By Flint Whitlock

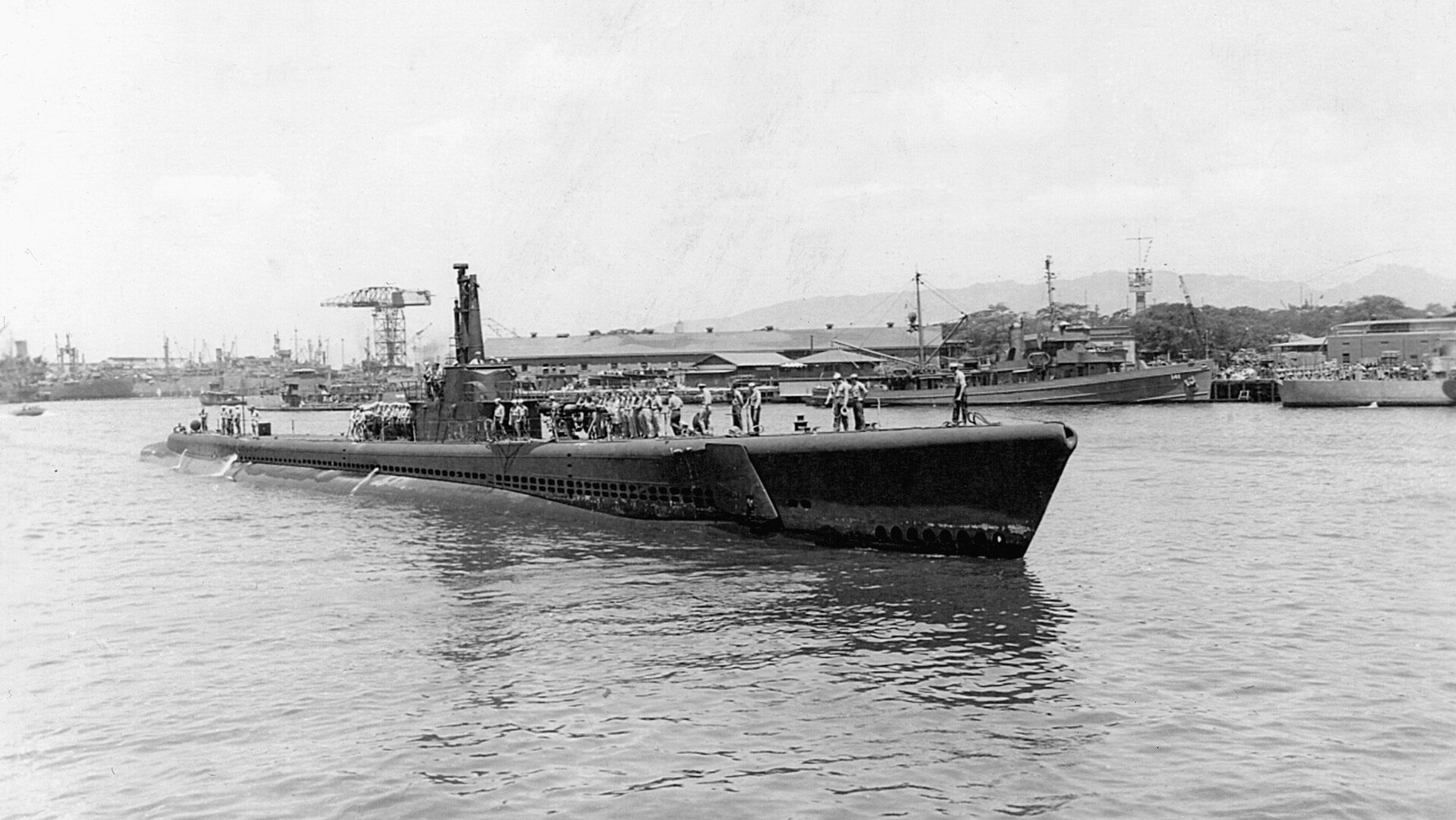

During World War II, the United States employed 288 submarines, the vast majority of which raided Japanese shipping in the Pacific, thus preventing the enemy’s vital supplies and reinforcements from reaching the far-flung island battlefields. One of the most outstanding of those 288 submarines was the USS Tang, launched on August 16, 1943, at the Mare Island (Calif.) Navy Yard. Her commander, Richard O’Kane, a 1934 graduate of the Naval Academy, would earn the Medal of Honor and the Tang would receive two Presidential Unit Citations. Only one other submarine was so honored.

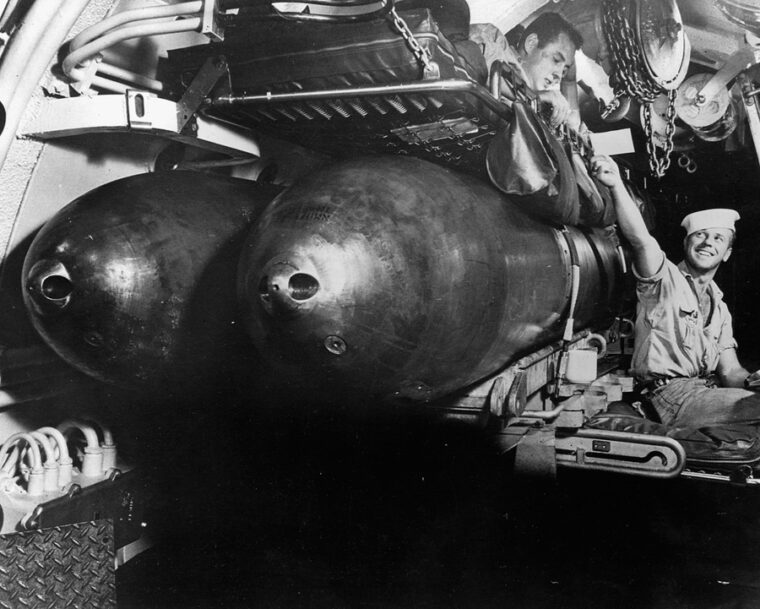

Malfunctioning torpedoes plagued the Navy throughout much of World War II; “fish” that veered off course or failed to detonate when they struck their targets were not uncommon. On March 26, 1944, while on her fourth war patrol off Palau, the USS Tullibee became the first American submarine in World War II to be sunk by one of her own torpedoes. Of the 80-man crew, only one survived.

The only other submarine to be sunk by a wayward torpedo was the Tang. On her fifth war patrol, October 24, 1944, between China and Formosa (today Taiwan), an errant torpedo circled back and sank her, killing most of her crew. One of only eight men to escape was Motor Machinist’s Mate Clayton Decker.

Motor Machinist’s Mate Clayton Decker’s Story

WWII HISTORY: Mr. Decker, please give us a little of your background.

DECKER: I was born in Paonia on Colorado’s Western Slope in 1920. When I was seven, we moved to Menlo Park, California. After my freshman year in high school, I returned to Colorado, finished high school, then enrolled at Colorado A&M in Fort Collins (today Colorado State University). I was also married and had a two-year-old son. In December 1942, I quit school and joined the Navy.

WWII: Why the Navy?

DECKER: The one thing I always heard about the Navy was that your bunk and the chow hall went right along with you. That appealed to me. I went to torpedo school in Norfolk, Virginia, graduated as a Third Class Torpedoman, and selected the submarine service. The submarine branch is strictly voluntary, and you got extra pay. I needed that extra pay because I had a wife and son. During the summer, while I was in college, I worked down in the coal mines in Paonia, so I knew I didn’t have any problems with claustrophobia.

WWII: How did you get assigned to the Tang?

DECKER: The Navy sent me to submarine school at New London, Connecticut; I spent three months there, then went to Mare Island, California. I was assigned to the Tang—a new submarine that had just been built and was about to be commissioned. World War II submarines were named after fish, and I’m told the Tang is a tropical fish.

I was on the commissioning crew for the Tang in October 1943. I went through the trial runs. We made our shakedown cruise from Mare Island Naval Shipyard in Vallejo, California, down to San Diego for deep-diving tests and to see if the boat was seaworthy. On January 8, 1944, we arrived at our home base at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii.

WWII: How many combat patrols did the Tang make during the war?

DECKER: We only made five patrols, and on our second patrol, we never fired a torpedo. I’ll tell you about that one in a minute. During World War II, the average patrol was about 70 days. The two determining factors for the length of a patrol were fuel and ammunition. We carried 24 torpedoes—10 tubes forward and four tubes aft. In order to have a successful patrol and get a star in your combat pin, you had to sink at least one enemy ship. In terms of ships sunk and tonnage sunk, the Tang was number one. Some other submarines had from 10 to 15 patrols; we were number one with only four patrols.

WWII: You must have had an outstanding commander.

DECKER: Dick O’Kane was without a doubt the finest submarine skipper in the entire Navy—an absolutely first-class officer.

WWII: What was your job aboard the Tang?

DECKER: Well, my rating was torpedoman. In those days, very few of the submarines had boatswain’s mates, but we had one. His name was Bill Leibold. The boatswain’s mate was in charge of all “right-arm ratings,” and a torpedoman was a right-arm rating. Bill Leibold really cracked the whip, and I guess I didn’t live up to his expectations, so I was broken down to seaman first class and sent down to the “black gang.”

On our first patrol, our executive officer, Murray Frazee, selected me to be permanent bow planesman. He said he selected me because I had a “knack for catching the bubble.” That’s a glass arc tube with a bubble in it. When we started to dive, I’d have to rig the bow planes—they looked like big elephant ears. I sat on a bench forward of the control room with a big wheel in front of me, like a steering wheel in a car. Right behind me was the bulkhead where the radio shack was. I was kind of wedged in there.

On our first patrol, in February 1944 in the Marianas, we had 16 hits in 24 attempts. Our third patrol was in June and July and went from Pearl to the East China Sea and Yellow Sea, where we sank 10 ships. All totaled, on our four patrols, we were credited with sinking 31 ships with a combined tonnage of 227,800.

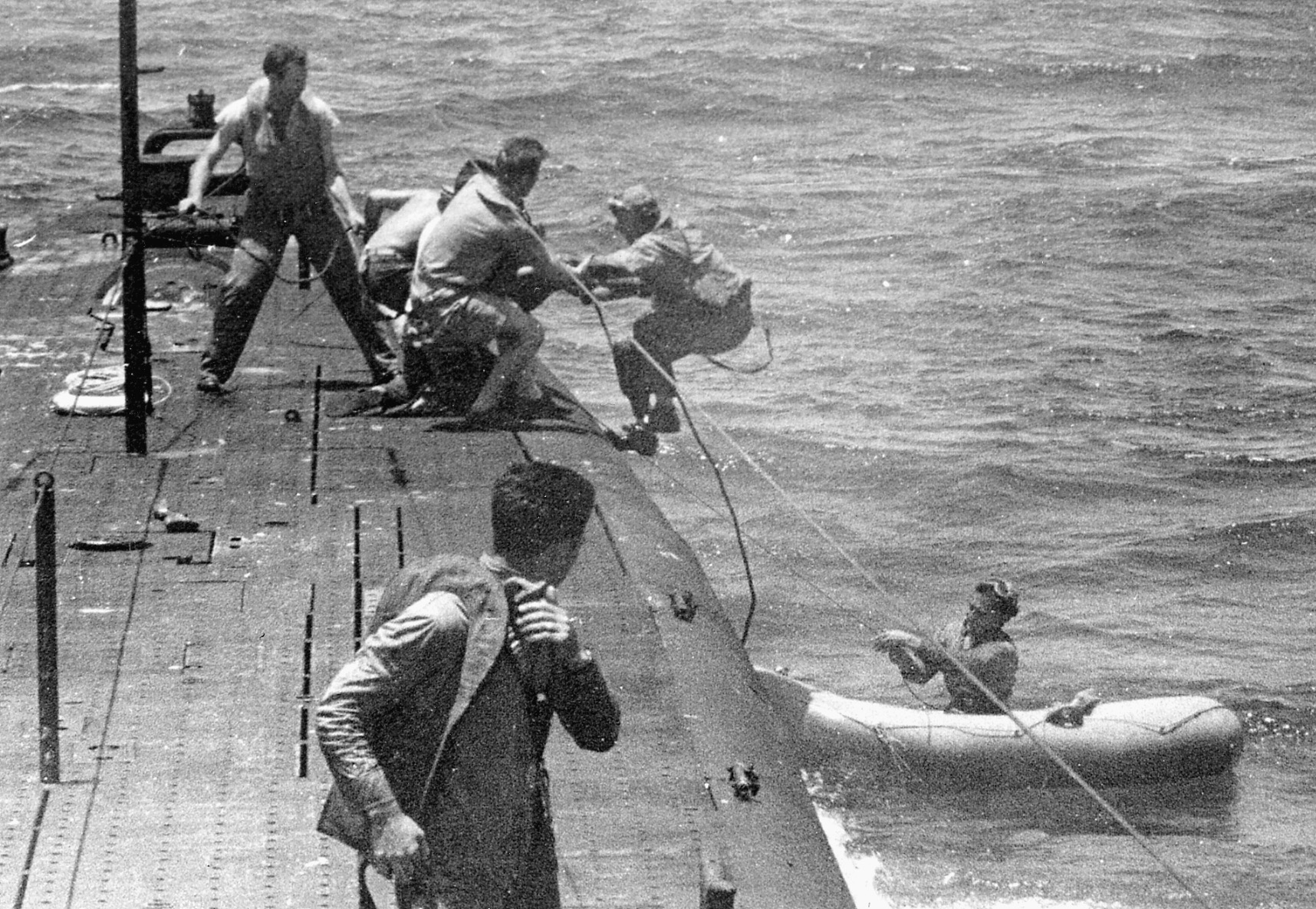

WWII: What about that patrol on which you didn’t fire any torpedoes?

DECKER: That was our second patrol, in March 1944. While we were out, we received a message to rescue a bunch of Navy carrier pilots who had been shot down during the battle of Truk Atoll. We pulled 22 flyers out of the water; they weren’t hurt physically. We had a crew of 87 and now we had an extra 22 to accommodate—talk about “hot bunking!” Admiral [William F.] Halsey wanted all of those flyers back in service as fast as he could get them, so we went back to Pearl Harbor. We did not get a star in our combat pin for that patrol, but Admiral Halsey gave every member of the Tang crew the Navy Air Medal. That really causes a lot of conversation at a submariners’ reunion—submariners with the Navy Air Medal!

WWII: I’ll bet!

DECKER: Our fifth and final patrol was from Hawaii to the Formosa Straits, between Formosa and Foochow, China—some of the shallowest water in the Pacific. We used to hate to patrol there because it was only 200 feet deep or less. We knew the Japs could set off depth charges at 200 feet. A depth charge is nothing more than a 55-gallon drum half full of TNT. When it gets flipped into the sea, it takes on saltwater and sinks. We weren’t too fearful of a depth charge going off above us or to the side. But if it went off below us, it could blow the water out of our ballast tanks and give us positive buoyancy and pop us to the surface like a cork. We’d be a sitting duck for whoever was after us.

WWII: Tell us a little more about these ballast tanks.

DECKER: The submarine is like a cylindrical tube. Surrounding that tube are the ballast tanks, with flood valves on the bottom and vent valves on the top. When we’d go on a patrol, we’d open the flood valves and lock them open; you don’t maneuver with them—you do all your maneuvering with just the vent valves. An empty ballast tank has air in it. When you open the vent valve, you let the air out and water comes in the flood valve immediately, giving you negative buoyancy. That’s what a submarine needs to take it down.

The Tang’s Last Patrol

WWII: What about your fifth patrol?

DECKER: We were on station in the Formosa Straits for almost a week and a half. It was two in the morning, October 24, 1944. The pips on the radar screen showed a convoy of 35 ships. We steamed over and, sure enough, it was a convoy. Our troops were landing on Leyte then and the Japs were apparently sending this supply convoy to Leyte. There were also a goodly number of destroyers and destroyer escorts, which we didn’t like because they were the guys with the depth charges. Normally, the convoys would zigzag, two abreast. In this case, they were all in a line, really rolling on. It was just like a shooting gallery for us.

Skipper O’Kane decided to get ahead of them and wait for them to come on. Now, after you attack, you have to get away from the action because they’re mad; they’re hunting for you. Also, the boys responsible for reloading the torpedo tubes had to do it with a block and tackle; they couldn’t reload if we were maneuvering. So after we fired, we got away from the action, stopped, reloaded, then resumed the attack. Of these 35 ships, we sank 13.

One of the ships was a transport loaded with, according to the skipper’s best guess, about 5,000 Japanese soldiers. We hit it astern with a torpedo and stopped its propulsion, but didn’t sink it. With two torpedoes left, we approached that crippled transport under cover of darkness. I’m sitting at the wheel just below the hatch that goes up to the conning tower; there’s a fire-control party up there with the skipper watching the action and giving all the orders. I’m hearing everything that’s going on over the intercom.

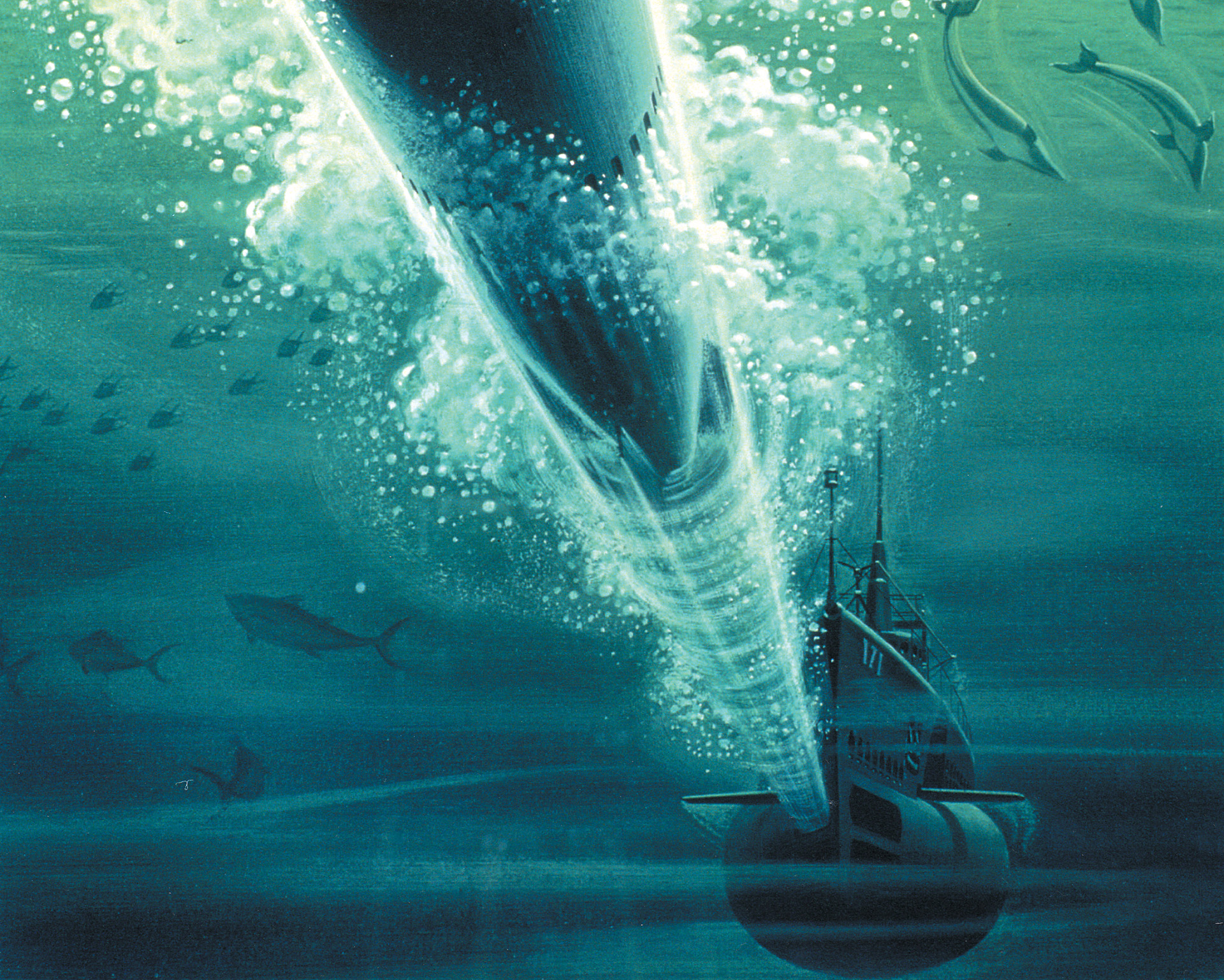

Normally, we would fire torpedoes at a range of 1,000 to 1,500 yards; we went in on that target at 700 yards. Normally, we would have one or two knots on the screws, but we were all stopped. Skipper had two torpedoes left with an injured transport sitting dead in the water, and he didn’t want to miss. So we fired our last two torpedoes. Number 23 went out straight and hot and hit the target amidships.

You don’t want to hit a ship at the water level; all you’ll do is blow a hole in her. They have water-tight compartments and they’d seal off that compartment and stay afloat. But if you hit it just above the keel, you’d sink her. So our torpedomen set the depth into the memory of the torpedo so it would hit a foot or two above the keel. That would break her back and down she’d go. That’s exactly what the 23rd torpedo did.

Hit By Its Own Torpedo

WWII: So now you have one torpedo left.

DECKER: Right. The men on the bridge who survived said the last torpedo came out of the tube, went about 300 yards, then came up dancing out of the water. When it dropped back into the water, it had a hard left rudder on it. It circled around on our port side and hit us just ahead of the aft torpedo room and sank us immediately. We started sinking from the stern.

The explosion threw the lads who were standing in the compartment where I was sitting across the compartment and against the steel bulkheads. The hatch immediately above me was open and water started rushing in. Those lads who were in the conning tower crashed head-first down the ladder onto the steel deck of the control room. We had one man with a broken back, one with a broken neck, two men with broken arms, another with a broken leg. And the lads who were thrown around the control room, they had bashed heads and bleeding faces. Luckily, because I was wedged into my duty station, I didn’t move more than four or five inches.

WWII: It must have been total chaos.

DECKER: It was. Everything went pitch black. I have to say that, to qualify to be a submariner and get your dolphins, you had to be able to go through the boat with a qualifying officer and identify everything. We had over 5,000 valves, lines, gauges, everything. The officer would point to something and ask, “What is it?”

“What’s in there—air, water, or fuel?” Fortunately, I had qualified on our second patrol, so I knew everything in the boat. When that torpedo hit us, I knew exactly where the emergency lighting switch was located and I turned it on immediately. Right after that, I went to help Bill Ballinger, the chief of the boat. He was bleeding from the forehead. He said, “Clay, we aren’t going to be able to get forward to the escape chamber unless we get the boat level.”

We were sitting at about a 45-degree angle with the stern resting on the bottom of the sea in about 180 feet of water. We were also taking on water; it was pouring down the open hatch. When the last man in the conning tower came down—he had a broken arm—he reached up and grabbed the rope lanyard that was attached to the hatch, which is spring-loaded, and pulled it down. But the lanyard had a little piece of wood like a handle on the end and it flipped up and got caught in the rubber gasket around the hatch. He closed the hatch and dogged it down, but it wasn’t sealed, so we still had a stream of water coming in.

WWII: What about the men in the stern sections?

DECKER: I’m afraid they all perished. Anyway, I knew that the bow was sticking out of the water because we could hear the waves slapping against the hull. We knew we had to get the Tang level so everyone could go forward to the forward torpedo room where the escape chamber was. To do this, the forward ballast tanks would have to be flooded to get the boat level. All controls on a submarine that were operated hydraulically could also be operated manually. The manual lever that opened the vent valves on all the forward ballast tanks was located right over the chart desk in the control room. It was a steel lever facing aft and hinged forward. Without receiving any orders, I crawled onto the chart desk, turned over onto my back, threw my legs over that lever, pulled the pin, and swung down; the Tang just leveled out and settled on the bottom.

WWII: What happened to O’Kane and the others who had been on the bridge?

DECKER: O’Kane had been up there along with Bill Leibold and Floyd Caverly and another officer, Larry Savadkin. They all made it into the water and were picked up by the Japs later.

Trapped at the Bottom of the Ocean

WWII: So now you and the rest of the crew are on the bottom of the ocean.

DECKER: Right. The diving officer—Lieutenant (j.g.) Fred Enos—was the youngest officer aboard the Tang, and he was really a babyfaced lad. He was one of only two officers still with us. We started forward—I’m helping Ballinger. We get to the officers’ quarters and here’s Enos. He’s gone into the skipper’s cabin and got all the code books and put them in a wastebasket and is touching a match to them. Right away, I stopped him. I said, “You can’t do that, Enos, you can’t do that! We can’t have a fire going! We need every bit of air we’ve got!” Plus, we had these huge batteries below there; you couldn’t have any sort of spark around them.

WWII: So what did you do with the code books?

DECKER: The batteries were full of sulfuric acid and had big openings, so we shoved the code books into the batteries and the acid ate them up.

We eventually got 30 or 32 men together in the forward torpedo room. When we got there, we put the guys with broken bones up in the bunks. There was no use of them even trying to escape—there was no way they would be able to make it. They seemed resigned to their fate.

We estimated there were about four or five hours of air left. We had to get the escape plan going within that amount of time or we’d all be in a coma. But there was no panic; everybody was calm.

Whenever you get a group of men together, you always have a couple of know-it-alls. We had a couple of them—one in particular. This loudmouth and a chief torpedoman had crawled into the escape chamber before the rest of us got organized. They didn’t have a Mae West or a Momsen lung, but they flooded the chamber, opened the hatch, and went out on their own. We never saw them again.

WWII: What’s a Momsen lung?

DECKER: It straps onto your chest like a Mae West and has a nose clamp and a mouthpiece right below it. When you get to the surface, if you close the valve, you can use it for a life preserver. We had over a hundred of them onboard. The lung had a little relief valve that looked like a piece of flat rubber. It wouldn’t let water in but would let air out when you exhaled. There was also a canister of soda lime in the lung. When you exhaled, the carbon dioxide would go through the soda lime, which would absorb the free carbon and give you free oxygen. That’s the principle of the Momsen lung.

WWII: What an ingenious device.

DECKER: Yep. You charged them either with straight oxygen if you’re less than 200 feet below the surface or compressed air if you’re more than 200 feet. It’s got a valve on it just like a bicycle tire. In our case, we used straight oxygen. The Momsen lungs we had onboard were brand new, never been used. They were in sealed cellophane bags. The ones we had in training in New London were all used. I’ll tell you why this is important in a minute.

The Escape from the Tang

WWII: Please describe the escape chamber.

DECKER: It was about the size of a phone booth. Four men could squeeze in there at the same time. There were three main gauges—a fathometer that shows how deep you are, a gauge that tells you the air pressure in the chamber, and another one that shows what the exterior sea pressure is. What you did was, before you got in the chamber, you put on the Momsen lung and the Mae West. Right above you in the chamber is the escape hatch. Above that is an opening in the deck, about three feet square.

After you rig the escape hatch and get ready to ascend, you put out a wooden buoy about the size of a soccer ball that has a lanyard stapled around it and a hand-hold that you can grab. This buoy has a line attached to it and a spool in the escape chamber with a knot in the line every fathom, or six feet. You let that buoy out and it pops to the surface. You then sever the line and tie it onto the rung of a ladder just outside the escape chamber. Outside it’s pitch dark. You can’t tell which direction you’re going unless you’ve got a hold of that line. You never let go; many of the guys who didn’t make it didn’t get a hold of that line. If you were outside and lost your grip on the line, you wouldn’t know whether to turn right or left or what—you would panic. You would start to go up and your head would hit the underside of the deck and you’d be hung up in the superstructure and drown. That’s exactly what happened to a lot of the guys.

Anyway, we let water into the chamber up to our chests, then we opened a valve to let air pressure in so you’re standing with your head in an air bubble. You let that pressure build up to exceed the sea pressure by five pounds. That way, the hatch going out to sea opens just like a door in a room. You just push up and it opens—no problem. If you tried doing that before you built up five pounds of pressure, you couldn’t possibly get the hatch open.

After those first two guys went out, we closed the outer door and drained the chamber. Bill Ballinger said, “I’m going to go in the first wave of four. I need volunteers.” I stepped right up.

About that time, George Zofcin came in from the engine room. George was a good friend; his wife and my wife were sharing a house in San Francisco while we were at sea. I helped Zofcin put on his Momsen lung and he helped me with mine. I also had a .45-caliber pistol and a shark knife.

I said to George, “Come on, let’s go with Bill.”

George said, “Clay, I’ve got a confession—I can’t swim.” I have a picture of us frolicking on Waikiki Beach in Hawaii, and he’s right—he never did go in the water. I found out later that, after I went out, George crawled up into a bunk and waited to die. Didn’t even try to escape.

So Bill Ballinger and I and two other new guys on board got into the chamber. Bill had the air hose and gave us all a charge. He told each one of us to duck down into the water to test the Momsen lungs. They were all working fine. He said to me, “OK, Clay—go for it.”

He gave me the buoy and I let it out. I counted the knots. It was 180 feet. He severed the line and I secured it to the ladder. I went out. At 180 feet, I had 6,000 pounds of pressure against my body. But, remember, I’ve got pressure inside, pushing out. As I ascended, to keep from getting the bends, I stopped at each knot, exhaled, inhaled. As I started up that line, I saw bubbles coming out of that relief valve, going up and passing me. If you do this properly, by the time you get to the surface, you’ve equalized the pressure.

When I get to the surface, I reach up to take off my nose piece and I notice I’m bleeding—my nose is bleeding and my cheeks are bleeding. I later found out that I probably came up faster than I should have and the little blood vessels in my nose and cheeks broke. I spit out the mouthpiece and the lung filled with saltwater. I couldn’t use it as a Mae West now, so I took it off and let it go. There were handholds on the buoy, so I grabbed it and got rid of the .45 and shark knife. It was just about dawn at this point.

WWII: What about the other three men who were in the chamber with you?

DECKER: Bill Ballinger came up. He was no more than four feet away from me and he’s drowning. He’s screaming, he’s vomiting. If you don’t believe in the Man Upstairs, I want to tell you something. A voice told me, “Don’t touch that man! Don’t you reach out and touch that man! Absolutely don’t do it!” I was told later that if Ballinger had touched me, I wouldn’t be here today. It’s a known fact that a drowning man can pull a horse under water. If he’d gotten a hold of me, I’d have drowned with him.

Here’s what we figured happened: the relief valve on a new Momsen lung was folded with a clip around it. When George Zofcin helped me put on my lung, he took the clip off. I surmise that Bill Ballinger didn’t take the clip off his, so his lungs burst because there was no way for him to exhale.

Taken Prisoner by the Japanese

WWII: What about the other two men?

DECKER: The other two boys in our first wave never came to the surface. We figured they got out of the chamber but let go of the line and got trapped in the superstructure. In the next wave of four, only one man made it. It was Lieutenant (j.g.) Hank Flanagan. Eventually, there were six of us in the water for about five hours. The last man to come up was in bad shape; he had taken on a lot of water and was close to drowning.

Finally, the same Jap destroyer escort that picked up O’Kane and the other three guys—the P-34—picked us up. They had a whaleboat and were rowing it with their rifles. They rowed over to us and we got aboard and they rowed back to the P-34. I was the last man up the ladder. I looked back. The Japs didn’t even try to give CPR to the drowning guy; they just dumped him over the side. That made five of us. We got up on the steel deck and here’s the skipper and the three other officers. Now there were eight survivors total from the Tang. Those of us who used the Momsen lung are the only ones who ever escaped from a sunken submarine and lived to tell about it.

On this destroyer escort, there were survivors from the ships we had sunk. There were guys who had been down in those engine rooms who had been scalded by steam—they looked like lobsters. They’re looking at us with hate in their eyes—we’re the guys who had done this to them.

We then got the worst treatment we had all the time we were prisoners. We submariners were fair-skinned; all we had on were our shorts, and they kept us on this hot steel deck under a blazing sun for five days and five nights. We were a mass of blisters. Those Jap survivors would grab us by the hair and stick lit cigarettes up our noses. They just beat the s*** out of us. No water, no food. We thought, this is the end.

WWII: Where did they take you?

DECKER: To Formosa. They tied our hands behind us, put black hoods over our heads, a line around us, and marched us through Taipei, the capital. They made us hold up a sign that said something like, “Here’s an example of the superior race.” Little kids and old ladies came out and hit us with sticks.

Then they took us to an army camp outside of Taipei and threw us in a potato cellar overnight and we all ate raw potatoes. Didn’t wash them or anything. The next day they took us to a port and put us on a ship loaded with sugar that was going to Yokohama. From there we went inland to a POW camp called Ofuna, near Yokohama. We were there until February 1945. We were beaten, tortured, starved. We came down with scurvy and beriberi. Our one source of entertainment was American air strikes on Japan. From Ofuna we went to the camp at Aomori, which was an island in Tokyo Bay.

From February to August 1945, my cellmate at Aomori was Greg “Pappy” Boyington, the Marine pilot of “Black Sheep Squadron” fame. He had been shot down over Rabaul about a year earlier; he also had been at Ofuna. We weren’t classified as POWs—we were “Special Prisoners of the Empire of Japan.” They claimed that when we sank Japanese ships, 90 percent of the persons on board were civilians. We were accused of making war on civilians and so weren’t entitled to POW status. As a consequence, we only got half the normal food ration and we weren’t allowed to mingle or associate with any other prisoners in any of the camps we were in.

After the war ended, we were liberated. It was August 28, 1945. Twenty-one prisoners were on the first flight back to the United States, and I was that 21st person. Twenty officers and this one enlisted man. I asked Boyington, “Pappy, did you get me on this flight?”

He just grinned and said, “Aww, Deck, I didn’t have anything to do with it.” But I know he did.

Giving the Tang Full Credit for Its Combat Success

American submariners in the Pacific compiled an outstanding combat record and played a major role in strangling Japan’s wartime economy. U.S. submarines sank nearly five million tons of shipping, including 1,113 merchant ships and 201 warships. The victory was costly, however, as 52 submarines and 3,505 submariners were lost. But, undeniably, the courage of those in “the silent service” made a tremendous contribution to victory in the war for America and her Allies.

After the war, O’Kane, by then a rear admiral, felt the Tang had not been fully credited for all the enemy ships it had sunk. By piecing together official U.S. and Japanese naval reports, he arrived at 31 official sinkings, for a total of 227,800 tons. No other American submarine had sunk more.

When Clay Decker’s flight landed at the Oakland (Calif.) Naval Air Station, he immediately called his wife to let her know that he was home safely; he received another jolt—believing him to be lost at sea, she had remarried in his absence.

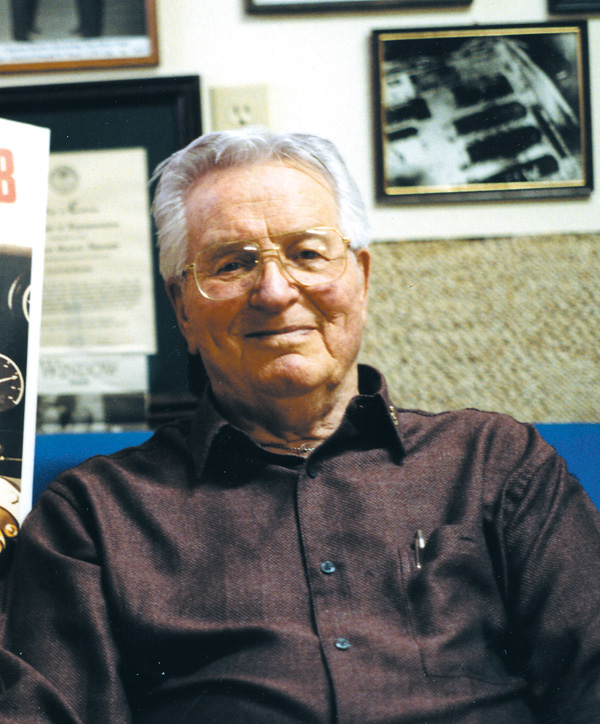

Clay Decker received the Silver Star, returned to Colorado, and in 1947 married Anne Reinecker; they had a son and a daughter. He was a district supervisor with Skelly Oil for 15 years before starting his own company, Decker Disposal. He retired in 1986 but remained active in veterans’ affairs.

On Memorial Day weekend, 2003, at the age of 82, he passed away, proud to the very end that he had been a member of the storied Tang.

Flint Whitlock, author of numerous articles and books on World War II, writes from Denver, Colorado.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments