By Victor Kamenir

French Marshal Michel Ney found himself outmatched in a clash of arms with a Swedish-Prussian army at Dennewitz 40 miles southwest of Berlin on September 6, 1813. Four days earlier French Emperor Napoleon I had sent Ney with 58,000 troops in three corps to capture Berlin and knock Prussia out of the War of the Sixth Coalition. Ney fell into a trap and found himself fighting the combined strength of former French Marshal Jean-Baptiste Bernadotte, by then Sweden’s Crown Prince, and Lt. Gen. Friedrich Wilhelm Freiherr von Bulow.

The battle began when French General Henri Bertrand’s IV Corps struck the Prussian vanguard consisting of Lt. Gen. Bogislav von Tauentzien’s corps in the late morning. Bulow arrived 90 minutes later with the main force and launched a sledgehammer attack on the French left flank. When General Jean Reynier’s VII Corps came up, Ney counterattacked. Bulow committed the rest of his troops, and the French fell back. The tide of battle favored the French when Marshal Nicolas Oudinot’s XII Corps, the third and last of the French corps, arrived on the field.

Instead of remaining behind his lines to direct his forces, the impetuous Ney joined the battle once all of his troops were up. Not appreciating the danger to his left flank, Ney mistakenly ordered Oudinot to shift his corps from the French left to the French right. Both wings of the French army fell back in the face of furious attacks by the Prussians, and when Bernadotte’s vanguard arrived after a 15-mile forced march, its 36 cannon shattered the French left flank. Ney lost 24,000 men and 50 guns. “The spirit of [our] generals and officers is shattered and our foreign allies will desert at the first opportunity,” he wrote to Napoleon after the defeat. The unflappable Napoleon received the news stoically, but in private he fumed over Ney’s incompetence.

The battle at Dennewitz was part of a strategic plan put in place by the Allies after they suffered a series of defeats in summer 1813 at the hands of Napoleon. The Trachenberg Plan, an amalgamation of existing Austrian, Russian, and Swedish strategies hammered out by the Allied monarchs and senior generals at a meeting at Trachenberg Castle in Silesia in July 1813, called for deliberately avoiding battle with Napoleon while actively seeking battle with his marshals, such as Ney at Dennewitz, entrusted with independent command. In the meantime, the Allies planned to consolidate their various armies in eastern Germany to give themselves overwhelming power and strength for such a time when they decided to take on Napoleon again in a set-piece battle.

The situation in central Europe had changed dramatically in just a year’s time. In June 1812 French Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte had led the 500,000 troops of his Grande Armée into Russia. Lt. Gen. Mikhail Kutusov’s Russian army withdrew in the face of his bold advance; and as they did so, they conducted a scorched-earth strategy designed to deprive the Grande Armée of the food and forage necessary to sustain its campaign. After the inconclusive clash at Borodino that resulted in staggering losses for both armies, Napoleon entered a nearly deserted Moscow that hardly could be regarded as a strategic victory. Fires destroyed the city in September, and the starving French army began its tragic retreat on October 19. When the worn out soldiers of the Grande Armée stumbled back across the Berezina River in late November, just 35,000 remained in the French ranks. Turning over command to Marshal Joachim Murat, Napoleon left his troops on December 5 and hurried to Paris in order to raise a new army.

From that point on, Russian Emperor Alexander I, who had declined Napoleon’s offer of peace while his troops were on Russian soil, became his implacable enemy. After a brief halt at the border to rest and receive reinforcements, the Russian army crossed into East Prussia on December 30. Alexander, who had once been Napoleon’s ally, accompanied his troops as they entered Prussia. With the myth of Napoleon’s invincibility shattered, Prussia rose up against Napoleon. Prussian General Ludwig Yorck von Wartenburg, who commanded a Prussian auxiliary force sent to fight with the Russians, signed a truce with the Russians on December 30, 1812, and the two powers soon signed a military alliance. Prussian King Frederick William III then declared war on France on March 7, 1813.

Napoleon’s new army comprised survivors from the Russian campaign, veteran troops from Spain, National Guard troops, and the conscripts of the class of 1813. By mid-April 1813, the French emperor had scraped together an army of 225,000 men. The army, however, bore no resemblance to the veteran army that had invaded Russia. Tens of thousands of teenage recruits, nicknamed “Marie Louises” after their teenage empress, lacked combat experience and suffered from low morale. Battalions had been cobbled together into provisional regiments. These regiments lacked unit cohesion; that is, the soldiers lacked the bond that came from serving together in the field, had no sense of commitment to the unit, and did not have a shared sense of mission and purpose. As for the Grande Armée’s cavalry, catastrophic loss of horses during the Russian campaign prevented Napoleon from completely rebuilding that branch of service. This would severely restrict the ability of Napoleon and his marshals to conduct reconnaissance operations and pursuits in the coming campaign.

The princes of the small German states welded by Napoleon into the Confederation of the Rhine in 1806 remained loyal, albeit apprehensive, and fielded contingents from Baden, Berg, Hesse-Darmstadt, Westphalia, and Wurttemberg. King Frederick Augustus I of Saxony placed a division of infantry and division of cavalry under Napoleon’s command. Napoleon also received from his allies an Italian division and a Polish corps under Lt. Gen. Josef Poniatowski.

In the first two major battles of the 1813 campaign, Napoleon defeated combined Russo-Prussian armies in Saxony at Lutzen on May 2 and at Bautzen on May 21. Both sides needed a breather. Napoleon proposed an armistice, which was welcomed by his adversaries, and the two parties concluded the agreement on June 4.

The cease-fire ended on August 11 when Austria and Sweden declared war on Napoleon. The Sixth Coalition arrayed against Napoleon included Russia, Prussia, Austria, Sweden, Great Britain, Portugal, Spain, and a number of small German states. With Great Britain, Spain, and Portugal engaged against the French forces in Spain, it fell to the Russian, Prussian, Austrian, and Swedish armies to go to war against Napoleon’s newly raised Grande Armée in Central Europe.

The Trachenberg Plan called for organizing the Allied forces into three independent armies converging from several directions to entrap Napoleon and ultimately force him into a decisive battle where he would be crushed under the weight of their superior numbers. Whereas Napoleon would be lucky to field 160,000 troops, the Allies could assemble twice that number.

The childless Swedish King Charles XIII had adopted Bernadotte as his heir in 1810. As the Swedish Crown Prince Charles John, Bernadotte commanded the Army of the North made up of Russians, Prussians, and Swedes. Prussian Field Marshal Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher led the Russo-Prussian Army of Silesia situated between the Army of the North and the Army of Bohemia.

The Army of Bohemia, which was the largest of the three armies, comprised Austrians, Russians and Prussians. Austrian Field Marshal Karl Philip, the Prince of Schwarzenberg, not only commanded the Army of Bohemia but also had overall command of the three armies. The three rulers, Russian Emperor Alexander I, Austrian Emperor Francis II, and Prussian King Frederick William III, accompanied Schwarzenberg and established their headquarters at Rotha.

General Levin August von Bennigsen, the German-born commander of Russia’s Army of Poland had received orders to march as rapidly as possible to reinforce the three armies on the front. General Hieronymus von Colloredo-Mansfeld, who commanded an Austrian corps, also had orders to conduct a forced march to the battlefront as part of the Allies’ quest to bring all available manpower to bear against Napoleon’s restored Grande Armée.

Napoleon’s plan was to defend the line of the Elbe River. He considered the overall situation as favorable to him. He could operate on shorter lines of communications than the Allied armies, which would need at least six days to concentrate their forces. Having established his base at the fortified Saxon capital of Dresden, the French emperor intended to defeat Allied armies piecemeal.

Adhering to the Trachenberg Plan, the Allies defeated French marshals at Grossbeeren, Katzbach, and Kulm over a two-week period from August 23 to September 6. Yet when Schwarzenberg’s Army of Bohemia found itself assailed by Napoleon at Dresden on August 26-27, it suffered a sharp defeat. Napoleon did his very best to rush with the main army to the support of threatened outlying corps, only to find the Allies would withdraw when he approached. The constant marching and countermarching quickly wore out the raw recruits in the French army.

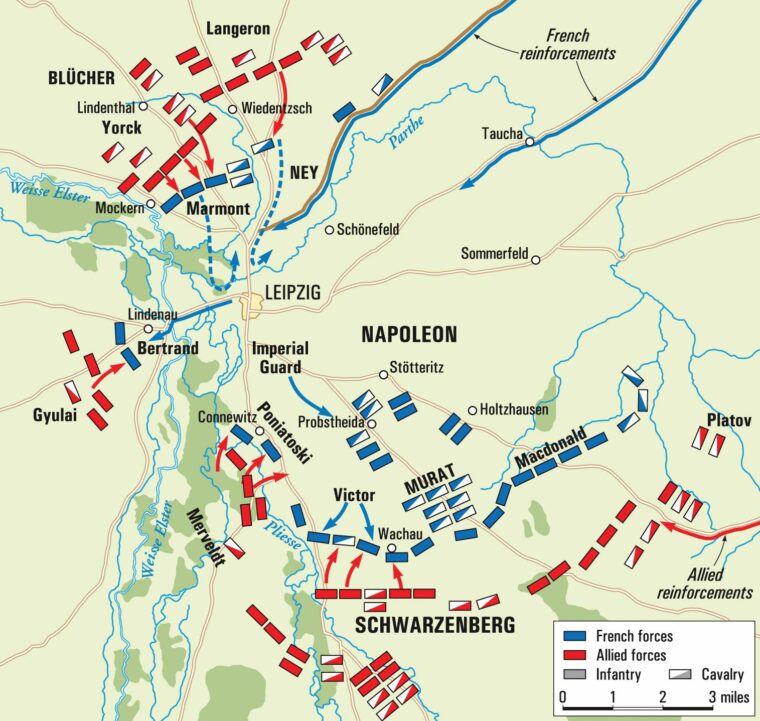

With the Allied ring tightening around him, Napoleon withdrew in the direction of Leipzig, where Marshal Joachim Murat’s independent command had taken up a position south of the city. Aware that Schwarzenberg’s Army of Bohemia was the closest Allied army to Leipzig, Napoleon planned to defeat Schwarzenberg first. After he accomplished that objective, Napoleon intended to remain in the Leipzig area and turn to face Blücher and Bernadotte, whose armies were moving south. Although Napoleon was aware that Blücher and Bernadotte were marching separately, his meager cavalry resources prevented him from conducting thorough reconnaissance. For that reason, he was unaware just how close Blücher was to Leipzig.

Napoleon arrived at Leipzig at midday on October 14. Situated 75 miles west of Dresden, Leipzig occupied a position at the confluence of the Elster and Pleisse rivers. From a geographical standpoint, the Elster and Pleisse, combined with the Elster tributaries, the Luppe and Parthe, divided the surrounding country into four sectors corresponding to the four points of the compass.

The countryside consisted of scattered villages and hamlets with stone houses, churches, and chateaus that served as ready-made fortified positions. Although the ground in the immediate vicinity of the rivers was marshy, there were wide stretches of open ground to the south and east that were well-suited for cavalry operations. Even so, the area between the Elster and Pleisse was particularly swampy, and the Elster was only passable over the causeway at Lindenau.

As Napoleon entered Leipzig, he heard the crash of musketry to the south, where Murat had become hotly engaged against a reconnaissance in force by Schwarzenberg’s Army of Bohemia. After a day of heavy fighting around Liebertwolkwitz on October 14, where one of the largest cavalry clashes of the Napoleonic Wars took place, Murat held fast to his positions.

After concentrating all of his immediately available forces, at the end of October 14, Napoleon had 177,000 men and 690 guns at Leipzig, with 13,000 men in Reynier’s VII Corps and 4,200 men in General Antoine Guillaume Delmas’ division of Marshal Joseph Souham’s III Corps on the way. In contrast, the Allies had a total of 334,000 and 1,500 guns, the combined total of the three armies that would be on hand for the battle. Schwarzenberg’s Army of Bohemia, which was already in the Leipzig area, numbered 203,000 men. Blücher’s 64,000-strong Army of Silesia was fast approaching and was expected to be on hand soon. Last but not least, the 67,000 troops of Bernadotte’s Army of the North followed Blücher’s army.

Both sides spent October 15 deploying their forces and making plans for the anticipated battle the next day. After completing his dispositions, Napoleon put Murat in overall command of the southern sector. Marshal Claude Victor’s II Corps and General Jacques Lauriston’s V Corps were situated between the villages of Wachau and Liebertwolkwitz.

In reserve behind Lauriston were 2nd Old Guard Division under General Philibert Curial, I Young Guard Corps under Marshal Nicolas Oudinot, II Young Guard Corps under Marshal Edouard Mortier, and Guard Artillery under General Antoine Drouot. The IX Corps under Marshal Charles-Pierre Augereau, the 1st Old Guard Division under General Louis Friant, the Guard Cavalry under General Etienne Nansouty, and the I Cavalry Corps under General Victor Latour-Maubourg were stationed further back at the village of Probstheida.

In the sector between Connewitz and Markkleeberg were the VIII (Polish) Corps under Jozef Poniatowski and IV (Polish) Cavalry Corps. In the southeastern sector near Holzhausen were the XI Corps under Marshal Etienne MacDonald and General Horace Sebastiani’s II Cavalry Corps.

Marshal Michel Ney had overall command of the northern sector of the French army at Leipzig. His forces consisted of Souham’s III Corps, Marshal Auguste de Marmont VI Corps, General Henri Bertrand’s IV Corps, and General Jean-Toussaint Arrighi’s III Cavalry Corps. The 27th Polish Infantry Division under General Jan Henryk Dabrowski, which was detached from the VIII Corps, was deployed at Weideritzsch.

Napoleon had established a line of outposts to the east and northeast to furnish advance warning of the arrival of any Allied forces and to watch for the arrival of Reynier VII Corps and Delmas’ division that were escorting supply and artillery trains from Duben.

Napoleon intended to take the initiative and attack the Allies. He first intended to pin Schwarzenberg in the southern sector between the Pleisse and Parthe rivers. Once this was done, he would dispatch MacDonald’s and Sebastiani’s corps to envelop Schwarzenberg’s right flank. If needed, further troops from the north sector would be brought up to reinforce MacDonald and Sebastiani to deliver the final blow.

If forced to retreat, Napoleon intended to withdraw northeast towards Torgau in order to link up with Reynier and Delmas. With that in mind, he placed his supply trains and artillery parks to the northwest of Leipzig. As a forethought, Napoleon placed cavalry pickets from Arrighi’s III Cavalry Corps to guard the causeway at Lindenau on the west bank of the Elster River at the head of the causeway in case the army needed to withdraw southwest toward Weissenfels on the Saale River.

The Allied plans for October 16 called for the main attack to be delivered along the right bank of the Pleisse River against the line of Markkleeberg, Wachau, and Liebertwolkowitz. Schwarzenberg gave the task to Russian General Barclay de Tolly with the bulk of the Army of Bohemia’s troops.

Barclay’s forces consisted of Austrian IV Corps under General Johann Klenau, nine Cossack regiments under General Matvei Platov, and a combat group under Russian General Peter Wittgenstein. The Russian combat group was made up of General Mikhail Gorchakov’s I Corps, General Prince Eugene of Wurttemberg’s II Corps, General Friedrich Kleist von Nollendorf’s Prussian II Corps, and General Paul Pahlen’s Russian Cavalry Corps.

Stationed at Rotha were reserves under Russian Grand Duke Konstantin, Alexander I’s brother. These reserve forces consisted of the Russian III (Grenadier) Corps under General Nikolay Rayevski, Russian-Prussian V (Guard) Corps under General Aleksey Yermolov, and Russian Cuirassier/Guard Cavalry Corps under General Dmitry Golitzin.

In the center, between the Pleisse and Elster rivers, General Maximilian Merveldt’s Austrian II Corps would advance between the Pleisse and Elster rivers against Connewitz. Austrian III Corps under Field Marshal Ferenc Gyulai was to advance along the west bank of Elster to Lindenau. Separated by two rivers, the three Allied forces were to operate largely independent of each other.

On the morning of October 16, on the assumption that Blücher was still some distance away, Napoleon ordered Ney at 7 a.m. to send Marmont’s VI Corps from his position in the northern sector to a location between Leipzig and Liebertwolkwitz. This move would place Marmont in position to support either the attack by MacDonald’s and Sebastiani’s corps against the Allied right flank or support Gyulai’s corps at Lindenau should it come under Allied attack.

After the fog dissipated, the action began with Barclay pushing forward along the right bank of the Pleisse. On Barclay’s right flank, Klenau’s Austrian IV Corps captured lightly defended Kolmberg Heights to the northeast of Liebertwolkwitz and on the left Prussian II Corps under Kleist fought its way into Markkleeberg, only to be thrown back by a determined French counterattack.

The Russian I Corps under Gorchakov attacked Liebertwolkwitz defended by Lauriston and the Russian II Corps under Prince Eugene of Wurttemberg attacked Wachau, defended by Victor. The fighting for Wachau was brutal. The destroyed village changed hands several times, but by the end of the day the French still possessed Wachau. Gorchakov’s columns, shattered by massed artillery fire from Lauriston’s corps, fell back. Doing so, they lost contact with Prince Eugene.

Napoleon moved reserves forward to support the front line. Augereau took up positions behind Poniatowski, Oudinot deployed behind Victor and Mortier behind Lauriston. Napoleon shifted the Old Guard and Murat’s three cavalry corps to a central position behind Markkleeberg and Liebertwolkwitz.

On the Allied left Merveldt’s Austrian II Corps splashed through the swampy ground between the Elster and the Pleisse heading for the French right flank at Connewitz and Dolitz with the aim of enveloping Markkleeberg. Merveldt’s lead elements captured a small chateau at Dolitz, but were stopped by Poniatowski.

At 10 a.m., just as Marmont began moving south, Blücher’s leading elements began engaging the French outposts. Ney immediately halted Marmont with orders to take up new positions at Mockern. Aware that Napoleon wanted troops shifted to the south, Ney dispatched Bertrand in Marmont’s place. As Bertrand began to move a half hour later, Gyulai’s corps attacked toward Lindenau. The Austrians drove in Arrighi’s cavalry pickets. Arrighi sent to Ney for help.

Ney responded by redirecting Bertrand over the causeway in time to repulse Gyulai’s advance on Lindenau. Next, Ney dispatched Souham’s understrength III Corps consisting of two of its three divisions, to the south. This left Ney only with Marmont’s corps and Dabrowski’s division in the north.

After three hours of fighting, the Allies still had not made any inroads anywhere. At that point, the momentum of the Allied attack began to wane. Barclay’s infantry could not advance in the face of punishing fire from French artillery and began to edge back. Seeing Allied pressure reduced, Napoleon judged the time right for a counterattack. He ordered the corps of Lauriston, Victor, and Augereau to fix Barclay from the front while two cavalry corps attacked the vulnerable Allied center. At the same time, MacDonald and Sebastiani would envelop the Allied right flank, keeping Barclay pinned against the marshy banks of the Pleisse River.

Seeing French columns begin to gather between Wachau and Liebertwolkwitz, Barclay brought up Rayevski’s Grenadier Corps and Alexander ordered the Russian and Prussian Guards to back up Rayevski. Meanwhile, Schwarzenberg received a request to send Austrian reinforcements to the right bank of the Pleisse. Pulling an Austrian division from the reserve, he sent it on its way.

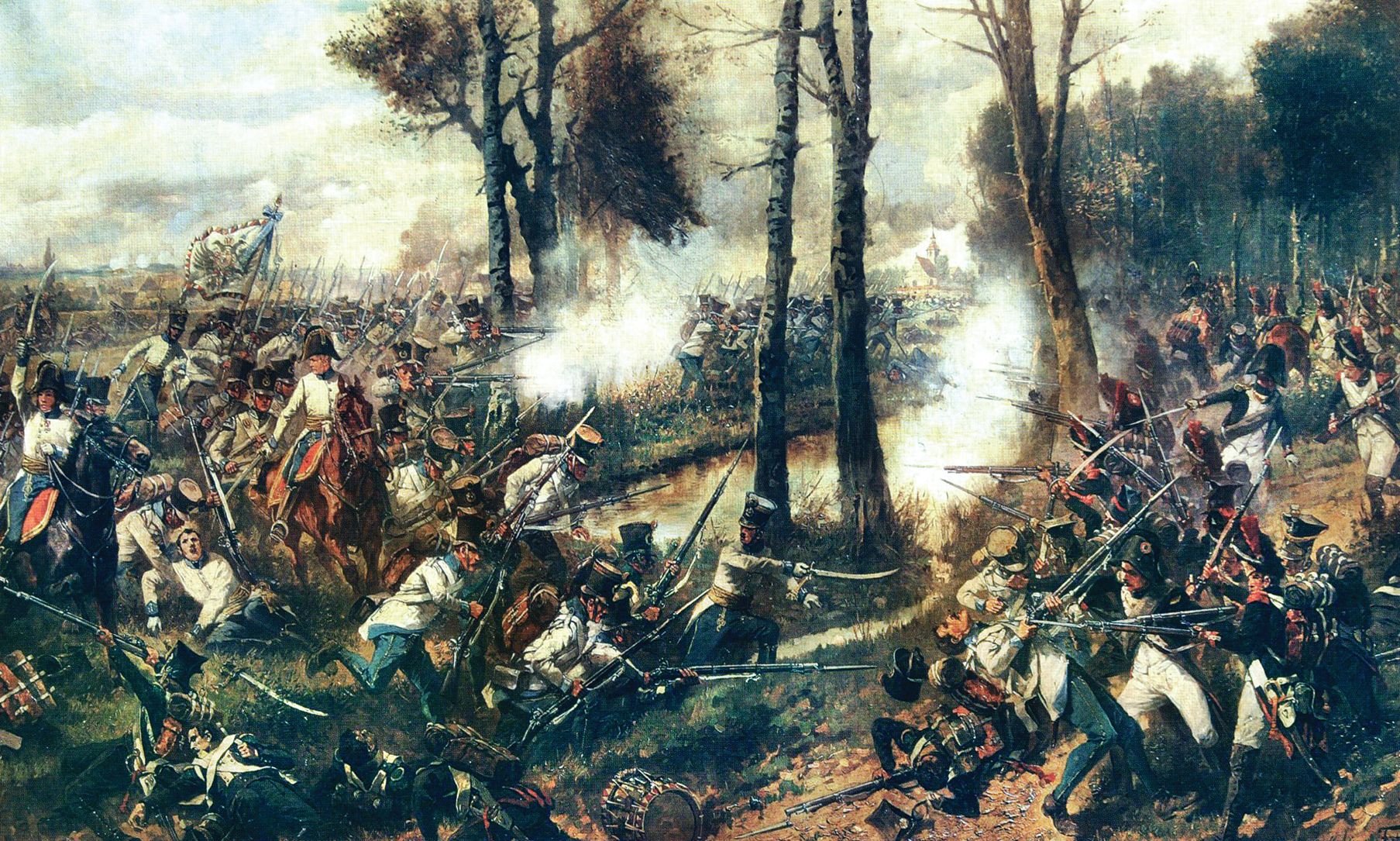

The French attack began at midday. After two hours, the unrelenting pounding from French artillery severely damaged the Allied front line. Especially serious casualties were in Prince Eugene of Wurttemberg’s Russian II Corps, where some battalions were reduced to company size. Under Murat’s orders Latour-Maubourg personally led forward General Etienne Bordesoulle’s heavy cavalry division. Leading the charge, six French and two Saxon cuirassier regiments punched a hole in Prince Eugene’s line. Sabering gunners as they cut a swath through the Austrian line, the French cuirassiers came dangerously close to Alexander’s command post.

All along the length of Barclay’s front line, the Russian and Prussian units fell back under heavy pressure. Following the I Cavalry Corps, French Guard Cavalry shattered Kleist’s corps. Only Rayevski’s grenadiers, formed into squares, held steady. Flowing around the Russian squares while taking volleys from all sides, Bordesoulle’s cuirassiers rode on. As they did so, they disordered the Russian Guard Light Cavalry which was just coming up and had not yet deployed for battle. The French seemed on the verge of victory. “The world still turns for us!” Napoleon shouted to his secretary Agathon Fain.

Barclay moved his heavy cavalry to plug the gap torn in his line by French cavalry. He brought up fast-moving horse artillery to bolster his position. After quickly coming on line, the guns opened a punishing fire on the French horsemen. With saddles emptying around him, a cannonball shattered Latour-Maubourg’s leg. “What are you crying about?” he remarked to his tearful valet when it had to be amputated. “You have one less boot to polish.”

Elsewhere on the battlefield, General Orlov-Denisov led the Life-Guard Cossack Regiment to relieve pressure on Guard Light Cavalry. The Guards rallied, and together with Russian and Prussian cavalry from the Allied reserve, pushed the French horsemen back.

At the same time heavy fighting wore on around Wachau with the French troops of Victor and Oudinot clashing with Rayevski’s spirited grenadiers. The fighting see-sawed back and forth in the village, but the French prevailed. On the far Allied right, the enveloping maneuver by three French corps (MacDonald XI Corps, Lauriston’s V Corps, and Sebastiani’s II Cavalry Corps) failed to dislodge Gorchakov and Klenau, who benefited from the timely support of Pahlen’s cavalry.

Austrian General Frederick Bianchi, who led two infantry and a cavalry corps, counterattacked the Allied left at 4 p.m. His troops flung back the French under Augereau and Victor, forcing them to withdraw behind Markkleeberg. The dangerous situation on the French right was salvaged by the arrival of a division of the Old Guard, followed by the arrival of one division from Souham’s III Corps. The fresh French troops drove back Bianchi’s troops. In addition, they ejected Merveldt’s troops from Dolitz and pushed them back across the Pleisse. In a reverse of Austrian arms, Merveldt was captured. After infantry and cavalry on both sides pulled back in the center, sporadic artillery exchange continued from maximum ranges before dying down.

While heavy fighting continued in the south, Blücher went into action in the north. Advancing at 2 p.m. from Schkeuditz, he intended to strike Marmont’s right flank. At the same time, General Ludwig Yorck’s I Prussian Corps began its advance on Mockern. A powerful force under Russian General Louis Alexander Langeron, composed of three Russian infantry and one cavalry corps, attacked Dabrowski’s Polish division at Wiederitzsch. Expecting additional French forces to arrive from the direction of Duben, Blücher left General Fabian Sacken’s Russian XI Corps in reserve.

At that point, Ney recalled one of the divisions of Souham’s III Corps that was moving toward Wachau and sent it back to support Marmont. Souham’s other division commanded by Delmas continued south where it eventually reached Dolitz in time to assist in repulsing Merveldt’s attack.

As Dabrowski was falling back under the weight of superior numbers, Delmas’ French division, the third division of Souham’s III Corps, appeared on the Duben road. In the mistaken belief that a large French force was advancing against him, Langeron halted his troops. This afforded Delmas an opportunity to get his troops across the Parthe River unopposed and continue toward Leipzig. Delmas, though, abandoned most of the wagons in the supply train that he was escorting.

Yorck’s I Prussian Corps held Mockern, which was situated 75 miles north of Leipzig. The Prussian general repeatedly attacked the positions of Marmont’s VI Corps. Prussian infantrymen reached the outskirts of the village several times. With fixed bayonets, they charged repeatedly against French soldiers defending the houses in the village. Eventually after three hours of heavy fighting, Yorck’s infantry fell back in disorder.

Ney ordered a Wurttemberg cavalry brigade to charge at 5 p.m., but the stubborn Wurttembergers refused. This forced Marmont to attack with only infantry. Yorck countered with a cavalry charge that compelled Marmont’s foot soldiers to call off their attack and retreat.

The Prussians soon captured Mockern. The approach of night prevented Sacken’s XI corps from exploiting the attack and Marmont rallied his corps south of the village, leaving Mockern in Prussian hands.

The Prussians, realizing they had considerable momentum, pitched into Dabrowski’s Poles and drove them back toward Eutritzsch. The Poles subsequently linked up with Marmont’s troops. Arrighi’s cavalry moved into position behind the Poles to support them. One of Souham’s divisions, which spent the day marching and countermarching around Leipzig, arrived too late to participate in the fighting. Both sides fighting in the northern sector suffered heavily, with Yorck’s corps bearing the brunt of fighting and casualties.

The Allies suffered 30,000 casualties at Leipzig, while the French lost 25,000 men. If Napoleon remained in position to fight a second day, he knew that his reinforcements consisted of just the 14,000 troops of Reynier’s VII Corps to bolster his strength, while the Allies expected significant reserves in the form of Bernadotte’s Army of the North, Bennigsen’s Army of Poland, and Colloredo’s Austrian I Corps.

Napoleon could not admit the possibility of defeat which meant giving up control of Germany and abandoning 100,000 French troops garrisoning fortresses on the Elbe, Oder, and Vistula rivers. While waiting for Reynier’s corps to arrive, Napoleon decided to send his high-ranking prisoner, Austrian General Merveldt, to Emperor Francis II with an offer of an armistice as a ploy to buy more time. Sensing Napoleon’s weakness, the Allied monarch ignored the offer.

There was little action on October 17. Blücher initially advanced against Marmont and Dabrowski, pushing them further, but halted after receiving word from Allied headquarters about the general offensive set for the next day.

Even the arrival of Reynier’s VII Corps did not make up for the French losses suffered the previous day. By that time in the battle, Napoleon could field no more than 165,000 men and 740 guns. The French emperor spent the day in inactivity, awaiting a response to his offer of armistice, which never came. Although he still believed he could beat the Allies, Napoleon took some precautions in case of retreat to the west. He ordered additional bridges built at Lindenau, but they were not completed in time. At the same time, Bertrand prepared to move toward Weissenfels to secure bridges over the Saale River at Weissenfels.

Pulling his forces closer to Leipzig during the night, Napoleon deployed them in a semicircle between the Pleisse and Parthe. The left flank was anchored on the Parthe at Schonefeld, and the right on the Pleisse at Connewitz. The key to the position was Probstheida located in the center. Napoleon left small forward detachments at Dolitz, Wachau, Liebertwolkwitz, and Holtzhousen to delay the anticipated Allied attack.

Bennigsen and Colloredo reached the battlefield that day and went into position on the extreme right of the Allied line. Bernadotte also arrived and deployed to the left of Blücher. As the fog began to dissipate at 7 a.m. on October 18, Allied guns opened fire all along the line, signaling the advance as Schwarzenberg, Barclay, and Bennigsen pushed their deep columns forward. The French forward detachments put up a spirited fight, but were slowly falling back to the main French line.

Barclay, deployed in the center, took Wachau and Liebertwolkwitz and after approaching Probstheida halted, waiting for Bennigsen to come up on line with him. Bennigsen, attempting to envelop the French left flank defended by MacDonald and Reynier, was held up for a time, before capturing Holzhausen and several nearby hamlets. On Bennigsen’s right flank, Platov’s Cossacks attacked two Wurttemberg cavalry regiments in front of them, both of which went over to the Russian side.

In the late morning, Bennigsen came up on the line with Barclay and the main battle began in earnest. On Barclay’s orders, Wittgenstein advanced against Probstheida, the key position in the center, defended by Victor and Lauriston. The village was flanked by 50 French guns on each side and the Old Guard was ready in reserve. Wittgenstein advanced in three lines, with Kleist’s Prussians leading the way, with Gorchakov and Prince Eugene’s Russians in support.

Weathering the storm of artillery fire, the Prussians broke into Probstheida. The French, however, drove them out. Gorchakov came up to support Kleist and together the Russians and Prussians fought into Probstheida again, only to be ejected by the counterattack of the Old Guard. Barclay halted waiting for developments in the north and on the left.

On the left, Austrian reserve corps under Prince Louis William of Hesse-Homburg crossed the Pleisse, captured Dolitz and continued against Poniatowski and Augereau at Connewitz. A timely counterattack by Oudinot’s Young Guard corps stopped the Austrian attack and temporarily retook Dolitz. Hesse-Homburg occupied Dolitz again, but was wounded by French fire while leading the attack. Command of his troops devolved to Colloredo. The French attack threatened the Allied left flank and Schwarzenberg ordered Gyulai to move from his position at Grunau, where he was watching Lindenau and the road to Weissenfels, to cross the Pleisse to support Colloredo.

With additional forces Schwarzenberg secured the left flank and ordered Gyulai, whose troops were still on their way, to turn around and return to Grunau. With Gyulai no longer blocking the road to the southeast, Bertrand moved through Markranstadt to Weissenfels to secure bridges over the Salle River. Two divisions of Young Guard took over Bertrand’s positions at Lindenau.

In the north, Blücher and Bernadotte advanced at 8 a.m. when cannon fire was already heard from the south. Driving on Mockau from the northwest, Blücher sent Yorck’s and Sacken’s corps against Dabrowski’s Polish division at Mockau. Even though severely outnumbered, the brave Poles, who were supported by Arrighi’s cavalry, fell back to the northern suburbs of Leipzig in good order. Nevertheless, the situation on their right flank at Schonefeld was growing increasingly desperate.

Langeron joined forces with Bernadotte with his three infantry and one cavalry corps and advanced on Mockau from the northeast. He forced a crossing over the Parthe at Mockau in the face of French guns and fought to the edge of Schonefeld, which was occupied by Marmont with Souham’s lone division in reserve. The French turned Schonefeld, with its stone houses and walls, into a formidable defensive position.

After the initial frontal attack was repelled, the Russians brought up artillery and commenced firing on the enemy at point-blank range. After scouring the stone walls with grapeshot and blasting the houses, the Russians broke into the village, only to be checked when Ney sent Souham to reinforce Marmont. Bernadotte reinforced Langeron with Russian and Swedish batteries and the British rocket battery under Captain Richard Bogue, the only British unit among the Allied armies. In an ensuing artillery duel, Bogue was killed. The fighting was brutal. The village changed hands several times, but by evening Schonefeld was in Langeron’s hands.

Screened by Langeron, Bernadotte finally made a slow crossing over the Parthe River at Taucha around noon. He stayed there until mid-afternoon when he finally began moving toward Leipzig on Langeron’s left. This move placed him in direct contact with Bennigsen on the extreme right flank of the Allied line. Allied forces had taken up positions on three sides of Leipzig. The only escape route from the city was through its western suburbs.

After a quick in-person meeting, Bernadotte sent Marshal Friedrich Wilhelm Freiherr von Bulow’s corps to support Bennigsen and they advanced together on Sellerhausen, an eastern suburb of Leipzig, defended by Reynier. As the Russian columns were forming up, a Saxon infantry division, along with a cavalry brigade and artillery, defected to the Allies, creating a gap in Reynier’s lines. The Saxons’ move to the Allies was so rapid that the French, believing that the Saxons were attacking, cheered them.

The defection of the Saxons left Reynier with half of this corps. Bennigsen and Bulow quickly rushed forward to exploit the gap. Ney sent Reynier a division pulled from fighting around Schonefeld. Napoleon rushed Nansouty’s cavalry corps to the threatened sector accompanied by Guard artillery. The emperor followed this force. Arriving at the threatened sector, Napoleon found the gap reoccupied by the division sent by Ney and Nansouty’s corps.

Preferring to let the Russians and Prussians do the bulk of fighting, Bernadotte held back his Swedish troops. Upon the insistence of his senior Swedish officers, Napoleon committed Marshal Curt von Stedingk’s Swedish corps to the fight at mid-afternoon. After heavy fighting, Bennigsen and Bulow took Sellerhausen just before nightfall.

Encroaching darkness put an end to the fighting. With his men exhausted and ammunition dwindling, Napoleon finally gave orders to retreat. Shortly after nightfall Napoleon sent the trains, artillery parks, and part of his cavalry over the Lindenau causeway. The Old Guard was to march next, followed by the Young Guard, then Augereau’s IX Corps and Victor’s II Corps, and lastly the three cavalry corps. Napoleon designated MacDonald’s, Poniatowski’s, and Reynier’s corps to serve as the rearguard. For his bravery and faithful service, Napoleon promoted Poniatowski to marshal, presenting him with the marshal’s baton on the battlefield.

Before dawn on October 19 the French began cautious withdrawal. Allied pickets reported the sounds of their movement, but it was not until two hours after sunrise that the Allied command realized that a full-scale French withdrawal was under way. By 10 a.m. the Allied forces renewed the attack on Leipzig.

The French rearguard corps began a fighting retreat, inching back under the weight of Allied numbers. The villages which were fought over the last three days were smoking ruins, all the environs were scattered with corpses and moaning wounded, dismantled cannons, horse carcasses, and dropped muskets. Jubilant Allied soldiers, who sensed that victory was near, broke into suburbs. They fought hand-to-hand, and house-to-house against the French infantry. Blücher’s troops in the north penetrated deep into the French positions moving rapidly along the east bank of the Elster.

With sounds of fighting intensifying behind them, French troops filed quickly through Leipzig. In their haste, they broke ranks. This created a substantial jam as troops tried to press their way through the only defile at Lindenau. Napoleon and his entourage crossed over to Lindenau at 11 a.m. amid increasing disorder, while Prussian King Frederick William III became trapped in Leipzig as ecstatic civilians poured into the streets.

Napoleon issued orders to Dulauloy of the Guard Artillery to destroy the bridge once the rearguard crossed over the structure. Dulauloy in turn delegated the task to a Colonel Montfort, who passed the responsibility down the line. The enormous task fell to one Corporal Lafontaine.

With their resistance collapsing at 1 p.m., French soldiers from the three rearguard corps began streaming over the Lindenau Bridge with Allied bayonets at their backs. Seeing the Allied soldiers in close pursuit, Lafontaine panicked and blew the bridge with French soldiers still on it. The destruction of the bridge trapped 20,000 French soldiers on the far side of the Elster. Hundreds of men flung themselves in the river in an attempt to swim across. Marshals Oudinot and Poniatowski attempted to swim the river by hanging on to their horses. Oudinot safely made it to the other bank, but Poniatowski, who was in a weakened state as a result of two wounds received in battle that day, drowned just 12 hours after receiving his marshal’s baton from the French emperor.

Napoleon led the remnants of his army west by forced marches. Demoralized by heavy casualties, exhaustion, and lack of food, the Grande Armée melted away through desertions and straggling. The Allied commanders decided not to pursue the retreating French units.

The Grande Armée suffered 43,000 killed and wounded and 38,000 captured. Additionally, 6,100 German troops defected during the battle. Among the French casualties were Polish Marshal Poniatowski and 11 generals killed or mortally wounded, 12 wounded generals, and 36 generals captured. Reynier and Lauriston were among those captured. The Allies also captured Frederick Augustus of Saxony and Prince Emil of Hesse-Darmstadt. The Allies took possession of 325 French cannons and most of Napoleon’s supply train. Allied losses amounted to 54,000 men. The Russians and Prussian suffered the bulk of casualties. The Swedes, carefully shepherded through the battle by Bernadotte, lost less than 200 men.

The Battle of Leipzig, known as the “Battle of Nations,” was one of the largest and most decisive battles of the Napoleonic and Revolutionary wars. With the loss at Leipzig, Napoleon’s rule east of the Rhine River came to an abrupt end on November 2. The defeated French emperor retreated across the Rhine into France. The Confederation of the Rhine soon collapsed. The Allies invaded France in January 1814, and Napoleon abdicated three months later. The end of the Napoleonic era drew near, but it was not over yet.

The Emperor of Austria was Francis I and not Francis II.