By Mike Phifer

For weeks, Maj. Gen. William Rosecrans had been hearing increased grumblings from Washington about how he should move his army out of Nashville and strike General Braxton Bragg’s Confederate forces 30 miles away in Murfreesboro. So far, however, Rosecrans had failed to budge, and he gave no intention of doing so until he was good and ready. Newly appointed to his command in late October 1862, Rosecrans had replaced Maj. Gen. Don Carlos Buell, whom President Abraham Lincoln had sacked for his perceived poor handling of the just-concluded Kentucky campaign. Unlike Buell, who was not well liked by his men, the cigar-chomping, energetic, and optimistic Rosecrans was popular with both his officers and soldiers. “We were glad to be delivered of Buell,” wrote one sergeant in the 51st Indiana Regiment. “However good a military man General Buell may have been,” added Robert Stewart of the 15th Ohio, “he never won the love, and entirely lost the confidence of the army he commanded.”

Taking Command of the Army of the Cumberland

A West Point graduate and a devout Catholic, Rosecrans had enjoyed a relatively successful military career thus far in the war, having commanded Union forces in western Virginia and later served under Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant during the successful Corinth campaign. Taking command on October 30, Rosecrans found the Army of the Cumberland in a bad state. Thousands had deserted, troops had not been paid in six months, and supply lines were in constant jeopardy from fearless Confederate raiders such as John Hunt Morgan and Nathan Bedford Forrest. Rosecrans quickly moved his army from Bowling Green, Kentucky, to Nashville to counter a rumored Confederate threat against the Tennessee capital. At Nashville, he began to reshape the army, enforcing discipline and regulating camp life, which in turn led to an improvement in morale. “You don’t know how pleased everybody is at the change of Buell for him,” wrote Colonel Hans Christian Heg of the 15th Wisconsin. “I have just been up to Rosecrans’s headquarters and had a shake of the old fellow’s hand.”

Getting supplies into Nashville remained a problem. The Cumberland River was too shallow for navigation, and the Louisville & Nashville Railroad was being regularly ripped up by Confederate raiders. Rosecrans would not move until his supply problems were brought under control, even when he was threatened with removal. “The President is very impatient at your long stay in Nashville,” warned General-in-Chief Henry Halleck on December 4. “The favorable season for your campaign will soon be over. You give Bragg time to supply himself by plundering country your army should have occupied. If you remain one more week at Nashville, I cannot prevent your removal.”

For the time being, neither the Army of the Cumberland nor Rosecrans went anywhere. A defiant Rosecrans fired back to Halleck: “I need no other stimulus to make me do my duty than the knowledge of what it is. To threats of removal or the like I must be permitted to say that I am insensible.” Halleck toned down his rhetoric, but he continued to urge Rosecrans to act by informing him of the president’s concern for both Middle Tennessee and the reconvening of the British parliament, where it was feared that southern sympathizers would prod the government into recognizing Confederate independence. “Should the enemy be left in possession of Middle Tennessee,” wrote Halleck, “it will be said that they have gained on us.”

“Fight them! Fight, I say!”

By Christmas, with the Cumberland River rising, the railroad reopened, and five weeks’ worth of supplies built up at Nashville, Rosecrans at last was ready to move. It seemed an opportune time to strike—reports indicated that a division from the Army of Tennessee had been dispatched elsewhere and the bulk of the Confederate cavalry under Morgan and Forrest was off raiding in western Tennessee. Meeting with his corps commanders on Christmas Day, Rosecrans spelled out his marching orders for the army. Slamming down his mug of toddy on the wooden tabletop, Rosecrans exclaimed: “We move tomorrow, gentlemen! We shall begin to skirmish, probably as soon as we pass the outposts. Press them hard! Drive them out of their nests! Make them fight or run! Strike hard and fast! Give them no rest! Fight them! Fight them! Fight, I say!”

Thirty miles southeast of Nashville, the Confederate Army of Tennessee occupied a crescent-shaped defensive position, with the town of Murfreesboro in the center. From there, the Confederates could watch Rosecrans at Nashville and defend Middle Tennessee at the same time. When the bulk of weary Confederate soldiers had reached Murfreesboro in late November, they were in desperate need of rest and provisions. Desertion and disease haunted the army after Bragg led them in retreat from the unsuccessful Kentucky campaign. At Murfreesboro, much-needed food, clothing, and ammunition began to restore the soldiers’ health and confidence. Log cabins and snug shelters were built as the army settled in for the winter. Along with the approaching holidays, the gala wedding of John Hunt Morgan brought a festive spirit to the camp. Visits from family members of many Tennessee and Kentucky soldiers lifted spirits as well. “We lived like lords,” Gervis Grainger of the 6th Kentucky Infantry would recall.

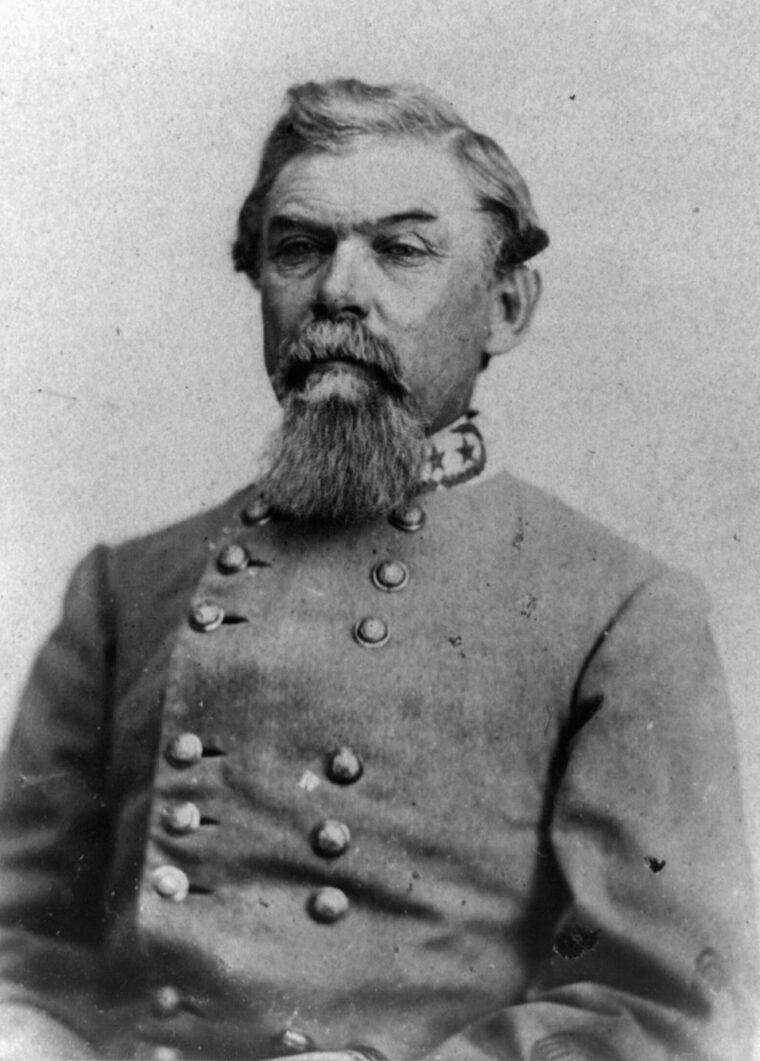

Not all was well, however. Two soldiers were executed for desertion, increasing the bitterness burning in the men against their stolid, dour commander. Braxton Bragg, himself a graduate of West Point and a decorated veteran of the Mexican War, was intensely disliked by the bulk of his men and officers. Often hampered by illness—real or imagined—Bragg was a strict disciplinarian who excelled at administrative duties, but he lacked ability as a battlefield tactician. In mid-December, Confederate President Jefferson Davis arrived at Murfreesboro to inspire the army, review the troops, and confer with his old friend Bragg, who had visited him a month earlier to discuss the calls for his removal. Bragg defended his conduct of the Kentucky campaign, where he had lost the Battle of Perryville to the since-deposed Buell. After the Richmond conference, Davis had placed General Joseph E. Johnston in overall command of the western theater, which would encompass Bragg’s command as well as that of Lt. Gen. John Pemberton in Mississippi.

Concerned over the defense of Vicksburg and the Mississippi River valley, Davis, despite Johnston’s earlier suggestion that troops be sent from Arkansas, weakened Bragg’s army by ordering 7,500 troops under Maj. Gen. Carter Stevenson to join Pemberton. Bragg opposed the move, assuring Davis that Forrest’s cavalry raids in western Tennessee would do more to slow down the Federal advance on Vicksburg than sending away part of his army with a large Federal force sitting only 30 miles away in Nashville. Davis, however, was insistent, not believing that Rosecrans would stir from Nashville before next spring at the earliest. If he did, Davis told Bragg somewhat unhelpfully, “Fight if you can and fall back beyond the Tennessee.”

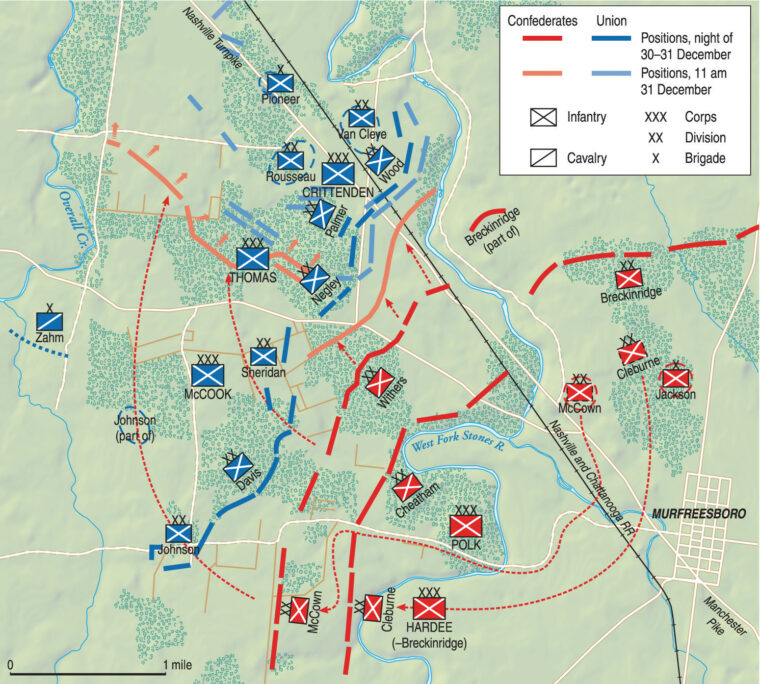

Skirmish on the First Day

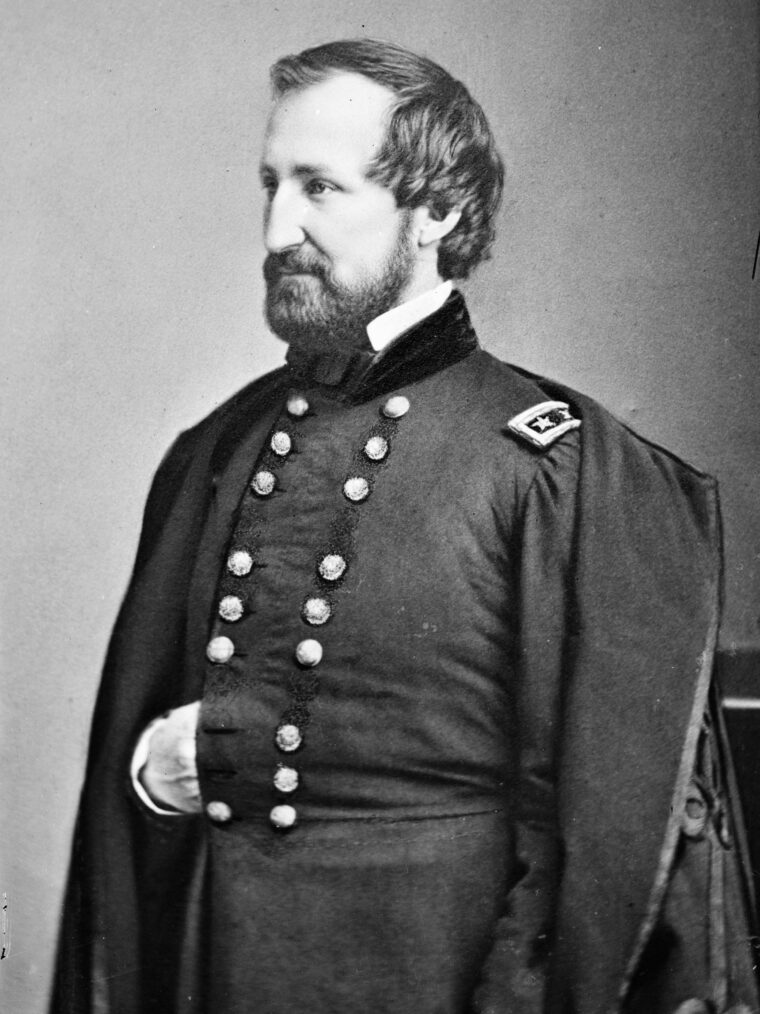

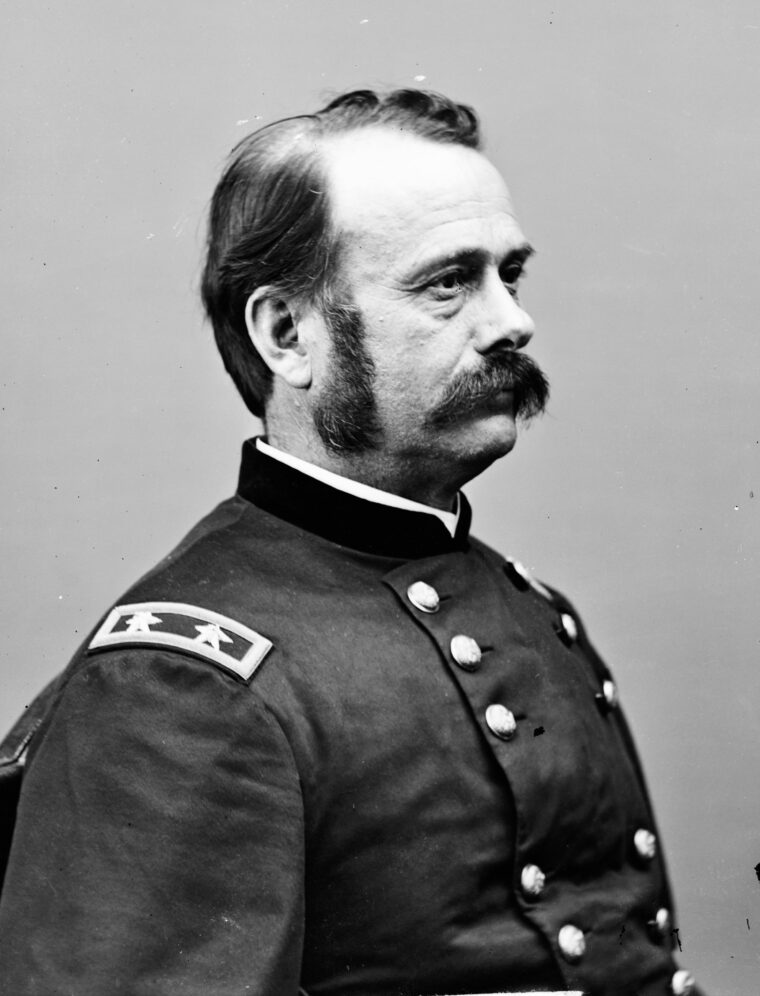

Rosecrans soon proved Davis wrong, although his advance got off to an inauspicious start. A cold, dreary day greeted the Army of the Cumberland as it marched out of Nashville on December 26. Rosecrans had divided the army into three corps. The right wing of the army, consisting of around 16,000 men, was commanded by Maj. Gen. Alexander McDowell McCook. He was to move due south down the Nolensville Pike. The 13,500-man center corps, under the command of Maj. Gen. George Thomas, was to proceed down the Franklin Road to Brentwood, then cut east behind McCook and take up position in the center of the army. The 14,500 men in the left wing, commanded by Maj. Gen. Thomas Crittenden, would advance along the Nashville-Murfreesboro Turnpike.

With the three columns well positioned to support each other if needed, the bluecoats trudged south down muddy roads while being pelted by driving rain. Union cavalry commander Brig. Gen. David Stanley had divided his command into three screening forces to accompany the infantry columns. Skirmishing quickly broke out as the Federal columns bumped into Confederate cavalry. Brig. Gen. John Wharton’s gray-clad troopers fought a delaying action against McCook’s column. Farther east, Confederate troopers under the command of Brig. Gen. Joseph Wheeler, who commanded Bragg’s cavalry, slowed down the advance of Crittenden’s men. Nightfall brought an end to the first day’s sparring.

The Federal columns were back on the move the following day. Confederate cavalry again fought a rearguard action to slow the Union advance and give Bragg time to concentrate his exposed forces. The 28th saw the Army of Tennessee move into position to meet Rosecrans’s advance, which had halted for the Sabbath to allow the weary soldiers to rest. Bragg had divided his 38,000-man army into two corps. The left wing was under the command of Lt. Gen. Leonidas Polk, a West Pointer who years earlier had resigned from the army to become an Episcopal bishop. Polk was critical of Bragg’s leadership and had said as much to Jefferson Davis when he visited the president after the Kentucky campaign, and he urged Davis to replace Bragg with Johnston. Polk’s corps was positioned west of Murfreesboro, separated from the town by the meandering Stones River, which was at his back. Maj. Gen. Jones Withers’s division was in the front line of Polk’s position, with Maj. Gen. Benjamin Franklin Cheatham’s division 500 yards behind him in reserve.

Hardee’s Rifle and Light Infantry Tactics

Across the river was Lt. Gen. William Hardee’s corps, the right wing of the Army of Tennessee. Hardee, another West Pointer, had seen action in the Seminole and Mexican Wars and had authored the famous military manual, Hardee’s Rifle and Light Infantry Tactics. One division under former U.S. vice-president Maj. Gen. John Breckinridge was positioned east of Stones River on the Lebanon Pike. Eight hundred yards behind Breckinridge, Maj. Gen. Patrick Cleburne deployed his hard-fighting division. Maj. Gen. John P. McCown’s division of Hardee’s corps was placed in reserve on the east side of the river.

Like Polk, Hardee was also critical of Bragg’s command. Hardee was troubled by the terrain Bragg chose to defend and would later write in his after-action report, “The field of battle offered no peculiar advantage for defense.” He was concerned that the open fields skirted by cedar brakes would give cover to the enemy soldiers. “The country on every side is entirely open and accessible to the enemy,” he complained. Large boulders, deep crevices, and heavily wooded areas broken by farm fields made it difficult terrain for cavalry or artillery to operate. Stones River was another potential danger—Bragg’s army was split on either side of it. Although it could be forded anywhere, a heavy rainstorm might raise the river enough to cut off the two corps from one another.

Fighting Across Stone’s River

Rosecrans expected the Rebels to attempt to defend Stewart’s Creek, 10 miles northwest from Murfreesboro. But when Crittenden’s corps waded through the bone-chilling creek water on December 29, all it found was an enemy cavalry picket. McCook, meanwhile, moved down the Franklin Pike toward Murfreesboro. Wheeler’s troopers desperately tried to slow down the Federals, but they were heavily outnumbered and forced back into Murfreesboro.

At 3 pm, Brig. Gens. Patrick Wood’s and John Palmer’s divisions of Crittenden’s corps caught sight of Breckinridge’s division on the east side of Stones River. When Crittenden rode up to join Palmer and Wood around 5 pm, orders came from Rosecrans to push on to Murfreesboro. With darkness now blanketing the countryside, Crittenden obediently ordered an advance, despite the protests of his two division commanders, who urged him not to advance. Finally, Crittenden halted his force and decided to try and find Rosecrans, who had just arrived. Rosecrans immediately canceled the order.

The cancellation came too late for Colonel Charles Harker’s brigade in Wood’s division, which already had moved across the river. After driving in Confederate pickets and pushing them up Wayne’s Hill, where a battery was set up, the 51st Indiana of the 3rd Brigade almost took both the battery and the hill. Only the arrival of the 9th Kentucky and 41st Alabama regiments saved the guns and forced the 51st Indiana to fall back. Harker’s brigade withdrew across the river at 10 pm.

Two hours later, more troops were on the offensive, but this time they were Confederates. Wheeler and his men rode out of camp, crossed Stones River and disappeared into the darkness and rain. Headed up the Lebanon Pike, Wheeler planned to strike the Union rear. Five miles up the pike, the troopers reined their mounts west and smashed into a Federal wagon train at dawn, torching 20 wagons. For the rest of the day Wheeler’s troopers spread havoc, burning hundreds of wagons and taking numerous prisoners. By nightfall, Wheeler had seriously damaged the Federal supply line and captured enough weapons to arm an entire brigade, besides remounting his men with fresh horses. Wheeler rejoined Bragg the following day.

While Wheeler was causing grief in his army’s rear, Rosecrans spent most of the 30th moving his men into position for the coming battle. Crittenden’s corps, with Stones River on one side, extended across the Nashville Turnpike. Maj. Gen. Lovell Rousseau’s division, from Thomas’s center, was placed in reserve, while Brig. Gen. James Negley’s division took up position with Crittenden on its left and the Wilkinson Pike and McCook on its right. Rosecrans’s plan for the coming day was to send Crittenden across Stones River, break through Breckinridge’s division, and drive the Rebels into Murfreesboro. While this was taking place, Thomas, along with Palmer’s division, was to move across the river and push toward Murfreesboro. McCook on the right flank was to take up a defensive position if attacked. If not, he was to conduct a holding attack against the Confederate forces facing him. Concerned about his right wing, Rosecrans ordered McCook to extend his campfires beyond his right flank to give the Rebels the impression that there was a much larger force on their left.

Bragg, for his part, was worried that his left flank, which did not extend beyond the Franklin Road, might be turned by McCook. To counter this threat, Bragg ordered McCown’s division to advance past the road. Cleburne’s division was dispatched to the left flank as well to support McCown, with Hardee going along to accompany his two divisions. Breckinridge remained where he was. Bragg’s plan of battle for the next day was similar to Rosecrans’s. He intended to hit the enemy’s left flank. Believing that McCook would launch the major assault, Bragg informed Hardee and Polk of his intention of striking the Federals first along the Nashville Turnpike. Polk, however, had another idea. With the Confederate left flank extended, Hardee’s two divisions could attack the Federal right. Then Polk’s command would perform a “constant wheel to the right” and drive the Federals to the river. Wharton’s cavalry, meanwhile, would hit the Federals in the rear, cutting off their supply line to Nashville. Bragg agreed to the change in plans.

That night, as the armies bedded down in anticipation of the next day’s battle, a battle of another sort broke out. Blue and gray bands began to play their favorite tunes, “Yankee Doodle” and “Dixie.” The two sides exchanged other tunes before the bands joined in to play the nostalgic “Home Sweet Home.” When the music died away for the night, it would not be long before the killing began.

Breaking the Union Right

At 2 am, Brig. Gen. Philip Sheridan, commanding the 3rd Division in McCook’s corps, was wakened by one of his brigade commanders, Brig. Gen. Joshua Sill. Across the fields that separated the opposing armies, the sound of moving infantry and artillery could be heard resonating from the Confederate lines. Sill informed Sheridan of his fears that the Rebels might be massing for an attack on the Union right. Sheridan and Sill hurried to McCook’s headquarters to inform the wing commander of the threat. McCook was not overly concerned, confident that the morning attack by Crittenden would stall any Rebel attack on his wing.

Sheridan and Sill did not share McCook’s confidence. They returned to division headquarters, where Sheridan ordered the 15th Missouri and 44th Illinois Regiments from Colonel Frederick Schaefer’s brigade to reinforce Sill. Sheridan made sure that all his men were under arms and ready for daylight. Unfortunately for the rest of the Union right wing, Brig. Gens. Richard Johnson and Jefferson C. Davis were not as diligent in readying their divisions. They too had received a warning from McCook to have their men prepared for a possible Confederate attack in the morning, but they had simply passed the order down to their brigade commanders, and little more was done about it. One of Johnson’s brigade commanders, Brig. Gen. August Willich, sent out a company to scout out the woods beyond the picket line to see what the enemy was doing. They reported back that they saw nothing suspicious.

A cold gray mist enveloped the countryside on the morning of December 31. The men of Willich’s brigade, holding the far right of McCook’s wing, began to make breakfast fires and heat their coffee. Half the horses from Captain Warren Edgarton’s 1st Ohio Battery E were led away to be watered. With Brig. Gen. Edward Kirk’s brigade positioned to the left of Willich and more pickets out on patrol, worries about a Rebel assault lessened as the morning advanced. The still-sleepy soldiers relaxed.

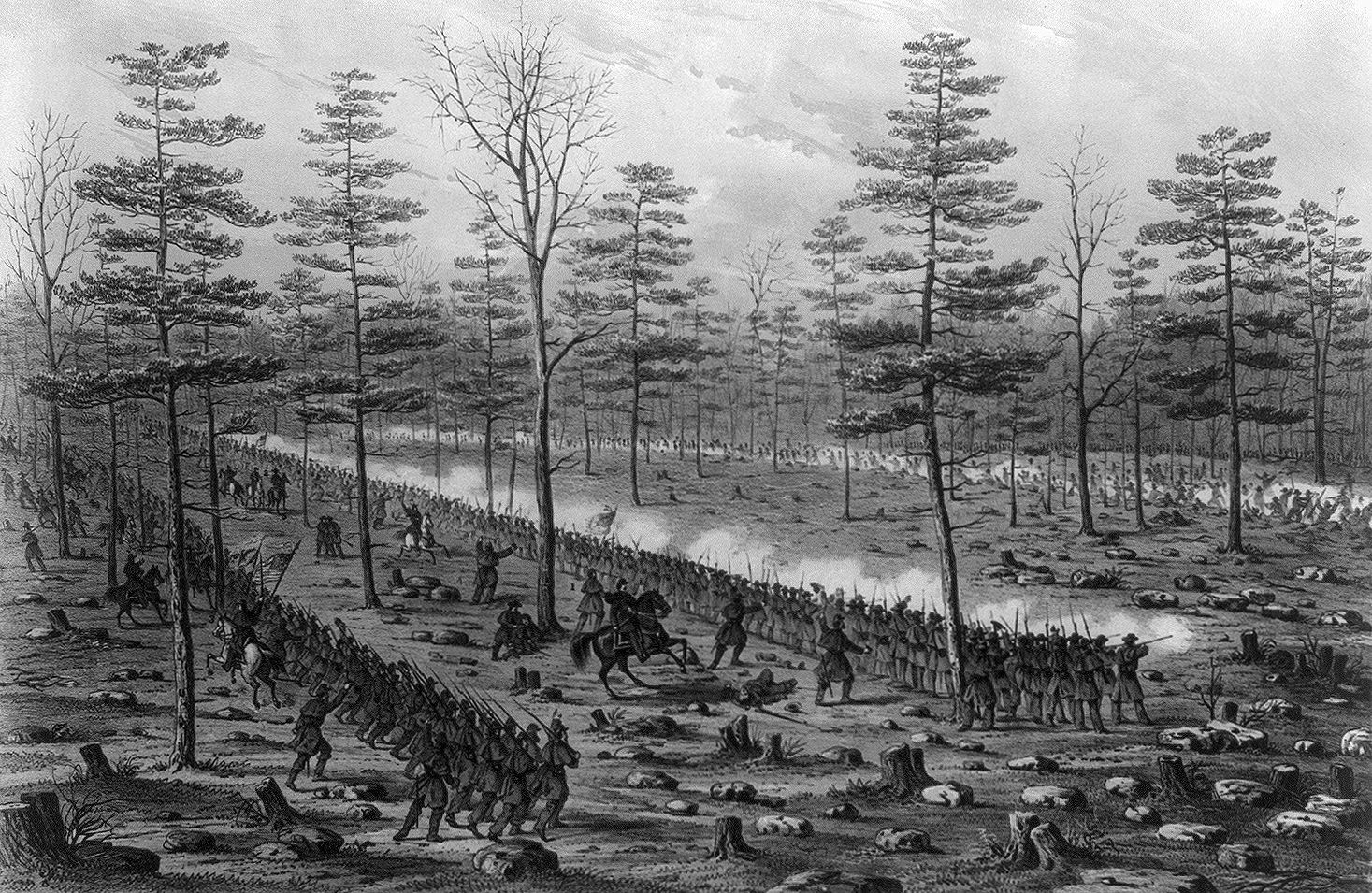

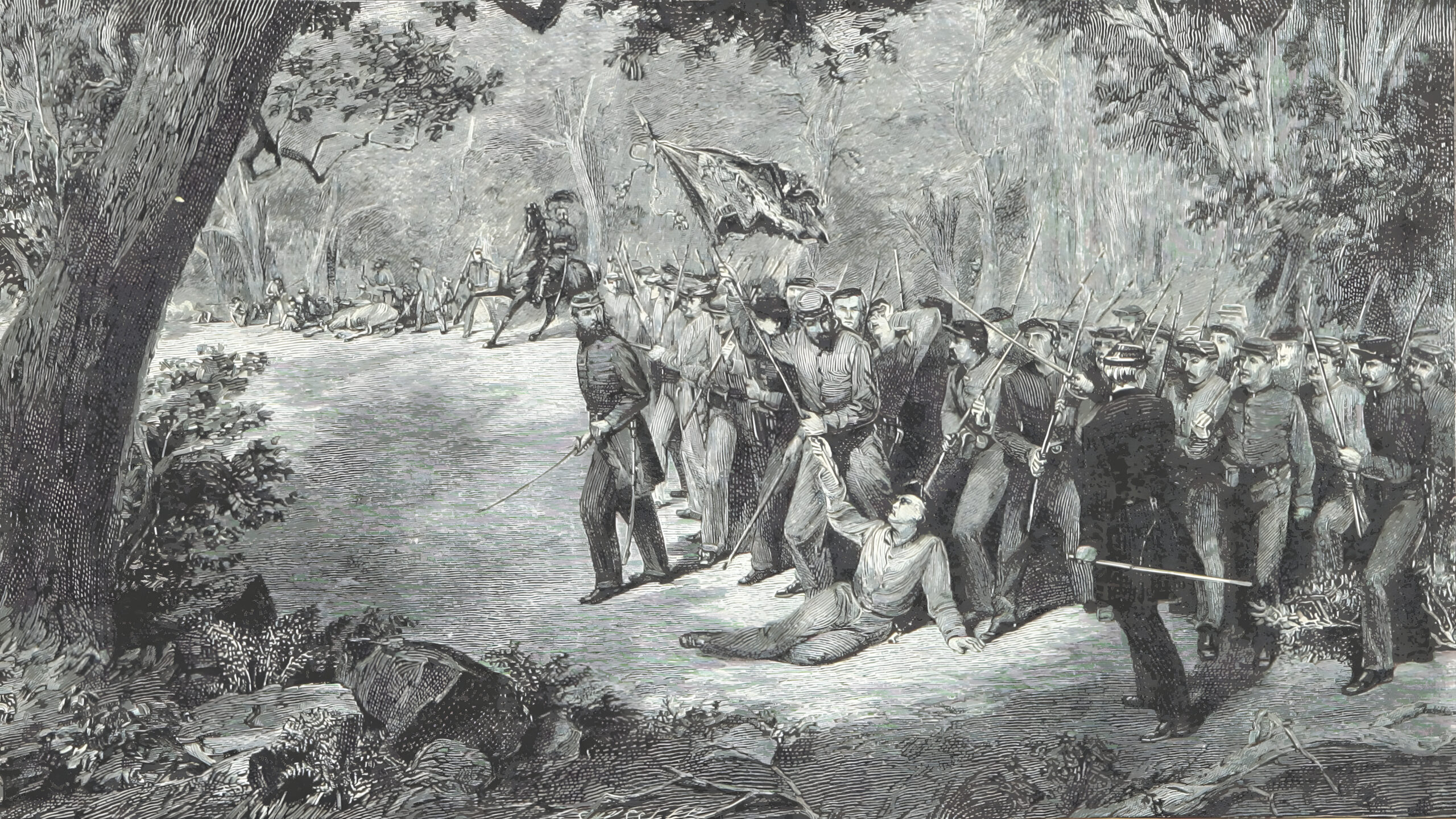

Then, at 6:22 am, thousands of Confederates in a double line, with skirmishers out in front, charged. McCown’s division led the way, with Cleburne’s division 500 yards behind it. “We could see the enemy advancing over the open country for half a mile in front of our lines,” Kirk reported. “Their left extended far beyond our right, so as to completely flank us.” Braving canister fire from Edgarton’s guns, McCown’s graybacks pushed hard for Kirk’s brigade at the junction of Gresham Lane. To buy time for Edgarton’s battery, whose horses had yet not returned, Kirk ordered the 34th Illinois to counterattack. Fire from the 10th Texas stopped the 34th in its tracks and forced it back on Edgarton’s guns. The onrushing Confederates quickly drove off the infantry and overran the battery. Kirk went down with a bullet in his thigh. Willich’s brigade was next. Most of the regiments in the brigade faced south, while the Rebels were coming fast from the southeast. Willich was away from his post, having ridden over to division headquarters. Kirk’s panic-stricken men tumbled through Willich’s lines, stumbling for the rear. Willich’s men broke as well. “A complete panic prevailed. Teams, ambulances, horsemen, footmen and attaches of the army, black and white, mounted on horses and mules, were rushing to the rear in the wildest confusion,” wrote Colonel William Gibson, who was commanding the brigade in Willich’s absence.

Willich returned to take command and unknowingly began shouting orders at Confederate troops he thought were his own. He soon discovered his mistake when his horse was shot from under him and he was taken prisoner. The Federal right was in shambles. Two brigades had broken, suffering over 900 casualties and another 1,000 captured, along with losing eight guns. The very confusion, however, caused the Confederate plan to go astray. McCown’s division continued after the retreating bluecoats in a northwestward direction, instead of swinging to the right as planned. Cleburne, unaware of McCown’s pursuit, swung his division to the north and soon discovered that he was no longer acting in support of McCown, but was on his own and taking heavy fire.

Cleburne’s division soon ran into Davis’s division, which was now on the extreme right flank of the Union army. Hearing firing on his right, Davis had ordered Colonel Sidney Post’s brigade to move from its original position to Gersham Lane and face south toward Franklin Road. There, some of the regiments found cover behind a rail fence.

Brigadier General Bushrod Johnson’s brigade of Cleburne’s division came under Federal artillery fire as it moved out of the woods on either side of Gersham Lane and advanced toward Post’s bluecoats. The intense fire forced Johnson’s Tennesseans to give ground and begin firing back. Johnson ordered up artillery, which quieted the Yankee guns. The Tennesseans now jumped to their feet and charged the enemy guns, which were in the process of limbering up. Horses and men went down as the Federals desperately tried to save the guns by dragging them off by hand. They were just in time. Johnson’s brigade soon overran Post’s position. The 74th and 75th Illinois held off the attacking Confederates briefly before they too were forced to fall back.

To the left of Bushrod Johnson, Brig. Gen. St. John Liddell’s brigade, which had become separated from the rest of Cleburne’s brigades, linked up with Brig. Gen. Evander McNair from McCown’s division. Together, they prepared to attack the Federals positioned behind the rail fences on Gersham Lane. Liddell’s brigade charged forward, coming under heavy fire. McNair, who was ill, was slow in moving out, leaving Liddell unsupported in his attack. Liddell’s men, undaunted, surged forward and forced Colonel Philemon Baldwin’s brigade to retreat.

Cleburne’s other two brigades, commanded by Brig. Gens. Lucius Polk and S.A.M. Wood, struggled through the thick cedar woods east of Gersham Lane and came under fire from soldiers in Colonel William Carlin’s brigade. Carlin attempted to withdraw his command in good order, but he was wounded and the retreat of the 101st Ohio and 21st Illinois quickly turned into a rout. “Everything was perfect confusion,” wrote Union Private Jay Butler, “men and horses running in every direction and Rebels after us, firing upon us and yelling like Indians.” The 15th Wisconsin, under Heg, fought a brief rearguard action, buying enough time for the brigade and artillery to get away.

“You’ll Soon Find it the Hottest Place You Ever Struck!

While Rosecrans’s right was being shattered, Wharton and his cavalry galloped behind Federal lines. Pushing Colonel Lewis Zahm’s cavalry brigade out of the way, Wharton’s men captured hundreds of prisoners, including the mortally wounded Kirk, who was being taken to the rear. Polk’s assault to the right of Cleburne was not going as well. The night before the attack, Polk had decided to reorganize his corps because of the rough country that lay before them. Instead of having Withers’s division lead the attack with Cheatham’s division following as originally planned, Polk ordered Cheatham to take command of the two left brigades in Withers’s front line, along with the two left brigades in his own division. At 7 am, Cheatham ordered Colonel J.Q. Loomis to lead his Alabama brigade across 300 yards of cornfields and open woods against Colonel William Woodruff’s brigade of Davis’s division positioned on a ridge. To the left of Woodruff was Sill’s brigade, which held Sheridan’s right flank. This was only one of many piecemeal attacks ordered by Cheatham that morning, causing some to accuse him afterward of being drunk during the battle.

The Confederates managed to capture part of the rail fence held by some of the Federal regiments. For half an hour, both sides pummeled each other until Union enfilading artillery fire finally drove back Loomis’s depleted brigade. In the fierce fighting, Sill took a bullet to the head, killing him almost instantly. As the Alabamians staggered back to Confederate lines, they were heckled by the Tennessee and Texas soldiers from Colonel A.J. Vaughan’s brigade of Polk’s division. “You’ll soon find it the hottest place you ever struck!” countered an angry Alabamian. He was right, as Vaughan’s soldiers were soon to realize to their own discomfort.

Vaughan’s men smashed into the Federal lines, sending two enemy regiments back before they rallied. Then the Federals counterattacked, recapturing the fence line, and drove off the Rebels in their turn. Not all the southerners retreated. The 9th Texas continued to fight on, enduring a deadly crossfire before driving off the Illinois troops with a wild charge. At the same time, the rest of Vaughan’s brigade and Loomis’s brigade, now under the command of Colonel J.G. Coltart after Loomis was wounded by a limb knocked from a tree, charged a second time. Woodruff’s men were driven back to the Wilkinson Pike, covered by the 8th Wisconsin battery.

Houghtaling’s Guns

At 8 am, Colonel A.M. Maginault’s brigade from Withers’s division moved forward to attack to the right of Vaughan and Coltart. They were late in launching their attack and soon came under artillery fire. Then infantry fire from the 88th Illinois of Sill’s brigade, now under the command of Colonel Nicholas Greusel, turned them back. Half an hour later, Maginault was back, this time supported by Brig. Gen. George Maney’s brigade of Cheatham’s division. By now Sheridan had reformed his lines, pulling back his regiments on the right flank to the north side of a narrow lane at the Harding farm, while two other regiments short on ammunition were withdrawn behind a battery. The 4th Indiana Battery under Captain Asahel Bush set up near the Harding farm while the 1st Illinois Battery under Captain Charles Houghtaling unlimbered 600 yards northeast of the farm. Maginault’s brigade was torn apart by artillery fire, and a charge by Colonel George Roberts’s brigade of Sheridan’s division sent the rapidly tiring Confederates reeling back. Maginault consulted with Maney, and they decided that the Federal batteries spewing havoc among their men had to be taken out. Each brigade would go after a battery.

Maney’s brigade moved forward to take out Bush’s guns and supporting infantry near the Harding house. Moving over a ridge, they came under devastating artillery fire from Houghtaling’s guns—Maginault hadn’t captured them yet. Maney and his officers believed they were taking friendly fire. Lieutenant R.F. James of the 1st and 27th Tennessee Consolidated galloped forward to investigate. Fifty yards from the Federal position, he was shot down. Still, Maney was not convinced the guns were in Yankee hands. Even after a second officer barely escaped with his life after getting within 40 yards of the battery, some Confederate officers harbored doubts. A color-bearer from the 4th Tennessee marched forward and waved his flag for 10 minutes to draw enemy fire, and a second color-bearer planted his Rebel banner on a feed crib, which the Federal guns promptly fired on, before the officers were convinced the guns were in enemy hands. Tennessee Private Sam Watkins, on the skirmish line that day, was disgusted. “John Barleycorn was general in chief,” he wrote after the war. “Our generals, and colonels and captains, had kissed John a little too often. They couldn’t see straight. They couldn’t tell our own men from the Yankees.”

Four guns from Smith’s battery commanded by Lieutenant William Turner were quickly brought up by the Confederates and opened fire on Houghtaling. An artillery duel ensued. At the same time, Vaughan’s brigade moved up behind Maney’s left and took shelter on the far side of the ridge to await further orders. More Confederate brigades would soon join the mix. The situation looked grim for Sheridan. A quick investigation of his right revealed that Davis’s division was in full retreat. Sheridan was now the right flank of the army. He would have to pull back his own right to save his division. Sheridan ordered Greusel and Schaefer to fall back from Wilkinson’s Pike into the thick cedar woods to the rear.

Fight for the Cedar Woods

Bloody fighting soon broke out in the rock- strewn cedar woods, which were dotted with caverns. Polk’s brigade engaged in a fierce firefight with Schaefer’s men. To the south, Maginault’s brigade was attempting to capture the guns of Bush and a 1st Missouri battery under Captain Henry Hescock which had taken up position on a knoll near the junction of McFadden’s Lane and Wilkinson’s Pike. Roberts’s supporting infantry, holding the apex of Sheridan’s line, threw back the attack. Another attempt was launched, this time with the aid of two regiments from Brig. Gen. J. Patton Anderson’s brigade of Withers’s division. The Confederates took a terrific hammering from the Federal guns, which threw back the attack with heavy losses. More attacks failed. Roberts continued to the hold his position, but not for long. Sheridan’s outnumbered men had fought brilliantly, throwing back attack after attack and inflicting heavy losses on their adversaries, but now things looked desperate for them. Their cartridge boxes were just about empty.

Rosecrans, meanwhile, had heard distant musketry fire on his right flank, but he assumed that it was McCook holding the Rebels in check. He was more concerned with the three divisions crossing Stones River in preparation for an assault on Bragg’s right flank. Word reached the Union commander that his right wing was broken, but a courier from McCook reported only that the right wing was under attack and needed reinforcements. Rosecrans still believed everything was going as planned. The sound of battle moving to the north and the rear hinted that perhaps this was not true. Another officer from the broken right confirmed the worst. Rosecrans erupted in a frenzy of manic activity, dashing off orders to brigades, regiments, companies—any body of men he could find. “He failed to produce an impression as one who grasped the whole momentous situation with the hand of a master,” the official historian of the 41st Ohio would judge drily.

The planned attack on the Confederate right was canceled, and Crittenden was ordered to send one of his divisions back across the river. Wood was ordered to take two brigades from his division and move to the right immediately. “We’ll all meet at the hatter’s, as one coon said to another when the dogs were after them!” hollered Wood to Rosecrans as he rode away.

Rousseau was ordered to take up position to the right rear of Sheridan’s tenuous hold on the cedar woods at 9:30 am. Rosecrans rode on to shore up his defenses, ordering units here and there, rallying his men. When Lt. Col. Julius P. Garesche, Rosecrans’s chief of staff, begged him to be more cautious in exposing himself to enemy fire, Rosecrans retorted: “Never mind me. Make the sign of the cross and go in. This battle must be won.” Later that day, Garesche would be beheaded by a Confederate cannonball that spattered his brains over Rosecrans’s overcoat.

Reforming on the Nashville Pike

Brigadier General Alexander Stewart of Cheatham’s division led his brigade forward in another attack on Roberts. Roberts was killed and Houghtaling was wounded. Sheridan quickly gave the order to withdraw when he arrived on the scene. “There was no sign of faltering with the men, the only cry being for more ammunition, which unfortunately could not be supplied,” Sheridan wrote afterward. Cheatham, seeing the Federals withdrawing, led Maginault’s and Maney’s brigades after them. Sheridan’s other shot-up brigades—Schaefer’s and Greusel’s—were withdrawing as well.

Rousseau’s bluecoats were not in position long before they too came under attack from McCown’s division. The Federals began falling back to reform on the Nashville Pike, a position that had to be held at all costs. Colonel John Beatty’s brigade held in the thickets, not knowing that the rest of the division had fallen back, and continued to blunt the Confederate attacks. Rousseau had told him earlier to hold “until hell freezes over.” Finally realizing how exposed he was, Beatty ordered a retreat just about the same time that Lucius Polk’s brigade hit him again. “I conclude that the contingency to which General Rousseau referred—that is to say, that hell has frozen over” had occurred, Beatty recalled. He and his men broke for the rear.

When Roberts’s apex was forced back, Colonel Timothy Stanley’s brigade of Brig. Gen. James Negley’s division, which was holding to the left, found itself in trouble as well. Nailed by Confederate artillery and assaulted by Anderson and Stewart, Stanley’s men broke. Another of Negley’s brigades, commanded by Colonel John Miller, was hit next. They were soon forced back as well.

The Confederates pushing up the Nashville Pike under Brig. Gen. James Chalmers struck Brig. Gen. Charles Cruft’s brigade of Palmer’s division west of Cowan’s Farm. Chalmers’s poorly armed Mississippians (some carrying only sticks) surged forward with a Rebel yell, crossing cotton and wheat fields. Stopping 50 yards from Cruft’s men, they began trading fire with the Federals. For half an hour the two sides blasted away at each other, with the Confederates taking heavy casualties, including Chalmers, who was knocked unconscious by a piece of shrapnel to the forehead. Finally, the Confederates began to fall back.

Brigadier General Daniel Donelson’s brigade of Cheatham’s division struck next. Rushing out of their rifle pits, Donelson’s men split into two streams when they reached Cowan’s Farm and Chalmers’s men failed to get out of the way. Two and half regiments moved toward Cruft, while the other two and a half regiments pushed northward toward the so-called Round Forest, a key bit of real estate that would be soon become known by a more graphic and descriptive name, Hell’s Half Acre. It was held by Colonel William Hazen’s brigade of Palmer’s division. Cruft sent out the 1st Kentucky to meet the Rebels in the cotton fields in front of their position. The Confederates quickly pushed them back. Then Stewart’s men struck one of Cruft’s regiments in the rear. Outflanked and with Donelson’s Tennesseans breaking through his first line, Cruft was forced to withdraw.

“Shepherd, take your brigade there and stop the Rebels,” Maj. Gen. George Thomas ordered Lt. Col. Oliver Shepherd of Rousseau’s division. Shepherd’s men were well-trained regulars, and he quickly led them into the fray. The fighting was bloody, with 400 Federals going down and the rest finally forced to retire. But Stewart’s brigade was hurting too, and the Confederates held up at the edge of the cedars. The 8th and 16th Tennessee of Donelson’s brigade had suffered 500 casualties of their own.

“Give Them a Blizzard, and Then Charge With Cold Steel!”

Part of Donelson’s brigade pushed on toward the Round Forest. The Federals meanwhile quickly reinforced the key position, which was formed into a V-shape protecting the railroad and the Nashville Pike—the army’s crucial supply line. The Round Forest was the apex of the V. Brig. Gen. Milo Hascall knew the importance of the forest to the Rebels; he would later report: “If they [the Confederates] succeeded in carrying this they would have turned our left, and a total rout of our forces could not then have been avoided.”

Donelson’s men never reached the Round Forest as they came under heavy fire from the Federals. The 2nd Missouri from Schaefer’s brigade was ordered into the fight, and the added firepower helped stop the new Confederate advance. The fighting temporarily died out in the forest, but it was raging elsewhereas Cleburne and McCown were driving for the Nashville Pike from the west. Brig. Gen. Mathew Ector’s brigade was fighting it out with Colonel Samuel Beatty’s brigade of Brig. Gen. Horatio Van Cleve’s division. The Confederates got the worst of the fight and were forced into retreat, with Beatty in close pursuit. Near the Asbury Church, Colonel James Fyffe’s brigade joined Beatty, as did Colonel Charles Harker of Wood’s division.

The Federals had barely arrived when they were hit hard by Cleburne’s division and sent reeling. Rosecrans desperately rallied the troops and formed a line as best he could to protect the Nashville Pike and the rear of his army from Cleburne. “Men do you know how to be safe?” he called to the hard-pressed soldiers in the Round Forest. “Shoot low! But to be safest of all, give them a blizzard, and then charge with cold steel!” It was good advice, as far as it went. At any rate, the Confederate attack was beginning to run out of steam. Being so close to success, Cleburne’s men began to fall back. It was 3 pm, and Cleburne’s men had been fighting all day with little rest. They badly needed ammunition and reinforcements.

Cleburne was not the only one needing reinforcements. Polk needed them too as he prepared to storm the Round Forest. East of the Stones River sat Breckinridge’s well-rested division, which was sorely needed on the west side of the river. Around 10 am, Bragg had sent Breckinridge a verbal order to reinforce Hardee, an order that Breckinridge would deny he ever received. Instead, for the next several hours Breckinridge remained on the east side of the river, obeying an earlier order from Bragg to engage a phantom Union force reportedly moving toward him. Eventually, word reached Bragg that the enemy on the east side was a mere a handful of sharpshooters. He was furious. “These unfortunate misapprehensions on that part of the field withheld from active operations three fine brigades until the enemy had succeeded in checking our progress,” Bragg wrote. He ordered Breckinridge to send reinforcements across the river.

Around 1 pm, Breckinridge’s brigades began to cross Stones River. Brig. Gens. Dan Adams’s and John Jackson’s brigades were the first to arrive, reaching Polk an hour later. Polk had been ordered to attack the Round Forest and smash the Federal center. At the very least, Bragg hoped that by concentrating on the Round Forest, it might draw off units holding Rosecrans’s right, enabling Hardee to push on to the Nashville Pike. Instead of waiting for more brigades from Breckinridge’s division to arrive, Polk ordered Adams and Jackson to attack the Round Forest immediately. Federal batteries played havoc with the advancing Rebels once they moved past Cowan Farm. Still they kept coming. Infantry fire poured into their ranks. After a half hour of this hell, Adams ordered a withdrawal. He left behind 426 dead or wounded on the field.

Now it was Jackson’s turn. His men charged the Federal stronghold without hesitation. “On they came in steady column, notwithstanding the murderous fire,” Indiana Private Gilbert Stormont observed with grudging admiration. “We could see their men falling like leaves, but the broken ranks were filled, and they held their ground with a heroism worthy of a better cause.” It was for naught. The Union line held and Jackson’s brigade added another 291 casualties to the day’s tab. After one last, futile assault by Breckinridge’s reinforcements, the fighting ended for the day.

“No Better Place to Die Than Right Here”

As darkness settled in, thousands of wounded and dead on both sides littered the fields and cedar woods. The cries of the wounded pierced the darkness. It had been a bloody day. For Bragg it seemed that victory was imminent—his men had driven the Union Army back three miles on their right. He telegraphed Richmond with the uncharacteristically upbeat news that “God has granted us a Happy New Year.” Bragg was sure that Rosecrans would retreat to Nashville. Wagons had already been spotted heading that way. Unknown to Bragg, the wagons were merely carrying off the wounded. Rosecrans, for his part, wasn’t planning on going anywhere.

At the headquarters of the battered Army of the Cumberland, Rosecrans conferred with his generals on their next course of action. Should they hold their ground or retreat? Accounts vary about the conference, with some giving Thomas credit for encouraging Rosecrans to stay put with this fatalistic observation: “General, I know of no better place to die than right here.” Others give credit to Sheridan for backing Thomas in the advice. At any rate, it was up to Rosecrans to make the final decision. He would later report: “After careful examination and free consultation with corps commanders, followed by a personal examination of the ground, it was determined to await the enemy’s attack in that position; should not the enemy attack, offensive operations should be assumed.”

Torches seen flickering along Overall Creek induced Rosecrans to believe the Rebels were forming in his rear. In actuality, it was only Federal cavalrymen lighting fires to warm up the infantry. Possibly this led Rosecrans to decide to stay and fight. Whatever the reasons, the Federals did stay, and over the next two days they would deny Bragg his prematurely claimed victory. By the time the fighting was over, Bragg had lost 9,239 killed or wounded, while Rosecrans had suffered 9,532 casualties. During the subsequent Confederate retreat, Bragg confronted a straggling soldier and asked him if he belonged to Bragg’s army. “Bragg’s army?” said the soldier. “He’s got none; he shot half of them in Kentucky, and the other got killed up at Murfreesboro.” Bragg had no response—there was nothing else to say.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments