By John Walker

With just an hour of daylight remaining on the smoke-shrouded battlefield near Gaines’ Mill six miles northeast of Richmond, Virginia, Confederate General Robert E. Lee sought out one of his most promising officers, Brig. Gen. John Bell Hood. The commander of the Army of Northern Virginia’s troops had been launching uncoordinated attacks throughout June 27, 1862, against Union works on the slopes east of Boatswain’s Creek without making a dent in the enemy’s line. There was only time for one more attack.

As the sun dipped low in the sky, Lee had finally managed to gather all his forces for a general attack along a 21/2-mile front. He remained confident that he could turn the potential defeat into victory, and he wanted Hood’s Texas brigade to spearhead the assault. Lee told Hood what he needed, omitting none of the difficulties the previous attackers had encountered.

“This must be done,” Lee told Hood. “Can you break his line?” When the young brigadier replied that he would try, Lee turned to ride away and said, “May God be with you.” Hood’s five regiments were about to charge across the swamp and into history.

Robert E. Lee’s Plan to Break the Siege of Richmond

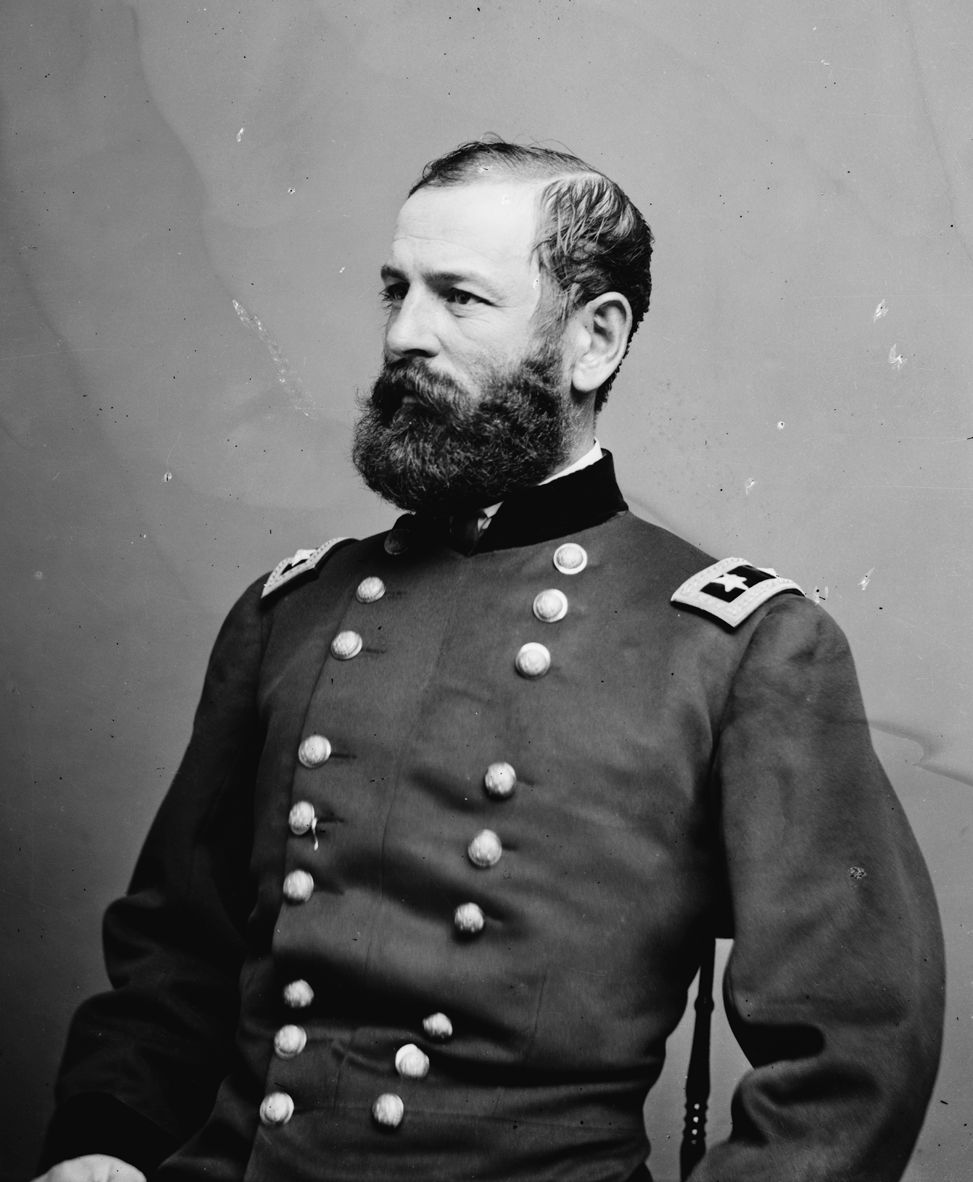

After an almost uninterrupted four-month string of Union successes in early 1862 put the very survival of the Southern Confederacy in jeopardy, Maj. Gen. George McClellan, the commander of the Army of the Potomac, advanced up the Virginia Peninsula and by mid-June had five Union infantry corps deployed on the eastern outskirts of Richmond, one on the north side of the rain-swollen Chickahominy River and four on the south side. “Little Mac’s” intention was to advance just a bit farther westward and capture Old Tavern on the Nine Mile Road, entrench, and deploy his siege guns to pound the city into rubble. His siege train included enormous 13-inch sea mortars. The rebellion would be brought to an early end with minimal Union casualties.

Lee, who had assumed command after Maj. Gen. Joseph Johnston was wounded on May 31 at the Battle of Seven Pines, had managed in a matter of weeks to concentrate his forces and improve Richmond’s defenses somewhat, but knew he could not defeat McClellan’s 94,000 entrenched troops.

Lee devised an elaborate strategy to drive the enemy host from the outskirts of the capital, destroy it, and revive his country’s sagging fortunes. He would shatter the isolated Federal right flank north of the Chickahominy held by the 27,000-man V Corps, commanded by Maj. Gen. Fitz-John Porter, and threaten the Army of the Potomac’s line of supply which ran to White House Landing on the Pamunkey River. When McClellan evacuated his works east of Richmond to protect his vital supply base, the Confederates would catch his huge main force in the open and destroy it as well.

After Maj. Gen. Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson returned to the Richmond area from the Shenandoah Valley with his reinforced corps, Lee planned to concentrate the bulk of his army, six divisions totaling approximately 60,000 men, on the Chickahominy’s north bank early on June 26. “Old Jack” already sent Brig. Gen. James Ewell Brown Stuart on a cavalry reconnaissance to locate McClellan’s right flank. “Jeb” reported that it did not extend beyond the headwaters of Beaver Dam Creek and was unanchored. Sending the majority of the Confederate troops into battle north of the Chickahominy River would leave fewer than 25,000 Confederates, many of whom were green recruits, south of the river under Maj. Gen. John Magruder and Maj. Gen. Benjamin Huger where they would be holding a position opposite McClellan’s main body of 67,000 men. If McClellan figured out Lee’s intention, and showed some initiative, he could try to fight his way through Magruder and Huger into Richmond. But Lee had a good measure of his opponent, and he doubted McClellan would seize such an opportunity.

The key to Lee’s plan was maneuver. When Jackson arrived in the area on the morning of June 26, he would link up with one of Maj. Gen. Ambrose Powell (A.P.) Hill’s advance brigades, after which their two columns would march southeasterly onto and around the reported enemy flank near the northern end of Beaver Dam Creek. While this was underway, Stuart’s 2,000 troopers would cover Jackson’s left. Meanwhile, A.P. Hill would lead his other five brigades across the Chickahominy at Meadow Bridge, drive eastward, and clear Mechanicsville of enemy forces, allowing the divisions of Maj. Gen. James Longstreet and Maj. Gen. Daniel Harvey (D.H.) Hill to cross the river and fall in behind the surging Confederate tide. With vast gray columns advancing on his front, flank, and rear in echelon, Lee believed, the outnumbered Porter would have to abandon his position to avoid encirclement and annihilation. It was a classic Napoleonic tactic.

The Seven Days Battle Begins

With the success of Lee’s strategy depending entirely upon Jackson’s timely arrival, the June 26 attack immediately went awry. Jackson, feverishly ill and exhausted from his spring 1862 Valley Campaign, did not get his column onto the road until 8 am, six hours behind schedule. Destroyed bridges, muddy roads, and enemy skirmishers impeded his column’s march, and when supply wagons failed to keep up hundreds of stragglers left the column in search of food and fresh water. When the Confederate vanguard reached Pole Green Church near Hundley’s Corner at 5 pm, Jackson could clearly hear the sounds of pitched battle three miles to the south. With his force strung out behind him along two roads and believing he had obeyed Lee’s orders to the letter, Jackson put his men into bivouac without notifying Lee or anyone else of his arrival, a confounding lapse by one of the South’s most aggressive commanders. As it turned out, Lee had based Jackson’s arrival on a faulty map that placed Hundley’s Corner near the headwaters of Beaver Dam Creek when it was actually three miles farther north.

In the meantime, A.P. Hill had crossed the Chickahominy that afternoon and initiated Lee’s attack on his own. He cleared Mechanicsville and pursued the retreating Federals toward Beaver Dam Creek. When he learned A.P. Hill had advanced without Jackson, Lee saw no option but to continue the assault. Neglecting to concentrate his division’s nine artillery batteries to contest the enemy’s guns, “Little Powell” led half his division eastward into battle. The result was a bloody, costly repulse. With three brigades stalled in the Union front, Lee unwisely sent two more to test the enemy’s left near Ellerson’s Mill. This attack also was repulsed with devastating losses. In the first clash of the Seven Days Battle, which was Lee’s offensive to drive McClellan from Richmond, the Army of Northern Virginia had suffered a major defeat.

McClellan’s “Change of Base”

Despite numerous deficiencies exhibited by the Confederate army, Lee’s offensive strategy was working. Jackson’s arrival northeast of Richmond had rendered the Federal position north of the river untenable. Unknown to Lee, McClellan had already decided to abandon his vulnerable base at White House Landing in favor of one located south of the Chickahominy. As reports of Jackson’s arrival came in on the night of June 26, McClellan knew he had to act or Porter’s corps would be swallowed whole. Ruling out offensive action on either side of the river, much to the chagrin of subordinates who urged him to exploit Porter’s victory, and imagining overwhelming force wherever he looked, McClellan opted to abandon his offensive and retreat, not back down the Virginia Peninsula the way he had come, but due south to the nearest haven, the James River. McClellan termed his retreat a “change of base” that would save his army. Porter was told to fall back to a new defensive position near Gaines’ Mill that would cover the river crossings and hold the Confederates at bay. Although McClellan was already defeated, his army still had plenty of fight left in it.

At 3 am on June 27, Brig. Gen. George McCall, whose three infantry brigades had fought and won the Battle of Mechanicsville, got the order to withdraw from the Beaver Dam Creek line. Rear guards supported by artillery screened the movement, holding the creek crossings until after sunrise, when Rebel skirmishers advanced as soon as it was light enough to see. Except for two companies of the 13th Pennsylvania, who did not get the order and were captured, all the Union men and guns made good the three-mile withdrawal to a new position beyond Boatswain’s Creek, which also was referred to as a swamp. After shifting brigades so fresh troops could attack at dawn, Lee arrived in Mechanicsville determined to achieve everything on June 27 that was not accomplished on June 26. When it became obvious that the enemy was falling back, Lee had A.P. Hill push across Beaver Dam Creek. The Confederate commander ordered Magruder and Huger to hold the Richmond works “at the point of the bayonet if necessary.”

One of Lee’s first moves that morning was to send an aide to guide Jackson south from Hundley’s Corner to join the main Confederate body. Lee met Jackson and A.P. Hill at 10 am and explained his plan to envelop the enemy. Jackson would march northeastward on Cold Harbor Road across the headwaters of Powhite Creek to Old Cold Harbor, where he would be joined by D.H. Hill. Hill was already in motion, conducting his own wider turning movement on the Old Church Road farther north. When joined, D.H. Hill and Jackson would command 14 of the army’s 26 infantry brigades. On the Confederate right, Longstreet would move his division down the River Road along the bluffs overlooking the Chickahominy River in support of A.P. Hill’s advance in the center toward Powhite Creek and Gaines’ Mill. Unlike the previous day, Hill had orders to attack the Federals wherever he found them. He put Brig. Gen. Maxcy Gregg’s brigade of well-rested South Carolinians, which had been held in reserve the previous day, at the front of his division.

Nearly Impregnable

By mid-morning Porter had his reinforced corps on the plateau behind Boatswain’s Creek, which enclosed a horseshoe-shaped position of great natural strength. The oval-shaped plateau was about two miles wide and a mile deep with its long outer side facing north. The Watt, McGehee, and Adams families each had homes on the plateau, and the cleared land around these structures furnished superb fields of fire for defenders. The highest elevation was known locally as Turkey Hill, though the day’s battle would take its name from a site a mile away, the home and grist mill of Dr. William Gaines. The doctor was the area’s largest landowner and was renowned for his support of the rebellion. Union troops had been camped on his land for several months and had, over his protests, buried a number of their fever-stricken dead on the property. Gaines had defiantly announced he would dig up the bodies and feed them to his hogs after the Yankees were driven away.

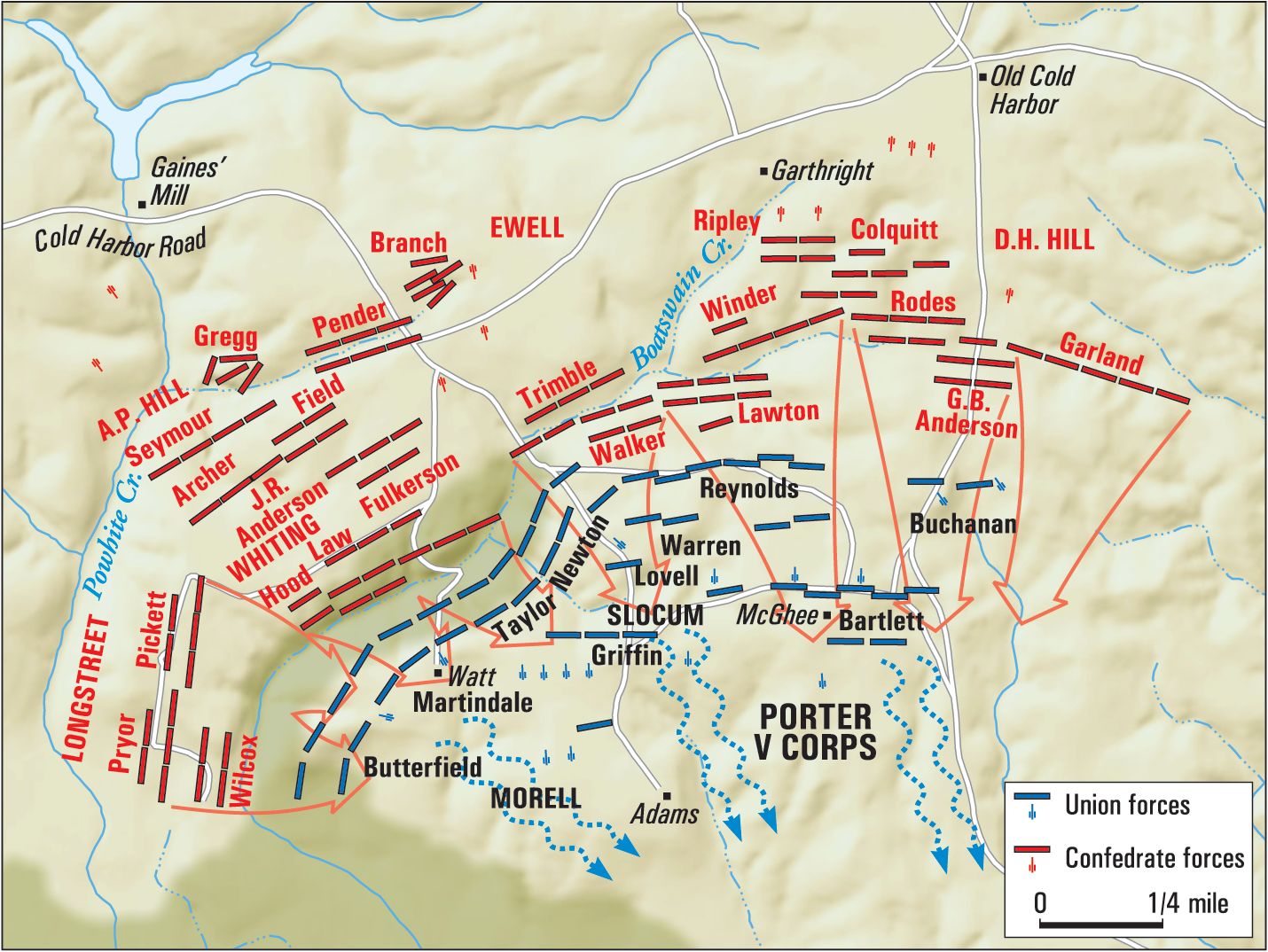

Rising at the northeast corner of the plateau and curving around its northern and western sides before emptying into the Chickahominy River, Boatswain’s Creek was a sluggish little stream, its banks and bottomlands heavily overgrown with trees and underbrush. The ground to the north and west was largely open and under cultivation and sloped down to the swampy bottomland. Porter arranged his corps in a crescent-shaped line almost two miles long facing north and west. Brig. Gen. George Morell’s division covered the left flank on Turkey Hill, and Brig. Gen. George Sykes’ division held the right flank. Morell’s position was nearly impregnable. The Yankees were posted in a first line on the eastern edge of the bottomland and in a second line halfway up the hillside. McCall’s division was deployed in a third line along the crest of the plateau as the reserve. Two companies of Colonel Hiram Berdan’s U.S. Sharpshooters were deployed in the first line.

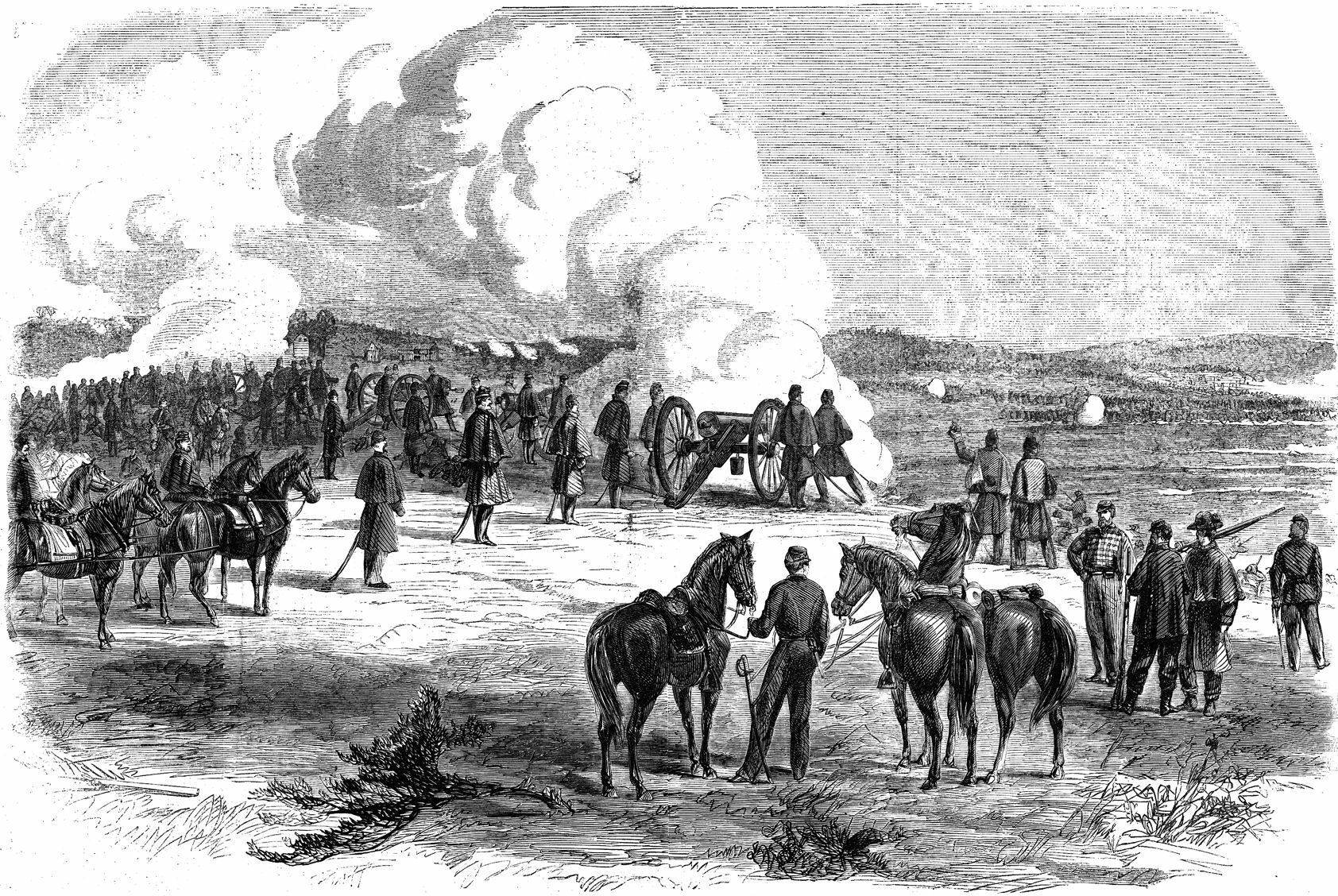

The infantrymen in all three lines sheltered behind hurriedly fashioned earthworks of logs, fence rails, and dirt. Believing he was not strong enough to extend his line back to the Chickahominy River on his right, Porter relied on the boggy, broken ground there to discourage a turning movement. Porter had 96 guns with which to support his infantry. The guns were positioned along the third line of works or in reserve on the plateau. Adding additional firepower were three batteries of long-range guns on the south bank of the Chickahominy where they could assist Morell’s division. Brig. Gen. Philip St. George Cooke’s five cavalry companies were posted on the far left, covering the ground between Morell’s division and the river.

Fighting in the Swamp

As A.P. Hill’s troops advanced toward the enemy’s picket line beyond Powhite Creek, the day’s first contact took place three miles away, entirely unknown to Lee, after D.H. Hill’s troops arrived at Old Cold Harbor well ahead of Jackson. Old Cold Harbor was a nondescript crossroads hamlet. Another small village, New Cold Harbor, was situated a mile and a half to the west.

When D.H. Hill pushed two brigades down the road toward the Chickahominy River from Old Cold Harbor, his skirmishers were hit by sharp musket fire from behind a stream to their front and artillery fire from the slope beyond. An Alabama battery, hurried forward to suppress this fire, was bombarded so severely by rifled guns from the high ground to the east, which were manned by U.S. Regulars from Sykes’ division, that it was quickly withdrawn.

Hill realized he had met far heavier resistance than was expected and also seemed to be facing the enemy’s front rather than his flank. The stream behind which the Union infantry sheltered was not shown on Hill’s map, and therefore he wisely decided to await Jackson’s arrival. This action took place a little after noon, but Lee learned nothing of it or the enemy’s position. Normally the sound of artillery at that distance would be heard, but on that hot and sultry day there were so-called acoustic shadows. These heavy pockets of dense, moist air scattered across the field frequently muffled the sounds of battle.

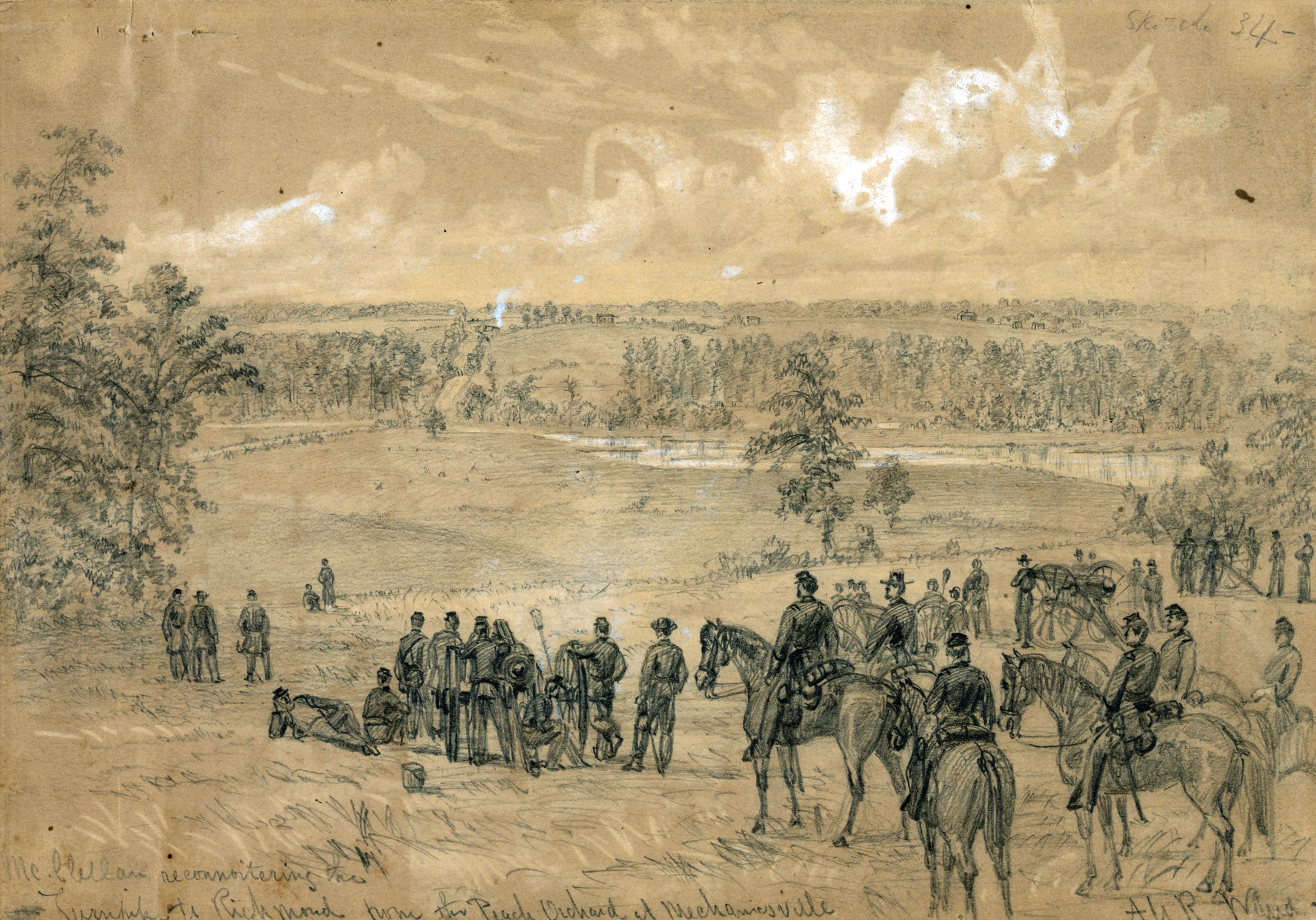

In their first action of the war, Gregg and his men pushed down Telegraph Road and reached Powhite Creek at Gaines’ Mill around noon. Told to expect a fight there, Gregg’s troops met only desultory fire and continued on across the creek to New Cold Harbor, moving on the run down a slope toward a wooded area that bordered yet another swampy body of water. The Battle of Gaines’ Mill erupted in earnest at about 2:30 pm. From across the swamp came withering musket fire, joined by shell and solid shot from Union guns on the high ground, that halted Gregg’s men and drove them back in confusion. After Gregg rallied his shaken regiments and reported back to A.P. Hill that he had made contact with the enemy, Hill and Lee rode up for a look. Lee quickly realized the Federals had taken their stand not behind Powhite Creek as he expected, but in a far more imposing position behind a creek that did not appear on his maps. Furthermore, the enemy was facing north as well as west and appeared to be in great force.

More than 2,000 Casualties in Two Hours

Believing Jackson and D.H. Hill would soon be adding their weight to the contest, Lee told Gregg to hold his position until the rest of the division came up to renew the assault. After the brigades of Brig. Gens. Lawrence Branch, Dorsey Pender, Joseph Anderson, Charles Field, and James Archer formed up on Gregg’s right, the Confederate battle line stretched for almost a mile. Once again the attackers failed to mass their guns for concentrated fire, and both the gunners and infantrymen would suffer as a result. Most of A.P. Hill’s men would have at least a quarter of a mile of open ground to cross before they reached Boatswain’s Creek. From his command post at the Watt home on Turkey Hill, Porter observed Hill’s brigades deploying for battle and rising dust clouds off to his left along the River Road and signaled a request for reinforcements to army headquarters. Brig. Gen. Henry Slocum’s division had been designated to serve as reinforcements if necessary. McClellan, coordinating his army’s efforts by telegraph from his headquarters south of the river, and thus not personally directing any of the actual fighting, relayed the request to VI Corps, and Slocum’s division tramped across the river at Alexander’s Bridge.

A.P. Hill ordered his 12,000-man division to advance at 2:30 pm. Brig. Gen. George Morell’s division numbered a thousand fewer men than A.P. Hill’s, but with a part of Sykes’ division also engaged the defenders there had a small advantage in numbers. They also held a considerable advantage in artillery. They had three batteries posted on the plateau’s lower slopes to thwart Hill’s attack in addition to those packed tightly on the crest. The Confederate gunners made little impression on this formidable array. When Captain D.G. McIntosh’s Pee Dee Artillery came onto the field, dust and smoke so obscured the swamp and surrounding hills that McIntosh could not tell friend from foe and ceased firing after three rounds.

Gregg’s attackers, after forcing a lodgment in the center of the Union line where the divisions of Morell and Sykes met, were soon engaged in fierce fighting. The 1st South Carolina Rifles charged with fixed bayonets against a Union battery and clashed with its supporting infantry, the 5th New York Zouaves, and after hand-to-hand fighting were forced back with the loss of 309 men killed or wounded. The rest of Gregg’s brigade fared little better. Branch’s brigade, which like Gregg’s had not seen action the previous day, was badly battered during the two-hour assault and lost 401 men.

Berdan’s Sharpshooters, in particular, contributed to the heavy toll. Posted as skirmishers, they moved from tree to tree along the swamp’s eastern edge, feeding cartridges into their Sharps breech-loading rifles and firing from ranges as short as 40 yards. None of Hill’s brigades except Gregg’s gained even a toehold beyond Boatswain’s Creek. Anderson’s brigade launched three spirited but unsuccessful charges, while Field’s became so entangled in the swampy undergrowth that his second line poured volleys of friendly fire into the men in the first rank, forcing the colonel of the 47th Virginia to order his men to fall flat to avoid fire coming from both front and back. In two hours, A.P. Hill’s division suffered more than 2,000 casualties while fighting unsupported.

“That’s Hell in There”

Captain William Biddle of McClellan’s staff arrived at Turkey Hill about this time and found Porter calmly sitting atop his horse behind a strip of woods overlooking the Union left, while a tide of wounded men streamed past and shells exploded all around. A staff officer asked him if he had a message for headquarters. “You can see for yourself, Captain,” said Porter. “We’re holding them, but it’s getting hotter and hotter.” At that moment, the vanguard of Slocum’s division arrived from the river crossing, raising Porter’s numbers to 36,400, and he rode off to plug reinforcements into the line.

In the meantime, Jackson was struggling to bring his forces to bear where Lee wanted them. He had obtained a guide that morning after meeting with Lee but neglected to offer precise directions as to how he wanted to reach Old Cold Harbor. The guide took the shortest and most direct route, one that led past Gaines’ Mill. When Jackson realized he was not arriving on the enemy’s right flank as Lee wanted, he ordered the column to turn around and countermarch to Cold Harbor Road, delaying the Valley forces’ arrival on the field for almost two hours. Maj. Gen. Richard Ewell, in Jackson’s van, was the first to reach Old Cold Harbor, where he found Lee’s aide, Lt. Col. Walter Taylor, anxiously awaiting him. Worried Porter would mount a counterattack against A.P. Hill’s battered division, Lee had dispatched Taylor to find any of Jackson’s units and get them into battle as soon as possible. At the same time, Lee told Longstreet on the right to make at least a diversion in support of A.P. Hill. It was almost 4 pm when Lee met Ewell on Telegraph Road and told him to attack with his three brigades against the Union center where Gregg and Branch had been beaten back. Lee also sent one of Ewell’s aides to locate the rest of Jackson’s corps and get them to the field as well.

Ewell sent in his lead brigade, the Louisiana Tigers under Colonel Isaac Seymour, without waiting for the rest of his division. After Seymour was killed, his troops became confused in the boggy thickets of the creek. Command devolved to Major Roberdeau Wheat, the commander of the 1st Louisiana Special Battalion, who was mortally wounded. The Tigers wavered and then fled to the rear.

Ewell’s next brigade under Brig. Gen. Isaac Trimble attacked in piecemeal fashion with just two of its regiments, the 15th Alabama and 21st Georgia. “Boys, you are mighty good but that’s hell in there,” a retreating Louisianan warned them as both regiments charged into murderous rifle and cannon fire without hesitation. Neither was able to advance beyond the western edge of the bottomland.

Attrition on the Union Lines

The Union lines held against these repeated attacks, but each took a toll. Since their midday skirmish near Gaines’ Mill, the Irishmen of the 9th Massachusetts had repulsed consecutive attacks by Branch, Pender, and Trimble and were out of ammunition. The nearby 5th New York Zouaves, after losing a third of their number in a succession of charges and countercharges, was sent to the rear for rest and resupply. As Porter moved units from McCall’s reserve into the hardest hit parts of his line, the 9th Pennsylvania advanced with fixed bayonets to relieve the 9th Massachusetts. “We chased them across a field into some woods, but then they got reinforcements and we had to fall back,” wrote Corporal Adam Bright. “Three times we reformed our lines and charged them but could not get them out of the woods.” More of Slocum’s troops were arriving at this point, inserted like McCall’s into the lines where they were most needed.

Confederate President Jefferson Davis and his entourage were observing the fighting from high ground one mile behind the front but could see little of the fighting in the tangled bottomland. On the extreme Confederate right, Longstreet ordered Brig. Gen. George Pickett’s 2,000-man brigade to attack the Union position behind Boatswain’s Creek to assist A.P. Hill’s hard-pressed division. The Virginians marched downhill and disappeared into the thickets near the water’s edge. Concentrated artillery fire from the crest of Turkey Hill and the south bank of the Chickahominy, pummeled the Virginians. Longstreet learned from walking wounded of the attack’s failure. “Old Pete” realized that it would take the entire army attacking in concert to dislodge the enemy from the hill.

Though the attacks of A.P. Hill, Ewell, and Longstreet had been repulsed, Porter was growing more anxious by the minute. By 5 pm his men were exhausted, dehydrated, low on ammunition, and their weapons fouled. “I am pressed hard, very hard,” he informed headquarters. “About every Regiment I have has been in action, and unless reinforced I am afraid I shall be driven from my position.” Having made no contingency plans for such a situation, McClellan sent no immediate reinforcements, but instead merely asked his subordinates if they had any troops to spare. McClellan finally dispatched two of Maj. Gen. Edwin Sumner’s brigades, but due to their location it would be almost three hours before they arrived.

“Sweep the Field With the Bayonet!”

Jackson had finally arrived at Old Cold Harbor and, at last cognizant of the situation and the enemy’s dispositions, was trying to get his remaining forces into the fray. These were the divisions of Brig. Gen. William H.C. Whiting and Brig. Gen. Charles Winder, at that point stretched out for several miles along Cold Harbor Road. Rather than sending his ailing chief-of-staff, Major Robert Dabney, to guide these units into position, Jackson gave hurried, complicated verbal orders to another aide, his quartermaster Major John Harmon.

The two fresh divisions were to move into line in echelon between D.H. Hill and Ewell. If that failed, they were to move toward the sound of heaviest firing. Knowing little of tactics, Harmon became hopelessly confused when he attempted to relay Jackson’s instructions to Whiting and Winder, after which the puzzled generals remained stationary for another precious hour. As the roar of gunfire intensified all along the front, Dabney realized what had taken place and rode over and conveyed the correct orders. One after another, six more Confederate brigades finally began moving into line.

Some of the brigades had two miles to march and others encountered further confusion when they neared the front but, with the daylight beginning to fade, overriding everything else was a sense of urgency. After Jackson met briefly with Lee on Telegraph Road, he rode back to his units and dispatched couriers to his two brigadiers. “Tell them this affair must hang in suspense no longer,” said Jackson. “Sweep the field with the bayonet!”

But getting these scattered units into position in the woods and marshes was a painfully slow and difficult process. As a result, two of Winder’s brigades ended up in the reserve behind Longstreet’s division on the far right a mile from the rest of Winder’s men. Whiting commanded the brigades of Hood and Colonel Evander Law. As he marched the two brigades toward the sound of the heaviest firing, Whiting had allowed them to drift to the right. They went into action on Longstreet’s left, under that officer’s direction.

“A Perfect Storm of Lead”

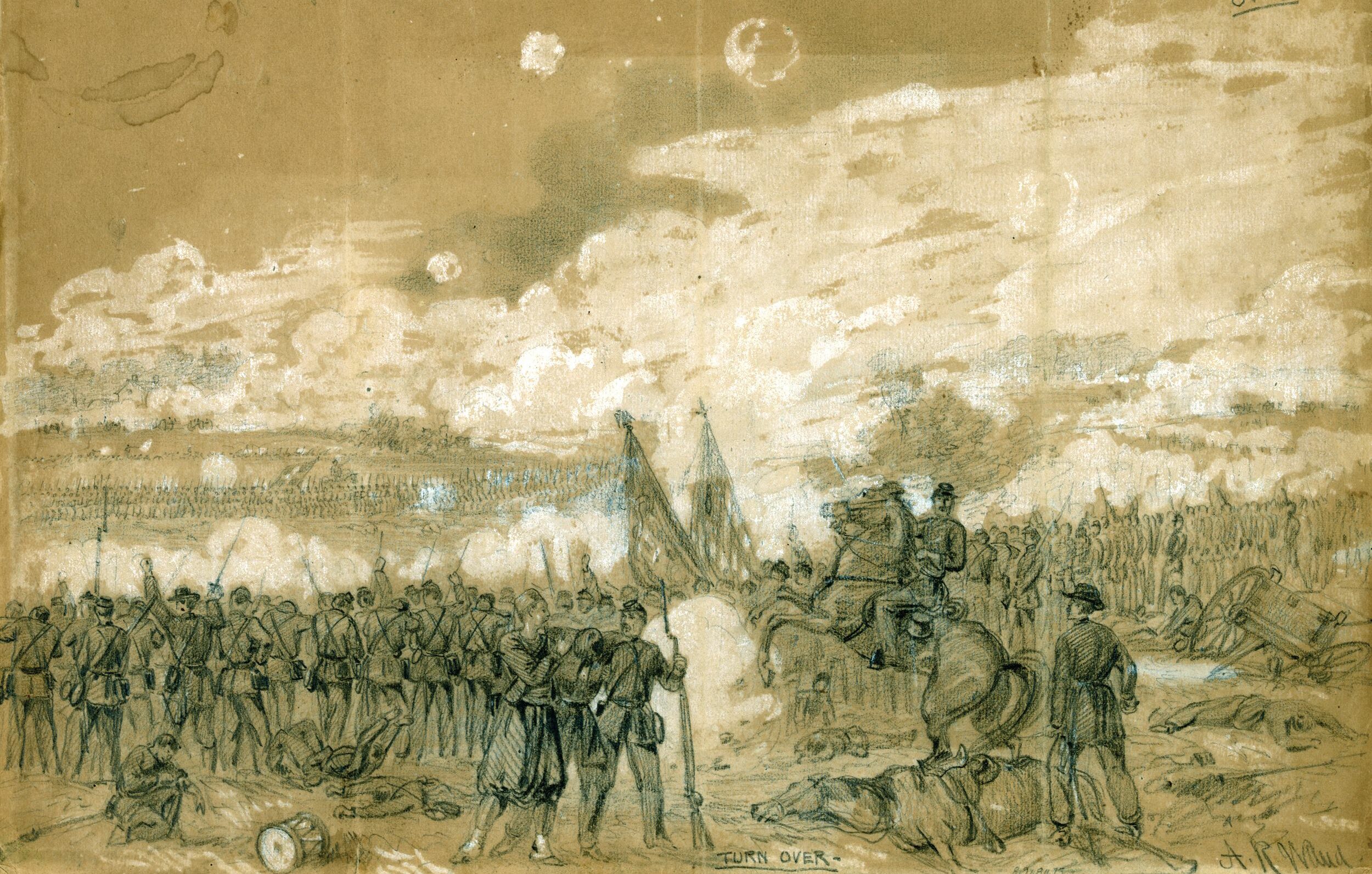

It was almost 7 pm and the setting sun appeared a dull red to the soldiers through the haze of smoke and dust. With A.P. Hill’s division and part of Ewell’s too exhausted for further fighting, and one of Longstreet’s brigades allocated to the reserve, Lee deployed 16 brigades totaling 32,100 into line for the final attack. The battle line stretched in a great arc for two miles. On the right the soldiers faced east and on the left they faced south. With McCall’s and Slocum’s divisions fully engaged, Porter’s strength was approximately 34,000 men, even though many of the men in the front-line divisions of Morell and Sykes were worn out after hours of heavy fighting. Moreover, a number of McCall’s and Slocum’s regiments had been put into line haphazardly, which was apt to lead to significant confusion as the attack went forward.

After Lee ordered his entire line forward, the climax of the Battle of Gaines’ Mill turned into a confused melee. D.H. Hill faced a daunting task on the Confederate left. The slope to the crest of the hill was 400 yards long. The stretch of hillside was entirely open, and the Federals had placed a battery near the McGehee home to contest any advance with enfilading fire.

D.H. Hill’s five brigades went in and quickly became entangled in the swamp, emerging from the woods and marshes piled one behind the other. One regiment, the 27th North Carolina, suffered heavy casualties in a vain effort to seize the battery’s guns. Struggling mightily toward the crest of the hill, the bulk of Hill’s division engaged in savage fighting with Sykes’ Regulars in an orchard near the McGehee home that became a bloody battlefield. “Every post, bush, and tree now covers a man who is blazing away as fast as he can,” wrote Sergeant Thomas Evans of the 12th U.S. Infantry. “Column after column of the enemy melts away like smoke but is quickly re-formed and again rushes on.”

Successive waves of Confederates rushed the Yankee line. Brig. Gen. Alexander Lawton’s 3,600-man brigade eagerly advanced into their first fight of the war against the Union center. The Stonewall Brigade of Winder’s division pushed into line on Lawton’s left next to D.H. Hill, joined by a fresh brigade from Ewell’s division and Trimble’s reformed brigade. On the Confederate right, Longstreet’s division faced the most difficult terrain and heaviest cannon fire of any attacking unit. His men also had to cross almost a quarter mile of open ground to reach the swamp and the first line of enemy works. “Up to the crest of the hill we went at a double quick, but when we came into view on the top of the ridge we met such a perfect storm of lead right in our faces that the whole brigade literally staggered backward several paces as though pushed by a tornado,” wrote Corporal Edmund Patterson of the 9th Alabama.

The Final Confederate Assault

Whiting’s two-brigade division, which numbered fewer than 8,000 men, moved into position and constituted what amounted to the left wing of Longstreet’s assault. Hood’s Texas Brigade comprised the 1st Texas, 4th Texas, 5th Texas, 18th Georgia, and the South Carolina Legion. After observing the fierce resistance offered by the well-posted Union defenders, Whiting realized that if the attack was to succeed then Law’s and Hood’s brigades would have to advance without pausing to fire, cover the open ground down to the swamp as swiftly as possible without losing order, and punch through the Yankee line.

As he moved his five regiments into line on Law’s left, Hood noticed a gap between Law and Longstreet and therefore split his command, marching the 4th Texas into the gap. For some unknown reason, several companies of the 18th Georgia attached themselves to the 4th Texas as well. Because of these circumstances, Hood would send his brigade forward on both flanks of Law’s brigade. Ignoring the jurisdiction of the 4th Texas’ colonel, John Marshall, Hood assumed personal command of his old regiment. Marshall was killed just minutes into the advance.

With Hood leading the advance on foot, more than 500 men of the 4th Texas and 18th Georgia stepped off. The field to their front was littered with dead and wounded comrades, smashed artillery caissons and carriages, stricken horses, and broken ammunition wagons. Law’s and Longstreet’s men kept pace alongside. They held their fire and tried to make as little noise as possible. As fire from the massed batteries on Turkey Hill tore holes in the gray line, the number of dead and wounded mounted rapidly.

Hood seemed to be everywhere at once. He urged men forward, shouted for them to close on the colors, and ordered them to continue to hold their fire. As the range closed to 300 yards, fire from Berdan’s Sharpshooters and Brig. Gen. John Martindale’s and Brig. Gen. Charles Griffin’s front-line troops exacted a horrendous toll. Hood’s men fell by the score, but the survivors closed ranks and pushed on.

About 150 yards from the swamp Hood’s companies passed through a line of Confederates who were hugging the ground and ignoring the entreaties of their young lieutenants to advance. Disregarding the pleas of these demoralized men to turn back, Hood’s troops reached the top of a ridge that led down to the swamp, the ridge marking the farthest advance of A.P. Hill’s men. As Hood’s soldiers pushed over the rise and started down the slope toward the swamp, sheets of flame erupted from the Union works to their front.

“The fire of the enemy was poured into us with increasing fury, cutting down our ranks like wheat in a harvest,” wrote Private William R. Hamby of the 4th Texas. Law and Hood would lose a total of 1,018 men this day, most of them during this sprint to the water’s edge. When they were within 100 yards of the swamp, the order went out to fix bayonets while on the move and advance at the double quick. They finally hit the swamp and at point-blank range from the first line of Federals raised the Rebel yell. Concurrently, off to the right, a half-mile-long line of Longstreet’s troops were crashing into the swamp, traversing the water, and scrambling up the slope.

The Union Rout

Porter’s numbers there were at least equal to those of the attackers. With even the best infantryman able to get off no more than three rounds a minute, the exhausted defenders could not fire fast enough to halt the swift advance. The Federals in the first line panicked, turned, and fled, and in their rush to the rear blocked the fire of the troops in the second line, carrying those defenders along with them. As the blue tide surged toward the crest of Turkey Hill, Confederate infantrymen stopped to fire at last.

“One volley was poured into their backs, and it seemed as if every ball found a victim, so great was the slaughter,” wrote a Texan. With a breach finally accomplished in the Federal center, Porter’s left and right flanks crumbled as Longstreet and Jackson widened the rupture in both directions. On Jackson’s left, Ewell and D.H. Hill outflanked Sykes’ Regulars, forcing them to fall back.

At that point, the battlefield contracted rapidly toward the river crossings. Those Union regiments still under firm control, mostly the Regulars, withdrew without panicking, halting to fire occasionally before continuing on. Others fell back in disorder. The Rebel objective at that point became the enemy’s artillery on the plateau. As the range closed, Yankee gunners switched to canister rounds, but as their infantry supports began leaving the field the gunners came under merciless fire as well. After capturing 10 guns from the batteries along the crest, the attackers turned their attention to a second line of guns in reserve on the plateau and encountered, to their surprise, a Napoleonic-style cavalry charge. St. Cooke had, without orders, led his command up the hill to support the threatened batteries and, with sabers drawn, 250 men of the 5th Cavalry charged the advancing Confederates. The attack accomplished nothing but the death of 55 troopers.

McClellan Abandons the Peninsula Campaign

The victorious Confederates captured nine more guns and two entire Federal regiments, which became lost in the hasty retreat that followed the Union collapse. Unfortunately for Lee and his generals, there was too little daylight remaining for another concerted Confederate push. Sykes’ troops, maintaining their reputation by retiring in good order, joined with Sumner’s two brigades, which had just arrived, to cover the retreat while Porter got the rest of his army and his reserve artillery across the river in the darkness. Gradually the fire slackened and then died away.

Lee sent a message to Jefferson Davis that the Army of Northern Virginia had gained its first victory. But the victory had come at a dreadful cost. The Army of Northern Virginia suffered 1,483 men killed, 6,402 wounded, and 108 missing. As for the Army of the Potomac, it suffered 894 killed, 3,114 wounded, and 2,829 captured.

The two armies had together put a staggering number of men onto the field, 96,000 including reinforcements, making Gaines’ Mill the costliest and largest battle of the Peninsula Campaign. McClellan was fortunate that it was not a great deal worse. Only poor Confederate communications, the stoutness of Sykes’ Regulars in retreat, the last-minute arrival of two of Sumner’s brigades, and darkness saved his command from being driven against the Chickahominy and wiped out before it could cross four narrow bridges to safety.

“Had Jackson attacked when he first arrived, or during A.P. Hill’s attack, we would have had an easy victory, comparatively, and would have captured most of Porter’s command,” wrote Colonel Porter Alexander, the Army of Northern Virginia’s chief of ordnance.

That night, after a day during which he had allowed more than 60,000 Union soldiers to sit idly by south of the river while Porter’s lines were being driven in in savage fighting, McClellan announced he would do what he had privately already decided to do: abandon the campaign and seek a new base on the James River. Lee closed his message to Davis, “We sleep on the field, and shall renew the contest in the morning.”

Thank You for your fine magazine