By Patrick J. Chaisson

Lieutenant Commander Draper Kauffman was crawling across a moonlit beach on enemy-held Tinian Island when he first noticed the sound of voices. Kauffman was furious—how could one of his men be so careless as to jeopardize the entire team’s security when everything depended on silence and stealth.

The 32-year-old U.S. Navy officer was about to whisper a harsh warning to keep quiet when he realized the voices were Japanese. Kauffman gripped his sheath knife as an enemy patrol came toward him. Quickly slipping out of his swim trunks, he rolled in the sand to camouflage his body. All he could do now was pray the patrol didn’t see him.

Eleven years before this incident, Midshipman Draper L. Kauffman could never have imagined himself in command of the U.S. Navy’s toughest underwater demolition men as they scouted hostile beaches halfway around the world. He had just graduated from the United States Naval Academy, but Depression-era policies denied him a commission in the peacetime Regular Navy. As a cost-saving measure, only 50 percent of 1933’s graduating class at Annapolis would enter active duty. Weak eyes kept Draper from following his father—James L. Kauffman (USNA 1908)—into a Navy career.

Instead, Kauffman took a job with a New York-based steamship line and was assigned to the company’s Hamburg office, where he witnessed firsthand Adolf Hitler’s rise to power during the late 1930s. He developed a lasting hatred for the Nazi regime; these feelings only intensified after Germany invaded Poland in 1939.

Against his family’s wishes, Kauffman joined the American Volunteer Ambulance Corps as a driver in 1940. On May 10 of that year, he reported for duty with the French Army in Alsace-Lorraine—coincidentally, the same day that German forces launched their blitzkrieg campaign against Belgium, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands.

As fierce battles raged across the region, Kauffman spent the next five weeks evacuating the wounded under frequent enemy fire despite the Red Cross markings on his vehicle. For his selfless dedication to duty, he received the French Croix de Guerre.

In mid-June, Draper was captured by German troops and sent to a prisoner of war camp at Lunéville. He spent two months there before the U.S. Naval Attaché (a friend of the family) arranged his release. Kauffman then made his way to neutral Portugal and hopped a freighter bound for England. By September 1940, he was wearing the uniform of a sub-lieutenant in the Royal Navy Volunteer Reserve—the only American officer then serving with that organization.

While in the U.K., Draper volunteered for a hazardous assignment with the Royal Navy’s bomb disposal squads. Well aware of the risks, Kauffman felt he could best serve the Allied cause by deactivating unexploded munitions. His first mission took him to Liverpool, where he disarmed an aerial mine whose warhead was found resting on an overstuffed chair inside a private residence.

Kauffman defused dozens of German projectiles during his year with the Royal Navy. By 1941, the Germans were fitting aerial ordnance with devices that detonated the main charge if tampered with. In January, Draper’s hand slipped while working on an air mine—when its anti-withdrawal mechanism began buzzing, he dashed to safety before the warhead went off. The explosion left him dazed but otherwise unharmed.

In September 1941, Kauffman—now wearing the two stripes of a RNVR lieutenant—sailed for the States to enjoy a well-earned leave of absence. While in Washington, D.C., he briefed the Navy’s Chief of Ordnance, Rear Admiral William H.P. Blandy, on the Royal Navy’s bomb disposal program. He also met with Rear Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, Chief of Naval Personnel, regarding his future employment.

As Kauffman recalled, Nimitz opened by asking the lieutenant why he wasn’t in the U.S. Navy. “Sir,” Draper replied, “each time I write applying to our Naval Reserve, I get a letter back rejecting me because my eyes aren’t good enough.”

“They are now,” Nimitz said, concluding the interview.

Within days, Kauffman was released from the Royal Navy. On November 7, 1941, he accepted a commission with the rank of lieutenant, U.S. Naval Reserve, with his first assignment the establishment of a bomb disposal school in Washington D.C.’s Naval Gun Factory. His first task was to develop a curriculum, then find the right men to teach it. Ensign Means Johnston, Jr., an officer Kauffman described as “top-notch” in every regard, became his executive officer. Instructors included others with experience in the United Kingdom as unexploded ordnance technicians.

Kauffman’s initial class of 50 bomb disposal officers came primarily from the Naval Reserve commissioning programs at Northwestern and Columbia Universities. He sought students who possessed “self-confidence, self-discipline, and self-reliance;” tellingly, his volunteers also had to be unmarried. They would begin training after the new year.

On December 15, 1941, one week after the attack on Pearl Harbor, Kauffman was sent to Hawaii on a dangerous mission. An unexploded Japanese 551-pound demolition bomb, dropped just outside an ammunition bunker on Schofield Barracks, required his attention. Working with a gunner’s mate named Robert Eigell, Kauffman cautiously approached the projectile and began to dismantle it.

“You know how you always think of the Japanese as being very good with tricky things like booby traps,” he recalled. “It turned out that I couldn’t have set that bomb off if I’d had a sledgehammer… The fuze was completely faulty.”

Freshly decorated with a Navy Cross for his work in Hawaii, Kauffman returned to Washington just as his inaugural bomb disposal officers class began its 11-week program. As a final exam, his students underwent a practical exercise that lasted 29 hours straight—to see who got careless under conditions of extreme stress and fatigue.

While in Washington, Kauffman began dating his younger sister’s best friend—a vivacious college student named Margaret “Peggy” Cary Tuckerman. The two got engaged on Valentine’s Day, 1943, and were married May 1 in a lavish society wedding.

On the last day of their honeymoon, Kauffman was directed to meet Capt. Jeffrey C. Metzal of the Navy Staff in Washington. Metzal, who helped coordinate special operations, asked him if he had ever seen pictures of the obstacle belts that German forces were then building along the French coast. Kauffman had not and the captain described in graphic detail how soldiers would drown under the weight of their own equipment if submerged obstacles forced them to step off their landing craft too far from shore.

“I want you to put a stop to that,” Metzal said, telling Kauffman he was now responsible for setting up a school that instructed sailors how to find, mark, and destroy beach obstacles. “Pick a place to train your people,” Metzal continued, assuring him that he could have anyone he wanted on his staff. The job also came with a spot promotion to lieutenant commander.

The newly-established Naval Amphibious Training Base at Fort Pierce, Florida, was ideal. Located on a pair of barrier islands along Florida’s Atlantic coast, it enjoyed yearlong good weather and warm water—plus its isolated location helped assure secrecy. By mid-July 1943, Kauffman and his small cadre of instructors (most of whom came from the bomb disposal school) were installed in a tent city there.

A joint Army-Navy commando outfit called the Scouts and Raiders also trained on South Island and offered to help Kauffman welcome his first class of demolitions men—mostly ex-Seabees—to Fort Pierce. Their seven-day program of non-stop physical and emotional testing, conducted under the blazing Florida sun, instantly became known as “Hell Week”—a tradition that continues in the U.S. Navy’s SEAL selection school today.

Trainees endured long days of running on hot sandy beaches, swimming among poisonous jellyfish in rough surf, and wading through the alligator-infested Indian River while carrying rubber boats over their heads. At least 40 percent of the first class had quit or was in sick bay before Hell Week ended. “Many times I wanted to lay down and cry,” wrote one sailor, “but the sand fleas and mosquitoes wouldn’t let me.”

Kauffman also insisted that officers undergo the same training as their enlisted sailors. He directly participated in that first Hell Week, a measure that earned the respect of many students. Already, these so-called “demolitioneers” were building a spirit of esprit de corps that would help them get through many tough days in combat.

The trainees at Fort Pierce learned to work as part of a Naval Combat Demolition Unit (NCDU). Each team, consisting of one officer and six sailors, employed specialized explosive materials to reduce enemy beach obstacles. The NCDU men wore steel helmets, fatigue uniforms, life belts, and field shoes (boondockers), as they were not expected to do much swimming in the course of their duties.

One of Kauffman’s additional duties at Fort Pierce was as chairman of the Joint Army Navy Experimental Test (JANET) Board. The JANET Board’s mandate included coordinating service responsibilities for breaching enemy obstacles during an amphibious operation. The board also reviewed experimental equipment and techniques designed to counter shoreside fortifications like the Belgian Gate, a fence-like barrier that was recently observed on likely European invasion beaches.

Day and night, rows of wooden posts, steel tetrahedrons, and Belgian Gates were blown up by NCDU trainees all across uninhabited North Island. Once the students destroyed these obstacles, a crew of Seabees rebuilt them for the next class. An estimated 3,500 “demolitioneers” received training at Fort Pierce during World War II.

Despite the important work he was performing in Florida, Kauffman ached for service in a more active theater of operations. For him, a door of opportunity opened in the aftermath of a near-disaster at Tarawa. A combination of poor intelligence work, unexpected tides, and heavy Japanese opposition doomed hundreds of U.S. Marines as they stormed that atoll on November 20, 1943. Rear Admiral Richmond K. Turner, commanding the naval attack force that put them there, later wrote: “We must never make another amphibious operation without exact information as to the depths of water or without the ability to eliminate obstacles before the landing.”

Summoned to Hawaii, Kauffman left Peggy (who was six months pregnant with their first child) for a new and extraordinarily perilous assignment as commanding officer of Underwater Demolition Team (UDT) Five. The UDTs were a brainchild of Admiral Turner, who envisioned a large force of trained swimmers responsible for hydrographic reconnaissance in addition to eliminating beach obstacles. Each team would consist of 100 men (13 officers and 87 enlisted sailors) and go to war in a high-speed transport vessel—essentially, a modified World War I-era “four-stack” destroyer. Smaller landing craft carried on board would then transport the swimmers in toward shore and recover them once their mission was completed.

In April 1944, the new commander of UDT 5 met with Admiral Turner to receive his orders for Operation Forager, the invasion of Saipan. The briefing, as Kauffman related, began when Turner showed him a chart of Saipan’s west coast.

“I want you people to swim in to the beach about eight on D Minus One,” Turner said. “Make a detailed survey of the depths of the water, the obstacles, anti-boat mines, the gun positions ashore, surf conditions, and other details important to the landing forces. I also want you to blow out all obstacles in that 1,800 by 6,000-yard area.”

Kauffman, assuming the admiral meant 8 p.m., asked him how much moonlight was available. Turner, showing his temper, barked that he wanted the swimmers to go in at eight in the morning.

To this, Kauffman protested: “You don’t swim into somebody else’s beach in broad daylight, sir!”

“You do,” Turner curtly responded.

Kauffman then went on to meet the members of UDT-5, then stationed at the Naval Combat Demolition Training and Experimental Base on Maui. There was much to do before his team shoved off for Saipan. Every man practiced long-distance swimming using a new sidestroke technique. The despised steel helmets and boondocker boots came off, replaced by cotton trunks, canvas sneakers, knee pads, and a face mask.

The only weapon to be carried was a belt knife. Other tools of the trade included a grease pencil and Plexiglas slate for recording depth soundings. Additionally, swim teams (the UDTs always worked in pairs) employed marker buoys, balsa floats, and fishing line—55 miles of it—to survey their sectors and mark enemy obstacles or coral heads for demolition. To ensure their readings were accurate, Kauffman had his men’s bodies painted with black stripes every six inches.

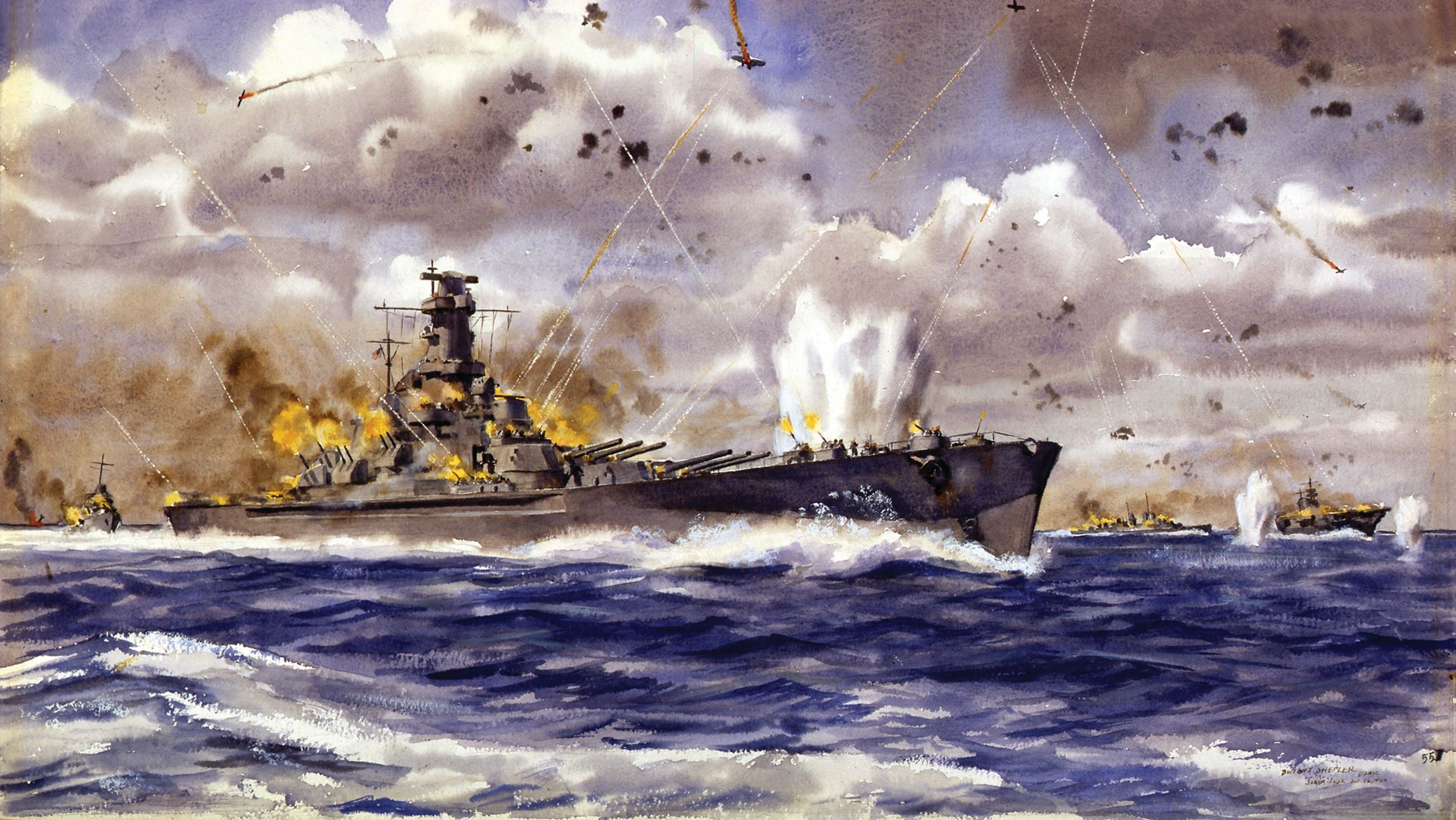

Midmorning on June 14, 1944, UDT-5’s “frogmen” slipped into the water off Red and Green Beaches, designated landing zones for the 2nd Marine Division’s amphibious assault the next day. With a barrage of naval gunfire shrieking over their heads, the swimmers got to work. Kauffman, eyeglasses taped to his temples, supervised operations from a motorized air mattress in the center sector.

As his swimmers neared shore, Kauffman could see splashes appear around their bobbing heads. Convinced that supporting warships (some of which were commanded by his father) were shooting short, he got on the radio to tell his Exec, Lieutenant John DeBold, they needed to lift their fire.

“Skipper,” DeBold replied, “those aren’t shorts.” Enemy shells, he explained, were making the splashes that worried Kauffman.

One UDT-5 frogman, Shipfitter First Class Robert Christensen, was killed when his “flying mattress” came under Japanese machine-gun fire. When two other swimmers were reported missing, Kauffman commandeered a landing craft and went in after them. Amid a shower of exploding mortar rounds, he somehow pulled both men to safety.

Of his sailors’ courage that day, Kauffman remarked: “Every single man was calmly and slowly continuing his search and marking his slate, with stuff dropping all around. They didn’t appear one tenth as scared as I was. I would not have been so amazed if ninety percent of the men had done so well, but to have a cold 100 percent go in through the rain of fire was almost unbelievable.”

Later that day, Kauffman briefed an assemblage of Navy and Marine Corps senior leaders on beach conditions at Saipan. He reported that both Red and Green Beaches could support an amphibious assault, but the Marines’ tank landing craft could not put in where the original plan specified. Suggesting an alternate route, he volunteered to lead the flotilla of tank-carrying vessels toward shore on D-Day using a borrowed “Alligator” tractor.

Kauffman’s frogmen again provided valuable service during the Tinian invasion in late July. Their thorough nocturnal reconnaissance of that island’s potential landing beaches convinced Admiral Turner to change his mind about putting the invasion force ashore opposite heavily-fortified Tinian town. Working with Marines of V Amphibious Corps’ Recon Battalion, sailors from UDT-5 and UDT-7 swam in to collect soil samples on two narrow strips of sand labeled White Beach 1 and White Beach 2.

Once more, Kauffman led from the front. He broke his last remaining pair of spectacles while covering himself in sand to hide from an enemy patrol but returned before dawn to pronounce the White beaches suitable for landing craft. The 4th Marine Division went in on July 24, and despite fierce enemy resistance managed to secure Tinian in eight days. Marine General Holland M. Smith, V Amphibious Corps Commander, declared it “the most perfect amphibious operation in the Pacific War.”

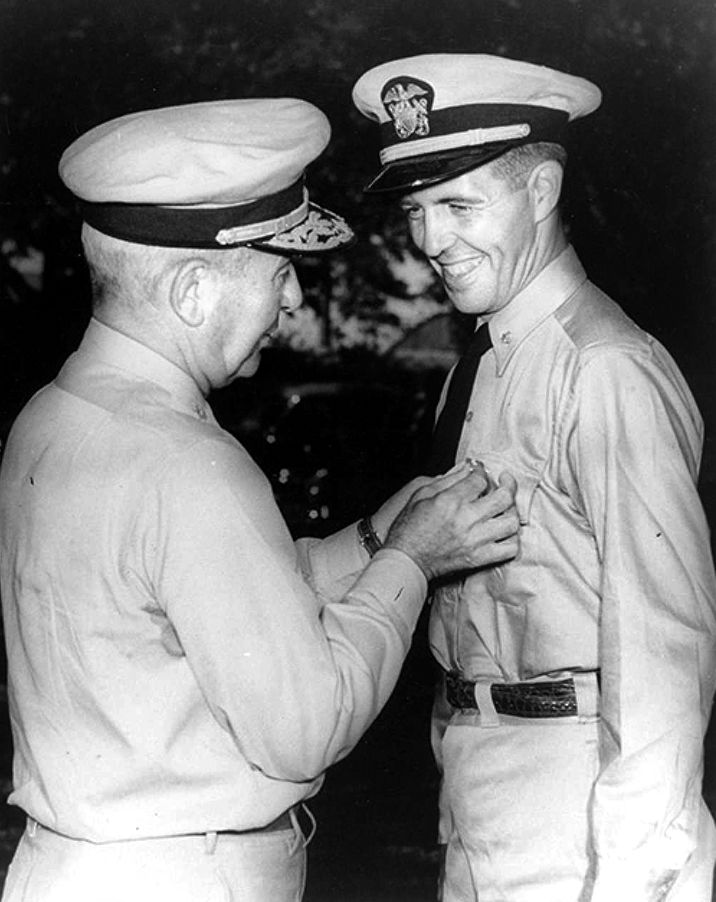

For Kauffman, Tinian marked his last combat swim. Reassigned in September as Chief of Experiments and Development on Maui, he was promoted to the rank of full Commander a few months later. For his valor in Operation Forager, Commander Kauffman was awarded a second Navy Cross—pinned on by his father.

Now assigned as commander of all Underwater Demolition Teams in the Central Pacific, Kauffman participated in the Iwo Jima and Okinawa invasions. At war’s end, wearing the four stripes of a Naval Reserve captain, he played a key role in preparing a number of landing beaches for Allied troops as they moved in to occupy Japan.

Despite his status as a decorated combat leader, Kauffman again faced difficulties when in 1947 he applied for a Regular Navy commission. Poor distance vision, an examining physician said, disqualified Kauffman from sea duty; putting his glasses back on, the resourceful frogman quickly memorized his eye chart and asked to retake the test. This time, he passed it easily.

Kauffman’s post-war career included command of the destroyer USS Gearing (DD-710), attack transport Bexar (APA-237), and heavy cruiser USS Helena (CA-75). Following promotion to rear admiral in 1960, he served as the United States Naval Academy’s 44th superintendent from 1965 to 1968. Retiring from the Navy in 1973, he died six years later. At his request, he was buried in the Naval Academy Cemetery.

Kauffman’s legacy lives on in the Draper L. Kauffman Leadership Excellence Award, presented yearly to an outstanding Midshipman Second Class at the U.S. Naval Academy. Another award bearing his name is annually bestowed on a deserving Navy Explosive Ordnance Disposal officer. The military has dedicated several training facilities in his honor, while the guided missile frigate USS Kauffman (FFG-59)—in commission from 1987 to 2015—recognized father-and-son admirals James and Draper Kauffman.

Known today as “America’s First Frogman,” Kauffman’s influence is perhaps best felt at the demanding Basic Underwater Demolition/SEAL Training School located in Coronado, California. There, aspiring Navy special operations warriors—officers and enlisted sailors alike—endure Hell Week, a rite of passage inaugurated 80 years ago by this bright, courageous, and inspiring combat leader who overcame great adversity in the service of his nation and fellow sailors.

Patrick J. Chaisson, a retired military officer and author, writes from his home in Scotia, New York.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments