men in the hundred small craft watched all this with anxious interest…. Southern FRANCE was being invaded.”

Every previous landing on the continent had been met by heavy German resistance. In Normandy, the defenders contested the landings on the beaches, and at Salerno on the Italian mainland they had launched savage counterattacks. There was every reason to expect heavy resistance at the Riviera.

The French resistance, the FFI, actually struck the first blow of Anvil/Dragoon. After August 1, incidents of sabotage in southern France made it difficult for Army Group G to maintain communications. The Germans were forced to use combat troops to keep supply routes open to the Riviera since rail and phone lines were regularly cut. Army Group G had a great deal of trouble communicating with OB West near Paris and with its units on the Atlantic coast. The mountains made it difficult to communicate by radio. The FFI had become so aggressive that the Germans could only move large, well-protected convoys along the highways and railroads in southern France. By August, General Blaskowitz considered the FFI as being an effective army in his rear.

The commander of Task Force Butler, an ad hoc pursuit force General Truscott had created, wrote, “The German dread of the Maquis came to the surface continuously during our race into the interior. Really, some of our adventurous young officers became quite persuasive salesmen. Many and many a garrison was taken after a few shots—an American advanced under a white flag and a parley. If the German commander could be convinced that he and his force would become American prisoners, and not be turned over to the French, surrender usually was accomplished forthwith.”

By the time of the invasion in southern France, the Germans only had effective control over the Rhone Valley, the Carcassone Gap, and strips along the Atlantic and the Mediterranean. Extensive strategic Allied bombing contributed to the German confusion by destroying most bridges over the major rivers. Tactical bombing and shelling, however, did not heavily damage German defenses in the landing area.

Airborne landings in the early morning hours began the actual invasion, as had been done in Normandy. Aided by cooperating French resistance forces and commandos landed by sea, the paratroopers succeeded in cutting off most of the invasion beaches from reinforcements.

Task Force Butler’s commander later wrote, “The airborne operation was highly effective and so disrupted communications in paralyzing the [German] 62nd Corps headquarters (the enemy was forced to destroy his radio the first day) that [the German] Corps lost track of what was happening on the beaches.” Indications are, however, that German commanders were not fooled by deception measures, including dummy “paratroopers” similar to those used in Normandy. The attack on the beaches themselves opened with a naval artillery barrage. Two of the three assault divisions, the 3rd and 45th, experienced little significant resistance to their landings. By the time August 15, 1944, was over, the 3rd Division had entered St. Tropez, but found it already had been liberated by the FFI and paratroopers dropped in the area by mistake. By the end of the day, elements of the 3rd had linked with elements of the 45th Division which did not get as far inland. However, it did not require the services of its third regiment, the 179th Infantry, being kept in reserve. A platoon of the 45th Reconnaissance Troop met up with airborne units south of Le Muy.

The 36th Division did not have as easy a time. Four initial color-coded beaches had been selected near the French city of St. Raphael—from east to west, Red, Green, Yellow, and Blue. Yellow Beach would have been an excellent landing site but the troops would have had to go into an estuary and contend with heavy German fire from behind as well as in front. Regimental records for the 141st Infantry report, “The area around the bay was so heavily fortified and its waters so extensively mined that no attempt was to be made to assault the beach.” This beach would be flanked and attacked from the rear. When it was taken, engineers would prepare the beach for landing supplies.

There was little resistance on most beaches that day. Still, an amphibious landing was an unforgettable experience. A history of the 141st Infantry Regiment describes their landing: “Now we were 2000 yards offshore and the great rocket ships began to send their screeching cargo into the air. The sea was rolling lightly and the increased speed threw a fine salt spray into our faces. At 1000 yards the din of thousands of rockets and the shells crashing into the beach ahead become a steady roar in which the concussion caused by no single shell or group of shells could be heard. Now the water became rough and the boat lurched violently from side to side.”

The 1st battalion of the 141st Regiment was the only one to use Blue Beach, the farthest to the east. “The regimental combat team had been split up to assault two separate beaches,” reports the 141st’s history. “The 2d and 3d Battalions assaulted GREEN beach while the 1st Battalion assaulted BLUE beach. Neither GREEN nor BLUE beaches could be called beaches in the technical sense of the word. An extremely narrow strip of rocky shale separated the water from steep embankments directly to the rear of both beaches. Beyond the coastal highway and railroad which paralleled the shoreline along the bluff above the beaches, the terrain ascended in heighth [sic] to high hills, which in turn arose into a mountainous sector to the north. The entire shore area was dotted with villas, hotels and resorts of the famed Riviera “Côte d’Azur.”

The area was also dotted with German defenses, including, according to the regimental history, “pillboxes … in advantageous defensive positions flanked by trenches. Other than the narrow beach, all portions of the land bounding the narrow inlet comprised rocky cliffs.”

The 1st Battalion of the 141st met some resistance but managed to quickly seize high ground overlooking the beach and capture 1,200 German prisoners. The battalion won a Presidential Unit Citation for these actions. The other two battalions in the 141st landed on Green Beach just after 8 am, against light resistance. “The beach line was a sight to behold. The Navy had done a superb job. The only remaining signs of the barb [sic] wire entanglements was a picket here and there,” reported the 2nd Battalion of the 141st. These battalions quickly took the high ground near this beach.

The post-war regimental history continues, “For most of us the memory of D Day in southern France is not too unpleasant. It had been a spectacular show. We had suffered few casualties and our regiment had taken the beach, over which [almost] the entire division had landed, before midnight on D Day. Almost to a man we liked the first impression of France. D Day was warm and sunny and the reddish firm soil was a welcome contrast to the powdered ankle-deep dust of Italy.”

The 143rd Regiment started to land on Green beach at 9:45, followed soon after by division commander Dahlquist and his staff. They planned to watch the 142nd landing on Red Beach several miles to the west and assist if needed. The 2nd Battalion headed directly toward St. Raphael, but encountered stubborn resistance from several German strongpoints. By 2 pm, its lead elements still had not reached St. Raphael.

The Red Beach landing was to take place several hours after that on Green Beach to give the 143rd time to head west and take the heights dominating Red Beach. The division was eventually supposed to occupy a line on the right flank of the Corps, with a 12 to 15 mile depth inland. Red Beach, however, was the most heavily fortified of the assault beaches. It was later discovered that most of the defenses of Green Beach had been removed to strengthen those of neighboring Red Beach. Heavy bombardment and the use of drone boats filled with explosives failed to sufficiently clear obstacles from the beach. At one point, one of the radio-controlled drone boats, loaded with explosives, reversed course and headed straight at the invasion assembly—to the distress of everyone watching. Fortunately, it turned again and ran aground on an inlet near Red Beach without exploding.

The 142nd’s records report, “RED BEACH was the obvious place to land in this coastal sector and its defenses had been stoutly organized by the enemy. A broad sandy beach was near the small port of ST. RAPHAEL and the town of PREJUS. Access to it was essential for the quick follow-up of supplies and equipment which must accompany any invasion force, and in this particular facilitate the intended drive of the Army Northwest in the ARGENS river valley to cut off the ports of TOULON and MARSEILLES…. The alternate plan anticipated the possibility of the 142nd Infantry landing behind the 141st and 143rd on GREEN BEACH. An apparent disadvantage lay in the fact that it hardly seemed feasible to land a whole Division with the necessary armor and vehicles over the one rock-enclosed beach.”

The 142nd was finally scheduled to land on Red Beach at 2 pm Colonel George E. Lynch, the regimental commander, radioed his leading battalion to ask about the delay and learned of the poor performance of the drone boats.

At 3:15, the commander of the naval assault on Red Beach, Rear Adm. Spencer Lewis, ordered the landing craft to head to Green Beach. General Dahlquist ordered the 142nd to land on Green Beach. St. Raphael and Red Beach were captured from the rear within two days.

Lieutenant General Truscott was watching the planned Red Beach landing. He thought the bombardment was going well and was shocked to see the landing flotilla first stop and then head back out to sea. His boss, Seventh Army commander Patch, and overall Navy commander Vice Adm. H.K. Hewitt, shared Truscott’s feelings. Truscott later wrote, “Then, while we watched, helplessly, to our profound astonishment the whole flotilla turned about and headed out to sea again. Hewitt, Patch and I were furious.” Truscott, in fact, threatened to relieve Dahlquist or court- martial Colonel George Lynch, the commander of the 142nd Infantry, if either of them had ordered the diversion. in his 1954 memoirs, Truscott wrote that the diversion and the apparent delay in capturing Red Beach and St. Raphael set back the schedule for the whole operation.

“It was in fact almost the only flaw in an otherwise perfect landing,” wrote Truscott. “Failure to carry out this delayed landing as arranged was to hold up the clearing of Beach 264A by more than a day…. It was in my opinion a grave error which merited reprimand at least, and most certainly no congratulations. Except for the otherwise astounding success of the assault, it might have had even greater consequences.”

Others disagreed. A recent history of the invasion concluded that Truscott’s criticism could have been unjustified. Lt. Col. Fred W. Sladen of the 36th Division wrote in his dairy: “August 17, 1944: Red Beach is finally opened this evening. Good thing we didn’t land there, mines by the thousands and casements and underwater mines and obstacles. We would have taken heavy casualties.”

A member of the division, who later wrote a history of the 36th Division in the last year of the war, also quoted General Tassigny as supporting the decision to switch beaches. The same division veteran offered his own opinion: “The diversion was correct, the decision to do so was correct, and the results were more than satisfactory.”

Lieutenant Colonel Lynch later said he felt his regiment would have been so damaged by a Red Beach landing, that it would have been unable to meet most of its later objectives. The diversion did not hurt Lynch’s career, as he eventually retired from the Army as a major general. The diversion came as a surprise to the Germans. The 142nd’s Record of Operations reports, “A [German] CORPS staff officer admitted that they had never imagined that we could or would attempt to land a whole division on GREEN BEACH.”

By the end of the second day, as the poetic clerk of the 142nd phrased it, “The beachhead was now secure and our forces were rapidly fanning out beyond. The invasion success was won with lightning suddenness and meager casualties.” The controversial diversion had worked and left all regiments of the 36th Division in excellent shape for the work that followed. With the amphibious aspect of the operation completed, the 36th Division was positioned for more conventional land operations. The “blue line” of the initial bridgehead was reached, and Truscott issued new attack orders before dark on August 16.

The two primary French Riviera ports, Marseilles (the largest in France) and Toulon, were taken by French divisions serving with the Seventh Army on August 28, far sooner than expected. The port facilities were repaired and put into service as major supply avenues for the entire Allied effort. On August 17, Army Group G was ordered to pull back to the tough Vosges Mountains. The Allies knew about these orders almost immediately.

The rest of August and a good portion of September consisted of a giant race, sometimes hindered by the need to overcome supply problems. “Our vehicles are too few in number for what we have to haul,” one American company reported. The desperate race was an attempt to stop the withdrawing German forces from reaching stronger positions in the mountains along the German and Swiss borders.

The German coastal defenses of southern France were undermanned, as many troops had been withdrawn to fight the Allied effort in Normandy when the Germans finally realized it was the main invasion. Hilly terrain focused this withdrawal to the roads running up the Rhone River Valley. “With the disorganization of the Germans and their attempt to withdraw up the RHONE valley the campaign developed into a fight for the valley and control of road nets,” wrote a company historian in the 142nd Regiment. “With great mobility, units were maneuvered on the flanks of the enemy, destroying their convoys and large quantities of materiel and personnel.”

Apparently the shortage of vehicles among American formations was overcome before August 22, when Task Force Butler and elements of the 141st Infantry arrived at Montelimar.

The Germans were withdrawing their troops in southern France back to the Vosges Mountains. Intelligence reports indicated that they were not going to move troops from Italy to southern France but would continue to mount a strong defense north of Rome. Lt. Gen. Patch, commander of the 7th Army, planned accordingly. With no concern about his flanks, Patch could use virtually all of his forces in as rapid an advance as possible up the Rhone River Valley. Patch wanted to get ahead of the Germans, block their path, and force them to attack at places the Americans chose. One such place was just north of the city of Montelimar, 120 miles from the invasion beaches, 80 miles inland from the coast.

The Rhone River Valley and its two major highways run virtually north to south. It was the quickest, most logical route for a retreating German force, especially one protected by the powerful 11th Panzer Division, which was heading to the area. The valley has one particularly significant characteristic. It varies in width. Usually a broad plain, with space for maneuver along its two main highways, the terrain frequently narrows. These bottlenecks are obvious points for defending the valley or stopping a retreating army. Montelimar itself originated as such a defensive position, a Roman fortress at a particularly narrow spot with rugged hills and cliffs near both banks of the river. The area came to be called the Montelimar Gate.

Task Force Butler had been created as a rapid-movement force to try to block the German retreat. In order to leave him with an exploitation force if French armor was taken from his command, about a week before the Anvil/Dragoon invasion VI Corps commander Truscott had planned to put together a provisional Armored Group from elements of the corps. Placed under the command of Brig. Gen. Frederick B. Butler, the deputy commander of VI Corps, the force consisted of a motorized infantry battalion, 30 medium tanks, 12 tank destroyers, 12 self-propelled artillery pieces, and a light cavalry squadron with armored cars, light tanks, and trucks. While Task Force Butler has been described as balanced and mobile, it was not particularly strong, with a complement equal to somewhere between one and two regiments.

By August 19, Butler’s force (to which had been added a battalion of the 143rd infantry) was already speeding northwest, preparing to swing around in front of the Germans. The force reached Sisteron, about halfway to Montelimar, by noon. About this time, Patch told Truscott to have a division ready to advance northward, in the general direction of Grenoble. Truscott ordered Dahlquist to have the 36th Division ready to move early the next day. Truscott expected that at least one regiment of the 36th would reach Sisteron by the end of that day. Butler was told to await Dahlquist, but also to continue patrols westward to seize the high ground north of Montelimar.

Butler never got this message. The mountains, which had interfered with Army Group G and 19th Army radio transmissions, affected American communications as well. The only instructions Butler received on the night of the 19th stated that the mission of the task force was unchanged—reconnaissance northward. Shortly before midnight, Butler reported that he intended to continue in the morning. He also reported a shortage of fuel and asked for further instructions, particularly whether he should head north to Grenoble or west to Montelimar. Butler was uneasy remaining stationary at Sisteron, within enemy territory. The FFI had reported a strong German force at Grenoble, and one within 30 miles of Task Force Butler. Butler was oriented toward a northward advance, but sent his operations officer by liaison plane to corps headquarters for more specific orders.

On the evening of the 20th, Brig. Gen. Robert I. Stack, assistant division commander of the 36th, arrived with part of the division headquarters and the remaining two battalions of the 143rd Infantry. The operations officer had returned with the news that further orders would be coming that night. Stack reported that the 36th Division was headed north, with the 142nd now 35 miles away. The 141st would follow the next morning. Stack warned Butler, however, that the division was still being hindered by shortages of fuel and trucks, and he did not know when it would arrive. The 143rd was to head for Grenoble the next morning. Stack thought this was the most logical move for Butler.

Radioing Dahlquist that evening, Stack relayed instructions for Butler to stay in the area of Sisternon until most of the 36th had arrived. Several hours later, after speaking with Truscott, Dahlquist told Butler to stay in the area and cancelled the move to Grenoble. Finally, at about 8 pm on August 20, Truscott ordered Butler to move as rapidly as possible to Montelimar at dawn the next morning, seize the town, and block the German route of withdrawal. The 36th Division would follow as quickly as possible.

A slight change in the written orders, received by Butler early the next morning, told him to seize the high ground north of Montelimar but not the city before dark the next day. Two battalions of corps artillery were being sent, but only one infantry regiment with supporting artillery and other units, the 141st, was specifically ordered to immediately join Butler. The rest of the division would not be ordered to the Montelimar area until 24 hours later. Dahlquist would take command as soon as he arrived on the scene.

Butler’s force, which had been spread out and oriented north to Grenoble, was regrouped on the morning of the 21st. Some of his force had to be left to secure his rear until the 36th Division elements could arrive. By the end of the day, however, the bulk of Butler’s force was within 13 miles of the Rhone River at the town of Crest.

Crest was the northeast corner of what came to be known as the Montelimar Battle Square. Boundaries for this area were the Drome River on the north, the Rhone River on the west, the Roubien River on the south, and the implied line north south from Crest to the Roubien on the east. The area alternates from flat farmland to rugged, hilly country. Route N-7 runs through Montelimar, two miles from the Rhone, and then continues up the valley. A secondary road, D-6, passes through Montelimar, then cuts into mountainous country before rejoining N-7 about 15 miles north of the city. Railroad tracks run on both sides of the Rhone, with another road paralleling N-7 to the west of the Rhone.

Butler’s men reached Marsanne, in the center of the “square” and blocking D-6, late on the 21st. The advance party, under Lt. Col. Joseph G. Felber, recognized that Hill 300, next to N-7, with a clear view of the other Rhone arteries, was the key terrain feature. Unable to occupy the whole ridge, Felber set up outposts, roadblocks, and other positions. Germans were already passing through on the road. A light armor and infantry roadblock was chased back into the hills by a German attack at dusk. The Americans also destroyed the N-7 bridge over the Drome in the northwest section of the disputed area with no resistance from the Germans.

On the north bank of the Drome, light armor sent west from Crest spotted a German truck column fording a stream. Fifty of these trucks were destroyed before the troop was ordered back to Crest to protect the roads to Puy St. Martin in the middle of the “square.”

Just before midnight on August 21, Butler radioed Truscott to report the task force’s arrival at the objective area. Butler said that his forces were thinly spread out but, with more artillery and a regiment from the 36th Division, Butler thought he not only could hold out but could successfully attack Montelimar the next afternoon. By the next morning, Butler’s force had received neither reinforcements nor supplies.

The Germans struck first the next day. Units attacked north from Montelimar, taking Sauzet and forcing an American outpost back into the hills. This was just a feint, however. Larger German forces attacked from south of the Roubion River, advancing on Puy St. Martin and Marsanne behind Butler’s defenses. Puy was occupied that afternoon, cutting Butler’s supply line back to Crest and Sisteron. Fortunately, Butler’s unit left to guard his rear at the town of Gap had been relieved by the 36th and arrived in time to successfully counterattack into Puy.

Butler thought the German attacks were still only probes to determine his strength. He expected a far larger attack the next morning, August 23. No part of the 36th arrived during most of the 22nd, just Butler’s own men from Gap and the Croix de Haute pass and the two battalions of corps artillery. The task force was also beginning to run out of tank and artillery ammunition. About 10 pm on the evening of the 22nd, the 2nd Battalion of the 141st Regiment arrived. The regimental operations report later stated, “The many miles covered by the regiment in the previous two days had placed a severe strain on the Service Company. The drivers received very little rest and the supplying of gasoline, rations and water for all units of the combat team proved to be a most difficult and arduous task.”

Generals Truscott and Butler would be critical of the 36th Division and its delayed arrival at Montelimar. Butler later wrote that at Montelimar, “even had the 36th Division swung in behind me rather than continue north to Grenoble the effectiveness of my position would have been enhanced,” and referred to the “slowness of the relief at Gap” by the 36th. An aide to General Truscott even wrote in his journal for August 21, 1944, “36th fouled up.”

The U.S. Army in World War II, also known as the Green Book series, relates, “The lack of reinforcements reflected American indecision. Throughout the day and evening of 21 August neither Patch nor Truscott had been willing to make Montelimar the major effort. They were still unable to predict when Toulon and Marseille would fall, or confirm the beginning of a complete German withdrawal up the Rhone valley.”

Truscott finally ordered Dahlquist to start moving toward Montelimar at 11 pm on August 21. That evening at 9 pm, the 141st was in Digne, 80 direct miles southwest (more by road) from Montelimar. Most of the division was still swinging north toward Grenoble in accordance with its latest orders. Division orders instructed the 141st to move toward Aspres-sur-Beach, on the route to both Grenoble and Montelimar, and still less than halfway toward Montelimar. The 141st itself had just completed, not long before midnight on August 19th, a sharp action in capturing the town of Callian, only 16 miles from the beach.

The next morning, Truscott flew to the area around Montelimar to find out what was causing the delay in movement. He remembered flying to the 36th command post just before noon on August 22. A staff officer of the 141st, present when General Truscott arrived, later recalled that the VI Corps commander’s plane landed on the highway between Aspres and Sisternon, where the 141st was moving, mostly by foot, toward the division Headquarters at Aspres.

“General Truscott got out of the plane and introduced himself. I was traveling in a jeep with [141st Regiment commander] Colonel Harmony. We told General Truscott we were on route to the Division CP to get instructions on our next employment. He got into the jeep with us and we hastened to the Division CP in Aspres. We were met by Colonel Stewart T. Vincent, the chief of staff, who said that General Dahlquist was ‘up front somewhere.’ He had no means of communicating with him. Truscott asked Vincent if he had received the message which he, Truscott, had sent the night before, telling Dahlquist to get the division to Montelimar as quickly as possible, with the mission of blocking the highway. He said that was the key to stopping the German Nineteenth Army. Vincent had no knowledge of the message, but Truscott demanded that the Message Center chief check. The sergeant found that the message had been delivered late the night before to Lieutenant Colonel Fred W. Sladen, the Division G-3 (operations officer).”

Apparently Sladen had not thought to awaken Dahlquist. When Sladen got up the next morning, Dahlquist was gone. Sladen then went to Gap and Grenoble with Stack, the assistant division commander. He appears not to have mentioned the orders to Stack. There is no mention that Truscott had asked to have his orders confirmed by Dahlquist.

“Truscott was bitterly disappointed,” remembered the staff officer of the 141st, “and he turned to Harmony and told him to get his regiment to the west, in the vicinity of Crest, as soon as possible. He then turned to Vincent and told him to get in touch with General Dahlquist by whatever means possible and inform him to get his forces to Montelimar as soon as possible.”

Truscott returned to his command post and sent Dahlquist written orders. He expressed disappointment with the 36th Division’s deployments. According to Truscott’s memoirs, he emphasized that the “primary mission of the 36th is to block the Rhone Valley in the gap immediately north of Montelimar. For this purpose you must be prepared to employ the bulk of your Division. If this operation develops as seems probable, all of your Division will be none too much in the Rhone valley area.”

The 19th Regiment was to replace the 143rd at Grenoble, with the 45th Division eventually assuming responsibility for that area. Truscott also sent a convoy of fuel trucks to the 36th, enabling the rest of the 141st to join Butler. Telephone conversations with Dahlquist—on a line finally opened—stressed the basic orders, though making a few changes in details. The confusion with the 36th finally seems to have been straightened out on August 23, when the division began to shift westward to block the Rhone Valley.

The bulk of the 11th Panzer Division had actually gotten south of Montelimar. The division’s reconnaissance battalion had fought with Butler on the 22nd, while most of its elements were blocking roads leading to the Rhone from the east and the landing beaches. The division was then ordered to move northward, take the high ground around Montelimar, and secure Highway N-7 running northward. The 198th Infantry Division was also ordered to the area. Fortunately for Butler, Dahlquist, and Truscott, the Germans had the same supply problems as the Allies. The first elements did not reach the Montelimar area until August 23, with the rest not expected until the next day, but the Germans still intended to seize the initiative.

The difficult terrain provided one final obstacle to the immediate execution of Truscott’s order and the records of the 141st Infantry describe it: “The country through which the regiment travelled was mountainous, comprising portions of the French Alps. A good highway was available most of the way but the Germans had made enough demolitions to cause numerous detours. The enemy had evidently left the sector very hurriedly as there were many places where effective demolitions could have appreciably held up the motor columns. This mountainous region was a stronghold of the FFI (French Forces of the Interior) and the information and assistance furnished by this force was invaluable. It was extremely improbable that the Allied thrust so far north in a few days could have been accomplished without their aid.”

Fighting started again with the arrival of the lead elements of the 141st. “For us,” as a regimental history of the 141st put it, “Montelimar and the week from August 24th to the 30th was one of the fullest 168 hour weeks of the war.” Colonel Harmony was with the 2nd Battalion and received his regimental assignments from General Butler. The 2nd Battalion was assigned to attack Montelimar itself, with a jump-off point about 5 miles from the city.

Three German probes were fought off during the day. Fortunately for Task Force Butler (formally abolished on August 23, but still together) and the 36th, the Germans also did not have full strength in the Montelimar area. Company A of the 1st Battalion was able to seize the north slope of Hill 300, about five miles north of Montelimar, without opposition.

The main American attack of that day came down highway D-6, through Sauzet, aimed at Montelimar. Troop B of the 117th Cavalry Reconnaissance Squadron moved out with Company F, the leading element of the 2nd Battalion. Tanks and tank destroyers had not arrived in time for the attack. As the battalion commander later remembered, “We reached a point a little more than a kilometer from Montelimar when we got into a heavy fire fight with the Germans…. Our attack was actually brought to a halt by a combination of an intense grass and brush fire and by the Germans.”

Butler had yet not blocked highway N-7, though on the afternoon of the 23rd Truscott ordered all Rhone valley roads blocked. Both battalions were counterattacked that evening and night, but held their positions. However, the Germans began to infiltrate around the units on the maze of area roads. The 2nd Battalion mission changed from an attack on the town to withdrawing to presumably better defensive positions north of the road east from Montelimar. Both units were alerted to expect a German attack the next morning. The rest of the 36th Division was on its way, but still not quickly. Increasingly strong German counterattacks started the next morning. One was against 2nd Battalion.

The battalion’s commander, Lt. Col. James H. Critchfield, later recalled, “At dawn the next morning, we again attacked, with Company F in the lead. We were quite successful and they actually reached and cut Highway 7 just north of Montelimar…. After a while they launched an attack out of the village; the situation stabilized, and turned into a fight that raged throughout the day. I can only describe it as intense…. During the day, we had a series of attacks against us of varying intensity…. Gradually we were forced back into a perimeter defense. Our connections to the rear were very tenuous—we really didn’t have a rear area except for those up near Marsanne. There were no stable lines at this time.”

American units were holding on in the general area, aided by artillery and other supporting elements. However, they were pushed back from blocking N-7, their primary goal in the area. Dahlquist seemed more concerned with holding his position than with any active offense against the German escape route. The 142nd and 143rd, still not in the area, received confusing orders from division headquarters. Truscott spoke with Dahlquist, again reminding the division commander to block N-7. One can only imagine what Truscott would have said if he had learned that a copy of Dahlquist’s operational instructions for the next day, had fallen into German hands. A liaison officer had left them in a jeep, fleeing a German roadblock. Fortunately, all of the 36th Division arrived in the battle square that night.

The complex German battle plan for August 25 called for attacks from six different directions. If all went well, they would be able to surround and virtually destroy the 36th Division and Task Force Butler. Coordination proved impossible, and the attacks had different degrees of success. One battle group from 11th Panzer, formed around a panzergrenadier battalion, attacked eastward along the Drome River from N-7, in the north of the combat area. The attack began just before noon, reaching Grane before 2 pm, about halfway to Crest at the northeast corner of the “battle square.” Other German units seized the town of Allex, north of the Drome, about the same time.

Dahlquist sent what remained of Task Force Butler, a weak battalion with supporting elements, north from Puy halfway to Crest to cover his supply route. Butler sent a tank platoon toward Grane. It was not able to retake the town, but set up a blocking position just outside it. No further German attacks in this area followed. The Germans in Grane seemed content to defend their gains, while their attacks in the southern part of the box had accomplished little.

The main American offensive of that day was an attack directly at Highway N-7. The Hill 300-La Coucourde area, about five miles north of Montelimar, was left unprotected by the Germans for most of the day. However, defending a six-mile front made it impossible for Colonel Harmony to put together a 141st Regimental attacking force until late in the day. About 4 pm, units of the 2nd Battalion, 143rd Infantry, secured the northern portion of Hill 300. The 1st Battalion, 141st Infantry, moved directly at the highway. Elements of the German battle group supposed to be in the area arrived, but were fought off. By 7 pm, an American rifle company (later reinforced by a second company), four tanks, and seven tank destroyers had set up a roadblock. German traffic was again piling up south of Montelimar.

American artillery kept the Germans from assembling for a counterattack until nightfall, but Colonel Harmony was concerned about whether the road could be held. German pressure against the rest of his regiment was making it impossible to reinforce the blocking force. He was having trouble keeping it supplied. The Colonel suggested the force retire into the nearby pass at Hill 300 for the night, blowing up several bridges before leaving. They could return in the morning. Dahlquist vetoed this idea in compliance with Truscott’s orders.

By this time, Maj. Gen. Wend von Wietersheim, commander of the 11th Panzer Division and acting commander of a temporary corps combining the 11th and the 198th Infantry Division, had become annoyed with the failure of his plans and of his men to keep the road open. He organized an attacking force from what he could scrape together near Montelimar and personally led a midnight attack on the roadblock. By 1 am, three of his tanks and six tank destroyers had been knocked out, with the rest of the force dispersed. Wietersheim sent some of his forces to seize the high ground over the highway to prevent an easy American attack in the morning.

When the fighting on the 25th and early on the 26th ended, neither side had done particularly well. Dahlquist had still used little of his strength, with most of the 142nd and 143rd having seen virtually no action. The Germans had opened the road, but that was all they had accomplished. Their forces were spread out, vulnerable to attack at weak points.

On August 26, Truscott ordered the 45th Division to send the 157th Regimental Combat Team and the 191st Tank Battalion north to the Montelimar “battle square” area. Part of the force arrived on the 25th, to be used as the 36th Division reserve. The rest, arriving the next day, stayed at Crest as corps reserve. The 3rd Division was also on its way to the area. No major German units arrived, though part of the LXXXV Corps was still heading toward Montelimar from the south. However, Von Wietersheim asked to be relieved of responsibility for the acting corps command so he could just handle 11th Panzer. Lt. Gen. Baptist Kneiss, commander of the LXXXV Corps, was given control of the Germans troops in the Montelimar area.

The only offensive action Dahlquist planned for the 26th was an attack by Butler through the Condilac Pass to restore the roadblock. The major portion of this attack started in the early afternoon. Butler sent two rifle companies of the 3rd Battalion, 143rd Infantry, over the northern slope of Hill 300. As they neared the highway, they were reinforced by a platoon of medium tanks and some tank destroyers moving on the road directly out of the pass. The attacking Americans ran into Germans both moving up from the south and attacking down from the north, and the best they could do was hang on to Hill 300 after again being pushed off the road. The tanks and tank destroyers withdrew. Efforts by the 143rd in the next few days were also unsuccessful.

The commander of the 3rd Battalion later remembered the battle: “We didn’t have much trouble taking the high ground, but we had trouble keeping it…. Fortunately, we had good artillery communications, and they were blasting the valley. As the Germans attacked over our positions, we called the artillery down on our own location. There was nothing else we could do.”

The Presidential Unit Citation the 3rd Battalion won described the rest of their battle. “The following day, when attacked by an enemy force of battalion strength, units of the battalion fought valiantly to repel the attackers and inflict upon them an estimated 30 percent dead, while other units of the battalion courageously beat off successive enemy tank and infantry attacks from the north.

“The members of the battalion directed thousands of rounds of mortar fire into the enemy, blocking the highway with the debris of destroyed vehicles and trucks.

“On 29 August 1944, the enemy in overwhelming numbers desperately attacked the battalion and succeeded in infiltrating through and dividing it into small units. Although completely isolated from other units and faced with possible annihilation, the members of the 3rd Battalion fought furiously to hold their positions and by mid-morning had completely beaten the hostile forces, who suffered tremendous losses in personnel and equipment.

“During this action, the 3rd Battalion captured more than 600 prisoners, including the Commanding General of the German 198th Infantry Division.”

Blocking of the main Germans escape routes through the Rhone was intermittent and mainly accomplished by artillery. Although effective, the U.S. artillery was short of ammunition, and unable to do as much damage as possible on the steady stream of German targets. The 3rd Division was hampered by supply and transportation shortages in getting to the combat area. Units of the 36th Division could not move as fast as hoped in the “battle square” itself.

Truscott, however, was able to travel. He arrived at Dahlquist’s headquarters on the morning of August 26, intending to remove Dahlquist. Truscott complained that Dahlquist had failed to carry out instructions to block the highway and was sending in faulty situation reports. Truscott wrote that he told Dahlquist, “John, I have come here with the full intention of relieving you from your command. You have reported to me that you held the high ground north of Montelimar and that you had blocked Highway 7. You have not done so. You have failed to carry out my orders. You have just five minutes in which to convince me that you are not at fault.”

Dahlquist blamed much of this on the confusion of battle, including one case in which the wrong hill was taken. German attacks in the northeast corner of the square, at Crest and Puy, made the defense of these towns necessary. Supply and transportation shortages made it impossible to concentrate sufficient combat power on Hill 300 or to establish a permanent physical block across Highway N-7. Truscott saw the terrain difficulties but ordered further attacks the next day. Though Truscott remained unhappy, Dahlquist kept his job.

The author of the 141st’s regimental history later wrote, “In the fighting around Montelimar, operations were often in a confused state. Near Crest a fleeing Jerry motorcyclist approached a crossroads near the Division Command Post. Standing there was one of the faithful Division MP’s attempting to keep straight the mobile affairs of the 36th. Seeing the Jerry speeding toward him in frantic flight, the MP, following the dictates of his habits, helpfully waived him on.”

Tactical operations remained basically stalemated through the next few days. Neither side did as well as it might have done. Both failed to capitalize on opportunities. Supply problems made it impossible for the Americans to close the road and trap the Germans troops. Most made it out, but they took heavy materiel damage and high casualties. Germans units passed into the Vosges far weaker than they might have done otherwise.

The 36th Division was primarily responsible for this damage, though Dahlquist probably was not as aggressive as he could have been. In a letter written mid-battle, Dahlquist blamed himself for letting the Germans escape. Truscott would agree. However, Dahlquist was new to command of a combat division and had never before worked with Truscott. He probably could have used closer guidance in his first major engagement. He definitely could have used more supplies, transportation, gasoline, and ammunition. The rapid advance inland of the VI Corps, and the fact the Marseille and Toulon were not captured until the end of the battle and made usable as ports until sometime later made this unlikely.

There was room for improvement, but objectively the 36th Division passed its first real test in France. “Our operations in Southern France were completed,” a division historian summed up. “Ahead of us, behind misty grey curtains of rain and fog, rose the formidable Vosges Mountains, which no army had ever before managed to penetrate in force.”

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments