By Eric Niderost

On Friday, July 29, 1588, a group of English gentlemen decided to play a friendly game of bowls after a hearty midday meal. They walked over to the Hoe, a grassy stretch of ground overlooking the harbor at Plymouth, one of England’s leading seaports. The men were dressed in full Elizabethan splendor, costumes that marked them as no ordinary mortals. One player was Lord Charles Howard of Effingham, first cousin to Queen Elizabeth I and Lord High Admiral of England. Howard was an efficient administrator with a genuine concern for the welfare of ordinary seamen, yet he was also a political appointee, chosen more for his rank than his nautical skills, which were largely nonexistent. Howard was fortunate, however, in having under his command some of the greatest mariners of the age. One of his playing companions that day, Sir Francis Drake, was England’s foremost privateer, a man known for his bold raids on Spanish colonies and shipping on the high seas. The stocky seaman from Devonshire had become famous—or infamous—as “El Draque,” the personification (in Spanish minds, at least) of a bloodthirsty pirate.

Howard and Drake knew that a large invasion force, called by the Spanish Grande y Felicissima Armada, had set sail some weeks before and was probably nearing the southern shore of their island nation. Tensions were growing, and preparations had been made to resist the invaders, but there was not much else the English could do until they received definite word of the Armada’s whereabouts. Word came soon enough. Captain Thomas Fleming, of the scout bark Golden Hind, arrived to report startling news. The Armada had been spotted near the Scilly Isles, not far from the southwestern tip of Cornwall. The long-awaited crisis was now at hand, but Drake reacted with his customary sangfroid. He quipped, “We have time enough to finish the game and beat the Spaniards too.” The privateer knew the waters well, and at the moment the incoming tide was at full flood. There was also a strong southwesterly wind, which meant that the English fleet was temporarily bottled up in Plymouth. There was nothing to do but wait for the ebb tide, which would arrive at about 10 pm.

The Spanish Armada

The Spanish Armada had its origins in the political and religious rivalries that threatened to tear 16th-century Europe apart. King Philip II of Spain was the most powerful ruler in Christendom, with far-flung dominions in Castile, Aragon, Sicily, Milan, Naples, the Netherlands, Dijon, and the Franche-Comte. Thanks to the epochal voyages of Columbus, Spain had gotten a head start in colonizing the New World. By the mid-16th century, gold and silver from Mexico and Peru were flooding into the Spanish treasury, making Philip rich as well as powerful. In 1580 Spain absorbed nearby Portugal, inheriting a vast commercial empire in Asia. Spanish power was at its height, and Spain was a seagoing colossus that straddled the globe.

Spain was also the leading Catholic power in a Europe still in the grip of the Protestant reformation. Mutual antipathy gave rise to bigotry, religious persecution, and sometimes open warfare. In France a Protestant minority, the Huguenots, were battling Catholics for control of the kingdom. In England the situation was different. King Henry VIII had established the Anglican Church because the pope had refused to grant him a divorce from his queen, Catherine of Aragon. The king soon married a very pregnant Anne Boleyn, but to his great disappointment Anne delivered the future Queen Elizabeth I. In Catholic eyes, Elizabeth was the “daughter of adultery,” a bastard with no real claim to the English throne.

Conflict over Commerce

Elizabeth was essentially a tolerant woman. When she came to power in 1558, she reestablished her father’s Anglican Church. It was a middle-ground, compromise church, Protestant in doctrine but with many trappings of Catholic ceremony. It was also an attempt to unite her people and end religious strife. Most Englishmen fell into line and attended Anglican services, although the Puritans—radical protestants—and a few hard-core Catholics rejected the compromise.

In the early years of Elizabeth’s reign, relations between England and Spain were cautiously cordial. The first hints of trouble between the two countries came in the 1560s. As the English economy revived, the nation developed a new interest in overseas trade and commerce. John Hawkins, a Devonshire trader, felt that Spain’s New World colonies were an untapped source of commercial wealth, but Spain discouraged foreign trade with her American possession. To all intents and purposes, it was illegal to trade with any of Spain’s colonies, and anyone caught doing so faced grave consequences. Hawkins was willing to take the risk, and in the 1560s he began a series of slave-trading voyages to America that proved exceedingly lucrative. Even the queen took her share of the profits.

Eventually, Hawkins’s luck ran out. When his storm-battered vessels limped into San Juan de Ulua, a powerful Spanish treasure fleet arrived on the scene and effectively bottled him up. After some negotiations, a gentleman’s agreement was reached that would permit the English to depart in peace. But it was really a trap that was soon sprung on the unsuspecting English. The Spanish attacked, and after heavy fighting only two English ships managed to slip the net and escape. One was commanded by Hawkins, the other by his young cousin, Francis Drake. The incident was remembered bitterly by Hawkins, Drake, and other English mariners, who swore Revenge. English privateers—the Spanish called them pirates—raided Spanish colonial ports and treasure ships on the high seas. Although England and Spain would remain officially at peace for another 30 years, the die was cast for an eventual collision between the two superpowers.

“Heretical” Queen Elizabeth’s Proxy War

Philip soon had other grievances against England’s “heretical” queen. The Netherlands had openly revolted against Spanish rule, which Philip tried to brutally suppress. The fact that most of the rebels were Protestants added to Spanish zeal and brutality. As time went on, it became clear that it was not in England’s best interest to have a powerful and potentially hostile Spanish army just across the English Channel. Elizabeth began sending Dutch rebels secret aid. The growing war between the faiths also forced Elizabeth’s hand. In 1570, Pope Pius V issued Regnans in Excelcis, a document that excommunicated Elizabeth as a heretic and usurper. Her Catholic subjects were absolved from any allegiance to her or the government. Later, the pope issued a bull that encouraged English Catholics to take up arms to overthrow the queen. This was a direct challenge, and over the years several plots to assassinate Elizabeth and replace her with her Catholic cousin, Mary, Queen of Scots, were uncovered. Mary, under house arrest in England, was finally executed in 1587 for her role in the plots.

For Philip, the execution of the Scottish queen was the last straw. He had no great love for Mary, who had had strong ties with France, but the king’s patience had run out. On the evening of March 31, 1587, Philip issued a flurry of orders from the Escorial, his gloomy palace and monastery on the sun-baked plains of Castile. Couriers sent dispatches to every corner of Spain’s extensive empire. Arsenals at Barcelona and Naples were ordered to send all available weapons to the Atlantic fleet. The royal missives were precise, omitting no detail. Ships must be added to the fleet, and existing vessels made ready for a long sea voyage.

Building up for War

Lisbon became a beehive of activity, with ships overhauled, caulked, and covered with tallow. Cargoes of hemp, sailcloth, tackle, and spars were brought down from the Baltic in preparation for the great enterprise. It had taken Philip years to make up his mind, but once the decision was made, he grew increasingly impatient. Admiral Alvaro de Bazan, Marquis de Santa Cruz, was told to have the fleet ready to set sail before the spring of 1587. The marquis was one of Spain’s greatest admirals, battle-hardened and experienced. He knew that England would be a tough nut to crack, and he wanted a force so formidable that nothing could stand against it. Santa Cruz asked for a fleet of 556 ships and an army of nearly 95,000 men. Philip’s eyes must have glazed over when he saw the estimated cost, an astronomical four million ducats, or four years’ worth of revenue from Spain’s New World colonies. Santa Cruz’s idea was rejected because of its prohibitive cost, but preparations continued for the holy crusade to defeat the heretics and reestablish the Catholic Church in England.

A Preemptive Raid at Cadiz

In the meantime, the English were watching events with growing alarm. Preparations on this scale could not be hidden, and the queen’s spymaster, Sir Francis Walsingham, had an efficient network of operatives. Ever chafing at the bit, Francis Drake proposed a preemptive strike against Spain before the Armada could sail. The queen cautiously approved; she genuinely wanted peace, but the threat was too great to ignore. Drake set sail for Cadiz, Spain’s largest port on the southeast coast, with 25 vessels. When he arrived, he found the harbor crammed with 60 ships, from the smallest caravel to a magnificently armed Genoese merchantman. He took what prizes he could and burned the rest. By his own reckoning, Drake destroyed 24 Spanish ships and took another six ships packed with supplies.

The raid at Cadiz threw Spanish plans into disorder and delayed the Armada by a full year. By some estimates, Philip sustained losses amounting to 200,000 ducats, and the Cadiz segment of the Armada was virtually destroyed. The Spanish monarch took the news calmly, more determined than ever to push forward. It was almost unnoticed at the time, but Drake had followed up his Cadiz raid with a foray to Cape St. Vincent. He sailed through the tuna-fishing grounds, sinking many of Spain’s fishing boats in the process. The Armada needed stocks of salted fish for the long voyage—now they would be in short supply. The wily Englishman also encountered merchantmen carrying barrel staves, seasoned wood ideal for water casks and other containers. These ships were sent to the bottom. In the months to come, the Armada would have to rely on barrels made of green wood, which caused water and food to spoil more rapidly.

“No Experience Either of the Sea or of War”

Philip chafed at the seemingly endless delays, bombarding Santa Cruz with a steady stream of letters urging haste. “Success depends mostly on speed,” the king wrote in a typical missive. “Be quick!” Worn out by the sheer scale of his responsibilities, Santa Cruz took ill and died unexpectedly on February 9, 1588. His death at age 62 made a questionable project even more dubious. By this time, however, Philip had convinced himself that he was God’s instrument for the punishment of an impious England. After a short deliberation, he named Don Alonzo de Guzman el Bueno, Duke of Medina-Sidonia, to replace Santa Cruz.

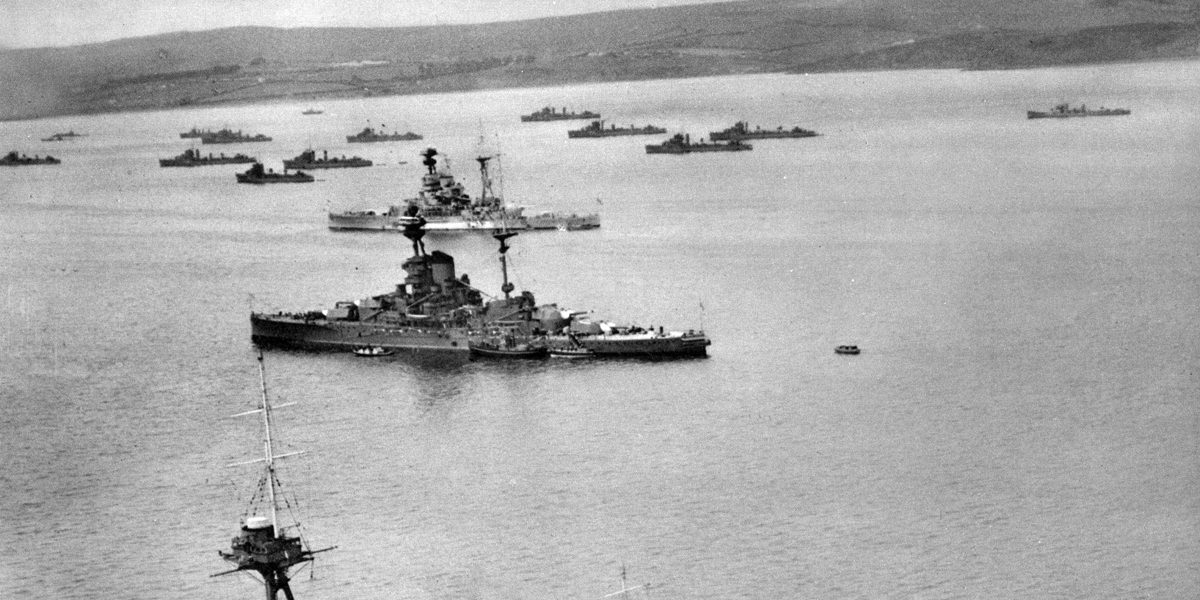

Medina-Sidonia was appalled when he heard of his appointment and did everything in his power to be excused. In one pleading missive, he wrote, “I know by experience of the little I have been at sea that I am always seasick and always catch cold.” When this pitiful ploy fell on deaf ears, the duke tried a more rational argument, stating that “since I have had no experience either of the sea or of war, I cannot feel that I ought to command so important an enterprise.” The king would not change his mind, so Medina-Sidonia manfully accepted his fate. In the spring of 1588, the Armada was at last ready to set sail. It was a powerful force of 130 vessels, made up of nearly very kind of craft imaginable. There were stately galleons, oar-driven galleys, square-rigged carracks, and big-bellied transports. The fleet was handled by 8,000 sailors and carried some 20,000 soldiers, with an impressive array of ordnance, including 2,431 guns.

Organization of the Fleet

The men needed sustenance, and Philip made sure that the Armada had enough supplies to last six months. There were 800,000 pounds of cheese, 600,000 pounds of salt pork, 11 million pounds of ship’s biscuits, and 14,000 barrels of wine crammed into cargo holds. Nothing was forgotten—there were also 11,000 extra pairs of sandals, 5,000 pairs of shoes, and thousands of spades and shovels for digging trenches in siege warfare. Since this was a holy crusade, much care was taken to provide for the expedition’s spiritual welfare. Some 180 priests and friars were also aboard to conduct religious services and possibly convert the English.

The 130 ships were divided into 10 squadrons. The first two squadrons contained the Armada’s most powerful ships, mainly galleons from Castile and Portugal. Medina-Sidonia was in this group, sailing on the Portuguese galleon San Martin with his chief of staff, Diego Flores de Valdes. There was also a Biscay squadron, a Guipuzcoa squadron, an Andalusia squadron, and a Levant squadron, mainly armed merchantmen. The Levant squadron was a hodgepodge of vessels from every part of Europe—eloquent testimony of the far-flung power and influence of Spain. There were also ships from Venice, Genoa, Naples, Barcelona in the Mediterranean, Ragusa on the Adriatic, and Hamburg on the North Sea.

Back in England, Drake and others urged the queen to launch another preemptive strike. Elizabeth was a brilliant ruler, but she could be exasperating at times, especially when she continued peace negotiations and prepared for war simultaneously. Alexander Farnese, Duke of Parma, was Philip’s governor general of the Netherlands, and he encouraged Elizabeth to think that a negotiated settlement was still possible. Whether the queen really believed Parma’s rhetoric is a moot point. Elizabeth was a master of pragmatic politics. If a negotiated peace could be accomplished, well and good. If not, she could still rely on England’s fine ships and mariners to protect her realm.

Hazards of the Voyage

The Armada finally set sail from Lisbon on May 28, with a total complement of 19,000 soldiers and 10,000 sailors. There were so many ships that it took the multitude two full days to clear the harbor. Hopes were high, but bad luck plagued the enterprise from the start. The spring was unseasonably stormy, and the ships had to plow though periods of bad weather. Progress was slow because the heavily laden supply ships moved at a snail’s pace and the fleet had to keep together. When water barrels were opened, their contents were found to be green and stinking. The food was spoiling, too, because Spanish coopers were forced to make barrels from green wood. The Armada put in at Corunna, a port on the northwest corner of Spain, for repairs and reprovisioning, before setting sail for England in early July.

For all its power and might, the Armada’s mission was essentially a passive one—namely to ferry the Duke of Parma’s 30,000-man army from Flanders to England. Without modern communications, coordinating the Armada’s movements with Parma’s army would be difficult at best. The invasion plans seemed to rely on wishful thinking that took little account of the real challenges facing the project. The Armada lacked a deepwater port to rendezvous with Parma and to serve as an embarkation point for the invasion army. Much of Flanders was problematic: its coast was filled with deadly sandbanks and treacherous shoals, its inland areas laced with a bewildering labyrinth of canals and waterways. Parma was busy building scores of flat-bottomed barges, in the hope that these vessels could reach the Armada in deep water. The English Channel and adjacent waters posed more than just natural dangers. Dutch rebels sailing in flyboats—shallow-draft, two-masted gunboats—would find the clumsy barges easy prey on the open sea.

The English Flank the Armata

When Howard learned of the Armada’s approach on July 29, he ordered the English fleet to set sail at once. This was easier said than done—a strong wind was blowing into the harbor, and the ships had to be towed by long strings of rowboats. Once out of the Plymouth harbor, the English were still at a disadvantage. The Armada plowed up the Channel at a steady pace, its progress aided by a strong south-southwest wind. The Spanish thus had the weather gauge, and with the wind at their backs they could maneuver more effectively than the English, even though the English ships were generally smaller and faster.

Conventional thinking had Howard going to the east to block the Armada’s passage up the Channel. But Howard, no doubt influenced by his vice admiral, Francis Drake, had other ideas. The English fleet would tack against the wind, skirting around the Armada in an attempt to get behind the enemy fleet. English seamanship was superb; during the night of July 30-31, Howard managed to slip past the seaward flank of the Armada, while a smaller English squadron went past its landward flank. On the morning of July 31, Spanish lookouts saw a large group of sails on the horizon—it was the English fleet, far to the Armada’s rear and enjoying the same south-southwest wind. The Spanish were both amazed and dismayed.

As the English closed, it was their turn to be amazed. The Armada was a truly awesome sight, long remembered by those Englishmen fortunate enough to have beheld its magnificence and splendor. “You could hardly see the sea,” one English sea dog recalled, “so thick was the gaudy clutter of masts, sails, banners, and battlements.” Another declared there were so many great ships “the ocean was groaning under the weight of them.” Many of the Spanish sails were emblazoned with red crosses, and a colorful array of banners, pennants, and flags waved gracefully in the wind. Each squadron had its own emblems and colors, including the red castles of Castile, the dragon and shields of Portugal, and the crosses and foxes of Biscay. The great galleons rose up from the water like wooden mountains, their high forecastles and sterns towering fortresses threatening to rain destruction down on the enemy.

The Battle Begins

Around 9 am, the two fleets were close enough to give battle. The formal opening of hostilities harked back to the age of chivalry. Howard dispatched his personal pinnace, aptly named Distain, to “show the Duke of Medina defiance.” The little vessel sailed toward San Martin, fired a solitary culverin at the Spanish flagship, then beat a hasty retreat. The gauntlet had been thrown down.

In reply, Medina-Sidonia raised a silk standard, the sacred banner of the expedition, bearing the Latin legend, “Exurge Domine et Vinica Causam Tuam,” or “Arise O Lord and Vindicate Thy Cause.” The duke ordered a cannon to be fired, a signal for the Armada to assume a defensive posture. In response, the entire Armada formed itself into a large defensive crescent, with the more vulnerable supply ships in the center and the most powerfully armed ships defending the wings. The English, witnessing the spectacle, could not help but admire the way the polyglot force—Spaniards, Portuguese, Italians, and others—got into position so quickly and efficiently.

Wasting no time, Howard bore down on the southern horn of the crescent, his flagship Ark Royal in the lead and the rest of his squadron in single-file formation. Although he didn’t know it, Howard was closing on the Spanish Levant squadron. In fact, by sheer coincidence, Howard was about to engage the 800-ton carrack Rata Santa Maria Encoronada, commanded by Don Alonzo de Lieva. De Lieva was every inch the dashing cavalier, noted for his flaxen hair and dazzling blond beard. Ark Royal and Rata Santa traded broadsides, their gunports erupting in long fingers of smoke and flame accompanied by deafening roars. The other members of the Levant squadron joined the fray, including the 1,200-ton Branzona, the Armada’s largest single vessel.

Differences in Doctrine

The differences between English and Spanish tactics and basic philosophies of war stood out in sharp relief. To the Spanish, ships were floating fortresses to be grappled and taken at sword’s point, but to the English, they were fast and maneuverable gun platforms. As much as possible, the Spanish preferred to fight sea battles the same way they fought on land—at close quarters with arquebus, pike, and sword. The English, on the other hand, had adapted new techniques, including battering an enemy into submission by long-range cannon fire. The English galleon, fast and maneuverable, allowed gunners to rake enemy ships with a hail of cannonballs from stem to stern.

The first engagement set the pattern for the coming days. Try as they might, the Spanish could not get close enough to the English to grapple and board. Hundreds of Spanish soldiers, their armored breastplates and helmets glistening in the sun, packed the decks, eager to come to grips with the enemy. Instead, they were impotent spectators of an artillery duel they could not participate in—except to fall wounded or die.

A Tactical Stalemate

While Howard battered the Levant squadron, Drake turned his attention to the Armada’s landward wing. Taking the lead in Revenge, accompanied by a number of ships that included John Hawkins in Victory and Martin Frobisher in the 1,000-ton Triumph, Drake headed straight for the Biscay squadron, which was downwind from the rest of the Armada. One large galleon stayed behind, a seemingly illogical gesture that must have puzzled Drake and his men. The ship, San Juan de Portugal, was a 1,000-ton galleon boasting 50 guns and 500 fighting men. She was the flagship of the Biscay squadron, commanded by the proud and pugnacious Don Juan Martinez de Recalde. Recalde was looking for a fight, hoping to act as bait for a larger engagement. Perhaps the English would throw caution to the winds and get close enough for his men to grapple and board in the time-honored fashion.

It was not to be. For two hours Revenge, Victory, and Triumph peppered San Juan with a barrage of cannonballs. When other Spanish ships belatedly came to the ship’s rescue, the English followed Howard’s orders and broke off their attack. At about 4 pm, Nuestra Senora del Rosario collided with another Spanish ship and lost her bowsprit, then lost her foremast in heavy weather. These twin misfortunes left the vessel dead in the water and unable to keep up with the rest of the Armada. Eventually she was captured by Drake. Worse was to follow. Salvador blew up, killing 200 men. It may have been sabotage or a tragic accident, but the ship was reduced to a wreck that had to be towed out of line.

The next three or four days were much the same as the first hours. The Armada was invincible in its crescent formation, but it could not come to grips with the English fleet. A tactical stalemate developed, and the English soon found they were running low on ammunition. Eventually, Howard decided to split the English fleet into four squadrons. He would take one unit, but the others would be commanded by the three finest captains of the age: Drake, Hawkins, and Frobisher.

English Fireships Breed Confusion

The Armada headed for Calais—still not a deepwater harbor, but for Medina-Sidonia and his weary sailors literally and figuratively a port in a storm. Calais was a French town, and although most Frenchmen had little love for Spain, the English feared they might cooperate with the Armada. Drake and the others worried that the French might permit the Duke of Parma to use Calais as an embarkation port. The Armada had to be sent packing, and the sooner the better. On Sunday, August 7, Howard held a council of war in his cabin aboard Ark Royal. After some deliberation it was decided to send fireships to scatter and confuse the enemy. A total of eight English ships were donated for the scheme, including one of Drake’s vessels, Thomas. The ships were stuffed with tarred fagots, and their guns were double-loaded to add to the overall terror and confusion. Once the guns grew red-hot in the spreading conflagrations, they would explode.

The Spanish were expecting a fireship attack and had posted pinnaces to give early warning and fend them off. Sure enough, flickers of light appeared on the horizon, orange-yellow dots that pulsated in the inky darkness. As they drew nearer, every detail of the burning vessels could be seen in horrifying detail. Each ship was a funeral pyre, her masts and spars consumed by greedy tongues of flame that shot high into the sky and showered the dappled waters with cascades of sparks. The Spanish pinnaces managed to grapple and tow away two fireships. The others drifted into the Armada, where they caused confusion and panic far greater than the English had anticipated. The panic spread when the fireships began to explode. No Armada vessel was set afire, but most ships still cut their anchor cables and fled pell-mell into the night.

Howard Takes the San Lorenzo

The early morning of Monday, August 8, showed the Armada ships in complete disarray. The galleass San Lorenzo had collided with another ship the previous night and had sustained serious damage. With her rudder smashed and her mainmast cracked and threatening to topple, the wounded vessel made a desperate bid to escape the English. The galleass was a hybrid, both sailing ship and oared galley, and her sweating slaves pulled at the oars and flailed at the waters with a steady beat. San Lorenzo slammed into a hidden shoal and stuck fast.

Since the shoals were too dangerous for his own galleons, Howard lowered soldier-filled boats to claim the prize. San Lorenzo offered fierce resistance, fighting furiously as the English clambered over the sides in an attempt to board. Spanish arquebus fire was heavy, until English boats were filled with dead and wounded. Then the English had a stroke of luck. San Lorenzo’s commander, Don Hugo de Moncada, was killed when a musket ball smashed into his skull. Spanish resistance collapsed with his demise. English sailors began to gleefully loot the ship, which was stuck fast on the sand bank.

Sir Francis Drake and the Battle of Gravelines

While Howard was busy trying to capture San Lorenzo, Drake and some of the other sailors were after the handful of Spanish ships that faithfully remained with Medina-Sidonia’s flagship, San Martin. Medina-Sidonia had only six galleons at first, but as time went on more Spanish ships belatedly arrived on the scene. There were perhaps 25 Spanish ships in all, most of them well armed and ready to give a good account of themselves. The resulting engagement, known to history as the Battle of Gravelines, was the climax of the Armada campaign. The English, encouraged by their successes thus far, closed with their prey and unleashed broadside after broadside into the towering Spanish galleons. Drake led the way in Revenge, followed by the rest of his squadron.

English cannonballs punched holes into San Martin’s sides, smashed guns off their mountings, and splintered her upper works. Still the galleon fought on. Frobisher’s squadron followed Drake’s, circling the Spanish flagship like a pack of wolves around a wounded stag. Other Spanish ships also came in for a share of punishment. One unnamed carrack heeled over before the wind, blood pouring from her scuppers. Cannonballs took off arms and legs with horrifying ease and smashed through bulkheads, sending lethal showers of wooden splinters whizzing through the air.

Tactical Draw, English Strategic Victory

Heavy seas and a sudden squall finally broke off the action after several hours. Two Spanish ships, San Felipe and San Mateo, were run aground to prevent them from sinking, but after a soaking rain the Armada was able to reform its defensive crescent. Bloody but unbowed, the Spanish were ready to renew the fight, but the English declined. Most of the English vessels had simply run out of ammunition. What was left of the Armada headed north, hoping to reach Spain by circling the British Isles. All hope of affecting a rendezvous with Parma was gone, replaced by a grim determination to survive.

Not knowing that the Armada was in effect defeated, Queen Elizabeth went to Tilbury, about 20 miles from London, to join troops gathering to defend the Thames River basin. Elizabeth showed her customary defiance, exclaiming, “I know I have the body of a weak and feeble woman, but I have the heart and stomach of a king, and a king of England, too.”

The Armada was in bad shape, with many vessels resembling sieves. Some were held together by cables, while others had pumps working day and night to prevent them from sinking. Storms assaulted them, causing about two dozen ships to be wrecked along the Irish coast. By some miracle, 67 ships and about 10,000 men eventually reached Spain, but many of the survivors died later of disease. Medina-Sidonia was among the survivors. Philip did not punish the nobleman, who returned to his orange groves a chastened man. The Spanish king took the news of the disaster with his customary stoicism. “I sent my ships to fight against the English,” he commented drily, “not the elements.”

In military terms, the Armada campaign was a tactical draw. The English fleet was relatively unscathed, but some 4,000 or more sailors subsequently died of typhus and dysentery. Spain remained a great power for decades to come, her coffers replenished by a steady stream of New World silver and gold bullion. But in political and psychological terms, the Armada campaign was a great English Victory. Protestant Europe rejoiced, and the Elizabethan Age, the age of Shakespeare, was allowed to flourish without fear of foreign rule or the unspeakable terrors of the Spanish Inquisition.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments