By Blaine Taylor

Late in the evening of June 25, 1950 U.S. Secretary of State Dean Acheson was at his Maryland farmhouse reading when a call arrived to inform him of a serious situation in the Far East. He telephoned President Harry S Truman at the latter’s Independence, Mo. home that same Saturday evening and told HST, “Mr. President … the North Koreans are attacking across the 38th Parallel.”

The next day, President Truman returned to Washington aboard his aircraft Independence for an emergency meeting of the top-level Security Council at Blair House, his temporary residence while the White House was undergoing renovation.

The President heard and approved a triad of recommendations, namely, first, to evacuate all American civilian dependents from the South Korean capital of Seoul; second, to air-drop supplies to the embattled Republic of Korea (ROK) forces under attack; and third, to move the U.S. fleet based at Cavite in the Philippines to Korea. Another caveat was that there would be no Nationalist Chinese forces sent from Formosa to fight in South Korea.

Meanwhile, far away from the nation’s capital in Allied-occupied Japan, America’s Supreme Commander there—five-star General of the Army Douglas MacArthur—picked up the telephone by his bedside in the American Embassy in Tokyo. He, too, was told that the North Koreans had struck in great strength.

Long familiar with all the countries of Asia, MacArthur thus described Korea in his 1964 memoirs, Reminiscences: “Geographically, South Korea is a ruggedly mountainous peninsula that juts out toward Japan from the Manchurian mainland between the Yellow Sea and the Sea of Japan. An uneven north-south corridor cuts through the rough heart of the country below the 38th Parallel, and there are highways and rail links on both the eastern and western coastal plains.” He knew that the existing ROK forces were very weak: four divisions along the Parallel and, although well trained, “organized as a constabulary force, not troops of the line. They had only light weapons, no air or naval forces, and were lacking in tanks, artillery, and many other essentials. The decision to equip and organize them in this way had been made by the [U.S.] State Department.” As for their North Korean People’s Army opponents, they, MacArthur knew, had “a powerful striking army, fully equipped with heavy weapons, including the latest model of Soviet tanks,” the vaunted T-34 that had shattered the German Wehrmacht.

The mathematical equation of the rival forces on the ground was both simple and deadly: 100,000 ROKs versus 200,000 NKPAs—plus no modern weapons for the defenders as opposed to all modern weapons for the attackers. The method of the North Korean steamroller-like advance was also quite basic: Swing left and then right of their opponents’ lines in broad, flanking movements, so well practiced by British line infantry regiments during the entirety of the Napoleonic Wars of the previous century, and then plunge through any opened gap in the enemy center.

Disdaining President Truman’s term for Korea as a “police action,” his man in Tokyo privately thought, “Now was the time to recognize what the history of the world has taught from the beginning of time: that timidity breeds conflict, and courage often prevents.” Right from the start, therefore, the general misread the mettle of his commander-in-chief, just as the latter did him.

Nevertheless, in these early hours and days of dire emergency, the man in Washington turned to the man in Tokyo: “I was directed to use the Navy and the Air Force to assist South Korean defenses … also to isolate the Nationalist-held island of Formosa from the Chinese mainland. The U.S. 7th Fleet was turned over to my operational control.”

The British Asiatic Fleet was also placed under his command and, with his historic corncob pipe clenched between his teeth, MacArthur flew out of Haneda Airport aboard his old wartime plane the Bataan to take a first-hand, on-the-ground look at the fighting in Korea.

Upon arrival, he came almost immediately under enemy fire. He commandeered a jeep. “Seoul was already in enemy hands,” he later wrote. “It was a tragic scene. I watched for an hour the disaster I had inherited. In that brief interval on that blood-soaked hill, I formulated my plans. They were desperate plans, indeed, but I could see no other way except to accept a defeat which would include not only Korea, but all of Continental Asia.”

How could that have been, this instant of genius in the midst of overwhelming catastrophe and seemingly hopeless rout? Asserted his later compatriot and eventual successor, Lt. Gen. Matthew B. Ridgway in 1986, “He was truly one of the great captains of warfare.” Like Napoleon who would nap on a battlefield by his horse as deadly cannonballs would claim the lives of lesser mortals, Douglas MacArthur was lofty and serene in his genius, utterly convinced in his purpose, and absolutely determined that he would see all his plans through to completion or die in the process.

Formulating a Battle Plan

Clear-eyed and alert despite his 71 years, with thinning hair but no gray, MacArthur set about his plans. On July 23 he cabled to the Joint Chiefs of Staff at the Pentagon the basic tenets of his plan, to be called Operation Chromite. “Operation planned mid-September is amphibious landing of two division corps in rear of enemy lines [150 miles behind NKPA lines, far to the north of the Pusan Perimeter fighting where General Walton Walker’s 8th Army was fighting for its life and what little Korean territory remained to it] for purpose of enveloping and destroying enemy forces in conjunction with attack from south by 8th Army.…”

Ironically, unlike other U.S. Army generals of the day (like Omar Bradley, who stated openly that seaborne landings were obsolete), MacArthur was a distinct rarity—an army leader who firmly believed in amphibious operations, based on his own previous wartime experiences in the Pacific against the Japanese Army, working hand-in-glove with the U.S. Navy. Moreover, unlike Truman, Bradley, and former U.S. Defense Secretary Louis Johnson (who was fired the day before Inchon was launched, and replaced by General Marshall), MacArthur was not against the Marine Corps. Indeed, having first planned to use the army’s lst Cavalry Division as his projected lead assault unit of what was to be called the X Corps, he changed his mind and asked for—and got—the 1st Marine Division instead.

Secretary Johnson had even gone so far as to assert that “the Navy is on its way out.… There’s no reason for having a Navy and a Marine Corps,” feeling instead that the new U.S. Air Force could take over both services’ functions. At Inchon, MacArthur used navy ships, Marine aerial Corsairs and Marine and army troops jointly, in a superb example of inter-service cooperation.

In late August, in the Dai Ichi Building in Tokyo, America’s “proconsul for Japan” listened politely to all the arguments against Operation Chromite, and the dire prophecies of doom that it would fail ignominiously. The obstacles were formidable, indeed. MacArthur later wrote: “A naval briefing staff argued that two elements—tide and terrain—made a landing at Inchon extremely hazardous. They referred to Navy hydrographic studies which listed the average rise and fall of tides at Inchon at 20.7 feet—one of ‘the greatest in the world.’ On the tentative target date for the invasion, the rise and fall would be more than 30 feet because of the position of the moon.

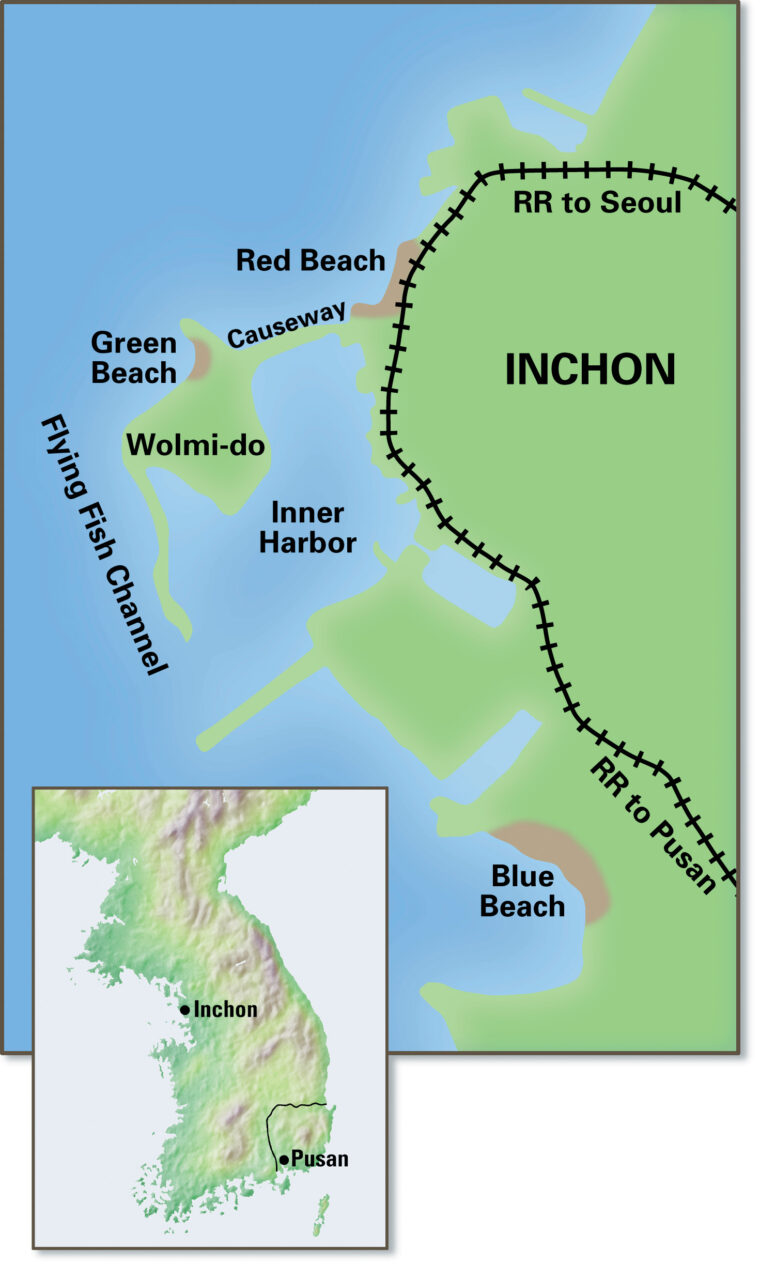

“When Inchon’s tides were at full ebb, the mud banks that had accumulated over the centuries from the Yellow Sea jutted from the shore in some places as far as two miles out into the harbor, and during ebb and flow these tides raced through ‘Flying Fish Channel,’ the best approach to the port, at speeds up to six knots. Even under the most favorable conditions, ‘Flying Fish Channel’ was narrow and winding. Not only did it make a perfect location for enemy mines, but also any ship sunk at a particularly vulnerable point could block the channel to all other ships.

“On the target date, the Navy experts went on, the first high tide would occur at 6:59 am, and the afternoon high tide would be at 7:19 pm, a full 35 minutes after sunset. Within two hours after high tide most of the assault craft would be wallowing in the ooze of Inchon’s mud banks, sitting ducks for Communist shore batteries until the next tide came in to float them again.

“In effect, the amphibious forces would have only about two hours in the morning for the complex job of reducing or effectively neutralizing Wolmi-Do, the 350-foot-high, heavily-fortified island which commands the harbor and which is connected with the mainland by a long causeway. …

“Assuming that this could be done, the afternoon’s high tide and approaching darkness would allow only 2 1/2 hours for the troops to land, secure a beachhead for the night, and bring up all the supplies essential to enable [the] forces to withstand counterattacks until morning. The landing craft, after putting the first assault waves ashore, would be helpless on the mud banks until the morning tide.”

And then there came the icing on the cake. “Beyond all this,” MacArthur recalled, “the Navy summed up [that] the assault landings would have to be made right in the heart of the city itself, where every structure provided a potential strong point of enemy resistance. Reviewing the Navy’s presentation, Chief of Naval Operations Adm. Sherman concluded by saying, ‘If every possible geographical and naval handicap were listed—Inchon has ’em all!’”

Army Chief of Staff General Joseph Collins believed that, even if the landings were a success, MacArthur would not be able to retake Seoul, and might even suffer a complete defeat at the hands of the NKPA in the embattled capital’s suburbs. The specter of an Asian Dunkirk thus loomed, with MacArthur in no doubt that he must first defend Japan, and only then Korea.

And what about the Japanese Home Islands? Might they not be attacked by their traditional enemy, the Russian bear, while MacArthur was tied down in Korea? And what, too, of the Red Chinese? Might they not also sweep down from the north and crush the X Corps like a paper cup and then go on to do the same to the 8th Army in the Pusan Perimeter? The risks that MacArthur was running were enormous.

Now it was MacArthur’s turn to answer his critics at the Dai Ichi military summit conference. “The bulk of the Reds,” he recalled saying, “are committed around Walker’s defense perimeter. The enemy, I am convinced, has failed to prepare Inchon properly for defense. The very arguments you have made as to the impracticabilities involved will tend to ensure for me the element of surprise, for the enemy commander will reason that no one would be so brash as to make such an attempt.

“Surprise is the most vital element for success in war. As an example, the Marquis de Montcalm believed in 1759 that it was impossible for an armed force to scale the precipitous river banks south of the then walled city of Quebec, and therefore concentrated his formidable defenses along the more vulnerable banks north of the city. But Gen. James Wolfe and a small force did, indeed, come up the St. Lawrence River and scale those heights.

“On the Plains of Abraham, Wolfe won a stunning victory that was made possible almost entirely by surprise. Thus, he captured Quebec and in effect ended the French and Indian War. Like Montcalm, the North Koreans would regard an Inchon landing as impossible. Like Wolfe, I could take them by surprise.”

Turning to the assembled sailors, he intoned, “The Navy’s objections as to tides, hydrography, terrain and physical handicaps are indeed substantial and pertinent, but they are not insuperable. My confidence in the Navy is complete, and in fact I seem to have more confidence in the Navy than the Navy has in itself! The Navy’s rich experience in staging the numerous amphibious landings under my command in the Pacific during the late war, frequently under somewhat similar difficulties, leaves me with little doubt on that score.”

Gen. Collins had proposed another landing at the west coast port of Kunsan instead, thus canceling MacArthur’s prized Inchon plan, but the latter was having none of it: “It would be largely ineffective and indecisive … an attempted envelopment that would not envelop. It would not sever or destroy the enemy’s supply lines or distribution center.… Better no flank movement than one such as this!”

After his conclusion, Admiral Sherman rose and said, “Thank you. A great voice in a great cause.” As for the dangers of going up Flying Fish Channel, Admiral Sherman snorted, “I wouldn’t hesitate to take a ship up there!” leading MacArthur to exclaim, “Spoken like a Farragut!”

A 45,000-To-One Shot

When MacArthur had earlier stated, “If we find we can’t make it, we will withdraw,” Admiral James T. Doyle retorted, “No, General, we don’t know how to do that. Once we start ashore, we’ll keep going.” Later, Admiral Doyle would recall the overall scene thus: “If MacArthur had gone on the stage, you never would have heard of John Barrymore!”

In his final remarks, MacArthur was even more firm: “We must strike hard and deep! For a five-dollar ante, I have an opportunity to win $50,000, and that is what I am going to do.” Indeed, almost no one except those on MacArthur’s immediate staff liked or backed the plan. General Ridgeway called it a 45,000-to-one shot.

Only three dates were possible for the attempted landing because of the moon: September 15, October 11, and November 3; characteristically, MacArthur chose the first, even though when President Truman and the Joint Chiefs of Staff approved Operation Chromite, there were only a mere 17 days to D-Day. Yet another problem was security—or the total lack of it—as South Korean President Syngman Rhee, General Walker, the American news media (which kept silent at MacArthur’s request), and even Red spies in Japan all knew of it and, later, an NKPA officer correctly predicted the landing in an official dispatch that was found after the battle.

Like Tsarist Marshal Mikhail Kutusov in Russia against the Napoleonic invasion of 1812, MacArthur’s basic strategy in these weeks was to buy time with space (the shrinking Pusan Perimenter) so as to build up his independent strike force and then smash the enemy in the rear at the time and place of his choosing, just as he had against the then-victorious Japanese Army in New Guinea in 1942.

To facilitate this, there was an unheard-of mobilization of troops and ships within Japan and the “mounting up” of Marines from all over the world, including American embassies, the U.S. Navy fleet in the Mediterranean, and the Marine Corps Reserve called up by the President to flesh out the needed muscle of MacArthur’s invasion armada. In the meantime, the beleaguered troops within the Pusan Perimeter kept buying the time needed in order for Chromite’s blow to assemble itself.

Chromite’s keys were simple: Land and secure the initial beachhead on the morning tide, land again in the evening with army troops and then, with the Marines, wage the land battle to defeat the surprised NKPA, cross the Han River, take Kimpo Airfield and then Seoul. After that, Walker would break out of the perimeter, link up with X Corps and drive the NKPA back to their frontier—and later beyond it.

The Marine “mounting out” or build-up from scratch, especially, was impressive, with the lst Marine Division rising in strength from 7,789 men in June when the North Korean invasion commenced, to 26,000 men by D-Day, Sept. 15, an unparalleled leap in mobilization, to use the term used by Lt. Gen. Lem Shepherd.

Marine Reserves flooded in from posts around the world and homes across the country. During four frantic days, August l to 5, nine thousand officers and men reported for duty. Lamented a Pentagon planner, “The only thing left between us and an emergency in Europe are the School Troops at Quantico [Virginia].”

The NKPA, too, were strengthening their forces and positions, however, particularly on Wolmi-Do Island astride Flying Fish Channel, the literal key to the overall success of Operation Chromite. Notes Robert Leckie, “Little Wolmi-Do guarded all the approaches to the inner harbor. It was well fortified. More, Wolmi rose 351 feet above water and was the highest point of land in the Inchon area. Its guns could strike at Marines attempting to storm the port’s seawalls to the north and south. Wolmi would have to be captured to secure the flanks of both landings, but before it could, Wolmi would have to be subjected to several days of bombardment by air and sea, and this, of course, would forfeit that advantage of surprise so necessary to MacArthur’s plan,” thus making the island fortress seemingly the very nemesis at the heart of Chromite’s hoped-for success.

As what was now being called “Operation Common Knowledge” proceeded, the later problem of the port of Inchon itself came into sharper focus as well. The Marines were concerned that they would be landing under fire directly into a city of 250,000 people where warehouses and buildings were fortified. In addition, once the port was taken, the Marines would have to regroup and prepare for the expected NKPA counterattack that might well drive them back into the water with heavy losses, much as had happened during the Canadian raid on Dieppe in Nazi-occupied France in 1942.

Surviving this, they would have to cross the wide and swift Han River before they could reach Seoul, the coveted prize. Not only the South Korean capital, Seoul was also the linchpin of the country’s telephone, telegraph, rail-way, and highway networks.

And what of the defenders? In Seoul there was the 10,000-man 18th Rifle Division, reinforced by the Seoul City Regiment, an infantry unit 3,600 strong. There was also the hated 36th Battalion, 111th Security Regiment, plus an antiaircraft defense force unit armed with Russian 85mm guns, 37mm automatic cannon, and 12.7mm machine guns, and air force personnel numbering in the thousands.

At Inchon was a garrison of two thousand new conscripts and two harbor defense batteries of four 76mm guns, each manned by two hundred gunners. In addition, Russian land mines were being laid, trenches and emplacements dug, and weapons and ammunition arriving. There were plans to mine the harbor, but the work had not begun.

Kimpo Airfield, too, was an extremely worthwhile military objective. Located to the north of the Inchon-Seoul axis, it lay a mile inland along the left bank of the Han River, downstream—or northwest—of Seoul. It was the best airfield in Korea, serving the two million inhabitants of Seoul as well as the port of Inchon.

Espionage played a significant part in the planning stages from the Navy side. Recalled Ridgway, “The first step in Operation Chromite was to scout the harbor islands which commanded the straitened Channel. A young Navy lieutenant, Eugene Clark, was put ashore near Inchon on Sept. lst and worked two weeks, largely under cover of darkness, to locate gun emplacements and to measure the height of the seawall. So successful were his efforts that he actually turned on a light in a lighthouse to guide the first assault ships into Inchon harbor before dawn on Sept. 15th.”

Even MacArthur saw the light on the way in to shore on the morning of the 15th: “I noticed a flash—a light that winked on and off across the water. The channel navigation lights were on. We were taking the enemy by surprise. The lights were not even turned off.” (Apparently, he never learned of Lieutenant Clark’s daring mission.) “I went to my cabin and turned in,” he concluded.

“All I fear is nature,” asserted Napoleon Bonaparte, and the Inchon invasion, too, was threatened by the sea and wind in the form of Typhoon Kezia, a 125-mile-an-hour storm that seemed destined to arrive precisely on time with Chromite’s Joint Task Force 7 invasion fleet in the Korean Strait. Naval planners nervously recalled the disastrous storm that had occurred during the invasion of Okinawa in the spring of 1945, and wondered if history might be repeating itself. MacArthur boarded his flagship the Mt. McKinley on the 12th. The vessel and its mates at sea were buffeted by howling winds and high seas when the storm suddenly veered north from the east coast of Japan on the 13th. But the worst of the terrible storm narrowly missed the invasion fleet.

As the countdown for Chromite approached, two diversionary bombardments took place by air to the south at Kunsan and to the north at Chinammpo, with the battleship USS Missouri blasting Samchok on the east coast right across from the real target, Inchon. Next came Wolmi-Do; beginning on Sept. 10 Marine Corsairs set most of its buildings afire.

By the 13th, the cat seemed to be out of the bag in the enemy camp: an intercepted Communist dispatch to Pyongyang read: “Ten enemy vessels are approaching Inchon. Many aircraft are bombing Wolmi-Do. There is every indication the enemy will perform a landing. All units under my command are directed to be ready for combat; all units will be stationed in their given positions so that they may throw back enemy forces when they attempt their landing operation.”

At last, 71,339 officers and men of the U.S. Marine Corps, Navy, Army, and ROK Marines were ready in their 47 landing craft to prove MacArthur either a seer or a reckless gambler who had bet on the wrong horse. According to one source, “Precisely at 0630, the U.S. Marines swept in from the Yellow Sea to face 40,000 North Korean troops.”

What would be the outcome—tremendous victory or ignominious defeat? In the event, the Battle of Inchon is most notable for two things: What didn’t happen that very well might have, and for the “about as planned” outcome that Douglas MacArthur had envisioned on that hill in South Korea just a short time before.

Did MacArthur Call It Right?

The initial landing force of the 3rd Battalion, 5th Marines, lst Marine Divsion clambered ashore from their landing craft and scaled the sea wall, securing Wolmi-Do Island in a mere—and historic—45 minutes. Stated Ridgway, “The action opened at dawn with a heavy bombardment by American destroyers, whose skippers gallantly steamed up the channel under the very muzzles of enemy cannons, and by British and American cruisers. The first task was to neutralize Wolmi-Do, the little island that sat right athwart the channel, with all channel traffic within point-blank range of its guns.

“The island, however, was not nearly so strongly fortified as had been feared [MacArthur had been right in this assessment] and its guns were quickly silenced by the naval bombardment. Marine Corsair planes strafed the island beaches … and the Marines stormed ashore, scattering the dazed defenders.… Artillery was positioned on the island then to support the assault upon the seawall.”

Continues Ridgway: “In places, the Marines used ladders to scale the wall, which stood four feet above the prows of the Landing Ship Tanks (LSTs). Elsewhere the LSTs simply rammed holes in the wall, or Marines opened holes with dynamite, through which the assault troops poured.… By dark the advance elements … were securely dug in on their beachhead ready to repel counterattacks,” which never came, so complete and total was the surprise victory.

And what of the man whose military genius had foreseen all this from the start? Aboard the Mt. McKinley, two NKPA MiG fighters were seen at 5:40 am beginning an attack on a cruiser to the front, leading General Courtney Whitney to alert MacArthur in his cabin of the danger. MacArthur simply said. “Wake me up again, Court, if they attack this ship,” rolled over and went to sleep.

After the bombardment began, he went to breakfast and then up on deck, commenting above the roar of the guns, “Just like Lingayen Gulf,” meaning his invasion of the Philippines in 1945. Later, Marine General Shepherd would recall, “His staff was grouped around him. He was seated in the admiral’s chair with his old Bataan cap with its tarnished gold braid [that Truman would mock a month to the day later] and a leather jacket on. Photographers were busily engaged in taking pictures of the General, while he continued to watch the naval gunfire—paying no attention to his admirers.”

“More People Than That Get Killed In Traffic Every Day!”

As the Marines had stormed ashore, elderly Korean civilians had gathered to watch them in awe, admiration, and relief at being liberated from their northern oppressors. The NKPAs also admired the Leathernecks, calling them “yellow legs” because of their distinctive leggings. Indeed, President Truman’s personal observer throughout the battle, National Guard Maj. Gen. Frank E. Lowe, also admired the men his boss had derisively called “The Navy’s police force,” leading the amphibious commander General Oliver P. Smith later to write, “As to personal danger, his claim was that the safest place in Korea was with a platoon of Marines.”

Back on the Mt. McKinley, MacArthur was told that there were 45 enemy POWs on Wolmi-Do, with U.S. losses being put at about six dead and 15-20 wounded, leading him to comment, “More people than that get killed in traffic every day!”

The landings were divided into a trio of Beaches: Green to take Wolmi-Do, and Red and Blue to seize Inchon proper, with the former to the north of the causeway linking Wolmi-Do to the port and the latter to the south of it.

The main battle assault was at Red Beach. In the words of one Marine company commander, Captain Frank I. Fenton, “It really looked dangerous.… There was a finger pier and causeway that extended out from Red Beach which reminded us of Tarawa, and, if machineguns were on the finger pier and causeway, we were going to have a tough time making the last 200 yards to the beach.”

At 5:24 pm the Marines went in, and Herald-Tribune reporter Marguerite Higgins described the scene: “A rocket hit a round oil tower and big, ugly smoke rings billowed up. The dockside buildings were brilliant with flames. Through the haze it looked as if the whole city was burning.… The strange sunset, combined with the crimson haze of the flaming docks, was so spectacular that a movie audience would have considered it overdone.” Cemetery Hill was taken, and Miss Higgins came in with the fifth wave onto Red Beach.

“We were relentlessly pinned down by rifle and automatic weapon fire coming down on us from another rise on the right [Observatory Hill]. Capt. Fenton’s men took it, and the CO himself had a rather unusual experience, as related by the late Marine Col. Robert Debs Heinl, Jr, whose seminal work Victory at High Tide: The Inchon-Seoul Campaign, is without doubt the very best study in print on MacArthur’s Cannae: “Outside his command post on the hill., Capt. Fenton stood poised to relieve himself by the light of a star shell. As he did so, the hole at his feet came alive and a frightened Communist soldier, armed with burp gun and grenades, sprang out and cried for mercy. Momentarily transfixed, Fenton shouted for his runner, who disarmed the drenched captive.”

The Indomitable “Chesty” Puller

Now came the taking of Blue Beach, and the re-emergence of one of the Marine Corps’ greatest all-time combat heroes: Colonel Lewis Burwell “Chesty” Puller, 52. “Fierce and utterly fearless,” wrote Colonel Heinl, “entitled to almost as many battle stars as the regiment he commanded. Winner of two Navy Crosses before World War II, and of two more during the war, Puller was one of the great fighting soldiers of American history. … Puller’s mission was to land south of Inchon and seize a beachhead covering the main approach to the city proper, from which the regiment could advance directly on [a fortress called] Yongdungpo and Seoul.

During one rather gloomy G-2 report, he cut his own intelligence officer short: “We’ll find out what’s on the beach when we get there. There’s not necessarily a gun in every hole! There’s too much goddamned pessimism in this regiment. Most times, professional soldiers have to wait 25 years or more for a war, but here we are, with only five years’ wait for this one.… We’re going to work at our trade for a little while. We live by the sword and, if necessary, we’re ready to die by the sword. Good luck! I’ll see you ashore.”

Notes his biographer, Burke Davis, Puller’s first wave went in at 5:30 pm. “Puller went to his objective at Blue Beach with the third wave, in a twilight hastened by the smoke pall, and climbed a 15-foot sea wall on one of the scaling ladders improvised on the ship en route. It occurred to him that the Corps had not used ladders since [the storming of] Chapultepec [in the 1848 Mexican War].

“He sat on the wall,” wrote Davis, “briefly watching the enemy in his front.” He settled his men in for the night, and launched his renewed attack inland the next day, Sept. 16 as planned, at dawn. “By 9 a.m., Puller had driven 4,000 yards against machinegun and mortar fire.” To the north, the fighting was sharper, with a counterattack by six Russian-made tanks against which the Americans launched aircraft. But the advance inland continued, the Marines taking care that none of their dead or wounded remained on the battlefield but were carried to the rear.

MacArthur—ever the military public relations man—had devised yet another masterstroke that paid off, a leaflet dropped some two hundred miles to the southeast, on the Red troops fighting at the Pusan Perimeter.

It read: “UNITED NATIONS FORCES HAVE LANDED AT INCHON. Officers and men of North Korea, powerful UN forces have landed at Inchon and are advancing rapidly. You can see from this map how hopeless your situation has become. Your supply lines cannot reach you, nor can you withdraw to the North. The odds against you are tremendous. Fifty-three of the 59 countries in the UN are opposing you. You are outnumbered in equipment, manpower and firepower. Come over to the UN side and you will get good food and prompt medical care.”

With nine American tanks on Wolmi-Do, three with flame-throwers, three with bulldozer blades, success was in the air. MacArthur took great satisfaction when he saw the Stars and Stripes flying overhead. Six NKPAs forced their officer to strip naked and then surrender, others jumped into the water and tried to swim to Inchon, and yet still others fought to the death in their holes in the ground.

The overall casualties at Wolmi-Do were 20 Marines wounded, with about 120 North Koreans killed and another 180 captured. MacArthur’s great gamble was looking good. After the fall of Inchon came that of Kimpo Airfield on the 17th—D-Day plus two. Two hundred NKPAs with five tanks were wiped out by the Marines in a battle six miles southeast of Inchon.

“Attack, push and pursue without cease,” had asserted French Marshal Maurice de Saxe, and now his 20th-century counterpart—MacArthur—came ashore to do precisely that, landing on the 17th and setting out in a jeep convoy to find the hero of the hour, Chesty Puller. But the tough Marine sent back the message: “If he wants to see me, have him come up in the front lines. I’ll be waiting for him.” MacArthur did so, and awarded Puller the Silver Star on the spot. Puller said, “Thanks very much for the Star, General. Now, if you want to know where those sons of bitches are, they’re right over the next ridge!”

The Marines had first fought in Korea in 1871, and first taken Seoul in 1894. Now—after taking fortress Yongdungpo and crossing the Han River, they took it a second time, on Sept. 26, but it wasn’t completely cleared of enemy resistance, after tough street-by-street, house-to-house fighting, until the 28th.

Indeed, the Soviet newspaper Pravda likened the battle for Seoul to the epic struggle at Stalingrad against the Germans in 1942-43: “Cement, streetcar rails, beams and stones are being used to build barricades in the streets, and workers are joining soldiers in the defense. The situation is very serious. Pillboxes and tank points dot the scene. Every home must be defended as a fortress. There is firing from behind every stone.

“When a soldier is killed, his gun continues to fire. It is picked up by a worker, tradesman or office worker. … Gen. MacArthur landed the most arrant criminals at Inchon, gathered from the ends of the earth. He sends British and New Zealand adventure-seekers ahead of his own executioners, letting them drag Yankee chestnuts from the fire. American bandits are shooting every Seoul inhabitant taken prisoner.”

That was on the 23rd. The day before, the NKPA troops had begun surrendering, as Colonel Heinl points out: “They started coming in in numbers, all carrying their burp guns. We stripped every one as he came in—pretty hard trying to get trousers off over leggings … (which the North Koreans, like their Marine captors, also wore). Indeed, in the two weeks after Inchon, MacArthur’s forces captured a stunning 130,000 North Koreans, just as predicted.

States Leckie, “By mid-September, the 70,000 combat troops opposing Gen. Walker’s combat force of 140,000 men [in the Pusan Perimeter] were served by perhaps 50% of the tanks and heavy weapons they needed. MacArthur’s estimate of what happened to an army at the end of a long supply line was proven correct, and his faith in what happened to it when it was put to rout was borne out with grim exactitude during the last 10 days of September.

“By the end of the month, the North Korean Army was shattered and fleeing north with little semblance of order. Some of the enemy’s 13 divisions simply disappeared. Their men were spread all over the South Korean countryside in disorganized and demoralized small parties. All of the escape routes were in United Nations hands, the sea was hostile to them and the sky roared with the motors of planes that spat death at them or showered them with firebombs.

“The roads, rice paddies and ditches of South Korea became littered with abandoned enemy tanks, guns and vehicles. Wholesale surrenders became commonplace.”

It was at this point and this juncture only—in the heady, warm glow of total victory by UN arms—that arose the idea of the unification of the two Koreas by force, especially espoused by President Rhee, who crowed, on Sept. 30, “What is the 38th Parallel?… It is non-existent. I am going all the way to the Yalu, and the United Nations can’t stop me.”

The Extent Of North Korean Atrocities Become Apparent

On Sept. 29, MacArthur and President Rhee wept together over the liberation of Seoul, as the General and the assemblage recited The Lord’s Prayer in gratitude for the UN victory, and the President blurted out through his tears, “We admire you. We love you as the savior of our race!” He would be overthrown in 1960.

The South Korean people had welcomed the incoming Marines with open arms, and had even brought out their small cooking stoves so that their liberators could warm their cold rations before eating. It soon became apparent why, as Communist atrocities began surfacing. Murdered American POWs also cropped up in ever-increasing incidents as UN forces advanced north into enemy territory.

The reckoning of the battle was also accomplished on Sept. 30, as—in the words of Colonel Heinl—“The X Corps War Diary rounded out the number of enemy killed at 14,000, his prisoners in hand, 7,000. These figures are about as correct as any that will ever be arrived at. Some 50 Russian tanks were destroyed, 47 by Marine ground or air. … The Marine division alone destroyed or took 23 120mm mortars, two 76mm self-propelled guns, eight 76mm guns, 19 45mm antitank guns, 59 14.5mm antitank rifles, 56 heavy machineguns, and 7,543 rifles.”

General MacArthur was not solely responsible for the great deed done in the campaign, Colonel Heinl concluded. He must be given credit for what Heinl calls “a masterpiece,” but he was responsible for the conception of Operation Chromite, not its command execution. For that the laurels must properly go to “the trinity of victory:” Admiral Struble, the overall commander of all forces afloat; Rear Admiral Doyle, the amphibious force commander; and General Oliver P. Smith, the landing force CO.

“Every great campaign spawns its statistics,” lamented Heinl. “To defeat the 30-40,000 defenders which the [NKPA] threw piecemeal against X Corps, 71,339 soldiers, sailors, Marines, airmen, and ROK troops landed at Inchon and bore their part in the battle. The cost of this victory to the United States was 536 killed in action or died of wounds, 2,550 wounded, and 65 missing in action. Among the Services, Marines, on the ground and in the air, paid the highest price.”

Adds Ridgway: “The measure of the role the ground forces played in Korea may be judged from the fact that, of the total U.S. battle casualties for the entire conflict, the Army and Marines accounted for 97%.… [But it] certainly may be said that the gallant airmen and sailors who contributed so much to the effort are nowhere more highly honored than in the hearts of the doughboys and Marines who fought the ground battles.”

Overall, Heinl asserts, “Inchon underscored … that America is a maritime power, that her weapon is the trident, and her strategy that of the oceans. Only through the sure and practiced exercise of sea power could this awkward war in a remote place have been turned upside down in a matter of days.”

He also makes this very astute observation: “Civil wars, Communist wars, and Asian wars are unhappily noted for their ferocity. The Korean War was all three … Not only did the NKPA cause the ruin of Seoul, but they stripped it systematically (as they did Inchon) of all usable industrial machinery and even office furniture, conducting such removals until the very last moment.”

Like Army man Ridgway, Marine Heinl notes, too, that Inchon was a joint inter-service victory, and quotes the words that are inscribed on the monument that stands today at Green Beach on Wolmi-Do and is still honored each year on Sept. 15 by the South Koreans (who “do not forget”):

Red Chinese Enter The Korean War

“The victory was not won by any one nation or any one branch of the military service. … The Inchon-Seoul operation was conducted jointly by the United States Army, Navy, Air Force, and Marine Corps.” The ROK forces, this writer feels, should be added to the inscription.

The victory had long-term effects that are still felt today, Heinl felt: “It revindicated amphibious assault (and, more fundamentally, maritime strategy) as a modern technique of war. In so doing, it almost unquestionably averted the abolition of the U.S. Marine Corps and naval aviation.”

The war went on, even though many thought it was won (on Oct. 30, 1950, one U.S. newspaper prematurely avowed that “Hard-Hitting UN Forces Wind Up War”). Less than a month later, Red Chinese Marshal Lin Piao launched his massive attack across the Yalu River from Manchuria into North Korea. “Two Chinese Army Groups—the Fourth, operating against Walker, the Third, against Almond [commanding the X Corps]—attacked with overwhelming force,” wrote MacArthur. “It was an entirely new war.”

Still, that was in the future, and even in the light of subsequent events, nothing can be taken from the bold stroke that both the enemy believed impossible of attempt and completely fulfilled its goal and prediction of cutting enemy supplies and reinforcements while at the same time putting him in a vise between two fighting forces.

General of the Army Dwight D. Eisenhower termed the victory “a brilliant example of strategic leadership,” while General Carl A. “Tooey” Spaatz called it “one of the most, if not the most, significant military operations in history.”

It was left to U.S. Navy Admiral “Bull” Halsey to say of the attack: “Characteristic and magnificent. The Inchon landing is the most masterly and audacious strategic stroke in all history.” In 1964, author David Rees in his work Korea: The Limited War, termed Inchon “A 20th Century Cannae, ever to be studied.”

And yet back in those bleak and desolate days of the summer of 1951, MacArthur himself was the first to realize that, in German Field Marshal Erwin Rommel’s words, “If I fail… everybody will be after my blood.” On the very eve of the landings he noted, “I alone was responsible for tomorrow, and if I failed, the dreadful results would rest on Judgment Day against my soul.”

A very well-researched article by Mr. Taylor. When was this originally written/published?