By Bernd Horn

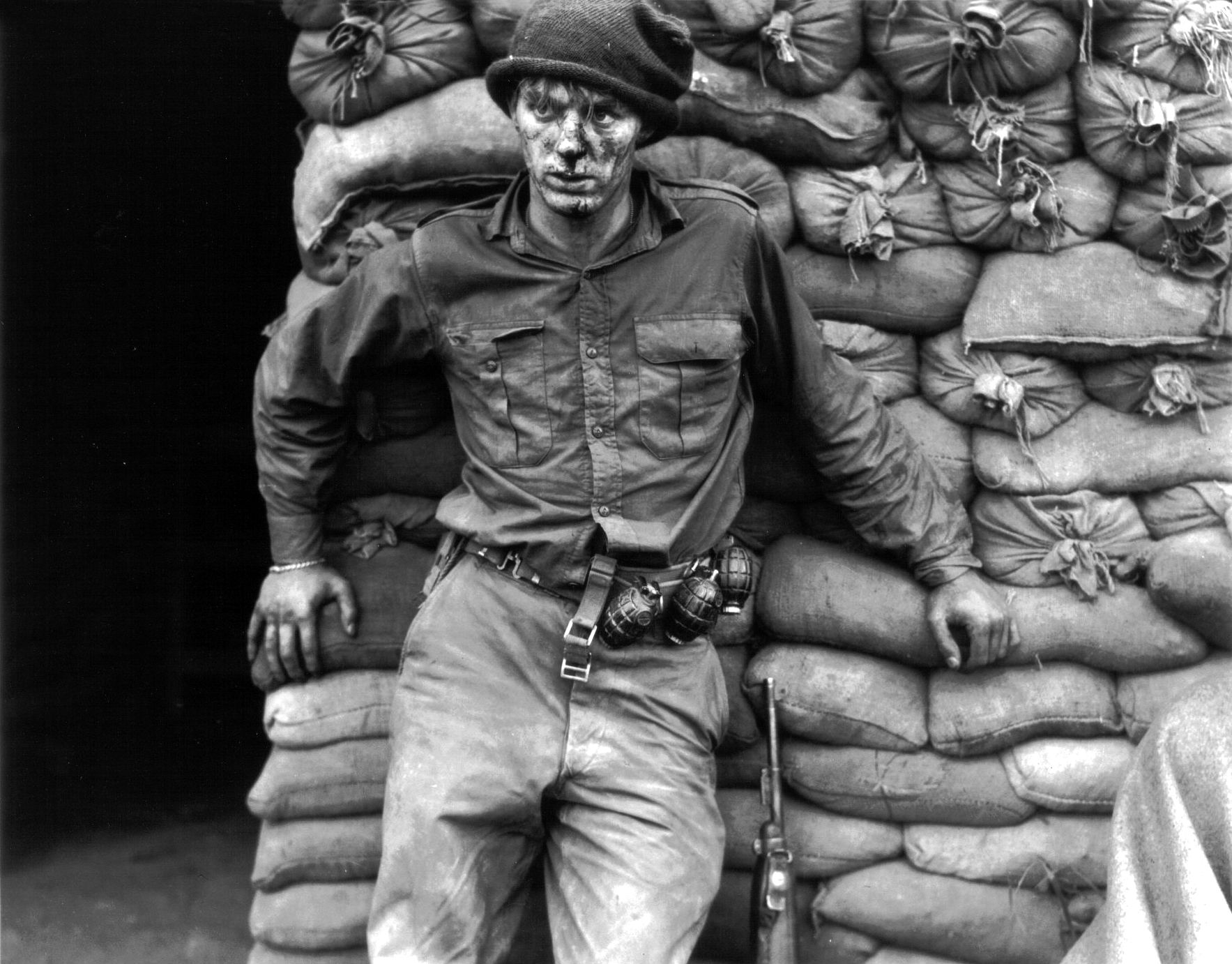

The ground heaved and trembled under the ferocious climax of the Chinese bombardment that shook the Canadian soldiers from their bunkers and weapon pits. Concussed and fighting for oxygen in the thick dust and smoke, they strained their eyes for any movement of the enemy they knew was coming. Already they could hear the whistles, trumpets and orders, as well as the hollow booms of Bangalore torpedoes as the Chinese infantry breached the wire. Private Charlie Morrison gripped his Bren gun and braced himself. Finally, he could lash back at his antagonists who had been tormenting him and his comrades for almost a month. He saw nothing in the shroud of smoke and debris. And then, the Chinese infantry was upon them with burp guns and grenades. Charlie hammered away with his Bren gun, changing magazines as quickly as he could while avoiding the overheating barrel.

The Korean War was already into its second year of bitter, sometimes savage, fighting. For the 1st Battalion, The Royal Canadian Regiment (1 RCR), the war had started about five months before when it replaced its sister battalion, 2 RCR. After only nine days in Korea and two in the line, 1 RCR found itself manning the front lines and dispatching patrols into no-man’s-land. Out of necessity, the Battalion quickly focused on learning the ropes. The patrol schedules for the first few weeks ensured everyone was able to gain confidence and experience in operating in the new combat environment. By late May, activity on both sides increased dramatically. Each night the Battalion had approximately 40-60 all ranks engaged in a myriad of standing, fighting and reconnaissance (recce) patrols. The “Royals” also introduced the “jitters” patrol—using bugles, whistles, tin-cans and any other noise making instrument—to keep the enemy in a state of anxiety.

Patrols ranged from 20 men to entire companies, with heavy supporting fire from tanks and artillery. Working their way through existing gaps in their own wire and defensive minefields the patrols crossed the floor of the valley and worked their way to the hills opposite them.

The war had in many ways evolved into a war of patrols, with deadly raids and attacks designed more to inflict casualties and dominate ground than to actually seize and hold terrain. The conflict teetered between overwhelming boredom and sheer terror. Tensions increased along the front lines during the fall of 1952 as the Royals continued with their active patrolling and the constant struggle to dominate no-man’s land.

On the night of September 24, one particular daring snatch patrol was conducted to obtain a prisoner and deliver the enemy a psychological blow. Lt. H.R. Gardner and Corp. K.E. Fowler, infiltrated deep into a Chinese defensive position to their field kitchen area behind Hill 227 where they cut a signal wire and waited for an unsuspecting Chinese technician to come repair the line. They did not have long to wait. As the unsuspecting Pvt. Wang Teh Shen began to fix the break, Gardner struck him with a blackjack while Fowler attempted to pin his arms. A furious struggle commenced with Shen shouting for help. After several minutes Shen submitted after he was threatened with a gun. However, just as the prisoner was being lifted to his feet, the first of the armed enemy response arrived. A hot pursuit was now undertaken as the Royals withdrew with their prisoner.

Fortunately, Gardner had planned well, and a series of firm bases through which he could pass assisted his party, with prisoner in tow, in breaking clean of the enemy pursuit. The 1 RCR War Diary graphically captured the safe arrival of the group: “the snatch patrol came in about 0730 hours complete with a Chink prisoner—Cpl. Fowler brought him in by the scruff of the neck.” The daring nature and success of the patrol was seen as “a feather in the cap of the Regiment.”

The daring feat, however, came at a price. The Regiment would pay dearly for their prisoner. Within a week, the Royals noted that “the front is continually being probed by small numbers of enemy with no damage being done.” At the time not much was thought of the activity. But, as events began to unravel, the Royals were struck with a chilling sense of foreboding. By end March 1952, 1 Commonwealth Division intelligence staff had developed a fairly comprehensive picture of Chinese tactics. Large scale attacks and battalion-sized raids were generally preceded by a series of nightly probing attacks that increased in size each night.

In addition, the actual attack was always preceded by artillery fire. The bombardments generally started hours prior to the actual assault working up to the most intense fire at H-Hour—the Chinese Army was known to attack through their own supporting fire. Large scale attacks were always accompanied by at least a battalion-size diversionary attack to a flank. Often tanks and self-propelled guns were used to support the attack by providing direct fire on bunkers and entrenchments. Directional tracer, flares, bugles, and whistles were all methods used to control and guide attacking enemy elements.

A Chinese attack on a given objective was always made by a direct assault on the feature itself, with an effort at a simultaneous envelopment from two sides. The enemy was adept at leaving troops to contain and attack defended localities while passing through other troops between these strong points to attack positions in depth such as command posts and gun areas. The assaulting troops were invariably armed only with sub-machine guns and grenades. Bangalore torpedoes and home-made devices were normally utilized by assaulting elements to remove defensive wire which was not destroyed by the artillery bombardment. In addition, the Chinese had stopped using mass attacks on a large front because of initial failures. They now concentrated on obtaining complete superiority at a given point, allowing them to concentrate their support weapons at the focal point of the attack.

The Royals would soon experience this first hand as, unbeknownst to 1 RCR, a tempest had been brewing. Nonetheless, activity in the line continued. The War Diary captured the harsh reality:

“Patrol activity continued…6 Royals had accomplished what the remainder of the Div[ision] had been trying to do in capturing a prisoner. All ranks are very proud of Lt. Gardner and his gallant men. Other patrols were of a less spectacular nature. There were short, sharp, bitter clashes by night where the courage and common sense of the patrol members triumphed over the enemy and the darkness. Each day …has been a testing of one or several members of this Battalion. Tests have been met.”

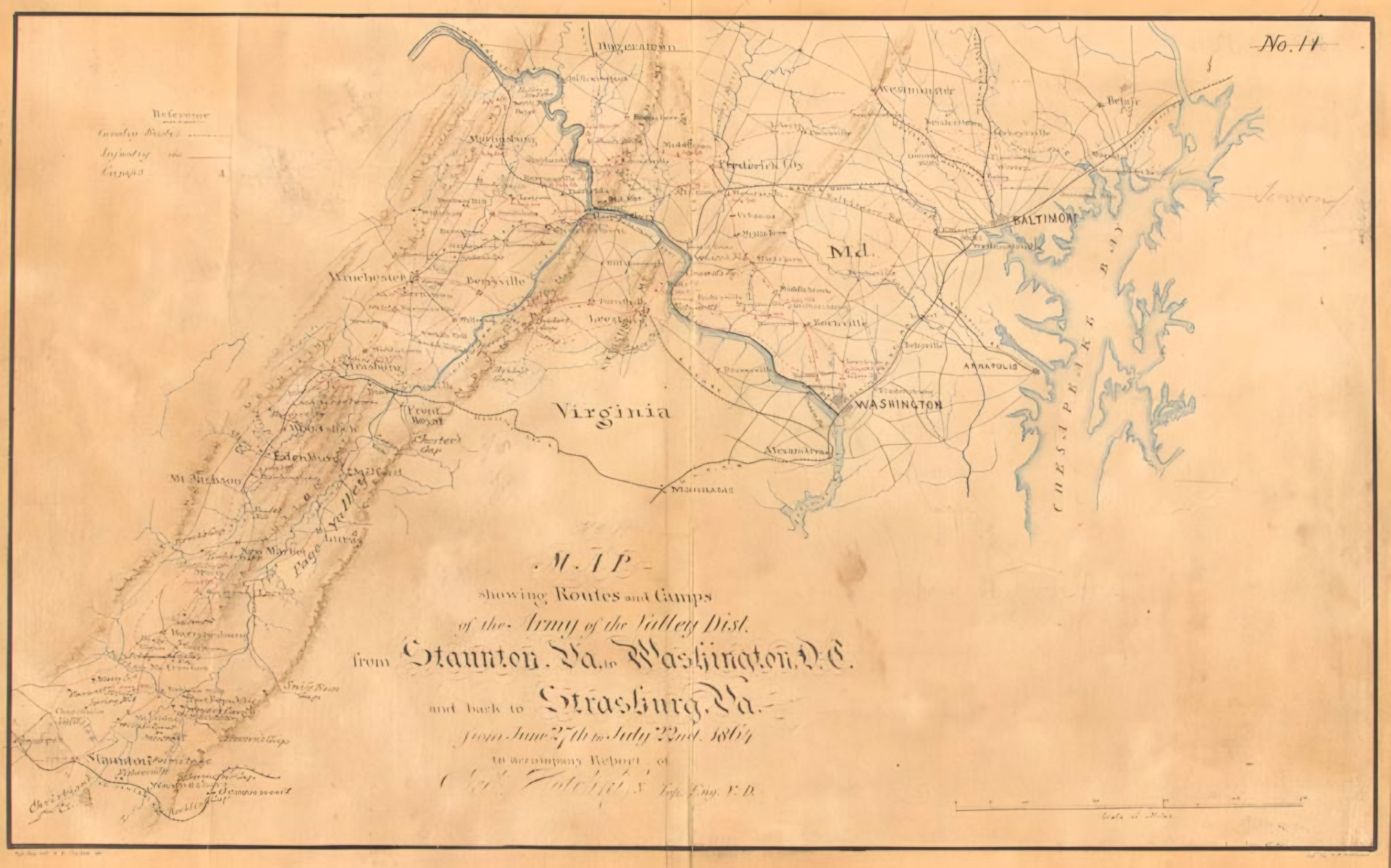

And so, 1 RCR continued its vigilance on Hill 355, labeled “Little Gibraltar” by the Americans because from the rear it bore a striking resemblance to the actual feature in the Mediterranean Sea. To the north and west, however, its features were more gradual. It was the highest feature of the surrounding area. Five company positions secured Hill 355, also known as Kowang-San on Korean maps. Area I, which was on the southeast portion of the position, was garrisoned by E Company (abbreviated as “Coy”) and faced the enemy positions on Hill 227. Area II was secured by D Coy. This critical piece of ground lay on the immediate opposite side of the saddle that ran between Hill 227 and Hill 355. In many ways, it was the doorway to Little Gibralter. Areas III and IV, manned by A and C Coy, respectively, anchored the northern front of Hill 355, and Area V, was a reserve position manned by B Coy. The Battalion felt secure on Kowang-San. In fact, one Royal wrote, “D Coy is settled in and ready for whatever happens. We on 355 feel secure in the knowledge that no Chinks can sneak up on us.”

October literally began with a bang as the Chinese, in keeping with their typical offensive doctrine, began a systematic hammering of Hill 355. On October 1, 1952, they fired nearly 1,000 rounds, primarily into Area II. The next day, the enemy dropped in another 600 rounds and succeeded in destroying the defenses in the Vancouver Outpost, which was subsequently abandoned, as well as knocking out the tank in the southern platoon area. A similar intense bombardment occurred on the third day, after which firing slackened somewhat until October 17, when the intensity of fire picked up once again. On August 21, 1,600 rounds thundered into 1 RCR. The next day, “1 RCR received 2,426 rounds from the ‘friendly’ Chinamen…18 tons of assorted misery,” according to the War Diary. In the interim, B Coy relieved D Coy in Area II, the hardest hit, after last light on October 22.

The effect of the prolonged bombardment was clearly evident. Maj. Bob Richards, the officer commanding (OC) D Coy, spent 21 days under shell fire in crowded dug-outs. “It’s bunkeritis, that’s what gets you,” Richards observed. “It’s knowing that you can’t walk around or you’ll get hit. It gets so that even when there’s almost no shelling at all you still get nervous.” He added, “and, when they pour in 1,275 a day you’ve got a problem.”

Richards acknowledged that a few men might break and then there is a risk of the feeling spreading. He proudly noted, “They all were getting a bit starey-eyed toward the end, but they all came out with their weapons.” Lt. M.F. Goldie added, “Life there is very primitive indeed. You can’t move an eyebrow without being hit. You just lie all day with your face in the dirt.”

For others, it was more literal. Privates Wilfred Main and Wilfred Mangeon were buried. They managed to make air holes to prevent smothering and then dug themselves out with their bare hands. Main lost his boots and manned an observation post for 48 hours in his stocking feet.

That the number of casualties wasn’t higher was down to discipline, according to Major Richards. “The only casualties were from direct hits on bunkers and trenches and you can’t control that. But reactions got slower all the time. At the beginning you’d give an order and they’d jump to it. Later they got to looking for shelter on the way. They’d get there all right, but it would take longer.”

When B Coy arrived into the position they found the field defenses very badly damaged and the greater part of the reserve ammunition, which was stored in the weapons pits, had been buried. In addition, the bunkers were caved in and the telephone lines cut. The fire continued throughout the day on the 23rd and into the night. B Coy stayed on alert after dark. Throughout, they could hear the detonation of heavy explosions, distinctly different from the incoming artillery and mortar shells. The soldiers knew the Chinese were blowing gaps in the wire, but the intensity of the fire prevented them from providing any form of response.

Throughout the day the bombardment had continued to wreak havoc on the company position. Bunkers, command posts and trenches collapsed. Ominously, during the day the enemy moved several self-propelled guns and infantry guns forward. Around 1700 hours, the scale of the destruction led Lieutenant Gardner and Sgt. G.E.P. Enright to attempt to reorganize the men in their platoons, which now represented a collective strength of approximately 30 men.

At 1730 hours the firing almost completely ceased. “The silence was eerie,” recalled Lt. Scotty Martin, “and somewhat unsettling after so many days of harassment.” The reprieve was not to last long. Approximately 45 minutes later the enemy hurled its most intense concentration of shells to date, focusing particularly at the left most platoon of B Coy and the right most platoon of E Coy. The Chinese had chosen the seam between the two sub-units for their break-in. As the bombardment reached its climax, the Chinese poured in shells and mortar rounds at a rate of 6,000 shells an hour for 30 minutes. This deluge of fire effectively destroyed any remaining field defenses. “At 1815 hours,” Martin recalled, “Baker and Easy companies disappeared in clouds of smoke and dust.” Pvt. Ted Zuber, who would go on to become a famous war artist, remembered, “the smoke was so thick you couldn’t see anything, it burnt your lungs.” Lt. D.G. Loomis later wrote:

“Its effect can hardly be described. It was shattering. I stopped counting the rounds about halfway through this bombardment—at 700— and I only counted the orange flashes which I could see. Before it was over visibility was less than an arm’s length due to the heavy pall of black fumes which caused everyone’s eyes to water.”

The fire then lifted and shifted to the positions adjacent to B Coy. The sub-unit was now effectively cut off from the other positions as the enemy fire pummeled A and E Coys on the flanks for 45 minutes. The Chinese then launched an attack to take the 1,500-foot peak.

As the bombardment continued on the flanks, an enemy battalion swarmed over B Coy’s shattered position. “At 1815 hrs,” the War Diary revealed, “the tense words came to the CO, ‘B’ Coy was being overrun.” It noted, “Heavy mortaring and shelling was followed by the enemy charging into ‘B’ Coy position in the gathering dusk.”

Pvt. Arthur Alexander remembered, “The Chinese came in almost on top of the barrage screaming and firing their burp guns and throwing grenades.” The OC and his headquarters (HQ), reported, “the sound of ‘burp-guns’, horns, bugles and whistles were heard even before the bombardment lifted.” Lieutenant Martin recalled, “Loud Chinese voices, whistles and bugles could be heard in Baker Company position only 50 yards away.”

Clearly, the Chinese attack was not unexpected. As a result, a defensive fire plan had been organized and was now executed. Artillery and 4.2-inch mortars thundered in assistance and hammered likely form-up points (FUPs) and approach routes. In addition, all possible Battalion heavy and medium machine-guns, as well as 81mm and 60mm mortars were called in for defensive fire (DF) tasks. As a result, a curtain of fire now rained down in front of B Coy and on to the approaches to the North of Hill 355. The A Coy War Diary recorded, “The enemy attacked ‘B’ Coy in estimated 2 Bn [battalion] strength, quickly overran ‘B’ Coy position and part of left-hand Platoon ‘A’ Coy before being brought to a standstill.”

The battle for Area II had dissolved into desperate, savage hand-to-hand combat. During the barrage Pvt. Johnny Johnston crawled from foxhole to foxhole to repair weapons. He cleaned each part with gasoline and ensured they were ready when called upon. Later he calmly stripped two jammed Bren guns in the heat of the action and put them back in service. “He’s the calmest man I’ve ever seen,” praised his platoon commander, Lt. Edward Mastronardi after the battle.

But he was not alone. Private Morrison was rooted in his fighting trench when the Chinese hordes swarmed the position. He remained in place and fought desperately to enable his comrades to withdraw. “When last seen he was engaged in close combat with enemy.”

Sergeant Gerald Enright of 5 Platoon also displayed selflessness and courage. Ordered by his platoon commander to report their situation after all radio communications broke down, Enright fought his way through to A Coy’s position under heavy fire. He reported the desperate plight of B Coy and then grabbed a radio and as much ammunition as he could carry and made his way back into the anvil of fire to assist his comrades beat back the seemingly endless tide of Chinese attackers.

Similarly, Lieutenant John Clark set a stirring example as he tenaciously held his position through the thick of the fighting. “He personally took an active part in the close fighting, throwing grenades and manning in turn a rifle, Bren and Sten until each weapon’s ammunition was expended.” When he realized that the remaining options were either annihilation or surrender, he reorganized the remainder of his platoon and successfully withdrew, carrying one of his wounded soldiers on his back, from their position to A Coy’s entrenchments to continue on the fight.

B Coy by now was completely cut-off. Its neighboring sub-unit, E Coy was the source of information for the Battalion HQ. Lt.-Col.Peter R. Bingham was on leave, so the fight was now in the hands of the acting CO, Maj. Francis Klenavic.

Observation was obscured by the smoke and dust of the raging fire-fight. The first clear information occurred at 1836 hours, when the 4 Platoon Commander arrived at Battalion HQ and reported that his platoon had been over-run. At this time, it was impossible to contact the left most platoon of A Coy and it was presumed that they had also been overwhelmed. D Coy, in the unit’s depth position, was warned off at 1850 hours to put in a counter-attack at 1900 hours. At 1910 hours, OC A Coy called in a close-in DF. To this point the extent of the enemy attack or penetration had not been determined. It was not until later, that it became clear the Chinese had merely conducted a diversionary attack against A Coy’s position.

At 1916 hours, OC E Coy deployed a small patrol to investigate the status of B Coy. They determined that the Chinese now possessed Area II. A and C Coys continued to report movement directly to the front of their positions and continued to call in “danger close” artillery strikes. At 1943 hours, OC B Coy reported that he, 5 Platoon Commander and 12 men had reached the left platoon of A Coy. He grimly reported that no friendly troops remained in action in the former B Coy area. As a result, Area II was now cloaked with fire.

Plans were now consolidated for the counter-attack to regain the lost position. By 2045 hours, all was set. A relieving force from A Coy took over D Coy’s position and all supporting tank and air assets were coordinated. The plan entailed a complex pincer movement with one platoon attacking from behind E Coy’s position, while another platoon (a diversion) would attack through A Coy.

As the final preparations were made for the counter-attack, Battalion HQ could still not determine the intent of the enemy. The weight of the attack, and the enemy’s continuing activity to the west and north of Hill 355 reinforced the belief that this was just Phase 1 of a larger attack. At 2110 hours, a sudden increase in enemy artillery and mortar fire on E Coy seemed to indicate an impending assault.

In response, all available artillery and mortar assets fired an impressive response. Area II and all approaches to Hill 355 were now covered in a blanket of fire. It appeared that the speed and weight of the response fire took the steam out of the enemy’s advance. Chinese supporting fire faltered, slackened and then tapered off to harassing fire for the remainder of the engagement.

By 0105 hours, October 24, D Coy was poised to launch the counter-attack. Seven minutes of artillery fire preceded the assault. Ten Platoon assaulted from the left and into the most extreme position of Area II. They encountered no opposition. At the same time 12 Platoon attacked from A Coy’s position on the right and occupied the center position in Area II. Once again, they too met no opposition. The enemy had melted away. By 0331 both assaulting platoons linked up and the situation was restored. D Coy then cleared out the rubble and made the position “fightable.” The grim task of evacuating the dead and the wounded then commenced.

In the end, the battle cost the Battalion 18 killed, 35 wounded and 14 taken prisoner. Interestingly, RCR prisoners released at the end of the war recounted that the attack on Little Gibraltar that triggered the Royal’s desperate struggle was the daring snatch patrol the month earlier. In fact, they insisted that the Chinese were looking for Lieutenant Gardiner and Corporal Fowler. Nonetheless, 1 RCR fought valiantly and inflicted a heavy price for the damage the Chinese had caused. As recorded in the War Diary, “The Regimental Banner atop 355 is shot and shelled—but it still flys.”

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments