By Al Hemingway

When Chief Aerographer’s Mate Richard Klos volunteered for “prolonged and hazardous” overseas duty, he had no idea what he was in for. However, when he was questioned about his ability to live on vermin or if he could tell the difference between edible and toxic lice, he knew he had signed on for something special.

And special it was. Klos and thousands like him were to play an important part in the U.S. Navy’s efforts to gather pertinent data from behind enemy lines in China. The top secret group was known as the Sino-American Cooperative Organization, or SACO, a bunch of 2,500 “individualists” who brought war to the Japanese in China. In her new book, The Rice Paddy Navy: U.S. Sailors Undercover in China (Osprey Publishing, Long Island City, NY, 2012, 294 pp., photographs, notes, index, $24.95, hardcover), author Linda Kush gives the reader an engrossing tale of these innovative sailors who served in a theater of the war that remains largely forgotten.

And special it was. Klos and thousands like him were to play an important part in the U.S. Navy’s efforts to gather pertinent data from behind enemy lines in China. The top secret group was known as the Sino-American Cooperative Organization, or SACO, a bunch of 2,500 “individualists” who brought war to the Japanese in China. In her new book, The Rice Paddy Navy: U.S. Sailors Undercover in China (Osprey Publishing, Long Island City, NY, 2012, 294 pp., photographs, notes, index, $24.95, hardcover), author Linda Kush gives the reader an engrossing tale of these innovative sailors who served in a theater of the war that remains largely forgotten.

The Joint Chiefs of Staff were eager to learn more about weather conditions, troop movements, and the size of enemy units throughout China. This information would prove to be extremely valuable when the time came for Allied forces to invade China and defeat the Japanese forces stationed there. As the war progressed, China was put on the back burner, so to speak, and instead the Allies placed much emphasis on the island-hopping campaigns of Admiral Chester Nimitz and General Douglas MacArthur, that would include the latter’s triumphant return to the Philippines in 1944.

Nevertheless, SACO’s members were resourceful when requisitioning supplies, equipment, food, and anything else they needed throughout the war. That ingenuity came right from the top with SACO’s commander, Captain Milton “Mary” Miles, a U.S. Naval Academy graduate who had served in China during the 1920s and 1930s on the river patrol boats scurrying up and down the Yangtze River. Miles developed a sincere interest in the Chinese people and their traditions. When he was given command of SACO, he fought against having any of the old “China Hands” included in his group because he witnessed firsthand their disdain for the land and its people.

The lack of supplies and personnel was not the only problems Miles faced. The constant bickering between the Army, Navy, and the newly formed Office of Strategic Services led by the World War I hero and hard-charging Brig. Gen. William J. Donovan, was a thorn in Miles’s side. Miles constantly circumvented the command structure, risking his career, to provide for his men.

Miles formed an unlikely alliance with General Dai Li, the leader of Nationalist China’s Military Bureau of Investigation Services and Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek’s right-hand man. Dai Li learned to trust Miles while Miles, had to overcome his fears that his counterpart was a diabolical executioner based on reports he had read prior to assuming command of SACO.

Kush delivers a readable and exciting story of a military unit that truly had to fight to maintain its existence. The sailors, often dressed in worn-out Army fatigues, were responsible for transmitting top secret messages to Allied planners, participating in raids on Japanese vessels traveling along China’s many rivers and training Chinese guerrillas who performed behind-the-lines forays that kept the enemy off balance.

Known for its irreverent “What the Hell?” banner, a pennant with three question marks, three asterisks, and three exclamation points emblazoned on a white background, SACO did an incredible job despite its many setbacks.

This is a wonderful tribute to a group of mavericks who did not play by the book and performed a remarkable job in helping to defeat the Japanese in China in World War II.

Leyte 1944: The Soldiers’ Battle by Nathan N. Prefer, Casemate Publishers, Havertown, PA, 2012, 424 pp., maps, photographs, notes, index, $32.95, hardcover.

Leyte 1944: The Soldiers’ Battle by Nathan N. Prefer, Casemate Publishers, Havertown, PA, 2012, 424 pp., maps, photographs, notes, index, $32.95, hardcover.

Finally, a definitive account of the battle that wrested the island of Leyte in the Philippines from the Japanese in 1944 has emerged. Although much has been written about the U.S. Navy’s role at Leyte, the savage, bloody fighting that took place on land has been overlooked.

Fulfilling his pledge to return after he had been forced to leave the Philippines by PT-boat in early 1942, General Douglas MacArthur pushed the idea of a return to the Philippines with the Joint Chiefs and President Franklin Roosevelt. MacArthur’s persistence paid off as soldiers from the Sixth Army, aided by Filipino guerrillas, fought the Japanese from late October 1944 until the beginning of 1945. More than 200,000 Americans not only fought a seasoned enemy but had to endure harsh tropical weather with its incessant monsoon rains and typhoons as well.

Two prominent officers who deserve the lion’s share of the accolades are General Walter Krueger, commanding the Sixth Army, and General Robert Eichelberger, leading the Eighth Army. Both had battlefield experience and did a marvelous job as their troops fought at places with names such as Breakneck Ridge, Shoestring Ridge, and Ormoc Valley. In a highly unusual move, the Japanese used airborne infantry to parachute behind the American lines to disrupt the flow of supplies and conduct raids.

Prefer has penned a meticulous book, complete with the order of battle for each side, a breakdown of U.S. casualties, detailed maps, and 16 photographs. It is a fitting story chronicling the bravery and sacrifices of the dogface GI, and the nearly 3,500 killed and another 10,000 wounded, who beat the very best that the enemy could throw at them and freed the inhabitants of Leyte from a brutal occupation.

Letters from Berlin: A Story of War, Survival, and the Redeeming Power of Love and Friendship by Margarete Dos and Kerstin Lieff, Lyons Press, Guilford, CT, 2013, 358 pp., photographs, notes, $24.95, hardcover.

Letters from Berlin: A Story of War, Survival, and the Redeeming Power of Love and Friendship by Margarete Dos and Kerstin Lieff, Lyons Press, Guilford, CT, 2013, 358 pp., photographs, notes, $24.95, hardcover.

This is a truly moving story of a German woman who survived the war while residing in Berlin. Margarete Dos was born in Germany in 1924 and was just a young child when Hitler rose to power. She eventually migrated to the U.S. but refused to talk about the years she spent in Germany during the conflict. After some prodding, Dos related those horrific years to her daughter, Kerstin Lieff, who spent hours with her mother recording her incredible story of survival.

As a teenager growing up in Berlin, Dos witnessed firsthand the growing Nazi menace. At first it was subtle, as the SA arrogantly paraded through the streets. Their condescending attitude only drew laughs from Dos and her friends. However, as the years crept by, their antics turned deadly. Dos explains what she saw during that turbulent period in German history—the Night of the Broken Glass when Jewish businesses were ransacked and looted, the Allied bombings, and the fear of the Russians—in graphic detail.

This is another fascinating side of World War II told through the eyes of an innocent young girl growing up amid the chaos and savagery of war.

Defending Whose Country? Indigenous Soldiers in the Pacific War by Noah Riseman, University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln, 2012, 336 pp., photographs, notes, index, $50.00, hardcover.

Defending Whose Country? Indigenous Soldiers in the Pacific War by Noah Riseman, University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln, 2012, 336 pp., photographs, notes, index, $50.00, hardcover.

This is a thought-provoking look at the role the indigenous tribes played in helping the Allies defeat Japan in World War II. To the theater commanders, it made perfect sense to utilize these indigenous people because of their intimate knowledge of the countryside, their fighting skills, and their ability to withstand hardships that many of their white counterparts had never experienced before.

Ironically, many Australians and other white “mastas” residing on New Guinea were not keen on allowing indigenous people to serve. It was only when the Japanese posed an imminent threat to the region that this stand was eased, and numerous tribes served as guides, coastwatchers, and in units led by Allied officers.

The United States, on the other hand, encouraged Native Americans to enlist in the armed forces. Although many tribes had been mistreated and lied to by the government, they joined to fight willingly. Probably the most notable group was the Navajos, whose unique language was used to transmit messages and confuse the Japanese. Many of the Navajo have become popularly known as the Code Talkers.

The author has tackled a complex issue and has done a masterful job of explaining the relationships between Caucasians and the indigenous people who served with them. The book is a nice tribute to their largely forgotten contributions to the war effort, which assisted in the ultimate defeat of the Japanese Empire.

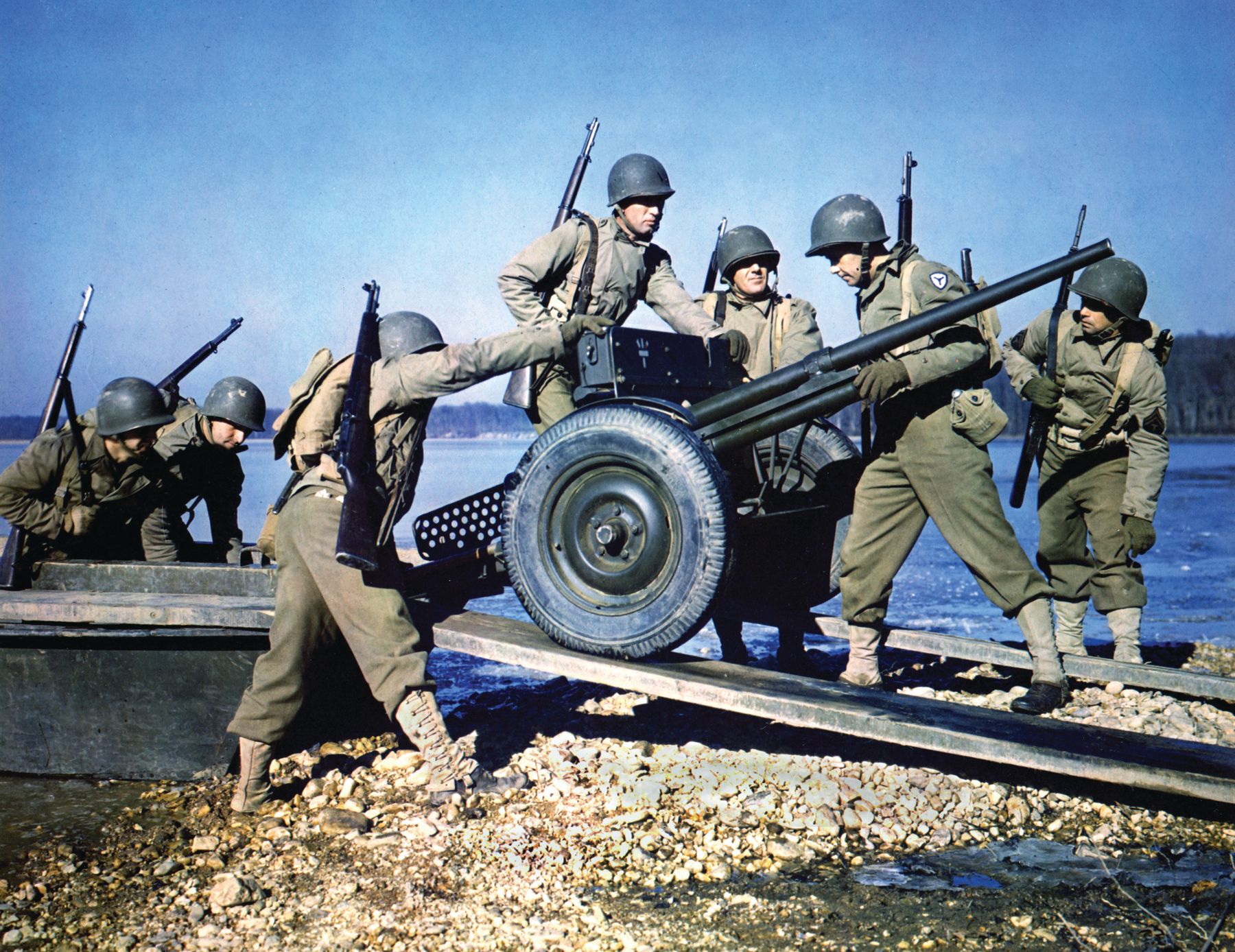

From Brittany to the Reich: The 29th Infantry Division in Germany, September-November 1944 by Joseph Balkoski, Stackpole Books, Mechanicsburg, PA, 412 pp., maps, photographs, notes, index, $26.95, hardcover.

From Brittany to the Reich: The 29th Infantry Division in Germany, September-November 1944 by Joseph Balkoski, Stackpole Books, Mechanicsburg, PA, 412 pp., maps, photographs, notes, index, $26.95, hardcover.

Historian Joseph Balkoski has written a marvelous account giving long, overdue praise to the infantrymen of the “Blue and Gray,” the 29th Infantry Division, in World War II. This is his third book, covering the period from September to November 1944, with two more to follow covering the division’s exploits to the end of the war.

The dogfaces of the 29th Division suffered horrendous casualties after spearheading the D-Day invasion on June 6, 1944. From there, they saw extensive combat in the hedgerows and St. Lo and fought fanatical German paratroopers in the city of Brest so the Allies could use its important port facilities for resupply.

Balkoski traces the unit’s operations into Holland and eventually western Germany. In mid-November, the 29th drove to the Roer River, where the soldiers tangled with German soldiers in numerous intense, bloody battles within what would later become known as the “Roer Triangle.” Little has been written about this part of the European Theater, and the author gives the reader a good overview of the precarious world of a rifleman in the 29th Division and the dangers he faced day in and day out while helping to defeat a tenacious enemy.

The Star of Africa: The Story of Hans Marseille: The Rogue Luftwaffe Ace Who Dominated the WWII Skies by Colin D. Heaton & Anne-Marie Lewis, Zenith Press, Minneapolis, MN, 2012, 224 pp., photographs, notes, index, $30.00, hardcover.

The Star of Africa: The Story of Hans Marseille: The Rogue Luftwaffe Ace Who Dominated the WWII Skies by Colin D. Heaton & Anne-Marie Lewis, Zenith Press, Minneapolis, MN, 2012, 224 pp., photographs, notes, index, $30.00, hardcover.

This is a fascinating biography of one of Germany’s top guns during the North African campaign early in World War II. Hans Joachim Marseille downed 25 Allied aircraft and was awarded the coveted German Cross in Gold. He had joined the Luftwaffe prior to the war and was a skilled aviator. He loved the ladies, drinking, and staying out until the wee hours of the morning, which did not sit well with his commanding officers.

Dashing and handsome, Marseille was a charmer. However, he was transferred on several occasions when his antics proved to be too much. It was not until he was reassigned to North Africa that he really emerged as a top notch pilot. He quickly earned the sobriquet of the “Star of Africa.”

His endearing ways earned him many friends. He never joined the Nazi Party and, instead, waged his own chivalrous style of warfare. This was indeed ironic. Here was a man like Marseille, who personified everything that was not Nazi and avoided persecution or imprisonment for his beliefs. He was killed when his plane developed engine trouble in September 1942. Although he was able to escape, he could not open his parachute.

This is an entertaining book dealing with a unique and complex person. As the subtitle suggests, Marseille was certainly a rogue who earned the respect and admiration of his fellow aviators.

Why Germany Nearly Won: A New History of the Second World War in Europe by Steven D. Mercatante, Praeger, Santa Barbara, CA, 2012, 409 pp., maps, notes, index, $58.00, hardcover.

Why Germany Nearly Won: A New History of the Second World War in Europe by Steven D. Mercatante, Praeger, Santa Barbara, CA, 2012, 409 pp., maps, notes, index, $58.00, hardcover.

Most people will agree that Hitler’s misguided invasion of Russia in 1941 was Germany’s undoing. The German Army paled in comparison to the Soviets, numerically speaking, and historians believe that this brought about the downfall of the Third Reich.

Or did it? The author, Steven Mercatante, editor-in-chief of The Globe at War, a website that examines World War II, thinks otherwise. In this book, he attempts to explain why Germany came within a “whisker” of winning not only the conflict but creating a vast European empire for the Nazi regime. One of the major reasons that Germany lost, states the author, is that military commanders did not seize the region of the Soviet Union rich in economic resources, such as oil. Because of this, the Wehrmacht “lost much of the preexisting qualitative advantages that it held over its enemies.”

Although the Allies outnumbered the German Army in terms of manpower and machinery, the Wehrmacht had racked up some impressive victories early in the war, but when it needed to deliver the knockout punch in Russia it failed to do so.

This is an intriguing book that will surely be of great interest to students of World War II. It offers a fresh analysis of why Germany was beaten and poses reasons why it should have won.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments