By Hervie Haufler

Some accounts of Ian Fleming’s life make it seem that only at the age of 44, as an antidote to the shock of finally agreeing to get married, did he suddenly commit himself to the unplanned task of creating his James Bond novels. In actuality, he had declared his interest in writing thriller-type books as early as the age of 20, when he confided to his friend Ivar Bryce that this was his lifetime goal. Even that early he had begun collecting incidents and experiences that he could later weave into his 13-book saga of James Bond.

Most particularly, Fleming relied on his richly varied participation in World War II as source material for Bond’s exploits. Rather than tie his hero to history, though, he made Bond current by involving him in the Allies’ Cold War struggle against the Soviet Union.

Early Experiences in Switzerland

Ian grew up in the shadow of his talented older brother, Peter. Both were mere boys when their father was killed in World War I. As the oldest of four brothers, Peter felt the need to become the male head of the family. His sense of responsibility drove him to excel as a student at Eton and Oxford. Soon he began turning out best-selling books on his travels to far places. Also, he married the beautiful actress Celia Johnson. He made himself a very hard act to follow.

In response, Ian appeared not even to try. He became a rebel against standard paths of achievement. His mother, Eve, considered him her problem child. Attending Eton, he made his mark in sports rather than academics. Concerned by his mediocre grades and his misadventures, Eve had him placed in Eton’s Army Class. Then, because of an escapade with a local girl, he left without graduating, and, at Eve’s insistence, signed up for military officer training at Sandhurst. There, too, he rebelled against the routines and left, under a cloud because of another amorous infraction, without a commission. It was the same when Eve tried to get him into the Foreign Office. He did study for the essential entrance exam and did reasonably well but did not rank high enough to win a job as a diplomat.

It was only when he got out from under his mother’s watchful eye and away from the intimidating example of his brother that Ian came into his own. This happened when Eve, giving up on any other course, sent him to Kitzbühel, Switzerland, to study under an English couple there. Ernan Forbes-Dennis and his wife, who wrote novels under her maiden name of Phyllis Bottome, were running an idealistic school that sought to straighten out troubled adolescents. They realized Ian’s potential and took a special interest in him. As a result, he found himself discovering a great facility for languages as well as a love of reading. In Kitzbühel, under the Forbes-Dennis duo, he acquired the equivalent of a university education.

Young Ian also entered into his first serious romance, with a beautiful Swiss girl. When that attachment ended, incurring hard feelings on both sides, Ian declared that he was “going to be quite bloody-minded about women from now on” and would take what he wanted “without any scruples at all.” Aside from his enduring love for Ann O’Neill Rothermere, his new attitude led to innumerable affairs over many years. He endowed Bond with that same low opinion of women as anything other than temporary bedmates.

Fighting the war in the Naval Intelligence Division

Now confident of his own abilities, Fleming secured a job as a reporter for the Reuters news agency. He did well enough that, after a year, he was sent to Moscow to cover the trial of six British engineers arrested on trumped-up charges by the Soviet secret services. The stories he wrote helped raise an uproar of anger in Britain that induced the Soviet leaders to back down and release the engineers. His reporting also brought offers from other journals.

But the terms of his father’s will left Ian unable to live in the style he enjoyed, and journalism was unlikely to provide the income necessary to sustain that lifestyle. With the war clouds gathering, he turned down the writing prospects and took a position in banking. Although the financial life soon bored him, it was a fortuitous move because the banking background helped him win his World War II assignment.

In early 1939, Rear Admiral John Godfrey had received the opportunity to top his distinguished Royal Navy career by becoming the head of the Naval Intelligence Division (NID) of the Admiralty. Needing a strong personal assistant, he sought the advice of his NID predecessor, Sir Reginald “Blinker” Hall. Hall had relied on a personal assistant with a banking background. So advised, Godfrey selected Ian out of a list of promising comers with financial experience.

When, at the age of 31, Fleming joined the NID, he was described as a “striking young man,” with charm, vitality, a sense of adventure, enthusiasm, and “a certain confidence and authority.” He came aboard NID as a lieutenant but, with Godfrey’s approval, quickly advanced to the rank of commander. For the first time, Ian really loved his work, devoured it, and did such unimaginable things as arriving at his desk at 6 am every day.

From his desk at NID’s headquarters in Room 39 of the Admiralty, Fleming gained an insider’s view of the war’s events. He was soon taking full advantage of it. In June 1940, on the eve of the French surrender to the Germans, he became the point man in trying to persuade French Admiral Jean François Darlan not to allow the French fleet to fall into German hands. Fleming traveled to France with a radio operator in a vain effort to catch up with Darlan.

Instead, Fleming received NID orders to help British officials and other refugees to escape through Bordeaux, virtually their last opportunity to get out of France ahead of the advancing Germans. He was also able to prevent the Germans from capturing a store of airplane engines and spare parts. He succeeded in getting the large crates aboard a ship that took them to Britain.

Fleming then turned his attention to the masses of refugees seeking a way out of France. Out in the estuary were seven merchant ships at anchor. He borrowed a motorboat, traveled among the ships, and told their captains, “If you don’t take these people on board and transport them to England, I can promise you that if the Germans don’t sink you the Royal Navy will.” The captains complied. One of the refugees so rescued was King Zog of Albania. Realizing there was nothing more he could do about Darlan and the French warships, Ian joined the exodus.

An Ambitious Planner

Back home, Fleming tackled a serious problem posed by the British codebreakers at Bletchley Park. Alan Turing and his colleagues had conquered the Enigma code machines used by the German Army and the Luftwaffe, but the Navy’s adaptation of the Enigma was defying them. They badly needed to capture one of the German naval Enigma machines. Fleming came up with a daring idea. To pick up Luftwaffe pilots downed in the English Channel, the Germans relied on an Enigma-equipped rescue boat. Fleming proposed using a captured German bomber, manned by an English flight crew in German uniforms, to join a flight of German bombers returning from a raid. Over the Channel, their bomber would begin to emit fake smoke. The crew would send out an SOS, ditch the plane, and float in a rubber dinghy until the rescue boat arrived. “Once aboard,” his plan stated, “shoot German crew, dump overboard, bring back boat to English port.”

The plan would require a “word-perfect German speaker.” Fleming saw himself assuming that role, but Godfrey turned him down. Fleming knew too many secrets to be allowed the possibility of German capture. Even though the arrangements had been made, the project was abandoned, much to the disappointment of all involved, when the right situation never turned up.

Building the OSS

When the United States entered the war, Godfrey and his team were dismayed to realize the fractured state of American intelligence. Each service, plus the U.S. State Department and the FBI, had its own intelligence organization, with each zealously guarding its own turf. What was needed, the British saw, was an overall integrated organization such as the one that Godfrey directed. They even knew whom they wanted to be the head of the new organization, lawyer William J. “Wild Bill” Donovan, whose background included intelligence work for his client, the banker J.P. Morgan. In May, Godfrey and Fleming traveled to the United States to see what could be done.

Their first stop was in New York City to consult with William S. Stephenson, head of British Passport Control, which was, in actuality, Britain’s intelligence center in the United States. Stephenson, they found, already had the program for creating Donovan’s operation well advanced. What was needed was a final push to persuade President Franklin D. Roosevelt to endorse it. Godfrey succeeded in inducing Eleanor Roosevelt to invite him to a White House dinner with the president. Roosevelt listened to Godfrey’s request and, shortly afterward, established what became the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) under Donovan, whom he made a major general. The OSS proved to be the forerunner of the modern Central Intelligence Agency (CIA).

Fleming’s part in this triumph was to work with Donovan in drafting the charter for this new department of the U.S. government. As a token of his appreciation, Donovan gave him a revolver inscribed with the legend “For Special Services.” It remained one of Ian’s most prized possessions.

No. 30 Assault Unit

Adding to the incredible range of activities in which Ian was involved during wartime was the key role he played in establishing the propaganda and deception radio broadcasts aimed at the Germans. One type of these broadcasts was labeled white, the other black. White referred to the BBC’s German Services programming designed to attract and mislead German listeners. The black propaganda operation consisted of clandestine media whose purpose was to confound and confuse the enemy. Ian and the NID supplied much of the damaging information aired by these stations and, speaking in his word-perfect German, he made frequent appearances on the broadcasts. In addition, he helped organize two counterfeit stations specializing in misinformation calculated to break the morale of U-boat crews.

In May 1940, observing the British disaster in Crete when the Germans invaded and captured the island, Ian’s attention was drawn to the unusual operation led by Nazi SS commando leader Major Otto Skorzeny. Skorzeny’s unit had landed with the first wave of German invaders, but instead of joining in the combat it had made a dash to the British headquarters. Skorzeny’s soldiers seized all the secret materials they could get their hands on, from codebooks to military maps. This was the sort of intelligence commando tactic, Fleming decided, that the NID should copy. Very quickly he organized the NID’s own equivalent. It was known officially as the No. 30 Assault Unit, or 30AU, but for Fleming they were his marauding “Red Indians.” He recruited and trained what was, in effect, his own small, private army.

Fleming opposed the Allied raid on Dieppe, but when it went ahead anyway he organized a contingent of his Red Indians to carry out a ransacking of German headquarters. The attempt failed when the overall landing proved to be a bloody disaster, and his unit never even got ashore. It was a different story when the Allies invaded North Africa in 1942. His unit of special agents landed near Algiers, surprised the Italian headquarters, and came away with a bountiful harvest that included the current Italian and German ciphers. As the fighting in North Africa continued, Fleming enlarged his army, added a group of protecting Royal Marines, and had them search out other intelligence documents as the enemy retreated. Their prize capture was a map of the minefields and defenses of the coast of Sicily, an invaluable aid to the Allies’ subsequent invasion of that island.

When D-Day, the invasion of Normandy, came, 30AU was trained and ready—this time not just to capture a few maps and codebooks. The unit’s initial task was to plunder a large German radio station before the Nazis could destroy it. When that was accomplished, Ian had a long list of further objectives, particularly the seizure of German secret weapons. Following his instructions as the Allies drove the Germans in retreat, 30AU tracked down the latest German acoustic homing torpedo, an experimental one-man submarine, their latest pattern of magnetic mines, fast submarines propelled by hydrogen peroxide, and additional finds of advanced radar equipment.

The unit’s final coup came as the war in Europe was ending. In Room 39, Ian had been picking up reports about truckloads of German documents converging on a castle in Württemberg. Accompanying his team there, he found that an old German admiral had collected the entire German naval archives dating back to 1870. The admiral was preparing to burn the entire collection rather than let the advancing Red Army seize it. Fleming and the admiral got on well together, with the result that not only the archives but the admiral himself were conveyed to England, where the admiral spent months editing the documents.

Trident, Tehran, and Goldeneye

In his intelligence capacity, Fleming became a regular participant in the international conferences scheduled by British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and President Roosevelt. In May 1942, he was in Washington, D.C., for the Trident Conference, which, among other agreements, fixed the date for the Normandy invasion. In August, he attended the follow-up planning session, the Quadrant Conference in Quebec. In November, he was in Cairo helping to plan for the summit meeting of Churchill and Roosevelt with Soviet Premier Josef Stalin in Tehran. A serious bout of bronchitis kept him in Cairo instead of journeying to the conference.

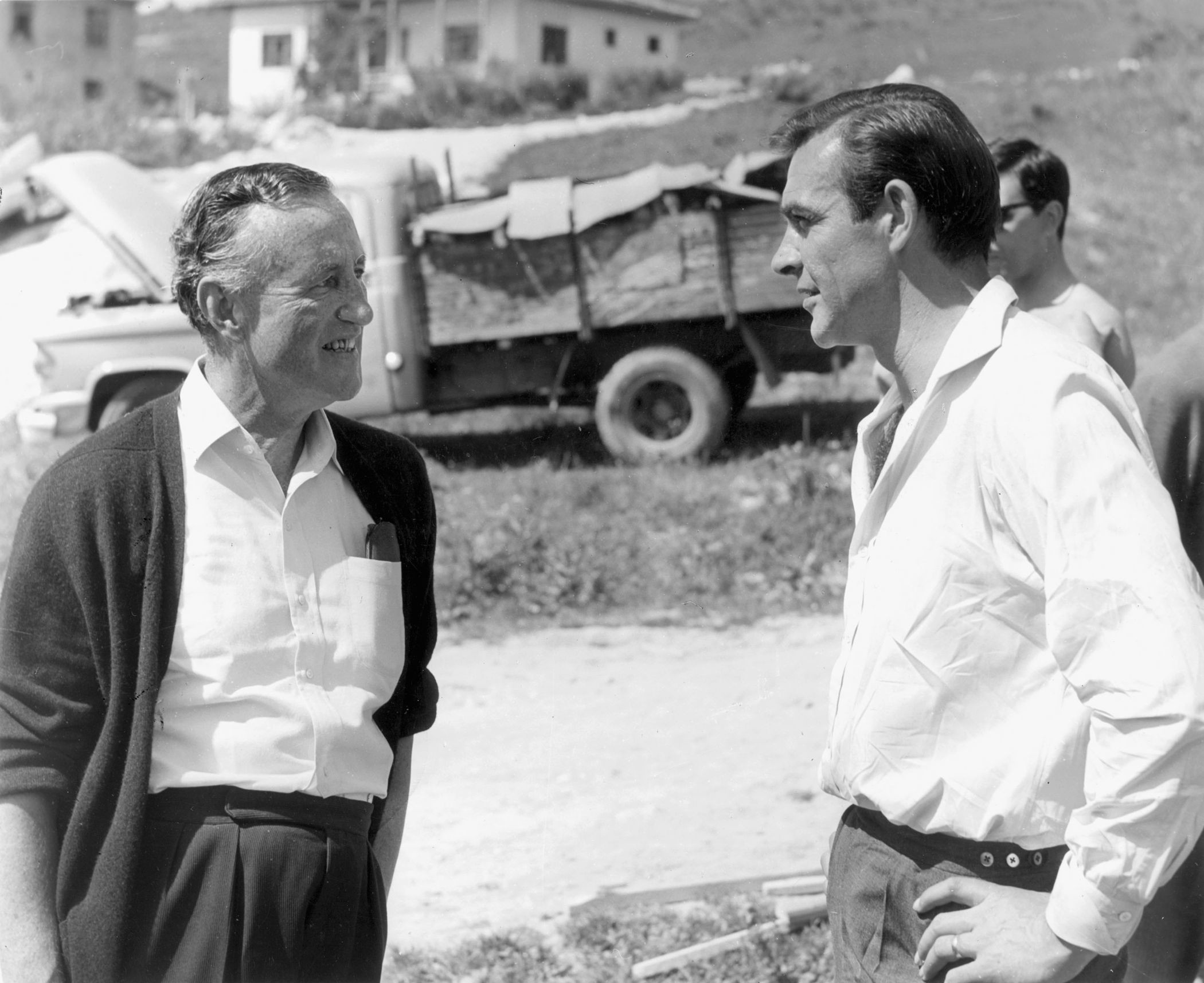

Recalling his experiences with Fleming during their wartime relationship, Admiral Godfrey said, “Ian should have been DNI and I his naval adviser.”

Late in 1944, Fleming went to Washington for a meeting with the U.S. Navy’s intelligence department and then on to a conference in Kingston, Jamaica, dealing with the German U-boat menace in the Caribbean. Before leaving Washington, he renewed his friendship with his old Etonian colleague Ivar Bryce, who was now married to a rich American woman. Ian persuaded Bryce to accompany him to the Jamaica conference. It turned out to be a grueling experience, with a heavy workload made heavier by incessant rain. Bryce owned a home on the Jamaican coast, and by the time the pair arrived there, he was sure Fleming had had a miserable time in Jamaica. Yet, during the flight back to Washington, Ian surprised his friend by announcing that he wanted to buy land in Jamaica and build a house there. Fleming’s decision resulted in his ownership of a beach house he named “Goldeneye.” He had participated in a wartime mission with that codename and spent quite a bit of time at the house for the remainder of his life.

Goldeneye allowed Fleming to avoid the worst of Britain’s winters. The now wealthy Bryce also helped him escape British summers. Bryce’s wife owned Black Hole Hollow Farm in the foothills of Vermont’s Green Mountains near the New York border. Ian became a regular summer visitor. The setting for part of his novel Diamonds Are Forever is in the nearby resort town of Saratoga, New York.

Ian Fleming: The Writer

By the war’s end, Fleming had accumulated a vast store of ideas, impressions, and incidents he was to use in his James Bond novels. As an example, on the trip he and Godfrey made to the United States in 1941, they stopped off en route in Estoril, Portugal. Ian was immediately attracted to the casino. He had not been able to indulge his gambling fervor recently because of Britain’s wartime ban. He played against some Portuguese businessmen and lost. As he was leaving the tables, though, he said to Godfrey, “What if those had been German secret service agents, and suppose we had cleaned them out of their money; now that would have been exciting.” That was exactly the plot for his first James Bond thriller, Casino Royale, requiring only that he change the Nazis into the novel’s villain, an agent for the Soviet Union.

The writing of that first novel, however, was a long time in coming. It was only when he was 43 and nearing marriage with his longtime mistress, Ann Rothermere, whom he had gotten pregnant, that he began writing the book that had been rattling around in his head for years. It was also at her urging that the work began in earnest. At Goldeneye, he began the novel on January 15, 1952, and, working only from 9 am to noon each day, finished it on March 18.

Although Fleming wrote with great speed, he was meticulous and tireless in his research for each book. He traveled to his chosen settings, sought the advice and assistance of experts, raised questions by the thousands, and filled notebooks with the information he would put to use during his next visit to Goldeneye, each of which usually lasted for two months. Early on, when asked whether he himself was the model for James Bond, he scornfully rejected the idea, pronouncing Bond “that cardboard booby.” Gradually, though, he infused himself into Bond’s personality, making his creation more well rounded and human, capable of knowing fear and of crying out when in pain. Of his novels, it must be said that he excelled in seeking out subject matter, such as high-stakes gambling, that was new and fascinating to masses of readers.

During his relatively short life, Ian Fleming experienced only the beginnings of what became a tremendous James Bond industry. Even so, he had seen some 40 million copies of his books sold and had viewed the first James Bond movies before heart troubles felled him in August 1964, at the age of 56.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments