By Patrick J. Chaisson

“Peiper must be stopped!”

Lieutenant General Courtney M. Hodges, commanding the U.S. First Army, looked up from his maps and saw chaos everywhere. All across the Ardennes Forest, American forces were reeling from a surprise German counterattack that struck on the morning of December 16, 1944. While some frontline units stubbornly held their ground, others simply disappeared—annihilated by the Nazi juggernaut.

One marauding enemy column particularly worried General Hodges. This was Kampfgruppe Peiper, the spearhead of the German 1st SS Panzer Division. Named for its commander, SS Lt. Col. Jochen Peiper, this powerful force was headed for the crossroads city of Liege, first stop toward its ultimate objective of Antwerp and the Belgian coast.

Amid reports of mass surrenders on the front lines and English-speaking German commandos terrorizing the First Army rear area, Hodges’s staff began hearing rumors of a massacre involving Kampfgruppe Peiper at Baugnez, near Malmedy. There, on December 17, some 80 American soldiers were ruthlessly gunned down after surrendering to Peiper’s troops.

Codename “Daredevil”

Even as Kampfgruppe Peiper rampaged westward toward Liege, Hodges looked for help to defeat it. He first contacted the Ninth Army, which promised the 30th Division then refitting near Aachen. Hodges then appealed to General Dwight D. Eisenhower, Supreme Allied Commander in Europe, for release of the Theater Reserve. Ike agreed, and within hours the 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions were on their way from camps in France to the Ardennes.

But getting these reinforcements into position would take time, a precious commodity. Small groups of combat engineers, antitank gunners, and infantry bought vital hours when they blew bridges and set roadblocks across Peiper’s path, hindering his advance. Even antiaircraft crews got into the fight, firing their 90mm guns over direct sights.

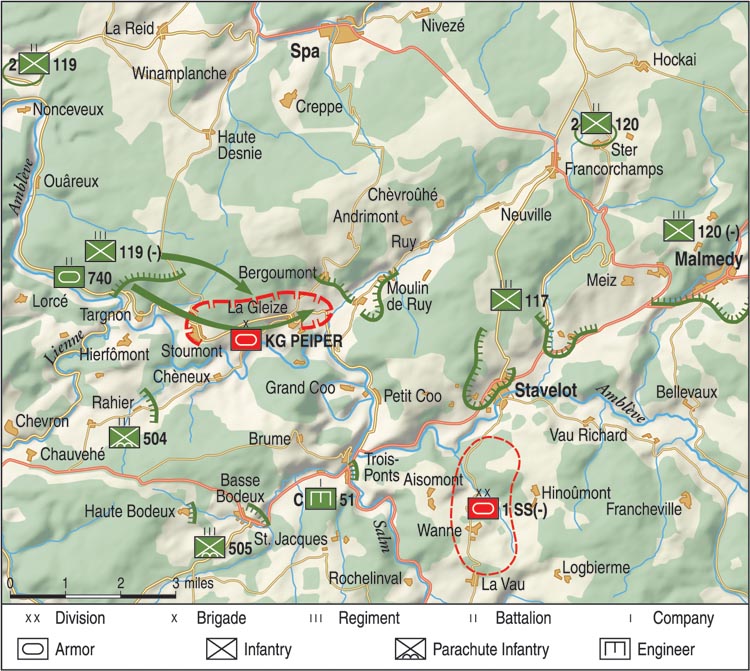

First Army needed accurate information to find and then halt the German advance. Hodges’s staff sent out tiny, unarmed Piper Cub spotter planes to track the progress of Kampfgruppe Peiper as it headed west along the Ambleve River Valley. Crashing through Ligneuville, Stavelot, and La Gleize, the enemy column was, by midday on December 18, only 12 road miles from First Army headquarters, located in the resort town of Spa, Belgium.

Hodges pushed his reinforcements, the 30th Infantry and 82nd Airborne Divisions, into blocking positions along the Ambleve Valley. However, to stop Peiper’s tanks Hodges needed armor of his own. His staff could find only one available unit, the 740th Tank Battalion, codenamed “Daredevil.”

The “Gizmos” of the 740th Tank Battalion

There was a catch: the Daredevils had no tanks.

The 740th Tank Battalion, so desperately thrust into action against Kampfgruppe Peiper, was formed in March 1943 at Fort Knox, Kentucky. Within a few weeks the 740th moved to a heavily guarded enclosure far from the main post. All passes were canceled, and each soldier was sworn to secrecy. Only then did the troops learn their new mission—the 740th was to become a “special” outfit, equipped with searchlight tanks designed to illuminate the battlefield at night.

Everything about the Canal Defense Light (CDL) tank was classified. Built on an M3A1 medium tank chassis, the CDL, or “gizmo” as 740th crews called it, used a high-intensity carbon arc lamp inside the turret to light up the night sky while blinding enemy defenders. Orders soon arrived transferring the 740th to Camp Bouse, Arizona, for intense training.

The battalion arrived at Camp Bouse, part of the Desert Training Area, in October 1943. The men encountered scorching heat, constantly blowing wind, and dust that seeped into everything—engines, clothing, even food. Very few gizmos were available for training, so the men spent their days performing menial work details. Morale plummeted, and the battalion commander was relieved after his unit failed a major inspection.

Lt. Col. George Rubel Turns the 740th Into a Fighting Unit

On November 12, Lt. Col. George K. Rubel took command of the 740th Tank Battalion. A wiry, 40-ish professional soldier from Phoenix, Arizona, Rubel was a battle-hardened veteran of the North Africa campaign. He immediately set out to turn his battalion into the best tankers in the U.S. Army.

While Camp Bouse had few CDLs, there were plenty M4 Sherman tanks to go around, as well as piles of 75mm main gun ammunition. Rubel started his training program with the basics of driving and firing, day and night, over the roughest terrain.

Everyone learned to drive a tank. The entire battalion qualified with pistols, carbines, rifles, and Thompson submachine guns. Tankers lived on their iron chariots, learning to maintain the machines as if their lives depended on them.

All winter long the battalion trained. When time came to take the Individual Tank Crew Test, the 740th passed with an average score of 83.73 percent, the highest record in the armored force at the time. Top-shooting gunners even competed for an $80 prize offered for the best crew qualification score.

The unit was determined to do everything first and to do it better than anyone else. Out in the sprawling Arizona maneuver area the men built a dummy minefield, infiltration course, and even a mock city. First to run the infiltration course was Lt. Col. Rubel, shouldering a 31-pound machine gun while bullets snapped inches from his head.

The outfit learned to work as a combined arms team. Mortarmen quickly learned their trade, while service company drivers practiced delivering rations at night using map and compass.

Drawing on his own combat experience, Lt. Col. Rubel insisted that all tanks fight with the hatches open instead of buttoned up as armored force doctrine prescribed. “Everyone looked for targets,” Rubel later wrote, “and if they didn’t see the enemy first they didn’t live.” This practice paid many dividends later.

Reconfiguring as a Medium Tank Battalion

When the 740th Tank Battalion left Camp Bouse in April 1944, it was proficient both in standard tank missions and top-secret CDL tasks. Departing for England in July, the outfit came across Utah Beach three months later. The Daredevils then drove across France to join the First Army in November 1944.

While the 740th was marching toward the front, it received news that its special mission was cancelled and the unit would reconfigure as a standard medium tank battalion. This meant it was to reequip with M4 Sherman medium tanks and M5A1 Stuart light tanks. Unfortunately, First Army could lend the 740th only nine Shermans and a few M5A1s for familiarization purposes. Headquarters promised a full set of tanks to arrive perhaps by January. In the meantime, Rubel was directed to train and organize his battalion.

When German forces commanded by Field Marshal Gerd Von Rundstedt launched their Ardennes counteroffensive—which became popularly known as the Battle of the Bulge—on December 16, the 740th Tank Battalion was garrisoned in Neufchateau, a muddy Belgian village 50 miles behind the front lines. Within hours it was ordered to deliver its nine borrowed M4s to another unit. This left the Daredevils with three Stuarts and two scrounged assault guns.

On the 17th, Rubel paid a visit to First Army headquarters in Spa. There he learned the true extent of the German breakthrough and was told the 740th might have to fight as infantry, a task it was neither trained nor equipped to perform. Alarmed, Rubel returned to his command post and ordered the battalion to prepare for immediate action wherever it was needed. The situation looked grim.

Improvising a Solution

It was then that fate intervened in the person of Colonel Nelson M. Lynde, who was organizing the defense of Sprimont, an enormous vehicle repair depot sitting a dozen miles west of Peiper’s advance positions. Lynde informed First Army Headquarters that his depot had several tanks on hand ready to fight but no crews to man them. Someone remembered Rubel’s dismounted Daredevils, and at 12:45 pm on December 18, orders went out: move to Sprimont, draw all available armor, and prepare to defend the depot.

Two hours later, Captain James D. Berry (nicknamed “Red” for his shock of flame-colored hair) had Company C on the road to Sprimont. Rubel followed along with his command section and as many mechanics as he could muster. Time remained their chief adversary. Could the tankers get into action before Peiper attacked?

What the Daredevils found at Sprimont shocked them. The depot had but three tanks on the ready for issue line, and these were all missing essential pieces of equipment. Of the 25 armored vehicles present, most had been damaged in battle and then cannibalized for parts. They lacked working radios, weapons, and even tool sets. Not one tank carried a full load of ammunition.

Company C’s tankers swarmed on the equipment, laboring through the night to ready any vehicle they could get out the gate. There were old Wright-engined M4s next to newer tanks that for some reason all had British equipment. Staff Sergeant Charlie Loopey’s crew ended up with an M36 tank destroyer, while Sergeant John A. Thompson drew a duplex-drive amphibious Sherman that was missing the breech block for its 75mm main gun, not to mention all three machine guns. Captain Berry ordered Thompson and his “damned duck” to the rear of the column—they would fight.

Some tankers had to ride M7 self-propelled howitzers or M8 assault guns, neither of which they had ever trained on. The Daredevils also found at Sprimont two M24 Chaffee light tanks, part of a demonstration unit traveling around to acquaint U.S. troops with these new vehicles. The M24s would go into battle too, their crews learning by doing or dying.

Kampfgroup Peiper Captures Stoumont

While the Daredevil tankers hurried to prepare their mounts for combat, the situation along the Ambleve River was deteriorating badly. On December 18, Maj. Gen. Leland S. Hobbs’s 30th “Old Hickory” Division began moving into position along the northern shoulder of Peiper’s penetration. His 119th Infantry Regiment, commanded by Colonel Edward M. Sutherland, had advanced a reinforced battalion to occupy the village of Stoumont, blocking Kampfgruppe Peiper’s westward progress. Overnight the riflemen of 3rd Battalion, along with eight towed 3-inch guns of the 876th Tank Destroyer Battalion, dug in frantically to prepare for an SS attack.

It was not long in coming. At 7 am on the 19th, German paratroopers and SS panzergrenadiers accompanied by several Mark VI tanks emerged from the dense fog in front of Stoumont, firing on all suspected targets. Blasting the weary GIs from their fortifications, Peiper’s forces gradually gained a toehold in the village and began pushing the Americans out. A company of M4s from the 743rd Tank Battalion then arrived to help slow 3rd Battalion’s retreat, but by noon the Germans held all of Stoumont.

“They’re Bastard Tanks, but We’re Shooting Fools!”

Hobbs absorbed this news with great concern. His 119th Infantry had been knocked out of the last defensible position in the Ambleve Valley. Only the 119th’s understrength 1st Battalion remained as a reserve. If it failed to halt Peiper, the way to Liege and beyond would be wide open.

Hobbs ordered Sutherland to hold at all costs. He then begged First Army for additional armored support; the brave tankers of the 743rd were completely out of ammunition and had to resupply. Staff officers from the 30th Division spread out in all directions to find anyone who could help hold the line west of Stoumont.

One such officer discovered Captain Red Berry and Company C of the 740th posted near Sprimont. Pleading with Berry to join the 119th’s desperate defense, Hobbs’s messenger had to leave disappointed when the tank captain replied he could not leave his position without orders from higher authority.

Those orders were not long in coming. Hobbs contacted First Army, requesting the 740th Tank Battalion be attached to his 30th Infantry Division. This was quickly done, and by 2 pm the Daredevils were on the move.

Company C led off. Passing the 119th Regiment command post with his 14 badly needed Shermans, Captain Berry shouted encouragingly to a nearby officer: “They’re bastard tanks, but we’re shooting fools!” The ragtag column was just minutes away from a showdown with some of Nazi Germany’s deadliest tanks.

Taking Back Stoumont Station

The Ambleve River Valley was just wide enough on its north bank for a winding macadam road, paralleled partially by a rail line. Steep, wooded valley walls and the deep-running Ambleve further restricted mobility. The day was cold, and icy fog kept visibility down to 100 yards or less. There was only one way to go, down the road, and all afternoon the 1st Battalion of the 119th Infantry waited for Peiper’s tanks.

By 3:30 pm, in a cold drizzle and with dusk already starting to settle, the Germans had yet to appear. Lt. Col. Robert H. Herlong, commanding the 1st Battalion, conferred with Captain Berry. They decided to organize their own spoiling attack with Berry’s tanks covering the road while Herlong’s infantrymen protected their flanks. Their objective was Stoumont Station, a small granite block structure 800 yards away.

Third Platoon, led by Lieutenant Charles D. Powers, went first. Powers moved out cautiously, hugging the cliff side of the road while his machine guns riddled every possible target. The young lieutenant stood up in his turret, scanning for enemy tanks. He knew his Sherman was no match for a German medium Panther or heavy Tiger tank, so his crew’s lives depended on firing first and accurately.

The 740th Meets its First Panthers

The American column had advanced several hundred yards when Powers’s tank rounded a curve near Stoumont Station. Powers spotted a Panther, camouflaged with brush, 100 yards away. The gunner, Corporal Jack D. Ashby, fired once, his shot striking the gun mantle before deflecting down into the driver’s compartment and setting the enemy tank ablaze.

Moving forward, Powers’s crew identified another Panther. Again Ashby’s aim was true, his shell ricocheting off the Panther’s lower front slope plate. At this critical moment, Technician 5th Grade Howard Henry, the lieutenant’s loader, reported that the gun was jammed. Powers’s Sherman was helpless, and he waved the next tank up to finish off the wounded SS Panther.

The next vehicle in line was not even a tank. Staff Sergeant Charlie W. Loopey and his crew happened to draw an M36 tank destroyer at the Sprimont repair depot. Neither Loopey nor his gunner, Corporal William H. Beckman, had ever seen an M36 before but thought they could get this lightly armored tank killer running.

While Loopey’s M36 had only thin armor plate, it did carry a powerful 90mm cannon. Corporal Beckman used it to blast the second Panther, firing three rounds into the German behemoth until it caught fire.

By this time, Powers’s loader had cleared the jammed gun and the platoon leader resumed his place at the front. Advancing another 150 yards, Powers sighted a third Panther in the growing darkness. Ashby fired again, blowing the muzzle brake off the tank’s main gun. Two more shots put the Panther out of action permanently.

Lieutenant Colonel Herlong then halted the attack for the night. In 30 minutes of combat, Berry’s “bastard tanks” had recaptured Stoumont Station and blunted Peiper’s advance down the Ambleve Valley. Those months of hard, realistic training at Camp Bouse had paid off enormously, but the 740th’s war was just beginning.

“Too Cold to Sleep”

Protected by the three burning Panthers, Herlong’s riflemen dug in while their Daredevil brethren paused to resupply and rest. One tanker described his first night on the line at Stoumont Station: “It was too cold to sleep. All we could do was curl up in the tank like dogs.”

During the night, more tanks fresh from the Sprimont depot moved up to join Berry’s command. Fuel, ammunition, and radios also made their way forward. With artillery finally in position, American infantry and tankers prepared to resume their attack at dawn.

Weather conditions on the 20th remained poor, with cold, rain, and fog hampering visibility. This time, 2nd Platoon, led by 1st Lt. John E. Callaway, spearheaded the attack. Riflemen from the 1st Battalion, 119th Infantry provided flank protection while artillery and mortars stood by ready to fire. The day’s objective was Stoumont, two miles up the road, where Peiper’s main force was waiting.

Within minutes Callaway encountered a Panther, which his gunner dispatched with an armor-piercing shell that “opened its muzzle up like a rose.” Second Platoon then destroyed two SS half-tracks before running into a minefield that blew both tracks off Staff Sergeant Homer B. Tompkins’s M4. Though shaken up, Tompkins and his crew scurried to safety despite the mines and heavy German machine-gun fire.

“All Hell Broke Loose”

The Americans captured the hamlet of Targnon that day, moving to the outskirts of Stoumont before nightfall and violent SS counterattacks halted their progress.

Late in the afternoon, some American infantrymen occupied St. Edouard’s Sanatorium, a large brick building on the eastern edge of Stoumont. Situated on a steep hill, the sanatorium was a natural fortress. Whoever controlled it dominated the battlefield.

The enemy knew this and around 11 pm launched a fanatical counterattack. Between 50 and 100 SS panzergrenadiers, many screaming “Heil Hitler,” stormed St. Edouard’s and pushed the GIs out. Held up by a sharp cliff, the Daredevil tankers could do nothing to help. They had to wait for daylight to resume their attack.

At 4 am on December 21, 1st Lt. David Oglensky’s M4 crawled cautiously forward into the murk. Suddenly, according to driver Technician 4th Grade Robert Russo, “All hell broke loose.” Shells from a hidden antitank gun pierced Oglensky’s tank, forcing his crew to bail out. As the lieutenant boarded the next Sherman in line a panzerfaust rocket hit that tank, causing it to burst into flames. German panzerfausts then blasted two more M4s. In an instant, four tanks were destroyed, three of them burning fiercely. With the road blocked and St. Edouard’s Sanatorium in Peiper’s hands, the American attack bogged down almost before it started.

Had American commanders known of Kampfgruppe Peiper’s critical fuel shortage, they would have felt better about their situation. Already forced by the fuel shortage to cancel his drive on Liege, Peiper was even now radioing for permission to withdraw eastward. Peiper’s failure to capture vital bridges or American fuel depots meant his still powerful force was stuck in Stoumont, a difficult place to defend. Many of his heavy tanks, their gas tanks almost empty, started moving back toward La Gleize, where it was hoped that supply trucks would meet them.

Interestingly, almost a million gallons of gasoline were stacked in 5-gallon jerry cans along a road two miles north of Peiper’s route through the Ambleve Valley. Had the Germans known of it, they could have brushed aside the company of Belgian soldiers guarding this depot and solved their fuel problem.

Taking the Sanatorium

Back in Stoumont, the 119th Infantry Regiment and 740th Tank Battalion became part of Task Force Harrison, named for Brig. Gen. William K. Harrison, Jr., the 30th Infantry Division’s assistant division commander. Additional forces from the 3rd Armored Division had joined the battle north and east of Stoumont, pushing Peiper’s forces closer to their base in La Gleize. The noose was tightening, but first Stoumont had to be retaken.

From a hill near Targnon, Lt. Col. Rubel somehow acquired a self-propelled 155mm howitzer and began shelling the enemy-held sanatorium. Firing over open sights, Rubel’s personal artillery piece hurled about 50 high explosive rounds into the sturdy structure before darkness fell. The Germans inside were stunned by the massive bombardment but refused to yield.

Captain Berry thought of a way to throw the Germans out. That night he crawled completely around the sanatorium and found a place where a road might be built that could support tank traffic. Using volunteers from Company C and the infantry, Berry had a corduroy track built of shot-up trees and shell casings. Under cover of a thick smokescreen, service company recovery teams then towed off the four wrecked tanks from that morning’s fight.

By daybreak on the 22nd, Berry had maneuvered a platoon of M4s right up to St. Edouard’s. Firing through the windows, they kept the SS inside pinned down while soldiers of the 119th entered to recapture the main building, this time for good. Almost 250 civilians, many of them children, were later found dazed but unhurt in the sanatorium’s cellar.

Meanwhile, Powers and Loopey dispatched two more lurking tanks, one a Panther, the other a captured Sherman. This broke the back of Peiper’s defense, and the SS remaining in Stoumont quickly fled toward La Gleize. Coordinated attacks by the 2nd Battalion, 119th Infantry and Combat Command B of the 3rd Armored Division moving in from the north hurried them on their way. By nightfall, the U.S. advance had gone 2,000 yards past Stoumont while enduring ferocious German resistance.

No Daredevils Killed

Retaking Stoumont was a costly fight; in its first battle the 740th Tank Battalion lost five tanks and six men wounded. Miraculously, no Daredevils were killed. Infantry losses ran higher: the 1st Battalion, 119th Infantry suffered 106 casualties, including 18 killed, 60 wounded, and 28 missing.

On December 23, Task Force Harrison resumed its attack but ground to a halt short of La Gleize. Peiper’s men fought desperately, hemmed in by the 119th Infantry to their west, 3rd Armored Division columns attacking from the north, and paratroopers of the 82nd Airborne pushing steadily from across the Ambleve at Cheneux. Deadly German fire kept the Americans out of La Gleize that day, but everyone knew the end was near.

Peiper huddled in his basement headquarters while 95-pound shells from Rubel’s private cannon exploded overhead. It was after dark on December 23, and his nine-day race to the Meuse River had ended in total failure. Out of fuel, ammunition, and supplies, Peiper passed the word to his exhausted troops: “Destroy your equipment and escape on foot.”

What was left of Kampfgruppe Peiper abandoned La Gleize before dawn on Christmas Eve. The Germans left behind at least 28 heavy tanks, 70 half-tracks, eight armored cars, and numerous artillery pieces. Counting dead, wounded, and captured, Peiper lost over 85 percent of his original 5,800-man force. Escaping with him to the German lines were a mere 800 frozen, dejected soldiers.

There was no rest for the Daredevil tankers after taking Stoumont and La Gleize. On December 29, they joined the 82nd Airborne Division, working with that veteran unit in extreme cold and discomfort. Rubel’s tankers got along well with the aggressive 82nd, one paratrooper even noting, “The 740th was the only tank outfit that could ever keep up with us.”

The Daredevils After the Bulge

Once the Battle of the Bulge officially ended in January 1945, Allied forces began the final offensive in Western Europe. The Daredevils moved from unit to unit, supporting at times the 8th, 63rd, and 86th Infantry Divisions, as well as the 82nd Airborne, as they marched across Germany. While their infantry comrades occasionally went into reserve, the Daredevils stopped only for maintenance or resupply. They were always on the go, but that was how they preferred it. The men of the 740th realized that only hard, relentless fighting would bring an end to the war.

V-E Day found the Daredevils occupying Ulzen, Germany. They had been at the tip of the spearhead for 138 days of nearly constant combat, and it was now time to take stock. The death toll for the Daredevil tankers included 43 officers and enlisted men killed in action. They had also suffered an astonishing 57 tanks lost during their six months on the line.

On the positive side, Lt. Col. Rubel’s 740th Tank Battalion accounted for 69 enemy tanks destroyed, including 17 Tiger and Tiger IIs. The Daredevils also smashed or captured hundreds of cannon and combat vehicles. They even shot up 200 airplanes, most of them caught on the ground when the battalion overran an airfield at Hagenow.

Captain Berry, Lieutenant Powers, and Staff Sergeant Loopey each received a Silver Star for their actions at Stoumont. Every 740th tanker who fought there was awarded a Presidential Unit Citation. For many Daredevils, however, the best tribute to their heroism came from a tank commander named Cecil Taylor, who summed things up in 2008.

“We were a good outfit,” Taylor remarked. “I don’t know if it’s because we were scared or just didn’t have any better sense, but we got the job done.”

Brave Americans like Cecil Taylor turned the tide of battle, stopping Hitler’s elite SS at Stoumont.

To fill in some of the gaps you need to listen to Harry F Miller 740th TB interview https://www.youtube.com/watch?fbclid=IwAR0khnUeOALFZ59j390TqjVKI74_991haQP6d89K7z1aKej-fJBwAm51b8g&v=5iG0cUXFkSg&feature=youtu.be

For a good read, concerning the efforts of the maintenance people in the Armored Corps, check out; “Death Traps. The survival of an American Armored Division in WW2.” By Belton Y. Cooper https://www.penguinrandomhouse.com/books/31477/death-traps-by-belton-y-cooper/

https://www.bing.com/videos/search?q=death+traps+cooper&docid=608033778519203471&mid=FDE0446DB3E0974C2FD0FDE0446DB3E0974C2FD0&view=detail&FORM=VIRE

Fascinating. Revisionists historians and Nazi fanboys all over the web have been claiming for years now that US tank battalions encountered German Tigers on only two or three occasions and got their butts kicked in each, and that in all but these two or three incidents the US tankers misidentified Panzer Mark IVs they destroyed as Tigers. Kicking Kampfgruppe Peiper’s King Tiger-equipped butts like this puts the lie to the fanboys’ claims!

Mad Tom

Major, Armor, US Army (Retired)

My Dad, Elmer Tompkins was with the 740th from the beginning. Was at most of the major battles. We had a 740th reunion every year at either Dallas, or Oklahoma City. I was honored to have met almost all of the”Daredevils”, including George Ruble. Most of these men were just good ol’ country boys who Loved their country.many books have been written about the 740th. My personal favorite is “Into the Breach’ by Paul L. Pearson