By Al Hemingway

On May 12, 1975, an American-registered cargo ship, the SS Mayaguez, was suddenly fired upon by Cambodian gunboats and later seized by Khmer Rouge soldiers who boarded her. The incident would spark an intense battle on the nearby island of Koh Tang. When the smoke cleared, some 41 Americans had been killed and another 50 wounded. The fate of three missing servicemen is shrouded in mystery to this day.

In their new book, The 14-Hour War: Valor on Koh Tang and the Recapture of the SS Mayaguez (Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2011, 320 pp., photographs, notes, index, $34.95, hardcover), authors James E. Wise, Jr., and Scott Baron scrutinized what happened during those anxious moments in what many have referred to as the “last battle of the Vietnam War.”

Following the seizure of the 500-foot vessel, the crew of the Mayaguez was transferred to another ship. Unfortunately, U.S. aircraft mistakenly reported that the 39 crewmen were being held on Koh Tang Island, 30 miles off the coast of Cambodia. In fact, they had been freed and put aboard a Thai fishing boat.

On May 14, a Corsair pilot had reported that he observed Caucasians aboard the fishing vessel and that was it accompanied by three Cambodian gunboats. The authors assert that “intelligence could provide no definitive answer as to whether any, part, or all of the crew was on board the fishing boat, on Koh Tang, on neither, or on both.” A lack of reliable intelligence, an overlapping chain of command, and a cumbersome joint service command and control element all contributed to the military disaster that was to follow.

Late in the afternoon of May 14, President Gerald R. Ford gave the green light for a force of U.S. Marines to board Mayaguez and assault Koh Tang Island. Just after 7 am, two A-6 Corsairs unleashed chemical agents over the ship, which was lying stationary in the water off the Cambodian coast. As the USS Holt edged her way next to the vessel, Lt. Cmdr. John Todd ordered the leathernecks over the side, the first time the Marines had boarded an enemy vessel since the Civil War.

Within minutes, the infantrymen were scurrying on the decks and into the hold of the cargo ship, but found it deserted. In a little more than an hour, the boat had been secured. Unfortunately, the Marines who had stormed ashore on Koh Tang were not having such an easy time of it. The assault troops landed on the northern tip of the pork chop-shaped island on two separate beaches and were greeted with intense fire from an estimated enemy force of 250.

For the next 14 hours, the Marines and Khmer Rouge battled it out before the order to extract the landing force was finally given. In the confusion, three Marines were inadvertently left behind and declared dead years later by a Department of Defense investigation.

What makes the authors’ account really come to life is the recollections from the individuals who participated in the operation, especially from Em Son, the Khmer Rouge officer who led the enemy force on Koh Tang. Son talked to investigative reporter Ralph Wetterhahn, who spent five years studying information as to the whereabouts of the three missing Marines—Lance Corporal Joseph N. Hargrove, PFC Gary Hall, and PFC Danny G. Marshall. Son contends that Hargrove was fatally wounded in the leg and was buried near a mango tree where he fell. Marshall and Hall, the Cambodian officer contends, were captured later trying to steal food and transported to Khmer Rouge 3rd Division headquarters in Kompong Som. Son claims that the two were beaten to death.

Because of the acidic soil, bone fragments later uncovered cannot be positively identified as those of the three missing Marines. “Unless the remains of the three Marines can be identified through DNA and dental comparisons, we might never know what happened to these brave men,” the authors state. Somehow, it seems a fitting end to the entire Vietnam experience.

1812: The Navy’s War by George C. Daughan, Basic Books, New York, 2011, 512 pp., illustrations, notes, bibliography, $37.50, hardcover.

1812: The Navy’s War by George C. Daughan, Basic Books, New York, 2011, 512 pp., illustrations, notes, bibliography, $37.50, hardcover.

The War of 1812 has often been referred to as America’s Second War of Independence, and rightfully so. Since gaining its freedom from Great Britain, the fledgling United States received little respect from the British. Issues such as trade restrictions, expansion in the Northwest Territory (present-day Indiana, Michigan, and Illinois), and the impressment of American seamen into the British Navy reached a boiling point and war was finally declared by President James Madison.

With few exceptions, the American Army had little success against the British regulars. Badly defeating the Americans at Bladensburg, Maryland, the Redcoats marched unimpeded to Washington and burned the nation’s capital. Meanwhile, the American invasion of Montreal and other forays into Canada proved fruitless, and the fighting in the Northwest Territory was also more or less a failure.

It was the small but feisty Navy that really was the shining star for the United States during the conflict. Composed of an odd mix of bright and energetic commanders; dedicated seamen, many of whom were British deserters; and a ragtag group of privateers, the Americans racked up some impressive victories at sea. Even British naval leaders, who believed themselves with some justice the ruler of the waves, developed a grudging respect for men such as Stephen Decatur, Isaac Hull, and Oliver Hazard Perry.

Important points emerged from the conflict. President Madison realized the need for a strong army and navy to show the world that the United States was serious about defending herself against foreign aggression. Many Americans had wrongly thought that a powerful armed force would undermine the Constitution, but after the war, many viewed the issue much differently in light of the country’s new-found military prowess.

As Treasury Secretary Albert Gallatin said after the war had ended, “I hope that the permanency of the Union is thereby better secured.” That statement would hold true for another half a century, until another bloody war—this one internal—would once again threaten the American people.

Lions of the West: Heroes and Villains of the Westward Expansion by Robert Morgan, Algonquin Books, Chapel Hill, NC, 2011, 496 pp., illustrations, notes, bibliography, $28.95, hardcover.

Lions of the West: Heroes and Villains of the Westward Expansion by Robert Morgan, Algonquin Books, Chapel Hill, NC, 2011, 496 pp., illustrations, notes, bibliography, $28.95, hardcover.

America’s westward expansion is filled with tales of adventure, heroism, and downright skullduggery perpetrated by both the government and individuals, particularly against the Native American peoples who already resided here. In his book, historian Robert Morgan traces the westward movement through the actions of 10 individuals, beginning with Thomas Jefferson, the “quintessential American dreamer,” and John Quincy Adams, who severely criticized the government’s handling of the westward movement.

No doubt, one of the biggest contributors to the westerly trek of the American pioneers was Andrew Jackson, himself a native of the southwestern frontier. “Old Hickory’s” victories against the Creek Indians and his forced relocation of the Cherokees in 1832 allowed white settlers to encroach upon native land. His desire to drive the Cherokees from their homes is still remembered today as the “Trail of Tears,” where thousands perished as they made their way to Oklahoma.

Jackson’s protégée, President James K. Polk, did more in his one term as the nation’s chief executive to promote and acquire millions of acres of land than, arguably, any other American leader in history. Using the military, he defeated Mexico and took huge tracts of land in present-day Arizona, New Mexico, California and Texas. Polk also settled a long-festering border dispute in the Northwest with the British without firing a shot.

Morgan writes a wonderful account of John Chapman, aka Johnny Appleseed, who walked the wilderness carrying sacks of apple seeds to plant. Chapman’s love of the outdoors and the sense of freedom he felt when he wandered through the wilderness were shared by thousands of other unsung Americans who left their homes in the East to settle a new land out West.

Morgan writes that America’s “aggressive expansion is evidence of a preoccupation with the future, not the present.” Maybe, Morgan writes, Americans can channel that energy and passion toward effective, essential, and better goals in today’s world. One can only hope.

This Great Struggle: America’s Civil War by Steven E. Woodworth, Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Lanham, MD, 2011, 407 pp., illustrations, maps, notes, index, $29.95, hardcover.

This Great Struggle: America’s Civil War by Steven E. Woodworth, Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Lanham, MD, 2011, 407 pp., illustrations, maps, notes, index, $29.95, hardcover.

Civil War historian Steven E. Woodworth gives readers a workmanlike synopsis of the four years of Civil War and what he terms the “great struggle” that ensued after the conflict had ended—Reconstruction.

The question has always been posed, Woodworth states, would reconstruction have gone differently if Abraham Lincoln had not been assassinated? No one can say for sure, but the author makes a valid argument that “Lincoln would no doubt have needed every bit of his skill to navigate the difficult political waters of Reconstruction,” unlike his successor, President Andrew Johnson, who Woodworth says “was lost at sea.”

For more than a decade, Northerners and Southerners still battled over what rights former slaves should possess and what form of government should be instituted in the Southern states. As the author states, even some Northern states were reluctant to give blacks the right to vote and own property.

In the end, the fickle American public in the North grew weary of the incessant struggle and just wanted to get on with their lives. To them, the Union had been preserved and slavery had been abolished, even if African Americans had not been fully accepted as truly free citizens. It was almost as if the war had never been fought.

War’s Waste: Rehabilitation in World War I America by Beth Linker, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL, 2011, 291 pp., illustrations, notes, index, $35, hardcover.

War’s Waste: Rehabilitation in World War I America by Beth Linker, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL, 2011, 291 pp., illustrations, notes, index, $35, hardcover.

The dust cover of this book is heart-wrenching. It shows two World War I soldiers, their faces partially obstructed. One doughboy, missing his left leg, is lighting a cigarette for another, who has no arms. The cover forcefully illustrates the brutality and insanity of war.

Out of the catastrophic injuries suffered by America’s youth during the “war to end all wars” emerged the Veteran’s Administration and other programs created to aid disabled servicemen and help them become productive members of society. However, as the author writes, not all went smoothly. Proponents of reform of the system wanted soldiers not only to receive medical care, but also to be provided vocational training that would enable them to be self-sustaining, not just become wards of the government.

Linker uses Garth Stewart, a soldier who lost his leg in Iraq, as a prime example. “By his own accord, he is always at work, whether in school, at fundraising events, or at the gym,” she writes. “He rarely sits still. The Progressive reformers who legislated and instituted rehabilitation could not have imagined a more ideal disabled soldier-patient. He is their dream made real.”

Black Ops Vietnam: The Operational History of MAVCSOG by Robert M. Gillespie, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2011, 320 pp., photographs, notes, index, $41.95, hardcover.

Black Ops Vietnam: The Operational History of MAVCSOG by Robert M. Gillespie, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2011, 320 pp., photographs, notes, index, $41.95, hardcover.

Nothing about the Vietnam War is more shrouded in secrecy than the black operations, or black ops, performed by the members of the Special Operations Group. This fascinating account delves into these highly classified actions and the group, comprising all branches of the military and civilian agencies of the government, which executed them during the war.

From the beginning of the conflict through the 1968 Tet Offensive, incursions into Laos and Cambodia, and the mysterious Phoenix Program, SOG teams were everywhere in Southeast Asia. Teams also used the military skills of the Chinese Nungs, Montagnards, South Vietnamese soldiers, and Taiwanese pilots to carry out their missions.

Gillespie’s book is particularly timely in light of the ongoing fighting in Iraq and Afghanistan. It demonstrates the hazardous duty that SOG teams endure, as shown by the recent tragic downing of a Chinook helicopter that killed 30 Americans involved in clandestine operations in that part of the world.

Hesitation Kills: A Female Marine Officer’s Combat Experience in Iraq by Jane Blair, Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc., Lanham, MD, 2011, 286 pp., $24.95, hardcover.

Hesitation Kills: A Female Marine Officer’s Combat Experience in Iraq by Jane Blair, Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc., Lanham, MD, 2011, 286 pp., $24.95, hardcover.

When we talk about the Post Traumatic Stress Disorder that thousands of returning service personnel have suffered to some degree as long as Americans have been involved in warfare, we tend to think of it as a male-dominated group. With the rise of females in the military, however, the psychological stress caused by warfare can affect them as well.

Women make up about 14 percent of all branches of the military, or approximately 400,000 troops. To date, 113 have been killed in Iraq and Afghanistan and more than 600 have been wounded. Blair’s book brings home the alienation that many combat veterans feel when they return to the United States. Most have gone through a metamorphosis that only those who have “seen the elephant” can understand.

“It was hard to venture out into the civilian world,” Blair writes. “I began to wonder if my perception of the world would ever return to what it had been.” Blair delivers a powerful account that tells Americans that PTSD-related feelings of hopelessness, nightmares, and fears have no gender boundaries.

Washington: A Legacy of Leadership by Paul Vickery and Stephen Mansfield, Thomas Nelson, Nashville, TN, 2011, 224 pp., bibliography, notes, $19.99, hardcover.

Washington: A Legacy of Leadership by Paul Vickery and Stephen Mansfield, Thomas Nelson, Nashville, TN, 2011, 224 pp., bibliography, notes, $19.99, hardcover.

What more can be said about George Washington? Judging from this book, it seems quite a bit. Another in the series “The Generals” by Thomas Nelson Publishers, George Washington makes an always compelling subject.

The authors trace Washington’s life from his childhood in Virginia to his service with the British during the French and Indian War, as commander in chief of the Continental Army, his presidency, and death in 1799. Washington led by example. He could administer cruel punishment, including hanging, but he was extremely fair in his deliberations. He once said that he must “reward and punish every man according to his merit, without partiality or prejudice.” He felt that soldiers should be led, not driven, by their leaders.

When news of his death reached Thomas Jefferson, the author of the Declaration of Independence and future president wrote to a friend, “Verily a great man hath fallen this day in the house of Israel.” It was an unusually religious reference by the agnostic Jefferson, but it reflected the almost holy reverence in which “the Father of His Country” was held by all Americans.

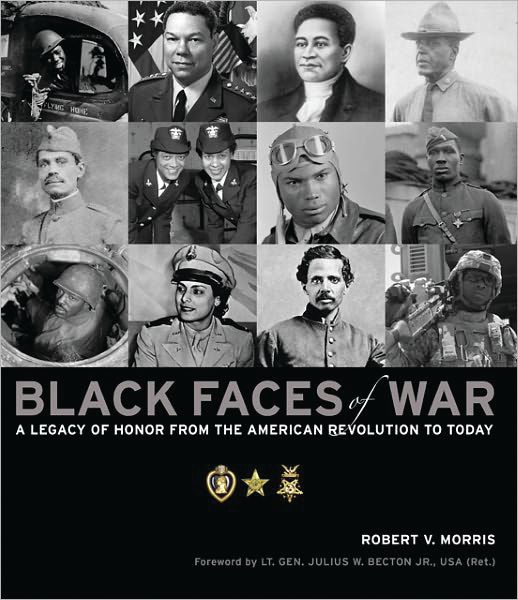

Black Faces of War: A Legacy of Honor from the American Revolution to Today by Robert V. Morris, Zenith Press, Minneapolis, MN, 2011, 160 pp., photographs, index, $30.00, hardcover.

Black Faces of War: A Legacy of Honor from the American Revolution to Today by Robert V. Morris, Zenith Press, Minneapolis, MN, 2011, 160 pp., photographs, index, $30.00, hardcover.

If one takes a close look at the famous painting of Washington crossing the Delaware by German American artist Emanuel Gottlieb Leutze, you will notice a freed black man, Oliver Cromwell, at the oar behind the general’s knee.

The author, the grandson and son of decorated U.S. Army officers, has written a marvelous tribute to the African American servicemen and women who have served the American cause since its struggle for independence from Great Britain more than 200 years ago.

As Morris writes, it was black men such as Cromwell and Crispus Attucks, killed in the Boston Massacre in 1770, who paved the way for other African Americans to fight alongside whites as a part of the U.S. armed forces. The nation is much the richer for it.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments