By Christopher Miskimon

Private Bruce Fenchel was writing a letter home when his first sergeant burst into the barracks room. “Pack your duffel bags and get ready to roll,” the NCO said ominously. “One man go to the kitchen and take any food you can get.” Their unit, D Company of the 8th Tank Battalion, part of the 4th Armored Division, was on their first break from the front lines after over 80 days of combat. Now that rest period seemed over just as it started. It was December 19, 1944.

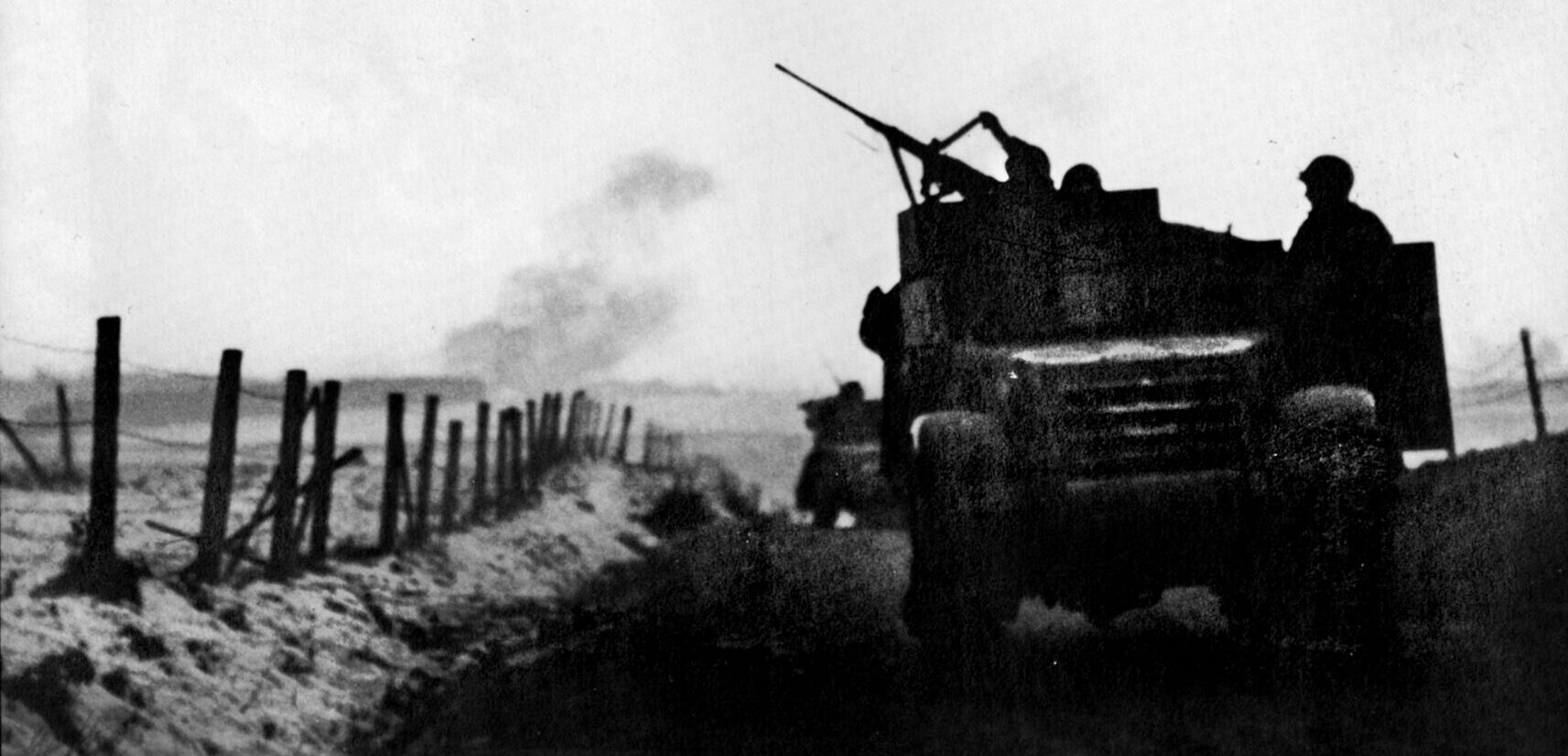

The soldiers of D Company let out a collective groan of disappointment and frustration, but the First Sergeant kept issuing instructions. “The rest of you put the machine guns back on your tanks and gas them and be ready to roll in two hours.” The company’s senior non-commissioned officer (NCO) went on to explain the German army had broken through American lines in the Ardennes, north of their current location. The 4th Armored Division, as part of General George Patton’s U.S. Third Army, would head north and tear into the enemy’s flank.

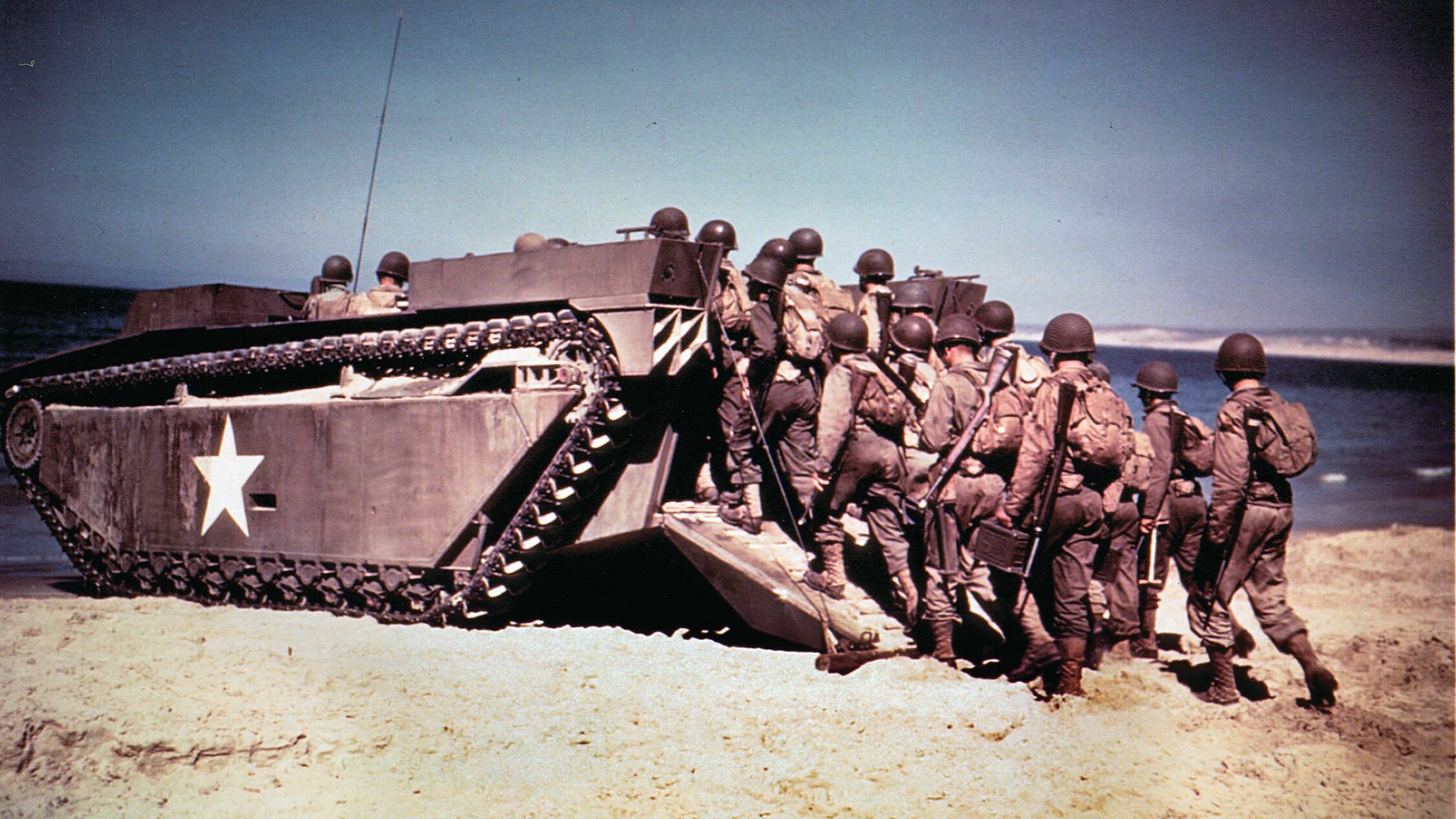

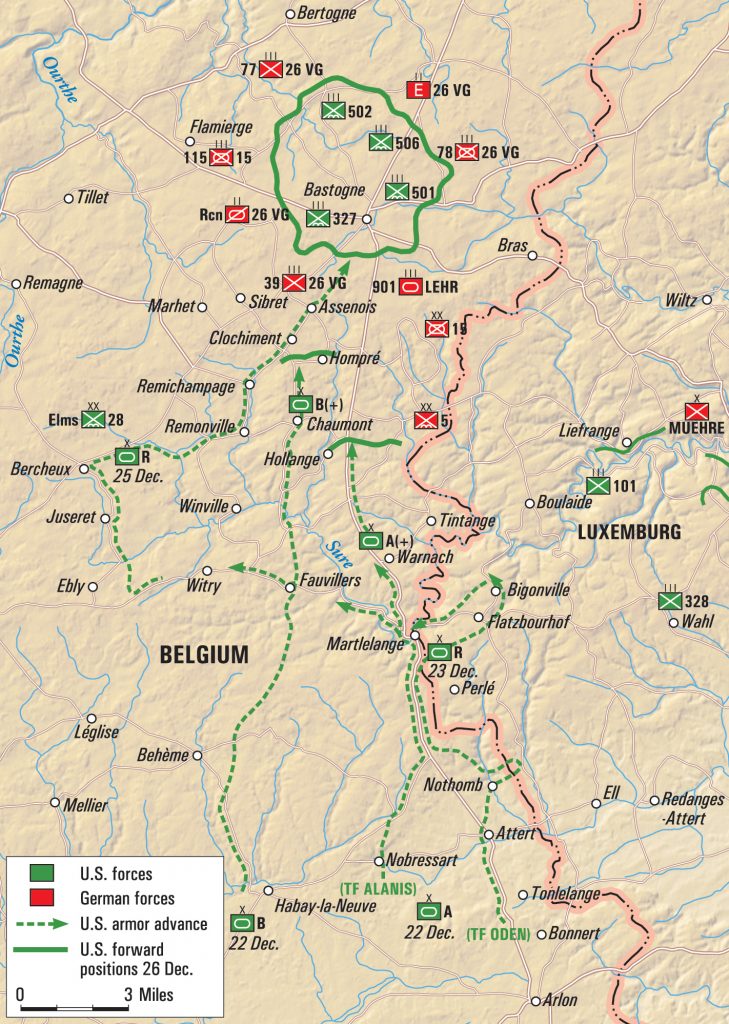

The battalion commander, Major Albin Irzyk, wasted no time getting his unit moving. The 8th Tank Battalion formed part of the division’s Combat Command B; each armored division divided its battalions into Combat Commands, designated A, B, and R (Reserve). Combat Command B (CCB) also contained an armored infantry battalion, a self-propelled artillery battalion, and supporting attachments of engineers, cavalry scouts, and tank destroyers. They left their temporary barracks in Lorraine, France, and set out for Belgium. The command’s orders were to reach Bastogne, where a mixed U.S. force of paratroopers from the 101st Airborne Division and elements of an armored combat command lay surrounded and besieged.

Three days later, Fenchel sat in the driver’s seat of his M5 Stuart light tank, part of a column of vehicles pushing ahead toward Bastogne. They had driven all night on December 22, eager to reach the surrounded Americans in time. Patton, always aggressive, pushed his men to keep moving, aware that hitting the Germans hard and fast was the best way to beat them. Irzyk ordered a platoon each of jeep-mounted cavalry and light tanks to lead the way, depending on their better mobility to keep the advance in motion. Fenchel’s tank platoon was chosen, and after refueling they kept going all night. Driving a tank at night was difficult; Fenchel once lost sight of the Stuart ahead of his until it suddenly appeared out of the darkness and he ran right into it. Luckily, there was no damage and the column got moving again.

The column had almost reached the village of Chaumont just as the sun appeared in the east, casting dim light across the frozen landscape. The Stuart crews pulled their tanks off the road for a brief maintenance check while the cavalrymen in the jeeps scouted ahead. Suddenly, gunfire erupted from both sides of the road. German paratroopers of the 5th Fallschirmjäger Division opened fire with machine guns and panzerfaust antitank weapons. From a distant ridge, Sturmgeschutz self-propelled assault guns sent high-velocity cannon shells screaming at the hapless cavalry platoon. Caught in a crossfire, two jeeps were soon aflame. Irzyk ordered the Stuarts to flush the German troops out of the tree line and keep the road clear. Most of the tanks were already fighting, their .30-caliber machine guns chattering as they moved across the fields toward the trees. The fight to reach Bastogne had begun.

The German Ardennes offensive caught the Allies by surprise, but they reacted swiftly. The sector was lightly defended by a combination of units either exhausted and understrength after fighting elsewhere or too green and inexperienced to be placed into heavy combat yet. The initial German attacks had mixed success; in some areas they punched through the thin American lines with relative ease. In other places, small ad hoc groups of GIs put up stiff resistance, causing delays the Germans could not afford. Hitler’s goal was to reach the port city of Antwerp, Belgium, driving a wedge between the American and French forces to the south and their British Commonwealth comrades to the north. The plan was futile; even if the panzer columns reached Antwerp, the idea that this would destroy the Anglo-American alliance was wishful thinking at best. As the German divisions pushed west, they formed a large salient in the American line; hence the operation’s more famous name, the Battle of the Bulge.

The attack had to be dealt with, and General Dwight Eisenhower, Supreme Allied Commander in Europe, saw this as an opportunity rather than a threat. Much of the Third Reich’s remaining combat power was now rampaging through the Ardennes, exactly where the Allies could cut it off and destroy it. General Patton’s Third Army was a key part of that response. Patton was an aggressive, offensive-minded leader with a reputation for bold action. His army was already preparing its own attack across the German border toward Frankfurt, scheduled for mid-December, when the Bulge fighting began on December 16, 1944.

With Patton’s army already well-supplied and prepared, it made sense to pivot his forces to the north and smash them into the Germans’ southern flank. It meant cancelling his own plans and moving over 100 miles, but Patton expressed confidence in his troops to Eisenhower and Bradley, commander of the US Twelfth Army Group; his GIs could get the job done. “But what the hell,” he remarked, “We’ll still be killing Krauts.”

Patton chose three divisions organized into the U.S. III Corps to advance side-by-side for the pivot north. The 80th Infantry Division fell in on the right (east) flank, with the 26th Infantry Division in the center. The left flank belonged to Major General Hugh Gaffey’s 4th Armored Division, and this included the route to Bastogne. The 4th Armored was one of Patton’s favorites due to its good performance and aggressive leadership. It often served as the spearhead for Third Army’s attacks, and now Patton expected it to lead the way to Bastogne. Though it was a daunting task, the 4th’s leaders intended to do just that. Normally the division advanced with its two main Combat Commands, A and B, leading with the Reserve Command (R) held back to supply replacements for exhausted units or to exploit breakthroughs. By December 19, the division was moving.

The main German unit standing in 4th Armored’s way was the 5th Fallschirmjäger Division, commanded by Oberst (Colonel) Ludwig Heilmann. His division had 16,000 troops organized into three infantry regiments (the 13th, 14th and 15th), supported by artillery, engineers, antitank and antiaircraft troops, and a mortar battalion. The German Command attached a brigade of Sturmgeschutz assault guns to increase the division’s firepower. Like many German divisions at this stage of the war, it contained large numbers of former Luftwaffe personnel with little infantry training, including many of the leaders. There were also shortages of heavy weapons, including cannon, and even the Sturmgeschutz “brigade” had only 20 assault guns, probably StuG III models with 75mm guns. The division also lacked enough transport vehicles and was rated of “limited fighting quality” due to all these shortfalls. However, there were a few veterans spread through the ranks to stiffen the troops, and they were in dug-in defensive positions, the best place to put new troops. The frigid weather and harsh conditions also favored the defense.

The initial plan for 4th Armored Division assigned Brigadier General Herbert Earnest’s Combat Command A (CCA) with the main effort, using the 35th Tank Battalion (Lt. Col. Delk Oden) and the 51st Armored Infantry Battalion (Major Dan Alanis) and supported by the 66th Armored Field Artillery Battalion. CCA would move to the town of Arlon and start its advance from there. There was a good road network leading north with only one town, Martelange, and several small villages along the route for the German to occupy for defense. There were also several forests noted on the maps. CCA was chosen for the main thrust largely because it had the most operational tanks in the division. The neighboring 26th Infantry Division guarded the flank to the east.

Brigadier General Holmes Dager’s CCB secured CCA’s western flank. The 8th Tank (Major Irzyk), 10th Armored Infantry (Major Harold Cohen) and 22nd Armored Field Artillery battalions fell under CCB. Their assigned road network was not as good, and several small towns and villages dotted the route. Combat Command Reserve (CCR), under Colonel Wendell Blanchard, contained the 37th Tank (Lt. Col. Creighton Abrams), 53rd Armored Infantry (Lt. Col. George Jacques), and 94th Armored Field Artillery battalions. Initially, CCR stayed in reserve as it normally would, but the difficult conditions as the attack went on forced the division to commit it fully to the battle. Though understrength and short over 20 M4 Shermans and four M5 Stuarts, CCR had the superb leadership of Lt. Col. Abrams, an aggressive and skilled officer.

Now, on December 22, the advance proceeded slowly. The weather worsened, with blizzards cutting visibility down to a few feet. Ironically, some of the division’s worst impediments were caused by American combat engineers. As they retreated before the German advance, the engineers had blown up bridges and cratered roads to slow the enemy down. Now, American tanks needed those same roads and bridges, and both combat commands often had to wait for their own attached engineers to repair them.

While the engineers worked, General Earnest’s CCA combined his two task forces so they could better advance along the available roads. Ahead of them, Able Troop of the 25th Cavalry Squadron scouted the route. Shortly before 11 am, they found German troops dug in near the village of Flatzbourhof, Luxembourg. Soon the cavalrymen were engaged in a heavy firefight as CCA made its way north, driving through hilly country to Martelange, where they ran into more of the German line. The Sauer River wound along the northern edge of the town, with several bridges spanning the water. The Americans had to take those bridges intact if they could. A and B companies, 51st Armored Infantry advanced into Martelange with two platoons of Shermans from Baker Company, 35th Tank Battalion. Other tanks occupied high ground southeast of the town to give fire support.

Some GIs rode in on tanks while others went in on foot. As the lead tanks reached the first intersection, it erupted into chaos. German machine gunners and riflemen opened fire, forcing the Americans from the backs of the tanks. Several panzerfaust antitank warheads flashed across the street as GIs scrambled for cover. Somehow, not a single American infantryman was even wounded, and every panzerfaust missed. Within moments the Americans recovered and returned fire. Rifle fire lashed at the Germans while tankers fired .30- and .50-caliber machine guns. The firing kept on, but neither side could gain the advantage; both armies fought stubbornly. The on-scene American commander, Major Alanis, realized they could not punch through, so one of his company commanders ordered a platoon of tanks to flank.

The 2nd Platoon of B Company, 35th Tank, moved out near dusk, with a platoon of infantry in tow. The German defenders missed them in the dark, and within minutes the Yanks arrived in the center of town at a large church. Several vehicles sat parked in the street; the tankers peppered them with machine-gun fire and pumped high-explosive 75mm rounds into the enemy defensive positions. The heavy firepower of the tanks quickly overwhelmed the Germans, placing most of Martelange in American hands. Unfortunately, another German line awaited them on the north side of the Sauer River, covering the bridges.

While CCA fought in Martelange, a few miles to the west CCB pushed toward Chaumont. Its scouts, the 3rd Platoon of B Troop, 25th Cavalry, pushed ahead through heavy snow, often barely able to see the road ahead, much less the enemy. Still, they kept searching. During the morning they found a small group of combat engineers from the 101st Airborne, cut off from their brothers in Bastogne. Private John DiBattista recalled, “Heavy beards. No helmets. They were so wet that the GI overcoats looked black.” The scouts directed these stragglers south toward the main column and continued their mission.

Just after noon, the scouts drove over a small ridge and found the Sauer River. The road led straight to the river, but only rubble remained of the bridge. About 10 German soldiers guarded the remains. The troopers radioed their report to CCB but were spotted minutes later. Germans on a hill to the east pelted them with small-arms fire. DiBattista dove for cover as bullets struck the snow all around. Another soldier called for a medic; their lieutenant was hit. Someone radioed another contact report, giving the location of the groups firing at them. With the enemy located, 3rd Platoon fell back. DiBattista and a few others took refuge in a small house, where a woman started cooking for them. As she worked, German shells began soaring over the home, fired by a newly arrived German self-propelled gun. She kept cooking as if nothing were happening. Suddenly, a Sherman tank appeared and knocked out the German vehicle with cannon fire.

The tank belonged to Major Irzyk’s 8th Tank Battalion. He realized the engineers needed time and cover to get a treadway bridge set up. The commander sent one platoon of tanks to the crossing site and another to a hill just southwest of it. Both platoons hammered at the Germans with their cannon, while Irzyk arranged a fire mission from his artillery. Three batteries responded, lashing the enemy’s hill with 105mm high-explosive rounds. About 20 minutes later, a radio report came in. The surviving Germans were running away, the artillerymen were told, “mission complete.”

German artillery fire crashed around the bridging site, but Irzyk sensed it was time to advance. He sent two platoons of infantry across the river to secure the far side. Observers spotted another platoon of Germans on another hill, and Irzyk called for more artillery. Three minutes later, 105 mm shells roared down onto the enemy. Immediately, the enemy artillery fire lessened; the Germans had lost their own spotters.

Technical Sergeant Roscoe V. Albertson added to the fire with his mortar when he spotted a nearby German machine-gun team. He carefully adjusted his weapon after each round even as enemy fire landed all around him. One of his rounds landed right on the machine-gun position, knocking it out. This proved too much for the rest of the German unit; 16 men stood up and surrendered to Albertson right away. He received a Silver Star for his coolness under fire.

As the engineers built their bridge and cleared a nearby minefield, Major Irzyk ordered fuel trucks up to top off every tank. Soon, they were ready to move out, with a new platoon of scouts to lead the way. The column advanced, and at first all was quiet. Nearing Chaumont, however, they ran into the German 14th Fallschirmjaeger Regiment’s 8th Company. Other units of the regiment dotted the area, some able to join the fight.

This was where Bruce Fenchel, driving his light M5 tank, ran into trouble. The enemy opened fire during a halt, and Bruce was outside the tank doing maintenance. When bullets began bouncing off the armor of his tank, “I managed to crawl into my driver’s seat with machine gun bullets ricocheting off my tank. All of a sudden I was being covered with blood,” he recalled. “I looked up and saw my tank commander … he was dead, because he had been shot in the face. Two of our crew never even got inside the tank.”

Armor-piercing shells slammed into the other tanks, so Fenchel decided to get out of his own vehicle. He stumbled behind his M5 for cover from machine-gun fire, but then a shell struck, passing completely through his tank and past Fenchel’s head. He moved away from the burning wreck just as an explosive round landed nearby, throwing him through the air and knocking him senseless. When he came to, Fenchel crawled into a ditch and waited until he saw a fuel truck retreating past him, the cab full of men. They let him jump onto the running boards and clung to him as they frantically drove away. After a time, his hands numb from the cold, he asked them to drop him at the next house they found. He knocked on the door, and the residents quickly pulled him inside, took him to the attic, and covered him in blankets. He hid there the rest of the day, hoping the Germans would not return.

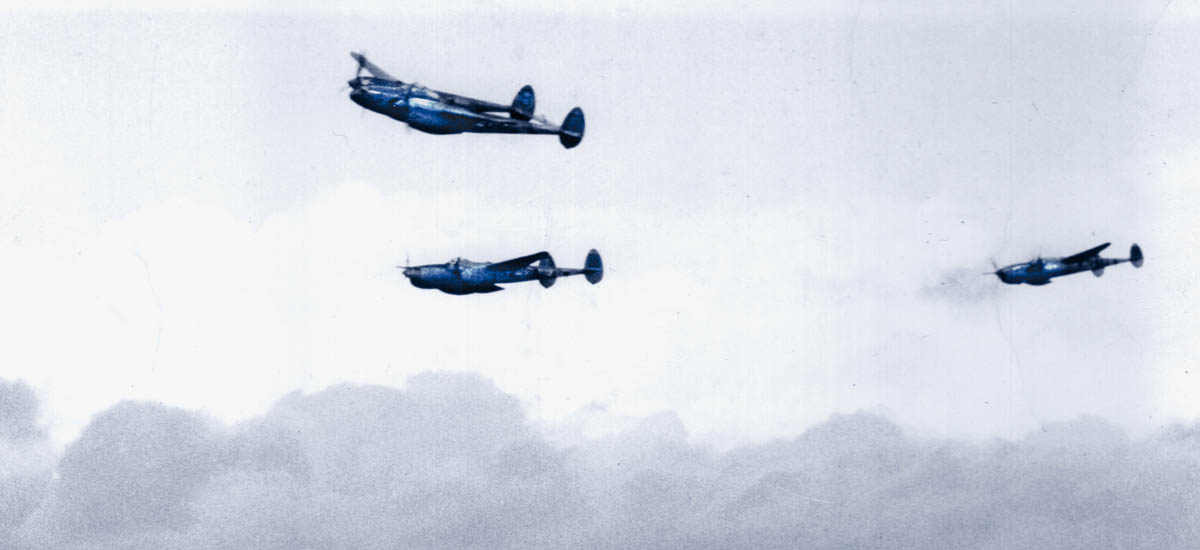

American artillery started pelting the Germans, allowing the American survivors to pull back. Major Irzyk decided to use all CCB to get the enemy out of Chaumont. Tank and infantry platoons combined into small task forces to occupy high ground outside the town and provide firing positions. Other tank-infantry groups attacked Chaumont directly, preceded by a bombardment using three battalions of artillery. The weather cleared enough for squadrons of P-47 Thunderbolt fighter bombers to strafe and bomb the town and several wooded areas occupied by the Germans. In return, enemy counterbattery fire struck the American artillerymen, and one battery was even strafed by a pair of German Messerschmitt Me-109 fighters.

Brutal fighting occurred within Chaumont. Tanks columns fired constantly to keep the Germans suppressed. The lead tank fired forward, the next tank to the left, the third to the right, and so on. German assault guns fired back until they were driven back by the heavy fire. Meanwhile, GI infantry started rooting the Germans out of each building. A machine-gun team stopped Staff Sgt. Lumpkin Glenn’s platoon, so he crawled up to the house and threw in several grenades; the enemy team fled. Outside Chaumont, screening U.S. cavalrymen saw a German force massing for a counterattack. The GIs opened fire, killing 40 enemy and destroying an anti-tank gun and a truck. By 4 pm, American tanks had reached the north end of town and hoped the battle was over.

Unfortunately, the fight was far from finished. Before the Americans could consolidate their gains, another German counterattack appeared, including several Tiger tanks and a few more assault guns. They took up unoccupied high ground north of town and pummeled the GIs of CCB with cannon fire. Several hundred German infantrymen attacked as well, pouring more fire on the shocked Americans. Irzyk and Major Cohen realized there was no time to form a coherent defense and ordered a retreat.

Even then, the soldiers of CCB fought bravely. Infantry NCO Charles Bennett ran through the enemy fire to rescue a wounded tank crew by jumping into their vehicle and driving it back to friendly lines. He earned a Silver Star for the act. Pfc James Carey made three trips in an abandoned German ambulance to get wounded men back to safety, receiving a Silver Star as well. A Distinguished Service Cross went to 1st Lt. Charles Gniot, who used a Browning Automatic Rifle to hold off the Germans while his platoon withdrew, but he did not survive to get his award.

Major Irzyk’s own tank crew fought as well, firing at the enemy tanks while Irzyk sat in the open commander’s hatch, instructing his driver to steer backwards because there was no room to turn around. Just as Irzyk thought they were safe, an 88mm round hit the tank. It ricocheted off the turret, knocked the crew around and left a hole in the armor the crew could see through. No one was seriously hurt, however, so they quickly got moving again.

The Americans pushed out of Chaumont and dug in on the south side of the town, but casualties were heavy. The battalion lost 11 tanks, including all of B Company’s. A and C Companies had only a platoon of tanks each, and the infantry had suffered 70 casualties. As the Americans dug in, their artillery once again pelted the Germans, who had no plans to advance further, content to hold the Americans at Chaumont.

CCR spent the first part of the attack in its usual place—in reserve—but intelligence reports indicated a possible German counterattack forming on the division’s right flank, where a gap appeared between them and the neighboring 26th Division. General Gaffey had little choice but to send in CCR to plug the hole in his line. A short radio call went out, and soon the 37th Tank Battalion’s recon platoon was on the move, followed by a tank company and armored infantry from the 53rd. The icy roads made for slow going, but soon they ran into the Germans outside the village of Flatzbourhof just before noon on December 23. German troops from the 15th Fallschirmjaeger Regiment dug in behind a railroad bed, and the surrounding woods put up heavy resistance.

Captain Jimmy Leach, leading B Company of the 37th, received a report of a German assault gun and a captured Sherman tank north of town. His artillery liaison, Captain Thomas J. Cooke, called in a Piper Cub spotter plane to watch for them. Leach put his three tank platoons to either side of the road leading into the village and advanced. First Platoon moved along the west side of the road. Staff Sgt. John Fitzpatrick led the platoon from the hatch of his Sherman, but a bullet struck him in the face, going through both cheeks and knocking out several teeth. He grimly stuck a bandage in his mouth to control the bleeding and kept going. Fitzpatrick realized most of the enemy fire came from a clump of trees to the northwest. He ordered Sergeant John Parks’ tank to advance on the trees while the rest of the platoon provided covering fire.

Parks pushed ahead, driving over the railroad embankment. When his tank got near the trees, Parks suddenly fell into his hatch. His gunner, Herman Coffy, checked Parks and found a bullet hole just over his right eye. With his leader dead, Coffy climbed into the commander’s hatch and took over. He ordered the driver, Russell Holland, to back the M4 over the embankment, but before they reached cover a German assault gun hit them and the tank burst into flame. Coffy and Holland got out, but Private Edward Clark did not. Captain Leach spotted the enemy vehicle from his own tank. He urged his driver forward, using the embankment as cover.

Once in position, Leach’s tank was “hull-down,” meaning only the turret lay exposed to enemy fire. His gunner, Corporal John Yaremchuk, first took aim at the captured Sherman. The first round went low. Loader Kenneth Jeffries pushed another round into the breech as Leach moved the tank a little further. That round also went low. They moved up again, and the third round crashed into the captured Sherman, which exploded in a ball of flame. Now having the range, Yaremchuk blasted two StuG assault guns behind the Sherman.

Next, the American artillery joined in, sending hundreds of 105mm high-explosive rounds into the woods. The barrage sent the enemy infantry running, some of them fleeing into Flatzbourhof and other going north. Infantry from the 53rd went into the woods to clean up while the tanks started to push into town. Second Lt. John Whitehill led A Company through Captain Leach’s line and toward town. The attack stalled, however, when Whitehill’s tank hit a mine, blowing off the left track. He got into another tank and continued, soon getting over the railroad. Whitehill saw some Germans moving into a house, but before he could act three rounds crashed into this tank. None of them penetrated, but two crewmen suffered injuries. Whitehill had to drive the tank back to the rear while 2nd Lt. Robert Gilson took command. Within minutes Gilson’s tank was hit and Gilson wounded, so Whitehill returned, climbed onto the back of a Sherman, and led his company from there.

Company C took over the attack, but within minutes its own commander, Captain Charles Trover, died by a sniper’s bullet. Lt. Col. Abrams called off the attack; the Americans would remain at Flatzbourhof for the night and advance on the next village, Bigonville, in the morning.

CCA found the Germans at Warnach in the late afternoon on December 23. The initial firefights led to general fighting when a group of American infantry in halftracks approached the town. Anti-tank guns destroyed two halftracks before falling to six American assault guns with 105mm howitzers. A patrol of M5 light tanks moved into town with artillery firing over their heads to cover them. They continued after dark, where two tank crews made a fateful mistake: They fired high-explosive and tracer rounds into some haystacks to provide light; one haystack exploded as if ammunition were hidden inside it.

Unfortunately, the flames gave German gunners light as well, and within seconds both Stuarts were hit. Edward Rapp, a gunner in one of the tanks, bailed out and took cover. Suddenly, he realized the turret was blocking the hatches of the crewmen in the hull. He ran back to the tank and traversed his turret so they could escape. All of them took cover near some GIs setting up a machine gun. Despite the heavy fire, Rapp watched an infantryman climb aboard his tank and use its turret-mounted .30-caliber machine gun to fire on Germans fighting from nearby houses. Tracers flashed all around the man as he calmly returned fire, suppressing the enemy. Thanks to him, several Americans caught in the open got to safety.

Soon Sherman tanks arrived at Warnach and joined the fighting. Pfc Robert Riley served as a gunner in Baker Company, 35th Tank Battalion. Approaching in the dark, his tank commander, Sergeant John Foster, asked permission to fire a white phosphorus round for illumination. This time the risk paid off. Riley lit another haystack on fire, revealing two enemy assault guns. Riley’s loader slammed a round into the breech just as the enemy vehicles moved to attack. He fired at the same moment as one of the StuGs; both rounds hit. The round hit the Sherman in the engine, starting a fire. The crew bailed out and ran for cover. Nearby, more StuGs dueled with Shermans. One well-hidden assault gun waited until a Sherman crew fired at an abandoned German vehicle and then hit the American tank before the crew could reload. The German crew did not see two other Shermans nearby; those tanks put several rounds into the assault gun, destroying it.

The destruction of the StuGs broke the morale of the German defenders in the area. They began running away, with American infantry shooting many down as they fled. Afterward, the GIs went from house to house, clearing them with grenades and submachine guns. Tankers supported them with cannon and machine guns. By late afternoon on December 24, Warnach belonged to CCA. A counterattack developed northeast of town, but concentrated American artillery stopped it cold.

Christmas Eve proved equally busy for CCR attacking Bigonville. Artillery pounded the defenses just before the American assault. Panzerfausts and mortars greeted A Company’s tanks as they reached the village. Meanwhile, two platoons from Captain Leach’s company forced their way into Bigonville, suppressing the enemy with machine-gun fire into every building they passed. As Leach’s tanks pushed their way through the town, Lt. Col. Abrams urged Leach to push even harder. Leach in turn yelled at the infantry to keep clearing buildings. As he shouted encouragement from his tank’s hatch, a bullet struck his helmet, slicing the sweatband inside and knocking him out. He awoke seconds later, got back up in his hatch, and kept giving orders.

Soon B Company pushed through to the north end of Bigonville to encircle the defenders. Small groups of German troops broke out; one group of 20 men simply ran between two Shermans and into a gulley before the tankers could bring their weapons to bear. The fighting remained difficult. Lieutenant Whitehill of A Company recalled the GI infantrymen, exhausted and understrength, becoming hard to move. Machine-gun nests in the houses held them up. At Abrams’ suggestion, Whitehill’s tanks switched to concrete-piercing fuses on their high-explosive shells. Designed to penetrate concrete bunker walls before exploding, they made short work of several machine-gun nests.

The Germans still resisted. Whitehill later wrote, “…a sniper was firing at me as I stood in the turret. His shells were flaking paint from the turret in my eyes as I peered out of the open hatch.” Trying to save cannon ammunition, Whitehill returned fire with his submachine gun, but a round struck him in the hand. That convinced the lieutenant to use a round of 75mm high-explosive, which ended the sniper’s career and cleared the street. The infantry started moving again, and soon the Americans made progress.

In the afternoon, a group of Germans tried to knock out the tanks supporting the American infantry as they methodically cleared houses. A panzerfaust struck one Sherman but caused no real damage. As the GIs tried to root the Germans out of each house, the tank crews tried a new tactic. They used a cannon round to blow a hole in each home’s wall and then sprayed the interior with .50-caliber machine gun bullets, followed by another 75mm shell. Not long afterward, white flags appeared as the surviving Germans surrendered.

As CCR secured Bigonville, General Gaffey issued orders changing their mission. CCB experienced strong counterattacks from the west, so the division commander decided to send CCR to guard CCB’s western (left) flank. The neighboring 26th Division would take over the Bigonville area. At the same time two battalions from the 80th Division’s 318th Infantry Regiment were attached to 4th Armored to replace their heavy casualties in infantrymen. The move occurred overnight from Christmas Eve to Christmas Day.

While CCR moved west, CCA began its next move, an attack on the village of Tintange, a mile south of the Luxembourg border and 7.5 miles south of the Bastogne perimeter. General Earnest sent in the 1st Battalion, 318th Infantry and his own 51st Armored Infantry, reinforced with combat engineers and tank destroyers. The tanks of 35th Tank Battalion stayed in reserve to reinforce wherever a breakthrough occurred. Tintange sat atop a hill with a valley to the south. The Americans had to cross that valley under fire. The men of the 318th advanced before dawn, hoping for concealment from the Germans, but they were discovered and fired on with mortars and small arms.

In places, the valley was so steep the Germans simply rolled grenades down onto the GIs. Casualties mounted as heavy fire pinned them down. One squad leader, Staff Sgt. William Murphy, spotted one of the enemy machine-gun nests and took a grenade off his belt. Pulling the pin, he charged the German position. Just as he threw the grenade, a bullet killed him, and he dropped to the snow-covered ground. The grenade landed on target, however, and knocked out the nest. This selfless act of courage resulted in a posthumous Silver Star. Nearby, 2nd Lt. George Kane got up and advanced toward the enemy. Two platoons of GIs followed his brave example, and soon they reached their initial objective. He also earned a Silver Star, but luckily lived to receive it.

Company B, 318th, waited in reserve during the initial advance. Seeing the situation, the company commander, Captain Reid McAllister, asked permission to join the attack. This was granted, and his understrength company of 58 men moved out. They immediately took casualties as well and were soon pinned down. Luckily, help arrived from several sources. Some tanks moved up to lend fire support. Overhead, a flight of eight P-47s appeared and dropped bombs and rockets on Tintange before strafing with their .50-caliber machine guns. As the pilots withdrew, they saw the American infantry below, advancing to the outskirts of town. This was followed by a two-hour artillery barrage before the GIs moved in to clear out the survivors. Tintange now belonged to the U.S. Army, but patrols sent toward the next objective, Hollange, met heavy resistance. With dusk approaching, that next village would have to wait until morning.

, CCB still struggled to take Chaumont. Second Battalion, 318th Infantry joined in for the push to reclaim the town. Major Irzyk assigned them to clear the woods south of Chaumont so the rest of CCB could push forward into the settlement. After taking the town, they would advance to the high ground to the north to prevent the Germans from making another counterattack from there.

In Chaumont, Bruce Fenchel still hid inside the attic of a civilian home. German troops entered the house, and Bruce listened as they questioned the family and sang Christmas songs. Eventually they left, and the family brought Bruce downstairs and ate a Christmas Eve dinner with him. Afterward, they played cards until Christmas morning, when Fenchel returned to the attic.

On Christmas morning the German received unenviable gifts: American artillery and air strikes. First, the 318th’s infantry advanced through the woods, clearing them in a few hours of intense fighting. Their battalion commander later said, “It was difficult to oust the paratroopers out of their foxholes and many were bayoneted while still in them.” Irzyk sent two platoons of light tanks in support, and by 10:30 am the woods were in American hands. As the rest of CCB started advancing, Irzyk called down the artillery. For 20 minutes, three dozen howitzers rained hundreds of shells on Chaumont, battering the Germans but not breaking them.

The 318th infantry tried crossing a field into the town but were stopped by heavy machine-gun fire. Again, individual soldiers made the difference. Sergeant John McNiff spotted a path leading to an enemy machine gun. He crawled along it until getting close enough to throw a grenade. Just after it exploded, he emptied his M1 rifle into the gun crew. Two died, and the other two surrendered. Nearby, Sergeant Celestino Lucero found another German machine gun. Telling his squad to stay still, he also crawled to the enemy nest and silenced it with grenades. Both men received the Silver Star. After recovering from an artillery burst that left him senseless, Pfc William South crawled 100 yards to flank a German position and spray it with fire from his BAR. He killed two Germans and captured four, earning a Bronze Star.

Pfc Roscoe Putnam found a German MG42 machine gun firing from a barn 150 yards away. As bullets tore into his comrades, he sprinted toward the structure. After 25 yards the Germans turned their gun toward him, so he crumpled to the ground as though shot. The trick worked, and the Germans pivoted their weapon toward other GIs. Putnam got up and ran the rest of the way to the barn, tossed in two grenades, and burst in firing his rifle. None of the Germans inside were killed, but they all surrendered.

The 318th’s bravery allowed the rest of CCB to get into Chaumont. GIs cleared the houses, supported by tanks. The 8th Tank battalion recovered seven Shermans lost during the earlier counterattack. From his attic perch, Bruce Fenchel saw the American tanks enter the town and ran down into the street. The first tank he saw was an M5 Stuart, driven by the gunner of his old tank. Fenchel told the man he wanted to go home. The gunner replied, “I’m going up in the turret of this tank and you’re getting into the driver’s seat.” Chaumont was captured, and Fenchel was back in the war.

After moving to CCB’s left flank, CCR pushed hard against the Germans. As the tanks pushed through each village, infantry was detached to clear it. Bastogne lay only a few miles away, and Abrams wanted his armor to reach it. Now the Americans were running into German units surrounding Bastogne, giving their enemy the difficult task of defending from two directions. Tank and infantry companies rotated through the lead position; one even used a bulldozer to push a stone fence into a crater in a small bridge, allowing them to maintain the advance. Dangerously close artillery fire landed just ahead of the lead tanks to keep the Germans suppressed.

At the village of Remoiville, some Germans chose to fight to the death, so the GIs obliged them with grenades and flamethrowers. Within a few hours the surviving Germans surrendered. The next morning, December 26, Abrams resumed the advance, hitting the town of Remichampagne. Captain Leach’s B Company pelted the town with cannon fire until the German occupants fled into some nearby woods. A flight of P-47s appeared and doused the woods in bombs, rockets, and napalm. Some infantry cleared the town while the tanks pushed on.

More P-47s arrived to hit anti-tank guns spotted at the next village, Clochimont. Even Abrams joined the battle, ordering his tank, named “Thunderbolt VI,” forward to engage a self-propelled gun. At 1,000 yards, his gunner destroyed it with a single shot. Captain Leach said, “I recommended him for the DSC right there. After all here’s the Colonel—a lot of colonels stay back at the goddamn flagpole but not Abrams. So he knocked that gun out.”

The final village on the way to Bastogne was Assenois. CCR was so close they watched a supply drop by C-47s over the besieged town. Company C, 37th Tank Battalion, took the lead with nine tanks, commanded by Lieutenant Charles Boggess. He took over the lead tank, an up-armored M4A3E2 “Jumbo” Sherman named “Cobra King.” Everyone was to follow him and drive for Bastogne. Artillery would cover their flanks, and other tanks and halftracks would follow.

The column sprayed gunfire ahead, left and right as it moved at full speed. Other tanks followed, firing into the woods to protect C Company. As Boggess reached Assenois, the artillery barrage started, hammering the German anti-tank and artillery crews and preventing them from firing at the Americans. Company C was almost through the town when a few Allied artillery rounds landed short, causing casualties and stopping part of the column. A few intrepid Germans ran onto the road and laid some mines in the gap. Boggess and three tanks kept going.

Soon they found a pillbox, and Boggess told his gunner to put some rounds into it. After destroying it, “I saw the enemy in confusion on both sides of the road. Obviously, they were surprised … some were standing in a chow line. They fell like dominoes,” Boggess wrote. Next, they passed a small field littered with parachutes from the recent supply drop. Now near the American lines around Bastogne, they slowed down.

“We cautiously approached a line of foxholes … out of each hole, a machine gun was leveled at my tank.” Boggess knew the Germans were using captured American vehicles and uniforms, so he shouted, “Come on out, this is the 4th Armored.” The GIs stayed in their holes. Boggess kept calling out until an officer came out of his foxhole and approached. He reached up a hand, and with a smile said, “I’m Lt. Webster of the 326th Engineers, 101st Airborne Division. Glad to see you.” Boggess took the offered hand, satisfied his company was the one that broke the siege of Bastogne.

Hours of fighting remained while CCR secured the route and cleared out the last German defenders. Several GIs ran onto the road under fire and cleared it of the German mines, allowing the column to continue. German counterattacks tried to close the narrow opening into Bastogne, but none succeeded. It took over a month of hard fighting, but the Battle of the Bulge ended in German defeat, inflicting losses the Reich couldn’t afford. But for the moment, CCR and 4th Armored were happy; they had achieved their objective.

Returning to Bastogne in 1984, Charles Boggess told a reporter, “I believe it is appointed to each man to have a few minutes of glory in his life. Mine lasted four miles and 25 minutes.”

Author Christopher Miskimon is a regular contributor to WWII History. He writes the regular books column and is an officer in the Colorado National Guard’s 157th Regiment.