By Sam McGowan

Common wisdom has long held that Japanese pilots and aircraft, particularly their fighters, were superior to the American, Australian, and British counterparts they faced in combat in the Philippines and Southeast Asia in the opening months of U.S. involvement in World War II.

While it is true that some Japanese fighters, particularly the famous Mitsubishi-built Zeros, had achieved considerable success in China, they were not actually superior airplanes. These Japanese fighters were highly maneuverable and had superior high-altitude performance because of their lighter weight, but U.S. Army Air Corps pilots in the Philippines quickly learned that American fighters could more than hold their own in combat when their best features were exploited.

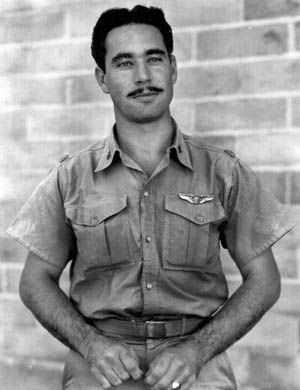

One pilot who made use of his background in aeronautical engineering to completely master the Curtiss P-40 Tomahawk was Lt. Col. Boyd David Wagner, commander of the 17th Pursuit Squadron based at Nichols Field near Manila. Wagner became America’s first ace since World War I.

“Buzz” the Pilot from Nanty Glo

Boyd Wagner was a Pennsylvanian who hailed from a small town with the rather unique name of Nanty Glo. He graduated from Nanty Glo High School in 1934 then enrolled at the University of Pittsburgh as an engineering student. His major was in aeronautical engineering, but he left his university studies to join the Army after three years. Even though he was not awarded a degree, his knowledge of aeronautical engineering far surpassed the typical fighter pilot’s of his day and led to his becoming America’s first World War II ace.

Upon completion of the aviation cadet program at Randolph Field, Texas, in 1938, he was commissioned as a second lieutenant and assigned to a fighter squadron, reportedly the 27th Pursuit Squadron that was based at Selfridge Field, Michigan, not far from Detroit. Wagner quickly gained a reputation as an extremely skilled pilot and picked up the nickname “Buzz,” although there are conflicting accounts as to the reason for the nickname. At the time of his death, a Time magazine article quoted other pilots as saying he was so good he “could take the camouflage off the roof of a hangar.” Other sources attribute the nickname to his habit of “buzzing” unsuspecting aircraft—including commercial airliners—that he came across while out on training missions. Regardless, there is no doubt that Boyd Wagner was a highly accomplished pilot who could fly the wings off a fighter at both treetop level and higher altitudes.

Deploying to the Philippines

By December 1940, Wagner had transferred from the 27th Pursuit to the 17th Pursuit. And when the latter was assigned to the Philippines, Wagner went along. At the time, the squadron was equipped with Seversky P-35s and Boeing P-26s which, while they were first-line fighters of the day, were already obsolete when compared to combat aircraft being produced by the Germans and Japanese.

The arrival of the 17th Pursuit to the Army’s Philippines Department brought U.S. fighter strength up to three squadrons. All were assigned to the 4th Composite Group, which included a bomber squadron (flying antiquated Martin B-10s) and an observation squadron. In May 1941, six months after the 17th Pursuit arrived in Manila, the squadron’s commander, Major J.K. Gregg, took command of the 4th Composite Group. The new 17th Pursuit Squadron commander was none other than First Lieutenant Boyd D. Wagner.

Wagner assumed command of the squadron as all of its P-26s were being replaced with P-35s, which had been diverted to the Philippines from a planned sale to Sweden. As they were replaced, the P-26s went to the Philippines Air Force.

Shortly after Wagner took command of the squadron, the 17th Pursuit was moved to the tiny airfield at Iba, a grass strip on the western beach of Luzon just west of the Zambales Mountains. The Air Corps had established a gunnery range in the mountains, and the 17th’s assignment at Iba was for gunnery practice. Iba was a remote location, and the airfield was primitive at best. Transportation between the field and the Army Air Corps fields at Clark and Manila was poor. The pilots discovered that their guns were largely defective because of improper installation and adjustment. Every gun in the squadron had to be removed from its mountings and adjusted, and the mountings repaired. Faulty gun installations and operation would plague the fighter force when war finally came.

Wagner’s assumption of command of the 17th Pursuit came as the United States was beginning to beef up the Philippines Department in response to Japanese aggression in China. Previously, the Philippines had been seen as a backwater command and had been essentially written off in U.S. military defense plans for the Pacific. But the rise of Japanese imperialism, particularly in China, caused President Franklin Roosevelt to reconsider U.S. options and to begin a military buildup in the Philippine Islands.

The plan was to establish a large bomber force consisting of Boeing B-17s and Consolidated B-24s, which were just entering the U.S. Air Corps inventory. They would serve as the main deterrent to Japanese aggression in the region, with several pursuit squadrons to serve as interceptors. A new pursuit command was established at Nielson Field with Colonel Harold George, who had recently arrived in Manila, as the commander.

The new importance of the Philippines led to the decision to equip the pursuit squadrons based there with the latest fighter plane, the Curtiss P-40. The first models began arriving in the islands in June and were given to the 20th Pursuit Squadron at Clark Field. Later models were already rolling off of the Curtiss production lines and were destined for the Philippines, but would not arrive until October.

In September, the 19th Bombardment Group transferred to the Philippines and took up residence at Clark Field. To make room for the B-17s, Wagner took his 17th Pursuit Squadron south to Nichols Field, where the squadron had previously been based.

A new organization, the 24th Pursuit Group, was activated to control the three pursuit squadrons. In October, the first complement of new P-40Es arrived and the 3rd and 17th Pursuit Squadrons began replacing their P-35s with the newer and more capable fighters. Two additional squadrons, the 21st and 34th Pursuit Squadrons, left California in early November by ship to join the 24th Pursuit Group. The 21st joined the 17th at Nichols Field and was commanded by First Lieutenant William E. Dyess. Since Dyess and Wagner were both members of the pilot training programs at Kelly and Randolph Fields at San Antonio, Texas, at about the same time, it is possible that they already knew each other. Regardless, they quickly became friends at Nichols.

A Shipment of P-40Es

On December 6, Colonel George met with the young pilots at Nichols Field and advised them of the impending conflict with Japan. It was a somber meeting. George pulled no punches with the young pilots as he outlined their situation. A communiqué had gone out from the White House through the War Department the previous week that warned General Douglas MacArthur, who was in command of U.S. forces in the Philippines, that war with Japan was imminent.

George knew that if war came his young pilots would be facing overwhelming odds. He advised that while their situation was not suicidal, it was nearly desperate because they would be facing an enemy with comparatively shorter supply lines and far superior numbers. Yet, even he did not imagine just how severe the situation was going to be. A shipment of new P-40Es that had arrived at the depot some time before had been assembled and were replacing the P-35s that the men of the 21st had been given temporarily upon their arrival, and operational fighter strength was at 70 airplanes.

George told the fighter pilots that they would be able to make a good showing. All of the pursuit squadrons were on full alert, and had been since the message from Washington reached Manila advising that war was imminent. Nearly every morning the two squadrons at Nichols were alerted, and the pilots had taken to sleeping by their airplanes. Several reports of unknown aircraft over or near the Philippines had come in, and pursuit planes had gone up in attempts at interception.

While the number of operational airplanes George reported was accurate, the total was actually misleading. Ed Dyess’s 21st Pursuit Squadron was just receiving its complement of new P-40Es, and none of the airplanes were truly combat-ready. Fresh from the factory, none of their engines had been broken in, or “slow-timed,” and their guns had to be bore-sighted.

Hearing Word from Pearl Harbor

Wagner’s squadron was operationally ready and would account for many of the Japanese aircraft that fell to American fighters during the opening days of the Pacific War.

The lieutenant led the first Air Corps attempted interception of the Japanese. Starting on December 2, a single unidentified airplane flew over Clark Field just before daybreak four nights in a row. No origin for the unidentified airplane could be found, and after it came over the second time on December 3, orders were given to intercept and force the airplane down. If the pilot committed any overt act, the airplane was to be shot down. On the night of December 4, Wagner took a flight of six P-40s from his squadron aloft, but their search was fruitless, largely because of the lack of an adequate air to ground communications system. A similar interception attempt by the 20th Pursuit Squadron the following night was also unsuccessful as the unidentified airplane again overflew Clark without being disturbed.

At 2:30 am on December 8, the pilots of the 17th and 21st Squadrons were alerted and told to man their airplanes. It was the sixth successive day that they had been alerted. After about 10 minutes they were told to stand down. At about 4:30 am the telephone in Ed Dyess’s orderly room rang, and he received the first word of the attack on Pearl Harbor, which had taken place about two and a half hours before. Wagner was no doubt notified at the same time.

Word of the attack spread quickly through the quarters, and the pilots soon were back at their airplanes, and either gathered in groups on the flight line or tried to get more sleep on the wings of their fighters. At 8 am, Wagner was ordered to take his 17th Pursuit Squadron aloft and to set up an air cover over Clark Field. Wagner set up a patrol line just north of Clark near the town of Tarlac. The 20th Pursuit, which was based at Clark, had taken up a line farther north near the town of Rosales to defend against a formation of Japanese bombers that had been reported north of Luzon. The 19th Bombardment Group’s Boeing B-17s began taking off at 8 am to avoid being caught on the ground. Two of the 19th’s squadrons were no longer at Clark. They had moved south to Del Monte Field on Mindanao a few days before.

As it turned out, the approaching Japanese bombers turned and attacked Baguio, a mountain town on northern Luzon. Wagner led his men back to Clark, where they were refueled and ready to go by 11 am. At about 11:30 Wagner was ordered to take his squadron back into the air. A formation of enemy aircraft was reported to be headed toward Manila, so he was instructed to patrol over Manila Bay and the Bataan Peninsula.

Japan’s Opening Strikes

The first Japanese attack came on the airfield at Iba, where the only operational radar station in the Philippines was destroyed, and on Clark Field, where the destruction was severe. The B-17s had been recalled to refuel and re-arm for an attack on Formosa, and the 20th Pursuit’s P-40s were refueling after their unproductive mission that morning. The fighters were lined up in preparation to take off when Japanese bombs began falling on Clark. A few fighters on takeoff roll managed to get off the ground, but most of the P-40s were hit by shrapnel from exploding bombs.

A strafing attack by Japanese fighters destroyed or severely damaged all but three of the B-17s (all three of those, in turn, were destroyed in accidents caused by poor visibility over the next couple of days). The pursuit force fared far better than the bombers. Except for the ones that were on the ground at Clark when the attack came, only a handful fell victim to Japanese guns. Nevertheless, a number were lost due to engine failure or to crash landings.

Because of the 17th’s station well south of Clark, it was not involved in the hostilities on the opening day of the war. Late in the day, Wagner and Dyess were ordered to take their squadrons to Clark under the assumption that Nichols Field, which had been spared attack, would be the next target. As it turned out, the 17th ended up at Del Carmen, the secondary base, because the dust over Clark caused such a melee among the arriving 21st fighters that it was nearly dark by the time the last one landed. Only one 17th fighter landed at Clark and then only because the pilot’s radio had gone out and he had failed to get the word to divert to Del Carmen.

The order to reposition the two squadrons was timely—at about 3 am on December 9 Japanese bombers struck Nichols Field and caused considerable damage. As the Japanese bombers approached Manila, a flight of four P-40s was ordered into the air, but one crashed on takeoff and slid into another fighter, destroying them both. The other three patrolled over Manila but did not make contact with the Japanese attackers.

Engagement at Cavite

December 10, the third day of the war, was a red-letter day in the air battle for the Philippines. That morning the 17th Pursuit Squadron was assigned to fly top cover for a flight of B-17s sent to attack the Japanese invasion fleet, which had taken up station off of Vigan on Lingayen Gulf. Led by the 17th, the P-40s dropped down with a devastating strafing attack on the Japanese landing barges and effectively broke up the invasion, although the results were temporary.

That afternoon the 17th and 21st Squadrons were sent up against Japanese bombers escorted by fighters that attacked the naval base at Cavite. Although the Navy claimed later that no American fighters were present, they were there in force, but only a handful were able to penetrate the Japanese fighter screen and attack the bombers. Many of the P-40s had been launched almost an hour before the attack when Japanese aircraft attacked Del Carmen. They were hampered by having been aloft for some time before the action began, and even though they put on a good showing at the beginning of the air battle, they began running out of gasoline.

The pilots knew of their fuel problem before the battle but decided to attack and try to do as much damage as possible to the Japanese before their fuel ran out. An intense battle ensued, and the action was so fierce that none of the American pilots put in any claims for aircraft destroyed because they were unable to see what happened to airplanes they shot at. The action lasted for about 15 minutes before the P-40s began running out of gasoline and had to break off. Three P-40 pilots were killed, and at least eight others either crash landed or bailed out of airplanes that had run out of fuel. Every airplane was damaged, but most crashed due to empty fuel tanks.

The air battle had begun with about 40 P-40s. By the end of the day the force had been substantially reduced. The fighters that did manage to limp back to their bases had all suffered varying degrees of battle damage that required repair before the fighters could be returned to service.

Japanese landing parties had come ashore at Vigan and Aparri, which created a need for aerial reconnaissance. With the fighter force dwindling away, MacArthur’s headquarters decided that the remaining airplanes should be used for reconnaissance. That night an order came down through Far East Air Force headquarters that the interception would cease. The order was met with resentment among the fighter pilots, who felt that they were just getting the measure of the Japanese forces.

On the morning of December 11 (possibly December 12), Wagner took off from Clark Field on a solo reconnaissance flight to Aparri, on the northern coast of Luzon. Although no mention of his actions of the previous day is recorded, it is probable that he had achieved his first two kills during the melee near Cavite.

Wagner flew this mission above the clouds for more than 200 miles, navigating entirely by dead reckoning. When he estimated that he was about 10 minutes from his destination, he let down through the clouds on instruments. When he broke out, he found himself right over two Japanese destroyers, which opened up with a barrage of anti-aircraft fire.

Wagner dropped down to within a few feet of the waves and turned inland. As he realized he was near the airport at Aparri, he suddenly saw tracers zipping past him from above and behind. He looked back and saw two Zeros behind him and three more above him. He immediately pulled up into a steep chandelle into the sun and lost the two pursuers, then did a half-roll and came down on them from behind. They were close together, and he shot them both down almost immediately. He looked down and saw the enemy airport directly beneath him, so he made two strafing passes on the dozen or so fighters he saw on the field and destroyed at least five. As he pulled up from the second pass, he saw that the three fighters he had seen above him were diving toward him.

By this time he had realized that the P-40 was considerably faster than the Zero, so he dropped his empty belly tank and shoved his throttle forward and quickly outdistanced the pursuing airplanes. His mission completed, he turned back toward Clark. The next day, a proud General Douglas MacArthur sent out a communiqué describing Wagner’s actions.

Victories at Cavite?

Wagner’s account of his victories, reported by some to be the first of many, sounds almost unbelievable when considering the awe with which so many writers have treated the Japanese fighter pilots in the early part of World War II. Until the invasions of the Philippines and Singapore, Japan’s finest had never fought modern first-line fighters or pilots with superior training. Its previous victories had been gained over China, against Chinese pilots with limited experience who were flying outdated airplanes.

While it is true that U.S. airpower in the Philippines had been severely depleted in the opening days of the war, the losses were due more to bad luck and bad timing than to the superior skill of the Japanese airmen.

Wagner was a superior and knowledgeable pilot who had quickly picked up on the weaknesses of the Japanese airmen and their aircraft, and he knew how to exploit them. P-40s were armed with six .50-caliber machine guns that could throw out a hail of lead. They caused the rather flimsy Japanese fighters to come apart if they were caught in the apex of fire. In the coming weeks and months, Wagner would prove time and time again that his first recorded kills were no fluke.

Wagner’s actions on December 11 were not his first. He and Ed Dyess were eating lunch at Clark Field after a morning mission on December 10 when they were alerted to take to the air. They took off in a cloud of dust that was so thick they could not see each other. When they broke out of the overcast, the two squadron commanders were astonished that they had climbed through the dust clouds with their wingtips only inches apart!

Dyess had problems with his guns and had to land at an outlying field on the way to Manila, but Wagner evidently continued on and no doubt was engaged in combat.

The events of December 10 are somewhat confusing, as some authors have reported that the P-40s did not shoot down any Japanese airplanes while others recorded that they did. Noted aviation author Martin Caidin claimed that the P-40s were unable to penetrate the enemy fighter screen and attack the bombers, but does not mention that the P-40s shot down several Japanese fighters. Walter Edmonds, on the other hand, stated that there was a tremendous air battle until the P-40s started running out of fuel and began disengaging, and that more Japanese aircraft were shot down than American. Apparently the 17th was heavily engaged in the action, so it may be that this was when Wagner actually got his first two kills, not on the December 11 mission as is commonly reported.

Heroism at Vigan

On December 16, Wagner was part of one of the most heroic missions of the war. Reconnaissance had revealed that Japanese aircraft were operating from an airfield just inland from the beach at Vigan, and Wagner’s squadron was given the mission of destroying them. He picked Lieutenants Russell Church and Allison Straus to go with him on the mission. The Americans had taken off before dawn and began their attack on the airfield in the light of the breaking day while the Japanese pilots were just rising from their night’s sleep. When they reached the vicinity of Vigan, Straus stayed aloft to keep watch for attacking aircraft, and Wagner went down with Church on his wing to strafe the airfield. Each fighter carried six 30-pound fragmentation bombs in addition to its six .50-caliber guns. Wagner counted 25 Japanese aircraft lined up alongside the landing strip. He made his first pass without taking a single hit, but Church was not so fortunate. Alerted by Wagner’s pass, every antiaircraft gun on the airfield concentrated on Church’s fighter and set it on fire just as he was beginning his dive. He could have pulled up and away from the target and gained altitude to bail out, but he elected to continue his run. He dove the burning airplane on the airstrip and dropped his bombs, then continued down the line in a strafing pass. He never altered his course, and the burning airplane continued on a straight line to crash in a flat field about a mile past the airfield.

Church’s heroic death struck a chord in Wagner: Even with heavy antiaircraft fire rising up from around the airfield, he nevertheless made five strafing passes.

A single Japanese fighter got airborne, but Wagner throttled back and let it pass him, then shot it out of the sky. When the fighter first took off, Wagner could not see it because it was below him, so he rolled his P-40 upside down to get a better view. When he saw the Japanese plane beneath him, he flipped upright and throttled back. It was an amazing piece of airmanship.

There is some question as to Straus’s actions, or whether he was even part of the mission. Although the 24th Pursuit Group records had him on the mission and taking part in the strafing, no mention is made of him in the recommendations for the Distinguished Service Crosses that were awarded to Wagner and Church. Church was reportedly recommended for the Medal of Honor, probably by Wagner since he was an eyewitness and the squadron commander, but the recommendation was evidently downgraded. The Japanese buried Church’s body with full military honors.

Counting Kills

Several accounts show that Wagner became an ace with the shooting down of the lone fighter at Vigan. One source claims that he actually shot down four fighters over Aparri. However, Wagner himself made no such claim in an interview he later gave to Life magazine reporter Carl Maydans. He mentioned only the two that jumped him as he came over the shore after breaking out of the overcast.

Edmonds mentions only the two fighters over Aparri in his highly acclaimed work, They Fought with What They Had. The Air Force officially credits him with becoming an ace on December 17 (U.S. time, December 16 Philippine time). If he only shot down two fighters over Aparri, then he must have reported two victories the day before in the big melee over Manila, but was erroneously credited for four the following day. The 24th Pursuit Group’s records were written long after the fact and are not as accurate as they would have been had they been written at the time of the action.

Interestingly, not all of the fighter pilots who shot down Japanese aircraft were given credit for their kills. Ed Dyess, for example, is known to have shot down at least three Japanese aircraft but was never credited with any, probably because his squadron remained on Bataan, and the pilots became prisoners of war.

Leaving the Philippines

Sometime in December, Wagner was wounded. Details and even the exact date are not known, although the citation for the Purple Heart he was awarded shows that the incident took place on December 18. The 24th Pursuit Group history shows the date as being December 22. Wagner was certainly wounded during one of two attacks against the Japanese beachheads on Lingayen Gulf where they were making their main invasion.

Wagner was wounded when a 20mm shell burst on his canopy and showered him with pieces of Plexiglas. One piece entered his eye. He made it to safety, but the wound kept him out of the cockpit for some time.

Meanwhile, a few days before Christmas, General Henry “Hap” Arnold, the senior air officer in the U.S. Army, ordered the headquarters of the Far East Air Force out of the Philippines to Australia. The War Department was taking steps to carry out orders from President Roosevelt to effectively abandon the Philippines and establish a new Allied headquarters in Australia.

In late December Wagner and eight of his pilots were ordered out of Luzon to Australia, where they would form a new fighter squadron with the P-40s that had been diverted there.

The pilots of the 17th Pursuit Squadron were part of a contingent of combat pilots that Colonel Harold George sent to Australia. The first of the fighter pilots departed Neilson Field on December 31; a second group left two days later from Bataan on January 2, 1942. Wagner was one of the men who departed on the latter date. The transport flew across Bataan at treetop altitude to avoid detection by Japanese fighters and made its way to Mindanao where the pilots spent several days working on the worn-out transport. They eventually landed at an airfield in Borneo but were unable to continue the flight because the right engine failed completely. A Navy PBY Catalina flying boat was sent to pick them up and take them to Java. They eventually made their way on to Australia where they joined the seven pilots who had come out ahead of them.

Disaster at Java

Although Wagner had commanded the 17th Pursuit at Nichols Field, he was outranked by Captain Charles Sprague, who had formerly been a member of Colonel George’s staff at V Interceptor Command. It has been reported that when a new provisional pursuit squadron was formed with 17 (one of the fighters had been shipped without a rudder) of the 18 P-40s, Wagner and Sprague flipped a coin to see who would be in command.

Regardless of whether the legend is true, Sprague became commander of the newly organized 17th Pursuit Squadron. Sprague was authorized to pick any pilots he wished, except for Wagner, Captain Grant Mahoney, who was another Philippines legend, and two other pilots, all of whom were being held back by Far East Air Force to take command of new squadrons as they were organized. The pilots believed they were headed back to the Philippines, but when they reached Darwin, they learned that they were going to Java, where the Japanese had mounted an offensive.

Unfortunately, Sprague was lost in Java, as were all of the P-40s. They were turned over to the Dutch as it became apparent that the Japanese would prevail. A shipment of 32 P-40s that was on the way to Java aboard the old aircraft carrier USS Langley was also lost. Another shipment of 27 fighters reached Java on another ship but were still in their crates when the Allies abandoned the islands.

Director of Intercept for the Port Moresby Area

Wagner remained behind in Australia and, fortunately, missed the debacle in Java. He and four other pilots from the Philippines were placed in charge of training newly arriving pilots who came in from the States. He was put in command of the new 13th Pursuit Squadron (Provisional) but was soon moved to V Interceptor Command headquarters. After this assignment, Wagner was quickly promoted and by April was a lieutenant colonel. During that month, reorganization led to the establishment of the Army Air Forces as the air combat element of the Army, while the Air Corps remained as the training element. The pursuit designation was changed to fighter.

In late April 1942, Wagner took two squadrons from the 8th Fighter Group (flying Bell P-39 Airacobras) north to Port Moresby, New Guinea, to relieve the Australian P-40 squadrons that had been operating from there. Wagner’s new position was officially Director of Intercept for the Port Moresby area; his promotion reportedly made him the youngest lieutenant colonel in the Army. As soon as the pilots entered combat they began racking up a remarkable record that made them one of the most successful units in Air Force history. As Wagner had done with the P-40, he thoroughly familiarized himself with the P-39 and knew it inside and out. Although it was not capable of high-altitude combat, he considered it to be an effective fighter against bombers up to 18,000 feet and against fighters at lower altitudes. The P-39 lacked in acceleration in comparison to the famed Zero, but it was actually faster in level flight and could pull away from the Japanese fighter after its initial burst of power.

On the afternoon of April 30, shortly after they arrived in Port Moresby, Wagner led 13 P-39s on a strafing attack on the Japanese airfields at Lae and Salamaua. The results were spectacular, and in the brief air engagement that followed the P-39s shot down four Japanese Zeros. Three of the enemy aircraft were claimed by Wagner himself, which brought his total score to eight confirmed kills, a record that would stand for some time. Wagner evidently picked up another piece of Plexiglas in his eye, which ended his combat flying.

Over the next several months Wagner’s fighters proved more than equal to the task of defending Port Moresby even though they were flying an airplane that was considerably inferior to the Zero in overall performance. What the tiny P-39s lacked in performance, they made up for in rugged construction and survivability. Wagner ordered his men not to attempt to dogfight with the Japanese, but to use the P-39’s superior speed to advantage and to attack from higher altitude in a single diving pass at an enemy formation. Because they lacked the performance to climb to high altitudes, the P-39s often failed to intercept approaching Japanese bomber formations. Consequently, none of the P-39/P-400 pilots achieved ace status while flying Airacobras.

Even though their air-to-air combat record was less than spectacular, the P-39s wreaked a heavy toll on Japanese air power in New Guinea. Recognizing that an airplane destroyed on the ground is the same as one shot down in aerial combat, Wagner sent his fighters out on regular strafing attacks on the Japanese airfields around Lae. Losses in terms of equipment were heavy, but in terms of men they were light. In nearly every case when a P-39 or P-400 went down, the pilot survived. The 39th Fighter Squadron claimed 12 enemy aircraft for a loss of nine of its own, but lost only one pilot who bailed out at high speed and struck the tail of his airplane. All of the other pilots who were shot down managed to bail out of their planes or crash land and survive.

Wagner’s leadership in New Guinea set the stage for the upcoming air war in the Southwest Pacific. Experience gained by the young pilots in the underpowered P-39s and P-40s paid dividends when they transitioned into the high-performance Lockheed P-38 Lightning beginning in late 1942. Wagner’s own combat experience came to an end when he returned from Port Moresby in June.

An Eternal Legacy

Lieutenant General George C. Kenney arrived in Australia in late July to assume the role of MacArthur’s “air boss,” and one of his first actions was to relieve the Philippines veterans and send them back to the States for a well-deserved rest. Wagner protested the transfer and requested that he be allowed to remain in the theater and in combat, but his protests fell on deaf ears. Kenney realized that the Philippines veterans were worn out both physically and emotionally and considered them to be more of a liability than an asset. In Wagner’s case, Kenney recognized that the fighter pilot’s knowledge of the Japanese aircraft would be more beneficial back in the United States helping with the design of new fighters.

After his return to the States, Wagner was assigned as an engineering liaison officer to the Curtiss Aircraft plant in Buffalo, New York, where the company produced P-40s. Why he was assigned to a plant that was producing airplanes that were due to be replaced by newer types is unclear, although in 1942 the P-40 was still considered to be a top-of-the-line fighter.

In his new capacity Wagner flew P-40s around the country to fighter bases and talked to pilots about the airplane’s capabilities in combat. On November 29, 1942, Wagner took off from Eglin Field, Florida, for Maxwell Field at Montgomery, Alabama. He never reached his destination, and when no word was heard from him a search was initiated. Swampy conditions made the search difficult. Six weeks later, in January 1943, the crash site was finally located some 25 miles from his takeoff point at Eglin Field.

No determination of the cause of the crash was ever made public. The wreckage was found with the nose of the airplane buried deep in the ground, an indication that it was in a near vertical attitude when it crashed. The impact was so severe that only part of Wagner’s remains were recovered. The wreckage was left in the Florida swamps.

Although Wagner’s life came to an abrupt end, as did the lives of so many of the heroes of the early Pacific War, his legacy lives on. The 8th Fighter Group that he took to Port Moresby went on to become one of the most productive fighter groups of the war, as did the 35th Fighter Group that followed it. As the top-scoring ace of the early months of the war, his record was a standard that challenged the new pilots who came in to replace him. His name will always be associated with the early war in the Philippines, and Boyd D. Wagner will always be remembered as America’s first World War II ace.

I have read that the gasoline supply on the Philippines had been contaminated, ruining engines and performance. There was no speculation at to how or by whom this contamination took place.

Did any of Chennault’s AVG end up flying in the P.I.?