By John Walker

After the disastrous Battle of Dunbar in April 1296, the Scottish revolt against England stalled for more than a year until a rebel force led by Andrew de Moray and William Wallace rekindled the flames of rebellion with a stunning victory over the English at Stirling Bridge. The impact of that battle induced King Edward I, known as “Longshanks” for his extraordinary height, to return from France to deal with the fractious Scots. After assembling a huge army, Edward marched north on his second invasion of Scotland in two years.

Dubbed the English Justinian because of his legal codes, which initiated significant changes to feudal law, strengthening both the crown and Parliament to the detriment of the old nobility, Edward was first and foremost a warrior king. His combat expertise, and that of his war machine, lay in campaigning. On campaign, in Wales, Scotland, southern France, and his native England, Edward had an innate ability to assemble an army and hold it together in the field. He was a man of stern character, jealous of his honor but true to his word only when it suited his end. His conduct toward the Welsh and Scots was marked by cunning, duplicity, and ruthlessness.

The Successor to Edward the Confessor

Born in June 1239 at Westminster, Edward was named after England’s last Anglo-Saxon king, Edward the Confessor. At the age of 15 he traveled to Spain for an arranged marriage to 13-year-old Eleanor of Castile. The marriage was a political union, its purpose to protect the southern borders of Gascony, England’s last possession in France. Edward was invested as the duke of Gascony and acknowledged his fealty to the French king, Louis IX. The governorship of Gascony previously had been in the hands of Simon de Montfort, whose autocratic rule had caused considerable unrest. Edward’s command of the duchy was just as turbulent; he ruled with a strong hand and was not averse to inflicting severe retribution on any subjects who challenged his authority.

Edward’s first experience in warfare came during uprisings in Wales in 1256. He supported his father in the baronial war that erupted in 1264, but Edward’s youthful rashness led to his capture alongside his father at the Battle of Lewes; he escaped a year later. In August 1265, he routed and killed de Montfort at the bloody Battle of Evesham. Five years later, Edward left England to join Louis IX on crusade; they were among the last true crusaders in the medieval tradition of seeking to recover the Holy Land. After the sudden death of Louis IX, the French forces broke off the campaign. Edward pressed on, but the size of his small force limited him to the relief of the city of Acre from the sultan of Egypt. On the crusade, Edward was badly wounded by a poisoned dagger wielded by a Muslim Shi’ite assassin; legend has it that his wife sucked the poison from the wound. Edward left the Middle East in late 1272, never to return.

Focusing His Attention on Scotland

Edward was returning to Europe when his father died in November 1272. Although he was absent, the people of England declared Edward their next monarch. Edward finally arrived in London in August 1274 and was crowned king at the age of 35. Determined to enforce the crown’s primacy in the British Isles, Edward spent the first part of his reign subjugating Wales. After Welsh leader Llywelyn ap Gruffydd refused to pay homage to Edward, the king raised an army and led a successful campaign against the Welsh prince in 1276-1277; the defeated Llywelyn was stripped of almost all his territory. Llywelyn’s brother, Dafydd, started another rebellion in 1282 and joined his brother in a war of national liberation. Edward responded quickly and decisively. Llywelyn was killed in December 1282 and Welsh resistance all but collapsed. Wales was incorporated into England in 1284 and Edward invested his eldest son and heir, Edward of Caernarfon, Prince of Wales in 1301. To consolidate his conquest, Edward constructed a string of massive stone castles encircling the new principality.

After a lengthy stay in his duchy of Gascony, Edward returned to England and focused his attention on affairs in Scotland. He had planned to marry off his son to the Scottish heiress Margaret, but when she died in 1290 with no clear successor to the throne, Scottish guardians invited Edward to arbitrate. To the surprise and consternation of the Scottish regents, Edward insisted that he be recognized as overlord of Scotland. After weeks of machinations, Edward’s precondition was accepted by the Scots—with the proviso that Edward’s overlordship would be temporary. Edward then proceeded to decide who should become the new Scottish king. After lengthy debate, he ruled in favor of John Balliol in November 1292.

Edward’s First Invasion of Scotland

In the weeks after Balliol’s coronation at Scone, however, Edward made it clear that he had no intention of dropping his claim to be Scotland’s superior lord. Edward forced Balliol to sign documents freeing the English monarch from his earlier promises. Edward’s constant demands for money, goods, and men were deeply resented by the Scots. When the king insisted that the Scots participate in his ongoing war with France, Balliol and the Scottish magnates had had enough. Balliol renounced his homage to Edward in 1295 and signed a treaty with Edward’s bitter enemy, King Philip IV of France. The Scots readied themselves for war with England. Fighting began in March 1296 when a Scottish force crossed the border and tried unsuccessfully to take Carlisle. A few days later, Edward launched his first invasion of Scotland at the head of a massive Anglo-Norman army. The English army, consisting of thousands of armored knights and Welsh archers, arrived outside the Scottish border town of Berwick-upon-Tweed to find the citizens prepared for a long siege. After Edward’s surrender demand was refused and he and his soldiers were taunted from the battlements, the English attacked and captured the town, brutally executing the castle’s 8,000 defenders in a retributive bloodbath.

After the Berwick triumph, Edward sent his most senior lieutenant, John de Warrenne, Earl of Surrey, to take Dunbar. De Warrenne arrived on April 29 to find its castle also prepared for a siege and the main Scottish army, commanded by John “Red” Comyn, Earl of Buchan, camped outside the castle walls. De Warrenne ignored the castle and concentrated on the main body of Scottish troops. The Scots, while not lacking in courage, were ill disciplined. Enflamed with battle fire, they broke ranks and hurled themselves at the smaller English army, only to be showered by thousands of Welsh arrows. Broken and confused, the survivors were trampled to the ground by de Warrenne’s cavalry, which rode pitilessly among the Scots wielding swords, lances, axes, and maces. The Scottish forces were routed with the loss of over 6,000 men; three Scottish earls and more than a hundred of Comyn’s lords and knights were captured and sent to London in chains.

Ruling Scotland Like a Province

Edward followed the victory at Dunbar with a triumphant march north through Scotland, taking Roxburgh and Edinburgh castles and advancing as far inland as Elgin. On his return south, the implacable English king confiscated the sacred Scottish coronation stone, the Stone of Scone, carting it from Perth to London. Balliol, deprived of his crown and other royal regalia, abdicated in July and was imprisoned in the Tower of London, where he and some 1,800 Scottish nobles were required to swear formal homage to Edward. The English monarch established a series of military garrisons in the north and proceeded to rule Scotland like a province.

Soon the fires of insurrection flared once more. The second phase of the war, involving the campaigns of William Wallace, began in early 1297. Wallace, the son of a minor local landowner and knight from Ellersie, quickly became a symbol of Scottish resistance to the English occupation of their homeland. By the spring of 1297, the whole of Scotland, with the exception of Lothian (long an Anglo-Saxon area) was in a state of armed insurrection. Wallace’s initial successes encouraged several Scottish nobles to join the rebellion, including William Douglas, James Stewart, and Andrew de Moray, who was in the north raising forces much as Wallace was doing in the lowlands. Wallace and de Moray became friends, organizing an army of commoners and small landowners in the predominantly Anglo-Norman lowlands and attacking English garrisons between the Forth and Tay Rivers.

Marching Through the Scottish Lowlands

Edward I, his hands full in France, ordered de Warrenne and the reviled Hugh de Cressingham, the king’s treasurer in Scotland, to suppress all resistance. The two English commanders marched through the southern lowlands with an army numbering between 15,000 and 20,000 men, including many mounted knights. As the English army of heavy cavalry, Welsh archers, and infantry marched toward Stirling castle in September 1297, Wallace moved rapidly to intercept them. On the banks of the Forth River, the English troops came within sight of Wallace’s and de Moray’s rebels arrayed on the opposite bank.

Wallace and de Moray had deployed their men on the high ground above a bridge that crossed the Forth north of Stirling. Meanwhile, de Warrenne, overconfident after Dunbar and believing that he was facing mere rabble, unwisely sent his mounted knights advancing across the narrow wooden bridge. The bridge was so narrow that only two men abreast could cross at the same time, but the English commanders ordered all the English horse and most of the foot across the bridge in the face of the Scottish enemy, ignoring a nearby ford that was broad enough for 60 horsemen to cross at a time. When the vanguard of the English forces, 5,400 English and Welsh infantry and several hundred cavalry, had crossed the bridge, Wallace ordered his foot soldiers forward. Seeing this movement, the heavily mailed English knights mounted a furious charge up the slope toward Wallace’s infantry. Scottish archers began a steady fire, causing the English forces to waver and recoil.

Pressing on Toward the Bridge

Wallace’s foot soldiers pressed their downhill charge toward the bridge while de Moray executed a superb tactical movement, getting his men between the bridge and those English soldiers who had already crossed over, effectively cutting off their retreat. As confusion set in among the English ranks, discipline was lost. Wallace pressed on with greater force; the half-formed English infantry columns gave way and many heavily armed English knights were driven into the river and drowned. De Warrenne attempted to turn the tide by sending his remaining reinforcements across the bridge. After the better part of the force made the crossing, they were assailed on all sides by Scottish spearmen, adding to the confusion and slaughter.

Before the rest of de Warrenne’s reinforcements made it all the way across the bridge, the span collapsed and crashed into the river. This mishap proved catastrophic for the English when a body of Scottish infantry forded the river downstream and fell upon the English rear, ensuring victory for the Scots. A large number of English were drowned attempting to re-cross the stream. After making a last attempt to rally his beaten soldiers, de Warrenne fled to Berwick, sending news of the disaster to Edward. Some 5,000 English infantry and 100 knights had been killed, and the huge English baggage train was lost; the Scottish dead numbered in the hundreds. Among the English casualties was Cressingham, whose body was flayed and cut into strips. Wallace reportedly used a swatch of Cressingham’s skin to make a shoulder strap for his sword. Unfortunately for the Scots, de Moray was mortally wounded in the battle and died a few weeks later.

“Guardian of the Realm of Scotland”

Wallace was knighted and appointed “Guardian of the Realm of Scotland.” After the phenomenal success of Stirling Bridge, he waged a campaign of guerrilla warfare for the remainder of the year, retaking Berwick, plundering Northumberland, and ravaging the northern English countryside. At the same time, he attempted to restore trade between Scotland and Europe, which had been interrupted by English efforts to isolate the Scots.

Edward was campaigning in Flanders when he received news of the Stirling Bridge defeat. After reaching a hasty peace agreement with Philip IV, he returned to England in March 1298 and set about raising a huge army from all corners of his domain to subjugate the stubborn Scots. He transferred his headquarters to York and took the rare step of releasing 300 prison inmates, promising them pardons in return for their enlistment. Crossbowmen from Gascony and Welsh archers were also recruited, along with foot soldiers from Ireland. The men of southern Wales generally carried spears, but the northern tribesmen possessed a formidable new weapon: the longbow. In the hands of a trained archer, it was an extremely effective weapon, hitting targets with such force that a shaft could pierce chain mail and pin a knight to his horse. A skilled bowman could keep five arrows airborne at once.

The Largest Invasion Force to Enter Scotland Since Rome

The army Edward assembled at York was the largest invasion force to enter Scotland since the Roman general Agricola conquered Britain in the first century ad; it consisted of 2,500 heavily armored and splendidly mounted knights and some 13,000 Welsh and English infantry. Eight earls had joined Edward, each bringing along his own large contingent of knights and infantry, swelling Edward’s ranks by several thousand men. Many of the cavalrymen, veterans of the French and Welsh campaigns, rode horses completely armored from head to hindquarters. In addition, there were 500 Life Guards from Gascony.

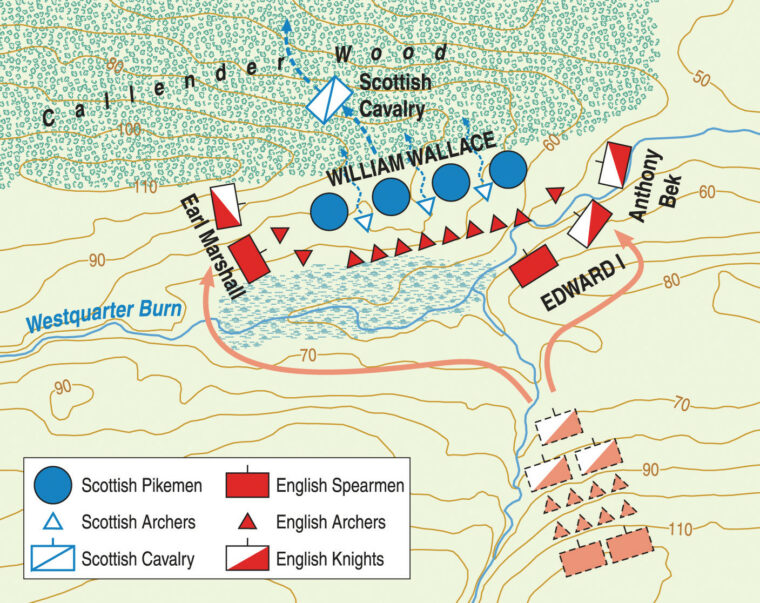

Wallace, in turn, commanded a resolute force of between 8,000 and 10,000 men. Wallace eventually moved his army to Falkirk, in west Lothian, where he chose a strong position with a swamp in his front that was almost impassable for cavalry and his flanks guarded by heavy woods and rough terrain. Outnumbered by Edward’s multinational force, Wallace hid his army in the Callander Wood south of Falkirk and waited for opportunities to harass the English forces arrayed against him.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments