By Michael D. Hull

German defenders hunkered in their concrete and steel bunkers along the Normandy coast were in for two major shocks on Tuesday, June 6, 1944.

The first came in the early morning hours of that fateful day when they peered out at the chill-gray English Channel and saw a powerful Allied armada of 5,000 ships standing offshore. The second shock came a few hours later when German coastal battery crews observed an amazing assortment of specialized tanks swarming across the beaches as Operation Overlord got into high gear.

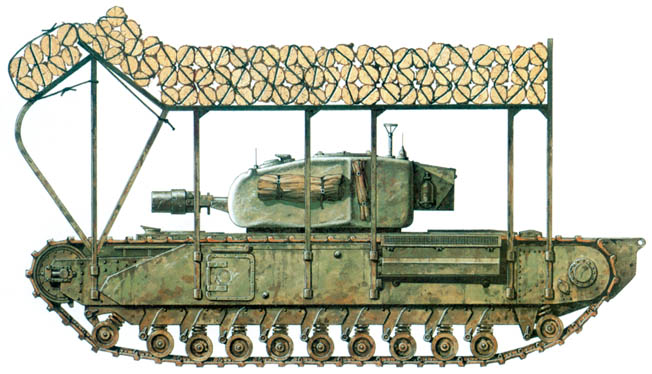

Some of the Allied tanks had giant rotating cylinders in front, which flailed the beaches with iron chains, detonating mines. Others carried large bundles of brushwood—fascines—in front, which they dropped into antitank ditches and then rolled across. Still other armored vehicles carried 30-foot bridging gear, or winched and towed disabled vehicles off the beach, or lobbed 40-pound projectiles—“flying dustbins”—at enemy gun emplacements. And there were many amphibious Sherman medium tanks wearing canvas skirts, emerging from the sea like futuristic monsters.

The bizarre collection of tracked vehicles, most of which were modifications of reliable, heavily armored Churchill tanks, belonged to the British Army’s 79th Armored Division, which had been established in 1943 on the orders of Field Marshal Sir Alan Brooke, chief of the Imperial General Staff. After the disastrous assault on the French port of Dieppe on August 19, 1942, Allied planners realized that any subsequent invasion of well-defended continental Europe would succeed only with considerable armored support for the infantry.

Designed by British engineers to swim ashore and clear beach obstacles under fire, the specialized armor provided inestimable support to the landing forces on D-Day, confounded the Germans, and made deep penetrations inland. Nicknamed “Hobart’s Funnies,” the vehicles were the brainchild of Major General Percy C.S. Hobart, a Royal Military College graduate, Bengal sapper, decorated World War I veteran, and interwar tank pioneer.

Sherman Funnies: The Crab and the “Donald Ducks”

The first “funny” tanks ashore on D-Day were the Sherman duplex-drive (DD) amphibians, nicknamed “Donald Ducks.” The American-built, 33-ton Sherman M-4 was fitted with twin propellers working off its main engine. A large canvas buoyancy screen was erected around the hull, giving it the appearance of a huge baby carriage. Once the tank hit the beach, the canvas was lowered and the Sherman operated in its normal fighting capacity. But the DDs proved vulnerable. With a freeboard of less than a foot, they could be swamped in choppy seas.

These were the only Funnies used by the American assault forces—to their cost—on D-Day. At Omaha Beach, where elements of the U.S. 1st and 29th Infantry Divisions were pinned down and barely managed to gain a toehold on the morning of June 6, most of the DDs were launched too far out. Because of heavy seas, only a few made it to shore. The 741st Tank battalion lost 27 out of its 29 tanks.

Early trials for the DD tanks were conducted in the Staines (Surrey) Reservoir near London. Many British soldiers were understandably apprehensive at the prospect of riding in floating tanks. Lance Corporal Patrick Hennessey of the 13th/18th Lancers said, “The notion that we would swim our tanks across the water was difficult for us to understand. A tank is a solid steel object, and very heavy. ‘Surely,’ we said, ‘it will sink like a stone?’ ‘Not so,’ said the boffins (military scientists), ‘consider this stone of which you speak. If you place it in a canvas bucket, and put that bucket into the water, it may go down an inch or two, but it will float.’”

Lieutenant W.D. Little of the Canadian Fort Garry Horse Regiment described the first DD tank he saw, soon to be issued to his unit: “This little barge turned and headed toward us, and as it rolled you could see it struck the bottom of the pond or lake, and started to roll up. Lo and behold, tracks! This was a tremendous surprise. Then as it rolled forward, the tracks kept coming higher; and then as it got to the edge of the water, down came the screen and there was the gun. This was a terrific surprise and shock.”

The Crab was a Sherman mounting a rotating roller with flails to clear mines from its path. Conceived by a South African officer and having proved its worth in the Battle of El Alamein, it could clear a gap 10 feet wide at a speed of 1.5 miles per hour and could also destroy barbed-wire obstacles. But it had to operate with another Crab in order to open a path at least two tanks wide.

The Churchill Assault Vehicle, Royal Engineers

The “Bobbin,” a special adaptation of the 39-ton Churchill tank, was designed to help armor traverse soft sand by laying a canvas or wire carpet from a roller on its front. The carpet was almost 10 feet wide and thus capable of supporting most military vehicles.

One Churchill AVRE (assault vehicle, Royal Engineers) was an armored ramp carrier, code-named ARK, adapted to carry a bridge that could be dropped over a 30-foot-wide gap in as many seconds. The equipment could also be used to surmount a 15-foot wall. In either case, the bridge could support 40 tons, sufficient for all but the heaviest of vehicles.

Other Churchill-based AVREs carried fascines to fill antitank ditches and craters, or spigot mortars firing petards (explosive-filled canisters) used against heavily fortified strongpoints. Some AVREs also mounted Snake, a four-inch, explosive-filled metal tube that could be fired 400 feet into a minefield to clear a lane for armor. The Crocodile, a conversion of the Churchill Mark VII, had a flame gun in place of the hull-mounted machine gun and towed a trailer carrying 400 gallons of fuel that was forced into the gun by compressed nitrogen. The Crocodile spewed a long tongue of flame that terrorized enemy soldiers. Although the German Army itself used flamethrowers widely, many of its officers and men considered the British Crocodile an unfair battlefield weapon. At a reunion of elite World War II airborne troops in Germany in 1990, veterans recalled that they had been so angry at the use of Crocodiles that they would have immediately executed their crews if they had fallen into their hands.

Specialized Armor on All Five Beaches

In addition to these Funnies, there was the BARV (beach armored recovery vehicle), a turretless tank with winches or small bulldozer blades for towing or pushing stranded vehicles off the beaches, and an armored version of the heavy-duty Caterpillar bulldozer that could perform a variety of tasks. And, before long, dozer-bladed Churchills and Shermans appeared for cutting brush and undergrowth, as in the Normandy bocage countryside.

The British, American, and Canadian Armies made wide use of two-and-a-half-ton DUKW (Duck) amphibious trucks for landing personnel and cargo at Normandy. Having already proved valuable in the Mediterranean theater, the Duck fulfilled the vital role of bridging the gap between landing craft and the dry shore. Other specialized armor included old British Crusader cruiser tanks mounting twin 20mm antiaircraft guns to provide protection from any aerial threat, and light British Tetrarch tanks that were dropped in specially designed Hamilcar gliders.

While the Americans were impressed with the amphibious DD Shermans, which were deployed on all five of the D-Day beaches, they rejected General Hobart’s specialized armor. His offer was turned down by Lt. Gen. Omar N. Bradley, commander of the U.S. First Army. One of his staff officers explained later, “The general didn’t like the Funnies. He saw it as an infantryman’s battle. Besides, the tanks were British. He thought we should do it on our own.” Bradley was not alone, and the other Americans failed to appreciate the potential value of the specialized armor. Given a chance to watch Hobart’s Funnies in practice runs, U.S. Army officers took one look and dismissed them as highly specialized variants of a basic weapon they considered effective purely as a mobile fortress.

Yet, the Funnies—particularly the flail tanks—proved invaluable to the invading British, Canadian, and Free French infantry and commandos on Sword, Gold, and Juno Beaches. On Sword Beach, British Army Captain A. Low watched one of his mine-clearing tank crews use its spinning flail to pulverize a German gun position. The Funnies would have made a big difference on Omaha Beach, where U.S. combat engineers gave their lives while defusing mines—at the time that mines were being harmlessly neutralized by flail tanks on the other beaches. Consequently, American progress through the German obstacles and off the beaches was markedly slower than that of the British forces.

Hobart’s Funnies demonstrated their worth dramatically on the Normandy beaches. Where they were used en masse in the forefront of the landings, success was achieved despite stiff enemy opposition. Deep penetrations—as many as six miles on the first day—were made inland. And in the days to come, during the slow, slogging struggle through the Normandy bocage, the 79th Armored Division’s specialized armor played crucial roles by adapting their characteristics to changing circumstances. From Normandy to Berlin, the AVREs and other Funnies constituted a formidable weapon in the liberation of Western Europe.

General Hobart’s Early Military Career

Bespectacled, owlish, and slightly built, Percy Cleghorn Stanley “Hobo” Hobart was a longtime and forceful advocate of mobile armored warfare—and one of the unsung heroes of World War II. An energetic, abrupt-mannered eccentric, he was regarded as highly suspicious by many of his straight-arrow fellow officers in the British Army. Some, including the courtly Sir John Dill, chief of the Imperial General Staff before Alanbrooke, saw him as a “loose cannon” who should be kept on a short leash. But that did not matter; Hobart was highly valued by another brilliant eccentric, Prime Minister Winston Churchill.

Hobart was born in India in 1885, the son of an Indian civil servant. He was educated at Clifton School and entered the Royal Military College at Woolwich at the age of 17. At the Shop, as Woolwich was known, he proved to be a moderate sportsman and captained the second rugby eleven. He was commissioned in the Royal Engineers in 1906, and joined the elite 1st Bengal Sappers and Miners Regiment in India. He served with the Mohmand Hills expedition on the North-West Frontier in 1908 and was on the staff of the Delhi Durbar in 1911.

Known as Patrick to his family, Hobart soldiered in France in World War I. He was in the thick of the action at Neuve Chapelle in March 1915 and was awarded the Military Cross for his courage and resourcefulness. He also took part in the engagements at Aubers Ridge that May and at Loos in September. Then he was shipped to the Middle East.

Hobart joined the staff of an Indian Army infantry brigade and went with it to Mesopotamia in 1916 to take part in an abortive attempt to relieve the besieged British garrison at Kut-al-Almara. He flew, became a specialist in aerial reconnaissance, was awarded the Distinguished Service Order in 1916, and was mentioned in dispatches six times. Hobart was promoted to brigade major and cited for his staff work during the British advance to Baghdad in 1917.

But he almost threw it all away by making an unauthorized reconnaissance flight along the River Euphrates in March 1918. The plane was shot down behind the Turkish lines, and Hobart and his pilot were captured. They were rescued by an armored car patrol sent more than 50 miles to find them. Hobart managed to avoid a court-martial for disobedience and was restored to his brigade in time to participate in General Edmund Allenby’s brilliant offensive against the Turks at Meggido in Palestine.

In the Interwar Armored Corps

Awarded the Order of the British Empire in 1919, Hobart attended the Staff College in Camberley, Surrey, and then returned to India and the North-West Frontier. While serving on the staff of Eastern Command in India, he became an ardent advocate of armored warfare. Taking a plunge that few officers with prospects were ready to consider, Hobart volunteered to join the newly formed Royal Tank Corps in 1923. He became an instructor at the Quetta Staff College in Baluchistan (now Pakistan), specializing in tank tactics.

During his 1923-1927 tour of duty there, Hobart corresponded with Colonel J.F.C. Fuller, Britain’s leading tank authority, and formulated clear concepts about future armor doctrine. Hobart gained a reputation at Quetta as both a brilliant trainer of troops and a seducer of women. After a scandalizing divorce case, he married the wife of one of his students. It was at this time that Hobart’s sister, Betty, married an up-and-coming officer, the future Field Marshal Bernard L. Montgomery.

After a short spell with an armored-car unit in India, Hobart returned to England to serve as second in command of the 4th Battalion of the Tank Corps at Catterick, Yorkshire, from 1927 to 1930. Promoted to colonel, he took command of the 2nd Battalion in 1931 and led it in revolutionary exercises on the rolling Salisbury Plain in Wiltshire. The British Army was pioneering mechanized warfare and battlefield radio use, and Hobart played a dynamic and inspiring role.

With the rank of brigadier, Hobart then served as inspector of the Royal Tank Corps in 1933-1936, during which time he founded and led the 1st Tank Brigade. The unit was in the forefront of armored-warfare development at the time when Nazi Germany was creating a secret panzer force and officers like Charles de Gaulle in France and Adna R. Chaffee, Dwight D. Eisenhower, and George S. Patton Jr. in America were experimenting with armored units. Hobart led the tank brigade with distinction and flair during crucial maneuvers in 1934 as the British Army improvised the world’s first armored division of all arms.

At a Royal Tank Corps dinner in 1935, Hobart met Churchill, who, as First Lord of the Admiralty, had named and helped to develop the world’s first tank in World War I. The two men formed a close association, and Hobart felt a “spiritual kinship” with the future prime minister. The general came to see Churchill as the savior of Great Britain. The following year, Hobart and Churchill met quietly to discuss armor development and the former’s frustration at the army’s emphasis on slow, heavily armored tanks rather than faster cruiser tanks.

Promoted to major general, Hobart served at the War Office and was appointed director of military training. By now, he was described as the army’s “most senior and experienced expert in mechanization” and was in an ideal position to promote his ideas. He believed that well-designed, capably handled tanks, without need of infantry support, would easily overcome enemy armor and infantry and revolutionize modern warfare. For this reason, the stubborn, single-minded Hobart clashed constantly with the cavalry and infantry generals and made enemies at all levels.

He was not easy to work with. Temperamentally unsuited to working as a team member, his impatience and lack of tact antagonized colleagues who might have proved useful to him. A confidential report described how “on various occasions in his military career, he has been reported as impatient, quick-tempered, hot-headed, intolerant, and inclined to see things as he wished them to be, instead of as they were.”

“Self-Opinionated and Lacking in Stability”

In mid-1938, the difficult Hobart was shunted off to a backwater posting, Egypt. There, in the face of Italian aggression in North Africa, he was ordered in an ill-defined brief to form armored units. Far removed from War Office infighting and the opposition of generals who failed to grasp the potential of armor, Hobart was in his element in the arid Egyptian desert. With energy and enthusiasm, and despite a lack of modern vehicles, he raised and trained a mobile force that became the 7th Armored Division, which fought the Italians and the Afrika Korps in 1941-1942 and gained fame as the first of the “Desert Rats.”

But Hobart’s efforts in the desert went unappreciated. His combative advocacy of armor had not endeared him to Sir John Dill (CIGS) and General Archibald P. Wavell, the Middle East commander in chief. Maj. Gen. Henry Maitland “Jumbo” Wilson, the Army commander in Egypt, reported adversely that Hobart was an officer whose “tactical ideas are based on the invincibility and invulnerability of the tank to the exclusion of the employment of other arms in correct proportion.” Wilson considered Hobart “self-opinionated and lacking in stability” and had a hand in removing him from command of the 7th Armored Division.

Creating an Armored Army

Wavell endorsed Wilson’s report and sent Hobart back to England in 1940. Appointed CB (Companion of the Bath), the feisty tank pioneer was ordered to retire and was effectively cashiered. Though disillusioned and embittered, Hobart was nevertheless determined to serve his country at the critical time when it stood alone against the Axis powers. So, at the age of 55, the general became a lance corporal with the Local Defense Volunteers detachment in his picturesque home village of Chipping Campden in Gloucestershire. He was later promoted to deputy area organizer. The LDV, a motley militia network of World War I veterans, youths, and men unfit for regular military service, was mobilized for defense when a German invasion of England seemed imminent after the fall of France in the late spring of 1940. It was later renamed the Home Guard.

Hobart put it about that he was appealing to King George VI to be reinstated in the army. Then, in August of that year, as the Battle of Britain was deciding the fate of Western freedom, the new prime minister, Winston Churchill, was shocked to read a newspaper story about how the nation’s leading armor expert was serving as a lowly NCO in the Home Guard.

Churchill was concerned about the poor state of Britain’s armored forces. With a few exceptions in the Battle of France and in the Western Desert, British tanks had not performed well. Few in number, they were undergunned and too often prone to mechanical breakdowns. The prime minister was looking for a man to place in supreme charge, one who would steer tank philosophy, design, and procurement and raise and train officers and men for armored units. The perceptive Churchill knew that the armored divisions that one day must liberate Europe would have to be at least a match for Adolf Hitler’s panzer formations.

But Churchill had an ingrained skepticism of his generals and doubted that there was anyone in the army with enough enthusiasm for the task. He sought advice from General Frederick A. Pile, the leader of Antiaircraft Command during the Battle of Britain. The amiable, unflappable Pile, himself a Tank Corps officer, reported later, “I told him we had a superb trainer of tanks in Hobart, but he had just been sacked. He asked me to get him to come and see him.” Pile approached Hobart, who resisted initially because he wanted his honor reinstated.

Eventually, Hobart answered Churchill’s summons and went to see him on October 13, 1940. The prime minister took his measure and sent a memorandum to the War Office stating, “I am not at all impressed by the prejudices against him in certain quarters. Such prejudices attach frequently to persons of strong personality and original view.”

Hobart, meanwhile, had wasted no time before Churchill rescued him from obscurity. He circulated to select generals in the Tank Corps his proposal for “an armoured Army.” He wanted to create wholly armored battle formations that were aggressive and “not tied to or clogged by infantry formations.” Hobart envisioned 10 armored divisions, with 10,000 tanks and a vast training program, led by a tank general who would have the full support of the Army Council.

But his demand far exceeded Britain’s industrial capacity in 1940-1941, so he settled on a task he knew well—building a tank unit from scratch. In March 1941, Hobart found himself GOC (general officer commanding) of the 11th Armored Division. He raised and trained it with characteristic vigor and purpose, though perceived as “merciless” in his methods. One officer observed that the only way a subordinate could earn Hobo’s respect was to “stand up to his bullying.” The 11th Armored Division was ready for service in 1942, but its commander was bitterly disappointed to learn that he was officially too old to lead it in the field. He was two years older than Montgomery and two years younger than Alanbrooke. Later that year, while recovering from an illness, Hobart sadly watched the division depart for Tunisia.

Specialized Tanks of the 79th Armored Division

That year he was transferred to take command of what would become the 79th Armored Division. But in March 1943, Brooke considered disbanding the division for lack of resources. However, this presented an opportunity to convert Hobart’s command into developing specialized armor that could be deployed to penetrate enemy concrete and steel obstacles during the planned Allied assault on mainland Europe. So, Brooke offered the leading role to the forceful armor innovator. After weighing the offer for a day, Hobart accepted the CIGS’s invitation, requesting that, as well as training the division, he be allowed to lead it in action, “which you seem so anxious to prevent me from doing.” The normally dour Brooke laughingly agreed. Thus, the CIGS ensured Hobo’s absolute loyalty.

Given a free rein to mold the 79th Armored Division and assemble its diverse phalanx of battlefield beasts, Hobo became a powerhouse of creative energy and inflexible determination. The division’s insignia was an inverted triangle with a ferocious bull’s head. Hobart started experiments in late July 1943 with British Valentine tanks, using a flotation device invented by Nicholas Straussler. Basic techniques were worked out during the year, and an Allied program was developed to train five British and two Canadian armored regiments, in addition to three U.S. tank battalions. A demonstration in January 1944 impressed General Dwight D. Eisenhower, the Allied supreme commander, and he directed that the amphibious DD tanks also be used to support the American assault divisions at Omaha and Utah Beaches during the planned invasion.

Meanwhile, noting that the Valentine tank was now obsolescent, General Hobart insisted that the flotation equipment be fitted to the Sherman, then the first-line tank in British and U.S. armored units. But he pointed out to Eisenhower that the limited industrial facilities then available could not produce enough DDs in time for the invasion, which was planned for May 1944. A British DD expert flew to the United States with a set of drawings, and the first 100 American-built DD tanks were shipped to Liverpool within six weeks.

As Hobart, under a cloak of secrecy, shaped the 79th Armored Division into a formidable and unique force, his enthusiasm fired the staffers and units. As each problem was discovered in the course of a long series of experiments and trials, Hobart led the way in seeking solutions and badgering the War Office and the Ministry of Supply to meet his demands. By the end of 1943, most of the major problems had been resolved, and the complex Operation Overlord blueprint was taking shape.

Hobart’s brother-in-law, Montgomery, championed the 79th Armored Division, and Hobart himself sat in on many conferences with highranking British, American, and Canadian generals, trying to sell the diverse mechanical beasts in what some called his Noah’s Ark. When General Eisenhower made his bold decision for the Normandy invasion to “go” on June 6, despite a marginal weather forecast, Hobart was on hand to hear it and offer advice to Monty, the ground forces commander.

1,900 Funnies Land in Europe

General Hobart and his lumbering Funnies spearheaded the historic Allied landings, with complete success achieved despite fierce German opposition. Deep penetrations were made inland, and the division—ultimately numbering 1,900 vehicles—rolled eastward toward Berlin with the liberation juggernaut. Units of the 79th Division pushed from Normandy; took part in the clearing of Brest, the English Channel ports, and the Scheldt estuary; fought in the bitter Reichswald campaign; crossed the River Rhine; and took part in the British armies’ final pursuit to the Baltic Sea.

Hobart was always in the thick of the action, dashing between his headquarters, Montgomery’s mobile command posts, and the leading formations. Sometimes, as around Boulogne, he was personally involved in the fighting. Inexhaustible, Hobart visited his troops before and after action—learning from them, encouraging them, and remorselessly firing those who failed to meet his standards. He bristled when some of the division’s elements were put to use in “penny packet” operations. The final use of DD tanks in northwest Europe came on April 29, 1945, when a squadron of the Staffordshire Yeomanry crossed the River Elbe.

Hobart’s brief but action-filled combat career in World War II was climaxed on March 26, 1945, when he rode one of his Buffalo amphibious carriers across the Rhine accompanied by Churchill, Alanbrooke, Montgomery, and General Miles “Bimbo” Dempsey, commander of the British Second Army. By this time, the 79th Armored Division had a strength of 21,000 officers and men and 1,566 tracked vehicles. There were 14,000 men and 350 armored fighting vehicles in a normal armored division.

Crucial Weapons on the D-Day Beaches

Although his fellow countrymen had spurned the offer of Hobart’s Funnies, General Eisenhower paid tribute to his contribution: “The comparatively light casualties which we sustained on all the beaches except Omaha were in large measure due to the success of the novel mechanical contrivances which were employed…. It is doubtful if the assault forces could have firmly established themselves without the assistance of these weapons.”

Monty wrote later, “The division is composed of units and equipment which have no parallel in any other army in the world, and the skillful use of this equipment enabled us to obtain surprise in the tactical battle.”

Sir Basil Liddell Hart, the famous military theorist, described Hobart’s Funnies as the “tactical key to victory,” while Nigel Duncan said in his book about the division, “Inspired by its divisional commander, it pursued its way with gaiety tempered with the resolution to be defeated by no difficulty whether of Nature’s or man’s creation.”

The 79th Armored Division was broken up at the end of the war, and Hobart retired in 1946 and was appointed commandant of the Specialized Armored Experimental Establishment. He was knighted, acted as a military adviser to the Nuffield Organization, and sought—unsuccessfully—to be installed as a professor of modern history at Oxford University despite the sponsorship of Churchill, Alanbrooke, and Montgomery.

Hobart also served as colonel-commandant of the Royal Tank Regiment in 1948-1951 and lieutenant governor of the Royal Chelsea (Veterans) Hospital in 1948-1953. Diagnosed with cancer in 1955, the unsung hero of D-Day died on February 19, 1957, fiercely combative to the end.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments