By Randall B. Ingram

Everyone has seen the now famous photograph of the three firefighters hoisting Old Glory over the ruins of the World Trade Center. Much has been said about its resemblance to one of the most famous photographs ever taken, the flag raising atop Mount Suribachi on Iwo Jima during World War II. That picture captured the imagination of the American people, and indeed the entire free world in 1945. It was the embodiment of the American fighting spirit, its image the very essence of heroism and determination. It has in combat. Today, he rests in a quiet cemetery, virtually forgotten outside his rural Kentucky hometown.

There were six flag raisers, although only four are visible. On the far right planting the flagpole is Harlon Block of Texas, a star football player who enlisted in the Marines along with all the seniors on his high school team. Between Harlon and Franklin is John Bradley, a Navy medic from Wisconsin who received the Navy Cross for bravery, then stuffed the medal in a closet, never telling his family of its existence. On the far left of the photo, reaching but never quite able to clutch the pole, is Ira Hayes of Arizona, a Pima Indian. His whole life would be like that, always reaching and never quite grasping. The two men on the other side are barely discernible in the photo. Rene Gagnon of New Hampshire would forever try to capitalize on his newfound fame, only to see each lucky break somehow slip through his fingers.

Finally stands Sergeant Mike Strank, whose only visible feature is his right hand helping Franklin’s to steady the pole. A Marine’s Marine, his birthday shared the same date as the Marine Corps founding. His men absolutely idolized him. Mike taught them how to kill the enemy, but would also say, “Listen to me, and I’ll get you home to your mothers.”

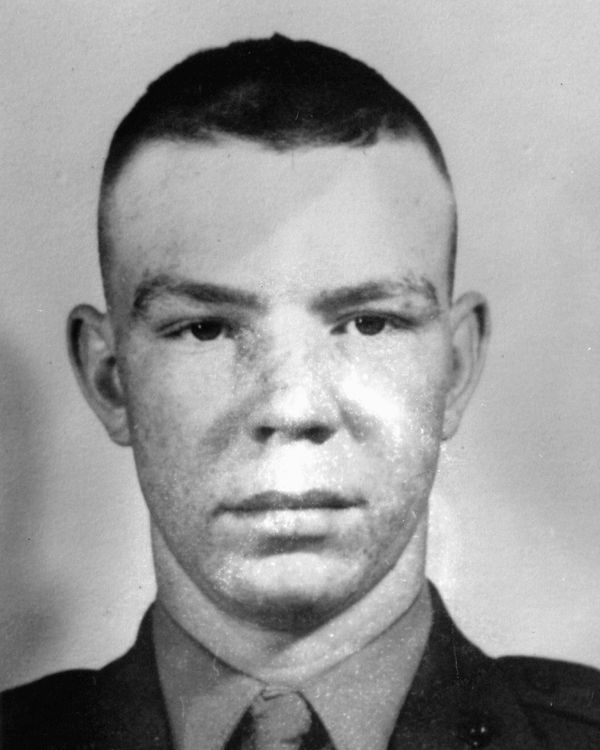

Franklin Sousley from Hilltop Kentucky

Then there is Franklin Runyon Sousley from Hilltop, Kentucky, second from the left. He was the second of three sons, born September 19, 1925. The name goes all the way back to 1809, when the first Franklin Sousley was born. The Sousleys were not wealthy, nor were most people living through the Great Depression. There was electricity, but indoor plumbing was only the stuff of dreams. Mostly, life was about work; and it was hard work, usually tobacco, but also putting up hay and milking the cows that provided milk for the family. His older brother died in his mother’s arms from appendicitis when Franklin was just three. Franklin and his mother Goldie drew particularly close as she sought to find solace in him. The bond would only grow with time.

In 1931, Franklin began his education in a two-room schoolhouse in nearby Tea Run, and continued at a larger schoolhouse in Elizaville. Three years later, his father died of diabetes. At age nine, Franklin became the man of the house, and his mother became even more emotionally dependent upon him. In school, Franklin was academically perfect—all Cs. With chores before school and work around the farm until dark, there was little time for studying or after-school athletics. It was not an easy life, but those who remember him best recall a boy with a quick and ready smile who loved to hunt and fish in the nearby Licking River. Moreover, he loved that farm, saying it was his dream to someday return there and live out his years.

Upon graduation, Franklin came north. Dayton, Ohio, was by then a bustling wartime town with plenty of opportunities for someone willing to put in a hard day’s work. He found his way to Frigidaire Plant 2 on Springboro Pike, working as a staker and assembler on the propeller line. During the week, he stayed in an apartment at 107 Park Drive in East Dayton. Weekends often found Franklin making the long trek back home to see his mother and his longtime sweetheart, Marian Hamm. Things might have stayed that way, but in December 1943 a telegram from a certain Uncle Sam changed all that—Franklin had been drafted. Instead of going into the Army, Franklin opted, like many young men his age, to join the Marines.

“When I Come Back, I’ll be a Hero”

December 7, 1941, came as a shock to America. When Japanese bombs rained down on Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, on that Sunday morning, the United States was an isolationist nation wanting no part in another European war. Franklin and his mother were down at the barn milking the family cows that evening before church when word came. He knew it meant nothing less than war. Three days later, Nazi Germany declared war on the United States. Now there was no turning back. America would have to fight two major wars at the same time.

Franklin set about proving himself during the seemingly endless weeks of boot camp at Camp Pendleton, California. While laughing off a lot of good-natured ribbing about his thick Kentucky drawl, he did admit to some feelings of loneliness in letters written to his mother. “I believe I am homesick for once in my life. If you had treated me mean before I left, it wouldn’t be so hard to forget. But you were so good that when they [the Drill Instructors] start raving around here, I think of home.”

It was a big day in the normally placid, quiet country town of Hilltop, Kentucky, when the lanky, freckle-faced Marine returned home after boot camp for a much needed rest. “He stepped off that train in his Marine dress blues looking straight as a string,” remarked a childhood friend. He seemed bigger now too. On his last night home, Franklin summoned up the courage to ask his longtime sweetheart, Marian, to wait for him. It was a risky proposition. What if she said no? He was going off to war; she had to be aware of the danger. When he finally popped the question, she thought for a moment and then gave her answer: Yes, she would wait! Franklin was overjoyed and much too excited to go home. He spent a good part of his last night home on the front porch of the Hilltop General Store reminiscing with friends about the good old days and talking about how great it was to be a Marine. But foremost in his thoughts was that girl down the road.

Sad farewells were exchanged at the train station the next morning as Franklin prepared to leave. Goldie just didn’t want to let her boy go. Following a long, tearful hug, he looked directly into his mother’s weary eyes and promised her, “Momma, I’m gonna do something to make you proud of me.” And saying goodbye to Marian before boarding the train to Maysville, his parting words were, “When I come back, I’ll be a hero.”

Iwo Jima by the Numbers

Franklin was assigned to the newly created 5th Marine Division, some 21,000 strong, whose purpose was to offset the staggering losses incurred in the war so far. Eventually, the 5th would become the most highly trained division in the history of the Marine Corps. Yet it would fight in only one battle. On September 19, 1944, the Marines set sail for Hawaii. It was Franklin’s 19th birthday and would be his last.

Advanced Infantry Training, or AIT as they like to call it, is basically boot camp after boot camp—except the bullets are real and the training more intense. Franklin found himself at Camp Tarawa, a 40,000-acre cattle ranch nestled in the rugged foothills of the island of Hawaii. Thick volcanic ash from two nearby volcanoes covered everything. The Red Cross deemed the site unsuitable for prisoners of war, but perfect for the Marine Corps. Easy Company would spend the next four months there, honing its skills at beach landings, climbing down the sides of ships into landing craft, and maneuvering under fire.

The huge armada that finally made its way from Hawaii was 70 miles long and contained 500 ships. Some 100,000 Marine and Navy personnel sailed 4,000 miles over the next three weeks before reaching their target, a tiny, desolate island 650 miles south of Tokyo Bay called Iwo Jima. Barely five miles in length and shaped somewhat like a large pork chop, Iwo Jima is dominated on its southern tip by a huge inactive volcano called Mount Suribachi. The island’s surface is quite similar to what one might find on the moon. Barren, rocky, and virtually void of vegetation, a thick sulphur ash coats everything and is several feet deep in some places along the beach.

For the Americans, Iwo Jima was a staging point for the inevitable invasion of Japan. For the Japanese, it was home soil, sacred ground that had been a part of Japan’s empire for over 4,000 years. To the Japanese, an invasion of Iwo Jima was an attack on Japan itself. They began fortifying Iwo in May 1944, when the emperor himself handpicked General Tadamichi Kuribayashi to lead the island’s defense. The general knew he could not possibly win the battle. Instead, his effort would be to kill as many Marines as possible and shock the war-weary American public into not supporting an invasion of Japan. His strategy was to let the Marines land unopposed, and once the beaches were clogged with men and equipment, destroy them.

The defense of the entire island was designed toward this goal. Over 750 blockhouses and pillboxes manned by 22,000 Japanese were neatly camouflaged into the landscape, each one strategically located to have interlocking fields of fire and support. Months were spent setting up and sighting the myriad machine gun, mortar, and artillery pieces. General Kuribayashi brought in the best fortifications specialists in the Japanese Army. Quarry experts, mining engineers, and labor battalions worked around the clock to devise a complex system of underground tunnels and caves 16 miles in length and five stories deep. There were 1,500 underground rooms, electricity and ventilation, even a hospital. He could shuttle entire units of men from one end of the island to the other in minutes.

Hitting the Beach

Over 70,000 Marines were massed in their landing craft on February 19, 1945, hurtling toward their destiny in wave after wave along a two-mile beachhead. Seventy-two straight days of naval and aerial bombardment, the longest of the war, had just concluded; 5,800 tons of bombs had been dropped on Iwo’s surface. Enormous 2,600-pound shells from the 16-inch guns of U.S. Navy battleships sailed overhead. At 9:05, the first landing craft hit the beach, taking only light small arms fire. Men and machines were instantly bogged down in the soft, sucking, volcanic sand. The Japanese held their fire. More men and equipment were hitting the beach now; units were starting to form up. Still, they waited.

Easy Company landed with the 12th wave near the base of Mount Suribachi at 9:55. There were now 6,200 Marines strung out along a 3,000-yard beachhead. Suddenly, the entire island exploded. Bullets, mortars, and artillery shells fell in torrents from hundreds of concealed positions, shredding the ranks of the stunned Marines. The landing zone was instantly transformed into a maelstrom of death. There was simply nowhere to hide. Digging a foxhole was almost impossible. As soon as each shovelful was scooped out, the hole filled up again. Still the assault waves kept coming. One Amtrac took a direct hit, instantly disintegrating everyone onboard. The noise from all those guns and the constant explosions rose to a point where the din became one loud, deafening roar. Franklin and the men of Easy Company were caught on the terraces just beyond their landing zone.

Franklin and the other survivors of Easy Company worked their way up over the terraces and were moving inland, albeit at a snail’s pace. They were a part of the 28th Regiment, whose task was to cut across the island at the base of Mount Suribachi, isolating it from the rest of the island. Suribachi and its 2,000 Japanese defenders had to be taken if the Marines were to have any hope of winning. They crept, crawled, and staggered forward, sometimes sprinting forth like athletes at a track meet. Now all the months of training began to pay off. Many were cut down in the process, but usually Marines were able to destroy the defensive positions with grenades or satchel charges. Then they would move on to the next one, yard after bloody yard throughout the entire day.

The rains, which had been mercifully absent on day one, pounded Iwo Jima with a fury as the curtain lifted on the second day. Easy Company had it pretty good for a while, being held in reserve in case of counterattack. There were now 33,000 Marines on the island, and the 28th Regiment, some 3,000 strong, was attacking Mount Suribachi. Ordered up to the front lines around 4 pm, Easy quickly came under heavy enemy fire. At one point, Franklin, Mike, Harlon, and Ira helped rescue five gravely wounded friends by dragging them into a trench. A tank was then directed over the ditch and the crew loaded the wounded up through its bottom hatch. By the end of the day, with all their suffering and loss of life, the Marines had gained 200 yards.

“If You Get to the Top, Put it Up”

By February 23, the rainy weather finally let up. The day loomed large for the 28th Regiment. At 9:30 am, a couple of four-man patrols were ordered to the top of Mount Suribachi. Surprisingly, both returned about an hour later unscathed, one having made it all the way up to the top of the volcano. Still, everyone was suspicious; it had to be a trap. The decision was made to risk sending a platoon to the top. The 2nd Platoon, with Ira, Harlon, Mike, and Franklin, was off on a patrol around the mountain’s base and unavailable. As luck would have it, what was left of 3rd Platoon was closest, so these men got the honor of being the first to scale Mount Suribachi. Given a small flag, they were told, “If you get to the top, put it up.”

Sergeant Lou Lowery, a photographer for Leatherneck magazine, volunteered to go along, and up they went, walking and sometimes climbing over boulders, rocks, and debris, cautiously scaling Suribachi’s charred and blackened slopes. After making sure the area was secure and free of booby traps, the 3rd Platoon quickly set about getting the flag up. Everyone was still tense. One leatherneck did take the opportunity to relieve himself over the edge of the crater, declaring, “I proclaim this volcano property of the United States of America.”

A length of drainage pipe was soon located among the rubble, and the flag was attached to it. As three of the Marines planted the pole and Old Glory fluttered over Japanese soil for the first time, the island erupted—not in gunfire but in a deafening chorus of cheers. For a few brief moments, Iwo Jima was transformed into Times Square on New Years Eve. Every Marine on the island was cheering, ships at anchor blasted their horns, and some new guys even thought the battle was over.

It wasn’t. The Japanese holed up inside Suribachi reacted with characteristic fanaticism. They swarmed out of their tunnels and caves, screaming and shooting; one brandished a broken sword over his head. Grenades were going back and forth like a snowball fight. But the flag stayed up, and in a few minutes it was over. All the attacking Japanese were killed, with no loss of American life. A few days later, over 150 dead were found inside the caves. Most had died of self-inflicted wounds.

The secretary of the Navy, James Forrestal, aboard a ship as an observer, had just come ashore and witnessed the event on top of the volcano. He commented, “The raising of that flag on Suribachi means a Marine Corps for the next 500 years.” Forrestal was so impressed that he decided to keep the flag for himself as a souvenir.

The 28th Regiment, however, was going to have no part of that. They had fought too hard to get that flag up there. The regimental commander, Colonel Chandler Johnson, ordered a replacement put up and the first flag brought back down for safekeeping. He then barked at his departing aide, “And make it a bigger one.”

The colonel also decided it would be a good idea to have a wired field telephone on top of the mountain. Having just returned from their uneventful probe around Suribachi’s base, Franklin’s 2nd Platoon was given the job. Although worn out from their mission, nobody complained. While gathering their equipment, they were joined by a runner, Rene Gagnon, who had the new, larger flag. This flag, twice as big as the other one, had been salvaged from a sinking ship at Pearl Harbor.

Taking the Famous Photograph

While all this was going on, an Associated Press photographer named Joe Rosenthal was having a bad day. He had taken a spill in the ocean while climbing into a landing ship and was too late to the mountain to get any pictures of the flag raising. He ran into Bill Genaust, a Marine combat photographer with a color movie camera, and Bob Campbell, another combat photographer. The three decided to climb to the summit of Suribachi anyway; maybe they could shoot a few good pictures.

Arriving on top of the mountain with their wires, telephone, and flag, Strank ordered Hayes and Sousley to locate another usable length of pipe while he and Block cleared a spot to plant the new flag. “Colonel Johnson wants this big flag run up high, so every son of a bitch on this whole cruddy island can see it,” he explained to a nearby officer. As fate would have it, Rosenthal, Genaust, and Campbell arrived on the scene at just this precise moment. It was a few minutes after noon, February 23, 1945.

The journalists noticed two Marines lugging a heavy pipe toward a third Marine holding a neatly folded flag. The plan was to simultaneously lower the first flag while the second flag went up. Campbell placed himself a little downhill to capture this moment, while Rosenthal and Genaust stood about 90 feet away. Block positioned his feet over the spot he had cleared amid the rubble, ready to plant the pipe. Genaust started his movie camera. Strank, the 100-pound pole on his right shoulder, moved toward Block as Hayes joined in. The flag was wrapped around the pipe to keep it from touching the ground. There was nothing ceremonial about the event; they did not even know they were being filmed.

Strank called to Bradley, who dropped his armload of bandages and stepped up to the pole. Sousley then moved into position in front of Hayes. Block leaned over to plant the pole. They gingerly moved the pipe into position, high stepping over the debris as Gagnon entered the picture from the right and joined the cluster of men as they wrestled the new flagpole into position.

Genaust, his camera rolling now, positioned himself a few feet to the right of Rosenthal. “I’m not in your way am I, Joe?” he asked. “Oh no,” Rosenthal replied as he glanced over his shoulder just to be sure. And then, out of the corner of his eye, Rosenthal glimpsed the flag going up. It may be too late! He had to hurry. With no time to frame his shot, Rosenthal reflexively swung his camera up in an arc, pointed, and snapped the photograph.

It was 1/400th of a second, frozen in time—perhaps the most celebrated image of men at war in history. A moment sooner or a split second later, and it might have been just another photo. A good one to be sure, but the flag would not have been at that perfect 45 degree angle. It is the symmetry between the flag and the men that makes this photo such a classic. It looks like the flag is going up, but we cannot be sure it is going to make it. The men are struggling to see that it does go up—and stay there. The image compels casual and interested observer alike to leap into the scene and lend them a hand or cheer them on.

And then it was over. The Marines drove the pipe into the ground and piled rocks around its base while the flag flapped smartly in the breeze. Campbell and Genaust were satisfied; they got the shots they came after. Joe Rosenthal, however, was less enthusiastic. As an experienced photographer, he was well aware of the odds against his photo coming out. It could be all sky, all rocks, possibly out of focus and certainly not centered. As a consolation, he gathered the remaining Marines and took a posed “gung ho” shot. Then everybody went back to work. Rosenthal went out looking for more photos and that night packed up his film and sent it back to the States.

“Practically Secured”

The 28th Regiment spent the next four days resting and licking its wounds, having lost 510 men in the four-day battle to take Suribachi. Since hitting the beach on D-Day, a third of the regiment had fallen in battle. Some men spent their time exploring caves in search of souvenirs; others wrote letters home, and everyone slept.

On February 27, Franklin wrote to his mother Goldie: “As you probably already know we hit Iwo Jima February 19th just a week ago today. My regiment took the hill with our company on the front line. The hill was hard and I sure never expected war to be like it was those first four days. I got some [bullet holes] through my clothing and I sure am happy that I am still OK.

“This island is practically secured. There is some heavy fighting on one end and we are bothered some at night. Mother, you can never imagine how a battlefield looks. It sure looks horrible. I do know of at least four Nips that won’t be going back to Tokyo. Look for my picture because I helped put the flag up. Please don’t worry and write.”

“Here’s One for All Time”

The AP photo editor told his boss, “Here’s one for all time.” He was holding in his hand a picture just back from Iwo Jima of the flag being raised after the Marines conquered Mount Suribachi. However, this picture was different; it wasn’t your everyday news photo. Only one face was visible, the others were all obscured or looking away. Yet it was a masterpiece of composition and lighting. Looking very nearly as if they were carved out of stone, the heroic figures seemed larger than life. They promptly passed it on. On Sunday, February 25, 1945, millions of Americans awoke to find the flag- raising picture on the front page of their newspapers.

Exactly who these men were was anybody’s guess. But Joe Rosenthal became an overnight celebrity. No one back in America yet knew that this was not the original flag raised on Suribachi, but a replacement.

Since Rosenthal was a civilian, his pictures had traveled back to the states much faster than did Lowery’s, which had to pass through military channels. When the truth finally came out it caused a minor scandal, some critics going so far as to accuse Rosenthal of staging the entire scene. He did not, of course, and Genaust’s color motion picture vindicated Rosenthal and silenced his critics.

Flag Bearers Killed in Action

The public also expected that with the taking of Suribachi the battle was all but won. In reality, the opposite was true. The killing would not conclude for another 32 days. On February 28, the 28th Regiment received orders to move directly to the front lines on the western side of the island for a sweep north. A sense of dread soon swelled through the ranks. The next day Easy Company and the rest of the 28th Regiment were thrown back into the horrific nightmare of combat in front of Nishi Ridge, an area strewn with large boulders and shallow, jagged ravines.

The enemy fought with fanatical stubbornness. Every yard won was paid for in blood. It was always the same scenario as before—rattling machine guns; charging, cursing Marines; flames; and screams of appalling agony. Sousley, Hayes, and Block were among maybe a half dozen men under Strank’s command who came under a withering fire from a nest of Japanese snipers. Pinned down behind a formation of large, jagged rocks, which offered protection on three sides, their only opening was to the sea where American destroyers were laying down a heavy covering fire on Japanese positions.

“You know, Holly, that’s going to be one hell of an experience,” Mike dryly observed to one of his men while gazing upon a fallen comrade a few yards to their front. A moment later, their world exploded. Sousley and Block were knocked down by the blast but unhurt; a few others received serious head and chest wounds. All were stunned by the explosion. When the smoke cleared, everyone’s worst nightmares were realized. There on the ground lay Strank, a hole blown right through his chest where his heart had been. As twilight settled on March 1, the 28th had gained a meager 300 yards. Block was killed by a mortar round late in the day.

Reactions to the Photograph

On the same day, U.S. Congressman Joseph Hendricks of Florida rose from his seat in the House of Representatives and introduced a bill authorizing the construction of a monument. It would be a tribute “to the heroic action of the Marine Corps as typified by the Marines in this photograph. I have provided in the bill that this picture be a model for the monument because I do not believe any product of the mind of the artist could equal this photograph in action. Never have I seen a more striking photograph.”

By the time the sun set, Nishi Ridge had finally fallen. Only after the battle was over did the Marines discover that it was as heavily fortified as Mount Suribachi. Just over 200 feet high and stretching nearly to the western shoreline, it featured 100 camouflaged cave entrances and was manned by 1,000 of Kuribayashi’s best troops. Inside, the Marines found an elaborate tunnel network.

On March 5, 2nd Battalion was pulled back for a couple of days of rest. Halfway around the world, the latest edition of Time magazine hit the newsstands with the photograph on the cover along with the caption, “TO RANK WITH GETTYSBURG, VALLEY FORGE AND TARAWA.”

Two days later, as Franklin and the shattered remnants of Easy Company headed back to the killing fields of northern Iwo Jima, Representative Mike Mansfield of Montana proposed on the House floor that the photograph be made the official symbol of the Seventh War Bond Tour.

On March 14, Iwo Jima was declared secure, although the Marines were still fighting pockets of resistance. Disabled American bombers were beginning to make emergency landings on the island, and by war’s end 2,400 would find a haven there, saving the lives of 27,000 crewmen.

Franklin Sousley KIA

A total of 24,127 Marines had been lost so far, 4,189 killed in action, and 19,938 wounded. Iwo Jima had now become the deadliest battle in the Marine Corp’s 168-year history. Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, commander in chief of the U.S. Navy in the Pacific, stated, “Uncommon valor was a common virtue.”

For Sousley and Hayes, it had been a very hard time. In combat for 20 of the last 26 days, they were the two surviving Easy Company flag raisers. They had watched as their comrades, one by one, fell in battle.

On March 21, Sousley was killed in action. The bullet hit him square in the back and shattered his spine. His buddies dove for cover as Franklin swatted absently at his shirt, as if brushing away a fly, while collapsing. “How ya doin?” one shouted. “Not bad,” Franklin replied, “I don’t feel anything.” And then he died.

The Kentucky farmboy turned factory worker, who had survived 30 days of combat and had been transformed from happy-go-lucky teenager into hardened combat veteran, lay dead. He never saw the famous photograph, never even knew of its existence. He was 19 years old.

Easy Company was pulled back from the front line three days later, just two days before the Battle of Iwo Jima reached its conclusion. Of the 310 men of Easy Company that hit the beach some 36 days previously, only 50 were left.

On Monday, April 9, a telegram bearing the awful news arrived in Hilltop, Kentucky. Word of Franklin’s death soon raced like a wildfire through the countryside. Marian Hamm solemnly packed up all of Franklin’s personal effects and walked them over to Goldie’s house. Marian was still young and knew someday she would get over this tragic chapter in her life, but what about poor Goldie, what would she ever do? Her neighbors reported hearing Goldie’s screams all through the night and into the next morning. Their home was a quarter-mile away.

The Aftermath of Iwo Jima

The final toll at Iwo Jima staggers the imagination. Out of Chandler Johnson’s 2nd Battalion, which numbered 1,688 men at its peak, only 177 walked off the island. In 36 days of battle, 25,851 Marines fell in combat. Of these, 6,821 died and were buried in a makeshift cemetery at the base of Mount Suribachi. Franklin was interred in Grave No. 2189, Mike Strank rested in Grave 694, and Harlon Block was buried in Grave 912. It took 10 years to have all the bodies exhumed and brought home to the United States.

Japanese losses were 21,000 killed; most were entombed underground in the same caves in which they fought and died. Only 1,000 survived to be taken prisoner. The last two defenders did not surrender until 1949.

Iwo Jima was perhaps the most ferocious battle our nation has ever fought. There were larger battles and longer fights, to be sure, but nothing quite like this eight square miles of lunar-like landscape. More medals for valor were awarded here than for any other conflict in U.S. history. One-third of the 84 Medals of Honor awarded the Marine Corps in all of World War II were earned on Iwo Jima.

John Bradley, Rene Gagnon, and Ira Hayes became national heroes and thus were the centerpiece of the Seventh War Bond Tour. Massive, cheering throngs greeted them wherever they went, large city or small. Ironically, they did not consider themselves heroes, and all were very public about it. The real heroes were those men who did not return, all their buddies who were still back there, still on the island. They were just part of an accidental photograph.

Franklin Runyon Sousley was buried in the Elizaville Cemetery on a beautiful, sunny Saturday morning, May 8, 1947. As the Marine escort gently lowered his body into its final resting place, local veterans fired a salute, and a lone bugler played taps. The governor of Kentucky stepped forward to hold Goldie’s hand as she said her last goodbye to the son she loved so much. The grave was marked with a simple stone tablet. Forty years later, a group of Marine veterans took it upon themselves to raise funds for a new marker, this one befitting the man and those who served with him.

First-time contributor Randall B. Ingram is the president of the Franklin R. Sousley-Iwo Jima Memorial Freedom Fund. He works in the General Motors facility in Dayton, Ohio, where Sousley was once employed. Ingram credits James Bradley’s bestseller Flags of Our Fathers with providing information for this story.

Further investigation proved that neither Gagnon or Bradley helped raised the second flag On Iwo.