By Pat McTaggart

The great city of Leningrad was being strangled, its people dying by the thousands.

Death came in many ways. German troops under Field Marshal Wilhelm Ritter von Leeb’s Army Group North had been blockading the city since the first week of September 1941. Starvation had already taken its toll as rations were cut for the civilian population, with the very young and very old facing agonizing deaths. There was also the German artillery and the Luftwaffe, which pummeled the city on a daily basis. For those caught in the open, death came quickly if one were lucky.

Orders for the blockade came directly from Adolf Hitler. He did not want his forces to become embroiled in a vast urban battle, which would be both time consuming and costly. However, the city was not entirely cut off. Supplies were still coming in on a haphazard basis on a rail line that ran from Tikhvin through the city of Volkhov, ending at the town of Lednevo located on the shore of Lake Ladoga. From there, supplies were loaded on ships which then made the hazardous trip to Leningrad.

To totally cut off the city, Hitler planned to send his forces across the Volkhov River. Once that was accomplished, General Rudolf Schmidt’s XXXIX Motorized Corps would move north to take Tivkhin with two panzer and two motorized divisions that were supported by infantry. Once Tikhvin was taken and reinforcements arrived, the Germans would continue north to the Svir River and link up with Finnish units of the Karelia Army, effectively cutting all lines of supply to Leningrad from the outside world.

The Spanish Blue Division

Schmidt’s southern flank would be protected by infantry units, one of which was the 250th “Azul” (Blue) Division, made up entirely of Spanish volunteers. The Blue Division was Spanish leader Francisco Franco’s contribution to the war against the Soviet Union. Hitler had tried to persuade Franco to become an Axis partner in 1940, but the wily Spanish dictator asked for supplies and war matérial that Germany could not possibly provide before he gave his approval. Hedging his bets, Franco remained neutral during the war, but he did authorize raising a division of volunteers to participate in the “war against Bolshevism.” The gesture was also partial repayment for the help received from Germany during the Spanish Civil War. It would also give Franco the appearance of giving Hitler help in the war in case Germany was victorious in the East.

While Schmidt’s motorized corps was assembling for the attack on Tikhvin, the Blue Division marched toward Veliky Novgorod located on the north shore of Lake Ilmen. There, it became part of Group von Roques, commanded by General Franz von Roques, the rear area commander of Army Group North. Roques was tasked with crossing the Volkhov River on a front running from Novgorod north to Chudovo—a front of about 84 kilometers.

The purpose of the attack was threefold. Besides providing for Schmidt’s flank, an attack across the Volkhov in that sector would draw enemy troops to the area, which would hopefully make Schmidt’s task easier. Bridgeheads established on the eastern riverbank could also be used as springboards for future offensive operations.

Major General Augustin Muñoz Grandes, commander of the Blue Division, received his orders from Roques. The Spaniards were to cross the Little Volkhov River north of Novgorod, drawing the attention of the Soviets. Meanwhile, Maj. Gen. Paul Laux’s 126th Infantry Division would cross about 45 kilometers to the north at Kuzino. Once both divisions secured bridgeheads on the eastern bank, they would assault Soviet positions of the Valdai Hills.

Assault Across the Volkhov

On October 16 the offensive opened with artillery fire raining down on the Soviet positions opposite the Spaniards. The Soviets responded in kind and also called for reinforcements, thinking that the entire sector would become the object of a major attack. Meanwhile, the 126th crossed at Kuzino while the Blue Division remained in place, keeping the Russians guessing where the attack would occur. To the north, shielded by General Kuno-Hans von Both’s I Army Corps, Schmidt moved forward in his thrust toward Tikhvin.

Muñoz Grandes was finally ordered to move forward on October 18. During the next few days, despite pouring rain and an insufficient number of boats, the Blue Division established bridgeheads on the eastern bank of the Volkhov. The bridgeheads were attacked by Brigade Commander Iakov Dmitrievich Zelenkov’s 267th Rifle Division, but the Spaniards held their perimeter while ferrying more men across the river. Finally linking up with the 126th, Muñoz Grandes and Laux proceeded to advance. The terrain favored the defenders. Pocked with woods and swamps that restricted movement, the Russians had set up defensive positions along anticipated avenues of advance. Reinforcements from the 305th Rifle Division and 3rd Tank Division were also arriving in the area.

Northwest of Tikhvin, I Army Corps infantry units advanced on the city of Volkhov. Besides guarding Schmidt’s left flank, the initial thrust was to be made up the western bank of the Volkhov River north of Kirishi. Maj. Gen. Herbert von Böckmann’s 11th Infantry Division took the lead and soon ran into Soviet defenses that slowed his advance to a crawl.

Reinforced with part of Maj. Gen. Otto Sponheimer’s 21st Infantry Division, Böckmann (whose command was now called Group von Böckmann) continued to attack through the Maluksinskii swamp. The area was defended by the 285th, 310th, and 311th Rifle Divisions of Lt. Gen. Vsevolod Fedorovich Iakovlev’s 4th Army, which were dug in and determined to stop the German advance. Because there were only a few good avenues of advance, defenses were prepared in depth. The history of the 21st Infantry describes part of the advance of Group von Böckmann as it prepared to cross one of the tributaries that fed the Volkhov.

“The enemy was probably aware, admittedly, of the importance of this river area. Outside a village [Red Army] units counterattacked the regiment, which was advancing from the direction of Lyubuny. The regiment repulsed the attacks and then, in a counter thrust, stormed the village and prepared to break through the enemy positions on the river.” Such actions continued to slow the advance.

Costly Russian Counterattacks

The Soviets showed great tenacity all along the Volkhov. Although mistakes were initially made in Red Army troop dispositions, they were countered by the weather and the terrain across the entire region. While Groups von Roques and von Böckmann slogged forward, Schmidt’s forces were also facing increasing resistance. Freezing weather followed by periods of thaw turned the primitive roads in the Tikhvin area into an endless mass of mud.

As Schmidt moved his motorized forces closer to the town, Stavka (the Soviet High Command) sent reinforcements to Iakovlev’s 4th and Lt. Gen. Nikolai Kuzmich Klykov’s 52nd Armies. Those forces continued to grind down Schmidt’s divisions as they occupied new defensive positions. They also mounted counterattacks against Schmidt and his flanking infantry divisions. Although costly and poorly coordinated, they had the desired effect of further slowing the German advance.

Farther south the troops of Group von Roques faced similar problems. To the men of the Blue Division, their attacks seemed like anything but a diversion as soldiers of the 305th Rifle Division hit a section of the front with two battalions supported by artillery and heavy mortar fire. The assault centered on the small village of Nikltkino. The Spaniards held their ground, machine-gun fire spitting out a stream of death toward the advancing Soviets. A Spanish machine gunner, Tomãs Salvador, was amazed at the way the Russians advanced, never seeking cover or crouching down unless ordered to. When the fighting was over the Spaniards counted 221 dead Russians in front of their position. Their own casualties were 15 dead and 50 wounded.

“More Casualties From Cold Than From Enemy Fire”

On November 6, an Arctic blast hit the Volkhov area. Rivers and streams began to freeze and snow began to fall. The weather proved to be both a blessing and a curse for the Germans. With muddy roads freezing solid, the motorized drive toward Tikhvin could continue. Schmidt captured the town on November 8, advancing through a heavy snowstorm, but that was as far as he got. The ravages of combat, increased Soviet resistance, and the onslaught of winter made any further advance to the Svir River impossible.

Soviet forces suffered along with their German counterparts as the cold set upon them. Frostbite was rampant on both sides, and winter clothing was in short supply. On the Soviet side, the vast bureaucracy resulted in massive delays of vitally needed supplies. Padded jackets, fur gloves, and warm hats lay rotting in forgotten depot areas because of gross inefficiency. New winter uniforms were issued to divisions that were forming, but few found their way to the frontline troops.

However, it does appear that the average Red Army soldier was a little more innovative than his German counterpart during that first savage winter of the war. Paper and straw were stuffed into boots and under uniforms to provide extra protection from the sub-zero temperatures. The Russians also had the “luxury” of holding defensive positions, which provided some shelter from the elements, while the attacking Germans were forced to keep moving in the open.

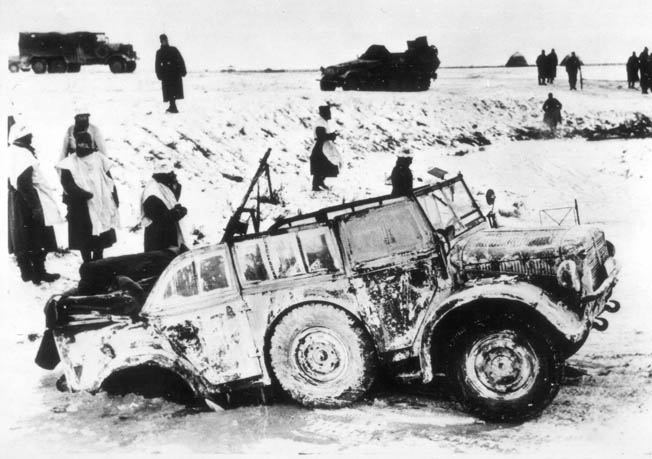

For the Germans, the incredible cold caught them flat-footed. There was no winter clothing to be found, and the summer uniforms that carried a victorious Wehrmacht into battle in June had become worn and threadbare. Troops wore all the clothing they carried, which also made movement more sluggish. The leather boots that the average soldier wore were no match for the Russian winter, and they also served as conductors of the cold, which caused even more frostbite.

After the war, General Erhard Raus, a highly decorated panzer commander, wrote about the effects of that first winter: “When German troops were attacking Tikhvin in the winter of 41, cold set in suddenly. Lacking winter clothing and adequate shelter, the Germans suffered more casualties from cold than from enemy fire….”

“A Very Bad Turn”

On the same day Schmidt’s forces entered the town, Group von Böckmann, now reinforced with Maj. Gen. Walter Behschnitt’s 254th Infantry Division, was nearing the southern outskirts of Volkhov. The advance was stopped by Soviet counterattacks, but it was worrisome enough for Stavka to relieve Iakovlev and replace him with General Kiril Afansevich Meretskov.

By mid-November, the Germans were facing the reality of their situation. As losses mounted and temperatures plummeted, even Berlin recognized that nothing more could be gained by continuing the expansion of the bridgeheads across the Volkhov. Supplies were running short, and the troops manning the 350-kilometer front on the eastern side of the river were stretched dangerously thin.

In the November 16 entry of his diary, General Franz Halder, chief of staff of the Army, wrote: “The situation between Lake Ladoga and Lake Ilmen has taken a very bad turn … 21st Division thinks it can get as far as Volkhovstroi [Volkhov Station], but it will not be able to advance farther unless it receives reinforcements … Commander of the Army Group [von Leeb] has considered abandoning Tikhvin in favor of strengthening the ‘Volkhov Front.”

Von Leeb had good cause to worry. Since November 12, Soviet forces had been attacking all along the Volkhov River front with forces from Meretskov’s 4th Army, Klykov’s 52nd Army, and Maj. Gen. Ivan Ivanovich Fediuninskii’s 54th Army. The attacks were meant to retake Tikhvin, keep pressure on the rest of the front, and prevent movement of forces to support Army Group Center’s drive on Moscow, which was making some progress.

In the north, Fediuninskii’s divisions probed the lines of Group von Böckmann, while Meretskov continued to pound at the forward German units at Tikhvin. Farther south, Klykov’s 111th, 259th, and 267th Rifle Divisions attacked the 126th Infantry Division’s strongpoints on the eastern bank of the Volkhov at Malaya Vishera, Bolskaya Vishera, Glutno, Muasnoy Bor, and Krasnaya Viherka.

The Blue Division was hit by the 305th Rifle and 3rd Tank Divisions. A part of the division was surrounded around the town of Posad, and other strongpoints were also in danger of being surrounded or overrun. With no way to extricate the wounded in the threatened areas, many of them froze to death as temperatures continued to plummet.

Meanwhile, the divisions of Group von Roques were taken over by General Friedrich-Wilhelm von Chappius’s XXXVIII Army Corps. The dismal results of von Roques’s advance since the Volkhov had been crossed had caused his dismissal, but as Chappius looked at the dispositions of the units on the eastern bank he could see that the attack had been bound to fail, given the terrain and the strength of the enemy.

Shortly after Chappius took over the sector, units of Colonel Afansii Vasilevich Lapshov’s 259th and Colonel Sergeii Vasilevich Roginskii’s 111th Rifle Divisions overran German outposts and struck the rear of Laux’s 126th. They succeeded in capturing Malaya Vishera, which forced Laux to order a general retreat along his section of the line.

Although the 126th was in retreat, it was no rout. In the sub-zero temperatures the soldiers from the Rhineland and Westphalia prevented the Soviets from making a full breakthrough to the Volkhov. During the fighting withdrawal, Laux’s men held on until being reinforced by Maj. Gen. Baptist Kniess’s 215th Infantry Division, which had recently arrived from France.

The First Soviet Counteroffensive

The Soviet attacks along the Volkhov in late November were the first real Russian counteroffensive of the war. In the central and southern sections of the Eastern Front, German forces were still struggling to maintain the offensive, but the defense of the eastern bank of the Volkhov and the counterattacks on that front had stopped the Germans cold. Although the Germans had been forced to go on the defensive in local areas in the past, for the first time in the Eastern campaign an entire German army had lost the initiative and had been forced to adopt a defensive posture. Although it was on a limited front, the mere fact that this had happened gave the Soviets a big boost in morale.

The November offensive was only a part of the overall plan that Stavka had prepared for a more general counteroffensive across the entire Eastern Front. Buoyed by the knowledge that the Japanese would not attack the Soviet Union, Stalin moved division after division from his Far Eastern Army westward. New divisions had also been raised quickly—as events were to show too quickly—and reinforcements were being fed into frontline units that had been bled white by the previous months’ fighting. Saving Moscow would be the main priority, but raising the Leningrad siege was also an important objective in the northern part of the front.

The final days of November saw fresh attacks by the Soviets along the Volkhov. The 54th Army had taken the initiative after stopping units of Both’s I Army Corps six kilometers south of the city of Volkhov. Feduiuninskii’s army, now reinforced with the 80th Rifle Division from the Leningrad Front, continued the assault and forced Sponheimer’s 21st Infanrty Division to retreat several kilometers.

On the eastern bank of the Volkhov, attacks against the 126th Infantry Division threatened the river crossing at Chudovo. The 126th, after its fighting withdrawal, was almost at its breaking point with some companies at no more than platoon strength. Laux exhorted his men to hold on, knowing the importance of holding Chudovo and denying the enemy the area.

It was the same for Muñoz Grandes’s Blue Division, which held a front of 110 kilometers. Posad still held—a small corridor having been opened to provide contact with the rest of the division. The Spanish had been under intermittent attack for several days, which further depleted their units. Although freezing in their foxholes and trenches, the men refused to give way. To them it was a matter of national honor to keep the Soviets from reaching the Volkhov.

Their corps commander, Chappius, was not so sure. He had not been particularly impressed while visiting the division, noting its poor equipment (supplied by the Germans) and understrength artillery (also supplied by the Germans). “I don’t believe the Spanish can hold Novgorod against a strong Russian attack,” he told 16th Army commander General Ernst Busch. “With the loss of Novgorod, the Reds will win a prestigious prize.”

Busch, who had been in contact with Muñoz Grandes since the Blue Division had entered his sector, let a few seconds go by. “The commander of the Spanish Division told me … that, especially on the Novgorod Front, he will be able to hold his positions,” he replied. With that, the conversation ended.

Soviet Propaganda in Castilian

During the first days of December, all eyes were on the German attempt to take Moscow. German forces had clawed their way to within sight of the spires of the Kremlin, but they could go no further. The Moscow defensive ring had held, and the time was right for Stalin’s counteroffensive, which he entrusted to General Georgii Konstantinovich Zhukov.

Along the Volkhov, Meretskov’s 4th Army was hammering away at the German forces around Tikhvin, while Fediuninskii and Klykov continued to attack the left and right flanks guarding Schmidt’s precarious positions. Fortunately, those attacks were ill coordinated, usually resulting in heavy Soviet losses due to their reliance on frontal attacks. It seemed that the lines would hold, even though German ranks were also thinning at an alarming rate. All that was about to change on December 5.

An incredible cold front moved through the area, dropping temperatures to below minus 30 degrees Fahrenheit. In their threadbare summer uniforms, German soldiers literally froze to death at their posts. It was the perfect moment for the Soviets to attack. The Russian counterattack at Moscow began, and German forces reeled from the assault. Hitler reluctantly called off his Moscow offensive, instructing units all along the front to assume a defensive posture.

On the Volkhov, December 5 saw a renewed effort by the 4th Army to take Tikhvin. To the south, the 126th and Blue Divisions struggled to repulse Soviet attacks on their positions. Heavy artillery fire pounded the garrison at Posad, which was once again surrounded. Between barrages, Soviet propagandists, speaking perfect Castilian, tried to persuade the Spanish to surrender.

“We admire your resistance as heroic, as it is useless,” the loudspeakers blared. “Don’t you know you are surrounded? Kill your officers and join us, we will respect your rank. To our rear are beautiful cities, entertainment, diversions … you will no longer be cold.”

The Spaniards answered with catcalls and curses. They soon faced a renewed infantry assault supported by light tanks. After heavy fighting the Russians withdrew, leaving a mass of bodies in front of the Spanish positions. Then, the loudspeakers began once more.

My Soldiers Will Fight to the Death

On the Blue Division’s left flank, Laux’s 126th was hit along its front by up to five divisions. The strongpoint at Nekrasovo, about 18 kilometers east of the Volkhov, was lost, giving the Russians access to one of the few good roads in the area. With its capture, the entire line on the eastern bank was in jeopardy. Conferring with Busch after learning of the loss, Chappius proposed a complete withdrawal to the western bank of the river, with Muñoz Grandes holding the Novgorod sector and Laux defending the area around Chudovo.

During the next few days the Blue Division pulled back step by step. The four companies at Posad broke through the encircling Russians, taking what wounded they could with them. Once across the Volkhov the Spaniards occupied makeshift defensive positions. The men were exhausted, and some battalions were down to between 200 and 250 men.

Chappius was concerned about the reliability of the Blue Division after speaking to Muñoz Grandes. He asked the Spanish general if his men could hold the line. Muñoz Grandes replied that, with the shape his men were in, it was doubtful they could do so for long.

“Then I shall recommend that you be pulled out for rest and resupply in a safe area behind the front,” Chappius said.

That was deemed a personal insult, not only to Muñoz Grandes, but also to his men—both living and dead. He glared back at his corps commander and answered, “We will recuperate in the line. My soldiers will fight to the death.”

The German Retreat

German divisions along the Volkhov were in no better shape than the Blue Division. Most of the horses that the infantry divisions depended on to transport artillery and supplies were dead. Entire units had ceased to exist, and the bitter cold continued to drain more and more men.

In the Tikhvin sector, Meretskov continued to squeeze the German forces defending the corridor leading to the town, and by December 7 forward Soviet units were in Tikhvin’s outskirts. Enveloped on three sides, it was only a matter of time before the Russians would retake their prize.

Hitler bowed to the inevitable on December 8 and allowed Schmidt to retreat from the town. Two days later Tikhvin was back in Russian hands after overcoming a desperate German rearguard action. In the meantime, Schmidt’s troops were now on their way back to the Volkhov, hoping to form a defensive line on the western bank.

Smelling blood, the Russians tried to turn the retreat into a rout. Schmidt’s forces were in terrible shape—his two panzer divisions down to about 30 tanks each. Brig. Gen. Friedrich Herrlein’s 18th Motorized Division had only 741 men fit for combat, and the flanking infantry divisions were equally decimated.

For once, the terrain favored the Germans. Units at the front of the retreating columns set up defensive positions at key points, allowing the rest of the men through before retreating to the next position, which was already occupied by the next unit in line. The Soviets, also hindered by the snow that had fallen, threw themselves at the German positions, but the German leapfrog tactics made it impossible for the Russians to score a clean victory.

Meretsov Digs in on the Volkhov Line

Both’s I Army Corps was also fighting for its life. Soviet ski units were constantly harassing its flanks and making penetrations into the rear areas, attacking supply columns and cutting lines of communication. The main objective for the Russian forces was Kirishi. Taking the town would give the Soviets a staging area for cross-river assaults.

On December 17, Stavka formed the Volkhov Front, which would have command control over the area. Meretskov was appointed its commander and Maj. Gen. Petr Alekseevich Ivanov replaced him as 4th Army commander. The front was also to be reinforced with two newly formed armies, Lt. Gen. Grigorii Grigorevich Sokolov’s 26th and Maj. Gen. Ivan Vasilevich Galanin’s 59th.

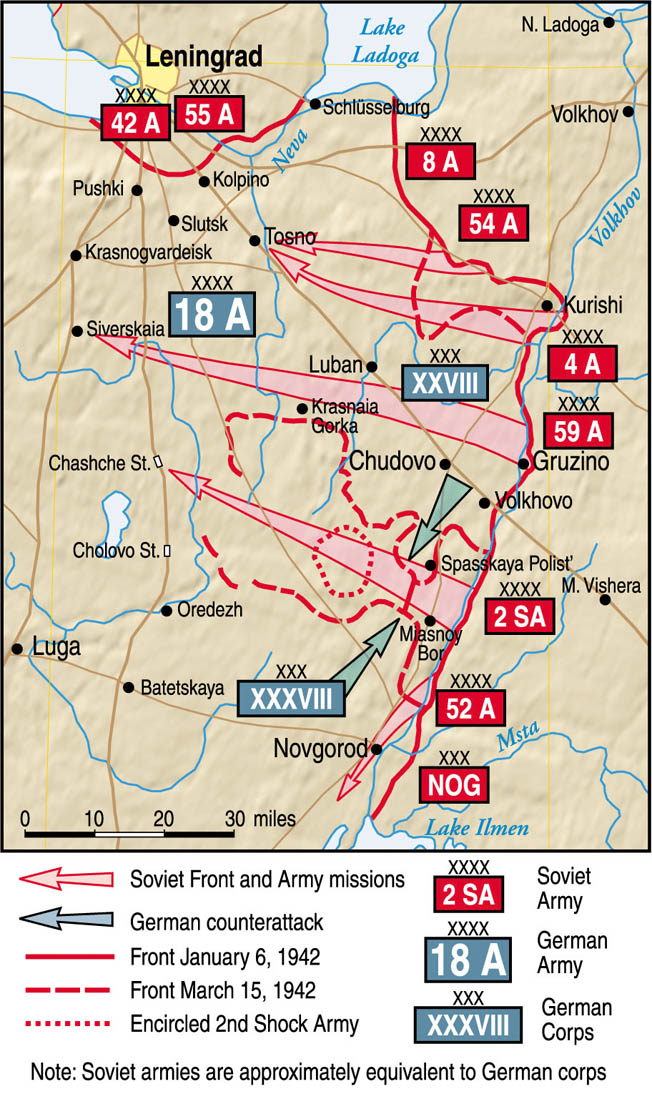

While the Germans were struggling to make their way back to the Volkhov, Stavka devised a fresh mission for Meretskov’s command. The front was to cross the Volkhov and make a thrust toward Lyuban, about 33 kilometers west of the river. Expanding his bridgehead, Meretskov was then to attack northwest to encircle German forces along the Neva River line and link up with attacking forces from the Leningrad Front. There was one problem. Soviet forces were still several kilometers away from the Volkhov in the planned area of the attack.

Even with his two new armies, Meretskov found it impossible to accomplish the task set before him. Most of his men were as exhausted as the Germans. Huge quantities of supplies and ammunition had been expended in forcing the enemy back to the Volkhov, and the cumbersome Soviet bureaucracy was still having problems getting material to the fighting front in a timely manner. As Russian units made their way to the eastern bank of the river, they were hampered by continuing heavy snowfalls, which made the going even slower.

Stavka finally realized that the plans for a December crossing of the river were no longer feasible, and as troops trickled into the Volkhov line they, like their German counterparts, dug in to rest and await more supplies. It was a respite that both sides needed. For the men at the front, the cold was a mutual enemy, and dugouts along the front line provided some relief from temperatures that had now reached minus 40 degrees Fahrenheit.

Stavka’s Flawed Timetable

The Soviet victory at the gates of Moscow along with other successes along the Eastern Front had made Stalin more ambitious. Besides keeping the pressure on the Germans west of Moscow, he had Stavka draw up meticulous plans for an overall general offensive from Leningrad to the Black Sea. On January 1, Soviet forces hit the Germans in the Ukraine. This was followed by a series of staggered attacks along the rest of the front.

For Soviet units on the Volkhov, the offensive began January 4 with Fediuninskii’s 54th Army hitting German forces east of Kirishi. The attack was poorly coordinated. Because of the strict timetable set by Stavka for the attack, some units had not yet arrived at their jump-off points while others had not been fully concentrated at the main points of the assault. As a result, the Soviets were only able to advance four or five kilometers. The two divisions facing Fediuninskii’s forces, the 11th and 126th, held their ground and inflicted heavy losses on their attackers. Elements of Brig. Gen. Josef Harpe’s 12th Panzer Division were rushed to the area, and the attack disintegrated. After two days of fighting, the 54th was forced back to its starting positions.

Still under Stavka’s timetable, Meretskov ordered his other armies to attack on January 6, despite Fediuninskii’s failure. The plan called for Galinin’s 59th Army to batter its way across the Volkhov in the Gruzino area. After expanding its bridgehead, Sokolov’s army, which had been renamed the 2nd Shock Army in late December, would follow. The two armies would then make a thrust toward Lyuban while enlarging their flanks to the north and south and meet up with attacking forces from the Leningrad Front. Meanwhile, Klykov’s 52nd Army was to cross the Volkhov and destroy enemy forces around Novgorod. Ivanov’s 4th Army would cross the river on Meretskov’s right flank to protect the drive to Lyuban.

Coordination of these attacks would be a struggle for the staffs of these armies, even if Meretskov had been given a month or two to carefully plan the offensive. Given the short timeline issued by Stavka, it was a logistical nightmare. Fuel and ammunition were still making their way to the front, and the few good roads in the area were filled with massive traffic jams, with units becoming intermingled as they struggled to reach their jump-off points.

Bridge Crossings With Heavy Casualties

Nevertheless, Meretskov opened his offensive on January 6 with a preliminary artillery bombardment that was hampered by a lack of shells. It was, however, enough to keep the Germans’ heads down as the first wave of Galanin’s army moved across the Volkhov. The river was 400 meters wide in some spots, and the advancing Russians found themselves exposed to enemy fire as the Germans recovered from the barrage.

Reaching the western bank, the survivors of the first wave laid down covering fire for the following troops. German artillery then started to hit the bridgehead and casualties mounted, but the Russians kept coming. Local German counterattacks forced some Soviet units back across the river, but enough of the following wave made it across to firm up and expand the bridgehead.

By the end of the day, the 8th Rifle Division was entrenched in the Vodos’ia sector while the 376th and Colonel Ivan Mikhailovich Platov’s 288th Rifle Divisions moved forward to the Menesksha River. Colonel Sergii Vasilevich Roginskii’s 111th Rifle Division was struggling against German strongpoints at the mouth of the Lyuban’ka River, and elements of the 372nd Rifle Division had established positions south of Krasnofarfornyy on the west bank of the Volkhov south of Gruzino. It was not the smashing success that Stavka had envisioned, but it was a start.

Although the 2nd Shock Army’s artillery was still in transit and some of its units had not yet arrived, Meretskov threw the remaining troops of the 59th Army into the fray. He also ordered the 2nd Shock Army to move into the bridgehead the following day. Once across the river the troops were immediately involved in a series of uncoordinated attacks against German positions.

The Germans were ready, and they met the Soviets with a wall of fire. Sokolov, a former NKVD (secret police) commander, was completely out of his league. His clumsy handling of the initial assaults cost his army more than 3,000 casualties as it attacked without the needed artillery or air support. Frontal assaults against the dug-in Germans cost more casualties in both the 2nd Shock and 59th Armies, resulting in Stavka ordering a halt to operations on January 10 so the two armies could try and consolidate their positions on the west bank.

On the northern flank, Ivanov’s 4th Army found itself the object of counterattacks that caused heavy losses to the 65th Rifle Division and Colonel Ivan Pavlovich Roslyi’s 4th Rifle Division. The counterattacks forced a limited withdrawal before the Russians could stabilize the line. To the south, Klykov also ran into serious trouble while trying to cross the river.

Lev Mekhlis: Stalin’s Commissar on the Volkhov

North of Novgorod, the Soviets had more success. A gap between the 126th and 215th Infantry Divisions had grown to about five kilometers. While the 215th continued to hold its line, the 126th was in danger of collapsing. Colonel Harry Hoppe, commander of Infantry Regiment 424, 126th Infantry Division, was hard pressed to keep the Russians at bay. Soviet forces took the town of Teremets and then moved to expand the bridgehead, threatening the north-south road and railway system from Novgorod to Chudova. Reinforced with troops from the neighboring Blue Division, Hoppe tried to retake the town, but his repeated attacks were repulsed as more Russian units entered the area.

At this point, Stavka ordered another halt to allow Soviet forces to regroup. During the lull, the Soviet command on the Volkhov underwent some important changes. Sokolov was sacked for the incompetent way he had handled his army. He was replaced by Klykov, who turned over the 52nd Army to Iakovlev. A representative from Stalin, Army Commissar 1st Rank (equivalent to General of the Army) Lev Zakharovich Mekhlis, arrived at Meretskov’s headquarters to serve as Stalin’s representative on the Volkhov.

Mekhlis was a close confidant of Stalin. He literally had the power to remove and execute any soldier or commander that he considered not showing the proper fighting spirit. Even though he had no command experience, he would constantly meddle in the military operations on the Volkhov Front. His word was law, and a “suggestion” from him had to be regarded as a direct order from Moscow.

Von Leeb Relieved “For Reasons of Health”

The offensive resumed on the 13th with the 2nd Shock Army making some gains against the German defenders. The Russians might have obtained greater success if they had simply bypassed the hastily erected strongpoints of the 126th. As it was, the inexperienced recruits and local commanders used the frontal assault to try and overrun them. It was a costly and bloody affair, which yielded little result.

At one such strongpoint in the village of Senitsy, 1st Lt. Ernst Klossek, commander of the 12th Company of Infantry Regiment 422, fought off several attacks, denying the Soviets their objective and causing severe casualties among the attackers. His company’s staunch defense of the village earned Klossek the Knight’s Cross.

Looking at the big picture, Army Group North’s commander, Leeb, saw the dangers represented by the offensives of the Volkhov and Leningrad Fronts. His troops were barely hanging on, and he asked Hitler for permission to either retreat to form a more stable line or to relieve him. Hitler had already decided on a “no withdrawal” policy, so von Leeb was relieved “for reasons of health” on the 17th. He was replaced by 18th Army commander Georg von Küchler, who turned his command over to General Georg Lindemann.

Soviets Short on Supplies

The day Leeb was relieved, Meretskov called another halt to his offensive to reinforce the west bank forces and consolidate his line once again. With Klykov’s fresh troops, the offensive resumed on the 21st. Several German strongpoints were taken and the bridgehead was widened somewhat, but the following day Meretskov called for yet another halt as he expressed worry about the 2nd Shock Army’s northern flank where Galanin’s 59th Army was making abysmal progress.

After transferring three infantry divisions and four artillery regiments to beef up Galanin, Meretskov ordered the assault to resume. Exploiting Klykov’s success from a few days ago, Maj. Gen. Nikolai Ivanovich Gusev’s 13th Cavalry Corps (25th and 87th Cavalry Divisions), supported by infantry, broke into the German rear. The Germans reacted by reinforcing the flanks of the penetration, and although Gusev and his accompanying infantry had made good progress, the lack of supplies inside the bridgehead once again forced a halt to offensive operations.

I.I. Yelokhovsii, a platoon commander of a 76mm artillery battalion in Lt. Col. Chernik’s 59th Independent Rifle Brigade, recalled the situation: “It was not only shells that were lacking. The supply situation from January right up to the very end was deplorable. Food was in short supply. Pea soup mash in a common pot for 10 men—that was it. We were saved by the fact that the artillery was horse-drawn. There was no way to feed the horses … they died and we ate them. This occurred around once a week….”

Under continuous prodding from Mekhlis, Meretskov once again resumed his attack. The 2nd Shock Army position resembled a mushroom, with a fairly strong base established along the western bank of the Kolkhoz followed by a narrow stem that expanded into the main section of the salient. It was that narrow stem that threatened Klykov, but try as they might the Soviets could not dislodge the German forces that threatened the corridor.

Meretskov continued to funnel men and supplies across the Volkhov. Getting supplies to the front line was another matter. The swamps and forests hampered the movement of food and ammunition, which had to be brought forward by sleds or horses. The artillery, as Yelekhovskii noted, also faced extreme difficulties in keeping up and supporting attacks.

Nevertheless, at the end of January Meretskov ordered his forces to continue attacking as planned. The 59th and 52nd Armies threw themselves against the narrow corridor at the base of the salient. The 2nd Shock Army was split into three operational groups that were to expand the perimeter of the salient by assaulting German strongpoints on the flanks. Those attacks were to be supported by tanks that had made their way to the front. Meanwhile, Gusev and his supporting infantry would continue to advance on Lyuban.

The Germans Regroup

Meretskov’s stop and go assault had given Küchler time to reorganize his command and move more units around the perimeter of the 2nd Shock Army. By early February, the northern flank was occupied by Maj. Gen. Siegfried Hänicke’s 61st, Maj. Gen. Theodor Ender’s 212th, Maj. Gen. Hans von Basse’s 225th, and Kniess’s 215th Infantry Divisions, as well as SS Brig. Gen. Alfred Wünnenberg’s SS Polizei (Police) Division. The southern flank was held by Maj. Gen. Erich Jaschke’s 20th Motorized and Laux’s 126th Infantry Divisions, reinforced by part of a security division.

Impressive as the German order of battle looked on paper, most of the divisions had been severely weakened by the earlier fighting. With more than 100,000 men inside the salient, Meretskov thought success was possible. He pushed more troops toward Gusev’s position while Klykov’s operational groups hit the Germans on the flanks.

A key defense point was Spasskaya Polist’, held by units of Kniess’s 215th. An operation group under Maj. Gen. Ivan Terentevich Korovnikov attacked the area with three infantry divisions and a tank brigade, but once again poor coordination between the infantry and armored units led to failure. A similar fate befell the Zhilitsov Operation Group at the strongpoint at Zemtitskoye. Both German positions were key to capturing the north-south communication network to Novgorod.

In the south, the 126th was able to hold onto the strongpoint at Podberezye. With help from an artillery battery sent by the Blue Division, the Soviets were beaten back. Around Novgorod, the Spanish line also held against several Soviet attacks.

Advancing Through the Snow

Throughout February, as the Russian units on the flanks of the salient continued to widen the bulge, Gusev’s cavalry and supporting infantry continued to advance toward Lyuban. The commissar of the 59th Independent Rifle Brigade, now led by Colonel I.F. Glazunov, recalled: “During the first days of February, the brigade captured the town of Dubovik … A punitive company of Estonian irregulars was routed and destroyed. Its commander was captured and executed.”

Glazunov’s brigade then advanced farther to the edge of a forest near the villages of Bol’shoe and Maloe Yeglino, where it halted to await the arrival of more units. The villages were heavily defended, but with the help of a couple of ski battalions the 59th took them. However, without cavalry to support a further advance, German positions along a viaduct west of the villages forced the Russians to go into a static mode.

V.N. Sololov, a clerk at the 13th Cavalry Corps Headquarters, recalled the difficulties of the advance. “On February 11 the cavalry reached the town of Dubovik but was unable to advance further through the deep snow and trackless landscape. There was no hay to be had for the horses, as the Germans had swept everything clean, while under the snow was nothing but swamp, void of anything edible. The cavalry could not exploit the successes of the rifle divisions and assumed a defensive posture on foot.”

Stavka’s Plan to Encircle the Germans

The goal of Lyuban was tantalizingly close, but Glusev and his supporting troops had run out of steam. Recognizing an opportunity, the Germans attacked Soviet positions at Krasnaia Gorka, about 15 kilometers southwest of Lyuban, with Maj. Gen. Kurt Herzog’s 291st, Hänicke’s 61st, and Kniess’s 215th Infantry Divisions. Retaking the village on February 28, the Germans then encircled the 80th Cavalry Division, which had been brought forward, and the 327th Rifle Division, which had almost reached the outskirts of Lyuban.

P.I. Sotnik, commissar of the 100th Cavalry Regiment of the neighboring 25th Cavalry Division, recalled the events near Lyuban: “The enemy put up stubborn resistance on the southwestern outskirts of Lyuban, then launched a tank attack, which pushed our forces back to a forest. Our units passed over to the defense…. Supplies of food and artillery shells were nonexistent and the ammunition ran out…The [Soviet] units were forced to destroy all of their heavy equipment and during the night of March 8-9 attempted to break through to the main forces with nothing but sidearms, suffering heavy losses….”

While Gusev’s forces were fighting for their lives, the Germans were formulating a plan to totally cut off the Soviet salient. Reinforced with Brig. Gen. Friedrich Altrichter’s 58th Infantry Division, Chappius’s XXXIII Army Corps (126th and 150th Infantry Divisions) would attack up the rail/highway line north of Novgorod while the 215th and SS Police Divisions would attack southward along the same thoroughfare. When the two forces met, the Volkhov pocket would be sealed.

Meanwhile, Meretskov was still ordering his forces to attack, even though supplies inside the pocket were rapidly dwindling. North of the pocket, Fediuninskii’s 54th Army was still attacking the German forces on his bridgehead perimeter. Reinforced by Maj. Gen. Nikolai Aleksandrovich Gagen’s 4th Guards Rifle Corps, he managed to push forward to within 22 kilometers of Lyuban by March 15. With that success, Stakva put more pressure on Meretskov to keep his own offensive rolling inside the salient with the objective of meeting up with the 54th, which would trap several German divisions.

The Russian command was optimistic that the two forces would be successful in linking up. A March 15 entry in the Leningrad War Diary stated, “The Volkhov Front’s 2nd Shock Army and the Leningrad Front’s 54th Army are conducting offensive operations with the aim of encircling the enemy Lyuban grouping, which can considerably ease the blockade of Leningrad.”

The Raubtier Offensive

Coincidentally, after days of delay waiting for weather good enough for Luftwaffe support to arrive, the Germans opened an offensive code named Raubtier (Bird of Prey) against the 10-kilometer-wide corridor leading into the pocket. In temperatures of minus 20 degrees Fahrenheit, the Germans rolled forward. The order of the day for the 58th Infantry Division read, “We have been given a task which will have a decisive influence on the entire situation in the Leningrad area. Because of the cold and the difficult terrain, it will make extraordinary demands on us!”

The Soviets defended their positions with terrible ferocity. German soldiers waded through waist-deep snow, pushing slowly toward their objectives—two Russian supply routes nicknamed Dora and Erika. In the north, Wünnenberg led his division from the front, funneling his companies into combat in an area west of Spasskaya Polist. In the south, Colonel Alexander von Pfühlstein’s 154th Infantry Regiment of the 58th Infantry Division pushed the Soviets back west of Myasnoy Bor. With temperatures still well below zero, the attacks continued for the next few days.

At 4:45 pm on March 19, units of Altrichter’s division reached Dora. The day before, Wünnenberg’s troops had taken Erika. Both groups moved tentatively forward in the thickly forested area, and on the 20th they met, slamming the door on the approximately 130,000 Russians inside the pocket.

Klykov reacted immediately by ordering several units inside the pocket to head east to reopen the corridor. From the 22nd on, the thin German lines were under constant attack from tank and infantry units and from artillery fire from the eastern bank of the Volkhov. A new operational group formed under Maj. Gen. Korovnikov battered the German forces, and by March 27 the Erika route was reopened. Another small land bridge was also established, giving the Russians two accesses to supplies, but the corridor had also shrunk to a width of three to five kilometers. During the next few days, Soviet engineers, working under horrific conditions, were able to construct two narrow-gauge rail lines inside the corridor to funnel supplies to the troops in the west.

“Roads Turned to Water”

In late March, the weather finally broke, and the Rasputitsa (muddy season) set in. The snow began to melt, and the swamps and bogs filled with water. Mud was everywhere, making movement extremely difficult. Getting supplies to the Soviet forces in the western area of the pocket was almost impossible.

“At the end of March, the roads turned to water,” platoon leader Yelokhovskii remembered. “Shells had to be dragged the five kilometers from the brigade’s supply at Dubovka. And how many shells could a hungry man carry?—two shells at the most, with each shell for a 76mm gun weighing 7.5 kilograms…. The food situation became quite bad. The horses, which had died during the winter, could still be eaten while frozen. But with the warm weather the corpses swelled up and maggots appeared….”

Farther north, the mud and stiff German resistance had brought the 54th Army’s drive toward Lyuban to an end. Stretched to the limit, the German lines bent, but they did not break. Even so, German commanders were not certain that they could hold Lyuban given the state of the divisions holding the lines, both at the Volkhov pocket and at the 54th Army’s bridgehead.

Throughout April, both sides were virtually paralyzed by the weather. The rainy season had set in with a vengeance, turning the ground into a quagmire that made any movement a fatiguing process. Inside the Volkhov pocket, Klykov used the respite to regroup his forces and integrate the replacements that were slowly making their way to the front into his units.

The Germans used the time to strengthen the perimeter of the pocket with reinforcements that were finally coming. However, any offensive operation to liquidate the pocket was out of the question for the moment since the mud made supplying anything but the basics for those troops impossible.

Replacing Generals

The deadlock also cost the jobs of commanders on both sides. Chappius was replaced by Hänicke. Blamed for the Soviet success in reopening the corridor in March, Altrichter was replaced by Colonel Karl von Graffon. On the Russian side, Meretskov’s Volkhov Front was combined with the Leningrad Front effective April 23, putting him out of a job.

On April 24, Meretskov was back in Moscow. Stalin was present at a Stavka meeting when Meretskov spoke of the dangerous position the 2nd Shock Army was in. “In its current state, 2nd Shock Army can neither attack or defend,” he said. “Unless it can be given reinforcements it should be withdrawn from the pocket at once. If nothing is done, a catastrophe is inevitable.”

A few days earlier on April 20, Lt. Gen. Andrei Andreevich Vlasov, Meretskov’s deputy commander, arrived at Klykov’s headquarters to take command of the 2nd Shock Army. Klykov was ill, suffering from fatigue. The abysmal conditions inside the pocket had also taken a toll on his health. The new commander was tasked with regrouping the 2nd Shock Army for either continuation of the offensive or pulling out of the salient. It was a daunting task considering the supply corridor was under constant German fire, which disrupted or destroyed the material making its way across the river to the pocket.

What Vlasov found was an army that was undersupplied and lacking artillery. Despite its impressive name, the 2nd Shock Army has lost many experienced officers and men. Those who remained were weak from hunger and inadequately trained.

Plans For Evacuation

By late April, Stalin’s winter offensive had stalled all along the Eastern Front. Overextended and running short of supplies, the armies were ordered to assume a defensive posture in most areas. However, German and Russians forces were still fighting it out in the Crimea, and Hitler was already making plans for Operation Blau (Blue)—the drive to Stalingrad.

In the Volkhov sector, Moscow finally realized the futility of continuing the Lyuban operation. As the ground began to dry, it was clear that the Germans would once again begin offensive operations to liquidate the pocket. On May 21, Khozin, who was now overall commander of the Leningrad Front, issued orders for Vlasov to prepare to evacuate the salient.

The evacuation would take place in stages, with the westernmost troops in the pocket falling back to a 30-kilometer line stretching from Ostrov in the south to about five kilometers west of Krassnaia Gorka in the north. Following that maneuver, the troops would retreat to the main line of defense, which curved about 35 kilometers from Volosovo to Ruch’l. Once that was accomplished, at least four rifle divisions that were guarding the flanks of the pocket would be freed to regroup and serve as a reserve force.

The final position would be a 25-kilometer line from Piatilapy to Krivino, about 35 kilometers west of the Volkhov. From there Vlasov’s army could make its way through the corridor to the eastern bank of the river. The withdrawal would be covered by attacks on the Germans by flanking armies (59th and 52nd).

The plan looked good to those who formulated it. However, it would need good logistics, communications, and cooperation between the participating Soviet forces—things the Russians had not yet perfected during this stage of the war, especially in the Volkhov sector. The 59th and 52nd Armies were separated by the corridor leading into the pocket and were weakened by the casualties incurred in the previous month’s fighting. As usual, reinforcements and supplies were slow in coming, which would also hamper their efforts.

The terrain and weather also continued to remain a problem. On the German side, Sgt. Maj. A. Gütte of Jaschke’s 20th Motorized Division noted: “The forests grew green and storm clouds darkened the skies. Mosquitoes swarmed over the swamps, tormenting the long-suffering soldiers, and neither gloves nor nets provided relief. With this plague came the almost unbearable nausea occasioned by the decaying flesh of the fallen lying in the swamps and woods.”

On the Russian side, Yelokhovskii recalled: “For the last days of April and all of May supplies were generally nonexistent. Aircraft would drop dry rations, but to what purpose? A sack would either fall into the swamp or strike a stump and break into dust. Some would glean the meager pieces from the mud, but there would be little at all to be found….”

The Red Army Retreat

The withdrawal to the first defensive line began on May 24. For the most part, the movement went unnoticed by the Germans, and the retreat continued until the main defensive line was reached on the 28th. By that time some units inside the pocket had already made their way to the eastern bank of the Volkhov. They would be the lucky ones.

The Germans finally realized what was happening during the final days of May. With the skies still pouring rain, there was little that could be done until the weather cleared. The sun finally appeared on May 30, and the Germans struck at the tenuous Soviet lifeline. On the south side of the corridor, the 58th Infantry and 20th Motorized Divisions, supported by the 2nd SS Brigade, moved forward to meet I Army Corps’ 254th, 121st, 61st, and SS Police Divisions.

Soviet positions were overrun after heavy casualties were incurred. The terrain slowed the advance as the Germans fought to gain a foothold on the high ground that held the Soviet supply corridors. Brig. Gen. Martin Wandel, commander of the 121st, watched his troops struggle to advance.

Pushing forward, the divisions of I Army Corps severed the Erika supply route. The next day, the divisions of Hänicke’s XXXVIII Army Corps linked up with the I Corps. The linkup did not wholly seal the corridor, as gaps in the line still remained, but it managed to cut once and for all the supply routes servicing Vlasov’s army. Once the divisions met, their commanders formed lines that faced east and west to prevent the Soviets from retaking the area. Other divisions on the perimeter of the pocket also moved to compress the area the Soviets held on the west bank north and south of the corridor.

With his escape route to the east blocked, Vlasov mounted an attack to the northeast, hoping to link up with the 59th Army, whose advance units had fought their way to the eastern bank of the Polist River. The attack came up against formidable German defenses on June 5 and fell apart. German counterattacks pushed Vlasov’s forces back into the ever shrinking pocket the next day.

Meretskov Returns to the Volkhov Line

On June 8 Stalin reestablished the Volkhov Front with Meretskov once again in command. The change did little to affect the situation. The 52nd and 59th Armies were slamming against the German lines, achieving little while suffering heavy casualties. Inside the pocket things grew even more grim.

Communications between Vlasov and Meretskov were lost on the night of June 21, leaving the Volkhov Front commander totally in the dark as to the dispositions of the 2nd Shock Army’s formations. Nevertheless, some Soviet troops were able to escape from the pocket when a group of Vlasov’s soldiers opened a narrow corridor to the advance elements of the 59th Army. More than 6,000 men were able to make their way to freedom before German counterattacks, supported by Stuka dive bombers, closed the escape route. Other smaller groups found gaps in the German lines and made it to safety, but most were cut down by German fire as they tried to escape.

By June 25, the Germans had totally sealed off the corridor near the Volkhov after fighting off several attacks to reopen it. Inside the pocket the agony of the 2nd Shock Army continued. German forces had split the pocket into several pieces on June 23, further hampering any wholesale breakout attempt. The lack of communications between units, even between units subordinated to battalion or regimental headquarters, resulted in the further disintegration of the starving army. By the end of the month, the battle was over.

The 20th Motorized Division’s Sergeant Major Gütte recalled, “A last desperate attempt to break out of the encirclement was beaten back by dive bombers. The pocket was then split and the end point arrived. The Russian troops emerged from their hiding places in the hundreds and thousands. Many were wounded. Most of them were half-starving and barely retained the semblance of human beings!”

SS Private Sayer, a member of Wünnenberg’s Police Division, also described the end of the battle: “On either side of the path a portrait of misery wherever the eye fell! Our route led us past the dead and wounded or columns of half-starved Russian soldiers…. When day broke, we saw where we were for the first time. We already knew we were on a corduroy road, but what was on and along the road—that was something we had never seen before. Hundreds of motor vehicles, guns and weapons of every kind had gotten stuck there. An immense mass of war matérial of every kind was strewn around. And then the mass of prisoners arrived from all sides—wounded, ragged and totally fought-out figures, gnawing the bark in their hunger—they came and came—there was no end!”

149,000 Casualties For the Soviet Union

The woods yielded about 33,000 prisoners. Total Russian losses for the Lyuban operation from January 7 on were approximately 149,000 dead and 253,000 wounded for the 2nd Shock, 52nd, and 59th Armies. Most of the blame for the fiasco has to be placed squarely at the feet of Stalin and Stavka. The logistics failures, use of half-trained and inexperienced troops, and the several ordered halts of the operation made its objectives nothing more than a pipe dream. However, a convenient scapegoat for the failure was found in Vlasov.

Since losing communications with the outside, Vlasov had wandered aimlessly from unit to unit in the pocket. On July 21, the Germans received a report from a village mayor that two partisans were hiding in his town. The operations officer of the XXXVIII Army Corps, a Captain von Schwerdter, took a patrol to the village and confronted the pair. They turned out to be Vlasov and his female cook.

Vlasov was treated somewhat as a celebrity. During the next two years he was visited by several prominent officials, including anti-Soviet Russian officers. Eventually, he was convinced to sign leaflets encouraging Soviet troops to desert. In March 1943, he wrote an open letter titled, “Why I decided to fight against Bolshevism.” Although his plans for a Russian movement composed of anti-Soviet prisoners never got off the ground, he was given the command of two Russian divisions in late January 1945.

Captured by Soviet troops at the end of the war, Vlasov was taken to Moscow for trial. Among the charges leveled against him were treason and cowardly actions, which purportedly led to the destruction of the 2nd Shock Army. After the three-day trial, Vlasov and 11 of his associates went to the gallows on August 1, 1946.

Nice article. But can I know what is “NOG xxx” in the map? Which corps?

Northern Operational Group (Cavalry, Partisans and various infantry/mountain formations).