By Glenn Barnett

Gene Verge was born in Pasadena, California, in 1918. As a young man in 1941 he faced the probability of being drafted. He had already completed two years as a student at nearby Glendale Junior College and could be drafted at any time. He decided that he preferred the Navy to the Army and learned of a 90-day “wonder” program in Chicago that would graduate him as an officer.

Before he left for Chicago, a neighbor who had spent his career in the Merchant Marine taught the young man how to navigate by sextant, read nautical maps and charts, and use a compass. This knowledge impressed his teachers in Chicago, and upon completion of the 90-day course he was commissioned an ensign in the United States Navy. He was asked if he preferred to serve in the Atlantic or Pacific. He chose the Pacific, as it was closer to his Southern California home.

From Chicago, Verge went by train to Long Beach, California, where he was lodged in the officer’s quarters until he could ship out to Hawaii. As a newly minted officer, Verge arrived at Pearl Harbor in August as a passenger aboard a hospital ship and was immediately assigned to the seaplane tender USS Curtiss as an assistant navigation officer. With this assignment he would be stationed on the bridge.

“Bombing Practice on Sunday Morning?”

The Curtiss was part of a task force commanded by Vice Admiral William Halsey, whose flagship was the aircraft carrier Enterprise. The task force sailed for Wake Island to deliver food and supplies to the Marine outpost. Besides the Enterprise and Curtiss, remembers Verge, the convoy included four destroyers and four cruisers. Halsey ordered the ships to be on full wartime alert because of the very real threat that the Japanese might attack at any time. All the shipboard guns were manned, and lookouts kept sharp eyes out for unknown vessels and aircraft.

Having completed this mission, the Curtiss arrived safely back at Pearl Harbor just after noon on Saturday, December 6, 1941. The live ammunition at the ready during the cruise was safely locked in magazines. Around 5 pm, the captain and two thirds of the crew went ashore for the remainder of the weekend. Only a skeleton crew remained aboard on Sunday morning when the Japanese did attack.

Verge, having little seniority, was left on board. At 4 am, the young ensign arrived on the bridge to stand watch as officer of the deck for the next four hours. All was quiet. He was relieved just before 8 am and, eager for sleep, decided to sack out and skip the breakfast of coffee, toast, eggs, and bacon being served in the mess that morning. He told his replacement, “I’m going to sleep. It’s Sunday morning.”

Verge walked back to his berth, unbuttoning his uniform on the way. Just before reaching his cabin, he heard three explosions on nearby Ford Island. His immediate thoughts were the same as every serviceman in the Honolulu area: “Bombing practice on a Sunday morning? Someone is going to be in trouble.”

He went out on the galley deck to see what was going on. As he looked over at Ford Island, he saw fires burning in two hangars. He also saw the offending planes make a slow banking turn. He could see the red circles on the wings and knew at once what they meant. He ran to his room and called the bridge. “Did you see that?” he asked the officer of the watch. “Yes, what should we do?” he was asked. “I think you better sound the general alarm,” Verge replied.

Verge put down the phone and raced to the bridge while rebuttoning his uniform. Meanwhile, the ship’s alarm wailed its call to action and the announcement was made, “Battle stations, this is no drill!” The sound was repeated throughout the harbor. The other officers still aboard had duties in other parts of the ship, so the 22-year-old ensign found himself the ranking officer on the bridge of an undermanned ship under attack. The sky seemed to be full of enemy planes.

The Importance of Sea Planes

The Curtiss was a prime target that morning. Maps later found in the wreckage of Japanese planes showed where each ship was in the harbor. The battleships were marked with Xs meaning they were priority targets. The Curtiss too had an X to indicate its importance. Although the aircraft carriers were not in port that day, a seaplane tender was the next best thing. In 1941, seaplanes performed vital functions for the world’s navies, including reconnaissance, rescue, and sometimes combat operations.

The flying boat had dominated international airline service in the 1920s and 1930s. The Pan Am Clippers were the only planes that could fly from the West Coast of the United States all the way to Hong Kong and, by implication, Japan. They could land in any sheltered harbor at primitive islands where no airports existed.

The Consolidated PBY Catalina flying boat was purpose built for the Navy as a patrol bomber. On its maiden flight in 1936, it completed a nonstop flight of 3,443 miles. Future flights improved the Catalina’s range.

The Curtiss was a new ship, launched in 1940 and named after Glenn Curtiss, inventor of the seaplane and father of naval aviation. When the ship was launched it was christened by his widow. The Curtiss was a big ship for the time, displacing 8,671 tons, reaching 527 feet in length, and housing a crew of nearly 1,200 officers and men. Amenities included a soda fountain, movie theater, and library. The Curtiss was armed with four single-mount five-inch guns and four quad 40mm gun mounts for defense against enemy aircraft.

The Curtiss was designed to care for the Catalinas. She carried them in her hangar, fueled and armed them, launched and retrieved them, repaired and supplied them, housed and fed their pilots and crew, and served all the functions that an aircraft carrier would for Navy seaplanes.

Fighting the First Wave at Pearl Harbor

With their ship under attack, the diminished crew of the Curtiss rushed to her guns, but the ammunition was stored in the magazines, and these were locked with no keys to be had because the men entrusted with opening the locks were ashore. The magazines had to be broken open. Once the ammunition was brought up, the guns of the Curtiss swung into action, firing their initial shot within 15 minutes of the first bomb blast. The guns remained in action throughout the battle despite the absence of most of the crew. The few men who remained aboard accounted for at least one and perhaps two enemy planes. One gunner later noted that there were only three men available from his gun crew of seven sailors.

Meanwhile, the engineers in the boiler room below were ordered to work up steam for an emergency move if necessary. Number 3 boiler was already in use as it was needed to power the ship’s electrical system in port, and two more boilers were soon kindled and made ready for emergency action.

The first wave of the attack concentrated on the battleships and airfields. The second wave looked for other targets, especially the Curtiss. A Japanese torpedo plane in the first wave, flying just above the water, released its weapon toward another ship but was shot at by any number of guns then firing. Smoke poured from its engines, and it stayed level long enough to smash into a crane on the stern of the Curtiss, starting fires in the hangar. The pilot, who could not escape, may have decided to deliberately crash into the American ship. In 1945, the Curtiss would be hit by a Japanese Kamikaze at Okinawa.

Verge rushed from the bridge to help shorthanded fire control parties and assist the wounded. He attended one man with severe burns but could not save him. As the crewmen extinguished the flames of the crashed Japanese plane, they pulled the dead pilot from the wreck and pushed the plane over the side. Verge looked at the dead Japanese pilot and noticed that he was wearing what looked like American-style swim trunks, but not just any trunks. They were the kind sold in a popular local Honolulu department store called McInerny’s. Verge remembers thinking, “He’s been here before.”

Taking in Water

More Japanese planes turned their attention to the Curtiss. There were several near misses from dive bombers and a hit that did minor damage to the superstructure. One dive bomber made a successful drop on the ship with a 500-pound bomb that pierced the boat deck and three lower decks, bouncing off a roll of cable before exploding in the magazine of the No. 4 five-inch gun.

Eighteen men were killed instantly, and some were incinerated beyond recognition. The explosion caused fires in the hangar and on the main deck aft. The No. 4 gun was put out of action. Fortunately, the 300,000-gallon capacity fuel tanks, now empty after the cruise to Wake Island, were not punctured.

However, the resulting blast in the magazine punched a hole in the side of the ship at the water line on the port side. Seawater began to pour in. This news was rushed to the bridge, where Ensign Verge ordered counterflooding. The resulting list to starboard had the effect of raising the port side hole above the waterline, which prevented further flooding.

Sinking a Midget Submarine

At least three other near misses were observed by the ship’s gunners as they kept firing at incoming Japanese planes. Crewmen then noticed a periscope and conning tower in the water a short distance away. An alert sailor on the bridge knew that the large American submarines of that day could not sail submerged in the shallow waters of Pearl Harbor. The submarine must be Japanese. In fact, it was one of several two-man midget subs that had attempted to enter Pearl Harbor that morning. Either the sub was having technical difficulties or had to surface to visually acquire a target. The surface of the water by that time was covered with oil and other debris that may have obscured the view from its periscope.

Verge ordered his gunners to fire on the sub. Five-inch shells made their way in the sub’s direction, but by now it was so close (perhaps 50 yards) to the Curtiss that the gunners could not depress their guns enough to hit it. The submarine reportedly fired a torpedo at the Curtiss. The torpedo supposedly missed, running aground in a channel at Pearl City.

As the submarine turned parallel with the Curtiss and moved farther away, a gunner managed to put a five-inch shell through the conning tower. At the same time, Ensign Verge ordered his signalmen to alert a passing destroyer, the Monaghan, to the danger. The destroyer rammed the two-man submarine from behind, shearing off its propellers and crushing the aft section of the hull. Then she dropped two depth charges on the sub, which exploded 50 to 100 years behind the destroyer. The sub lurched forward about 50 feet and then sank.

As the second wave of Japanese planes departed, more ammunition was made ready, damage assessed, and the dead and wounded attended to. Twenty-one men of the Curtiss died that morning, and some 60 others were wounded. The exhausted men remained at their battle stations until 6 pm, when the captain and the rest of the crew finally trickled back aboard when they were able to hitch rides on small boats. The long day was over.

Seven Battle Stars in the Pacific Theater

The next morning, the captain asked Ensign Verge to lead a party to recover the sunken submarine. Verge picked a small party and used a ship’s boat to drag the bottom with grappling hooks. When the sunken vessel was found, divers attached chains to it and a nearby tractor was enlisted to pull the sub to the beach at Pearl City. There was a hole in the conning tower where a shell had passed through. The hull was crunched where the Monaghan had rammed it and from the detonations of the depth charges. Both crewmen were dead.

Reports had spread that this submarine had launched a torpedo at the Curtiss and that it missed, but Verge disagrees. As the officer in charge of bringing the sub ashore, he observed that both of the sub’s torpedoes were still aboard and neither had been fired. It is true that different people remember the battle in different ways, but Verge’s physical observation indicated that the midget sub had not launched any torpedoes that day.

The Curtiss continued to lie at anchor for some weeks before space could be made in a dry dock to repair the damage to her hull. Other ships had priority for repair, but eventually her damage was patched up and she again stood out to sea.

Ensign Verge stayed with the Curtiss for a short time as part of the crew that secretly delivered supplies to Midway Atoll in advance of the battle there. Then the two parted company. The Curtiss went on to earn seven battle stars during the Pacific War. She would later serve in the Korean War. Her career ended during the testing of nuclear bombs at Bikini Atoll.

Gene Verge on the USS Wabash

Gene Verge transferred to Seattle, Washington, where he was promoted to the rank of lieutenant (j.g.) and assigned as executive officer of the Patapsco-class gasoline tanker USS Wabash. He sailed aboard Wabash five times to deliver gasoline to Alaskan ports. In October 1943, the Wabash was sent to Hawaii to support operations in the western Pacific. Verge eventually rose to command the ship.

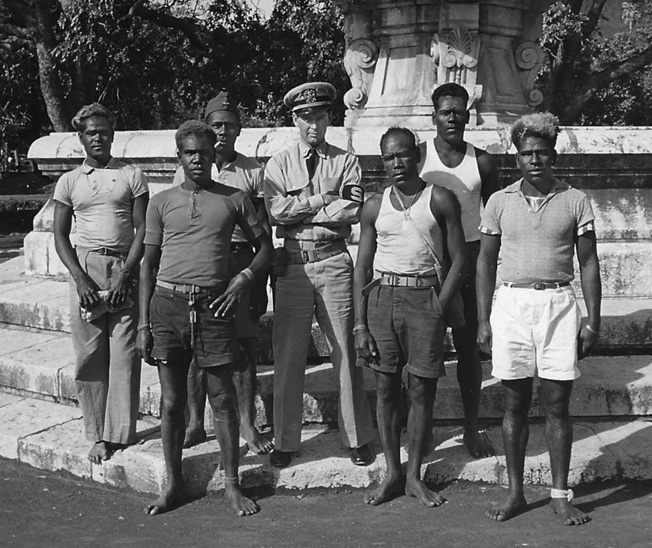

About that time a convoy of tankers was being assembled at Pearl Harbor to carry aviation fuel and lubricants to outposts in the western Pacific. Admiral Chester Nimitz, commander in chief of the Pacific Fleet, personally picked Verge to command the convoy and ordered the young officer to meet with him in his office to discuss it.

Nimitz had no idea how young Verge was and asked bluntly, “How old are you, son?” “Twenty-three, sir,” he replied while standing stiffly at attention. It was a white lie. He would not be 23 for another month.

Nimitz was shocked. “I’ve got five ships sitting outside the harbor, and the skippers of all those ships have been to sea for 20 years or more.” Nimitz mused. Then he ordered, “You’re going to take that fleet to Saipan tomorrow but don’t ever let them see you.”

Verge commanded the Wabash for the next three years. Late in the war, he was ordered to take a load of aviation fuel to Tinian, an island in the Marianas chain. Fuel was pumped from the ship to tanks ashore to support the bombing campaign against the Japanese homeland. At war’s end, Verge visited Japan as part of the occupation force and saw the horrific results of that bombing.

Returning After the War

After the war, Verge was sent back home and assigned to a training facility on the East Coast. He was promoted to the rank of lieutenant commander and placed in command of the facility. He was then asked to remain in the Navy for four or five years to get the facility up and running.

Verge was used to duty aboard ship and did not take well to the land assignment. He decided to return to California to continue his studies at the University of Southern California. Today, more than 90 years of age, he still vividly remembers the Sunday morning aboard the Curtiss that will never be forgotten.

Uncle Gene never really told this story to us. I knew he had been at Pearl Harbor, and been Captain of a fast oiler during the war. He mentioned the air craft carriers leaving Pearl Harbor before the attack on December 7. He was very friendly and became an architect in Los Angeles like his father. Interestingly when his ship took gasoline to the islands of Tinian my father Norris B Smith (uncle Gene’s brother in law) was stationed there with the 20th Air Force. Of course neither knew of the where abouts of the other at that time. I always thought it interesting that in one family my uncle saw the U.S. war begin at Pearl Harbor and my father saw the war come to an end with the departure of the atomic bomb laden B 29 to bomb Japan from Tinian Island! Nephew of Uncle Gene, Stephen Bradley Smith