By Michael D. Hull

When German dictator Adolf Hitler loosed his troops into Poland on Friday, September 1, 1939, he hoped that a lightning conquest would result in a negotiated peace with Great Britain and France.

Hitler’s previous territorial moves during the appeasement years had failed to provoke the two nations into action, so he was stunned when the British and French, honoring guarantees to Poland, declared war on Sunday, September 3. Two decades after the end of World War I, another bloodletting was about to engulf Europe.

But neither side was fully prepared. Britain had a small army and a partly modernized air force, and only her formidable navy was ready to confront an enemy. Germany, on the other hand, boasted a powerful army and air force, but her navy was not up to strength because Hitler, having no experience or interest in naval matters, had ignored the advice of his admirals. They knew that their fleet was hopelessly ill equipped for war. The Führer had, in fact, ordered Grand Admiral Erich Raeder, the Kriegsmarine chief, to be ready for war with Britain by 1944 at the earliest.

When the hostilities started, the German fleet comprised three 11,700-ton pocket battleships, the Deutschland, Admiral Scheer, and Admiral Graf Spee; two battlecruisers; eight cruisers; and 57 U-boats. The force was outmatched by the 23 capital ships, eight aircraft carriers, and 80 cruisers of the British and French fleets. Raeder had decided in May 1939 that the bulk of his fleet would be deployed in the North Sea and the Baltic and that enemy maritime trade would be attacked. As soon as he learned the date of the Polish invasion, he sent his ships to their war stations.

The Graf Spee, under the command of 45-year-old Captain Hans Wilhelm Langsdorff, sailed from Wilhelmshaven on August 21, and the Deutschland followed her three days later. Undetected by the British Home Fleet or patrol bombers of Royal Air Force Coastal Command, the vessels slipped into the Atlantic, ready to raid merchant ships bound for Britain. On August 23, meanwhile, the British Admiralty ordered all warships in home waters to proceed to their war stations, and on August 29 the fleet was ordered to mobilize.

At 11 am on that fateful September 3, the Admiralty telegraphed all ships, “Commence hostilities at once against Germany,” and at lunchtime Berlin followed suit with a signal to Kriegsmarine units: “Open hostilities with England at once.” At the time, the Deutschland and her supply ship were stationed south of Greenland, while the Graf Spee, with her supply ship and oiler, the Altmark, were west of the Cape Verde Islands and heading for the South Atlantic.

The Deutschland and Graf Spee were initially ordered to refrain from hostile acts, and it was not until September 26, when Hitler gave up hope of a quick peace with Britain and France, that they were released for the “disruption and destruction of enemy merchant shipping by all possible means.”

The raiders went into action, but the Deutschland was to prove more of an embarrassment than a help to Germany. After sinking a British freighter on October 5, she committed a major diplomatic blunder by seizing the neutral American merchantman City of Flint. She then sank a Norwegian freighter on the 14th. With two neutrals among her three victims in as many weeks, the Deutschland was ordered home.

In sharp contrast, the Graf Spee proved to be the most destructive of the early naval predators as she preyed on Allied commerce in the South Atlantic. The neutral nations of South America had drawn a 300-mile safety belt that no belligerent warships were supposed to penetrate, but Hitler paid no attention to such restrictions.

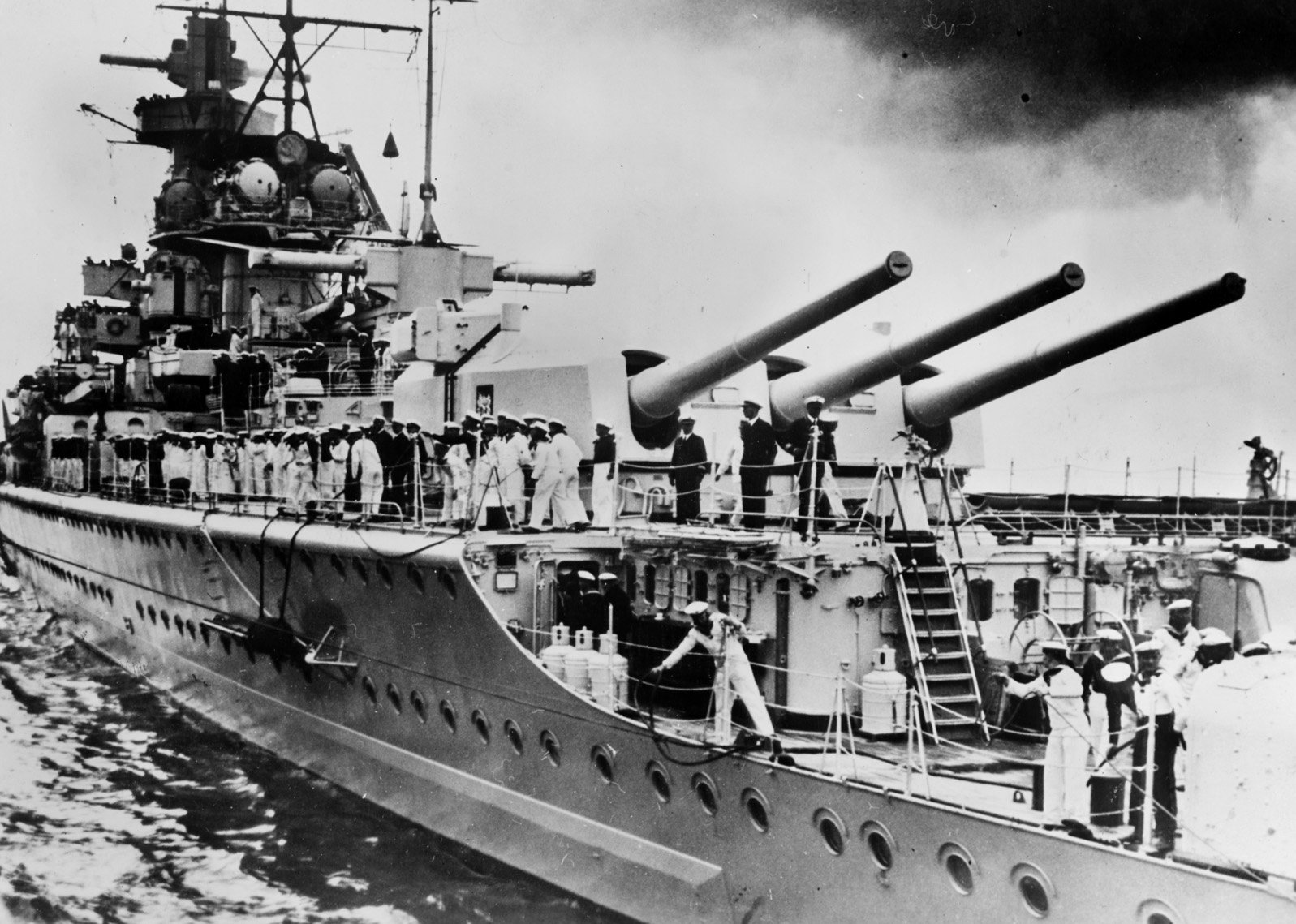

Named for Admiral Graf Maximilian von Spee, who went down with his flagship, the cruiser Scharnhorst, in the Battle of the Falkland Islands on December 8, 1914, the Graf Spee was launched at Wilhelmshaven on June 30, 1934, and was the third and last of the pocket battleships designed to circumvent the arms limitations of the 1919 Treaty of Versailles. She was the proud symbol of Nazi Germany’s resurgent naval power.

Armor plated, three city blocks long, and displacing 16,000 tons with a wartime load of fuel, ammunition, and stores, the Graf Spee mounted two triple turrets of 11-inch guns, eight 5.9-inchers, six 4.1-inchers, eight 19.7-inch torpedo tubes, and two small floatplanes. She had a crew of 1,150 men and a range of 21,500 miles without refueling. Able to cruise at 26 knots, she could outrun any ship she could not outshoot.

A man of intellect and social grace, her captain was a graduate of the Kiel Naval Academy and a cruiser torpedo officer before distinguishing himself aboard the battleship Grosser Kurfurst at the Battle of Jutland on May 31, 1916. Awarded the Iron Cross, Second Class, he later commanded a minesweeper flotilla and torpedo boats in Spanish waters. A comrade cited his “calm and well balanced personality, together with his keen sense of humor and his tactical and strategic training.”

Five days after sinking a British freighter off Pernambuco on September 30, 1939, the Graf Spee seized another and then sank two more. After refueling, she dispatched a freighter on the Cape Town-Britain route and then moved into the Indian Ocean. Ten days produced no prey, so Langsdorff headed into the Mozambique Channel and sank another freighter. After respecting the neutrality of a Dutch vessel the next day, he concluded that enough had been done to alert the British of his presence. So he steered back to his refueling area in the South Atlantic.

Leaving the victim ships’ prisoners aboard the Altmark, Langsdorff headed back to the African coast in November and swiftly dispatched three more merchantmen. By December 7, 1939, in nine weeks of cruising thousands of miles, the Graf Spee had sunk nine merchant ships totaling 50,000 tons. To the credit of her captain, a relentless foe yet honorable man, not one life had been lost.

Because of scant news of the merchant ships’ fate, it was not until early October that the Admiralty became aware of the mercantile marauding by Raeder’s pocket battleships and cruisers. On October 5, the British and French formed nine small hunting groups to track and intercept the raiders, with the deadly Graf Spee as the primary target. The first of several dramatic Royal Navy pursuits during World War II was underway.

The squadrons included a French battleship, British and French cruisers, and aircraft carriers. For several critical weeks, the Allied ships were searching for a needle in a haystack. The hunting groups sailed to the last reported positions of merchant ships sending out “raider” distress signals and then raced to the attacker’s last reported position. The elusive Graf Spee, meanwhile, had slipped back into the Atlantic.

The Allied ships kept searching, and the shrewd Langsdorff continued to elude them. Finally, on December 2, the Graf Spee seized the British freighter SS Doric Star, which was able to transmit a signal that was picked up. It indicated that the general area of the pocket battleship’s operations was off northern Brazil. Vice Admiral Sir G.H. d’Oyly Lyon, the commander of South Atlantic operations, immediately ordered a search northward, while Commodore Sir Henry Harwood, the 51-year-old leader of Force G, surmised that the Graf Spee would make for the rich shipping lanes south of Brazil, off the mouth of the River Plate between Uruguay and Argentina.

A thickset and brave officer with a flair for innovative tactics, Harwood hoped to deal with the Graf Spee himself. He had trained his squadron to divide the pocket battleship’s fire, with two divisions attacking from separate directions. Like his foe, Harwood had been a torpedo officer in World War I and served aboard the armored cruiser Sutlej and the battleship Royal Sovereign. He later commanded the destroyer Warwick and the cruisers London and Exeter before being promoted to commodore. He was described by fellow officers as a man of energy, cool nerve, and cheerfulness. He “had a gift for winning the confidence and esteem of all he met,” said one.

Harwood assembled his squadron off the River Plate on December 12. It comprised the 8,390-ton heavy cruiser HMS Exeter with 8-inch guns and the 7,270-ton Leander-class light cruisers HMS Ajax and the New Zealand-manned HMNZS Achilles, each with 6-inch main guns. His fourth cruiser, the 9,870-ton HMS Cumberland with 8-inch guns, was refitting in the Falkland Islands.

Shortly after daybreak on Wednesday, December 13, the Ajax sighted a plume of smoke to the north. The Exeter was sent to investigate, and at 6:15 am her skipper, Captain F.S. Bell, signaled, “I think it is a pocket battleship!” It was, in fact, the Graf Spee, east of the River Plate estuary. The British ships, though heavily outgunned, immediately began to pursue her. The Exeter shadowed her from the south, while the Ajax and Achilles shadowed from the east. Flying his flag on the Ajax, Commodore Harwood was implementing a preconceived plan designed to divide his powerful opponent’s attention and prevent her from training her big guns on each ship in turn.

Instead of keeping his distance and picking off his attackers at long range, Captain Langsdorff decided to close with them. The British guns opened fire at maximum range, and, as Harwood had hoped, the Graf Spee responded by dividing her salvoes against both groups of ships. Soon afterward, the German vessel turned all her fire against the Exeter, which was perceived as the most dangerous threat with her eight-inch guns. Grave damage was inflicted.

Struck by seven 11-inch rounds, the cruiser lost the use of two of her gun turrets, suffered damage to her bridge and main steering, and was burning. The gallant Captain Bell decided nevertheless to move in on the Graf Spee and attract all of her attention, allowing the light cruisers to attack unnoticed from a different angle. At her maximum speed of 32 knots, the Exeter raced toward the pocket battleship to attempt a torpedo attack. Listing badly to starboard, she was forced to withdraw from the action and limp southward to the Falklands for temporary repairs. Of her complement, 61 were killed and 23 wounded.

While the Cumberland raced northward from the Falklands to join the action, the Ajax and Achilles darted in to distract the German ship, firing six-inch salvoes while receiving rounds from the Graf Spee’s secondary 5.9-inch guns. Hits were made on the pocket battleship. Confined in her holds were 60 captured British merchant seamen, and when she shuddered violently from the impact of Royal Navy shells they cheered wildly.

However, the two light cruisers were taking a worse beating. Half of the Ajax’s main batteries were knocked out, and the Achilles suffered serious damage. The casualties were seven dead and five wounded aboard the Ajax, and four dead in the Achilles. Commodore Harwood then put up a smokescreen to confuse the enemy gun layers and withdrew out of range of the Graf Spee’s main guns.

The furious encounter lasted for just over an hour, and when it seemed that the Germans were winning Langsdorff decided to break off the action. A 14-hour running fight ensued when, pursued by the Ajax and Achilles, he took the Graf Spee southwestward for emergency repairs in the neutral waters off the Uruguayan port of Montevideo. It was late at night that Wednesday, December 13, when she limped into the broad River Plate estuary off Montevideo. She had expended most of her ammunition, and her tired engines were in dire need of an overhaul.

The ship, scorched and blackened by shell blasts, had taken two dozen hits in the battle. There were holes at her starboard waterline, her control and fighting towers had been damaged, and a gun tower on the port side had been torn off. Thirty-six of her complement had been killed and 60 wounded. The morale of Langsdorff’s crew—away from home for four months—was at low ebb. Neutrality laws permitted the vessel to stay in the port for 24 hours, after which she would be forced to leave and face the British ships.

Harwood’s remaining two cruisers, meanwhile, stood off the River Plate mouth while he signaled for reinforcements and waited for HMS Cumberland to join the small force. She arrived on December 16, to be followed by the cruisers HMS Dorsetshire and HMS Shropshire from the Cape of Good Hope on December 19. More British ships also hastened toward the River Plate, including the venerable battlecruiser Renown, the carrier Ark Royal, the cruiser Neptune, and the destroyers Hardy, Hostile, Hasty, and Hereward.

In Montevideo, meanwhile, after Captain Langsdorff had buried his dead, secured hospital care for the wounded, and freed his British prisoners, his damage control crew started to repair the battered ship. He and German Minister Otto Langmann requested 15 days in which to complete the work. Langsdorff needed his ship to be made both seaworthy and combat ready. The Uruguayan government insisted that Langsdorff leave within two days or be interned with his crew.

The Hague Convention allowed a belligerent warship to stay in a neutral port for more than 24 hours only if she had suffered damage, in which case she might “carry out such repairs as are absolutely necessary to render her seaworthy, but may not add to her fighting force.” The repair work started on the morning of Thursday, December 14. Langmann and his aides, meanwhile, tried vainly to win an extension from Uruguay and Argentina, triggering a period of hectic diplomatic wrangling.

While Harwood’s cruisers waited patiently outside Montevideo harbor, diplomatic representatives watched every move closely. The British minister, Sir Eugene Millington-Drake, argued that since the Graf Spee had steamed at high speed for about 300 miles after the battle she was clearly seaworthy and should not be allowed to remain for more than 24 hours. BBC radio broadcast reports that other naval units were closing in to finish off the Graf Spee, and the drama heightened. American commentators and newsreel crews gathered in Montevideo, and the tense standoff captured front page and radio attention around the world.

Through the German embassy, Uruguayan officials eventually granted the pocket battleship an extension of 72 hours, but Langsdorff was frustrated. His sources told him that the River Plate was already blockaded by the Renown and Ark Royal, and his gunnery officer said he could see these ships from the Graf Spee’s control tower. Realizing that the situation was desperate and unwilling to lead his officers and men to almost certain death outside the harbor, the German skipper cabled Berlin on Saturday, December 16, and asked Admiral Raeder for orders. He said that there was “no prospect of breaking out into the open sea and getting through to Germany.” He added, “If I can fight my way through to Buenos Aires, I shall endeavor to do so.”

Raeder replied, “Attempt by all means to extend the time in neutral waters. Approved [to fight your way through to Buenos Aires if possible]. No internment in Uruguay. Attempt effective destruction if ship scuttled.”

As the repairs were going ahead at full speed that Saturday, the hard-pressed Langsdorff faced yet another crisis—the threat of mutiny. Officers protesting the scuttling order called for volunteers to go out and fight, but only 60 stepped forward; the rest stood sullen. Between 3 pm and 7:30 pm, the crew was mustered on deck eight times. The young sailors shouted, broke ranks, and refused to return to duty. The captain intervened, and about 900 officers and men were transferred to the SS Tacoma, a Berlin-Amerika Line freighter-tanker lying in the estuary.

Langsdorff’s only hope was to fight his way across the River Plate estuary to Buenos Aires. Pro-German sentiment was strong in Argentina, and he could expect benevolent neutrality. Raeder told Hitler of Langsdorff’s predicament, and the Führer was irritated by the attention it was receiving. He forbade internment and agreed that the Graf Spee should be scuttled if necessary.

Captain Langsdorff accepted his fate early on the morning of Sunday, December 17. Secret documents and equipment aboard the pocket battleship were destroyed, valuables removed, and scuttling charges placed in several of her large compartments. Shortly after 6 pm, the skipper gave the order to weigh anchor.

Manned by a skeleton crew, with her battle colors hoisted, and followed by the Tacoma, the Graf Spee slid slowly into the powerful stream of the River Plate. Thousands of people lined the riverbanks in silence as daylight faded. Poised in international waters downstream, the cruisers Ajax, Achilles, and Cumberland went to action stations, swung their six- and eight-inch guns, and waited for the German ship. Commodore Harwood was ready to fight a second round.

“It was a glorious evening with a vivid sunset,” reported the gunnery officer aboard the Ajax. “We were closed up and loaded, ready for whatever might come. We received the news that she had sailed. We could hear the Yankee broadcasters describing us as the suicide squadron with their little pop-guns.”

Just as the sun began to go down, the Graf Spee altered course sharply to the west, stopped on the three-mile boundary, and dropped anchor. The time fuses were set, and Captain Langsdorff and his skeleton crew left in boats to be picked up by the Tacoma. The skipper was the last to leave the ship.

At 8 pm, the breathless hush along the riverbanks was shattered by the first of a series of explosions as the scuttling charges set off the pocket battleship’s remaining ammunition. A great pillar of smoke from amidships shot skyward, and the blasts rose to a deafening crescendo. Burning fiercely, the ship sank within three minutes in 25 feet of water. She settled on an even keel on the riverbed as smoke and fire shrouded her superstructure.

A London Daily Telegraph correspondent reported, “At that moment, the sun was just sinking below the horizon, flooding the sky in which small gray clouds floated lazily, a brilliant blood-red. It was a perfect Wagnerian setting for this amazing Hitlerian drama.”

Later, after further wrangling with Montevideo officials and interference by a Uruguayan warship, the Tacoma carried Langsdorff, head bowed and shedding tears, and his crew to Buenos Aires, where they were interned. The sailors were to remain there until February 1946, when 900 of them who had chosen not to stay in Latin America were repatriated to Germany aboard the liner Highland Monarch. She was escorted, in a touch of irony, by HMS Ajax.

Shaken and depressed, meanwhile, after having to destroy his ship, and criticized in some newspapers for not going down with her, Captain Langsdorff wrote letters to his wife, his parents, and the German ambassador in Buenos Aires. In the last of these, he explained, “I reached the grave decision to scuttle the Graf Spee to prevent her falling into the hands of the enemy. With the ammunition remaining, any attempt to break out to open water was bound to fail. Therefore I decided to bear the consequence. A captain cannot separate his own fate from that of his ship. I can do no more for my ship’s company…. I am fully content to pay with my life for any possible discredit on the honor of the flag.”

Langsdorff addressed his men on the afternoon of Tuesday, December 19, made sure that they were safely interned at the Immigrants Hotel in Buenos Aires, and then had a few drinks that evening with his remaining officers and local German residents in the Argentine Naval Arsenal. Then he went to his room there, draped the ensign of Kaiser Wilhelm’s navy around his shoulders, and, in the early hours of December 20, shot himself in the head with his service revolver. He was buried with full naval honors in Buenos Aires.

Hitler’s response to the scuttling and Langsdorff’s suicide was sour and terse: “He should have sunk the Exeter.” Americans who had been following the unfolding River Plate drama by radio praised the gallantry of the “little cruisers,” and one newspaper called the scuttling “a spectacular admission of defeat.”

Walter Lippman wrote in the New York Herald-Tribune, “The defeat of the Graf Spee is pleasing to all the Americas.” But the U.S. government lodged an official protest in London and Berlin against the intrusion by warships of both sides into a neutrality zone.

The Battle of the River Plate was the first significant naval encounter of World War II, and the destruction of the Graf Spee was a coup for the Royal Navy. The response of the British, after a number of naval setbacks in the first four months of the war, was one of rapture. In the House of Commons, Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain hailed the “very gallant action which has been fought by three comparatively small British ships against a much more heavily armed adversary,” while First Sea Lord Winston Churchill said in a BBC broadcast, “The news which has come from Montevideo has been received with thankfulness in our islands and with unconcealed satisfaction throughout the greater part of the world.”

It was not British shells that had sent the Graf Spee to the bottom, but Royal Navy ships had found her, attacked, and trapped her. Just as the annihilation of Admiral Graf von Spee’s squadron by an avenging British force in the Falklands had brought the first good news from the navy early in World War I, so the demise of his seagoing monument provided the first such uplift in World War II.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments