By Roy Morris Jr.

The cold North Sea surf washed over the boots of the advancing English infantry of Oliver Cromwell’s New Model Army as they tromped through the drifting sand dunes across the beach at Dunkirk on the morning of June 14, 1658. Ahead of them lay the main Spanish position, a 150-foot-high hillock commanding the enemy’s right flank. It was about 10 am, and the tide was going out.

No order had been given for the English to advance, but the rumored presence of Royalist troops under James Stuart, brother of pretender to the throne Charles II, spurred on the veterans of England’s recently concluded civil war. The merest glint of a nobleman’s jewels was reason enough for the proud Protestant commoners to attack. They had crossed the sea to the Spanish Netherlands a few weeks earlier to continue fighting Catholic monarchs, in this case Spanish King Philip IV, who had entered into an unholy alliance with Charles II to restore the English royal to the very throne that Cromwell and his Roundheads had emptied of Charles’s father, Charles I, a decade earlier. It did not matter to them that they were serving a second, at least nominally Catholic monarch, French King Louis XIV. Their quarrel was with the Stuarts—and the Stuarts’ was with them.

The Politics of Civil War

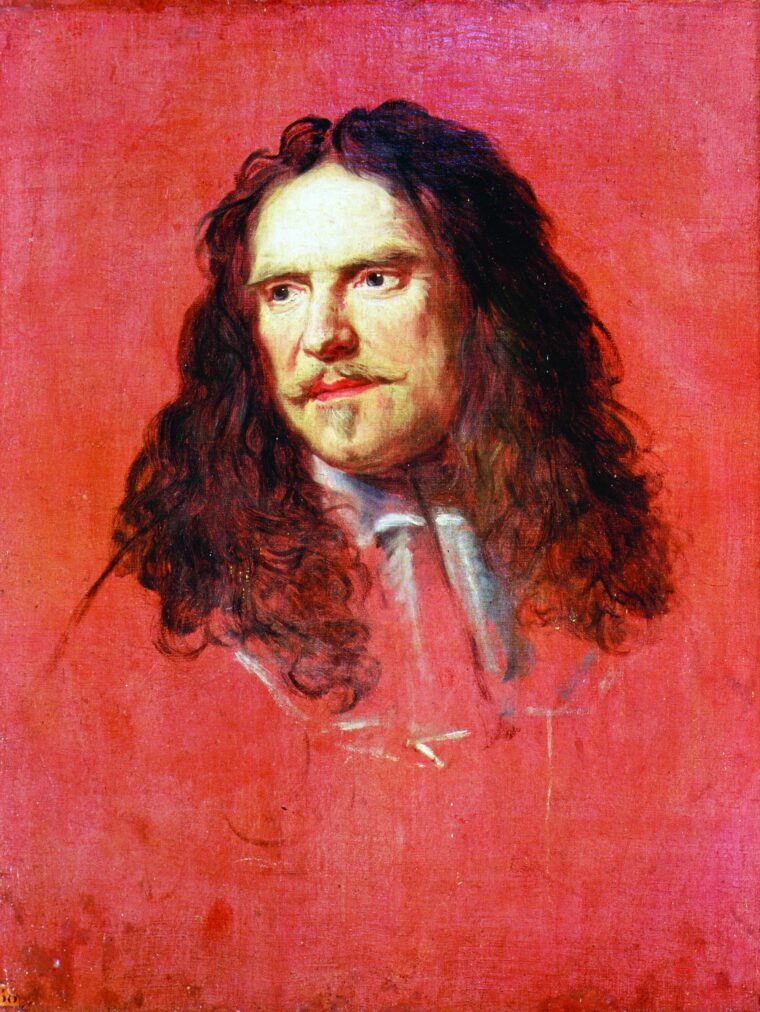

A Flemish beach was an odd place for the last pitched battle of the English Civil War to take place, but no odder than the ever-shifting marriages of convenience among the various English and European factions there that day. To begin with, the contending armies were each commanded by a Frenchman, former comrades-in-arms who already had taken a bewildering variety of positions in their country’s endless round of civic disturbances, known collectively as La Fronde. Louis’s army was led by Henri de la Tour d’Auvergne, the Vicomte de Turenne, a Protestant nobleman who once had fought against the king in the first War of the Fronde (so named for the child’s slingshot, or fronde, which had been used by rebel mobs to break out the windows of royals during the initial outbreak of unrest in Paris in 1648). Turenne had been suspended briefly for his part in the revolt, which was less a spontaneous revolution of the people than an assertion of rights by highly born noblemen, but he soon repented his actions and was restored to command of the king’s forces during the Second War of the Fronde in 1651.

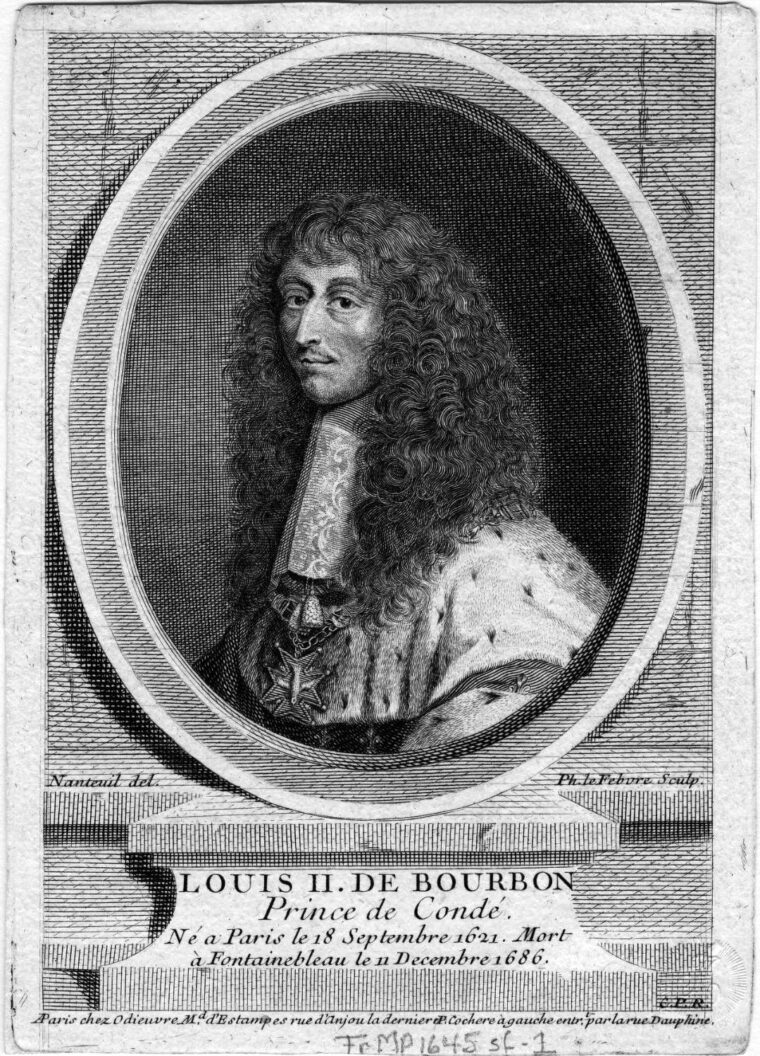

Opposing Turenne was Louis II de Bourbon, the Prince of Condé, a cousin of the king who had served with Turenne during the just-concluded Thirty Years’ War. The Great Condé, as he was called, had remained loyal during the First Fronde, but had become disgruntled at the king’s seemingly insufficient gratitude and had switched sides during the second uprising. Arrested and thrown into prison, Condé was released by Queen Anne, the 13-year-old king’s mother, who was serving as regent until her son reached maturity. Condé, showing a fair amount of ingratitude himself, immediately declared war on the royal family and defeated a loyalist force at Bleneau. (“It’s too bad decent people like us are cutting our throats for a scoundrel,” he told his defeated counterpart.)

Emboldened by his success, Condé marched on Paris, which had declared itself neutral in the second Fronde, but Turenne’s larger army penned Condé literally against the gates of the city during the Battle of Faubourg Saint-Antoine, on July 2, 1652. At literally the last minute, Condé was saved by the actions of a quick-thinking frondeuse named Anne Marie Louise d’Orleans, the fabulously wealthy Duchesse de Montpensier, who opened the gates for Condé and his men and provided covering fire from the walls of the Bastille. The duchesse, a cousin both of Louis XIV and Charles II (who had courted her ineffectually as a teenager), paid for her intervention soon enough. After Louis XIV returned to the city later that summer, he banished her from his court for the next five years.

Fleeing Paris, Condé took his battered army northward into the Spanish Netherlands (present-day Belgium) and offered his sword to Spanish King Philip IV, who had been carrying on his own desultory war against France for nearly two decades. Philip was glad to have the services of an experienced general such as Condé, and he immediately gave him command of his main army in the field. The Third Fronde, also called the Spanish Fronde, began in 1653. For the next four years, Condé and Turenne sparred indecisively along the largely denuded border between northern France and the Spanish Netherlands. First Turenne, then Condé won battles at Arras and Valenciennes, respectively. The war settled into a dull stalemate.

Meanwhile, Cardinal Jules Mazarin, the chief adviser to Louis XIV and his mother at court, worked to cement a surprising new alliance with Spain’s other major enemy of the time, England. The English Protestants, under Oliver Cromwell, recently had thrown off the shackles of hereditary monarchy and chopped off Charles I’s head for good measure. But the pretender to that perilous throne, the late king’s son, Charles Stuart, had escaped to the Continent, where he met incognito with representatives of his fellow monarch, Philip IV, and urged him to invade England and restore Charles to the throne. In return, Charles promised to return to Spain the rich Caribbean island of Jamaica, which Cromwell’s far-ranging navy had seized in 1655 during the clumsily prosecuted campaign known as the Western Design. Charles pledged to prevent further English encroachment into the New World and to secretly recognize the rights of Catholics at home. He would also provide, in time, some 2,000 English troops under the command of his brother James, the Duke of York, to Philip’s force.

To Divide Flanders

Cromwell’s spies had been monitoring the Pretender’s one-man diplomatic efforts from the start. Cromwell, for his part, was not too alarmed. Charles, he said, “is so damnably debauched he would undo us all. Give him a shoulder of mutton and a whore, that’s all he cares for.” Still, he decided to see Charles’s gamble and raise him a stake. Operating under the time-tested philosophy that “the enemy of my enemy is my friend,” Cromwell opened negotiations with the flamboyant Mazarin, who was renowned both for the sumptuousness of his dress and for the perfumed pet monkey that he kept habitually at his side. In truth, Cromwell cared little more for French Catholics than he did for the English monarchy—or pet monkeys, for that matter—but he was nothing if not practical when it came to power politics.

To curry Cromwell’s favor, Mazarin expelled Charles and his entourage from Paris. (“You will do well to put him in mind that I am not yet so low, but that I may return both the courtesies and the injuries I have received,” a humiliated Charles said upon leaving.) Now, in the name of Louis XIV, he agreed to mount a joint Anglo-French expedition against Spanish forces in the long-disputed region of Flanders. France would provide an army of 20,000 men, while England would contribute 6,000 foot soldiers and the power of the English fleet to blockade and capture the coastal fortresses of Dunkirk, Mardyke, and Gravelines. Afterward, they would divvy up the spoils between them, with England taking title to the first two towns and France assuming control of the third. As a sop to the Catholic cardinal, Cromwell personally guaranteed freedom of worship for the presumably godless papists in Dunkirk and Mardyke. The agreement would be in effect for one year only.

Announcing his treaty with the Catholic French, Cromwell gave several reasons for his remarkable turnaround. The fundamental part of the treaty, he said, was a secret clause in which both parties swore not to shelter or assist “the internal enemies” of the other. It was not entirely clear who such enemies were, at least from Louis XIV’s point of view, in Protestant-controlled England—most of his enemies were already openly arrayed against him in northern France and the Spanish Netherlands. As for Cromwell, there undoubtedly were Royalists still operating underground in England, but the Pretender and his brother were safely, if annoyingly, away on the Continent, and they were by definition an external threat to his government. So, for that matter, was Spain, which Cromwell defined as “papal and Anti-christian” and castigated for having “espoused Charles Stuart.” That was grounds enough for another war.

Cromwell further justified the war with Spain—or had it justified for him—by depicting England as a righteous avenger of the countless thousands of New World Indians who regularly had been victimized, colonized, and brutalized by the Spanish for the better part of two centuries. This point was driven home forcefully in a pamphlet written by Puritan poet John Milton’s nephew John Philips, who diplomatically dedicated the screed to Cromwell. Entitled The Tears of the Indians: Being an Historical and True Account of the Cruel Massacres and Slaughters of Above Twenty Millions of Innocent People, Philips’s work laboriously detailed Spanish abuses from the conquistadors to the present. It was extremely unlikely that any of their victims would ever hear of their far-distant vindication in Western Europe, but it gave Cromwell another arrow, so to speak, in his quiver of righteousness. He bluntly warned Parliament, “Why, truly, your great enemy is the Spaniard. He is a natural enemy, by reason of that enmity that is in him against whatever is of God. He hath an interest in your bowels.”

A Slow Invasion of Flanders

Whatever its justifications, the new alliance got off to a slow start. In May 1657, Turenne assumed command of the invasion force; Sir John Reynolds led the English contingent. Crossing the border into Picardy, Turenne began a diversionary movement on the inland stronghold of Cambrai. His old chess partner, Condé, immediately moved against him. Of the two, Turenne was characteristically the more cautious campaigner. He quickly pulled back from Cambrai and consolidated his force with the newly arrived English troops at St. Quentin. The six English regiments were all Protestant, many of them veterans of their country’s civil war. Under the terms of the Anglo-French treaty, Scots and Irishmen were precluded from serving on the expedition since they could not be trusted to bear arms against their coreligionists of the House of Stuart. For the first time outside of England, the soldiers wore the bright-red coats of Cromwell’s New Model Army and followed the muscular philosophy of Puritan theologian Samuel Rutherford, who maintained, “The thing which we mistake is the want of victory. The want of fighting were a mark of no grace. Without running, fighting, sweating, wrestling, heaven is not taken.”

Careful and methodical, Turenne did not share his new allies’ thirst for immediate righteous battle. Rather than heading directly for the Flemish ports, he moved inland again, marching and countermarching through Luxembourg in a fruitless attempt to get Condé to follow. Cromwell, who was used to a more direct and aggressive approach to war, grew increasingly impatient with the Frenchman’s intricate tactics. He threatened to pull his forces out of the alliance if Turenne did not move immediately against the enemy’s coastal positions. Turenne reluctantly agreed, advancing toward Dunkirk in September 1657, by which time illness and desertion had reduced the English contingent by fully one third of its numbers. Cromwell promised to send reinforcements, siege cannons, and extra supplies, and the English fleet mobilized to assist their frustrating allies. On September 19, Turenne’s army drew up on the outskirts of Mardyke, whose fortifications commanded one of the best harbors on the northwestern coast of Europe.

If Cromwell had grown frustrated at the slow developments in the field, he was more than matched in impatience by the never particularly patient Charles II. Exiled to the Flemish backwater of Bruges—known locally as Bruges-la-Morte—the dead king’s heir apparent constantly pressured the Spanish to help him mount a cross-Channel invasion of England. This was no longer in the cards. Cromwell’s navy recently had sunk, off the coast of Cadiz, one of the two so-called “silver fleets” that annually carried back to Spain her ill-gotten booty from the Americas, consigning some 600,000 pounds’ worth of treasure to the watery deep. Without that long-awaited influx of riches, King Philip could barely afford to support himself—his court was said to be dining on fly-blown horsemeat in Madrid—much less take on the additional expense of undertaking an amphibious invasion of England in support of a foppish playboy and his swollen retinue of insufferable courtiers.

Charles Prepares his Forces

Undeterred, Charles drew up increasingly outlandish invasion plans, ranging from a self-led landing in Scotland to the assassination of Oliver Cromwell by a former ally, Edward Selby, whose prickly personality had won him the not entirely admiring nickname, “the Agitator.” Selby fatally compromised his scheme by authoring a 1657 pamphlet openly advocating Cromwell’s violent removal. Giving his work the exculpatory title, Killing No Murder, Selby impudently dedicated it to Cromwell, declaring him “the true father of your country; for while you live we can call nothing ours, and it is from your death that we hope for our inheritances.” Cromwell, unsurprisingly, was not amused by the book and Selby was arrested and thrown into the Tower of London, where he soon died.

With nothing but time on his hands, Charles continued his plotting, corresponding with a shadowy cabal of English Royalists known as “the Sealed Knot” who assured the Pretender that they were ready, willing, and able to rise at his command. Elaborate plans were made, perfected, and discarded, and a standing offer from Charles of 500 pounds a year for life to anyone who could kill Cromwell went unclaimed and unfulfilled. Meanwhile, the would-be monarch wined and dined King Philip’s illegitimate son, Prince Juan-Jose, who had assumed office as governor-general of the Spanish Netherlands. Charles went to concerts, balls, and parties with his new friend, and the two discovered a mutual passion for tennis. Not missing a trick, Charles had one of his scholars draw up a horoscope for the astrology-minded Juan-Jose that flatteringly predicted a crown in his future. But Juan-Jose, like his father, suffered from a notable lack of funds, and even though Charles alternately wheedled or raged about his “scurvy usage” at the hands of his young host, he could do nothing concrete to effect an invasion. Frustrated by the penurious policies of Juan-Jose’s financial adviser, Don Alonso de Cardenas, Charles took to calling the latter “Don Devil.”

Charles had better luck acting on his own, personally raising new forces for the Spanish army. Responding to his call, Royalist forces serving in the various French armies rallied to his colors at Bruges. From the arriving troops Charles formed five regiments—one Scots, one English, and three Irish. His brother James was named lieutenant general and overall commander of the new force, from which originated the two longest-lived regiments in the modern British Army: the Grenadier Guards and the Life Guards. Cromwell’s spies quickly brought him word of the Pretender’s troop-raising, but the Puritans were not particularly concerned. “Of all the armies in Europe there is none wherein so much debauchery is to be seen as in these few forces which the said King hath gotten together,” wrote one observer. “Fornication, drunkenness and adultery were esteemed no sin amongst them.”

The Irish, in particular, were singled out for being “better versed in the art of begging than fighting.” If so, it was a lucky skill for them to have, since the English soldiers in Bruges were at the very end of the Spaniards’ food and supply chain. Of necessity, Spanish troops were quartered at various locations in the Netherlands to prevent them from overdrawing a particular region’s resources. The English, congregated at Bruges, did just that, swarming across the countryside, menacing local residents, and at one point even robbing a Catholic church of its gold plate. They called themselves, without exaggeration, “the naked soldiers.” Besides going hungry—sometimes they ate dogs, if they could get them—the English lacked even the shoes on their feet. Ill fed and ill clothed, they coughed and shivered through the damp Flemish winter. At Damme, on the Sluys canal three miles from Bruges, Charles narrowly escaped death at the hands of a panicky sentry who unloosed a round of buckshot at the approaching party. Charles dodged the fire at the last instant, but two of his courtiers were slightly wounded. All wondered if it was really an accident.

Finally, on September 21, 1657, Turenne’s Anglo-French forces overran the entrenchments outside Mardyke and captured the town. By previous agreement, both the fort and the harbor were turned over to English control. A month later, Juan-Jose arrived on the scene with a relief force that included among its number Charles himself, who had argued his way into the vanguard. A subsequent Spanish counterattack was easily beaten back by Cromwell’s men, and a Puritan cannonball bounded past Charles’s head and disemboweled the horse of the officer beside him.

The Pretender, for his part, was unimpressed. It was Charles’s first taste of combat since he had led the Royalist army to a devastating defeat at Worcester, in western England, six years earlier. That defeat had necessitated six weeks of nonstop flight, with Charles creeping across his putative fiefdom under cover of darkness from attic to outhouse to priest’s hole before he escaped to the Continent. Now he was prevailed upon not to risk the royal personage again in open combat. He readily agreed, spending the winter at Antwerp, where he continued corresponding with plotters back in England and raged anew at the reluctance of Juan-Jose to mount an invasion of the island, failing to notice that the Channel was swarming with Cromwell’s blockaders. The Spaniards, he said, “had grossly failed in all their undertaking to send the King into England.”

Charles’s only success—however minor—was in enticing some of the Protestants in the Mardyke garrison to desert to the royal standard. “You Cavaliers must needs laugh in your sleeves at our dissensions, and the struggle there is amongst us, who shall have the government, and promise your King, not without reason, great advantages from our disagreement,” one disgruntled Cromwellian told his new comrades. That autumn the English commander at Mardyke, Sir John Reynolds, met ill-advisedly with James, the Duke of York, at an informal parley between the lines. The two generals exchanged mere civilities, but Reynolds’s fellow officers were so suspicious of his contact with a member of the despised royal family that he felt compelled to return to England to explain himself to Cromwell in person. On December 5, the ship carrying Reynolds home wrecked on the Goodwin Sands, and he drowned, still unexplained. He was replaced at Mardyke by Maj. Gen. Thomas Morgan, who held no more meetings with the opposing side.

On the Dunes of Dunkirk

After a largely idle winter, Turenne finally broke camp in the spring of 1658, prodded by Cromwell’s insistence on the capture of Dunkirk as a prerequisite for renewal of the Anglo-French pact for another year. In May, Turenne mustered his forces at Amiens and set out for Dunkirk at the head of a 25,000-man army. Juan-Jose, alerted to the movement by his spies, somehow mistook the enemy’s intentions and reinforced Cambrai instead. The English regiment quartering at Cassel was left unprotected, and Turenne’s forces fell upon it and annihilated the Royalists to a man. Charles’s youngest brother, Henry, Duke of Gloucester, commanded the regiment, but he had had the good fortune to fall ill a few months before the surprise attack and thus missed, by two years, his date with destiny. (In September 1660 he would die of smallpox at the age of 21.) Unopposed, Turenne reached the outskirts of Dunkirk in early June and immediately had his men throw up two siege lines, one surrounding the town, the other facing outward to block any attempt to resupply the defenders.

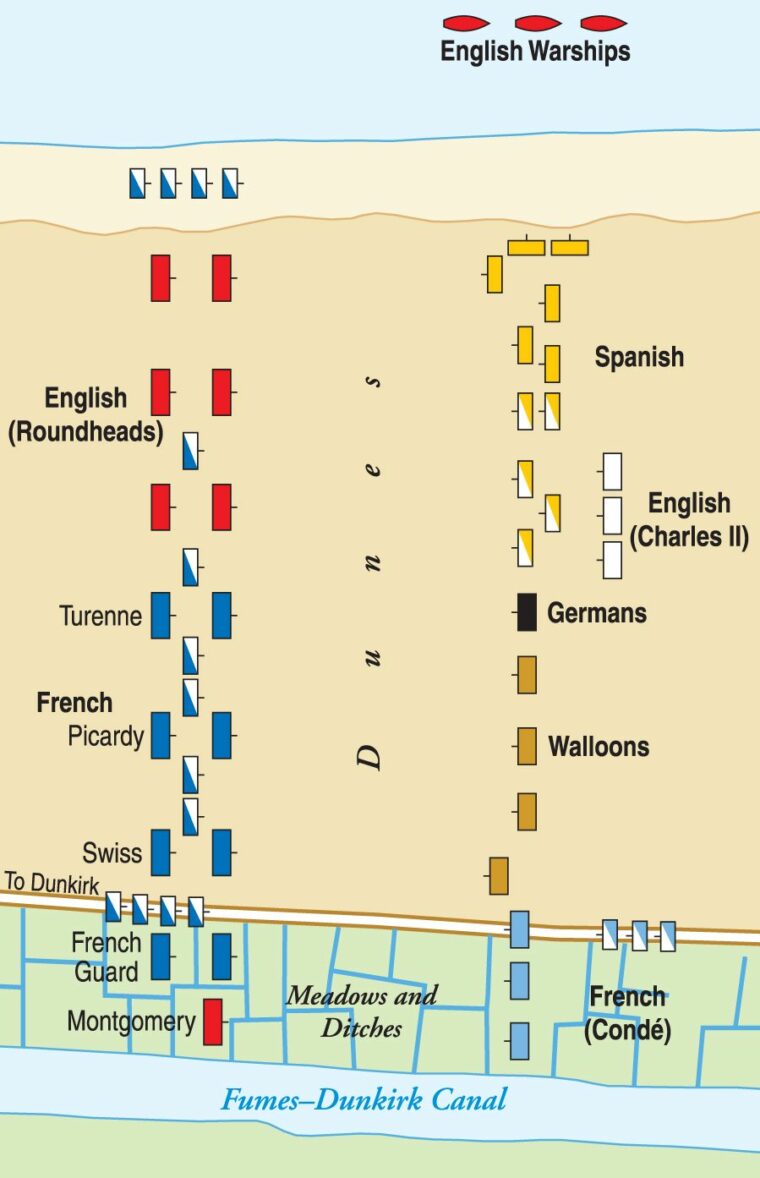

Belatedly realizing his mistake, Juan-Jose hurried to relieve Dunkirk. He had notably fewer men than Turenne—about 16,000 in all, counting the English Royalists. Adding to his problems, the rescuers soon outdistanced their artillery, which was slowed by the marshy, sandy terrain. Nevertheless, on the afternoon of June 13, Juan-Jose pulled up to a crescent-shaped range of sand hills a few miles northeast of Dunkirk and began deploying his troops in two wings. Condé commanded the left, while the Duke of York commanded the right. Juan-Jose did not intend to offer battle until his entire army was in place, but Turenne gave him no choice. For once, the cautious Frenchman moved first. Leaving 6,000 men behind to guard the siege works, Turenne and the rest of the army swung northward to confront the Spaniards in the sand dunes outside Dunkirk. French cavalry deployed on both flanks, and seven English regiments under the command of Lockhart and Morgan massed on the left, supported by fire from English ships lying off in the harbor. Turenne’s forces halted on a low ridge 500 yards from the enemy lines.

The tide was flooding out when Lockhart’s New Model Army soldiers moved into position, their red coats shimmering in the sun. Musketeers and pike men massed together while the Marquis de Castelnau’s French cavalry skirted their wings. A low, insistent murmur in the ranks swelled to a roar, and the English Protestants suddenly broke for the front, shouting their familiar battle cry: “The Lord of Hosts!” Ahead of them waited Spanish general Don Gaspar Boniface’s regiment, supported—as the Englishmen knew it would be—by the hated Royalists of the Duke of York. Hand-picked marksmen began peppering the Spaniards with musket fire as Lockhart led his men up the sandy hillside. The French cavalry swung around to envelop the enemy from the rear.

Startled by the unexpected English charge, Turenne recovered quickly and sent the Marquis de Crequy’s cavalry driving forward on the allied right, while the rest of the infantry surged forward in the center. Meanwhile, Lockhart’s infantry stubbornly climbed the yielding sand dune and pitched headlong into the Spanish defenders. Bitter hand-to-hand combat commenced beneath the broiling Flanders sun. The men on both sides were battle-tested veterans, the English of their country’s civil war, the Spanish of the Thirty-Years’ War, and the French of the three Wars of the Fronde. They knew how to fight.

Once again, religious zeal carried the day. While the Great Condé held his own on the Spanish left, Lockhart’s Roundheads overwhelmed the dune’s defenders and reformed on the hilltop before rushing down the far side. The Duke of York mounted a cavalry charge in reply, but Castelnau’s cavalry got into his rear and sent the whole right wing of the Spanish army into retreat. At the same time, either by divine intervention or careful planning, the tide began rushing back in, making it impossible for the Spanish cavalry to counterattack. The Royalists fell back in orderly but hasty retreat. The Irish Regiment made a brief stand in the center, but Turenne’s larger force soon gained the left flank and rear. Condé, who was an avid card player, could read the way the cards were falling. He withdrew as well. Turenne and his English allies were suddenly masters of the battlefield.

At a remarkably low cost of 400 men, the attacking force had killed or captured more than 10 times that number. Luckily for them, most of the captured English Royalists were swept up by French troops; one unfortunate sergeant fell into Protestant hands and was hanged on the spot as a traitor. The Duke of York managed to get away—the younger Stuarts were proving to be better at escaping than their father, the late king—and retreated to Nieuport. Ten days later, the garrison at Dunkirk surrendered to Turenne, leaving him in complete control of Flanders and the coast. On June 15, King Louis XIV personally handed over the keys of the city to Sir William Lockhart, in recognition of his leading role in the Battle of the Dunes.

The Death of Cromwell

Charles II, waiting worriedly at Brussels, got news of his brother’s defeat and headed precipitately to the Dutch border, where he sought refuge in the elegant little town of Hoogstraten. He was still there two months later, hunting partridges with his fleet of royal hawks, when word arrived from James that Oliver Cromwell, “the great monster,” was dead. The Protestant leader had succumbed on September 3 to a sudden bout of malaria, made worse by overwhelming grief at the death of his favorite daughter, Elizabeth, a few weeks earlier. It would take another 18 months of diplomatic maneuvering before Charles set foot once again on English soil—no thanks to the Spanish, who concluded a separate treaty with France in November 1659. Louis XIV immediately cemented the Treaty of the Pyrenees by marrying Philip IV’s 13-year-old daughter, Maria Teresa, and uniting the two Catholic countries in the bonds of holy matrimony.

Upon his assumption of the throne, one of Charles II’s first acts was to have Oliver Cromwell’s body disinterred from its place of honor at Westminster Abbey and hanged in chains from the thieves’ gibbet at Tyburn on the twelfth anniversary of Charles I’s execution. The corpse was then beheaded, and Cromwell’s head was stuck on a pole outside the abbey, where it remained for the next 20 years, a ghoulish relic of long-delayed, and somewhat redundant, royal revenge. For countless decades, English schoolchildren recited the macabre nursery rhyme: “Oliver Cromwell lay buried and dead,/Heigho! Buried and dead!/ There grew a green apple-tree over his head,/Heigho! Over his head!/The apples are dried and they lie on the shelf,/Heigho! Lie on the shelf!/If you want e’er a one you must get it yourself,/Heigho! Get it yourself!”

In the end, the Protestants’ crushing victory in the dunes at Dunkirk had proved as fleeting and impermanent as a child’s sand castle on a stormy beach. In England, as on the Continent, the tides of fortune had shifted yet again, and another scion of the House of Stuart sat, however uneasily, on the English throne.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments