By William E. Welsh

As the first rays of sunlight chased away the shadows from the base of the high walls surrounding the village of Ravenna in northern Italy on Easter Sunday, April 11, 1512, the French army besieging the town began to form into columns. It was not forming up to attack the walls one more time, but rather to march a short distance south to meet a Spanish relief army that had arrived the day before and entrenched for battle. The French army’s preparations were a noisy affair. Shouts rang out, weapons clanged, and drums and trumpets sounded the advance. The ground, made damp by spring rains, sucked and pulled at the feet of men and horses alike as they marched off to battle.

Despite a shortage of provisions, spirits remained high as the 24,000-strong French army faced its greatest challenge in two months of hard campaigning in the region. Led by its gifted 22-year-old commander, Gaston de Foix, the Duke of Nemours, the French army had crushed local revolts, smashed armies sent to intercept it, and chased off the main Spanish army that now appeared, in light of its previous performance, strangely eager to meet it again in what promised to be a desperate fight on the barren, faceless plain south of the town.

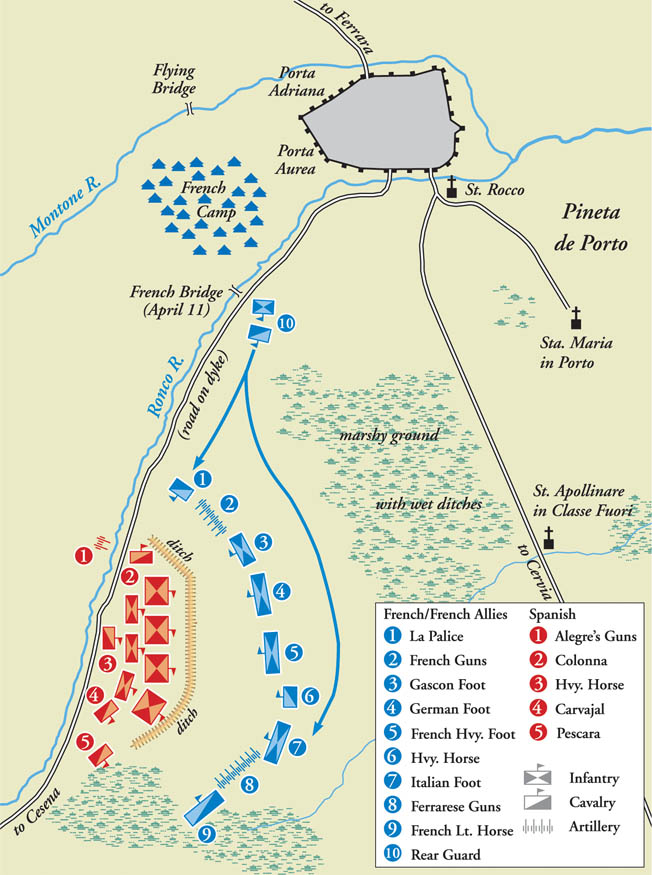

The French army struck south at daylight, marching along the west bank of the Ronco River away from town. A rowdy contingent of mercenaries from southern Germany known as lands-knechts led the way, followed by the French infantry and cavalry and a small Italian force from the nearby Duchy of Ferrara. To reach the enemy, they would have to cross to the other bank of the Ronco. The shallow river posed no real obstacle to mounted or foot soldiers, but its muddy bottom was sure to trap the heavy guns. Since the enemy was on the east bank, French pioneers had toiled away to build a boat bridge capable of supporting the long train of culverins that would play a prominent role in the upcoming battle. Before the horse-drawn guns began rumbling across the bridge, the landsknechts had to gain the other side to protect the army in the event the enemy descended upon it during its passage.

As his men crossed to the opposite bank, the young duke watched with pride. The French commander, the nephew of King Louis XII, rode from one position to the next as he waited for the bulk of his army to cross. At one point, Gaston and those in his company could see the Spanish heavy cavalry arrayed on the opposite bank a mile or so to the south. The leader of the French rearguard, Baron Yves D’Alegre, rode over to Gaston and asked if he could see the enemy’s horse. “Yes, they are in plain view,” replied the young duke. “By my faith, if a man were to bring here but two piece of artillery, he would do them a wondrous hurt,” Alegre said. Gaston concurred and instructed the baron to direct the artillery corps to unlimber a pair of culverins and bombard the enemy from behind once the battle began. The order was among the most significant that Gaston would issue that day, and also one of the last he would ever give.

The French Loss of Naples

For more than a half century, Valois France and Hapsburg Spain had vied for domination of the politically divided Italian peninsula. The first stage of the Italian Wars began when French King Charles VIII led an army into Italy in September 1494 in an unsuccessful attempt to seize the Kingdom of Naples. Almost immediately, a half dozen large and small powers in the region formed the League of Venice to drive the French out of Naples. Fearing that his army would be cornered in Naples and destroyed, Charles began a long retreat to France the following summer. The French won a major battle on the return march when they defeated a League army composed of Milanese and Venetian troops at Fornovo on July 6, 1495.

King Louis XII, who ascended to the throne in 1498, continued the efforts begun by his predecessor to acquire Italian territory. Louis asserted that the Duchy of Milan belonged to the House of Orleans, from which he came, and not to the Sforza family, which had seized control of the duchy a half century before. To back up his assertion, Louis sent a French army under Italian mercenary general Gian Trivulzio to invade the duchy in August 1499. In one month’s time, Trivulzio captured all of the major towns in the duchy, forcing Duke Ludivico Sforza to seek refuge in the Holy Roman Empire.

Unlike the Kingdom of Naples, Milan could be more easily reinforced during times of conflict. The duchy was one of the wealthiest and most prosperous regions of Europe, producing an annual revenue of 700,000 ducats, which Louis planned to use to finance French military operations in Italy. His predecessor’s failure to bring Naples under his control did not deter Louis from making his own attempt to annex the kingdom. In 1500, Louis and Ferdinand of Aragon signed the Treaty of Grenada, in which they agreed to divide Naples between themselves. Under the pact, the French would administer the northern part of the kingdom and the Aragonese would govern the southern part. Although the two sides occupied their respective parts in 1500, Ferdinand turned on Louis almost immediately. War soon broke out between the two sides for control of Naples.

Gonzalo Cordoba, nicknamed “the Great Captain,” was sent by Ferdinand to prosecute his war in Naples. Cordoba, a recognized military genius, devised new tactics for his forces that enabled them to triumph over the French in a decisive victory at Cerignola on April 28, 1503. The following year, Cordoba systematically drove the French from their remaining garrisons in the kingdom.

Refuge in Ravenna

After the Great Captain’s victory over the French, the focus of war in Italy shifted north. The growing power of the Republic of Venice provoked Pope Julius II in 1508 to establish an alliance to counter its expansion. Eager to snap up Venetian lands in eastern Lombardy, Louis opportunistically joined the League of Cambrai, along with Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian and Aragon’s King Ferdinand. The league supposedly was formed to counter the expansion of the Ottoman Empire, but its real intent was to carve up Venice’s holdings in Italy.

In April 1509, Louis led a French army into Venetian territory. After soundly whipping a Venetian army at Agnadello on May 14, the French swept up all of the Venetian holdings in the Po River valley. The victory gave Louis complete control of Lombardy.

Pope Julius at once turned on France, building a strong alliance against Louis. One of the pope’s first moves was to sign a treaty with the Swiss that gave him permission to recruit Swiss mercenaries and forbade them from taking up arms against his forces. In addition to the Swiss, the anti-French league eventually would include England, the Holy Roman Empire, Spain, and Venice. Julius coveted the Duchy of Ferrara and wanted to incorporate it into his papal holdings. First, he excommunicated its ruler, Duke Alfonso. Next, he donned armor and led a Papal Army north in January 1511 to besiege Mirandola and annex Ferrara. The main French army marched to relieve Mirandola, but its commander, Louis D’Ambrosio, sought to negotiate with Julius instead of resolving the matter by force. This ultimately led to the capture of Mirandola by the Spanish-Papal besiegers.

When D’Ambrosio died of illness the following month, command of the French army temporarily went to Trivulzio while Louis reorganized his military leadership. In March, Trivulzio outflanked Julius’s army and advanced on Bologna. As a result, Julius withdrew his army east to Ravenna to prevent it from being trapped. On May 23, the Bolognese, fearing a bloody siege, threw open their gates to the French and the city was captured without a fight.

The French Army Under “The Fox”

The French army in Italy would soon receive a new commander, Gaston de Foix, to serve as viceroy of Milan and assume command of all French forces in Italy. Gaston, nicknamed “the Fox,” was the son of Louis’s eldest sister, Marie. He had been raised at the king’s court, where he received extensive military training. In October 1511, Gaston arrived in Italy to take command of his army and its widely scattered garrisons. His first order of business was to secure Milan against attack from Holy League forces, particularly the Swiss, who were preparing to invade the duchy.

On December 1, a 16,000-man Swiss army invaded the duchy. By mid-month, it was encamped within a day’s march of Milan. As quickly as the Swiss came, they departed, withdrawing without a fight due to lack of support from allied Papal and Venetian forces and a vulnerable supply line against which Gaston’s forces waged constant hit-and-run attacks.

The new year brought threats to French holdings in Lombardy from other sectors. By mid-January, a Venetian army was organizing near Brescia to the east, while a Spanish-Papal army marching north laid siege to Bologna, trapping the French garrison under Alegre. Gaston’s response was to meet the enemy rather than wait for them to come after him. He led his army east in a feint toward Brescia, then quickly turned south to meet the more substantial threat posed by the 20,000-strong Spanish-Papal army under Viceroy of Naples Ramon de Cardona, besieging Bologna.

120 Miles in Nine Days

After a forced march through snow and sleet in which his troops trudged as rapidly as possible over muddy roads and across numerous rivers and streams, Gaston arrived before Bologna on February 5, 1512. Fortunately for the French, the Spanish-Papal forces had not completely encircled the city—the sprawling size of Renaissance cities made it difficult to cover all approaches—and Gaston was able to reinforce the garrison. Cardona, intimidated by the French army and aware that he could no longer capture the city without a pitched battle, withdrew eastward to Imola, leaving behind a large part of his baggage train.

Shortly after Cardona’s departure, Gaston received news that the Brescians had thrown open the city gates to the Venetians, forcing the small French garrison to retreat to a hilltop castle overlooking the city. Likewise, the Venetians were welcomed in Bergamo, a short distance to the northeast. Fearing that the Venetian successes in eastern Lombardy might prompt the Swiss to march again on Milan, Gaston ordered his barely rested troops to prepare for another forced march. Less than 72 hours after their arrival in Bologna, Gaston led his army north along snow-covered roads to Brescia. The French army, reduced by 5,000 men left behind to buttress the Bologna garrison, made good time considering the region was experiencing one of its harshest and dampest winters in memory.

Rather than march immediately to Brescia, Gaston’s army moved straight north to intercept a Venetian force moving to reinforce the city. The French fell on the Venetians near Isola della Scala, east of Brescia. In a short, decisive battle, the French forced the Venetians to retire to the east. Gaston’s army arrived outside Brescia on February 17, having covered 120 miles in nine days.

Securing Bologna

The castle where the French garrison had sought refuge lay outside the town’s walls. The Venetian unit that had seized the town was not large enough to prevent the French relief army from reaching the castle and using it as a base to launch an attack on the city. Gaston’s first move was to offer the townspeople a chance to avoid the whirlwind of revenge that would descend on it for ousting the French garrison. The young duke sent a formal dispatch to the town’s leaders. If they opened the town’s gates immediately, they would be spared the brutal pillaging that would be administered if Gaston’s army had to take the town by force. Unfortunately for the townspeople, the Venetian commander intercepted the correspondence. Without consulting the town’s leaders, the commander replied that the inhabitants refused to surrender. The French decided to attack the following morning.

A driving rain began that night and continued into the morning. At dawn, the French marched down the muddy hillside to assault the city. The Venetians had fewer than 1,500 arquebusiers to man the city’s walls. The French fought their way into the town and slaughtered the Venetian garrison. As was the custom of war at the time, Gaston allowed the 5,000 landsknecht mercenaries to pillage the city over a five-day period. Once the rebellious townspeople of nearby Bergamo learned the fate of the Brescians, they quickly agreed to open their gates to the French and also offered 6,000 ducats to appease the young duke.

After designating a small number of troops to garrison the two rebellious cities, Gaston withdrew to Milan to gather reinforcements and supplies for a fresh offensive. Louis’s orders to Gaston were to destroy the Spanish-Papal army under Cardona and march on Rome. Because the French king needed some of Gaston’s troops to buttress northern France against a possible invasion by English forces, Gaston was urged to resolve the campaign in a short time frame. In late March, Gaston’s army arrived in the Duchy of Ferrara, where it was reinforced by Italian infantry and Duke Alfonso’s 24 guns, which gave the French army a powerful 54-gun artillery train with which to conduct sieges and fight battles.

Besieging Ravenna

Having secured Bologna, Gaston marched directly for Ravenna, a key city in Romagna, arriving outside its walls in the first week of April. The army set up its main camp on the south side of the city between the Montone and Ronco Rivers. Gaston immediately sent a small detachment to take up positions west of the city on the opposite bank of the Montone and had his engineers build a makeshift bridge across the Montone to facilitate communications and troop movements.

As the French went about their siege preparations, landsknecht captain Jacob Empser received an urgent letter from Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian instructing him to immediately break off his service with the French and bring his 5,000 mercenaries back to Germany. Empser, who was loyal to Gaston, showed the French commander the letter, and the two agreed to keep it secret from the other landsknecht soldiers as long as possible.

On Good Friday, April 9, Gaston’s artillery began pummeling the stone walls of Ravenna in an effort to make a breach wide enough for the infantry to fight its way into the town. Once a breach had been made, Gaston ordered his infantry forward. The Spanish garrison repulsed repeated attacks throughout the remainder of the day with great skill and ferocity. Unable to gain a foothold in the city, Gaston called off the attack.

The Spanish Relief Army

The following day, scouts reported to Gaston that the Spanish had arrived from the south and were hastily entrenching on the east bank of the Ronco, one mile south of the French camp. At the same time, Gaston received word that the Venetians had fallen on the French supply line and intercepted a crucial convoy of food and ammunition. In a council of war called to assess the situation, Gaston argued that time was against the French; they must attack the Spanish relief army at once. The French nobles and mercenary captains agreed to march south and strike the Spanish relief force on Easter morning, before it could reinforce the garrison at Ravenna.

Aware that the French had bombards capable of breaking down the city’s walls and that the Ravenna garrison could not hold out for long against the French, Cardona immediately put his army on the road to Ravenna. Taking the advice of chief engineer Pedro Navarro, Cardona planned to allow his men sufficient time to entrench without being harassed by the enemy. The Spanish-Papal army arrived in the vicinity of Ravenna by marching along a causeway on the opposite side of the Ronco. A mile south of the city, the men halted and immediately began to entrench.

Navarro, an experienced engineer commanding the Spanish infantry, ordered his men to dig a defensive ditch and pile the excavated dirt behind it. The Spanish army contained a substantial number of arquebusiers drawn from urban militias and garrisons, and Navarro intended to build a natural fortress that would give them the same protection they would have enjoyed when firing from a city wall or watchtower.

Behind the trench, Navarro ordered his engineers to place 30 two-wheeled carts that mounted five-foot-long arquebuses too heavy for a man to hold. The unwieldy arquebuses were typically mounted through ports or atop walls for the defense of castles or cities, so it was necessary to have a wheeled contraption with which to mount them on the battlefield. The carts had shields for the gunners and spears and scythes attached to the wheels to inflict maximum damage on attackers seeking to overrun the carts. Navarro ordered culverins placed between each cart to shell the attacking infantry. The engineers deliberately left a space on each side between the half-moon-shaped trench and the causeway to allow the Spanish cavalry to launch sorties from protected positions behind the infantry.

Cardona and Navarro knew that the strength of their 17,000-man army was the infantry, which they placed in three lines. The first two lines each contained 4,000 Spanish footmen, while the thinner line contained a mix of 2,000 Spanish and Papal infantry. The 7,000 Spanish cavalry were deployed behind the infantry, ready to sally forth at a crucial moment in the battle when they might turn the tide with well-timed charges. Fabrizio Colonna commanded the vanguard of 2,700 horsemen on the left flank, the Marquis de la Palude led the main battle line of 2,300 in the center, and Don Alfonso Carvajal commanded the 500-horse rear guard on the right. Another cavalry unit led by the Marquis de Pescara and containing 1,500 lightly armed horsemen, was stationed forward on the extreme right flank.

Ravenna had been a bustling port in Roman times but in the intervening centuries the waters of the Adriatic Sea had retreated at a rapid pace, leaving the town five miles from the coast. The plain that stretched south of the city had once been under water, and the soft ground consisted of a mixture of sand and silt. A number of shallow streams and ditches crisscrossed the plain through damp meadows, which the opposing generals knew would make passage difficult for their cavalry. The plain was almost entirely barren of trees, except for a coastal pine grove known as Pineta de Classe south of the city.

Cardona, heavily influenced by Navarro, wanted to keep both his infantry and cavalry inside the fortified camp and allow the French to waste their units in a frontal assault. Even before the battle began, there was disagreement among the generals as to the best strategy. Colonna argued unsuccessfully that the Spanish should attack the French while they were crossing the Ronco and defeat them when they were at their most vulnerable. Although the idea had some merit, Cardona felt that it was at odds with the Spanish army’s traditional tactic of fighting defensively, and he rejected it.

The French Form Their Lines

Once the French army had crossed the Ronco, the vanguard and main battle line turned south, with the infantry companies marching on the right next to the causeway and the cavalry on the left protecting their exposed flank. While the other two formations marched into battle, the rear guard remained at the crossing to function as a reserve and cover a withdrawal if necessary. The French vanguard, led by Siegneur Jacques de La Palice and the Duke Alfonso, comprised 3,600 horsemen, 5,000 German foot soldiers, and 3,500 French infantry. The main battle line was made up of 3,100 cavalry and 3,000 French and Italian infantry. Thomas Bohier, Seneschal of Normandy, commanded the infantry, while prestigious French knights such as Odet de Lautrec, Louis D’Ars, and Siegneur de Bayard led the various horse companies. The rear guard, led by Alegre, had only 300 horsemen but some 4,000 Italian and French foot soldiers.

The French mounted men-at-arms, known as gendarmes, were organized into lances. Each lance was made up of a heavily armored knight, his equally well-armored squire, and two mounted archers armed with crossbows. They fought mounted and were the dominant arm of the French army in the Italian Wars. The lands- knechts were the elite foot soldiers of Gaston’s army. They were recruited from southern Germany and drilled in Swiss heavy infantry tactics to function as shock troops. Although the lands- knechts fought primarily with pikes, there were also a few arquebusiers in their ranks. The French infantry, drawn from Gascony and Picardy, was armed with pikes and crossbows.

In contrast, the core of the Spanish army was its infantry This was partly because the Spanish nobility did not have the wealth to outfit themselves with the costly, lavish armor used by the French gendarmes, and partly because of the difficulty of sustaining a large horse population in the rugged terrain of the Iberian Peninsula. When Cordoba arrived in Naples in 1495, he set about reorganizing the Spanish infantry so that it could compete on more equal terms with the Swiss heavy infantry serving as mercenaries in the French army. The Great Captain substituted pikemen for the traditional sword-and-buckler troops in the Spanish ranks and replaced crossbowmen with arquebusiers. By the time of Ravenna, the ratio of pikes to arquebuses was 6:1, a far lower ratio than in the German and Italian infantry units fighting for the French. Cordoba chose to retain a small number of sword-and-buckler troops to slip in among the enemy formation and cut at the unprotected legs and thighs of the enemy pikemen.

When it was just out of the range of the Spanish cannon, the French army formed into a menacing line of battle. The French vanguard constituted the right wing, and the main battle made up the left wing. The infantry was placed in the center and supported by French heavy cavalry on each wing. The landsknechts were in the center of the battle line, with Gascon footmen on their right and French and Italian infantry on their left. Duke Alfonso sent his artillery to the far side of the battlefield via a circuitous route which enabled it to traverse the marsh and take up position on the French left to enfilade the Spanish right flank.

A Duel of Artillery

Once the French had formed into the line of battle by mid-morning, the two sides began shelling each other. Navarro’s culverins poured round shot the size of oranges into the densely packed French formations, causing considerable casualties on those units on the French right that were the closest to the Spanish guns. A pair of French cannons on the opposite bank of the Ronco returned fire. Alfonso’s guns, once they had crossed to the French left flank, joined the bombardment. The Spanish infantry escaped the worst of the shelling by lying prone at Navarro’s direction in shallow depressions in the landscape. The Spanish cavalry, however, was not so lucky. Having no place to hide, the Spanish knights and genitors suffered painful deaths and gruesome wounds from the French artillery fire. The round shot decapitated some soldiers and tore off the limbs of others. One well-placed shot toppled more than 30 knights at once.

The carnage from the artillery duel was not limited to the Spanish ranks. During the two-hour ordeal, Spanish cannons killed as many as 2,000 French and German foot soldiers—about one-sixth of Gascon’s entire infantry force. In one grisly incident, a cannonball sliced in half two incautious French captains who were conferring in the open between infantry formations. As the carnage dragged on, some of the soldiers became rattled. When a formation of Gascon infantry sought to shield itself behind an adjacent German unit, the landsknechts drove them off with their pikes.

Failed Cavalry Charge

Colonna’s vanguard was under direct fire from a pair of French guns on the opposite bank of the Ronco. The Italian general chafed under the orders he had been given to hold in place until the French attacked. Colonna failed to appreciate that the French were getting the worst of the artillery duel. Looking about at the shattered bodies of many of his best knights, he resolved to lead his men out of harm’s way and avenge the slaughter. He dispatched a messenger to Cardona to request permission to charge the French line while he still had sufficient numbers left with which to attack. Twice, Cardona refused. After the second refusal, Colonna resolved to lead his knights forward without Cardona’s permission.

Colonna was not the only general concerned about his men. Carvajal, whose men were under fire from a larger number of guns on the French left flank, also raged against Cardona’s orders to stay in place. Cavalry captains hurled curses at Navarro, blaming him for fighting a defensive battle. With casualties mounting after nearly two hours of shelling, Carvajal took it upon himself to lead his men onto the open plain through the narrow passageway on the Spanish right. After a quick conference, Pescara instructed his genitors to support Carvajal’s 500 mounted knights. Companies of knights and genitors on the Spanish right soon raced toward Duke Alfonso’s battery on the French left.

Cardona watched aghast as the cavalry companies on the Spanish right flank began charging the French line. Realizing that they were outnumbered, he had no choice but to permit Colonna and La Palude to lead their knights into battle too. Carvajal’s knights were the first to reach the enemy line, engaging the gendarmes of the French main battle. The two forces became intermingled as the mounted melee swirled around Duke Alfonso’s battery. Seeing the need to coordinate the reinforcements, Alegre assumed the role of chief of staff and directed small bands of gendarmes and mounted crossbowmen to reinforce the left flank. These additional troops stabilized the line and gave the French enough strength to drive off Carvajal and Pescara.

While the cavalry melee was swirling about on the French left flank, Colonna’s and La Palude’s knights struck La Palice’s vanguard on the opposite flank near the Ronco. The broken ground over which the Spanish attacked greatly lessened their shock power, and the gendarmes did not suffer severe loss when the two sides collided. Still, Alegre thought the threat dire enough to order the 300 gendarmes under his command at the Ronco bridge to enter the fray.

Spanish losses were heavy on both flanks. Many knights had lost their lances in the first charge and were unable to deliver a hard blow to the French line. The knights on the Spanish right flank abruptly quit the battlefield. Unwilling to return to the confines of the camp, the 100 survivors of Carvajal’s charge rode away from the battlefield, leaving behind 400 dead knights. Both Carvajal and Pescara were wounded in the action. Carvajal escaped with his men to the south, but Pescara was captured by the French and taken to the rear. Colonna had a higher sense of loyalty. After his attack was repulsed, he led his knights back into camp, where they might bolster the Spanish infantry during the next phase of the battle. But Cardona, believing the day was lost, left camp with his escort and followed Carvajal’s men south. Seeing the commander of the Spanish-Papal army quit the battlefield, Colonna flew into a rage and cursed the viceroy for his cowardly actions.

Clash of Infantry

At mid-day, Gaston ordered his infantry to advance. In an effort to soften up the Spanish infantry for the main attack, La Palice sent a large contingent of Gascon crossbowmen with an escort of Pickard pikemen toward the Spanish camp in the narrow corridor between the river and the causeway. His wanted the crossbowmen to use the causeway for cover while showering their fire into the Spanish infantry, who continued to lie prone. Unfortunately for La Palice, Navarro spotted the movement and shifted a number of companies of Papal infantry to check the advance.

After the attack failed, La Palice ordered a general advance by the French and German pikemen. Their numbers were significantly smaller than they had been at the outset of the battle. Of the 8,500 that had formed up at the beginning of the battle, upward of 2,000 had been cut down by Spanish artillery fire. The French advanced on the right while the lands- knechts tramped forward on the left. Their advance was slowed considerably by the presence of a shallow dike that they had to cross before they reached the Spanish position. As they struggled to traverse the ditch, Spanish arquebusiers poured a steady fire into their ranks. Scores of pikemen were mowed down as they crossed the dike. One of the first to fall was Jacob Empser, the landsknecht commander.

One of the landsknecht’s bravest officers, Fabian von Schlabrendorf, swung his pike madly in a wide arc knocking pikes from the hands of about a dozen Spanish soldiers and opening a path into the enemy ranks for his men to exploit. Schlabrendorf fell but the men around him renewed their efforts when they witnessed his feat of bravery. At one point in the melee, Seignur de Molart, the principal captain of the Gascons, was killed. Molart’s death had a devastating effect on the Gascons, and they broke off their attack. Navarro and his officers were able to feed more troops into the battle, and neither the Germans nor the Gascons was able to dislodge the Spanish line or open a breach for the French cavalry.

After they tried unsuccessfully in fierce hand-to-hand combat to force a breach in the Spanish line, La Palice’s foot soldiers retreated a safe distance from the trench to reform. Seeing the attackers pull back, the Spanish infantry raised a large shout to signify their victory. In their desperate initial assault on the Spanish line, the French and German pikemen suffered another 1,200 killed or wounded. Added to its previous losses from artillery fire, La Palice’s foot had lost one-third of its strength.

By the end of the initial melee at the trench, the surviving cavalry of the Spanish vanguard had reassembled behind the Spanish infantry. Similarly, the French mounted gendarmes on both flanks also had reorganized themselves to support of its infantry. The captains of the French and German foot soldiers rallied their men for a second attack on the Spanish line. Despite having wavered previously, the Gascons recovered sufficiently to participate in the second assault. With a shout, the ranks of French and German infantry surged forward. They fought their way through the blood-soaked trench where the mangled bodies of both Spanish and French lay intertwined. On the right, a Gascon captain leaped atop a cart to wave his men forward, but was quickly cut down.

The Spanish Forces Break Ranks

Seeing the front ranks of the Spanish foot giving ground, Colonna issued orders for his mounted knights to follow him in a sortie against the Gascons’ right flank. The cavalry charge created disorder among the retiring Gascons. Sensing an opportunity to finish them off completely, Navarro sent two companies of Spanish pikes to pursue the Gascons across the open ground. The two companies soon found themselves cut off and unable to make a safe retreat back to friendly lines. Spotting the pine grove to the north, they tried to sneak off the battlefield without being spotted by the French rear guard.

Although the French right had received a devastating blow from the combined attack of Spanish horse and foot, the French left remained stable. Its 3,000 French and Italian infantry had not yet been committed to the fight. The Spanish had been able to make gains against the French right largely because La Palice’s gendarmes were still reforming during Colonna’s second sortie. Once they reformed, La Palice’s gendarmes charged directly into the Spanish camp, using the northern entrance before Colonna’s horsemen could cut them off. The Papal infantry from the reserve corps was no match for the French gendarmes, who used the weight of their horses to trample the Papal pikes. When the Papal pikemen scattered, the French gendarmes slammed into the rear line of the Spanish infantry before it could reform.

Sensing the tide of battle turning, the Seneschal of Normandy waved forward the 3,000 fresh pikemen on the French left and, together with the survivors of La Palice’s foot, they made a broad, coordinated attack on the Spanish front line. Facing attack from front and rear, the Spanish companies rapidly gave ground as they sought to extract themselves from the pincers that were squeezing them. Of Navarro’s 10,000 foot, only 2,000 were able to escape the slaughter by forming themselves into squares as they slowly withdrew toward the causeway. The French showed no quarter, striking down all soldiers and officers of low rank. Only Navarro and a small number of high-ranking officers were taken prisoner for the ransoms they might fetch.

A Fatal Pursuit

While the slaughter was unfolding in the Spanish camp, the surviving members of the two companies of Spanish infantry caught behind enemy lines marched rapidly northeast toward the Pineta de Classe where they hoped to slip undetected into Ravenna from the east. Unfortunately, the large body of soldiers eventually was spotted by Alegre’s rear guard. Alerted to the threat, the Bastard du Fay began assembling a force to intercept the escaping troops. Realizing that they would never make it to the Pineta de Classe without being intercepted, the Spanish changed direction and began marching rapidly west to the causeway along the Ronco, where they hoped to fight their way off the battlefield to the south. At that point, some Gascons spotted the escaping Spanish foot and pointed them out to Gaston and his escort of about two dozen gendarmes, all of whom were keenly watching the destruction of the enemy’s camp. The Gascons, thirsty for revenge after such a terrible fight, implored the duke to kill the Spanish foot before they escaped.

Unable to decline the challenge, despite a promise to his close friend Bayard that morning to refrain from further fighting once the day was won, Gaston gave the order for his companions to join in the pursuit. By then, the Spanish soldiers had gained the causeway and braced themselves for the attack. When they reached causeway, the French gendarmes spurred their horses up the incline. Spanish arquebusiers fired a volley that failed to stop the gendarmes. At that point, the pikemen in the front ranks advanced with their poles and unhorsed Gaston and several of his companions. No sooner had Gaston scrambled to his feet than several Spanish soldiers with swords and daggers fell on him, inflicting numerous fatal wounds.

Victory on the Field, Loss of Gaston the Fox

Cardona’s army was nearly wiped out as a result of the battle. The viceroy did not halt his retreat until he reached the northern border of the Kingdom of Naples, where he reassembled the 3,300 survivors of the disaster at Ravenna. Almost all of the Spanish-Papal infantry had been destroyed, likewise all of the heavy cavalry from the vanguard and main battle line. Although Cardona and Carvajal managed to escape by quitting the field, all the other Spanish generals—Colonna, Navarro, Palude, and Pescara—were captured and held for ransom. The total number of Spanish killed, wounded, and missing was 16,700. The French lost about 5,000 men, mostly from the landsknecht companies that had fought so valiantly. In addition to Gaston, Alegre also perished on the battlefield.

Following the battle, the generals and captains elected La Palice, who at 44 was twice Gaston’s age, to lead the French army in Italy. Louis XII subsequently ratified the vote. Unfortunately, La Palice possessed none of Gaston’s military genius. In the days following the battle, all but 800 landsknechts in the French service returned to Germany in compliance with Maximilian’s orders. The reduction in French infantry strength was followed by the news that the Swiss had once more invaded Lombardy. Although the victory at Ravenna gave La Palice a new supply base from which to make an audacious thrust toward Rome and force Pope Julius and his allies to sue for peace, La Palice was not a risk-taker. Instead, he chose to countermarch to the Duchy of Milan.

When La Palice reached Milan, he found the city in full revolt. With Swiss and Venetian units harassing his columns, La Palice pushed toward Asti, where he hoped to regroup. As the French army was making a river crossing, enemy forces bore down on it. Panic gripped the French forces, who crowded onto a narrow bridge that collapsed under their weight. Finding themselves outnumbered, a large portion of the French stranded on the opposite bank chose to surrender. By June, the Holy League had driven the French forces from the Duchy of Milan and negated all of Gaston’s hard-won achievements at Ravenna. In the end, Gaston the Fox had died for nothing.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments