By Kelly Bell

On Sunday, September 10, 1944, all bridges over the German-Belgian border rivers, the Our and the Saur, were dynamited. Word circulated throughout western Germany that the Americans were coming. In some cases the battered remnants of German divisions were not given time to reach the eastern banks before the bridges were blown.

The Americans were closing in so quickly that any hesitation was thought foolish. Remaining occupants of the small towns dotting the rivers’ eastern shores were busy hauling in the final harvest before the ground war arrived. These residents were also burying valuables and nonperishable foodstocks while watching the streams of ox cart-drawn refugees flow back into the Fatherland. These once proud and haughty “settlers” had confidently followed the onrushing German Wehrmacht four years earlier as it stampeded to overwhelm Western Europe. Now they deserted their usurped holdings as the liberators from overseas bludgeoned their way ever closer.

The Allied bomber fleets swelled daily as they grumbled endlessly overhead. The big birds’ escort fighters habitually plunged from the heights to strafe whatever they caught in their crosshairs—soldiers, civilians, vehicles, trains, even livestock. The Americans were coming, and if the foot soldiers were anywhere near as bloodthirsty as their pilot comrades seemed to be, there was plenty to fear.

The women, children, and elderly in the border towns had no one to protect them. The young men were long gone, consumed mainly by the faraway Eastern Front. A few crippled POWs the Allies had returned told of limitless reservoirs of manpower and matériel, of supply and weapons depots so vast one could get lost in them, and how this was pouring into Europe from cargo fleets that stretched beyond the Atlantic Ocean’s western horizon. These reports were not the only ominous signs.

Most residents of the frontier river region heeded Berlin’s order to evacuate the immediate vicinity. Hannalore Weiss-Thomas was 12 years old at the time and recalled later, “From up on the heights above our village of Gmund we could see something moving among the trees on the Luxembourg bank and hear the noise of their vehicles on the roads beyond. I remember well how I burst into tears when my mother showed them to me just before we fled. They were the dread Amis, come to do … I didn’t know what.

“I little realized that 10 years later I would be married to one of them and living in Chicago, but then I was frightened. Awfully frightened. Now I know, of course, that on that Monday the world was about to change. Not only my own little world, but the world of everyone in Europe … for the rest of the 20th century.”

On the evening of September 11, a five-man patrol of General Courtney Hodges’ U.S. First Army waded across the Our and warily ventured into Germany. Sergeant Warner W. Holzinger, Corporal Ralph Diven, T/5 Coy Locke, Pfc. George McNeal, and a French lieutenant named Lille serving as an interpreter sloshed across the stream and found themselves in the middle of the famed Siegfried Line. They cautiously investigated one pillbox after another. All were empty. The floors were coated in dust, and local farmers had converted some into chicken coops. The defenders had been sucked away by the manpower drain of the Eastern Front.

A deserted Siegfried Line was infinitely more than the invaders had dared hope for, and within the hour Hodges was informed of the apparent windfall. Holzinger was the first armed foreign soldier to set foot in Germany by force of arms since 1814.

There was obvious cause for optimism among the Allies. The Germans had been cleared from France and their other Western conquests in a late summer sweep so swift that these first steps in Germany had come a full 233 days ahead of the pre-invasion timetable. Looming in front of Hodges’ army, however, was a barrier even more formidable than the Siegfried Line, and this one was manned.

It was a dark and brooding forest, the Hürtgen, straight out of Grimms’ fairy tales. While there were no ogres, trolls, or witches creeping through its gloomy confines, these 50 square miles of towering timber harbored a series of bristling, well-camouflaged fortifications. When American troops eased into the woods they found a defense system untouched on the Western Front, one that would dish out the worst defeat Allied ground forces would suffer in Europe.

Facing Formidable Defenses in the Hürtgen Forest

After breaking out of their Normandy beachhead, the Allies had romped across France with such speed they overextended their supply lines. Supreme Commander General Dwight D. Eisenhower ordered his generals to ration their supplies until the situation could be stabilized. One of Hodges’ subordinates, Maj. Gen. Joe Collins, had other ideas.

“Lightning Joe” Collins was 48 years old but looked much younger. He had won his moniker via his brilliant handling of the 25th Infantry Division against the Japanese at Guadalcanal. Now commanding the First Army’s VII Corps he believed all that was needed to send the Wehrmacht to the surrender table was for him to lead his men through the remaining defenders to the last natural barrier to victory, the Rhine River.

“Don’t stop men when they’re moving!” Collins pleaded to Hodges. He proposed that his troops be allowed to bypass the German city of Aachen and its defenses, breach the Siegfried Line immediately so the enemy could not man it at the last moment, then pause to await the supply convoys. Hodges eventually relented and allowed his impatient corps commander to go ahead with his “reconnaissance in force,” but to halt if he encountered substantial opposition and await supplies and reinforcements.

Collins had no intention of following these orders to the letter. He aimed to develop his probe into a major offensive and saddle Hodges with the responsibility of keeping VII Corps supplied.

Lightning Joe did not take the looming woods lightly. He had read of General John J. Pershing’s problems in the Argonne Forest 26 years earlier. These woods lay on very rough terrain whose heights soared to 1,000 feet and were bisected by fast-flowing streams and narrow canyons. Embedded in the craggy slopes were scores of pillboxes and bunkers whose interlocking fields of fire passed over rows of dragon’s teeth, concrete tank obstacles. These innocuous looking concrete stumps were everywhere, effectively blocking passage to any kind of tracked vehicle.

There were also thickly strewn fields of plastic Schu mines, invisible to metal detectors, and the feared Bouncing Betty mine. This simple explosive sprayed a canister of metal balls at waist height.

Collins sent part of his command into this hornets’ nest to guard his right flank from counterattack. It was a pointless move. The Nazis in the forest were set up exclusively for defense and had no thoughts of attacking. All the Allies needed to do was bypass and encircle the woodlands and starve the Germans into surrender. The Western Front would have been breached and the war possibly won by Christmas.

Not one top-ranking U.S. Army commander in Europe appears to have thought of this logical, humane strategy. Instead, divisions would be fed into the deadly defenses at a rate of about one every other week. As fresh forces arrived they would stare in bewilderment at the few savaged survivors stumbling shell-shocked to the rear, victims of a meaningless offensive whose contribution to final victory was negligible. The folks back in the States expected to read headlines of more smashing battlefield triumphs in Europe. The war correspondents gave them just that and omitted the ugly reality of the Hürtgen Forest.

First Assault on the Forest

On September 13, the 9th Infantry Division was the first to enter the treeline. By the 17th, its men were fighting for their lives as the defensive emplacements and artillery to the east mauled them. The invaders were also bedeviled by fast-moving patrols of young German soldiers fighting on familiar ground.

These opening actions were pretty much a draw until the 22nd, when the Nazis opened up with 17 150mm howitzers, nine 105mm howitzers, an undetermined number of 120mm and 80mm mortars, and a few 210mm cannons. For 15 minutes terrified Americans huddled in their muddy foxholes amid the explosions. Plate-sized slabs of glowing shrapnel slashed mature trees in two, and tons of soggy earth blown skyward rained back onto the soldiers, forcing them to dig their way out like moles.

When the barrage abruptly stopped it was supplanted by shrill signals from officers’ whistles, shouts in German, and the clatter of tank tracks. The Nazis did well at first, overrunning the U.S. right flank and capturing a cannon company’s howitzers. Just in time, divisional commander General Louis Craig sent in his 746th Tank Battalion and 899th Tank Destroyer Battalion. The Germans retreated to their pillboxes, but their artillery again opened fire. The path through the trees was already getting bloody.

Woodland combat was new to the invaders, so the best methods of neutralizing the pillboxes had to be learned in action. The 9th Infantry Division had fought through North Africa, Sicily, and France. By the end of September, it had taken more casualties in the Hürtgen Forest than in all its earlier World War II engagements combined. With the defenses seemingly growing stronger by the hour, the 9th was pulled out for a rest.

After this repulse one embittered survivor groused, “If anyone says he knew where he was in the forest, then he’s a liar!” The Germans seemed to be everywhere, and their artillery strategy was yet another unfamiliar menace as a foxhole became a death pit unless it had a stout covering. Nazi gunners aimed their artillery not at American positions, but at the trees above them. Striking the trunks, the shells showered hapless GIs with hot, jagged shrapnel. The inclination to drop flat or huddle in a hole were the worst possible reactions because they exposed a man’s entire body to the downward-hurtling fragments. The safest response was to snap to attention, but few were aware of this and continued to do as instructors had taught them.

Any kind of movement at night was almost suicidal. With both sides terrified of the dark, it took little sound or imagination to prompt a burst of gunfire. Opposing positions were often separated by only a few yards, and in the blackness men shot first and identified targets at dawn. Soldiers crouched motionless in their foxholes wishing wildly for the murky daybreak, and the nights were getting longer.

High Command Ignorance

For a time the Allies attempted to evacuate their dead and wounded during the lengthy nights, but both sides’ trigger happiness made this impractical. Short cease-fires were granted so injured men could be carried to safety, but sometimes this was not enough. Late in the campaign General James Gavin of the 82nd Airborne Division was horrified to stumble across an aid station that had apparently been abandoned in the heat of battle and the wounded left to die. Gavin later described the sight of “dozens of litter cases, the bodies long dead. In the midst of the fighting it had been abandoned, many of the men dying on their stretchers.”

Craig was usually scrupulous about his men’s welfare. He allowed his soldiers to write to inform him of their problems, the most legitimate of which he passed on to Eisenhower. He had seen what was happening in the forest, how the attackers were being savaged by Germans who were at home among the trees. Yet when Eisenhower informed Craig that the 9th was to attack again on October 2, Craig raised not one word of protest. He obediently sent his dazed survivors and fresh-faced replacements back into the Hürtgen where nothing had changed.

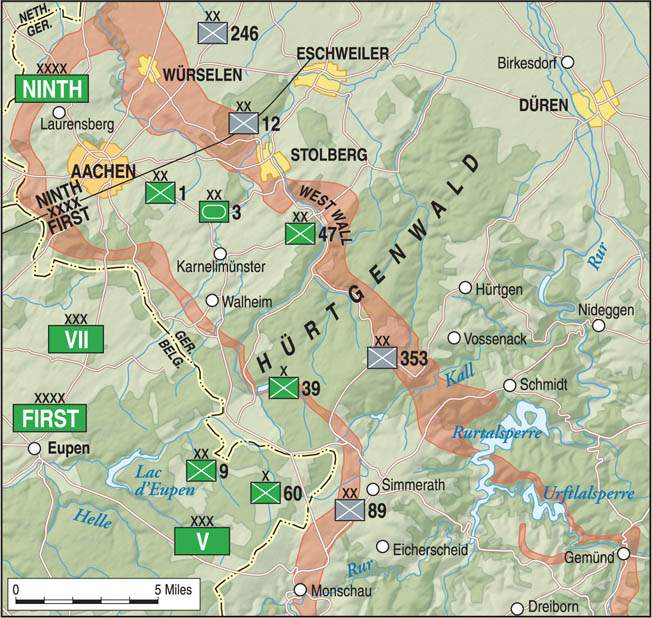

The primary targets were the towns of Germeter and Vossenack via a southward thrust over high ground past the Germeter-Hürtgen road and through the forest with the securing of the Schmidt-Steckenborn ridge the ultimate objective. As outlined on maps, the new assault looked too simple and logical to fail. The 9th Infantry Division’s 60th Regiment would advance to the left of the 39th Regiment into the woods and clear a three-mile-wide corridor while the 47th Regiment rolled up the left flank, securing it with 24-hour patrols and providing additional troops to the 60th and 39th if necessary. Nobody considered this latter possibility likely. No emergencies were foreseen.

The high command still had not grasped the realities of forest fighting. Supplying the regimental sectors across the pair of slender, easily blocked trails, which were all that was available for transport, would be impossible. Tanks could not penetrate the trees, which grew in such a dense mass that their branches interlocked. Even if the infantry reached open ground, the enemy would hold the next in the ongoing series of ridges, and the Americans would be unable to advance without tank support.

Worst of all, the brass had not taken into account how spotty control and communications between Allied units and their commanders would become once the attackers entered the forest. The trees were so thick it was virtually impossible for units to remain in mutual contact, so coordination in battle was out of the question. Small squads found themselves isolated and uncertain of their locations.

Second Assault on the German Positions

On October 2, right on schedule, the 9th Division trudged in during a downpour and relieved the 4th Cavalry Group, which had been manning the outer ring of Allied positions. German heavy machine guns firing up to 1,000 rounds per minute were already snarling at the wary Americans.

It took a while, but by daybreak on the 6th, Craig’s men were in position. It was never completely light under the thick tree canopy, especially beneath the overcast northern European sky, but on this morning the clouds parted and the sun slowly burned off drifting fog. Republic P-47 Thunderbolt fighter bombers screamed down to assault the Germans, spraying tons of .50-caliber bullets and dropping one 500-pound bomb per plane. Seven squadrons, 84 planes in all, hit the pillboxes, preceding an artillery bombardment with every heavy gun in the 9th Division.

The shells fell in a three-minute onslaught so violent it dazed even the Americans. After this first pounding there was a five-minute pause, after which the gunners opened up again in hopes of catching the Germans digging their way out of their half-buried positions. For two more minutes the long barrels belched. When they stopped, U.S. officers rose and bellowed the ancient order, “Follow me!” Six thousand scared young men heaved themselves from their muddy holes at precisely 11:30 am in the second major attack into the forest.

The lesson the Allies should have learned the previous winter and spring at Monte Cassino was bloodily repeated. Artillery bombardment of strongly fortified, reinforced positions is not particularly effective. The soldiers of the German 942nd Infantry Regiment and 257th Fusilier Battalion opened the slits in their undamaged pillboxes and poked machine-gun muzzles through the openings as the Americans, slowed by the densely packed trees, came into view.

To the northeast, the 39th was stunned by the volume of fire coming from the unseen strongholds, mowing down the vanguard and forcing survivors to drop flat despite their noncoms’ and officers’ hysterical commands to keep moving. Steadily the shouts of “Forward!” were supplanted by cries of “Medic!”

At first the 60th moved at a steady pace, but when its 2nd Battalion got within 1,000 yards of its objective it came under withering small-arms fire. Then came the sound the footsloggers had come to dread in Normandy, the mournful wail of the Nazis’ “Moaning Minnie” multiple barreled mortars commenced. As the bombs detonated in the soft, wet earth they sent razor-sharp steel and showers of scalding mud in all directions. The 60th’s 1st Battalion tried to keep going but blundered into a barbed wire-festooned minefield. Some men got hung up on the wire and were killed by the machine guns, while others had their lower bodies ripped apart by mines.

The 3rd Battalion hurriedly launched itself at the enemy in an attempt to dilute the pressure on the 39th and 60th, but the Germans had plenty of firepower for these newcomers. As the American generals in their faraway chateaus received the first reports from the grisly combat zone they realized their optimism had been false. Another mass movement into the Hürtgen was being crushed. Collins’ and Craig’s units were cut to pieces without having seen a single German soldier.

Walther Model’s Kampfgruppe Wegelein

The defenders were commanded by Field Marshal Walther Model, a 53-year-old career officer with no interest in politics apart from his ardent devotion to Hitler. After a painful tour of duty in World War I during which he was twice critically wounded, Model had no tolerance for excuses or explanations. During a highly successful stint on the Eastern Front he earned the nickname “the Führer’s Fireman” for his skill in stabilizing precarious situations.

With no skills apart from soldiering, Model was lost in peacetime, and this coupled with how the Soviets had branded him a war criminal to be hanged after Germany’s surrender incited him to throw himself into his new assignment in the West. Model had already humiliated British Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery by using two decimated SS divisions to defeat the British 1st Airborne Division at Arnhem, Holland, during Operation Market-Garden.

Now, Model sent for Kampfgruppe (battle group) Wegelein, named for its commander, Colonel Wolfgang Wegelein. As one of the few reserves left in the reeling Reich this outfit was an invaluable commodity to be used with extreme consideration. These 2,000 men were mostly officer cadets and among the finest soldiers remaining in the German Army. Throwing them against a well-armed, numerically superior enemy force was an undertaking of extreme implications, but Model had little to lose.

No Withdrawal From Hürtgen

By this time high-ranking American commanders were being fired. The 9th Division’s assistant divisional commander, the 60th Regiment’s commanding colonel, and the divisional chief of staff had all been sacked. A well-seasoned, 30-year-old colonel who had served with distinction in North Africa, Sicily, and Normandy replaced the latter. His name was William Westmoreland, who a quarter century later commanded all U.S. troops in Vietnam.

With so much not going according to plan, U.S. Army Chief of Staff General George C. Marshall flew across the Atlantic and traveled all the way to Craig’s headquarters to demand a full account of the unhappy situation. Realizing his and the Army’s reputations were at stake, Marshall made it clear there was to be no withdrawal from the Hürtgen and that no mention of what was happening there need be made to the press. The U.S. Army was to take the Hürtgen Forest by force of arms.

Dawn came quietly on Columbus Day, 1944, and briefly the American troops wondered if they might have an easy day, but as full daylight arrived there came the first moanings of the hated multiple mortars as another bloodletting commenced. For a few minutes the same old jarring explosions killed, maimed, and stunned young men in their foxholes. The barrage knocked out communications and several field artillery emplacements, but the real surprise came right after the shelling stopped.

From deep within the forest came muffled shouts and commands in German and the shrill warbling of officers’ whistles. Americans raised their heads and widened their bloodshot eyes at the sight of camouflaged cadets swarming toward them as Kampfgruppe Wegelein sallied forth to counterattack.

As the Germans overwhelmed the first depleted battalion of the 39th Regiment, its commander, Lt. Col. Van H. Bond, instantly realized they were trying to cut off and annihilate the 3rd Battalion, so he had his men execute the confusing maneuver of turning 180 degrees and attacking backward. If the 3rd went under, the other U.S. units might panic and break, and with few reserves available in the immediate vicinity this would be a disaster. All day the men of the 3rd did their best to hold the sagging lines, but the Germans were steadily gaining ground. As they reached the Germeter Road it seemed they were on the brink of hurling the 9th Infantry Division completely out of the forest, but incredibly the Nazis halted their advance at this point. It was later revealed that German communications were spotty and they had mistakenly been ordered to stop. They had also lost their bearings and were uncertain if they were advancing in the right direction.

Bond intended to launch a counterthrust of his own the next day, Friday the 13th. Wegelein had been ordered to withdraw to his defensive positions. Preparing to start back at dawn he was shocked when Bond’s men came at him and his cadets, who had taken about 500 casualties themselves the previous day. The weakened antagonists tore destructively at each other until Wegelein did something inexplicable.

During a lull in the fighting the elderly German colonel, his adjutant and German Shepherd in tow, strolled in the open right up to the front lines where an American sergeant quickly shot him dead. Perhaps this career officer who had been in the German Army since 1921 succumbed to despondency and decided to end it all by letting his enemy kill him. Whatever his motives, his death disheartened his young charges. They crept back to their concrete strongholds without firing another shot.

“If a Rifleman Lasted Three Days He Was a Veteran”

With the counterattack over, the stalemate resumed as the Allies continued to probe the German defenses. Staff Sergeant Kin Shogren recalled decades later how after Kampfgruppe Wegelein pulled back the Americans still lost “between one-quarter and one-third of our troops each day, so that there was a constant turnover of company personnel. If a rifleman lasted three days he was a veteran.”

By now winter was closing in, and men were coming down with frostbite and the agonizing malady of trench foot, which had tormented their fathers in World War I. After soldiers crouched for days in freezing mire their feet would begin to hurt so severely they could not walk. Removing their warterlogged boots and socks they would find their feet wrinkled, swollen, and a sickly shade of gray. Medics would peel away the dead outer layer of flesh in strips. The feet would then swell until they resembled grotesque red balloons, and they burned as if immersed in battery acid. Some men had to have their feet amputated. Exacerbated by malnutrition, the noncombat casualty situation was becoming serious. The 9th Infantry Division was reaching the end of its tether.

On October 24, the unit was informed it was to be sent to Belgium for rest and reinforcement. Since September the division had gained 3,000 yards through the forest at a cost of 3,836 casualties. A man had been killed or crippled for every two feet advanced, but the high command cleverly included the 47th Infantry Regiment in the casualty lists. The 47th had not been heavily involved in the fighting and suffered few losses. This enabled the brass to report a mere 30 percent killed or wounded.

Now plodding into the meat grinder was the 28th Infantry Division, which had originally been organized as a branch of the Pennsylvania National Guard. It was the first ever National Guard outfit, having fought in every one of its country’s conflicts since the Revolutionary War. It was commanded by General Norman “Dutch” Cota, who had won a Silver Star and Distinguished Service Order for his exploits on Normandy’s Omaha Beach where, as assistant divisional commander, he had shouted at a battalion of pinned-down Rangers, “You men are Rangers! I know you won’t let me down!” Later in the same campaign he earned a Purple Heart and another Silver Star.

Dutch Cota’s Impossible Orders

Cota’s command was assigned to capture the town of Schmidt to secure the right flank of Collins’ VII Corps advance on the Rhine. Whoever held Schmidt would also control the road network. The 28th was supposed to take the town by November 5, far too little time to both relieve the 9th and then plan and execute strategy for the attack. Cota pointed out these problems to Hodges along with the anticipated difficulties of advancing over rough, wooded terrain facing enemy-controlled high ground. When Hodges responded to Cota’s observations with icy silence, Cota shrugged and went to take on his impossible mission.

The 5th Armored Division would assist the 28th. The foot soldiers were to follow the same route as earlier advances, through Germeter, Vossenack, over the Kall River gorge to Kommerscheidt, and into Schmidt.

Cota’s superiors had made nearly all his command decisions in advance, leaving him with little freedom of action. He had to send his men over three lofty, German-occupied ridges and hope the Kall Trail (connecting Germeter and Vossenack) would give tanks access to the fighting. Occasional farm carts had worn this slender trace through the trees, and the assumption that it could accommodate Sherman tanks was brazen.

On Halloween, Hodges instructed Cota to attack on November 2, despite miserable weather. For several days a steady, freezing rain had saturated the sector, which was also shrouded in dense fog that ruled out air support and made artillery backup risky because of the danger that Americans would be shelled by their own guns.

Taking Schmidt and Kommerscheidt

At 8 am, 12,000 artillery rounds shook the rain-drenched, misty landscape as gunners opened up on what they hoped were the enemy’s positions. Following the bombardment the Germans manned their gun ports and waited, but the Americans did not come. They were awaiting a P-47 strike which they did not know had been postponed because of the weather. When the planes finally appeared that afternoon they mistakenly strafed a U.S. artillery position, killing or wounding 24 men.

At 9 am, the 28th began to cautiously filter through the trees, and at first things seemed to be going well as the 112th Infantry Regiment quickly captured Vossenack. Elsewhere, however, the situation was typically bloody. The 110th Infantry Regiment was mauled by the omnipresent German mortars and machine guns. With gaping holes ripped in their ranks, the survivors retreated.

Surprisingly, the next day brought good news as the 28th captured Kommerscheidt. Elsewhere, the 112th Infantry Regiment, shielded by a rain of shells from distant Sherman tanks, splashed across the freezing Kall, poured into Schmidt, and quickly overwhelmed the German garrison. They immediately commenced fortifying their new positions for the anticipated counterattack.

While the 112th was consolidating its hold on Schmidt, a row of Shermans eased along the Kall Trail. The track steadily narrowed until the lead tank was forced to stop to avoid falling off the path’s left side, down the steep gradient, and into the gorge. Darkness was gathering as engineers went to work shoring up the crumbling cart track, and as they toiled through the freezing night enemy artillery took repeated potshots at the line of stationary tanks but did not score any hits.

At 5 am on November 4, the priceless tanks gingerly resumed their advance, but the lead Sherman hit a Teller mine that ripped off a tread. The crew of the next tank attempted to go around the immobilized one but bogged down in the mud. Three Shermans finally made it into Kommerscheidt, their crews unaware that no additional rolling armor was detailed to support them. When the counterattack came, the three tanks would face it alone.

The American Retreat

At daybreak on the 5th, the Germans opened up on Schmidt with a cannonade. After a sleepless night the men of the 112th caught glimpses of hostile infantry darting between patches of cover or following behind 15 supporting tanks. The German tanks ignored the antipersonnel mines the Americans had planted during the night and the bazooka rockets that ricocheted harmlessly off their sloping sides. One after another U.S. units succumbed to panic and took flight. The unnerved Allies abandoned their wounded and galloped in terror back down the Kall Trail or into the trees, where Nazi infantry captured them.

The situation back at 28th Division headquarters became increasingly confused as reports of the mass flight began to arrive. Cota dispatched one of his colonels to investigate, but the man drove his jeep into a German patrol and was captured. The scene at Kommerscheidt was almost as chaotic.

As fear-crazed men from Schmidt poured into town their state of mind was contagious. Bellowing officers with cocked .45s tried to stem the stamped but managed to corral just 200 of the retreating troops to add to Kommerscheidt’s defenses, which included the three Shermans.

The first tank to challenge the oncoming Germans was commanded by Lieutenant Raymond Flieg, who recklessly charged at the enemy. The first German tank, a Mark IV, went up like a volcano as Flieg’s gunner hit it squarely with a 75mm shell. Next came a Panther. Undaunted, Flieg hurled two high-explosive rounds into its front, causing the tank to shudder but doing little damage. However, the rookie German crew panicked and abandoned the tank. Flieg destroyed three more German tanks to bring the armored thrust to a halt. It was the Americans’ sole ray of sunshine that dreary Saturday.

The U.S. 2nd Infantry Battalion, dug in on Vossenack Ridge, broke and retreated in disorder after being shelled at daybreak on the 7th. A few of the 2nd’s men remained in Vossenack, and Cota frantically cast about for replacements to send there. He came up with an engineer battalion and 70 slightly injured troops from a field hospital at Germeter. Led by a bleeding lieutenant, these walking wounded set out on foot for Vossenack. Most deserted en route.

That afternoon the fight over the town commenced in a drenching downpour, and luckily for the exhausted, undermanned U.S. units their opponents, elements of the 116th Panzer Division were also worn out and depleted. At nightfall the fighting fizzled as both sides ignored their dead and wounded and searched for some kind of shelter.

Securing a Limited Withdrawal From High Command

By now Cota realized his invasion of the Hürtgen Forest was doomed, but he was also aware of how fond General Bradley was of boasting how the U.S. Army never lost ground it “had bought with its own blood.” The Army had spilled much more of its blood in losing Kommerscheidt, Schmidt, and Vossenack than it had in momentarily winning them, and with a reduced number of hungry and demoralized soldiers there was no chance of retaking the towns. Cota decided to go ahead with the retreat that he realized was his sole civilized option, knowing how appalled Eisenhower, Hodges, and Bradley would be when they heard.

Extracting his men and equipment would be difficult under any circumstances, especially with the Kall Trail under enemy control. First came the Herculean task of obtaining authorization.

In a face-to-face confrontation with Hodges, Cota secured permission to execute a limited withdrawal across the Kall River. There would be no retreat from the Vossenack sector, and the 28th was to send troops to aid in planned assaults on the towns of Hürtgen and Monschau. Cota obediently acquiesced, condemning his soldiers to another week of death and agony.

On Wednesday, November 8, beneath another freezing cloudburst, the tattered remnants of the 110th and 112th Infantry Regiments commenced quietly picking their way to the rear, hoping the Germans would not notice the evacuation. As American artillery dropped a covering barrage, 350 remaining GIs disabled what operational equipment they still possessed. Then, each man, holding onto the shoulder of the one in front of him, set out in a long queue for the rear. The file was led by a colonel who immediately lost his way. When the Nazis started lobbing mortar rounds at the pathetic column, the men panicked and bolted. Miraculously, most managed to reach friendly lines.

The units earmarked for the twin offensive against Hürtgen and Monschau were given just 500 fresh replacements. In killing cold, battalions of the 110th were ordered to assist the 12th Infantry Regiment, 4th Division in its drive on Monschau and the wooded high ground overlooking Hürtgen. The temperature dropped so drastically that two signalmen froze to death when they went to repair a phone line the night before the attack.

The 110th was also to help assault a row of pillboxes outside the town of Raffelsbrand, and it was the same old story. For five days the infantry bled while trying to subdue the line of bristling bunkers. The 1st Battalion lost all but 57 of its 870 troops, and other units suffered almost as badly. On the 10th, the 116th’s Panzers returned and tore into the 12th Infantry Regiment. The following dawn brought a dense fog that hid surviving Americans as they slipped through enemy lines and escaped. During this last engagement, the 12th lost 1,600 men.

This was the last time the 28th Division would see action in the Hürtgen Forest. Its 112th Infantry Regiment alone had absorbed 167 killed, 719 wounded, 431 missing, 232 captured, and 544 noncombat (nearly all of them weather related) losses, leaving 107 somewhat healthy men out of the 3,000 who had gone into action two weeks earlier.

Fighting For the U.S. Army’s Reputation

Even now the Allied high command remained determined to root the enemy from the Hürtgen. The reputation of the U.S. Army meant literally everything. One hundred thousand of America’s finest would pour into the dreary forest in an effort to dislodge the Nazis through sheer force of numbers.

Hodges planned to use two complete corps in this fourth incursion. General Leonard T. Gerow’s V Corps would go in from the south while Collins’ VII Corps was to enter the northern sector. With the 4th and 8th Infantry Divisions and 5th Armored Division slated to attack directly into the forest, the coming invasion would be on a front 30 miles wide. Hopes and prayers were pinned on Allied air support. As usual, it was raining.

Bradley twice postponed the attack, hoping for a break in the weather. He hoped that with the assistance of his massive aerial armada the enemy could finally be overwhelmed and his troops “could push through to the Rhine in a matter of days.”

On the morning of November 16, the overcast parted. At 11:30 am, 1,191 Boeing B-17 Flying Fortresses of the U.S. Eighth Air Force dumped 4,000 tons of fragmentation bombs on the ruins of Schmidt. Then, 1,188 British Royal Air Force Avro Lancasters savaged the towns of Duren, Heinsberg, and Julich while Allied artillery opened its latest deluge of preparatory shelling. The Ninth Air Force came next with its heavy bombers and 1,000 fighter bombers to splatter the German defenses with yet more fragmentation explosives and millions of .50-caliber rounds.

As the last aircraft droned off to the west, American infantry charged into the damp, smoking landscape. Most expected little resistance after such an opening firestorm, and their generals tended to agree. By then they should have known better. To the rear, war correspondent Ernest Hemingway felt a dark foreboding as he watched the mass of young men head for the trees.

German machine guns began firing as soon as the Americans came into range, ripping gaping holes in the wavering ranks. The Nazis refused quarter to men whose helmets were emblazoned with large red crosses or small white ones. Medics and chaplains were killed as readily as their comrades.

The Germans were steadily losing their senses from the ceaseless Allied shelling and air attacks that were killing more of them than their insane resistance seemed to indicate. The Wehrmacht reserved little compassion for men who lost their wits from constant combat. During World War II the Germans court-martialed and shot more than 10,000 “cowards and deserters,” inducing the soldiers manning the Hürtgen defenses to fight like the madmen they were steadily becoming. The only way for them to survive this battle was to win it. To retreat or collapse from shattered nerves were certain routes to execution, and the defense of the Hürtgen was accordingly fanatical. Masses of Allied casualties were again flooding the hospitals at Verviers, Eupen, Liege, and other Belgian cities liberated the previous summer.

From his headquarters in a nearby hunting lodge, Model carefully husbanded his formations as most remaining German reserves were channeled south to the Ardennes Forest for the approaching December counterthrust that the Allies would call the Battle of the Bulge.

The Devastated Donald Stroh

On November 17, the U.S. 16th Infantry Battalion secured pivotal Hill 232 only to come under fire from German artillery. The Americans held as the battle at last seemed to be turning in their favor.

After four days of this latest offensive, Gerow worriedly sent in the 8th Infantry Division, commanded by General Donald Stroh. Unknown to those around him, Stroh had never emotionally recovered from seeing his pilot son shot from the sky and killed during the siege of Brest the previous summer. The heartbroken general had lost the will to fight, and as his men assembled to enter the forest three hours before dawn on November 21, they had no idea their general was a man of broken spirit.

Seemingly infected by their commander’s lack of enthusiasm, the men of the 8th made little headway. Stroh did radio for support from the 5th Armored Division, but these reinforcements came to grief as they moved forward.

Advancing along the Germeter-Hürtgen road late on the night of November 24, they had to struggle through not only pitch darkness, but also a peculiar storm mingling rain, snow, and sleet. Antipersonnel mines decimated the Shermans’ accompanying infantry, and just before daylight the line of tanks encountered a huge bomb crater in the road. Engineers threw across a pontoon bridge, but the first tank to cross hit a Teller mine and blocked the road.

The Americans called down a P-47 attack as cover to try and sneak a company of riflemen through the trees to the left of the thoroughfare, but these soldiers ran into yet another minefield. As they tried to pick their way out of it they came under machine-gun fire from what they thought were U.S. positions. By dark 150 of these men were dead.

Wild Bill Weaver Takes Over the 8th Division

On the afternoon of the 26th, the undermanned 4th and 8th Infantry Divisions tried again to take the towns of Hürtgen, Kleinhau, and Grosshau. They received no artillery support so that senior American officers would have intact buildings in which to set up command posts after the villages were secured. By the 29th, the attackers were finally approaching the objectives they had sought for months. Swarms of Thunderbolts dive bombed the Nazi-occupied structures into smoldering splinters in defiance of rear echelon demands for creature comforts.

The Germans held out in cellars and wrecked houses, and that evening Grosshau was the scene of gory house-to-house fighting. Cooks, clerks, and interpreters were thrown into the melee that was bleeding both sides white. In one instance, 250 GIs died to secure a single street, but by dusk the ruins of the nondescript village were firmly in American hands. Over the past 14 days, the 4th Division had taken 4,053 killed and wounded and lost another 2,000 to trench foot, hypothermia, frostbite, respiratory illness, and combat exhaustion.

Meanwhile, the 8th Division with tank support had managed to drive the Wehrmacht from Hürtgen. Professional wrestler Lieutenant Paul Boesch described the fight for Hürtgen as “a wild, terrible, awe-inspiring thing, this sweep through Hürtgen. Never in my wildest imagination had I conceived that battle could be so incredibly impressive—awful, horrible, deadly yet somehow thrilling, exhilarating.” The adrenalin surging through the young soldiers carried them through the obscure little town whose name would haunt their troubled dreams for decades.

General “Wild Bill” Weaver had replaced the ineffective Stroh. Weaver lusted after the glory of being the man to finally clear the forest of its tenacious defenders. The struggle would sober and tame Wild Bill, shoving his ego into a small place.

General Collins was planning another corps-sized assault, this one for December 10. On the northern perimeter his 104th Division was to advance through Eschweiler to Weisweiler. In the center the freshly rebuilt 9th Division would be supported by part of the 3rd Armored Division in a drive through the woodlands to a point south of Merode. To the south the newly arrived 83rd Infantry Division was to advance on the towns of Gey and Hof Hardt bolstered by Shermans from the 5th Armored Division.

The Germans were seriously outnumbered. Their decimated 3rd Parachute and 246th Volksgrenadier Divisions were holding the line alone, but Model made sure his powerful artillery backup was ready. As the defenders noticed the U.S. troops massing in front of them, the gunners opened fire on the milling mob of green GIs.

Shortly after dawn on the 10th, the 2nd Ranger Battalion charged and quickly overcame the Germans atop Hill 400 just outside the town of Bergstein but were immediately cut to pieces by massive shelling that came from three directions. It was a horribly typical scenario.

That morning 30,000 men of the 9th and 83rd Infantry Divisions and the 3rd and 5th Armored Divisions hurled themselves against the roughly 6,000 German cadets, paratroopers, and militia still entrenched deep in the forest. These Germans had heard rumors of a great offensive in the making, and it gave them a boost of confidence as they met this latest in the wearying succession of American attacks.

A House-to-House Fight For Strass and Grey

The Hürtgen looked less like a forest every day. The huge shell craters, shattered trees, rusting tank hulks, swirls of shell-twisted barbed wire, and a carpet of mangled corpses further ripped apart by crows, vultures, and wolves created a hellish vista that inspired terror. At 7:30 am, the Americans struck unexpectedly light opposition. There was little resistance until noon, when the Nazis counterattacked straight into the U.S. spearhead. With field artillery and Sherman tanks, the 9th fended off the attack, but the battle was stalemated for the rest of the day.

The next morning, the 9th Division’s 60th Regiment hit the Germans with infantry and armor and took its objective, the town of Echtz. After securing the ruins, the Americans lost several more men who tried to remove boobytrapped German corpses.

While the soldiers of the 60th were walking around lifeless enemies in Echtz, the 39th Infantry Regiment was assaulting medieval Merode Castle. With Collins watching, the 39th, supported by tanks and Thunderbolts that helped thin out the pillboxes encircling the bastion, assailed the stronghold with artillery, bazookas, and small arms. With chunks of the walls splashing into the ice-cluttered moat, troops of the 1st Battalion charged over the drawbridge and cleared out the last of the fanatical young paratroopers inside as the castle saw its first military action since the Napoleonic Wars.

Meanwhile, elements of the 83rd Division were embroiled in grisly house-to-house combat in the towns of Strass and Gey. The division’s commander, General Robert C. Macon, was attempting to overwhelm the defenders as he assigned the entire 330th Infantry Regiment to hit Strass while the 331st Infantry Regiment went after Gey. Again, Allied numerical superiority mattered little as the Germans launched a Panzer-supported counterattack. When the 5th Division’s 744th Tank Battalion was summoned, it bogged down in a minefield and came under artillery fire. The ground was so thickly carpeted with spent shrapnel that sappers could not use their mine detectors to locate the powerful Teller mines that were disabling the Shermans.

By dusk on the 10th, Strass and Gey were captured, but the roads leading to them were still under German control. The 83rd Division’s hold on the villages was tenuous, and just before daybreak the Nazis swarmed from the woods and counterattacked into Strass, igniting a firefight that lasted all day. By nightfall, the outcome was still in question.

It was all very distracting, and while the Allied high command did consider a major enemy offensive along a lengthy stretch of the front a remote possibility, the generals assumed the ongoing violence in the Hürtgen meant that was the area through which the big push would come, if it came at all. While the latest round of frenzied fighting there continued, the Germans were quietly assembling 18 divisions and 600,000 troops behind a 60-mile-wide front just to the south.

30,000 Allied Casualties

On Saturday, December 16, the Germans launched their major offensive in the Ardennes against a thin line of inexperienced American troops. Hodges’ first thought was that the Nazi effort was a spoiling attack intended to disrupt his ongoing Hürtgen offensive. Bradley’s intelligence chief, General Edwin L. Sibert, called the mushrooming Battle of the Bulge a “diversionary attack.”

Ironically, the massive offensive gave Hodges a priceless opportunity to abort his Hürtgen fight and send units there to aid in the Ardennes, where they could have made a priceless contribution. At 1 am on December 17, Gerow asked permission to withdraw units from the Hürtgen and send them south.

Hodges replied, “No, proceed with the offensive in the north and hold where you are in the south.” It was February 23, 1945, before U.S. forces finally cleared the Hürtgen Forest and forded the bordering Roer River.

Model was out of time. The ardent Nazi wandered into a wooded area outside the industrial town of Duisberg and blew his brains out with his service pistol.

Predictably, those Allied commanders responsible for the Hürtgen bloodbath were not anxious to speak of the operation with its heavy casualties. In his thick postwar memoir Crusade in Europe, Eisenhower allotted exactly 52 words to the campaign. More than 30,000 Allied soldiers died or were maimed.

Constantly pelted by rain, sleet, and snow the Hürtgen Forest had been unable to burn despite months of blistering combat. Yet, the unmistakable signs of the battle remain. The ground is hillocked and lumpy from shellfire, the trees are scarred, and the soil, enriched by rusting iron and blood, is among the most fertile in the world. Few survivors from either side have ever returned to visit.

My Uncle Sgt Mitchell L. Chapman was a gunner on a 1917 .30 cal machine gun in this battle.

My Dad, T/SRG Arlie Kisner (from WV)630th TD BN. Company C attached to 112th of 28 Division was there.

I found this article to be descriptive, informative and comprehensive – until the end when it devolves into what I consider to be lazy writing and bad editing. It goes from the battle of the bulge in December to the end of the battle by 2/23/45, with no information as to how such a deadly battle got there. And then it goes on to say, “Model was out of time”, and blew his brains out. A reader who knew little of Model and the events occurring in that area of Germany would infer that all of that happened at the same time. They did not. Model was far from out of time, as the planners of and the combatants in Operation Varsity and Plunder, begun 3/24/45, well knew. Model was in command of 300,000 men in 2 armies and a number of divisions in the Ruhr. Armies that still fought and killed the invaders. It wasn’t until 4/2/45 that those men were trapped by the 9th and 1st American armies. Trapped because Hitler refused to allow Model to breakout of the unfolding trap. Model refused to surrender to the American armies; instead, he dissolved his armies, leaving it up to individual commanders the decision to surrender or fight. (Most decided to surrender.) He committed suicide on 4/21/45, two months after this article implies that he did.