By Michael E. Haskew

Within days of Nazi Germany’s invasion of Poland on September 1, 1939, and the British declaration of war two days later, the vanguard of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) arrived on the continent of Europe. These four divisions grew to 150,000 men and more than 20,000 vehicles before reaching a peak strength of 400,000 by the fateful following spring.

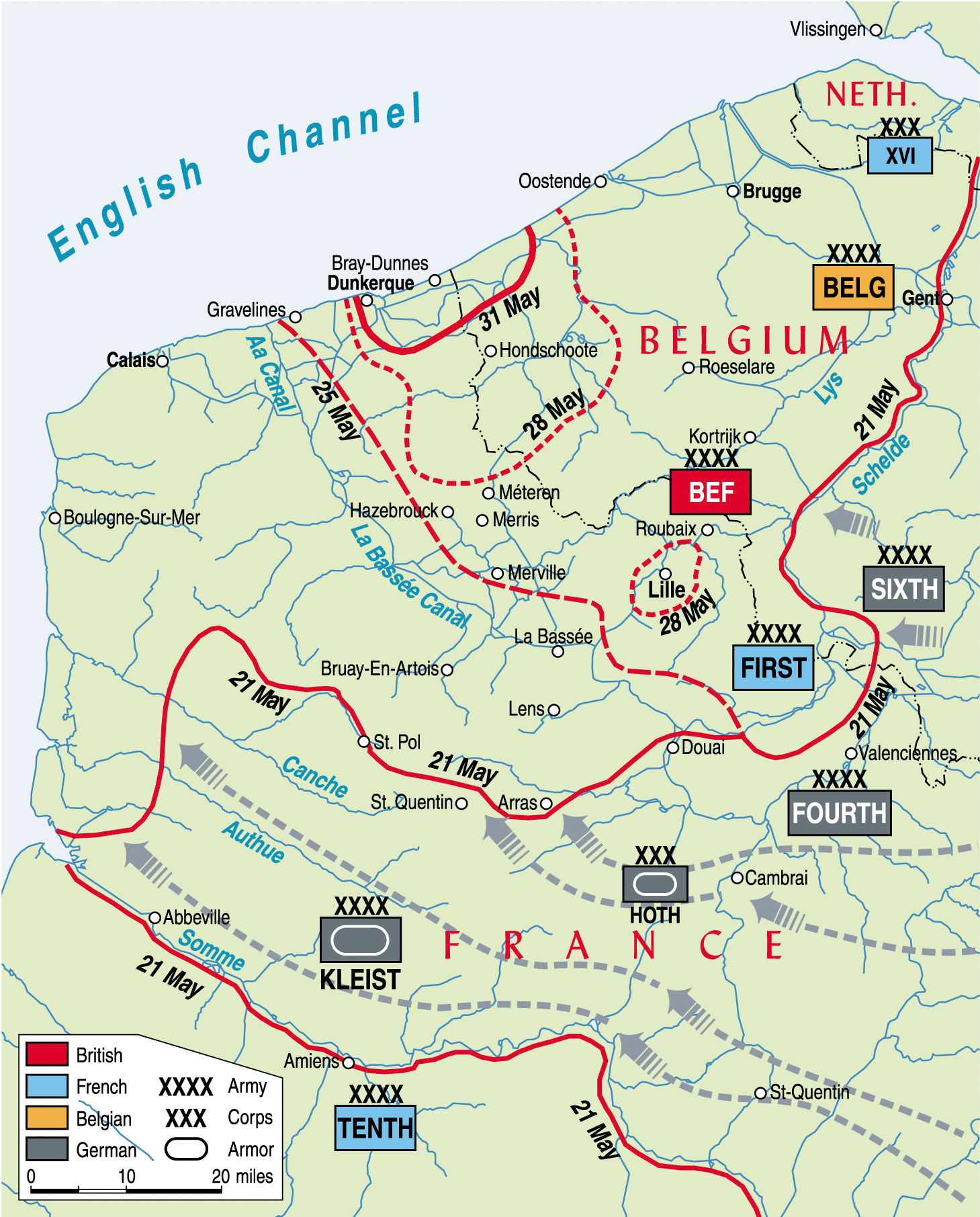

The marauding Nazis and their Soviet Red Army accomplices conquered Poland within weeks, but World War II in the West was strangely static. The lengthy period of inactivity as German and Allied forces sat idle along the frontier of France was derisively called the “Phony War.” However, it was not to last. On May 10, 1940, the Germans launched Fall Gelb, or Case Yellow, shattering the uneasy peace with an invasion of France and the Low Countries that swept to the English Channel and threatened to cut off and surround surviving French Army and BEF units.

The British commander, Field Marshal John Vereker, 6th Viscount Gort, consulted with French General Maxime Weygand, who’d replaced the ineffective General Maurice Gamelin, and as the French Ninth Army collapsed—exposing the British rear—Gort divided the BEF into two commands of roughly brigade size each and established a defensive perimeter called the Canal Line from the port of Dunkirk to the town of Arras, some 86 kilometers south. Gort realized that Dunkirk, located in a marshy area that might aid in its defense and near the longest uninterrupted beach on the Channel coast, was the closest port of adequate size with possibly intact harbor facilities, offering the best hope for any withdrawal of the remnants of the BEF or French armies from the continent.

An Allied counterattack at Arras from May 21-23 brought initial success against the Germans; however, early gains could not be sustained, and reinforcements were scarce. The advance ultimately ground to a halt. Nevertheless, the Germans were stunned by its ferocity and suspended offensive operations for an entire day.

Hitler later consulted with his lieutenants, and Reichsmarshal Hermann Göring, commander of the Luftwaffe, convinced the Führer that air attacks alone could finish off the Allied troops being squeezed into an ever-tightening perimeter around Dunkirk. Hitler’s decision to halt ground attacks and allow the Luftwaffe to deliver the coup de grace against the enemy hemmed in at the port ranks as one of his greatest blunders of World War II. By the time Hitler reversed course and resumed ground operations, the evacuation of Allied forces from Dunkirk was well underway.

While the bulk of the BEF, the remnants of three French armies, and a contingent of Belgian forces converged on the defensive perimeter at Dunkirk, heroic stands at the coastal cities of Boulogne, 60 kilometers southwest, and Calais, roughly half that distance from Dunkirk, bought precious time as a complex plan for evacuation came together. The 2nd Battalion Irish Guards and a single battalion of the Welsh Guards fought bravely at Boulogne, while the 3rd Royal Tank Regiment, three battalions of the Rifle Brigade, and approximately 800 French troops held on at Calais.

The defenders of Boulogne lost 400 killed in action but delayed the Germans for two days. At Calais, the soldiers of the 1st Searchlight Regiment, a non-combat unit, joined the fight as Allied troops rushed into the city just moments before the Germans arrived. Sacrificing themselves willingly, these Allied troops held on for three days. Calais fell to the Germans on May 26.

Meanwhile, the planning and execution of an epic seaborne rescue operation had begun.

As early as mid-May, 57-year-old Vice Admiral Bertram Ramsay had been aware of the predicament of the BEF and other Allied forces in France. As commander of the Royal Navy at Dover, Ramsay, who had joined the Royal Navy in 1898, served in World War I, retired in 1938, and been coaxed by Prime Minister Winston Churchill to return to service, was destined to command any evacuation effort undertaken on the continent. On May 20, from his command bunker deep beneath Dover Castle and chiseled into the famous white cliffs, Ramsay held his first planning meeting for the effort that came to be known as Operation Dynamo, named from the adjacent dynamo room that supplied electric power to the command bunker and headquarters facilities.

As Ramsay formulated Operation Dynamo, War Minister Anthony Eden assured Gort that arrangements would be made to attempt an evacuation. However, the temperament among the highest echelons of the British command was gloomy. General Sir Alan Brooke, commander of the BEF II Corps and future Chief of the Imperial General Staff, wrote a diary entry on May 23 that read like an epitaph. “Nothing but a miracle can save the BEF now and the end cannot be very far off … It is a fortnight since the German advance started and the success they have achieved is nothing short of phenomenal. There is no doubt that they are most wonderful soldiers.”

While the defenders of Boulogne and Calais fought on, Ramsay began to marshal as many Royal Navy vessels as possible for the evacuation and later called for every available ship that could carry at least 1,000 men. The British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) had already issued the following directive on May 14: “The Admiralty have made an Order requesting all owners of self-propelled pleasure craft between 30 feet and 100 feet in length to send all particulars to the Admiralty within 14 days from today if they have not already been offered or requisitioned.”

Although the order may in fact have been intended to appropriate such privately owned craft for harbor or shore patrol duties, it proved fortuitous. Such a practice was generally expected during wartime, and when the Dunkirk crisis arose at least some civilians were already poised to render cross-Channel assistance.

By May 25, Boulogne was in German hands, and the tanks of the 10th Panzer Division were slashing their way into Calais. The 1st Panzer Division was only 10 miles from Dunkirk.

Late on the following afternoon, Brigadier Claude Nicholson surrendered Calais to the Germans, and the British War Cabinet formally authorized Gort to concentrate his command around Dunkirk. Air Vice Marshal Keith Park, commander of Royal Air Force No. 11 Group, committed 16 fighter squadrons to provide some defense against Luftwaffe bombing and strafing.

As the BEF front contracted further toward Dunkirk, evacuating the industrial city of Lille, the resulting gap exposed the flanks of French and Belgian formations to the south, forcing a Belgian retirement that allowed the Germans to encircle the French 1st Army.

On May 27, British and French troops continued their withdrawal, and German panzer divisions renewed their attacks after Hitler lifted his ill-advised order to halt. Belgian formations were outflanked and forced to surrender. Within hours, King Leopold III agreed to Hitler’s demand for unconditional surrender, and Belgium was out of the war.

General Brooke rushed four divisions forward to plug a 26-kilometer gap that developed with the Belgian capitulation. Desperate fighting took place at Wytschaete and Poperinge during the next three days, but the BEF line held from the Belgian town of Ypres to the sea.

Responding to a War Department order, the Admiralty authorized Operation Dynamo at 6:57 p.m. on May 26. The idea was to evacuate up to 40,000 BEF soldiers, but the prospects seemed dim. However, Ramsay demonstrated coolness and command presence that soon turned a forlorn hope into a resounding success. He allowed subordinate officers to make crucial decisions on the spot, trusting their judgment.

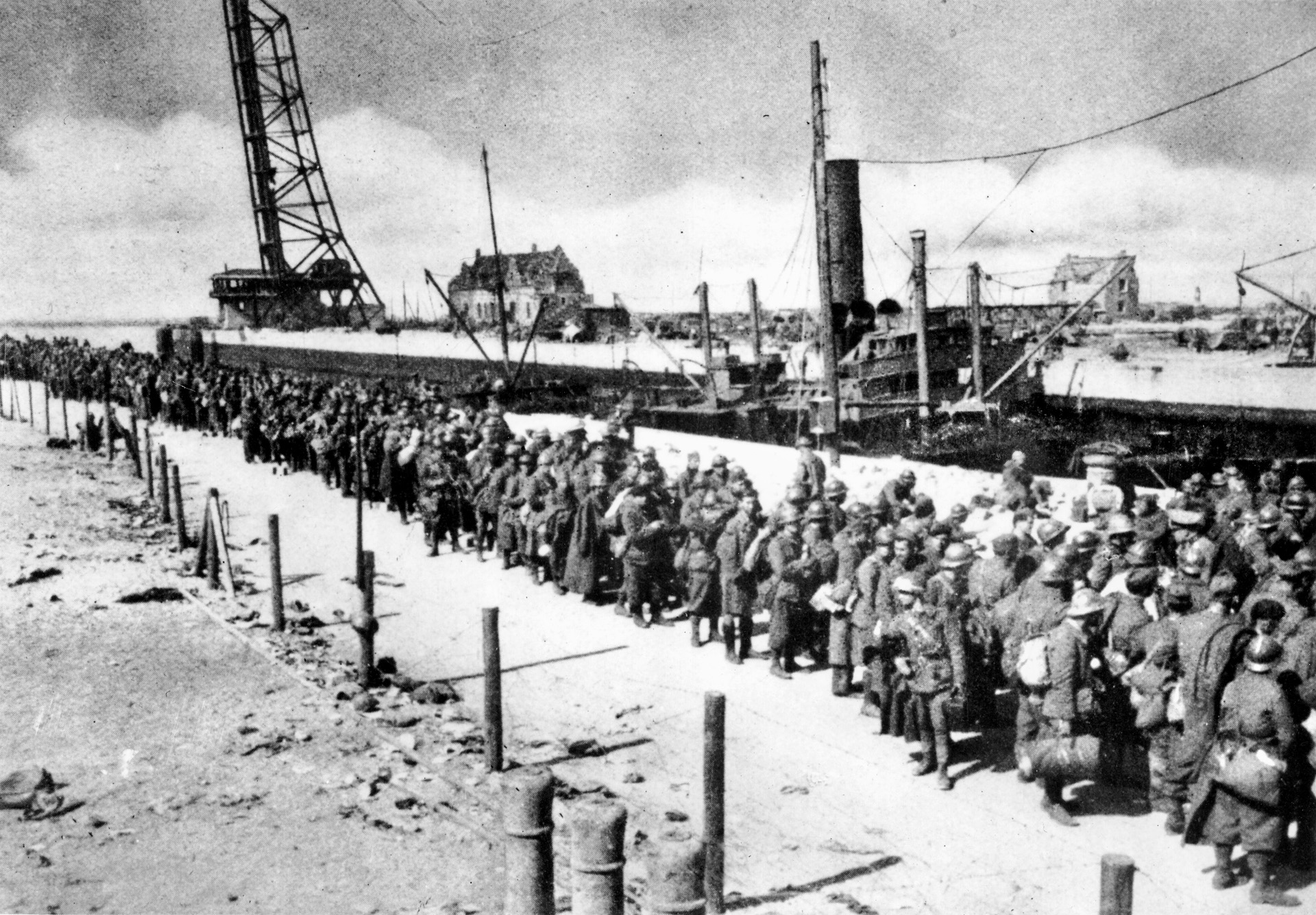

One of those who played a key tactical role in Operation Dynamo was Captain William George Tennant, an Admiralty staff officer who volunteered his services to Ramsay. Appointing Tennant as senior naval officer ashore at Dunkirk, Ramsay sent the officer to the combat zone on the afternoon of May 27. With an entourage that included a dozen officers and 160 sailors, Tennant boarded the destroyer HMS Wolfhound for the perilous passage. Harassed by German bombers for virtually the entire distance, the party arrived at 6 p.m.

Tennant later recalled that as he stepped ashore “the sight of Dunkirk gave one a rather hollow feeling in the pit of the stomach. The Boche had been going for it pretty hard; there was not a pane of glass left anywhere and most of it was still unswept in the center of the streets.” He reacted swiftly to a scene of growing chaos that might otherwise have gotten completely out of hand. Shore police were stationed along the beaches east of the city, discouraging roving bands of undisciplined soldiers from looting or deserting.

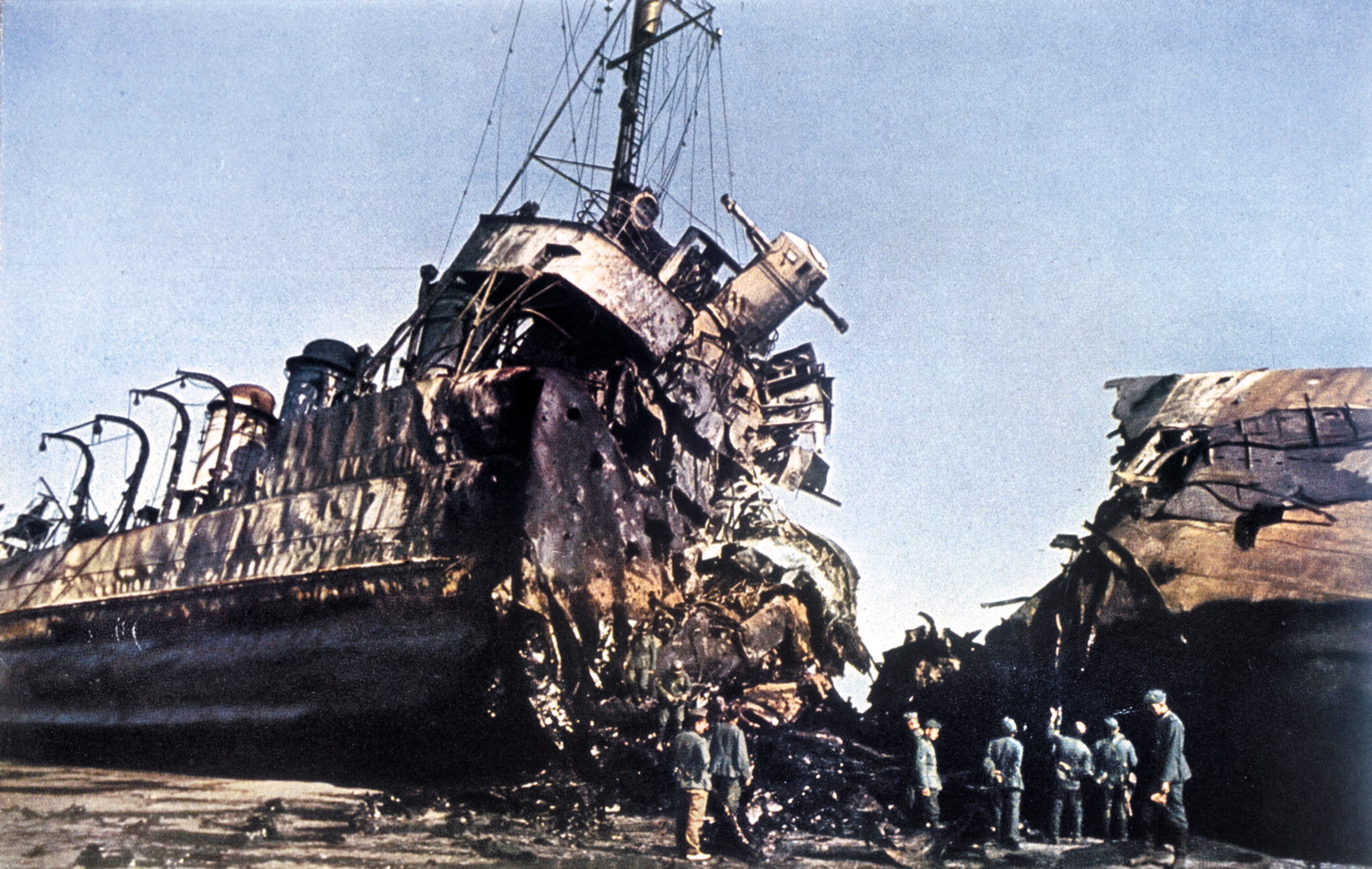

Subjected to severe Luftwaffe bombing and even artillery rounds from the German forces tightening the noose around the BEF neck, the Dunkirk port facilities were a shambles. It became clear that the best avenue of approach for the rescuing vessels would not be to sail into the harbor itself. The eastern beaches would have to do, Tennant thought. Two hours after his arrival, he radioed Ramsay, “Please send every available craft to beaches east of Dunkirk immediately. Evacuation tomorrow night is problematical.”

Fighting raged around the shrinking Dunkirk perimeter, and Luftwaffe air attacks intensified. Some ships sank outright or burned fiercely after hits from German bombs. Machine-gun bullets splashed trails in the sand and formed plumes in the water. Infantrymen swung their Enfield rifles skyward to take vengeful potshots at low-flying German planes.

By the night of May 27, the first 7,669 Dunkirk soldiers had been rescued. Tennant was acutely aware, however, that the pace of the evacuation was much too slow. Smaller boats had to make runs to shore, load troops, and ferry them to the larger vessels waiting in deep water. Complicating matters were the simple facts that despite the best efforts of RAF fighters, soldiers waiting on the open beaches were subjected to devastating Luftwaffe bombing and strafing, and the rescue vessels were also in great peril for prolonged periods.

In quiet desperation, Tennant scanned the wrecked harbor, shrouded in smoke, its buildings and facilities blazing. German aircraft had surely wreaked havoc, but they had failed to destroy the two long breakwaters, or moles, constructed of concrete pillars driven into the seabed with wooden boardwalks that were eight feet wide. They actually formed a manmade entrance to the harbor. At their originating points, the two moles were a mile apart. They converged toward one another as they jutted into the open sea.

Taking a closer look, Tennant believed that the moles might be used to embark groups of soldiers in an orderly fashion directly onto the larger rescue ships rather than utilizing only the time-consuming ferry process along the beach. He was disappointed to learn, though, that the West Mole, which extended only 500 feet, was surrounded mostly by shallow water—unsuitable for the deep draft of most larger ships. He decided against using it.

The East Mole, however, showed promise. Extending 1,400 yards toward the English Channel, it was anchored to the beach at the edge of Dunkirk proper near an area called Malo-les-Bains, a seaside resort. There were tall dunes nearby that might provide some cover for soldiers as they were grouped for their march down the East Mole and then, hopefully, directly aboard large ships that would carry them to Dover.

To test his theory, Tennant ordered the sleek, modern steamship Queen of the Channel, built in 1936 to ply the waters of the English Channel for the General Steam Navigation Company, to ease into the harbor and come alongside the East Mole. When the movement was completed, the inventive officer knew that he had a workable alternative to beach evacuation. The Queen of the Channel was later sunk by Luftwaffe bombers during Operation Dynamo, but by then she had rendered valuable service that ultimately saved thousands of Allied lives.

Just after 4:30 a.m. on May 28, Tennant informed Ramsay that a change in procedure would reap great benefits. He asked those large rescue ships that were standing offshore waiting for loads of evacuees, particularly the fast Royal Navy destroyers that were available, to be redirected to tie up at the East Mole.

Throughout the day, the rescue effort continued. As Operation Dynamo developed, Prime Minister Churchill was briefed regularly on its progress. As the day wore on, 11,874 soldiers were evacuated from the harbor, most of them from the East Mole. Another 5,930 had been plucked from the eastern beaches, still in use. At Lille, 40,000 soldiers of the trapped French First Army held on against seven German infantry and panzer divisions. Their grim determination until the end of May occupied substantial German forces that might have smashed the Dunkirk beachhead otherwise.

Perhaps by this time Hitler had realized his error in halting the ground assault and providing a window of opportunity for the British to further organize Operation Dynamo. While German Intelligence confirmed on May 27 that the evacuation effort had begun, Admiral Otto Schniewind, a high-ranking Kriegsmarine staff officer, noted in a conversation with Göring that the opportunity to annihilate the BEF was slipping away.

“A regular and orderly transport of large numbers of troops with equipment cannot take place in the hurried and difficult conditions prevailing,” Schniewind told the pompous Reichsmarshal. “Evacuation of troops without equipment, however, is conceivable by means of large numbers of smaller vessels, coastal and ferry steamers, fishing trawlers, drifters, and other small craft, in good weather, even from the open coast.”

Indeed, the Allied troops that evacuated from Dunkirk had lost nearly all of their personal kit, and heavy equipment lay in abandoned clusters along the beaches and in the town. Still, saving the soldiers was the primary objective. Time was of the essence, and there was no guarantee that those stout soldiers manning the perimeter could hold out much longer.

But the boats kept coming—not just the Royal Navy, but watercraft of every description, even sailing ships and dinghies. Many of these were manned by civilians who’d left the safety of England to run the gauntlet to Dunkirk. Arthur D. Divine was among them, and he later remembered, “It was the queerest, most nondescript flotilla that ever was, and it was manned by every kind of Englishman, never more than two men, often only one, to each small boat….

“It was dark before we were well clear of the English coast,” he continued. “It wasn’t rough, but there was a little chop on, sufficient to make it very wet … When destroyers went by, full tilt, the wash was a serious matter to us little fellows. We could only spin the wheel to try to head into waves, hang on, and hope for the best.”

Thanks to the command and organizational skill of Admiral Bertram Ramsay, the quick thinking of Captain Tennant, and the incredible bravery of many soldiers who gave their lives so that others might survive the debacle of defeat, Operation Dynamo was proceeding.

As daylight ebbed on May 28, 1940, there was a glimmer of hope that the results of the rescue effort would exceed even the most optimistic expectations. However, in the face of a mighty enemy, the issue remained very much in doubt.

From the outset, Operation Dynamo was fraught with peril, but the seaborne evacuation continued despite staggering losses and heavy German resistance.

Each of the three routes plotted for the evacuating ships of the Dunkirk rescue operation to follow presented its own hazards. Designated routes X, Y, and Z, they were each used at various times and required steely nerves for those who undertook the effort, sometimes using buoys and light ships as reference points. Route X, opened on May 29, ran 102 kilometers, first north and then northwest from Dunkirk, then taking a sharp turn southwest toward Dover. Route X was generally secure from attack by enemy ships or planes once the coastline was cleared, but minefields and shoals made it treacherous for use at night.

Route Y was by far the longest at 161 kilometers, edging northeast from Dunkirk before turning sharply west and then south to Dover, crossing the paths of German U-boats and patrolling aircraft. Its travel time to Dover was four hours longer than the most direct course, 72-kilometer Route Z, which ran west from Dunkirk with a lengthy period in range of German artillery on the French coastline before a gradual northwesterly turn reached Dover.

The Royal Navy was taking a dreadful pounding, and on May 29 alone the destroyers Grafton, Grenade, and Wakeful were sunk while six others were damaged, and six merchant ships involved in the operation went down in the harbor. Wakeful was hit by a pair of torpedoes from the German E-boat S-30 that morning, and only one of 640 Allied soldiers aboard survived the sinking along with just 25 of the destroyer’s complement of 110 sailors. When Grafton attempted to render assistance to Wakeful, a torpedo from the submarine U-62 ripped into her stern, killing 15 men including the captain. Grafton was wracked by a violent secondary explosion, and another destroyer, Ivanhoe, sank the hulk with gunfire.

HMS Grenade prepared to cross the English Channel to Dunkirk during the night of May 28. The destroyer was set upon by German Junkers Ju-87 Stuka dive bombers, screaming down in near-vertical dives through a hail of antiaircraft fire. Three German bombs set the destroyer ablaze, killing 14 sailors outright and mortally wounding four more. Fears that the destroyer might sink at the East Mole and block the approaches of other ships prompted orders to cast off.

Alongside Grenade, the destroyer Jaguar was hit by a bomb that killed 13 and wounded 19. The minesweeper HMS Waverly, with 600 soldiers packed aboard, took bomb hits and sank rapidly, losing about 350 men. Amid the chaos, the HMS Comfort was fired upon by friendly ships and rammed by the minesweeper HMS Lydd, killing four men.

Grenade drifted into the harbor channel and was taken in tow by the trawler John Cattling. As the destroyer lay derelict on the edge of Dunkirk’s outer harbor, her magazines exploded, and the shattered warship sank during the night.

Although grievous naval losses had been expected, such a rate of attrition was both shocking and unsustainable. The following day, the Admiralty issued orders for all its newest destroyers to clear the vicinity of Dunkirk. Only 18 destroyers, most of them of World War I vintage or older, remained on station.

While the lethal air-sea duel continued on May 29, another 33,558 Allied soldiers reached safety in England.

As the Dunkirk defensive perimeter continued to shrink, Gort worried that German artillery fire might force a suspension of the evacuation effort, but operations continued despite the ongoing threat and the devastating Luftwaffe raids.

Before he would authorize ships to use Route X, Admiral Ramsay ordered minesweepers into the area to clear as much of that hazard as possible, while three Royal Navy destroyers ventured within range of any German artillery that might blast away at evacuating vessels to

determine the extent of that threat. Luftwaffe dive bombers attacked the destroyers but scored no hits, and there was no appreciable artillery fire. By the afternoon of the 29th, Route X was open.

French destroyers and Dutch ships joined the evacuation and helped quicken its pace, while both the East Mole and the beach were still being utilized. Across the English Channel, the port of Dover teemed with activity as 25 Royal Navy destroyers, 16 motor yachts, 12 Dutch skoots, four hospital ships, and more than 20 other vessels moved through the harbor that day.

The experience of Arthur D. Divine, one of many volunteer seamen who braved the gauntlet of enemy fire during Operation Dynamo, is representative of the fortitude they displayed. “Even before it was fully dark, we had picked up the glow of the Dunkirk flames ….” he wrote. “The aircraft started dropping parachute flares. We saw them hanging all about us in the night, like young moons. The sound of the firing and the bombing was with us always, growing steadily louder as we got nearer and nearer … The beach, black with men, illumined by the fires, seemed a perfect target, but no doubt the thick clouds of smoke were a useful screen.

“The picture will always remain sharp-etched in my memory,” Divine continued, “the lines of men wearily and sleepily staggering across the beach from the dunes to the shallows, falling into little boats, great columns of men thrust out into the water among bomb and shell splashes …. As the front ranks were dragged aboard the boats, the rear ranks moved up, from ankle deep to knee deep, from knee deep to waist deep, until they, too, came to shoulder depth and their turn … The little boats that ferried from the beach to the big ships in deep water listed drunkenly with the weight of men…. And always down the dunes and across the beach came new hordes of men, new columns, new lines.”

The ordeal of retreat, incessant bombardment, and finally salvation took its toll on the suffering soldiers of the BEF. Sam Kershaw, a private in the 42nd East Lancashire Division, remembered, “We were fighting in northern France when a German armored column caught up with us and sprayed the whole unit with gunfire. We sheltered from the gunfire in a ditch and lost all our equipment. When we got away from the German column our officer said we had to make our way to Dunkirk, where we were going to be evacuated.”

The trek took 48 hours, mostly on foot. “When we got there, I laid down in the sand, tired and starving, and went to sleep,” recalled Kershaw. “We waited in some nearby sand hills all of the next day and when night fell we were taken in a rowing boat to HMS Halcyon (a Royal Navy minesweeper). I fell asleep on deck, and when I awoke I saw the white cliffs of Dover in front of me.”

As the embarkation process was repeated on the beach and at the East Mole, it achieved a measure of remarkable efficiency. Canadian-born Commander James Campbell “Jack” Clouston served as pier master at the East Mole, enforcing discipline strictly, sometimes at the point of his revolver. Under Clouston’s direction, 600 men could be loaded aboard a ship in as little as 20 minutes.

Clouston had been in command of the destroyer HMS Isis and was temporarily assigned to Captain Tennant’s shore party headed for Dunkirk while his ship was undergoing repairs. Soon after arriving, Tennant’s officers cut cards to determine their assignments during the evacuation. Clouston drew the East Mole and discharged his duties with composure for the next five days and nights.

On June 1, Clouston returned to Dover to deliver a report to Admiral Ramsay. The next day, Clouston and 30 other men boarded two RAF motor launches for the trip back to Dunkirk. As they neared the coast of France, the launches were set upon by eight Stukas. When his launch was sunk, Clouston ordered the other boat to continue on its way. Rescue never came, and the hero of the East Mole died of hypothermia. Only one survivor of his launch was pulled from the Channel.

Although Tennant would retain command as senior naval officer ashore at Dunkirk, the Admiralty decided to dispatch Rear Admiral William Frederic Wake-Walker to take charge of all ships operating off the French-Belgian coastline. Wake-Walker arrived off Dunkirk on May 30 aboard the minesweeper HMS Hebe. In short order, he joined the lengthening list of Operation Dynamo’s stalwarts, rendering yeoman service.

When he discovered that the modern Royal Navy destroyers had been withdrawn due to heavy losses sustained the previous day and only 15 older destroyers remained at his disposal, Wake-Walker went directly to Ramsay with his request for the return of new destroyers to the Dunkirk area. Ramsay, in turn, went to the Admiralty and held sway. Soon, seven new destroyers were back in the fight.

Despite the absence of the modern destroyers, May 30 proved to be the most productive day yet for Operation Dynamo. A total of 53,823 BEF and French soldiers were evacuated, while Allied troops continued to trickle toward the coast. Billowing clouds of smoke obscured the beaches and the East Mole from German air attack for much of the day, while seven of the older destroyers managed to board 1,000 soldiers each and sail for England unmolested. Six British vessels, including two old destroyers, were damaged by German bombs, while the French destroyer Bourrasque struck a mine and was later sunk by German artillery fire with heavy loss of life.

All the while, the Royal Air Force (RAF) and the Luftwaffe battled for control of the skies above the English Channel, and each paid a high price. Great damage was inflicted on the British relief flotilla, but the Luftwaffe lost scores of aircraft shot down during a strenuous week of combat. German losses have been estimated at 132 planes during the air battles above Dunkirk; however, many historians believe this count is significantly lower than the actual number. RAF losses during the critical period reached a shocking 177.

Many British soldiers at Dunkirk grumbled about the absence of the RAF. Believing that German fighters and bombers had been allowed to bomb and strafe at will, they were bitter. Of course, their perception of the role the RAF played in Operation Dynamo is at least somewhat misguided.

While the Royal Navy, Army, and civilian participants gave full measure at Dunkirk, the mission of the RAF was no less daunting. The Battle of France had substantially depleted British fighter strength on the European continent. Actually, a French plea for more British planes was summarily rejected because RAF Fighter Command realized that the shortage of Hawker Hurricane and Supermarine Spitfire fighters was acute. It was imperative that a reasonable number of fighters, particularly the sleek, modern Spitfires, be held in reserve should the Luftwaffe launch an all-out air campaign against Britain itself—possibly even in preparation for an invasion of the British Isles.

In the event, Fighter Command did commit large numbers of aircraft to the battle above Dunkirk. They patrolled the English Channel to interdict Luftwaffe raids against troop-laden ships and engaged in dogfights with German fighters that would otherwise be machine-gunning soldiers exposed on the beaches below. RAF fighters also intercepted German bombers on their way to attack Dunkirk. During these missions, it was preferable to engage the enemy as far from the beaches and harbor as possible, preventing the Stukas and Heinkel He-111s from dropping their deadly cargoes at all. These engagements often took place at high altitudes, out of the sight and hearing range of the suffering soldiers of the BEF. Throughout Operation Dynamo, the RAF flew 4,822 air sorties, hardly an absentee performance.

Among the RAF heroes of Operation Dynamo was Squadron Leader Brian “Sandy” Lane, a daring Spitfire pilot who had joined the RAF in 1936 to escape a dead-end factory job. Lane assumed command of No. 19 Squadron after its previous commander was shot down. His leadership was exceptional, and one squadron mate recalled, “He was completely unflappable, no matter what the odds, his voice always calm and reassuring, issuing orders which always seemed to be the right decisions.”

Lane received the Distinguished Flying Cross for his service during Operation Dynamo, and his superiors judged his pilot rating as “excellent.” Sadly, he did not survive the war. In December 1942, during a fighter sweep over Holland, he was attacked by several Me-109s and not heard from again. The intrepid pilot was 25 years old.

By May 31, the rescue operation had progressed to the extent that the number of British troops around Dunkirk had dwindled to a fraction of its peak some five days earlier. Prime Minister Churchill and War Minister Eden were well aware that the capture of such a high-ranking Army officer as Lord Gort could not be permitted, but as the Dunkirk defensive pocket contracted its ability to fend off German attacks would inevitably be compromised.

On the 31st, Gort, General Alan Brooke—whose brilliant leadership of British ground troops had contributed greatly to the success of Operation Dynamo—and General Oliver Leese, Deputy Chief of Staff of the BEF, were evacuated. The remaining British soldiers in France were placed under the command of General Harold Alexander.

High winds swept smoke and haze away from the vicinity of Dunkirk, revealing fresh targets for German aircraft and artillery, and the beaches were temporarily closed to small boats. German ground forces compelled the British defenders to abandon La Panne, the furthest east of the Dunkirk beaches. The thin perimeter shrank to a depth of only five

kilometers. Despite the hazards, a peak number of 68,014 men were evacuated on May 31, with 22,942 of these taken from the beaches and 45,072 from the East Mole. In five days, 194,620 men had been safely brought to England.

In exchange, the Royal Navy destroyers Express, Icarus, Keith, and Winchelsea were damaged by German bombs on May 31, but continued their assigned duties. Express, a minelaying destroyer commissioned in 1934, made runs between Dunkirk and Dover, decks packed with rescued soldiers. Along with the destroyer HMS Shikari, Express was the last Royal Navy ship to exit Dunkirk harbor at the conclusion of Operation Dynamo on June 4. Swift, deadly German E-boats torpedoed the French destroyers Cyclone and Scirocco, later sunk by German bombers with the loss of 59 seamen and 600 soldiers.

Bernard Stums of the BBC watched for a while as beleaguered ships and men of Operation Dynamo made landfall in England. “At dawn this morning, I stood on the quays of a south coast port … and I saw several ships coming in and every one of them was crammed full of tired, battle-stained and bloodstained British soldiers. Soon after dawn I watched two warships steam in, one listing heavily to port under the enormous load of men she carried on her deck.

“In a few minutes, her tired commander had her alongside, and a gangway was thrown from her decks to the quay,” Stums continued. “Transport officers counted the men as they came ashore. No question of units, no question of regiments, no question even of nationality, for there were French and Belgian soldiers who had fought side by side with the British in the battle of Flanders ….”

From June 1-4, 1940, the greatest sealift evacuation in military history concluded. The incredible rescue of thousands of soldiers of the BEF and Allied troops from the beaches and the harbor of Dunkirk remains one of the great wartime epics in human history. For more than a week, vessels of every description, warships of the British Royal Navy and the French Navy, little boats pressed into service and some of them manned by British civilians, Dutch fishing boats and trawlers, and Belgian and even Polish watercraft ferried thousands of fighting men, who otherwise would have died or languished in German prison camps, to safety.

The success was buoyed by several factors, including the heroism of the British and French soldiers who valiantly sacrificed themselves in rearguard defense of the beachhead, the relentless determination of Royal Navy and Royal Air Force (RAF) personnel who bravely dodged Luftwaffe bombs and took on enemy fighter planes, and the contributions of civilians in the little ships and at the receiving ports of Dover and other points such as Ramsgate and Margate.

By June 1, Operation Dynamo had been in full swing for five days, evacuating men in daylight when it was possible and through the night at times. Still, the soldiers came down to the dunes and waited in the water or shuffled to the East Mole for loading aboard the packed decks of ships of every description. The operation reached its climax during the next 72 hours, but these were hard days indeed.

Rear Admiral Wake-Walker stood on the bridge of the destroyer HMS Keith on the morning of June 1. His concerns were significant—including responsibility for the safe passage of Lord Gort from the continent to England and maintaining the pace of the continuing evacuation. Lord Gort left HMS Keith in the early morning hours and reached London later in the day.

Captain D.J.R. Simson, Keith’s skipper, had been killed when mortar and small-arms fire raked the destroyer as it swept in to blast enemy artillery positions during the defense of Boulogne several days earlier, and on the morning of June 1, Keith was under the command of Captain E.L. Berthon, who had directed accurate gunfire against German artillery positions around Dunkirk throughout the previous day.

With Gort gone, Wake-Walker turned to other business, but the Luftwaffe interrupted. Just after sunrise, several enemy fighters appeared in the distance and made strafing runs across the beach. Soldiers scattered for cover and returned to their places in orderly fashion when the immediate threat had passed. By 8 a.m., the crew of HMS Keith had already fought off one attack by German dive bombers, but soon enough the Stukas returned with a vengeance.

Four lines of Luftwaffe dive bombers, numbering perhaps 60 gull-winged Stukas, plummeted from numerous points on the compass. Aboard the targeted Keith, Seaman Ian Nethercott watched with a strange mixture of awe and terror. “I just suddenly saw this Stuka appearing over the bridge—it seemed to be almost touching it—and this great big bloody yellow bomb fell from its clamps. It was a thousand pounder …. We were moving to starboard, and he dropped it down the port side. It didn’t land on us, but it blew a part of the port side in.”

While sailors hammered away at the raiders with 2-pounder antiaircraft guns and anything else that would point skyward, another bomb detonated just aft of Keith’s stern, jamming the helm and leaving her turning helplessly in a circle. A third bomb fell straight down the destroyer’s second funnel, exploding in the No. 2 boiler room, snuffing out all power and killing everyone in the vicinity. The destroyer dropped anchor, and the order to abandon ship was given.

Wake-Walker transferred his flag temporarily to the swift motor torpedo boat MTB-102, which may well have become the smallest Royal Navy vessel in history to actually serve as an operational flagship. It was apparent that Keith was doomed, and the Admiralty tug St. Abbs pulled close to evacuate 130 survivors, including several members of Gort’s staff who were still aboard. Thirty-six sailors were already dead, but compounding the tragedy, St. Abbs was set upon by Luftwaffe bombers later in the day and sunk, taking 100 former Keith crewmen to their graves.

Keith was not alone among the Royal Navy casualties on that bloody June 1. The destroyer HMS Basilisk was sunk with nine sailors killed. The destroyer HMS Havant took two bombs in her engine room while another detonated beneath the hull, killing eight crewmen and at least 25 soldiers on deck. Havant was so thoroughly damaged that the minesweeper HMS Saltash removed the crew and scuttled the burning hulk.

The minesweeper HMS Skipjack had taken 275 soldiers aboard when 10 Junkers Ju-88 twin-engine bombers swept in to drop three bombs on the small vessel. Skipjack capsized just before 9 a.m., remained afloat for about 20 minutes, and then plunged to the bottom of the harbor with many of the soldiers aboard trapped beneath the hull. Most of them died, along with 19 sailors, and Luftwaffe aircraft reportedly strafed the survivors in the water.

Two miles off Dunkirk at midday, the French destroyer Foudroyant was attacked by Stukas and Heinkel level bombers. Three 250-kilogram bombs hit the ship, breaking her keel. She rolled over and sank in 25 meters of water, and 19 of her crew were killed. Fortunately, since Foudroyant was inbound to Dunkirk, her decks were not crowded with rescued soldiers.

These morning losses were appalling. At 1:45 p.m., Admiral Ramsay ordered all destroyers out of the combat zone. Incredibly, a total of 64,429 soldiers were evacuated on June 1, including 47,081 at the East Mole and 17,348 off the beach. The steamer Whippingham had transported 2,700 men to safety singlehandedly. The little boats that dashed to the beaches on that harrowing Saturday had pulled an average of 280 men per hour from every mile of beach that remained in Allied control.

While Dover handled primarily larger ships, the smaller craft were busily swarming in and out of Margate and Ramsgate and other points. By midmorning on June 1 alone, Ramsgate had received 24 small vessels with 4,356 evacuees aboard. When Operation Dynamo concluded, more than 43,000 rescued soldiers had come ashore there. While estimates of the number of Allied ships participating in the sealift peak at about 900, some sources relate that more than 600 of these were counted among the fabled “little ships.”

One of the little ships belonged to Charles Lightoller, who 28 years earlier had served as 2nd Officer aboard RMS Titanic and survived the sinking of the great passenger liner on April 15, 1912. Lightoller took his personal motor yacht Sundowner to Dunkirk on June 1 and returned with more than 100 soldiers. Sundowner was restored in 1990 and is today on display at Ramsgate.

As Ramsay issued his recall order to the embattled Royal Navy destroyers and other warships off Dunkirk, Lord Gort arrived at Downing Street in London. Churchill congratulated the commander on his skillful defensive retreat and the success of the ongoing evacuation, which would actually save the core of the British Army to fight another day.

During the 45 minutes that followed, Gort described the operations of the BEF in some detail. Former Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain later wrote, “Gort got back this morning and gave us a thrilling account of the whole operation. There seems to have been hardly any mistake that the French did not make ….”

Of course, the Battle of France was ongoing, and there would be more time later for an assessment of command and troop performance. At the time, however, it must be acknowledged that French troops, particularly those of the XVI Corps, were fighting valiantly to hold the perimeter at Dunkirk. For example, from May 29 to June 4, the 12th Motorized Infantry Division committed its 8,000 soldiers to the effort with orders to “…hold your present position at all costs to the last man and last round. This is essential in order that a vitally important operation can take place.”

As the rescue effort progressed, concerns arose within the beleaguered French government that British soldiers were actually being evacuated in much larger numbers than French troops. French Prime Minister Paul Reynaud and Churchill had already discussed the situation during an earlier meeting.

By June 2, only about 4,000 soldiers of the BEF rear guard and a considerably larger number of French troops remained ashore in the vicinity of Dunkirk. However, the losses sustained on June 1 compelled Ramsay to suspend all rescue operations at 7 a.m. with the hope of resuming after dark. Earlier plans to conclude Operation Dynamo by first light on June 2 were discarded, and the evacuation window would remain open at least another 24 hours.

With the bulk of the BEF already out of France, a total of 26,256 men were removed from the beaches and the East Mole on the 2nd. As the day wore on, the remaining British soldiers filtered through the perimeter held by the fighting French. Then, deliberately and resisting German pressure to the best of their ability, the French began their own retrograde movement.

June 2 was Sunday, and a British chaplain conducted services on the beach, including Holy Communion. German aircraft flew in to bomb and strafe, interrupting the services five times, but the chaplain persevered until the services were concluded.

As the sun rose on June 2, RAF Spitfires and Hurricanes took off from airfields in southern England on dawn patrol. Scanning the skies over the Channel coast for German planes, they found few. Most of the pilots turned for home—and breakfast—without firing their guns.

A short time later, however, pilots of Nos. 66, 92, 266, and 611 Squadrons, perhaps flying as many as 50 RAF fighters, were back in the air. Twenty-three-year-old Flight Lieutenant Robert Stanford Tuck led the big flight. Around 8 a.m., he pressed an attack against three He-111 bombers.

Out of nowhere, several German Messerschmitt Me-109 fighters jumped the young pilot. Machine-gun bullets chewed into the tail section of his Spitfire, but Stanford Tuck turned the tables and sent one enemy fighter spinning out of control. He then turned back toward an He-111, shot it down, and watched the crew’s parachutes billow. During another brief brawl with Me-109s, Stanford Tuck damaged two of the enemy planes. Within the hour, he was safely on the ground at his home field, RAF Martlesham.

The RAF tally that morning included 14 Luftwaffe planes shot down and 21 more damaged. However, Stanford Tuck’s command sustained grievous losses, as well. Five pilots were killed in action. Five others were shot down and survived, one of them taken prisoner. Two of the dead pilots, Ken Crompton and Donald Little from No. 611 West Lancashire Squadron, were newlyweds, both in their early 20s.

While their husbands fought and died in the skies over Dunkirk, the 19-year-old brides of Crompton and Little were attending a breakfast given by the squadron commander for those wives whose husbands had previously lost their lives. As those gathered somberly sipped champagne, word reached these two that they were now widows as well.

Late on the morning of June 2, Ramsay signaled, “The final evacuation is staged for tonight, and the Nation looks to the Navy to see this through ….” Under cover of darkness, the last of the organized BEF rear guard boarded boats and departed the embattled coast of France. As many as 20,000 French troops expected to reach the evacuation area failed to appear due to command and logistics issues in the face of continuing German pressure.

At 11:30 p.m., Ramsay received the message, “B.E.F. Evacuated. Returning now.”

Tennant used a megaphone to shout for any remaining British soldiers. Finally satisfied that the job was complete, he radioed Ramsay at 10:50 a.m. on June 3, “Operation completed; returning to Dover.” In reality, there were still well over 100,000 British troops in France. Among these was the 51st Highland Division, detailed to support the French defenders of the Maginot Line and actually under French command, eventually surrendering to the Germans.

Prime Minister Churchill remained concerned with the large number of French troops still in the vicinity of Dunkirk, and as the last BEF soldiers stepped onto boats, the Germans had closed to within three kilometers of the harbor. On the evening of June 3, the resolute Royal Navy returned to Dunkirk, taking another 26,746 soldiers out of harm’s way. Still, thousands of French soldiers remained ashore.

Around 10:15 that evening, the destroyer HMS Whitsed led the final evacuation foray to Dunkirk. The effort concluded in the early morning hours of June 4, and another 26,175 soldiers, most of them French, were rescued. Operation Dynamo was officially concluded at 2:23 p.m.

Shortly after 10 a.m. on June 4, German troops began filtering into Dunkirk, rounding up approximately 40,000 surrendering French soldiers. The bodies of the dead lay everywhere. British casualties alone included 68,111 killed, wounded, or captured. The wreckage of an army, more than 2,000 artillery pieces and 60,000 vehicles, lay abandoned. At least 240 ships had been sunk, including six Royal Navy and three French destroyers.

Hitler’s order of the day for June 5, 1940, crowed, “Soldiers of the West Front! Dunkirk has fallen … with it has ended the greatest battle in world history. Soldiers! My confidence in you knows no bounds ….”

However, 338,226 British and French soldiers had escaped the clutches of the Nazis. Many of the French troops were repatriated within days and took part in the final battles before the capitulation of their country. With the long shadow of defeat hanging over it, Operation Dynamo was nevertheless labeled a triumph.

Although quietly exultant with the spectacular achievement, Churchill rose in the House of Commons on June 4 and spoke frankly, delivering one of the most stirring speeches in British history. He reminded the gathering that the German Army had swept across France and Belgium “like a sharp scythe …” and admonished, “We must be very careful not to assign to this deliverance the attributes of a victory. Wars are not won by evacuations ….”

The prime minister added with steely resolve that the prospect of a German invasion was real, but it would be resisted through to ultimate victory. “We shall go on to the end,” he intoned. “We shall fight in France, we shall fight on the seas and oceans, we shall fight with growing confidence and growing strength in the air, we shall defend our island, whatever the cost may be. We shall fight on the beaches, we shall fight on the landing grounds, we shall fight in the fields and in the streets, we shall fight in the hills; we shall never surrender.”

The road to victory in World War II, achieved five long years later, was arduous indeed, but it may be concluded that it began at Dunkirk in “glorious defeat.”

Michael E. Haskew is the editor of WWII History magazine. He is also the author of many books and articles on various historical topics. He resides in Chattanooga, Tennessee.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments