By Blaine Taylor

On August 12, 1772, a wandering Don Cossack named Emelian Pugachev crossed the Polish frontier into Imperial Russia on an official passport that entitled him, after spending six weeks in quarantine, to resettle as a free citizen on the Irgiz River in southeast Russia. It was a strange crossing. One of the border guards said to another, “You know, this man looks like the double of Peter III,” the former czar who had been deposed and murdered by his wife, Empress Catherine II, nine years earlier. Since few Cossacks had ever seen the real czar, who could say definitively that this was not he?

Pugachev laughed at the suggestion. A shabby, bearded man, only five feet, four inches tall, he hardly cut a regal figure. But the border guard persisted. “I’m not joking,” he told Pugachev. “You’re the spitting image of Peter III.” He should know, claimed the guard, since he had been a guardsman at one time in the royal capital at St. Petersburg.

From this almost comical suggestion began a revolt of Cossacks, factory peasants, and serfs that would last for two years and encompass fully a fifth of the empire’s population, spreading from the Caspian Sea to the Ural Mountains and the gates of Moscow. Pugachev’s Rebellion, as it came to be known, would shake Catherine’s throne to its very foundations.

The Time of Pugachev

Pugachev, a former junior lieutenant in the Russian Army, was a symbol of a smoldering revolt that had been waiting for some time for a proper leader to fan its embers into flames. The long-oppressed Cossacks and the religious brotherhood known as the Old Believers supported Pugachev just as they had his predecessor, Stenka Razin, a century before. The Old Believers had been excluded from mainstream Russian life for a century by Peter the Great, often living in remote Siberian settlements in order to worship freely. Razin’s 1670 revolt was brutally suppressed, and a second revolt in 1771 resulted in hanged Cossacks mounted on gibbets or floated down the Volga River as an example to other would-be rebels. Sill others were beheaded, and their heads mounted on spikes atop wagon wheels to which their broken bodies were also lashed.

Although he was certainly discontented with the way things were, Pugachev did not begin his bloody career as a rebel, but rather as a lowly soldier in the czarina’s army fighting the Prussians in the Seven Years’ War. He later fought in the First Russo-Turkish War of 1768, and at the Battle of Bender in 1770 he was taken ill and sent home on sick leave.

En route home, Pugachev used his invalid’s pass to visit his sister at Taganrog, where he discovered to his dismay that his personal grievances were the same as those of the Cossacks in general. Pugachevshchina—Time of Pugachev —as a movement did not start with Pugachev himself. Instead, like a swimmer on the crest of a wave, he allowed himself to be carried along by it. Either the wave would carry him to the far shore or else it would crash him onto the rocks. In Pugachev’s case, it did both.

An Inspiring Leader

Despite limited experience as a commander, Pugachev proved to be an inspired leader, issuing grandiloquent manifestos in towns he surrounded, and by managing to scratch out his “signature” as best he could, cleverly hiding from his own subordinates the fact that he was illiterate. With the help of local priests and mullahs, he disseminated his “royal decrees” to the masses in both the Russian and Tatar languages, promising the faithful more land, salt, and grain as well as significantly lower taxes. Those who refused to obey were royally threatened. “If there are those who forget their obligations to their natural ruler Peter III, and dare not carry out my command,” said one decree, “they will see for themselves my righteous anger, and will then be punished harshly.” Once, when he captured an astrologer, Pugachev had him hanged so that the man “could be closer to the stars”—an example of his cruel sense of humor. He also threatened to lock the notoriously promiscuous Catherine in a monastery. Suitably inspired, religious leaders prepared heroic welcomes whenever the Pretender entered their villages, greeting his arrival with ringing bells, icons, salt, and holy water.

Cossack troops at frontier stockade posts betrayed their officers and threw in their lot with Pugachev. His subordinates, emboldened, urged him to march on Moscow immediately, but Pugachev hesitated, like Razin before him, opting instead to fight pitched battles and besiege scattered forts in the steppes that he knew so well. Also like Razin, Pugachev was truly a man of the Russian soil, not a foreigner like the empress he sought to defeat. Catherine contributed to her own woes by refusing to take the rebellion seriously, placing an insultingly low bounty of 500 rubles on Pugachev’s head. Lack of transportation and discipline—always Russian military weaknesses—further hampered the government’s initial efforts to control the outbreak.

Amassing an army through the artful use of propaganda and the long-deferred promise of reform, Pugachev was able to expand his rule from the Volga River to the Urals. No coward, he believed in leading his men from the front, taking part in battles for towns and fields. Over the course of his short life, he was captured and he escaped several times. As time went on, he warmed to his new role as Czar Peter III, asking his men while leading one assault, “You think they make cannons to shoot at czars?” His men responded to his imperial style of leadership, calling out to one besieged post: “Don’t shoot and come out of there! His Majesty is here.”

The Army of Pugachev

Armed with lances, axes, hatchets, pistols, and a smattering of rifles and guns, Pugachev’s men fought on foot, on horseback, and sometimes on skis. As for the besieged garrisons, they were reduced to eating horses, dogs, and cats when their normal rations ran out. Time and again, Pugachev would defeat more traditional Russian commanders and their czarist forces in open combat, or else employ guerrilla tactics and melt into the countryside.

Greatly alarmed when Pugachev at last turned his attention toward Moscow, Empress Catherine responded by sending into battle ever more powerful forces, led by her best available field commanders as the Turkish war finally wound down. Pugachev defeated all comers before General Alexander Suvorov arrived from the Turkish front along with Count Peter Ivanovich Panin, a relative of Russia’s foreign minister.

“Half in Reality, Half in a Dream World”

The net was closing in on the Pretender, but each time the noose seemed to be tightening irrevocably, Pugachev would somehow make another hairbreadth escape. At the Battle of Tsaritsyn in August 1774, pro-government schoolboys battled Cossacks armed with only their bare fists, while “a sea of fire spread over the whole city,” according to novelist Alexander Pushkin. Pugachev was defeated twice in his efforts to take Tsaritsyn, but managed to keep Pugachevshchina afloat, only to lose the town yet again to Lt. Col. Ivan Mikhelson.

Despite the defeats, Pugachev continued to enjoy holding court as Czar Peter III, surrounding himself with a personal guard of 25 well-armed Yaik Cossacks. Wearing a magnificent red coat trimmed with gold lace, the Pretender would sit in his imperial chair of judgment, scepter in one hand, silver axe in the other, while supplicants knelt and kissed his hand. He would then walk among his troops flinging coins to them and practicing his oratory on new recruits. “O children,” he would cry. “God brought me to reign over you.” He explained his nine-year absence from the public eye by claiming that he had been living in exile in Jerusalem, Constantinople, and Egypt, praying and meditating, before returning to lead them to victory.

In a sense, Pugachev had become both Czar Peter and himself. As one observer noted: “Pugachev lived half in reality, half in a dream world. He would use high-sounding phrases one moment and coarse provincial epithets the next. He would consort with the wives of Tatar chiefs at Kargal and entertain his cronies to lavish meals, cooked by two Russian girls in his household, where he and his Cossacks behaved like brothers, drinking and singing songs together. He would suddenly lapse from his dignified pose and begin to wink.”

Pugachev began to get sloppy in his impersonation, and after more and more Don Cossacks joined his force, some recognized the Pretender for one of them. When he indulged himself in an ill-advised marriage to a local Cossack girl, the ceremony was widely discredited because the local peasants thought he already had a wife in St. Petersburg: Empress Catherine. His marital troubles were compounded when his first wife showed up one day in camp with their children in tow and denounced Pugachev as “a dog and a faithless villain” for deserting his family.

The Legacy of Pugachev’s Downfall

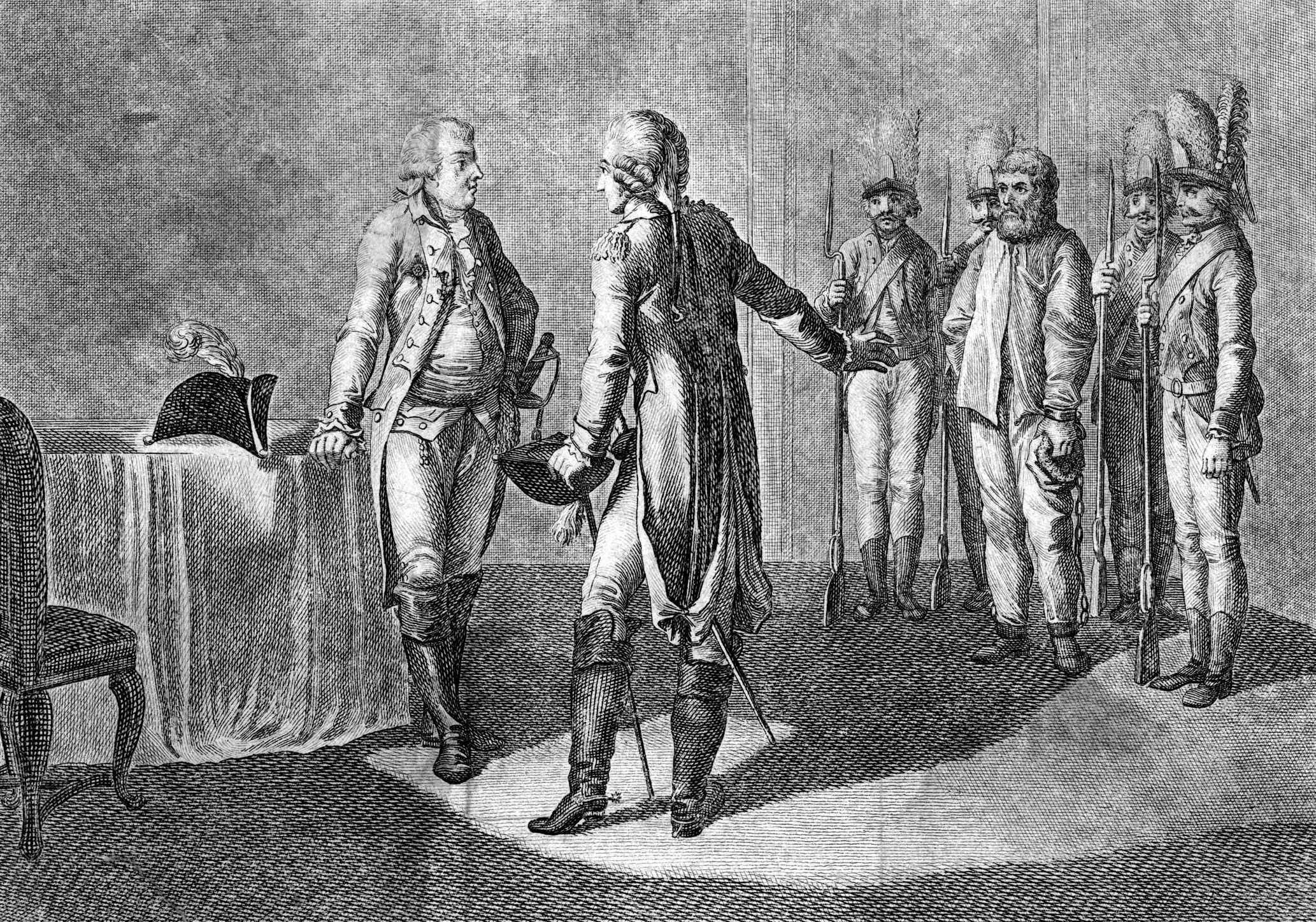

By that time, there was a greatly increased price of 28,000 rubles on the Pretender’s head, and after their final defeat by Mikhelson’s troops, Pugachev’s chief lieutenants decided that it was time to turn in the “czar” and save their own necks. Pugachev was captured while attempting to flee into the Ural Mountains and was taken before Count Panin, who slapped his face and exclaimed, “How dare a thief like you call yourself czar!” Perhaps the cruelest blow of all for the Pretender was the fact that Panin did not even realize that Pugachev had once served under his own command.

For his part, Pugachev was contrite, claiming that he had merely been the pawn of his unfaithful lieutenants who had fomented the rebellion: “God has been pleased to punish Russia through my sinfulness,” he told his captors. “I am guilty before God and Her Imperial Majesty.” Sent to Moscow in an iron cage aboard a cart, Pugachev arrived in the capital on November 4, 1774. Despite his fall from grace and power, he was still a celebrity. Sixty years later, Pushkin recalled parents telling their children at the time: “Remember that you saw Pugachev.”

On the morning of December 30, 1774, his trial began before 29 judges in the Throne Room of the Kremlin, which in Communist times would become the Great Hall of the People (dead dictator Josef Stalin lay in state there in March 1953). Pugachev’s death sentence was a foregone conclusion. It was duly carried out on January 10, 1775. By all accounts, Pugachev went to his execution bravely, bowing low in all directions. He was decapitated, drawn and quartered—a stark warning to all opponents of the empress.

In the aftermath of Pugachevshchina, Catherine sent Prince Potemkin to re-form the Cossacks into 10 formally organized regiments. The name Yaik was abolished forever, replaced by the word Ural. Pugachev’s home village was renamed for Prince Potemkin, and the empress decreed that the name of Pugachev should never be uttered or written again—an edict still in force under her grandson, Czar Nicholas I, when Pushkin began writing his 1836 novel of the rebellion, The Captain’s Daughter.

Pugachev’s revolt had a chilling effect on Russian life for years to come. The specter of a widespread peasant revolt caused Catherine to scrap further reforms, including the emancipation of serfs. It was an ironic aftereffect of the rebellion, which had hoped to accomplish precisely that feat. Nevertheless, Pugachev passed into history as a semifictitious hero of sorts. As an old inhabitant of Berda told a visiting official, “It may be Pugachev for some people, your honor, but for me he’s our Father, Czar Peter Federov.” A generation later, Russian Nihilists would nickname themselves “Pugachevs of the University” in sardonic tribute to the illiterate leader.

In 1959, Italian director Alberto Lattuada came out with a major motion picture about Pugachev’s rebellion, La Tempesta, starring Swedish actress Vivica Lindfors as Empress Catherine and American actor Van Heflin as Emelian Pugachev. It bombed at the box office—which is the opposite of what happened to Pugachev two centuries earlier.

A 1959 film, the Tempest, was a western telling of the story. Of somewhat questionable accuracy in some areas, it did present a picture of the times and the always interesting Russian machinations of power and intrigue.