By Bill Warnock

Shellfire rocked the aid station. A ceiling beam cracked, raining down plaster. One explosion obliterated a window, hurling stone, wood, and glass shards into the room. Father Francis L. Sampson rushed patients under a bed, fearing the building might collapse. He led everyone in the Lord’s Prayer while changing bandages and cleaning plaster dust from pallid faces. All the while he kept blood plasma flowing. The dozen wounded men watched the chaplain with awe. He was their lodestar, a beacon in death’s dark shadow. His internal gyroscope spun true and level, as if providence had created him for this task.

In the coming months, Father Sampson’s actions in Normandy would garner a Medal of Honor recommendation, a proposal supported by Supreme Allied Commander General Dwight Eisenhower. But the valiant priest would never receive America’s highest combat decoration.

This is the untold story behind the man and the medal.

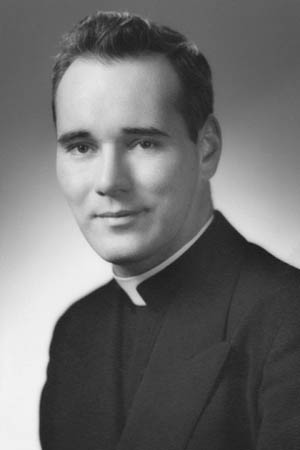

The intricate path to the aid station began in 1942 when Father Sampson answered a recruiting call for paratrooper chaplains. He later admitted his naiveté. “Frankly I didn’t know when I signed up for the airborne that chaplains would be expected to jump from an airplane in flight.” Fear of embarrassment kept him from reneging once he understood the term “airborne.”

The Army sent him to the parachute school at Fort Benning, Georgia, where his chaplaincy afforded him no lax treatment. At age 30, Francis Leon Sampson stood 5-10, weighed 185 pounds, and sported a flattop haircut. He excelled at athletics, but the school pummeled him into a deflated heap. Many trainees washed out or landed in a hospital bed, but he persevered even after a brush with death when he descended into the Chattahoochee River on one jump. He graduated in May 1943, unaware that his close call in the river foreshadowed events to come.

Imbued with new confidence, the chaplain boarded a train for Camp Mackall, North Carolina, the home of the 501st Parachute Infantry Regiment.

He reported to Colonel Howard R. Johnson, the regimental commander. The 40-year-old leader was an inexhaustible human dynamo who ignited sparks at every turn. He exhorted his men with fiery words, spurring them to surmount impossible odds and to shake the gates of Hell. The colonel also had a penchant for profanity, language the clergyman found offensive. He voiced dis

approval, and uneasiness developed between the two men.

The priest found instant rapport with his flock of Catholic paratroopers. His empathy, comedic talent, and love for all people endeared him to the men who dubbed him Father Sam.

The 501st fought mock battles for two months during the autumn in Tennessee. While there, Father Sam received his captain’s bars. He also qualified as a combat medic, having learned to apply a splint, infuse blood plasma, and perform other emergency procedures.

Overseas movement began on January 18, 1944, when the regiment embarked for England, where it joined the 101st Airborne Division. The regiment settled outside Newbury, and, as a security measure, adopted the codename “Klondike.”

Soon after arriving, the uneasiness between Johnson and Father Sam boiled into conflict when the colonel instructed his troops to carry condoms while on leave in London or anywhere else that venereal diseases and prostitutes proliferated. The rubbers filled a fishbowl, and the soldiers helped themselves. Father Sam expressed opposition, and Johnson fired back, “You take care of their souls Chaplain, and I’ll take care of their asses!” The priest bristled.

“The morals in England are worse than you can possibly imagine,” he explained in a letter home. “I am having a terrific struggle with our commanding officer to protect our Catholic boys’ rights of conscience. He is trying to enforce something contrary to our faith. My opposition may cost me my job.”

The padre appealed to the division chaplain, an Episcopalian colonel.

Several weeks later Father Sam again wrote about Johnson. “I have won the first couple rounds in our little feud, and he sure glares at me.”

The fishbowl disappeared, and the chaplain kept his job.

Cold, drizzling rain prevailed as preparations mounted for the Allied invasion of France. Practice jumps continued, and on one drop Father Sam landed in a lake, his second water landing.

On a night maneuver, the chaplain fell asleep in a ditch. He awoke feeling something cold pressing under his chin. “A snake!” he thought and slowly opened his eyes. It was a knife wielded by Johnson. “Chaplain,” he said, “in combat you’d have been a dead duck by now.”

Yet another travail unfolded when Father Sam fired his assistant, Private James W. McDermott, who repeatedly shirked his duties. The wayward clerk retaliated and stole £85 (about $340) from the chaplain’s desk. He fled the scene, threw a couple drunken parties, and betrothed himself to an English woman while his wife was pregnant back home. McDermott spent nearly all the money and eventually landed in the regimental stockade.

Several days after the larceny, the 101st conducted Exercise Eagle, a night drop on May 12, 1944, and a dry run for the division’s part in the invasion of Western Europe. On the way down, Father Sam struck a tree trunk and bruised his ribs. The regiment incurred 150 casualties that night with 90 percent of them requiring hospitalization. The losses ended all practice jumps and rigorous training.

The bruised priest initiated a new assistant, Private William A. France from Philadelphia. Born into an Episcopalian family, “Buck” France had recently converted to Catholicism. Father Sam had baptized him into the Roman Church a month earlier along with six other troopers.

The final countdown to peril began on May 28, when the regiment split its ranks between two airfields. Father Sam and his Protestant counterpart flew back and forth between them. Mass attendance soared, as did penance, the padre’s boys confessing their 10,000 venial sins.

Invasion architects assembled 821 aircraft, excluding spares, to haul 13,348 American paratroopers into battle. Just 13 jumpers were chaplains.

Father Sam quartered in a tent at Merryfield airdrome, home to the 441st Troop Carrier Group commanded by Lt. Col. Theodore G. Kershaw. Barbed wire and armed guards confined the paratroopers to the installation once they knew their destination—Normandy.

Rain and high seas delayed the operation 24 hours. On D-Day eve, Colonel Johnson addressed his Merryfield contingent. He brandished a Bowie knife above his head and swore to plunge it into the “foulest, black-hearted Nazi bastard in France.” He whipped the men into savage spirit before they saddled up with their gear and parachutes.

Father Sam’s accoutrements included a Red Cross brassard and two canteens, one filled with medical alcohol and the other with consecrated wine. He stowed religious items in a musette bag. The items included cards with the Latin texts for absolution and anointing the sick as well as a chalice and small ciborium, the latter safeguarding consecrated wafers. He wrapped the objects in altar linens and his white vestments. He also carried a gas mask, a dispatch case, a bulky medical bag, a blood plasma kit, and a second musette bag with toiletry items and extra underwear. K-ration boxes bulged his pockets.

He shook hands with men as they walked to the aircraft and bid “God bless you,” to each. Aboard his plane, the troopers bowed their heads, their faces blackened with burnt cork, and Father Sam led them in prayer.

Aircraft barreled down the runway, their Pratt & Whitney engines pulling them into the sky. The planes circled and climbed in the fading twilight and assembled over southern England. The lead ship reached the coastline at 12:31 am, the drop zone (DZ) less than an hour away.

Laden with gear, the chaplain lumbered to his plane’s open passenger door. He gazed down at the English Channel, its whitecaps illuminated by the moon. His eyes wandered across a breathtaking vista—naval vessels, too many to count, all steaming toward the invasion beaches.

In the cabin, engulfed by engine roar, Father Sam studied the deadpan faces. “The men were generally quiet,” he recalled. “Some tried to sleep, others smoked steadily, and a few tried to be nonchalant by humming some modern songs.”

He wondered how many would survive to see daylight again.

Ahead at the DZ, pathfinders were on the ground. These elite troopers encountered dogged enemy fire as they struggled to set up T-lights and Eureka radar to help guide the 441st. The Germans had identified the area as a potential landing zone, and they defended it.

Like everyone in the air, Father Sam knew nothing about the trouble on the ground, but a greater problem loomed ahead in the sky. An enormous cloud bank hung over the Normandy coast, an obstacle piled high with danger.

Still locked in formation, the pilots climbed to 1,500 feet, the altitude ordered for the coastline crossing. The aircraft reached land near Portbail, France, and plunged into the clouds, the DZ just 10 minutes away.

Visibility dropped to nil in places.

Anxiety gripped many pilots. They broke formation, hoping to avoid midair collisions. Aircraft veered left and right. Some dove, some climbed, and others held their course. Lt. Col. Kershaw bored straight ahead through the gray soup. Father Sam’s pilot stayed with the colonel, and they gradually nosed down to 700 feet, the jump altitude.

German antiaircraft fire shot into the clouds, albeit scattered and imprecise. The booms and flashes nevertheless set everyone on edge.

A red warning light suddenly glowed by the door, indicating to Father Sam and his fellow passengers that only four minutes remained to the DZ. He watched the jumpmaster, 1st Lt. Ted Fuller, pull himself to his feet and yell, “Get ready!” The men followed his commands and attached their static-line fasteners to an anchor cable that ran overhead in the cabin. They checked their equipment one final time.

German gunners spun a deadly web in the sky, zeroing in on the C-47 transport planes as they emerged from the clouds. Tracer rounds crawled high into the night, painting long, fiery lines that vanished as the rounds spent themselves and tumbled earthward.

Turbulent air rocked Father Sam’s aircraft, and bullets pierced its aluminum skin, shooting up through the floor. One projectile hit Technician Fifth Grade Stanley E. Butkovich and penetrated his left thigh. Waylen Lamb, a medic, clambered to the wounded man, who insisted on jumping. Lieutenant Fuller consented and unhooked Butkovich from the anchor cable and moved him to a seated position in the door, his legs dangling overboard. Fuller reattached Butkovich to the cable.

In the lead aircraft, Kershaw and his co-pilot scanned the ground for T-lights signaling the place where the paratroopers should receive the green light to jump. The aviators saw only flames leaping from a barn torched by the Germans to illuminate the invaders. Kershaw thought the DZ lay below, and he switched on the green light. Father Sam’s pilot copied.

Fuller gave Butkovich a shove out the door. Equipment bundles followed him, and then his comrades in rapid succession.

Father Sam stepped into prop blast and plummeted until his parachute deployed, its camouflaged canopy unfurling overhead. He marveled for a fleeting moment at the lethal fireworks all around. “It will always remain a mystery to me how any of us lived,” he later wrote. “I collapsed part of my chute to come down faster. From there on I placed myself in the hands of my guardian angel.”

It seemed his angel drew the short straw. Father Sam plunged into a flooded drainage ditch. His heavy gear pulled him beneath the cold, black water. Unable to find his feet, he fumbled for his knife and cut away his medical bag, plasma kit, toiletry bag, and religious items but failed to free himself from a watery grave. He would probably have drowned, but his canopy stayed open and a wind gust pulled him into shallow water.

He recovered for a moment and shed his parachute harness. German bullets zipped over the swamp as he crawled back to the ditch and dove for his religious items, especially anxious to save the ciborium and its sacred contents. After five or six attempts, he latched onto the musette bag and pulled it to the surface.

He spotted another man from his stick, his assistant Buck France, who had lost his rifle after nearly drowning. Soaked to the skin, the two scrambled to a hedgerow for cover.

They looked up to see a C-47 heading their way, flames gushing from its left wing. The dying bird approached low, its pilot fighting to regain control. The aircraft pitched into a field and exploded in an orange fireball that billowed high into the sky. The two onlookers prayed for the dead crewmen now cooking in the funeral pyre. The pair also prayed for the souls aboard two other flaming aircraft that blazed across the distant sky like giant bottle rockets.

Father Sam and his assistant soon found two more 501st soldiers who crawled to their position. The four weighed their options and moved out, hugging hedgerows while wending their way toward an area where they hoped to meet friendly faces.

They bumped into six airborne warriors who pointed out a circuitous route to a rally point. The route crossed a vast swamp. Back in 1942, the Germans had closed lock gates on the Douve River, and rainwater flooded the lowlands creating a barrier to airborne assault.

Father Sam’s group picked its way across the marsh until receiving enemy fire near a farm owned by Théophile Fortin. The chaplain advanced alone to a small house where he found an aid station and its officer in charge, Captain Tildon S. McGee, the Protestant chaplain for the 506th Parachute Infantry. Father Sam backtracked and led his group to the house.

McGee, a Baptist theologian from Philadelphia, Mississippi, had landed at Angoville-au-Plain, barely missing that town’s church steeple as he descended. The near calamity and its irony dawned on him, perhaps along with a narrowly avoided headline—“Chaplain Killed by Church.”

McGee had left Angoville and trekked across the swamp, helping evacuate casualties to the Fortin house where a dozen 506th medics gathered, as well as one from the 501st. Father Sam and his group were welcome additions.

Near the aid station, the 3rd Battalion, 506th dug in and defended two wooden bridges over the Douve River. Germans across the river chopped at the defenses with shells and bullets.

Father Sam witnessed a civilian tragedy when an enemy shell struck behind the house and killed the farmer’s wife, Odette Fortin, and an eight-year-old girl, Georgette Revet, after they stepped outdoors to fetch water from a pump.

“As I knelt to anoint them,” he recalled, “the farmer threw himself on their bodies and broke into agonizing sobs.” The priest placed a hand on the grieving man’s shoulder. He immediately sprang up, his face and hands smeared with blood, and ran toward the Germans, yelling and shaking his fists in rage.

Inside the aid station, several patients required care beyond that presently available. Father Sam decided to locate the 501st regimental aid station and a surgeon. He conferred with McGee and struck out alone across the marsh, avoiding roads and enemy eyes. The swamp flora concealed him as he skulked along through frigid water sometimes chest deep. He chanced upon a friendly patrol that directed him toward high ground and the Klondike aid station in a hamlet named Basse Addeville.

He plodded upslope toward his destination and toward a firefight, its tenor rising to a rapid crackle. The 501st men at Basse Addeville faced German Army troops one hedgerow away. The enemy included foreign legionnaires, ex-Red Army soldiers from Soviet Georgia.

The chaplain reached friendly forces and discovered GIs gathered around a recent casualty, a towheaded kid from Service Company—Technician Fifth Grade Norman L. Dick. His own hand grenade had detonated in a pocket. Somebody thought a bullet triggered the mishap, but, whatever the cause, the explosion turned his right leg into a bloody sluice. Father Sam helped carry Norman to the aid station.

Major Francis E. Carrel, the regimental surgeon, labored inside the medical facility, a one-story dwelling built during the 18th century. The house looked sturdy, its fortress-thick walls constructed from stone and torchis, a traditional building material made from clay and straw. An interior wall divided the building into separate residences. Noémie Diorey lived in the one now filled with American casualties. Her daughter Maria Lebreuilly owned the adjoining residence, where the two women took refuge.

Noémie’s first husband, Maria’s father, had perished during World War I. When the Germans invaded in 1940, Maria had two brothers-in-law who served as infantrymen. One died in combat, and the other lost both legs. The two ladies knew war and its pain, but never before had its horrors erupted at their doorstep.

Father Sam located Major Carrel as he tended to patients in the cramped, cavelike facility. The doctor listened to the chaplain’s report and sent Captain Clarence N. Sorenson, the 2nd Battalion surgeon, to the 506th aid station along with an enlisted man and supplies.

Father Sam returned outdoors and found Major Richard J. Allen, the regimental operations officer and the leader at Basse Addeville. Allen told Father Sam that Colonel Johnson held their unit’s initial objective, the Douve River locks at La Barquette. Most of the Basse Addeville defenders had departed for the locks. Allen now led a 50-man rear guard. These troops would leave at nightfall along with the chaplain, the medical staff, and the ambulatory patients. As for the men unable to walk, their fate lay in German hands.

Back at the aid station, Carrel and Father Sam discussed the immobile patients. “This is a bad time to leave them,” the doctor said. “Neither side is taking many prisoners now, and the Germans will consider them a liability.”

Father Sam regarded abandonment as an unthinkable sin even if dictated by the military situation, and he voiced his intent to stay. “I tried to discourage him,” Carrel recounted, “but he insisted. He felt his duty was with the men.”

The doctor felt freer to leave, but he doubted anyone at the aid station would survive, even though the padre downplayed the risk. The two men reviewed each patient’s condition, including Pfc. Thomas L. Hildebrand, who was sequestered next door in Maria’s cider room.

Hildebrand jumped with Company D, 501st and suffered a severe concussion on landing, which caused faulty memory, constant headache, and emotional outbursts like a neuropsychiatric casualty. “Better keep him away from the others,” Carrel said.

The doctor and chaplain also discussed young Norman Dick, and another patient overheard the physician’s prognosis. “He told the chaplain there was not much chance of this man recovering, but, if he did, he would lose his leg.”

Carrel summoned his sergeant and told him to select a medic to remain with Father Sam. The sergeant asked the medics to draw paper slips, one with the word “stay” written on it. Private Everett L. Fisher recalled the lottery. “I was the first to draw, and I picked the stay slip.”

The 22-year-old Fisher hailed from Little Valley, New York, where he left high school to work as a farmhand until drafted in September 1942. He joined the 326th Airborne Medical Company the next month. For the invasion, his unit assigned men to each parachute regiment, and Fisher jumped with the 501st. He met Father Sam for the first time at the aid station.

Noémie’s residence had two rooms connected by an interior door. Each room also had an exterior door exiting onto the street. The larger room functioned as a bedroom and a living area with a fireplace. The smaller room served as a pantry with a ladder that led up to a loft.

The final withdrawal from Basse Addeville began on schedule. Major Allen led his rearguard, the medical team, and the ambulatory patients across the swamp toward La Barquette as the sun disappeared and a full moon appeared.

Father Sam now had more space in the aid station and moved all but three casualties into the large room. There were 14 patients. He placed two men with injured legs next to a door to watch Hildebrand. The chaplain fashioned a white flag from a bed sheet and hung it outside.

He asked Fisher to scrounge for food. The medic brought back rations abandoned in the yard. He also collected bottles of wine and gathered eggs from the pantry. An elderly Frenchwoman, probably Noémie, brought milk and butter. The men possessed a squad stove with two burners, and they cooked eggs scrambled with crushed crackers, protein and carbohydrates for the patients.

The chaplain and medic cleaned wounds and sprinkled sulfa powder to prevent infection. They changed dressings and squeezed morphine into groaning patients. Father Sam administered blood plasma to keep Norman Dick alive as well as Corporal James F. Jacobson from Company C, 501st, who lay on Noémie’s bed.

The 20-year-old corporal, a Catholic kid from Chicago, had a bicep torn by shrapnel and a bullet hole in his thorax that produced internal bleeding. Blood loss caused his veins to collapse, requiring numerous attempts by the chaplain before he successfully infused plasma.

Norman Dick lay on the floor in a corner, clutching a wooden crucifix that Father Sam lifted from a wall. He received three plasma units and rallied enough to reminisce about his family as the chaplain sat by his side and listened.

Norman said he grew up in Saint Clairesville, Ohio, where his parents died during the Great Depression. He moved to Coalinga, California, after graduating from high school and lived with his sister and her husband. The former Ohioan loved woodworking and found employment as a cabinetmaker until volunteering for the parachute infantry in September 1942. Three brothers also served in uniform, one having earned a Purple Heart and a Silver Star as a B-24 Liberator bombardier on a mission over France.

By now most men in the building had fallen asleep. Father Sam urged Fisher to do the same, and he dozed off. The chaplain returned to the white flag and stood silhouetted in the doorway waving the sheet, hoping to prevent the enemy from attacking the aid station. He did that every 15 minutes. In the meantime, he tiptoed among the patients, watching over them. He helped Norman, a devout Presbyterian, say his prayers.

The day ended with Basse Addeville unprotected and the Germans unaware.

The village lay silent under the stars. Faraway artillery occasionally broke the hush, like rolling thunder, miles away. Father Sam continued alternating between the flag and the patients until he heard a disturbance.

“About 2 am Norman became delirious,” the chaplain recalled, “I rested his head on my arm and regularly wiped perspiration from his forehead. At intervals he would have a lucid moment and would squeeze my hand.”

In a low voice, the chaplain asked anyone awake to join him in prayer for their comrade. Jacobsen prayed despite his own injuries.

Norman Dick died about 3:30 am. Father Sam rolled his body in a parachute and laid him outside with Fisher’s help.

Roosters crowed as sunlight crept above the eastern treeline two hours later. Jacobson and the other wounded men remained alive, but the Germans had yet to arrive.

When Fisher awoke, he relieved Father Sam, a man almost sleepwalking. He napped for three hours, his first shut-eye since England. The medic prepared eggs and hot chocolate for the chaplain after his rest, and he had just enough time to wolf them down.

The casualties required care, and the two angels in olive-drab hustled to meet the unrelenting task. Fisher had a queasy feeling. “We’d heard many stories about what happened to American paratroopers when captured,” he recalled.

The Germans finally realized their opponents had abandoned Basse Addeville. Enemy paratroopers from the 6th Parachute Regiment approached the aid station at 10:30 am.

One enemy soldier darted past a wood-frame window that overlooked the street. Furtive glances through the opening revealed a machine-gun crew planting its weapon nearby. The tension reached a gut-twisting climax when the men heard pounding on the pantry door and shouts in German. Father Sam grabbed the white flag and told Fisher to remain inside.

The chaplain yelled, “All right” and opened the door. An enemy paratrooper thrust a machine pistol into the clergyman’s midriff and shouted, “Hände hoch!”

Father Sam raised his hands.

The Germans yanked the priest outside where he repeatedly pointed to a Christian cross on his collar and the Red Cross brassard on his left arm. None among the enemy paratroopers had ever seen an airborne chaplain. No such person existed in their regiment, and the Luftwaffe as whole had no chaplains, having disbanded them years earlier.

Two young Germans with dour, hostile faces prodded him down the road at gunpoint.

Three other German paratroopers kicked open the door to the large room and ordered Fisher outside with his hands raised. “I stepped into the doorway,” he recalled, “and a young German stuck a machine pistol in my stomach. It clicked, and the boys on the floor turned their backs, expecting me to get a belly full of lead.”

Fisher brought down his left arm enough to show his brassard to the enemy soldier, and he pulled away the machine pistol. Inside the aid station, the Germans tried to interrogate their captives and fired rounds into the ceiling to frighten them. The Germans ransacked both rooms, searching for weapons and food. They snatched all the remaining eggs.

Enemy soldiers also rousted Maria and Noémie. The women in their homespun dresses looked harmless, and the soldiers released them after rummaging through Maria’s home.

The two Germans with Father Sam marched him about a quarter mile before stopping.

“One of them pushed me against a hedgerow,” he recalled, “and the two stepped back about 10 feet and pulled the bolts on their weapons.”

The blood sank from his face when he saw the violence in their eyes. He tried to recite the Act of Contrition, but in nervous haste he said the Grace before Meals.

Shots rang out.

The chaplain saw a German noncommissioned officer running down the road. He had just fired into the air and was yelling at his comrades. The handsome noncom spoke to Father Sam in broken English. This German was a veteran campaigner, an “old hare,” and he shoved one of the would-be killers when he saw the priest’s credentials. The noncom snapped to attention, his heels clicking like a pistol shot. He saluted and bent at the waist, making a slight Prussian bow. The noncom produced a Sacred Heart medallion from under his uniform.

Father Sam breathed easy as his rescuer escorted him to an officer who summoned a fluent English speaker. The chaplain explained that he possessed no military information and asked to remain with his wounded men. The officer consented. Back at the aid station, Fisher heard the shots and presumed the worst. He and the others believed a massacre now awaited them, but they guessed wrong.

Their padre reappeared at the door with the noncom at his side. Father Sam looked relieved, almost cheerful. The noncom inspected the aid station top to bottom, including each man’s injuries. He promised to send a doctor. The wounded noticed the decorum shown toward Father Sam, a hopeful sign.

The noncom departed as his comrades dug in at Basse Addeville.

Work in the aid station resumed for the chaplain, but he carried on alone. He asked Fisher to stay with Hildebrand. Father Sam feared the mentally unbalanced soldier might heed an animal urge to bolt free, overpowering his two injured guards, and that the Germans outside would shoot him.

The injured men hobbled back to the aid station with help from Father Sam. He placed Sergeant Lowell E. Norwood and Corporal Elbert F. Yeager in the pantry since no floor space remained in the large room. Both men belonged to Company B, 501st. Norwood grew up in Paris, Tennessee, where he had a wife and two young boys. His older brother Ted was also a paratrooper. The Germans captured him in Italy the previous year and interned him at Stalag IIB.

Norwood, Yeager, and the other patients drew hope from Father Sam. As night settled over the countryside, their survival seemed possible, even probable.

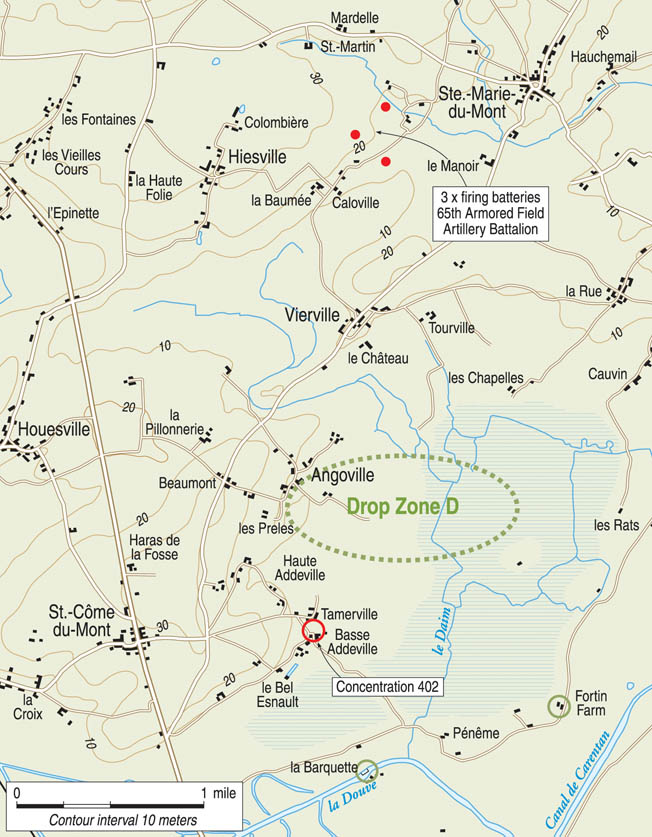

That night the 101st Airborne Division prepared to recapture Basse Addeville and to seize nearby Saint-Côme-du-Mont. The division had lost much of its own artillery during the D-Day drop and consequently received support from the 65th Armored Field Artillery Battalion.

The 65th, codenamed “Castle,” landed on Utah Beach. Its battalion fire direction center (or FDC) lay in a hamlet named Holdy. The unit fielded 18 M7 Priests, 105mm howitzers mounted on tank chassis. The guns sat in three firing batteries outside the hamlet.

Lieutenant Colonel Edward A. Bailey commanded the battalion. The 1938 West Point graduate visited the 101st command post at the Lecaudey farm in Hiesville, where he worked with the paratroopers to develop an artillery plan for the coming attack. They mapped out a rolling barrage that would sweep through orchards and pastures. They also selected eight targets, known as “concentrations,” that covered road junctions and enemy strongpoints. The staff at the Castle FDC plotted them on a firing chart and labeled each with a three-digit number. Concentration 402 included the Klondike aid station.

At midnight, the 65th began intermittent harassing fire intended to deny the Germans rest and to reduce their combat effectiveness. The artillerymen had no forward observer in place to adjust fire on the concentrations, but pinpoint accuracy was unnecessary. Battle maps and firing tables provided ample data for harassing fire.

The first detonation at Basse Addeville jolted everyone awake inside the aid station. More rounds screamed in and exploded, falling closer and closer to the building. The explosions produced supersonic shock waves and sound beyond decibel measure.

The wounded clenched their teeth and waited for a direct hit. Maria and Noémie huddled next door, both women terrified beyond words.

The artillerymen hammered away but soon lifted their fire and shifted it to another concentration. They returned to 402 several times that night.

The chaplain shuttled between the wounded and regularly ventured out to check on Fisher and Hildebrand. The concussion victim lay in a coma-like sleep, cocooned from reality.

One patient in the large room, Private John C. Marnye from Company D, 501st, recalled the chaplain’s poise. “Father Sampson was just as calm as if nothing was happening.” Marnye saw a man who had reached deep inside to some guarded corner and found grace, a man grateful to be where most needed, optimistic in the direst of circumstances.

Less than three miles away, muzzle flashes from the three howitzer batteries attracted at least one German aircraft. Two bombs landed near the guns but failed to explode. The artillerymen ignored the aircraft and continued blasting away. At 4:15 am, they stepped up their fire to a steady drumbeat.

Shells struck Basse Addeville with unprecedented fury. The aid station had avoided a direct hit, but that changed when an explosion split the darkness with blinding light and a booming crash. The seismic blast hurled the aid station occupants into an unworldly miasma, a place between life and death where time stood still.

Three hits in quick succession brought down the pantry roof and walls. Father Sam thought the large room would also crumble, and he threw himself over three men. Miraculously no collapse followed. The detonations left the chaplain’s ears ringing, but he somehow heard a voice call his name. It was Corporal Yeager.

The 23-year-old paratrooper from Iola, Texas, lay in the pantry doorway. Father Sam stumbled to him through a dusty haze as more wreckage fell and buried Yeager to the waist. The chaplain cradled the corporal’s head in his lap. “Father, they got me,” he said. The padre turned and said, “Let’s all pray for this boy.” Yeager moaned a couple of times, and Father Sam felt the young man’s heart pump hard for a minute before it stopped.

There was another man in the pantry. The chaplain climbed into the room and dug through the debris until he found Sergeant Norwood dead.

Amid the cataclysm, Father Sam noticed that a shell burst had propelled a GI flashlight onto the street. The light’s tiny bulb shone bright, and he feared that an artillery observer might see it. He leaped outside to switch off the light as shells continued to explode nearby.

The bombardment flummoxed the German defenders, and Father Sam heard their wild shouts. He almost collided with one who darted past. As he bent to grab the light, he saw a wounded enemy soldier in a watery ditch. The man died as the chaplain attempted to lift him.

Father Sam headed back indoors but recoiled upon seeing a German slumped against the building with an assault rifle. The weapon posed no threat, its owner a walleyed cadaver.

The chaplain hustled into the large room just as a shell exploded near the doorway and brought down more of the building. The blast injured a German outside who screamed for help. Father Sam wanted to assist, but his patients beseeched him to stay put.

The artillerymen halted their fire at 4:40 am, but only for five minutes.

When they resumed, their guns delivered a massive barrage in a box-shaped area facing the 1st Battalion, 401st Glider Infantry Regiment. High-explosive shells tore raw holes in the ground and shot up fountains of earth. White phosphorus projectiles radiated fire and noxious smoke. The aid station lay outside the impact zone, but the building trembled. After 10 minutes, the shelling turned to a rolling barrage that advanced 100 yards every four minutes.

Glider troops edged forward behind the barrage as daylight returned to Normandy. The attacking force also included two jeeps and trailers loaded with men and supplies from the 501st, the men tasked with reaching Johnson at La Barquette.

First Lieutenant Sumpter Blackmon led the jeep-borne force. He and his soldiers received enemy fire, and they responded with rifles, grenades, and two vehicle-mounted machine guns. The exchange killed a jeep driver, Private First Class John A. Houlihan. The men knew nothing about Father Sam’s aid station, and they thumped the building with rifle grenades.

Bullets also smacked the aid station, and a bright red tracer flew through a shattered window and ricocheted down from the ceiling. It passed through Father’s Sam pants, setting them on fire, as well as a wool rug. He quickly smothered the flames but sustained second-degree burns on his groin. The skin bubbled and blistered, yet he brushed off the pain and kept working after dressing the wound.

As German resistance wilted, Blackmon’s men hastily searched each house except the aid station because they received no fire from that building. The lieutenant’s party soon motored on to La Barquette and delivered the supplies.

The rolling barrage ended at 6 am, but small-arms fire rattled on.

At La Barquette, Colonel Johnson instructed Blackmon to begin evacuating casualties. The jeep teams loaded wounded men aboard the trailers and began making trips to a surgical facility established by the 101st at the Château de Colombière in Hiesville.

The journey was 10 miles roundtrip, and on the last ferry mission Blackmon learned about the wounded left with Father Sam at Basse Addeville.

The jeeps sped back there, and Blackmon headed for the one house ignored earlier. Only its north and south ends stood. As he approached, the lieutenant clutched a hand grenade, unsure what to expect. Masonry and broken rafters blocked the front door, so he circled to the rear.

Fisher saw Blackmon and shouted, “Americans in here!” Father Sam dashed outside, yelling to prevent another tragedy. The two officers met, and Blackmon learned that 11 wounded paratroopers had survived. He also noticed the chaplain’s injury. “His trousers were in tatters, and there was something wrong with his leg,” Blackmon recalled. “I asked him if he was hurt. He said no, that I was to get these men out and take care of them.”

The lieutenant explained that wounded soldiers already filled his two trailers, but he and the jeeps would return. He surveyed the devastated aid station before leaving Father Sam, who now had the squad stove back in operation.

Sniper fire erupted when the jeeps returned. One shot hit Blackmon’s driver, Pfc. Roy L. Spivey, who suffered a lacerated scalp that drenched his face in blood. His buddies sprayed bullets into foliage along the road and flushed out two shooters, young parachute soldiers in camouflaged smocks who promptly surrendered. The incident occurred near the aid station. Father Sam witnessed the aftermath. Both prisoners bubbled with contempt, their minds molded by a National Socialist education that twisted them into hate machines wholly committed to Adolf Hitler. They snickered at Spivey and hocked saliva on the ground.

Their insolence enraged Blackmon’s men. His radio operator, Private John T. Leitch, leveled a carbine at the Germans. Father Sam realized Leitch’s intent and ordered him to stop, but Leitch riddled the pair. The murder of unarmed men, even Nazi ideologues, sickened the chaplain. He felt obliged to initiate judicial action against Leitch, but that could wait.

The time had come for the aid station survivors to make their exodus. Father Sam and Fisher helped carry men to the trailers, the most seriously injured first.

Private Floyd H. Martin from Company C, 501st had wounds to his face and shoulder caused by machine-pistol bullets. He was only 16, having lied about his birth date when he enlisted. The underage paratrooper marveled at the aid station and its bashed-in roof. “Looking at the house the next day when we left it, I can’t figure out how we ever came out alive.”

Maria and Noémie also survived the building’s destruction.

The evacuation required three back-and-forth excursions to Hiesville. Father Sam stayed at the aid station until the final pickup.

As he waited, 2nd Lt. Elder B. Collier from Company D, 501st led a patrol into Basse Addeville to hunt for German holdouts. His men dislodged an enemy officer and his orderly from one house. Collier later recalled seeing the chaplain. “He was filthy and tired-looking, and he was very noticeably quiet.”

Father Sam departed in the last jeep.

At the Château de Colombière, a stone edifice that looked like a medieval fortress, he found Captain Joseph A. Duehren, Catholic chaplain for the 401st Glider Infantry. Duehren recalled, “We helped where we could, carrying the wounded men in, taking them to the operating room, administering the Last Sacraments and administering to their material wants.”

About an hour after Father Sam arrived, he answered an urgent call for Type O blood, the universal blood group. He rolled up his sleeve and gave two pints for a soldier with an abdominal wound and a rare blood type.

“At 0230 he sent me to bed,” Duehren recalled. The 501st chaplain carried on alone among the wounded, catnapping when he could. He worked at the chateau until about noon on June 9, when a lieutenant from his regiment arrived with wounded men and drove him to Vierville where Colonel Johnson assembled the regiment.

Two paratroopers dug Father Sam a foxhole and stuffed it with a parachute for bedding. As he flopped into the downy nest, a German aircraft dropped three bombs nearby, but, as he later explained, he was too exhausted to care. “If the whole German Luftwaffe came over, it couldn’t have kept me from going to sleep. I slept 24 hours straight through.”

Combat ended for the 501st in mid-June, and its survivors returned to England by ship in July. The regiment received new men to replace those lost.

First Lieutenant Richard Engels joined regimental headquarters and became personnel officer, replacing a captain who died of wounds. First Lieutenant Laurence S. Critchell Jr. became his assistant. Among their duties, the two newcomers oversaw awards and decorations.

The duo sent Bronze Star and Silver Star recommendations to division headquarters for Maj. Gen. Maxwell D. Taylor’s approval. He possessed sole decision-making authority for these decorations. Colonel Johnson also had 10 men whom he nominated for the Distinguished Service Cross (DSC), the nation’s second highest decoration for combat valor. Final decisions on these rested with higher headquarters in Europe.

Johnson also asked Engels and Critchell to prepare a proposal for the Medal of Honor. News about Father Sam’s deeds reverberated through the regiment and changed the colonel’s attitude toward his Catholic chaplain. The padre exemplified selflessness and regarded his own survival as incidental, traits that Johnson valued above all else. After Normandy, no man in the regiment inspired more respect from Johnson.

Army Regulation 600-45 stipulated that a Medal of Honor recommendation contain “incontestable proof” in written form, namely eyewitness affidavits. Engels took sworn statements from aid station survivors now in England. Critchell traveled to the 81st General Hospital in Cardiff, Wales, to interview Jacobson and obtain his statement. The two lieutenants collected a dozen affidavits. The regimental draftsman, Private Val B. Suarez, created a map, and Critchell wrote a three-page narrative detailing the full story.

Johnson submitted the recommendation to General Taylor on August 7. He promptly endorsed it, but for a lower decoration, the DSC.

Taylor himself lacked the authority to approve or disapprove a Medal of Honor. The War Department reserved that prerogative for itself. The division commander could offer only an opinion. The War Department also required that the division commander send the recommendation up the chain of command without regard to his own opinion. Taylor complied.

Father Sam informed his family, “I have been put in for the Congressional Medal of Honor,” he wrote. “I know you will be as thrilled by the honor of my being recommended as I was surprised.”

The recommendation reached First Army headquarters on August 18. Seven days later its Awards and Decorations Board reviewed the documentation, and the three colonels on the board agreed with Taylor and voted for the DSC.

On September 1, Father Sam mailed another letter home. “The little matter I wrote about in my last letter did not go through. It was changed to the Distinguished Service Cross, and I am afraid that is quite above and beyond anything I may have done in combat.”

The chaplain misunderstood the process. No final decision had occurred.

Major General William B. Kean, chief of staff for First Army, studied the recommendation and scribbled a terse note: “Ask the board to reconsider for MH. Maybe I am wrong but believe it is strong enough.”

The board reconvened on September 2, and two colonels changed their votes to Medal of Honor. First Army commander, Lt. Gen. Courtney H. Hodges, then endorsed the recommendation, giving a nod for the Medal of Honor. His staff sent the paperwork on to Lt. Gen. Omar N. Bradley at Twelfth Army Group headquarters.

While the papers traveled from desk to desk, the 101st and Father Sam returned to combat. The padre made his fourth water landing when he descended into a Dutch castle moat.

Colonel Johnson died on October 8 from an abdominal wound caused by a shell fragment. The steely-eyed chieftain passed into legend. He had forged his paratroopers into a lethal instrument of destruction, but the only man he deemed Medal of Honor worthy was a priest, a man with no weapon, no bravado, and no killer instinct.

The week after Johnson perished, General Bradley’s board recommended approval for the Medal of Honor. Bradley concurred, adding his signature. In November General Dwight D. Eisenhower lent his support and forwarded the recommendation across the Atlantic.

The documentation arrived at the Pentagon just after Thanksgiving. The War Department Decorations Board scrutinized the affidavits and Critchell’s narrative. On November 28, Board President, Maj. Gen. Emory S. Adams, announced its vote—Medal of Honor.

The file folder with the paperwork landed on Army Chief of Staff General George C. Marshall’s desk for final approval. The top Army officer delegated much responsibility to subordinates, untangling himself from a jungle of decisions and paperwork. He focused on issues impacting the war’s outcome but made an exception regarding the medal. He reviewed each proposal for its award, affirming or rejecting the recommendation made by his Decorations Board. Only the president or secretary of war could overrule his decision, and they seldom intervened.

Although an Army regulation governed the process, unwritten policies played a role. One policy held that “non-combatants,” namely chaplains and medical personnel, deserved no place among Medal of Honor recipients. General Marshall loosened the policy as the war progressed and permitted five combat medics to receive the medal, but he never wavered on chaplains.

He lowered Father Sam’s decoration to the Distinguished Service Cross.

A staff officer recorded the decision on December 2, 1944, without explanation.

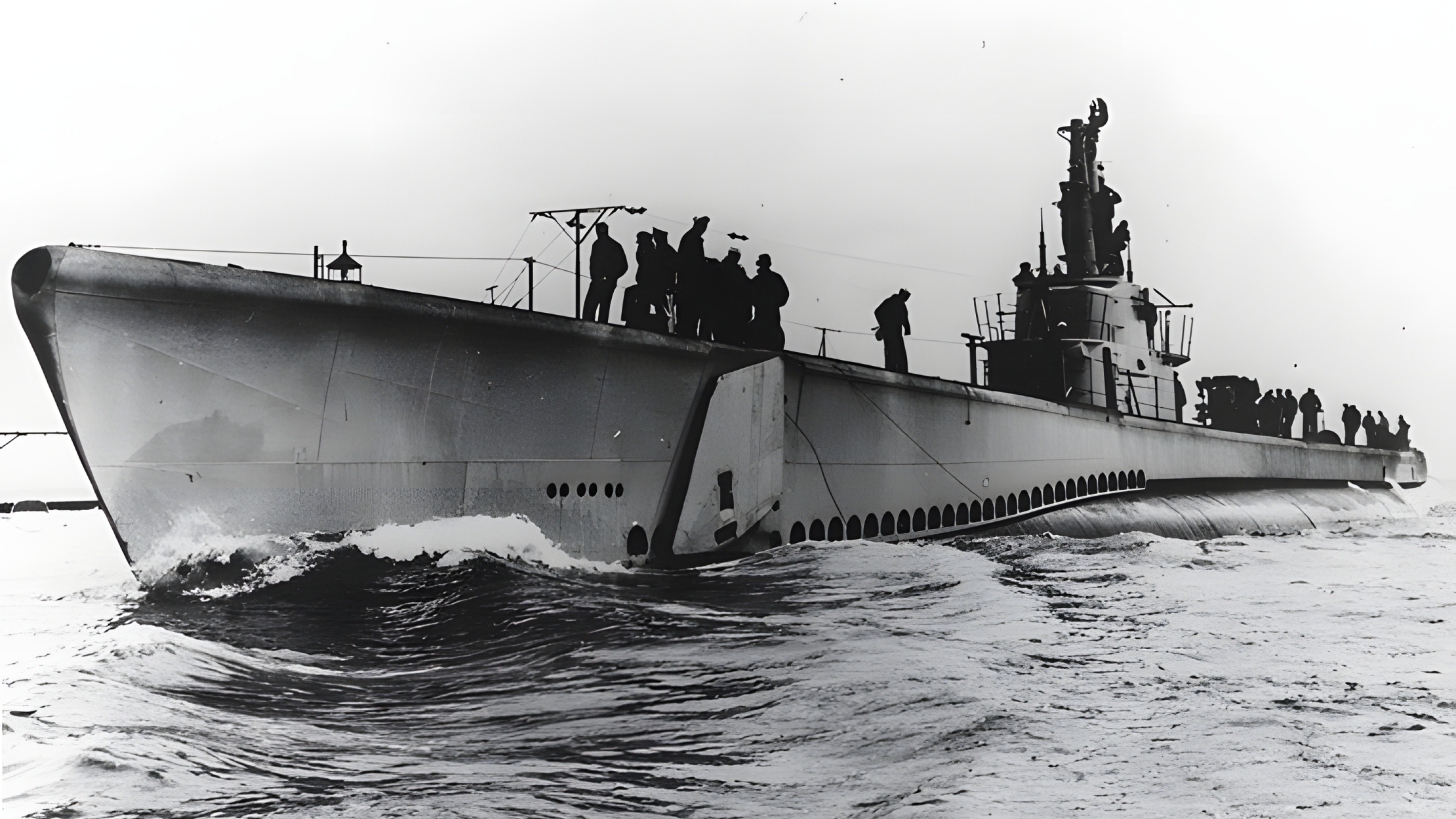

The same month, four other chaplains had their Medal of Honor recommendations lowered to the DSC. The four men, one Jewish, one Catholic, and two Protestants, had died together in 1943 after giving their life jackets to fellow passengers when their ship sank following a German submarine attack. The drowned clergymen and Father Sam were the only U.S. Army chaplains nominated for the Medal of Honor during World War II.

Back in Europe, Father Sam fell into German hands on December 20 while searching for casualties during the Battle of the Bulge. The Army reported him missing in action. In February 1945, his family received a letter from him through the International Red Cross. He was a prisoner at Stalag IIA. The Army contacted his father in Portland, Oregon, and arranged for a DSC presentation ceremony. His father received the decoration on his son’s behalf.

Soviet troops seized Stalag IIA in late April. Father Sam journeyed home and separated from the military but returned to active duty in 1946 due to a chaplain shortage.

He made his final combat jump—and fifth water landing—with the 11th Airborne Division during the Korean War. The conflict lasted three years, and no army chaplain received the Medal of Honor, the bar still set beyond their reach.

Father Sam made the military his career and ascended to major general in 1967 and became Chief of Chaplains, the highest post for a U.S. Army chaplain. The general occupied a Pentagon office and exerted influence at the top.

It was no coincidence that in 1968 an Army chaplain received the Medal of Honor for rescuing 20 wounded soldiers in Vietnam. The following year, another Army chaplain received the medal, a posthumous award to a paratrooper padre killed in Vietnam.

Father Sam retired from the army in 1971 and guided the USO for two years as its national president. Afterward, he relocated to South Dakota and became a parish priest in the Sioux Falls Diocese. He remained there until 1983, when he accepted a position at the University of Notre Dame as special assistant to the president for ROTC affairs.

Few people knew about his Medal of Honor recommendation. He omitted it from his published memoir along with all mention of awards and decorations, but in 1986 he shared the story with Sgt. Maj. Francis X. Boyle Jr., chief ROTC instructor at Notre Dame. The story amazed the sergeant major, who wrote to Senator Dan Quayle and called for a “congressional inquiry” to rectify what Boyle considered an injustice.

The senator investigated and received a courteous response from the Military Awards Branch at the U.S. Army Military Personnel Center. The responding officer explained that in 1952 Congress had terminated Medal of Honor awards for World War II deeds, and the Army had no power to waive that statutory restriction. The respondent also explained that General Marshall personally made the decision in Father Sam’s case, and it would be “presumptuous” of the Army to arbitrarily review the general’s “subjective judgment” after so many years.

Boyle reluctantly dropped the matter. He died two years later at age 50.

The chaplain returned to Sioux Falls in 1987, having retired again, though he occasionally substituted when a local priest was ill or away from town.

Father Sam led a humble but happy retirement, residing in a tiny wood-frame house once owned by his maternal grandparents. He underwrote school tuition for local families who lacked his pension and investments, and he donated funds to build a school chapel. The former general spent little on himself, his frugal habits tied to his spiritual convictions. Cigars were his one indulgence. He smoked pipes as a young man, later switched to cigarettes, and finally settled on cigars, fat stogies as well as slender cigarillos.

Cancer ended his twilight years. He died in hospice care on January 28, 1996.

Several months later, Congress made an exception to its statutory restriction and permitted the U.S. Army to award Medals of Honor to soldiers denied the decoration on racial grounds during World War II, reversing an unwritten policy that created a bias against them. Seventeen years later, the Army upgraded a DSC posthumously awarded to a Catholic chaplain during the Korean War, but that Medal of Honor involved no prior denial.

The rationale behind General Marshall’s disapproval remains unclear.

Marshall belonged to the Episcopal Church, but his wartime writings reflect esteem for Catholic chaplains, more so than many of their Protestant peers. Denominational prejudice played no discernable role in his judgment regarding Father Sam.

The general and the chaplain possessed similar moral qualities. Altruistic to the core, both men bridled their egos, scorned vanity, and declined advantage. Self-denial fit them like comfortable shoes. Did the general believe the Medal of Honor contradicted the solemn vows of men whose vocation ran contrary to fame and personal reward?

Whatever motivated the 1944 decision, it spared Father Sam all the fanfare and hero worship that often accompany the medal. He preferred that laurels fell upon others and that only the Almighty merited worship.

It was never the medal that mattered, only the lives saved.

Bill Warnock authored The Dead of Winter, a 2005 book chronicling present-day efforts to recover missing U.S. soldiers killed during the Battle of the Bulge. He received a 2010 Distinguished Writing Award from the Army Historical Foundation. Bill is currently writing a history of the U.S. 741st Tank Battalion in World War II. While conducting research for that book, he chanced upon the Medal of Honor paperwork drawn up by Engels and Critchell. The yellowed and forgotten pages propelled a quest to uncover the story presented here.

Dont know if you will get this, but you mention my great uncle John Leitch…apparently he gunned down two nazi POWs unfortunately. He played as an extra in the movie Battleground. He came up missing in the early 1960s and our family has not seen him since. I have his service serial number. Dont know if anyone can help, but we have been looking for him for a very long time. His sister Bev is still alive, but not for long. Any help would be appreciated.

Hi Steve,

After a search online I came across this post. Recently I discovered a US Army ID tag in Holland who wares your uncle his name. Is his army serial number 15324587?

We can get in touch directly if you want.

Regards Raymon

The 187 Regt. Combat. Team jumped in Korea, not 11th Airborne. Sampson was with them. I knew Fr. Sampson in 1955 while serving with 11th Abn at Ft Campbell.

good times

FATHER SAMSON WAS AN AMAZING MAN. A hero to many . Fr. SAMSON SAVED MY GREAT UNCLES Life. Another Extraordinary man . His name was James Francis Jacobson . My name sake. Although few men could could be as Courageous ,or Phenomenal !

My father, PFC William “Buck” France (1923-2009) confirmed much of the above from short anecdotes told to me over his lifetime.

Father Sam also was the person who received the order to relieve private Nyland of his required service. (The real life name of Private Ryan). When private Nyland was told that he could return home because his brothers had been killed in action, he said he was staying because he was with his brothers.

Thank you for sending this article along.

William Buck France was my hero long before I knew any of this.

May God continue to bless all who serve in the name of Freedom ??❤️??