By Eric Niderost

On December 5, 1757, Prussian King Frederick II crushed the Austrian Army at Leuthen, Silesia, a masterpiece of military skill and maneuver that established Fredrick’s reputation as one of the great commanders of the 18th century. The Austrians lost 21,000 men, including 12,000 prisoners, many standards, and 131 guns. His momentum growing, Frederick followed up the victory at Leuthen by sweeping the Austrians entirely out of Silesia. A number of key fortress towns were put under siege and their Austrian garrisons compelled to surrender. The capture of Schweidnitz in the spring of 1758 completed the cycle of Austrian woes.

The heavy snows and bitter cold of the central European winter effectively ended the campaigning season until spring. Prince Charles of Lorraine, the main Austrian commander, had tried his best, but had proven to be no match for Frederick’s tactical genius. In September the Austrian army had numbered 90,000 men; by December, scarcely 25,000 cold, ragged, and thoroughly demoralized survivors remained. “I venture to assure you,” Frederick wrote to his sister Wilhelmine, “that this battle [Leuthen] will procure the peace.”

His assessment proved overly optimistic. Empress Maria Theresa of Austria was deeply distressed when she heard about her army’s rout at Leuthen, reportedly crying for two full days. But the empress was a courageous woman who nursed an implacable hatred of the Prussian monarch. She had never forgiven Frederick for seizing Silesia 17 years earlier, during the War of the Austrian Succession. After the initial shock of defeat was over, Maria Theresa was more determined than ever to crush her implacable foe. She summarily dismissed Prince Charles and appointed Count Leopold von Daun as the new Austrian commander-in-chief. The shattered army was gradually built up again, partly with new recruits and partly through a prisoner-of-war exchange with the Prussians. Frederick also mustered new recruits and prepared for yet another campaign if his hopes for a negotiated peace with Austria proved illusory.

Shining success though it was, the Silesian campaign was merely the latest step in a blazing war that was far from over. In the spring of 1756, Austria, Russia, France, Sweden, and a host of smaller Germanic states had formed a self-protective alliance against Frederick’s Prussia. In short order, Frederick found himself beset on all sides by a multiplying host of enemies bent on the total destruction of the Prussian state. Great Britain, Fredrick’s only major ally, stood ready to given him huge cash subsidies and, to a lesser extent, military support. But Britain was not a continental land power, and Frederick felt the need to launch a preemptive strike against Saxony in the summer of 1756. These opening moves began the Seven Years War, which would prove to be the most bloody and destructive war of the 18th century.

Frederick’s situation was somewhat eased by the successes of his brothers, Prince Ferdinand of Brunswick and Prince Henry of Prussia, who commanded troops fighting in central and western Germany. The pair managed to checkmate the French, which relieved Frederick of a major headache. But when it became clear that Maria Theresa was not going to sue for peace, Frederick once again turned his thoughts to a new campaign. Although he was preoccupied with Austria, a new menace was looming to the east. The Russian army, ponderous but powerful, was finally on the move.

Russian Czarina Elizabeth Petrovna hated Frederick and feared the growing power of Prussia. Much of the loathing was on a personal level. The czarina was a handsome, blonde-haired woman who had been beautiful when she was young. Over the years a steady succession of lovers had paraded though the imperial bedroom. Frederick took note of this and called Maria Theresa, Elizabeth Petrovna, and Louis XV’s mistress Madame de Pompadour the “first three whores of Europe.” The czarina was not going to forgive, and certainly was not going to forget, that stinging slur. After lengthy consultations with her allies, particularly Maria Theresa, Elizabeth decided to target the very heart of Prussia. She would make Frederick pay for his words.

As a preliminary step, a new commander was placed at the head of the main Russian army. General of Cavalry Villim Villimovitch Fermor was a competent officer who in the past had pushed through several much-needed military reforms. But Fermor tended to be slow and indecisive at times, and like most Russian officers, he was addicted to luxury. Nevertheless, when the Russians invaded east Prussia in January 1758, Fermor showed remarkable skill and energy. The isolated Prussian province fell with no resistance. By January 22, the Russians had entered Konigsburg, the east Prussian capital, an event that significantly boosted allied morale. The next step was to advance through Poland to the Oder River. Once there, Fermor could attack Silesia or thrust deep into the Prussian heartland at Brandenburg.

To Frederick, the conquest of east Prussia was nothing more than a minor setback, a petty irritation that was not going to divert him from his main goal. The Prussian king had utter contempt for the Russians, whom he considered ill-disciplined “rabble.” They would be swept aside in due course. The grandly named Lt. Gen. Christoph Burggraf und Graf zu Dohna, 65 years old, would be in charge of Prussia’s defense in Frederick’s absence. Frederick sent Dohna a series of letters that outlined the situation as he saw it. Sweden was another partner in the allied coalition, and there was a possibility the Swedes might try to act in concert with the Russians. This was to be avoided at all costs. Sweden must be watched and persuaded—or forced—out of the war. As for the Russians, Dohna was to confront and beat them in short order. It all seemed simple enough on paper.

The Prussian king felt that Dohna could easily defeat the Russians by himself, and in the meantime, Frederick had other things on his mind. He decided to invade Moravia and take the fortress town of Olmutz. The new Austrian commander, von Daun, was in neighboring Bohemia, where the next Prussian blow was expected. By marching on Olmutz, Frederick hoped to lure von Daun into giving battle on ground of Frederick’s own choosing. If the Austrians refused to rise to the bait, it would not be a problem. In fact, the whole scheme was a win-win situation for the wily Prussian leader. If von Daun failed to arrive, Olmutz would fall and the path to the Austrian heartland would be open. Frederick could march on Vienna, threatening Maria Theresa’s vulnerable capital. And if Vienna were taken, Maria Theresa would suffer a terrible loss of prestige. In fact, there was a real possibility that the whole allied coalition would collapse like a house of cards.

Shocked and Shamed by the King’s Courage, the Pandour Slowly Lowered His Weapon.

It was a brilliant plan, at least on paper, and when spring came Frederick lost no time in implementing it. The main Prussian army advanced on Olmutz, catching the Austrians by complete surprise. Frederick himself arrived at the walls of Olmutz on May 5, 1758. He immediately ran into trouble. The Austrians had built up the defenses over the years, much to Frederick’s chagrin. The walls were strong, bristling with 324 cannon, and Olmutz’s garrison was well supplied with food and ammunition. To make matters worse, the Prussian siege train was late, and Frederick’s engineers proved barely competent. The formal siege did not begin until May 31.

At first Frederick kept his composure. He remained as active as usual, working harder than most of his general officers, patrolling, inspecting, and reconnoitering. The king even found time to play the flute and read a French play, although he confessed that “after each act I read, [I must have] a pinch of snuff.” Soon, however, things began to sour. Prussian communications were disrupted by swarms of Austrian irregular troops, particularly the Pandours, who usually patrolled the frontier regions of the empire. The Pandours were hard-riding men from Croatia who excelled in ambush and hit-and run tactics. They also were wild and ill-disciplined, much given to rapine and pillage whenever the opportunity presented itself. Unsurprisingly, Frederick loathed the Pandours, calling them “bands of brigands.”

One of those brigands almost changed the course of European history by killing Frederick himself. The king was out riding with a small staff when he spied a Pandour hiding behind a tree. The irregular was armed with a musket and obviously attempting to ambush any Prussians that might come along the road. He leveled his musket at Frederick, the muzzle only a few feet from the Prussian king. Frederick looked at his assailant directly, his eyes blazing. “I hope you have no powder in the pan,” he blustered. The Pandour might not have understood the language, but he realized he had been spotted—and by the Prussian king himself. Shocked and shamed by the king’s courage, the Pandour slowly lowered his weapon. Frederick rode on unharmed.

The siege was not going well, and Frederick’s impatience mounted by the day. It was discovered that Prussian engineers had miscalculated the placing of the first siege parallel. In consequence, Prussian cannon were too far away, and only two shots out of 100 even reached the fortress. The mistake was corrected, but at the cost of much lost time. Equally bad, the Austrian irregulars were leaving Frederick tactically blind. Von Daun could show up at any moment. Frederick’s impatience had gastric roots. He was plagued by indigestion, brought on by bolting “too much macaroni,” and hemorrhoids made horseback riding a torture. Frederick arranged for a 4,000-wagon convoy to be assembled in Silesia to relieve his growing supply problems. The huge caravan also included nearly 1,000 ammunition wagons. This additional component was vital—after a month of pounding, Olmutz was finally beginning to show signs of weakening.

At Altliebe, a mere 20 miles from Olmutz, the Prussian convoy was ambushed by Austrian forces. The result was a disaster for Frederick’s plans. Over 3,000 wagons were captured, their precious contents seized. Whatever the Austrians couldn’t carry off was ruthlessly burned. Only about 100 wagons managed to escape and reach Frederick’s army at Olmutz. The approximately 8,000-man Prussian escort, largely new recruits, had been badly mauled. Many survivors simply took to their heels. The king took the news with his customary stoic calm. Having received reports that Dohna was being hard-pressed by Fermor, Frederick considered that perhaps it was time to alter his plans. He had come within an ace of success at Olmutz, but Frederick wasn’t one to dwell on what might have been. The loss of the convoy helped him decide. The Prussians would lift the siege and march north to face the Russians. Olmutz was abandoned on July 2.

The king left Margrave Carl of Brandenberg-Schwedt in charge of Prussian troops in Silesia while he marched north with 14 infantry battalions and 38 cavalry squadrons, somewhere around 15,000 men. Dohna was sitting tight at Frankfurt an der Oder, doing virtually nothing even though it was plain Frederick intended to take on the Russians. While Frederick was besieging Olmutz, the Russian offensive had stalled. After their successful conquest of east Prussia, the Russians had simply run out of steam. The Russians had to use Polish roads, muddy quagmires in the spring and dust-choked, rutted tracks in summer. The rivers in Poland and central Germany, running along east-west lines, formed natural defensive barriers that impeded Russian progress. The Oder River was particularly formidable, with fortified cities all along its length, from Stettin in the north to Custrin, Glogau, and Breslau in the south.

Fermor reached Custrin and began to bombard the fortress town in the early morning hours of August 16. Russian shells started several fires, which joined together to make a raging conflagration. Long trailing fingers of flame shot high into the air, producing dark, acrid clouds of smoke that could be seen for miles around. Custrin rapidly became a blackened, rubble-choked ruin, although the city still held out against beseiging Russian forces. Would the charred ruins of Custrin also be the funeral pyre of Frederick’s plans? The Prussian king knew that time was running out. The Swedes might march on Pomerania, and the newly resurrected Austrian army might pounce on weakened Prussian forces in Silesia. The Russians had to be decisively dealt with so that Frederick could go back to his original objective, the destruction of the Austrian army.

Frederick’s march north was one of the most brutal of the war, with soaring August temperatures making the sandy ground a literal hell on earth. Scissoring legs kicked up clouds of sand and dust, the gritty particles caking every pore and parching throats already dry from lack of water. The king, generally a humane man, was utterly ruthless when forced by the pressure of events. Frederick issued strict orders that anyone who left the line of march would be shot without mercy. The grueling trek continued, some soldiers dying of exhaustion and the effects of heatstroke. The men’s dark blue coats were made of wool, and soon armpits, backs, and chests were stained and soaked with rings of sweat. Felt cocked hats were topped with colored pompoms, but such martial smartness offered little protection from the broiling sun. The grenadiers perhaps had the worst of it. Their miter caps, with fronts made of brass or white metal, were cumbersome and gave little protection. Worse still, they were so hard to keep on a soldier’s head that they had to be pinned in place.

Frederick reached Frankfurt an der Oder, where he could hear the rumble of Russian guns at Custrin farther downstream. The Prussian king hurried on, finally effecting a junction with Dohna at Manschnow, west of the beleaguered fortress, on August 22. The meeting gave Frederick a combined strength of some 36,000 men. The troops had covered 160 miles in eight days under a scorching summer sun. Frederick took the time to personally visit Custrin. The civilian inhabitants were much heartened by the sight of their king, who seemed genuinely touched by their plight. After promising to do all he could to rebuild their homes and lives, Frederick left Custrin with a burning hatred for the enemy. The entire Prussian army shared his sentiments, with “every man longing for action.”

The Prussian Troops “Had to Eat Their Bread on the March and Satisfy Their Thirst From Whatever Puddle They Came Across.”

Frederick had three major objectives. First, he had to establish a bridgehead on the eastern bank of the Oder River, then cross with the bulk of the Prussian army. That accomplished, Frederick would cut the Russian line of communication, isolating General Peter Aleksandrovich Rumyansev, who commanded a smaller Russian army downstream at Schwedt, and preventing him from joining Fermor. The Prussian king wanted nothing less than a second Leuthen, a victory so complete it might knock Russia out of the war. Fermor, for his part, was greatly alarmed when he heard of Frederick’s approach from Prussian prisoners and deserters. Hasty preparations were put in place to deal with the new threat. Fermor ordered Rumyansev to destroy all bridges and boats between his location and Custrin. The Oder River had once been a barrier, stalling Russian progress west. With Frederick’s arrival on the scene it became a protective “moat” that shielded the Russians from the reinforced Prussian army.

The Prussians successfully kept the Russians off balance by cannonading the Russian siege lines at Custrin and staging noisy demonstrations at Schwedt. While the Russians’ attention was focused at Custrin, a suitable crossing site was found about 20 miles downstream at Alt-Gustebiese. An assault force of grenadiers took a few boats, rowed across, and established a foothold on the eastern bank. They were spotted by some roving Cossacks, but the wild horsemen of the steppes made no attempt to intervene. Prussian engineers quickly built a pontoon bridge across the Oder, speeding up the labor by drafting local peasants. By noon of August 23, the Prussian army was crossing the Oder without opposition. At that point, the chief enemy remained the unrelenting summer heat, which seared through uniforms and bathed bodies in torrents of sweat. The troops were given little rest; a Prussian lieutenant recalled that his men “had to eat their bread on the march and satisfy their thirst from whatever puddle they came across.”

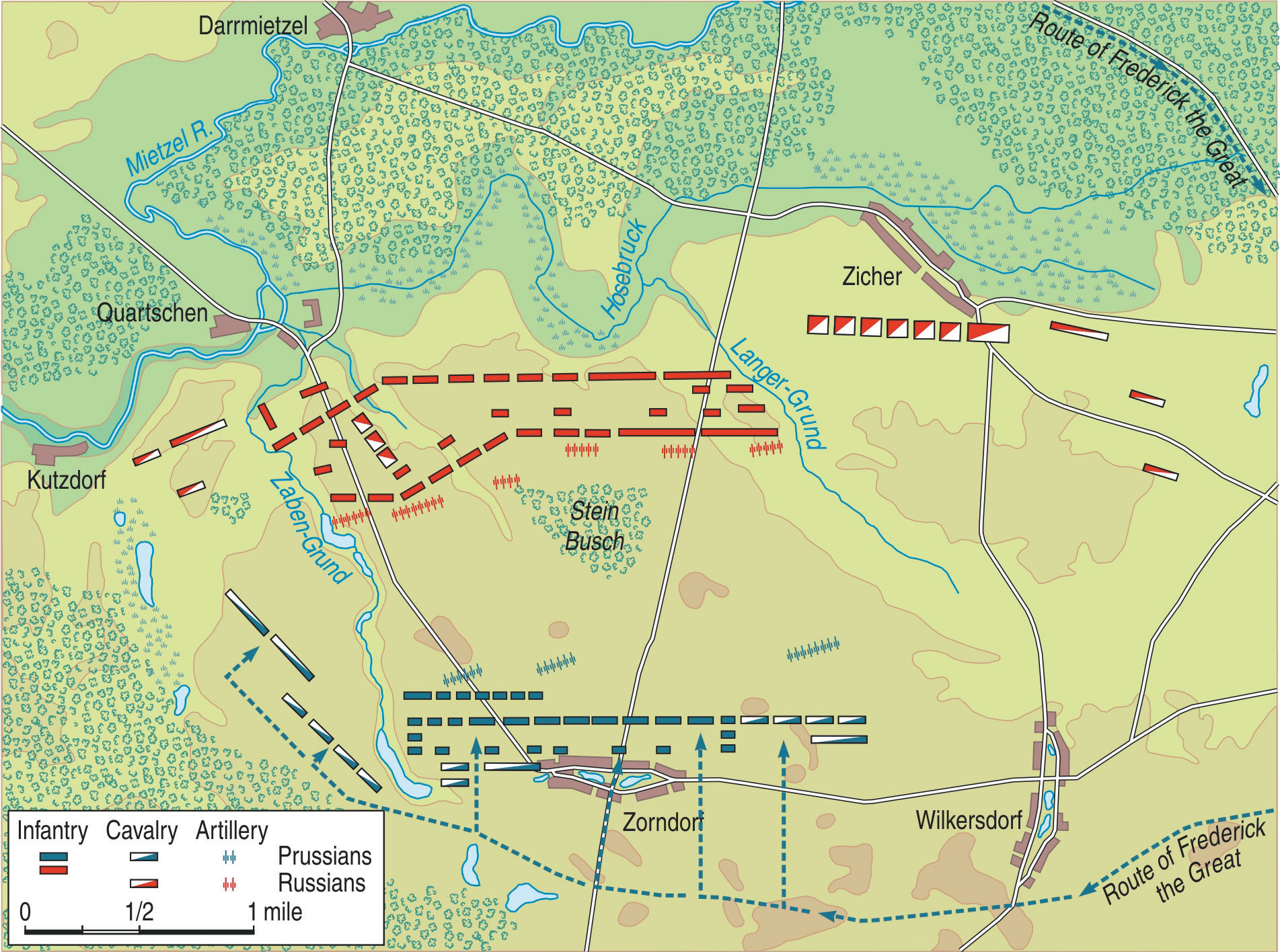

When Fermor learned that Frederick was across the Oder in force—he overestimated the enemy strength at 55,000 men—he concluded that the Prussians would attack from the south and southwest in an area around the village of Zorndorf. The Russian general raised the siege of Custrin and hurried to meet Frederick just south of the Mietzel River, a tributary of the Oder. The landscape was a patchwork of fields, rolling tree-studded hills, and three low-lying hollows that the locals called grunds. These rough grooves in the earth, which featured small creeks, hardly more than meandering trickles of water, were choked by bogs and marshes as they fitfully flowed north into the Meitzel. To the west was the Zaberngrund, whose slopes in places reached 30 feet. The Galgengrund (literally “gallows hollow”) was next, and finally the Langengrund anchored the east. The thread of water that flowed through the Langengrund was called Hosebruck, or “stocking brook,” because it was so marshy that one needed to take off his shoes and stockings to cross. A high wooded hill called the Stein Busch lay just to the north of Zorndorf and southeast of the Zeberngrund. Its fir-studded slopes were going to restrict visibility and hamper maneuvering. A broad patchwork of thick forests, mainly fir trees, hugged the Mietzel’s southern bank from Quartschen to the village of Zicher.

Fermor placed his men just north of Zorndorf, between Zaberngrund and Langengrund. The Russians were facing north, in the direction of the Meitzel River, as if Fermor expected Frederick to cross immediately to his front. The Prussian king, however, had no intention of making a direct frontal attack. Consulting with local foresters to get a better idea of the terrain, Frederick decided on a flank march around the Russian right. As a first step, the bulk of the Prussian army would cross at Neudammer Muhle (new mill dam). The cavalry would cross farther upstream at Kerstenbruck, using a bridge that was still intact. Once across, the Prussian infantry would march through Zicher woods, the thick trees and a cavalry screen successfully hiding their movements from the enemy.

The Prussians would reunite with the cavalry near the village of Batzlow, then the entire army would continue its flank march, sweeping in a wide arc until it reached the vicinity of Zorndorf village. Frederick intended to steal a march on Fermor—a great tactical victory would be gained at the cost of a little shoe leather. In the meantime, Zermor learned that Frederick was at Neudammer Muhle. The news hits him like a blow. Fermor may not have been a great general, but he wasn’t stupid. He knew what was about to occur, and realized immediately that the Russian army was facing the wrong way. The Russian commander quickly issued a flurry of orders—his army must literally execute an about-face, or else the Prussians would be attacking their rear.

The Prussian army broke camp and began its flank march at about 3 am. It was Friday, August 25, 1758, and the Battle of Zorndorf was about to begin.

In the opening hours, all went according to plan. The Prussian army crossed the river and marched rapidly through the dense woods, finally breaking cover near Batzlow about daybreak. Fermor’s position looked more and more like a trap, with the local topography representing a two-edged sword. The grunds secured the Russian flanks and prevented Frederick from fully employing his celebrated oblique-order maneuver. On the other hand, the natural dips in the ground restricted Fermor’s own maneuvering and confined his men in a relatively cramped space. Even worse, once the about-face was completed, the Russian army now had its back to the Meitzel River and the swampy banks beyond. What had been a defensive moat against Fredrick was now a barrier that blocked off any avenue of retreat. Fermor compounded his problems by ordering Cossacks to put Zorndorf to the torch. The flames produced volumes of thick, black smoke that drifted back and partly blinded the Russian right wing.

Frederick and his staff kept pace with the army’s progress, pausing occasionally to sweep the horizon with their telescopes. The king saw a wagenberg, a huge concentration of Russian supply wagons, on the horizon to the southeast. Its identity was confirmed by Prussian cavalry patrols, but Frederick was not overly worried. He had another objective in mind—namely, the destruction of the Russian army.

The Prussian forces arrived just south of Zorndorf and began to deploy for the coming offensive. All were in position by around 9 am. While his army settled in, Frederick decided on his next course of action. His intended target would be the Russian right wing, hemmed in by the Zaberngrund on one side and the Galgengrund on the other. The king realized that he could not maneuver as he did at Leuthen, but a modified oblique order might still work, delivered in the form of a frontal attack. Lt. Gen. Heinrich von Manteuffel would have the honor of spearheading the Prussian attack on the enemy right wing. His advance guard of two musketeer battalions and six grenadier battalions would need close support if the plan was going to succeed. This task would fall to Lt. Gen. Hans von Kanitz and his wing of nine musketeer battalions, four fusilier battalions, and two grenadier battalions.

“Ich bin ja, Heer, in deiner Macht”

The Russian center and left had to be neutralized if the right was going to be isolated and defeated in detail. That task was assigned to Lt. Gen. Friedrich Ludwig von Dohna, who would command the “refused wing” of 10 musketeer battalions and one grenadier battalion. About 9 am, the Prussians began their offensive with an artillery barrage on the enemy lines. The cannon opened up about 600 yards from the Russians, but at that distance the Prussian gunners were also vulnerable to return artillery fire. Guns vomited great gouts of smoke and flame, the recoil knocking them back on their trails. Gunners manhandled the pieces back to their original positions, swabbed out the hot barrels, and loaded them once again. This was hard, repetitive work, made worse by enemy fire and rising summer temperatures as the morning wore on. Soon, great dirty-white clouds of cannon smoke shrouded the field, a choking, blinding, evil-smelling “fog of war” that grew with each salvo. The Russian guns fired in counterbattery, adding to the heat, smoke, and stench. It was one of the most furious artillery duels of the war, the noise clearly audible at great distances. Civilians many miles away were startled when the ground began shaking in a continuous peal of thunder.

Just before 11 am, the guns fell silent. The heavy smoke began to clear, and before long the Zorndorf battlefield was bathed in bright sunlight. It was time for Manteuffel to begin the infantry attack. The Prussian troops moved off, long skeins of blue tramping in almost parade-ground order. Officers made sure the ranks were properly dressed, aligning the men with the long wooden hafts of their half-pikes. As the attack commenced, the fifers and musicians of one regiment began playing the German hymn “Ich bin ja, Heer, in deiner Macht” (“Now, Lord, I am in Thy Keeping”), an appropriate sentiment for men going into battle. Frederick, a notorious atheist, couldn’t help but be moved. He repeated the words with visible emotion.

A 20-gun battery was moved up to keep pace with Manteuffel’s advancing infantry, and once in their new position they did terrible execution. Cannonballs flayed, disemboweled, and amputated arms and legs with horrific ease. Russian soldiers, most of them peasants inured to brutality and able to bear horrific wounds with scarcely a murmur, stoically endured the rain of death. One Prussian cannonball killed or wounded 42 Russians in a single flight. Manteuffel’s troops emerged from the smoke, only to be confronted with a mass of Russian infantry not 40 paces away. Officers barked commands, and the Prussian ranks leveled muskets as if one man. A volley crashed out, then another and another, but the Russians absorbed the punishment and responded in kind. When cartridges ran low the Russians launched a bayonet attack. Fighting became hand-to-hand, with no quarter given or expected.

Eventually, the Russians began to give way, and a great Prussian victory seemed in the offing. All that was needed was for Kanitz to come up and support Manteuffel’s tiring soldiers. But suddenly the truth dawned—Kanitz was nowhere to be seen. What had gone wrong? Kanitz had begun the march as planned, but as time wore on he realized that his right flank was exposed. Dohna was supposed to plug the gap, but he was bearing too far east. Worried about his flank, Kanitz extended his line to the right against orders. Battalion after battalion of his command followed suit, until there was virtually no support for Manteuffel’s faltering drive. Frederick’s planned one-two punch to the Russian right flank was becoming a weak jab.

With Kanitz missing, the moment for a decisive victory began to slip through Frederick’s hands. Russian units from the Novgorod, Ryazan, Voronezh, and St. Petersburg regiments reestablished the Russian line and put new backbone into the Russian defense. As Manteuffel’s battalions took heavy casualties, his overall frontage began to inexorably shrink. Soon, a gap opened between the Zeberngrund and the 2nd Infantry Regiment, Manteuffel’s easternmost anchor. The Russians saw what was happening and cavalry moved forward to exploit the gap. The horsemen hit Manteuffel’s troops from the front, flank, and rear. Unable to stand any more punishment, the Prussians broke and ran, many of the fugitives running headlong into Kanitz’s advancing soldiers.

Kanitz was having his own troubles—Russian round shot and canister were ripping gore-splattered holes in his orderly blue ranks. A well-timed Russian bayonet charge was the proverbial straw that broke the camel’s back. Kanitz’s men joined Manteuffel’s in a headlong flight for survival. The entire Prussian left wing, at first so near to victory, was melting into an unreasoning mob.

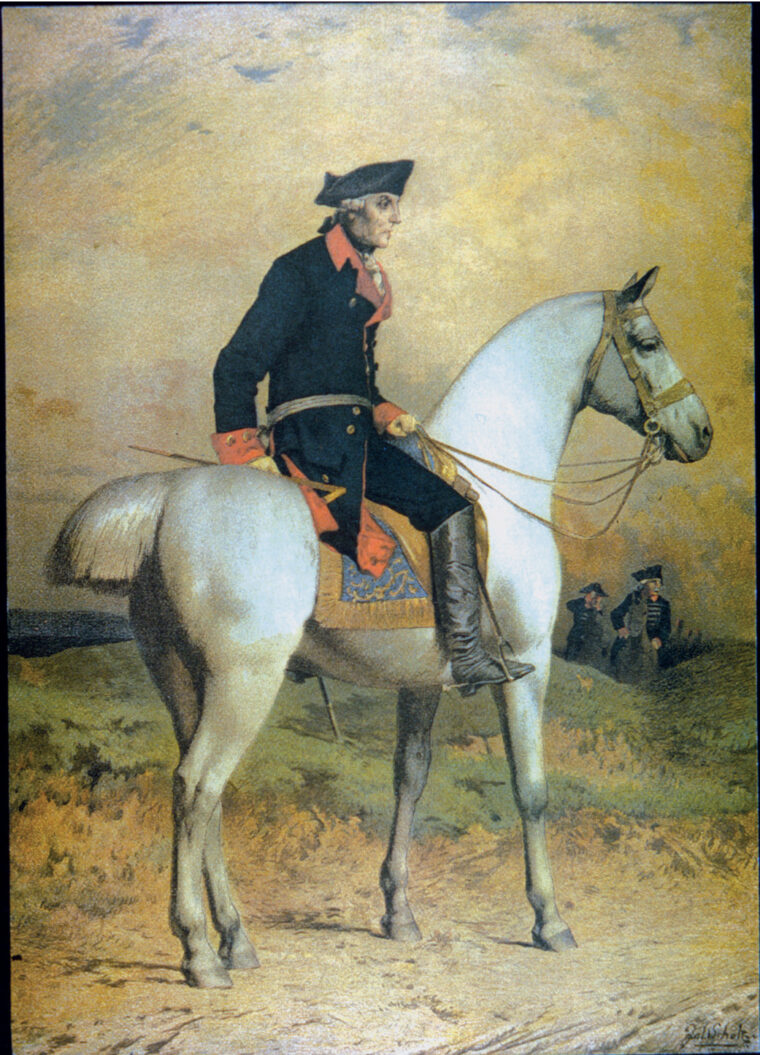

Frederick rode up and made a courageous attempt to stem the tide. Dismounting, he seized the colors of the 46th Infantry Regiment from its standard-bearer and began walking briskly toward the enemy. At this moment, legend and reality merged—here was the celebrated Frederick, affectionately known to his men as Der Alte Fritz—putting his life on the line like any common soldier. He was an iconic figure, dressed in a dark blue general’s uniform coat, a silver sash girded around his waist. His uniform was shabby and stained with snuff, the pocket bulging with an exquisitely bejeweled snuffbox. The Star of the Order of the Black Eagle was pinned to his coat, his only concession to the trappings of royalty. Although his face was weathered and seamed, the piercing blue eyes effortlessly commanded obedience.

Sword in hand, Fredrick shouldered the heavy standard and moved forward on foot, followed by his staff. One battalion of the 46th Infantry Regiment gathered near the king, but the noise and confusion of battle nullified his efforts. The retreat threatened to become a rout. There was but one chance of salvation—the cavalry under Lt. Gen. Friederich Wilhelm von Seydlitz, posted just west of the Zaberngrund. Seydlitz was a brilliant officer, and he had three cuirassier regiments, one dragoon regiment, and two hussar regiments under his immediate control. If Seydlitz could somehow get his men through the Zaberngrund’s treacherous slopes, he might be in a position to surprise the Russians and take them in flank. The king sent message after message to Seydlitz, ordering the cavalryman to move forward. He refused the royal commands, airily informing messengers, “Tell the king that after the battle my head is at his disposal, but meantime I hope he will permit me to use it in his service!”

The Prussians Suffered 13,000 Casualties While the Russians Lost 18,000 Men with Another 2,000, Including Six Generals, Taken Prisoner.

Seyditz knew that in battle timing was everything, and he judged that the time was not yet ripe for a cavalry attack. His men had already discovered that there were some parts of the Zaberngrund that horses could cross, and he carefully noted the locations. It was all a matter of when to attack. Events soon proved Seydlitz right. When he saw an opening, he moved off, the 2nd and 3rd Hussars in the north, the 8th and 10th Cuirassiers in the center, and the 13th Cuirassiers and 4th Dragoons in the south. The Zaberngrund was steep, its lowest reaches boggy, and Seydlitz’s formations were disordered by the crossing. Once they were safely over the hollow, he formed his men into regimental columns on a three-squadron front.

The Russian cavalry and infantry, pressing forward against the fleeing Prussian left wing, were caught by surprise and ruthlessly slaughtered. Other Prussian cavalry under Moritz of Anhalt Dessau, already in action before Seydlitz’s appearance, joined the formidable cavalryman and redoubled their efforts. The sabering went on for quite some time. Russian soldiers scattered in all directions, some seeking refuge in the Zaberngrund or continuing on to the Drewitzer Woods. Others came across the Russian light baggage train and began to pillage its contents. Casks of brandy were discovered, and before long many Russian soldiers were blind, staggering drunk. When officers tried to restore order, they were threatened and even shot.

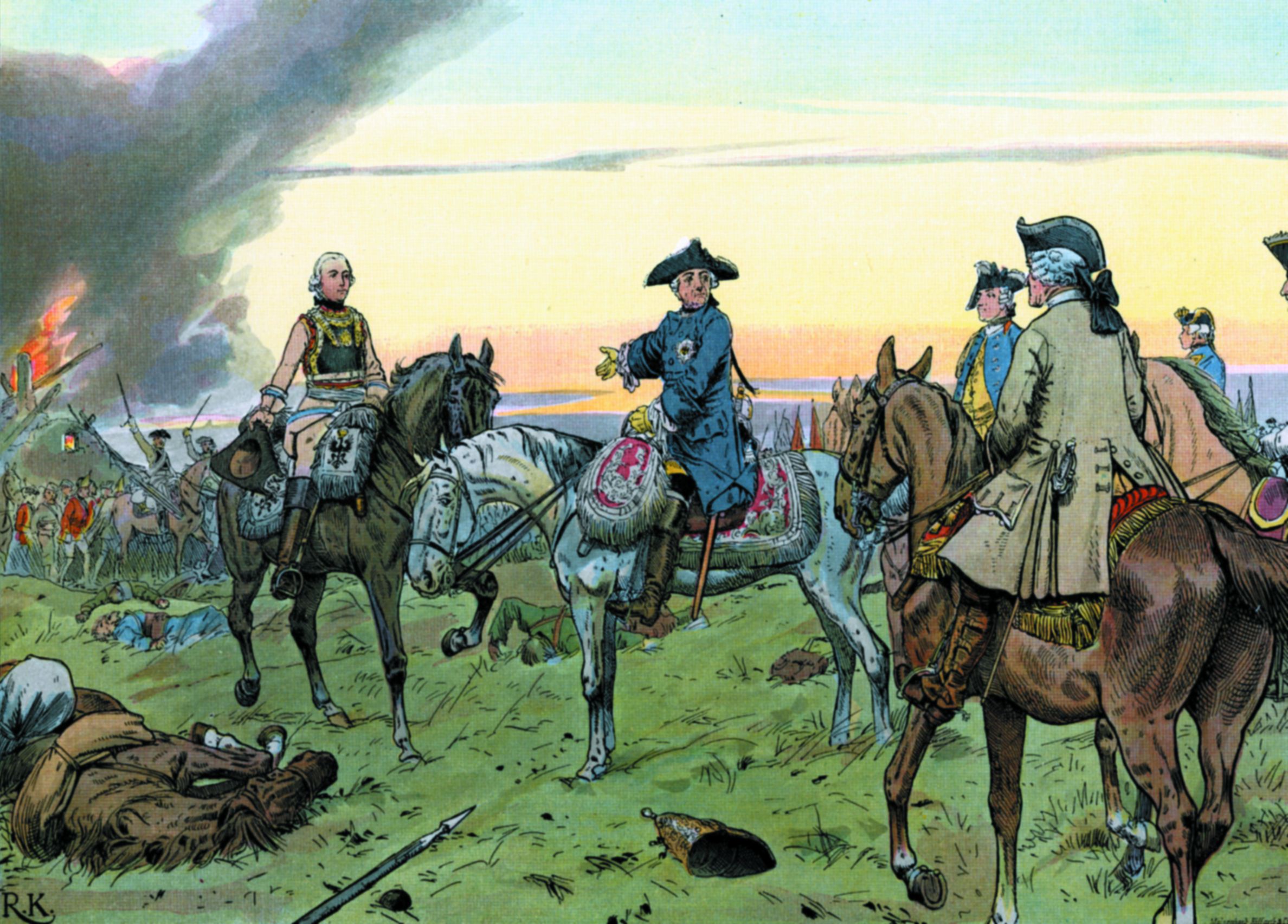

The majority of the shattered Russian right crossed the Galgengrund and joined what remained of the army. The Prussian cavalry was triumphant, but their horses were blown and the troopers spent by the sheer exhaltation of their success. The Russians were badly shaken, but so was the remnant of the Prussian left, and Frederick was far from a decisive victory. Seydlitz’s magnificent charge had saved the Prussians for a time, but the battle was not yet over. It was about noon, and a temporary lull ensued while each side licked their wounds and considered future options. In general the Russians were the worst off, having suffered terrible casualties. They were also a body without a head—throughout much of the battle, Fermor was nowhere to be seen. (He later claimed he was in Quartschen having a wound dressed, but some reportedly saw him miles from that village.) Fermor seemed to have had a loss of nerve, completely abdicating his responsibilities and abandoning his post. Deprived of leadership, the Russian soldiers had nothing left but their stoic, fatalistic courage and their ability to endure any punishment with stubborn pride.

The second half of the battle mainly consisted of heavy and ultimately fruitless attacks on the reconstituted Russian line. There were advances and retreats, attacks and counterattacks, but neither side gained much from their efforts. Zorndorf degenerated into a soldier’s battle, a bloody, toe-to-toe slugfest where the two sides bludgeoned each other with little finesse and less mercy. At 3:30 pm, Dohna’s command, some 9,000 men in all, attacked the Russian line in a last bid for victory. After the usual exchange of volleys, the fighting again became hand-to-hand, with bayonets, clubbed muskets, swords, and pikes doing deadly service. The dead and wounded covered the ground like a blood-spattered carpet of blue and gray.

In truth, the Prussians had never encountered such an enemy. The Russian soldier was incredibly tough, able to absorb terrible punishment and still keep fighting. By 6 pm, however, the battle was over. The Russians had been horribly decimated but not broken. British envoy Andrew Mitchell wrote movingly of the “horror and bloodshed,” noting that “the country was all in flames around us.” Mitchell felt that without Frederick’s coolness and courage, the Prussians would have been destroyed. “His firmness of mind saved all,” Mitchell insisted. “The Russians fought like devils incarnate.”

Frederick had won a somewhat pyrrhic victory, absorbing crippling losses he could ill afford. Worst still, Zorndorf was not the knockout blow he needed to compel the Russians to sue for peace. He had hoped for a second Leuthen, but what he got was an inconclusive massacre. Casualty figures bore mute testimony to the battle’s sheer ferocity. The Prussians lost 13,000 men, and Russian casualties were even higher—some 18,000 killed or wounded and another 2,000, including six generals, taken prisoner. But Russia had a large population and the depleted ranks were easily filled again. Frederick’s losses were not so easily replaced, especially when Prussia still faced a host of enemies.

All in all, Zorndorf had been a sobering experience. Frederick now realized that the Russian army, which he had treated with utter scorn, was a formidable enemy when properly led. It was a lesson he would not forget.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments