By David H. Lippman

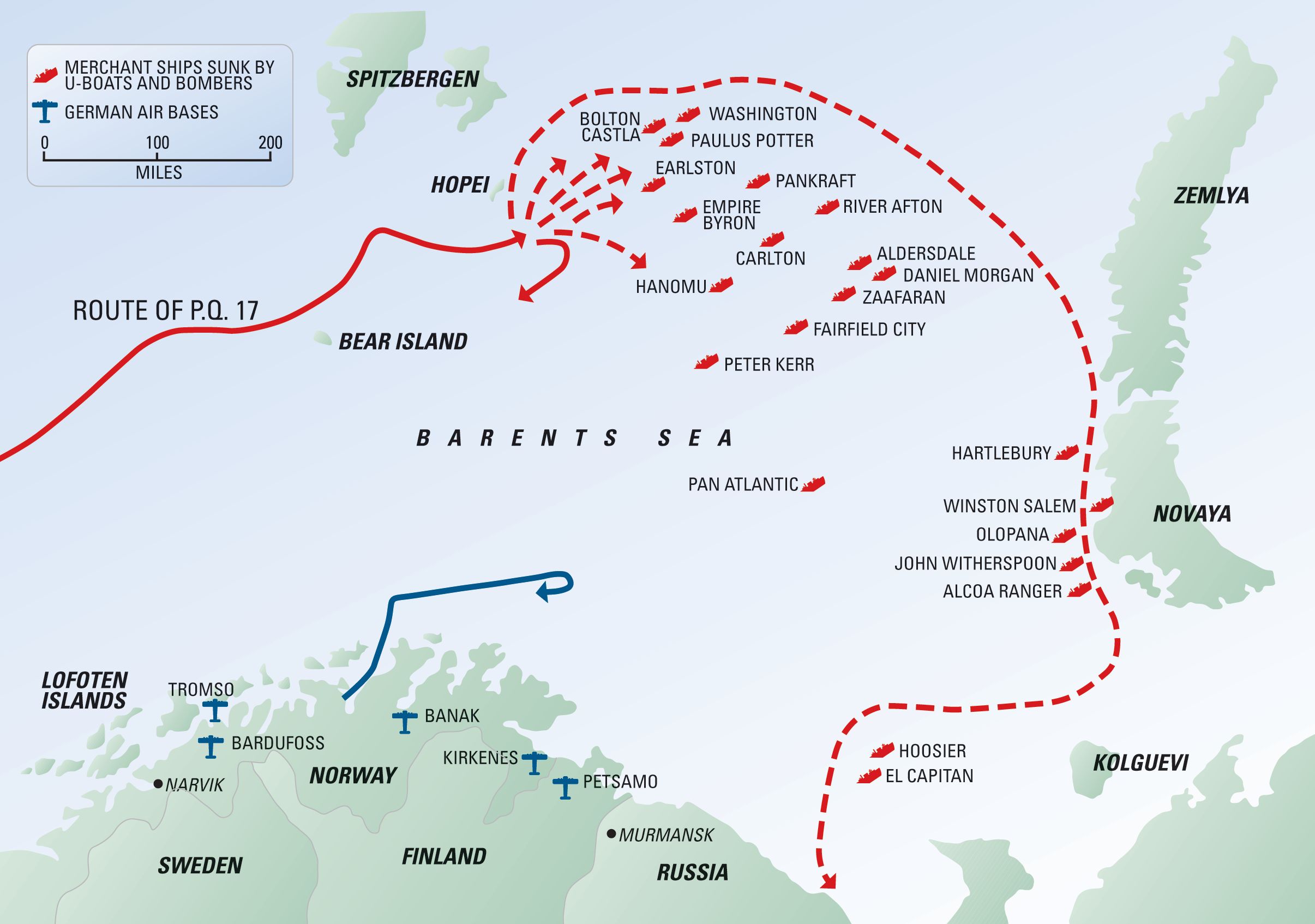

British Prime Minister Winston Churchill had made the promise to Soviet Premier Josef Stalin, and Admiral Sir John Tovey of the Royal Navy had to keep it: to sail three convoys loaded with critical supplies from Britain to Russia every two months, with 25 to 35 ships in each convoy. Now, on June 27, 1942, a total of 33 British and American merchant ships set sail from Reykjavik, Iceland, bound for the Soviet port of Murmansk through the icy, U-boat-infested Barents Sea. Convoy PQ-17 would sail into one of the greatest disasters and controversies of World War II.

By June 1942, the Allies’ fortunes were at their lowest ebb of the war. Rommel had reached El Alamein. Hitler’s panzers were advancing through Russia. Japan had conquered most of Southeast Asia and was taking dead aim at Australia.

Operation Knight’s Move

Stalin was the most desperate of the three Allied leaders that month. With Leningrad besieged, German tanks driving on his oilfields in the Caucasus, and most of his industrial regions in Nazi hands, he needed Allied supplies badly. Convoy PQ-17 would help to resolve that—its cargo included more than 300 tanks.

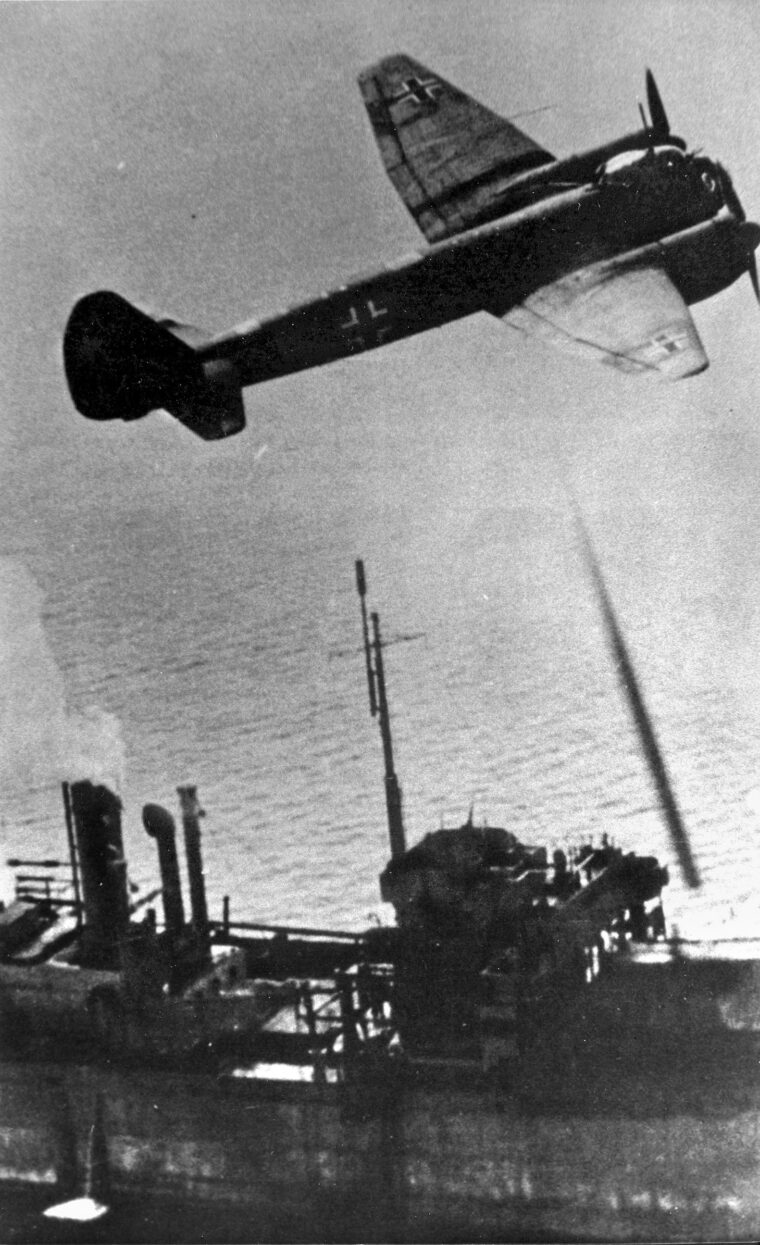

But the Germans were equally determined to stop the convoys, and from their Norwegian bases, they were well placed to do it. The primary tool was General Hans-Jurgen Stumpff’s Luftflotte 3, which consisted of 264 aircraft. The big punch was his 103 Junkers Ju-88 bombers, but he also had 42 Heinkel He-111 torpedo bombers and 30 Junkers Ju-87 Stuka dive-bombers. They were a veteran team that had already savaged British and American convoys to Russia.

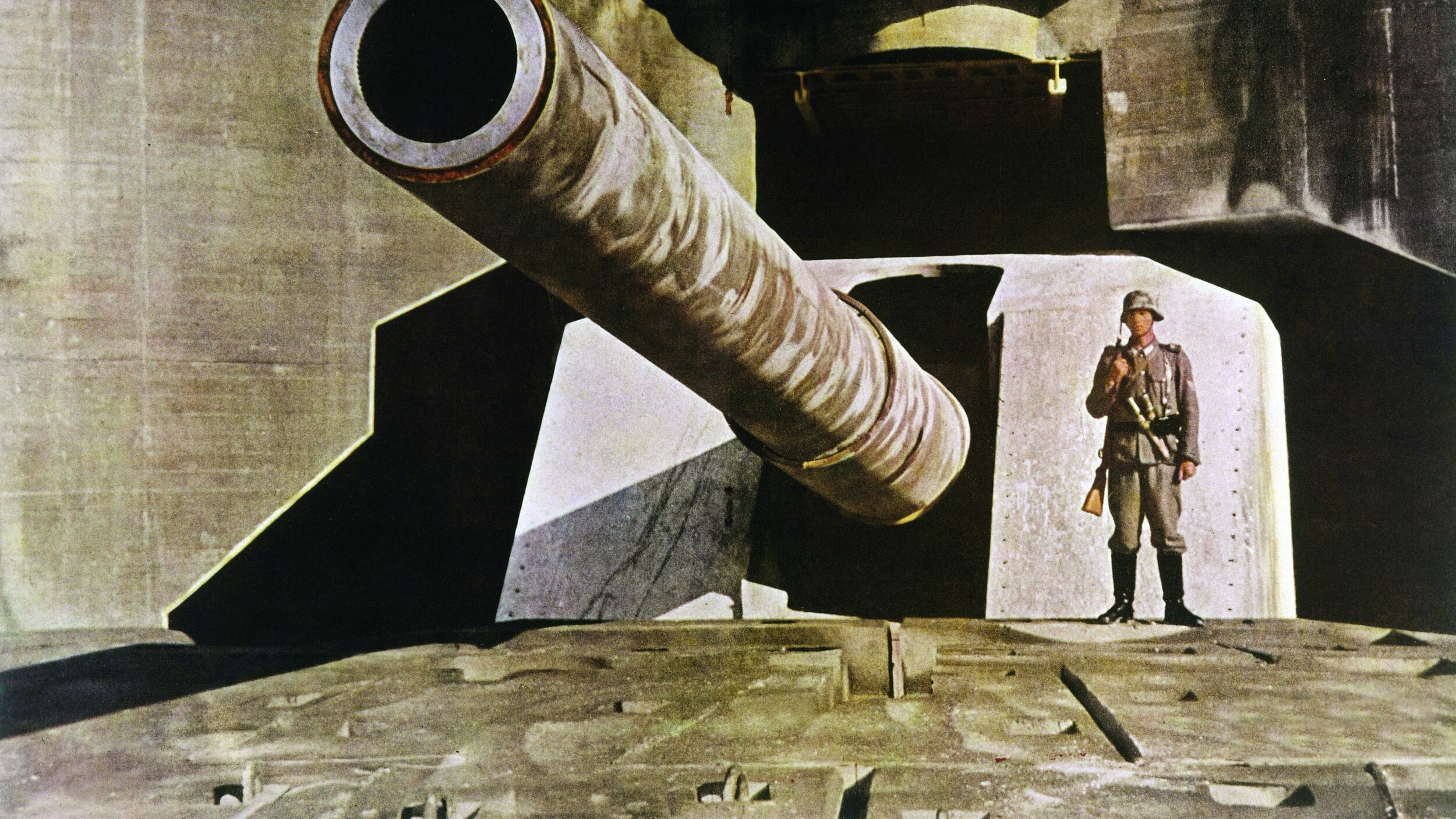

Also on hand were groups of U-boats to knife the convoys and track them, but the next convoy would face the biggest stick of all, the long-dormant German surface fleet, which had been unable to sail due to the perennial shortage of fuel oil. But 15,000 tons had just been allocated and delivered, and now the big ships could take part.

The German Navy planned Operation Rösselsprung, or Knight’s Move, which would see the super-battleship Tirpitz, the pocket battleships Lützow and Admiral Scheer, the heavy cruiser Admiral Hipper, and a brace of destroyers sortie from Altenfjord in Norway to attack the passing convoy as soon as it was located.

When Adolf Hitler read this ambitious plan, the man who admitted to being a coward at sea got cold feet. Yes, the fleet could sortie, but it could only engage if it had air superiority. After the Bismarck fiasco, he was not taking any chances with his precious battleships.

Supporting Convoy PQ-17

The British had a similar problem—they did not want to engage German surface ships without air cover. They decided that the convoy would only go straight through if the German ships were known to be in harbor or if the weather was bad. If the German ships sailed, the convoy would retreat or, at worst scatter, to avoid being caught all together.

The covering force for Convoy PQ-17 was a comprehensive group: three minesweepers, four trawlers, and a close escort group under Commander Jack Broome with six destroyers, four corvettes (one of them Free French), and two submarines. The only thing lacking was an aircraft carrier because most of the escort carriers that would make history had still not been completed. All Broome had for air defense was a single CAM Merchant ship, Empire Tide, with its lone Hawker Hurricane fighter. That plane could be launched off its catapult, but when out of fuel, the pilot had to parachute back—there was no possibility of recovery.

Broome was one of the Royal Navy’s more colorful characters, a witty cartoonist, and a skilled and resolute fighting sailor.

The close escort would be supported by a distant cover group, forbidden to go beyond Bear Island, under Rear Admiral Louis “Turtle” Hamilton, aboard the heavy cruiser HMS London. Accompanying him were the heavy cruisers HMS Norfolk, USS Wichita, and USS Tuscaloosa; it would be the first time Americans had directly participated in running an Arctic convoy. Beyond that would be Tovey’s main fleet, consisting of the battleships HMS Duke of York and USS Washington, and the aircraft carrier HMS Victorious, two cruisers, and 14 destroyers. Franklin D. Roosevelt Jr., son of the U.S. president, served as gunnery officer on one of the destroyers, USS Mayrant.

Meanwhile, PQ-17 got organized at Reykjavik with Commodore Jack Dowding in charge as convoy commodore, flying his broad pendant on the freighter River Afton. He told his ship captains that the convoy would be “no joyride,” but there would be cover from the British and American fleets. Dowding predicted that the convoy would get to Murmansk unscathed. Broome’s lecture, witty as usual, drew laughter and applause. The assembled captains were delighted.

That afternoon the convoy weighed anchor and headed to sea, picking up its escort; its destination was Archangel rather than the heavily bombed Murmansk. To deceive the Germans, Tovey sent out some minelayers to make feints. The deception failed. The Germans never spotted the minelayers.

“Ice Devils”

The Germans knew the convoy was coming anyway—they had cracked the British merchant ship code. First contact was on July 1, when U-255 and U-408 met up with the escorting destroyers, but Broome’s ships beat off the U-boats. That was all the Germans needed. They assembled a group of U-boats called “Ice Devil” and had them take up a patrol line across the convoy’s line of advance.

At noon that day the first shadowing aircraft arrived on the scene. The first air attack came that evening, when seven Heinkel He-115 seaplanes were vectored in by a shadowing seaplane and U-456. One aircraft was shot down by the destroyer HMS Fury. No damage was done in the attack.

By this time, Hamilton’s cruisers had overhauled the convoy and were standing away to the northward. Hamilton chose a parallel course to the convoy 40 miles away, out of sight of the shadowers, to keep the enemy guessing about his whereabouts.

PQ-17 was not the only convoy out there. Returning from Archangel, the 35-ship convoy QP-13 was also at risk. The British worried that the Germans might split their forces and hit both convoys. Hamilton zigged his cruisers around the sea, trying to keep within touch of the convoys and out of sight of the German snoopers.

With the British and Americans at sea, it was time for the Germans to move. The German fleet headed to sea and immediately ran into trouble in the form of uncharted rocks. One tore open the hulls of three destroyers, the Karl Galster, Hans Lody, and Theodor Riedel. The perennially luckless Lützow ran aground in Tjelsund and sustained severe damage. All four ships were out of the operation. The Germans concentrated their scattered ships at Altenfjord with orders to be ready to strike.

Independence Day in the Arctic Convoy

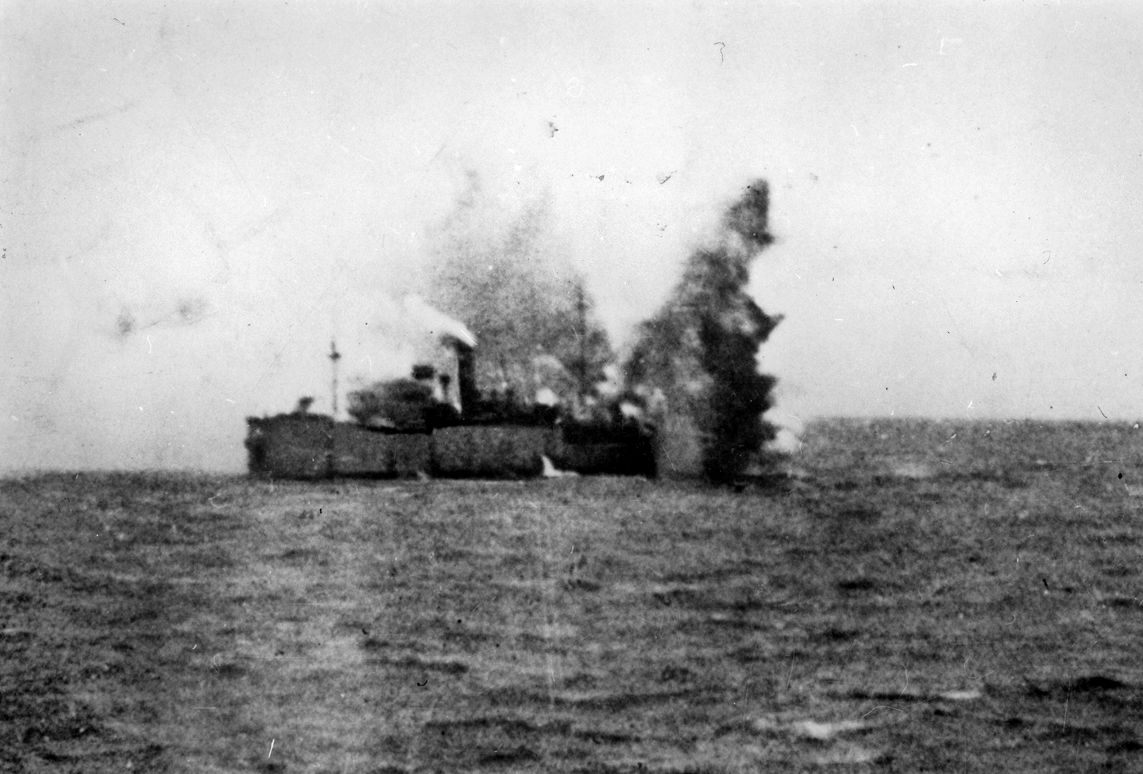

On July 4, the British ships of PQ-17 signaled “Happy Birthday” to the American ships, while the U.S. ships broke out their largest American flags to celebrate Independence Day. The same day, a single He-115 swooped down through the low cloud and torpedoed the U.S. freighter Christopher Newport. The crew was picked up, and Broome sent in the minesweeper HMS Britomart to investigate whether the ship could be saved. Britomart radioed at 5:20 am that the ship was flooded and her steering gear out of action. The British submarine P614 tried to sink her but failed, so the derelict was left behind and finally punched out by U-457.

Overhead, the Luftwaffe’s reconnaissance planes continued to shadow the British ships. It was the height of Arctic summer, with sunset lasting only a couple of minutes. A British destroyer signaled one of the German planes, asking if it could not “circulate in the other direction for a while, as we become dizzy.” The German signaled back, “Whatever it takes to please an Englishman,” and took up a reconnaissance orbit in the opposite direction.

Meanwhile, the multiple layers of British command were suffering from contradictory orders. The British deduced from their intelligence that the German warships would attack PQ-17 when it had reached a position between 15 degrees and 30 degrees East, which would occur sometime on July 4. London passed this news to Tovey with the order that Hamilton could, after all, take his cruisers east of 25 degrees East to support the convoy unless Tovey ordered otherwise.

Tovey saw this as London infringing on his operational and tactical command, and he ordered Hamilton at 3:12 pm to leave the Barents Sea unless he could be assured that Tirpitz was not at large. The signal crossed one sent by Hamilton at 3:20 saying that he intended to stay with the convoy until the German movements were clarified, but no later than 2 pm on July 5. Then at 6:09 Hamilton amended this and expressed his intention of withdrawing at 10 pm on July 4, after fueling his destroyers.

Meanwhile, the convoy plowed along. Fog cleared during the day, bringing excellent visibility, which enabled perfect formation. Broome remembered, “That morning stands out in my memory; in bright sunshine, a glass calm sea and except for the whining Blohm and Voss duet (the seaplane snoopers), peaceful. The air was crisp and brand new, the visibility back to phenomenal. Across the northern horizon was slung a weird-shaped lumpy line of vivid emerald green icebergs like chunky jewelry.”

“On to Moscow—See You in Russia!”

At 4:45 pm, to widen the gap between the convoy and the Luftwaffe air base, Hamilton suggested to Broome that the convoy alter course to the northeast. But the Luftwaffe was on its way. At 7:30, a single Ju-88 led a group of He-111 bombers from 1st Group, Kampfgeschwader (Bombing Group) 26, under Captain Eicke, in to attack.

The attack was foiled by the destroyer USS Wainwright, which had toddled over from the escort group to fuel from a convoy tanker. As Broome wrote in his report, “This ship lent valuable support with accurate long-range AA fire. I was most impressed for the way she sped round the convoy worrying the circling aircraft and it was largely due to her July 4 enthusiasm that the attack completely failed. One torpedo exploded harmlessly outside the convoy and two bombs fell through the clouds ahead of the convoy between Wainwright and [destroyer] Keppel.”

One German aircraft, flown by a Lieutenant Kanmayr, was lost in the attack, but the Luftwaffe pilot and his crew were picked up by the destroyer HMS Ledbury. They told the British that the Germans expected little resistance. Ledbury’s aggressive captain, Roger Hill, was very pleased with the situation.

As soon as this attack was broken up, in came a second group of He-111 torpedo bombers from the convoy’s starboard quarter. With Wainwright busy, the aircraft swooped to within 6,000 yards before dropping their fish. One hit the 7,200-ton American freighter William Hooper, and it began to settle in the water.

Another German pilot, Lieutenant Henneman, zoomed through AA fire and dropped his torpedo. It was intended for the freighter Bellingham, but instead hit the 4,800-ton British freighter Navarino under her bridge, and the ship took on a large list to starboard before being hit by a second torpedo. As Navarino sank, a Bellingham crewman heard a survivor, swimming in icy water yell, “On to Moscow—see you in Russia!”

Rescue ships sprinted over and picked up 49 survivors from Navarino and 55 from William Hooper.

The next victim was the Soviet tanker Azerbaijan, engulfed in a cloud of smoke. Everyone feared the worst, but she emerged from the smoke, still doing nine knots. Azerbaijan had a partly female crew, including a female boatswain, and rumors were that she was pregnant.

The Germans lost four planes in the raid, while wrecking two freighters beyond repair: William Hooper and Navarino. Both were ordered sunk. Nearby but out of range, Hamilton watched the whole show, impressed by the German courage and determination, less so by their inability to spot him.

Advance, Withdraw, or Scatter?

PQ-17 morale was now high—despite losing two ships, they were beating off the Germans with their concentrated anti-aircraft defenses. Broome was confident enough to write in his diary: “My impression on seeing the resolution displayed by the convoy and its escort was that, providing the ammunition lasted, PQ-17 could get anywhere.”

Meanwhile, at Altenfjord, the Germans awaited the decision to go. All they needed was clarification of the whereabouts of the British carrier, HMS Victorious. That evening, the British had their share of uncertainty as well. British code-breakers at Bletchley Park had not unraveled the German Navy’s new keys, and nobody knew when or if the Tirpitz and her reduced but powerful group would sail.

First Sea Lord Sir Dudley Pound, already ill with arthritis and the brain cancer that would kill him a year later, had to sweat out an agonizing situation … if Tirpitz sailed, it could not be opposed under German air cover. The convoy would have to disperse or even scatter to avoid being a single sitting duck for the dreadnought’s 15-inch guns. But where was Tirpitz? Had it sailed? Would it sail?

Pound finally asked, “Can you assure me that Tirpitz is still in Altenfjord?”

Operational Intelligence Center Commander Norman Denning answered that he was confident she was, meaning she was ready to sail out and attack but not actually at sea.

PQ-17 was then some 130 miles northeast of Bear Island, and a distance of 350 miles separated it from the guns of Tovey’s ships. If the two steered toward each other at best speed, they would be under cover of Victorious aircraft the following day, but it would slow the convoy’s voyage eastward and consume much fuel.

Another course was to order the cruisers to withdraw—since it now seemed probable that Tirpitz would attack—and rely on the close escort of destroyers, fog, bad weather, and British grit to fend off any German ships that attacked.

Finally, there was the possibility of ordering the convoy to simply scatter, which would make it impossible for the enemy to round up all the ships but also render individual ships nearly defenseless against attack.

“Convoy is to Scatter”

Pound now believed the worst—Tirpitz was at sea, streaking right for PQ-17. If that was the case, the convoy would have to scatter. Based on wholly negative evidence, Pound overruled his men in London and at sea. At 9:11 pm, he signaled, “Most immediate. Cruiser force withdraw westward at high speed.” At 9:23, he signaled, “Immediate. Owing to threat from surface ships, convoy is to disperse and proceed to Russian ports.” Then at 9:36: “Most immediate … Convoy is to scatter.”

The decision was an incredible gamble by an officer not on the scene. For the first time in the long and glorious history of the Royal Navy, a convoy was being ordered to scatter by an authority higher than the flag officer present at sea. It suggested that Tirpitz and her escorts were just over the horizon from PQ-17. It was a decision that historians would argue about for decades. Pound lacked actual combat experience. He did not discuss the situation with the leaders on the scene. He had no evidence Tirpitz was actually at sea. The order flew in the face of existing Admiralty policy. It ignored the great danger of U-boat and aircraft attack against scattered and defenseless merchant ships.

“It is not unjust to see in all of this a combination of Pound’s old-fashioned naval authoritarianism and his well-known stubborn closed-mindedness—coupled with that lack of imaginative talent which is the mark of great commanders,” assessed British historian Correlli Barnett.

The signal was received on Broome’s flagship, Keppel, with shock. Broome was furious. “I was angry at having to break up, disintegrate such a formation and to tear up the protective fence we had wrapped around it, to order each of these splendid merchantmen to sail on by her naked defenseless self; for once that signal reached the masthead it triggered off an irrevocable measure. Convoy PQ-17 would cease to exist.”

“Goodbye and Good Luck”

But Broome did not argue with his bosses. “I wish to make my appreciation at this moment quite clear. An order to scatter—especially when made most immediate by signal, following an order to disperse, thereby giving the impression of a situation developing rapidly—is in my impression, given when the threat is imminent, from surface forces more powerful than the escort. By imminent I mean that surface forces are in sight. We were all expecting, therefore, to see either the cruisers open fire, or to see enemy masts appearing over the horizon.”

HMS Keppel made the flag signal, and all the merchant ships signaled back with their flags at the dip, signifying, “I do not understand.” Roger Hill, on Ledbury, thought the message meant the Tirpitz was just over the horizon.

Broome took his ship into the convoy and re-signaled the order, adding radio and searchlights to drive the point home.

He closed Dowding’s River Afton and wrote later of his signal exchange with the convoy commodore, “We were not strangers. We had sailed together before, we respected one another. My visit and conversation were brief, for time was not for wasting. Naturally I put him in the picture as I saw it, and told him outright that I had faith in this order from the Admiralty. When I sheered Keppel away from River Afton, I left an angry and, I still believe, unconvinced Commodore.”

Broome signaled Dowding, “Sorry to leave you like this. Goodbye and good luck. It looks like a bloody business.”

Broome also had to figure out how to disperse his escort, which could not face Tirpitz either. The trawlers, minesweepers, AA ships, and corvettes could not stand up to Tirpitz, so they were ordered to head straight for Archangel. The submarines were ordered to act independently. The submarine P614 signaled to Broome that he intended to remain on the surface—if Tirpitz showed up, he hoped the sight of a submarine would scare the battleship off. Broome wittily answered, “So do I.”

On Ledbury, Roger Hill finally got the message. His crew was furious, but they obeyed the order, “revs up to 300, steer to the head of the convoy.” He assumed he was about to face the mighty Tirpitz.

Broome ordered his destroyers to hook up with Hamilton’s force, and Hamilton agreed. The tin cans tore away to the westward. On Ledbury, Hill sent his AA ammunition back down to the magazines and brought up the armor-piercing shot for his guns. He was ready to do battle with the Tirpitz, relying on his torpedoes. “Privately,” he wrote later, “I decided that if we ever got that far, we would go on and try to ram Tirpitz.” Then he piped, “Port watch to supper, 20 minutes.”

Broome and his ships and men were willing to take on Tirpitz, even in an unequal battle, doing so in reliance on their torpedoes and the best traditions of the Royal Navy. Everyone was ashamed at leaving the mostly American convoy in the lurch on Independence Day. As his ships steamed away from the merchant vessels, their crews let out cheers, also assuming the Britons were about to fight a major battle. Hill was stunned when he got his follow-up orders to close not with the enemy, but with the cruiser HMS London.

Hill wrote in his report, “It was now realized that we were abandoning the convoy and running away and the whole ship’s company was cast into bitter despondency.” Future Vice Admiral W.D. O’Brien, then a first lieutenant on the destroyer HMS Offa, wrote, “I have never been able to rejoice with my American friends on Independence Day, because July 4 is, to me, a day to hang my head in grief for all the men who lost their lives on Convoy PQ-17 and in shame at one of the bleakest episodes in Royal Navy history, when the warships deserted the merchant ships and left them to their fate. For that in simple terms was what we were obliged to do.”

Tirpitz Nowhere in Sight

As the escorts steamed off and the t-masts of the German ships failed to materialize, Broome and Hamilton were puzzled by Pound’s decision. HMS London’s crew was near mutinous. The escort ships entered heavy overnight fog, which cleared on the 5th, and Broome asked Hamilton if they should amend the orders and head back. No, Hamilton answered—their job was now to lure Tirpitz and her escorts within range of the battleships and carrier aircraft. Besides, the convoy had scattered—no point to going back to play sheepdog in the Arctic.

Scattering a convoy was not hard. Ships in the center column continued their course, ships in the column at either side of the center turned 10 degrees away from the center, ships in the next column 20 degrees, and so forth. The ships would then go to full speed and maintain constant radio watch, if not doing so already. After that, it was up to the individual ships. The merchant ships steamed off, with the escorts way ahead of them, protecting themselves if not the now defenseless convoy.

The Germans were stunned. At 1 am on July 5, Luftwaffe air reconnaissance reported the convoy spread over 25 miles. Admiral Hubert Schmundt, who headed Germany’s North Waters command, ordered in the “Ice Devil” U-boat group to concentrate on the merchant ships.

The U-boats wasted no time. At 7:15 am, U-703 torpedoed and sank the 6,600-ton British freighter Empire Byron, needing five torpedoes to do the job. Twenty minutes after taking her fatal hits, Empire Byron rolled over and sank, leaving 42 survivors in lifeboats, 18 dead. U-703 surfaced and her skipper took a British Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers officer, Captain John Rimington, aboard for interrogation, providing the remaining survivors with tins of biscuits, sausage, and apple juice before diving again.

At 10:15 am, U-88 disposed of the 5,100-ton American freighter Carlton with one hit, killing three men. The remaining 40 jammed the sole surviving lifeboat and four Carley rafts. The U-boat surfaced to report killing a 10,000-ton ship, leaving the survivors in their rafts on a glassy, calm sea. Later, German seaplanes alighted and took off 23 of the survivors and left the remainder gathered in one boat.

Meanwhile, Ledbury hooked up with HMS London and refueled from a tanker. While this went on, Hill told Admiral Hamilton that the captured Luftwaffe pilot had mentioned that Tirpitz was probably not at sea.

“I don’t think she is, either,” Hamilton said. Both officers were stunned by their orders.

“Abandoning Ship”

Mewanwhile, four merchant ships caught up with three escorts—an AA ship and two minesweepers—and clung to them for protection. This attracted a German reconnaissance plane, which sent out messages. However, the senior Royal Navy officer, Captain J.H. Jauncey of the AA ship HMS Pozarica, would not reduce speed, telling the merchant ships not to follow her. So the merchant ships headed for a fogbank.

At 3 pm, two merchant ships, the 7,200-ton Americans Daniel Morgan and Fairfield City, came under German Ju-88 bombardment. The Luftwaffe bombers plastered Fairfield City, sinking her and sending her cargo of tanks to the bottom. Daniel Morgan sped off to the east pursued by three lifeboats from Fairfield City.

Daniel Morgan evaded more Luftwaffe attacks through skillful ship handling, but it was not enough. Eventually a stick of bombs ruptured the plates between two of her holds, and she listed to starboard, steering gear out of action, and meandered about aimlessly.

U-88 had been stalking the Daniel Morgan all day with hydrophones, and now the submarine moved in. Two torpedoes in her port side, and Daniel Morgan was on her way to the bottom.

The 6,977-ton American Honoma was next. Pursued by U-334, she was torpedoed at 3:36. An explosion killed 19 members of her crew, leaving 34 in the water. Now SOS messages were flying in to the remaining ships, and the commander of the corvette HMS Lotus wanted to go back and render assistance. He asked Captain Jauncey of Pozarica for permission to do so, but Jauncey disagreed, saying, “I have been giving full consideration to this matter for half an hour and have come to the conclusion that the order to scatter was to avoid vessels falling into traps and unless you feel strongly to the contrary in the matter I think we ought to stick to our original arrangement.”

On Ledbury, the radio office kept passing up tragic messages from the merchant ships: “Am being bombed by large number of planes,” “On fire in the ice,” “abandoning ship,” and “Six U-boats approaching on the surface.”

Hill pondered quietly slowing down, turning back, and looking for survivors of the convoy. “I thought for months afterwards this is what I should have done. But discipline is strong, our orders were clear, we were miles away by then, and, the ever governing factor, almost out of fuel. We had been going full power for hours and burning eight tons an hour,” he wrote. “So, bitter, bewildered, tired, and utterly miserable, we stayed with the Admiral and the cruisers.”

Plummeting Morale

The attacks, the isolation, the cold were all breaking the morale of the merchant ship crews. On July 5, the crew of Samuel Chase abandoned ship on sighting a U-boat. The sub did not attack, and the crew simply reboarded their ship. Ironically, Samuel Chase survived the ordeal.

On the Alcoa Ranger, the crew saw a prowling aircraft and struck their colors, replacing them with the international signal for “Unconditional Surrender.” When the plane flew off, the captain reassumed command. The 7,200-ton British freighter Earlston, on the other hand, had sterner stuff at the helm. She fought off a chasing U-boat with her 4-inch gun, forcing her to submerge, thus ending the attack. She was ultimately sunk by U-334.

That evening, six more merchant ships met their end. First down was the Peter Kerr, overwhelmed by four Ju-88s from KG 30, which hit her with three bombs. The Bolton Castle, Paulus Potter, and Washington all hung together but found their way barred by ice. Eight Ju-88s from Captain Hajo Herrmann’s KG 30 swooped down and punched out all three—only the 7,200-ton Dutch Paulus Potter was left afloat as a derelict, to be found by U-255 on July 13. The Germans boarded the wreck and found the ship’s sailing orders, new signal codes for convoys, and other useful information.

Behind those three ships steamed the Olopana, which had slowed down to take on survivors, all from open boats. Amazingly, the shipwrecked sailors preferred their open boats to returning to a floating target.

One hundred miles south of the Bolton Castle group, the Luftwaffe pounded the rescue ship Zamalek, the freighter Ocean Freedom, the oiler Aldersdale and the minesweeper HMS Salamander. At 5:30 pm, four Ju-88s roared over and dropped bombs, which blasted open Aldersdale’s stern, wrecking her machinery. She had to be abandoned.

At the same time, the other rescue ship, Zaafaran, was sunk. Her skipper, Captain Charles McGowan, thought his ship could reach Novaya Zemlya on her own. He was wrong—Ju-88s pounded his ship and sank it anyway. Her survivors were picked up by Zamalek and hooked up with the Pozarica and two minesweepers to head for Novaya Zemlya.

Nearby, the freighter Earlston was hit by a lone Ju-88, which brought her to a halt. Like sharks thirsting for a kill, three U-boats glided in. Captain Stenwick abandoned the Earlston, and one torpedo put the freighter away. Stenwick himself was captured by U-334 and then had to endure the indignity of being a prisoner and the submarine being attacked from the air and damaged by a passing Ju-88.

14 Ships Sunk in 24 Hours

Distress signals were flying all over the place, and Lieutenant James Caradus on the Free French corvette La Malouine expressed the views of many, “Enemy torpedo planes were having a piece of cake on the scattered ships which were being attacked about 100 miles away. Complete destruction of the convoy is the German intention and we in La Malouine might have been able to help the odd merchantman but were too occupied protecting a well-armed anti-aircraft ship. A sore point with us all.”

HMS Lotus finally got permission to look for survivors and picked up 29 men from the sunken freighter Pankraft’s boats and then found survivors of River Afton, which was torpedoed around midday on July 5. Among the weary and cold men who had spent four hours on rafts was Commodore Dowding himself. He had just burned the last of their smoke flares.

In the first 24 hours after the signal to scatter, 13 merchant ships and a rescue ship had been sunk.

As July 5 turned to July 6, the first survivors of PQ-17 began to reach safe harbor at Novaya Zemlya. The AA ship Palomares, three minesweepers, and the rescue ship Zamalek, along with the Ocean Freedom got there first. Next came the other AA ship, Pozarica, La Malouine, and the corvette Poppy. La Malouine was sent back out to round up stray merchants and came up with four American freighters, Hoosier, Samuel Chase, El Capitan, and Benjamin Harrison. Soon enough, in came three more trawlers and the gallant Lotus, decks awash, jammed with 60 survivors from Pankraft and River Afton.

What of the Tirpitz? She was finally cut loose from her moorings on the morning of July 5 and immediately spotted by Captain Second Rank A.N. Lunin’s Soviet submarine K21, then the British submarine HMS Trident. The reports caused the German naval staff considerable anxiety. With their ships spotted, the advantage of surprise was gone. At 9:32 pm, the Germans recalled the Tirpitz, much to the crew’s disgust. Tirpitz had achieved her purpose without firing a single shot—as she did for most of the war.

Meanwhile, the U-boat and aircraft slaughter went on. Seven ships were strung out in an ungainly gaggle in the Northern Barents Sea, hugging the ice and making for Novaya Zemlya at best speed. Ju-88s and U-boats raced in to attack the Pan Atlantic, making a dash for the White Sea. A single bomb set off Pan Atlantic’s cargo of cordite, and she sank within three minutes, annoying the U-boat skippers who wanted a shot at the target first.

Six U-boats concentrated on this area, and one, U-255, sank the American ships John Witherspoon on July 6 and Alcoa Ranger the next day. Empire Tide, still carrying her Hurricane fighter, saw the sinking and maneuvered into Moller Bay and safety.

July 7 saw more sinkings with U-355 punching out the 5,100-ton Briton Hartlebury, and U-457 eliminating the derelict Aldersdale. It was enough for the skipper of the Winston-Salem, who ran his ship aground in Obsiedya Bay and set up camp in an abandoned lighthouse nearby.

“Three Ships Brought Into Port Out of 37”

In Matochkin Strait, Captain Jauncey of Pozarica, the senior officer, summoned the skippers of the various ships assembled there to plan their next move. The anchorage was too exposed. They had to break out. So on July 7, the 17 ships left the anchorage and headed south. One of them, Benjamin Harrison, lost her way and returned to the anchorage to try again. The ships managed a westerly course to find clear water, but not until July 9 could they head south again, amid clearing weather.

That morning first revealed two boatloads of survivors from Pan Atlantic, which were hauled in. Everyone kept an eye for promised Soviet aircraft. Instead, a German reconnaissance plane came in. They were spotted.

In the thin night and twilight of July 9-10, the Luftwaffe hurled 40 Ju-88s from KG 30. For four hours, the bombers plastered the merchant ships. The Hoosier and El Capitan were banged up by near misses and had to be abandoned. Poppy and Lord Austin picked up the crews, and rescue ship Zamalek had more than 240 survivors aboard. U-boats spotted the derelicts and torpedoed them later.

Now the Luftwaffe singled out Zamalek for more abuse. A watching British sailor said, “One stick of bombs actually took the Zamalek right out of the water so that you could see daylight between the keel and the water.” With her engines damaged from shock, the engineers turned to. Luckily, the ship had plenty of them from the various shipwrecks, and when she rejoined her group she was greeted with loud cheers.

Samuel Chase was also damaged and had to be towed by the minesweeper Halcyon. Finally, on July 11, Dowding led his ships through the White Sea into the port of Archangel. There he found the Soviet tanker Donbass and the American freighter Bellingham, which had arrived on July 9 along with the rescue ship Rahlin and the corvette Dianella. “Not a successful convoy,” noted Dowding bitterly. “Three ships brought into port out of 37.”

“Go to Hell!”

But there were still more out there. A second group of five ships was still heading in. Their survival was owed to Lieutenant J.A. Gradwell, who commanded the trawler Ayrshire. A peacetime lawyer, he had taken three freighters—Troubador, Ironclad, and Silver Sword—under his wing when the scatter order was given. Using the Troubador with her stiffened bows as an icebreaker, they steamed 20 miles into the ice, as far as they could go. That done, the crews painted their ships’ hulls white as much as possible, to blend into the bergs. For two days, the ships hid in the ice, listening to distant distress calls.

Finally, Gradwell broke out, and a high-speed dash took the ships to the north island of Novaya Zemlya on July 10. They hid there for 24 hours, then dashed down to the Matochkin Strait the next day. There they found the Benjamin Harrison, the Soviet tanker Azerbaijan, and icebreaker Murman. The Soviet trawler Kirov completed this colorful collection of ships.

Gradwell reported to Archangel, “The situation at present is that there are four ships in Matochkin Strait. My asdic is out of action and the Masters of the ships are showing unmistakable signs of strain. I much doubt if I could persuade them to make a dash to Archangel without a considerably increased escort and a promise of fighter protection in the entrance to the White Sea. Indeed, there has already been talk of scuttling ships while near shore rather than go on to what they, with their present escort, consider certain sinking.

“In these circumstances, I submit that increased escort might be provided and that I may be informed as to how to obtain air protection. I shall remain in the Matochkin Strait until I receive a reply.”

Dowding read this plea and set out with Lotus, La Malouine, and Poppy through the stormy Byelusha Bay to Novaya Zemlya. First the force found 12 exhausted survivors of Olopana. Poppy also found the American freighter Bellingham and signaled, “Do you want to be escorted?”

The Americans, angry, lashed back, “Go to hell!”

Poppy’s skipper, reading the message, said, “Can’t say as I blame him.”

Then they found Winston-Salem hard aground but with survivors of Hartlebury and Washington aboard. Dowding sailed on, looking for ships. He found the CAM ship Empire Tide, still with its Hurricane fighter, jammed with exhausted survivors, unable to move. Dowding split the Winston-Salem’s supplies with the Empire Tide and plowed on. Empire Tide made ready to sail.

Dowding arrived at Matochkin Strait on July 20 and transferred to the Soviet Murman, which would use her strengthened bows to lead the battered convoy home. They got out just in time. A day later a U-boat showed up at the Strait and found it empty.

Searching For Survivors

The convoy headed south and collected Empire Tide, while abandoning Winston-Salem. By July 22, the little convoy was augmented by the AA ship Pozarica, the corvette Dianella, three minesweepers, and best of all, two Soviet destroyers. All ships reached Archangel and safety on July 24.

Four days later, two Soviet tugs refloated Winston-Salem and dragged her to Archangel. That meant 11 of 33 ships had survived the bitter attacks on PQ-17.

Now came a search for lifeboats. Soviet and British planes based in Murmansk scoured the area. Dianella set out on the grim task after refueling in Archangel on July 9, returning on the 16th with 61 members of the crew of Empire Byron. Two of Alcoa Ranger’s lifeboats reached Novaya Zemlya while a third reached the mainland at Cape Kanin Nos.

Twenty-one crewmen from Honomu were very lucky as their lifeboat was spotted by warships just ready to turn about. Another lifeboat rowed 360 miles from the position where their ship was sunk to Murmansk. Two lifeboats from Bolton Castle reached the north Russian coast after dreadful fights between Arab and British seamen. Had they not come across an abandoned lifeboat from El Capitan loaded with provisions, they probably would not have survived. Another boat, from Earlston, landed in German-occupied Norway, where its six occupants became prisoners. Another boat with 17 survivors from Carlton also landed in Norway.

Of the 37 ships that sailed from Iceland, two had turned back, eight were sunk by air attack (40,425 tons), seven by U-boats (41,041 tons), and nine in combination of air attacks to damage them and U-boats finishing off the cripples (61,255 tons). Stores and equipment lost amounted to 430 tanks, 210 crated aircraft, 3,350 vehicles, and 99,316 tons of general cargo. A total of 153 merchant seamen (107 American) had lost their lives. Twenty-two of the 24 confirmed ships sunk were big freighters, 14 of them American. Of the cargo dispatched, the Soviets received only 896 vehicles, 164 tanks, 87 aircraft, and about 57,000 tons of military cargo.

In 202 dive- and torpedo-bomber sorties, the Germans had lost only five aircraft. Not one U-boat was sunk or damaged by Allied weaponry, but three U-boats took damage from friendly fire.

To make matters worse, the desperately needed supplies had failed- to arrive at a time when the Germans had launched a massive offensive on the southern half of the Eastern Front, which ripped through Soviet defenses in two weeks.

Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring, chief of the Luftwaffe, passed out three Knight’s Crosses to airmen who fought in the battle, and the Navy claimed that their 11 U-boats committed had fired 72 torpedoes, of which 29 had scored hits and exploded. Nine of the U-boats were credited with kills.

A Disaster For Allied Relations

On July 11, Admiral Sir Geoffrey Miles, head of the British Naval Mission in Moscow, had to explain the whole mess to Admiral V.I. Kuznetsov, chief of the Soviet naval staff. Kuznetsov was polite but his vice chief of staff hurled accusations of cowardice at the British.

In London, Soviet Ambassador Ivan Maisky demanded, with more nerve than tact, when the next PQ convoy would be sent. Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden said doing so would be futile at this stage. The Soviets were not pleased. Churchill and Stalin exchanged angry notes.

On July 28, an Anglo-Soviet inquiry convened in London to consider the affair. Eden, First Lord of the Admiralty A.V. Alexander, Pound, and Admiral H.G. Harlamov, head of the Soviet military mission in Britain, made up the guts of the panel.

The panel turned into arguments between Pound and Harlamov, with Pound yelling that if he, Harlamov, knew all the answers, then he, Pound, would ask the Prime Minister to make the Soviet the First Sea Lord in his place.

Pound as Scapegoat

On August 1, Pound briefed the Cabinet on what had happened. He told the Cabinet that his fear that Tirpitz was at sea had motivated his decision to withdraw. That did not correspond with the actual intelligence. Churchill tried to distance himself from the debacle then and later in his memoirs.

Next was to find a scapegoat. Despite arthritis and an incipient brain tumor, Pound was too high to be sacrificed. Instead, Hamilton was blamed, which was nonsense—he had followed his orders to the letter. Tovey wrote back, “The order to scatter the convoy had, in my opinion, been premature; its results were disastrous. The convoy had so far covered more than half its route with the loss of only three ships. Now its ships, spread over a wide area, were exposed without defense to the powerful enemy U-boat and air forces. The enemy took prompt advantage of this situation, operating both weapons to their full capacity.”

The key to the disaster was in Pound’s dogmatic and authoritative personality, but it was more than a case of a single man making a blunder. He was a highly competent administrator and dealt well with Churchill, but was not as competent operationally. The British system had put him at the top, and a system that could put Pound at the top was one that could, on such occasions as PQ-17, result in blunders.

Discontent Between the British Navies

Relations deteriorated between the Royal and Merchant Navies after PQ-17. There was considerable shame in the Royal Navy over what happened, and an effort was made to redress grievances. Admiral Hamilton “cleared lower deck” and explained what had happened to the outraged crew of his flagship, the London, telling them that his order to withdraw was based on higher powers’ decisions. Hamilton wrote to Tovey, saying, “It would have been a great assistance to me had I known that the Admiralty possessed no further information on the movements of the enemy’s heavy units other than I had already received.” He added, “Well, I suppose I ought to have been a Nelson. I ought to have disregarded the Admiralty’s signals.”

Roger Hill, back with Ledbury at Londonderry, Northern Ireland, had a few drinks with the skipper of HMS Offa, Alistair Ewing, to discuss the failure. “We discussed resigning, asking for an inquiry, defecting to the American Navy as Able Seaman, drank a lot of gin, and let off steam,” he wrote.

Instead, next day, Hill cleared lower deck and congratulated his crew on their AA gunnery and obeying orders, saying the entire affair had been an Admiralty fiasco, not theirs. In the future, he said, “We would do what we, on the spot, considered correct,” and then the ship sailed to Rosyth for boiler cleaning and five days’ leave for the men.

Also angry were the American sailors on the merchant ships, who unfairly labeled the British escorts as cowards who fled at the first sign of trouble. They may have fled, but not voluntarily—they had their orders. It would take a lot more convoys for the British to regain American respect. Another American officer who lost respect for the British was Admiral Ernest J. King, chief of naval operations, who ordered the American ships assigned to the Russian convoys and Task Force 99 withdrawn to the Pacific, a major gain for the U.S. Pacific Fleet, but a major loss for the overstrained Royal Navy’s Home Fleet.

“The Biggest Success Ever Achieved Against the Enemy With One Blow”

The Germans, of course, were elated by their victory. Stumpff wrote arrogantly to Göring, “I beg to report the destruction of Convoy PQ-17.” The war diary of the German Navy crowed, “This is the biggest success ever achieved against the enemy with one blow—a blow executed with exemplary collaboration between air force and submarine units. A heavily laden convoy of ships, some of which have been underway for several months from America, has been virtually wiped out, despite the most powerful escort, just before reaching its destination.

“A wicked blow has been struck at Soviet war production, and a deep breach torn in the enemy’s shipping capacity. The effect of this battle is not unlike a battle lost by the enemy in its military, material, and morale aspects. In a three-day battle, fought under the most favorable conditions, the submarines and aircraft have achieved what had been the intention of the operation ‘Knight’s Move,’ the attack of our surface units on the convoy’s merchant ships.”

Not so exultant were the crews of the German surface ships, who were upset at being out at sea for less than a day, then aborting their mission. One German officer wrote, “They should have let us make one little attack! Heaven knows, they could have always recalled us after we had bagged three or four merchantmen.”

Another officer wrote, “Here the mood is bitter enough. Soon one will feel ashamed to be on the active list if one has to go on watching other parts of the armed forces while we, ‘the core of the Fleet,’ just sit in harbor.”

At Best Premature, at Worst a Mistake

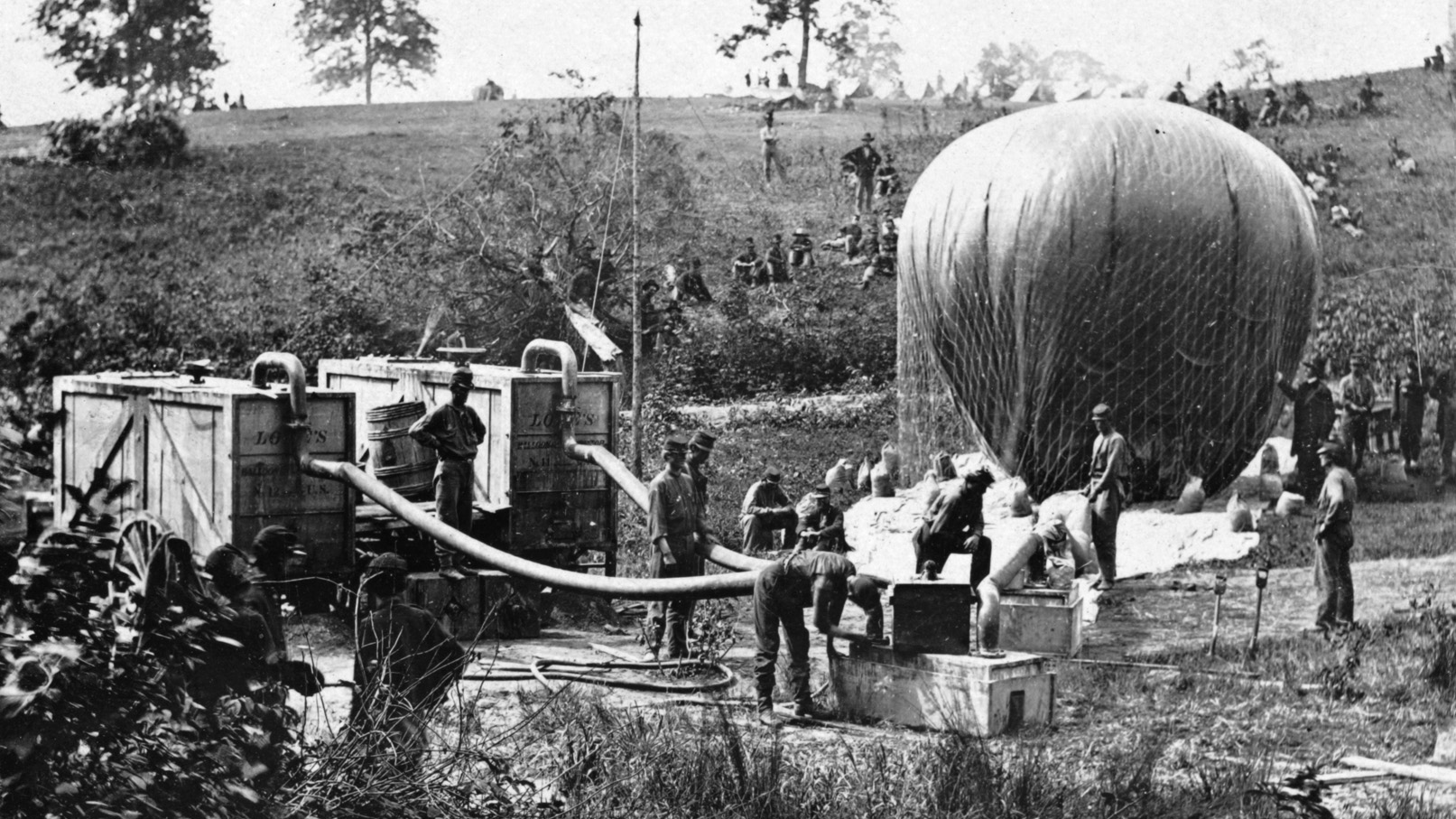

The British would launch one more convoy from Archangel to clear out the port and then cancel further voyages until autumn. When they resumed, the convoys would have more escorts, including aircraft carriers. Merchant ships would be equipped with more AA guns and tethered blimps and barrage balloons to ward off dive-bombers.

Historians agree that the scattering of the convoy was at best premature and at worst a mistake.

Roger Hill was blunt: “It is an extraordinary thing that this catastrophic error of judgment was made personally by the First Sea Lord, the Head of the Navy, Admiral Sir Dudley Pound. My personal opinion is that, if someone like Admiral Cunningham had been at the Admiralty, he would have left the people on the spot to run the operation. If not, he would have waited until the Tirpitz was reported and if she was obviously heading for and near the convoy, he would have signaled something like, ‘It is at your discretion to scatter should you be attacked by enemy surface ships.’”

Hill added, “I can never forget how [the merchant ship crews] cheered us as we moved out at full speed to the attack and it has haunted me ever since that we left them to be destroyed. I had little faith ever after in the shore staff who directed operations at sea.”

But the convoy could not have escaped heavy losses anyway. It lacked air cover, and U-boats and aircraft still would have savaged the ships had they remained tightly packed. But political expediency, the need to support the Soviet Union in its most dire hours, outweighed military realities. PQ-17 was a convoy that should not have sailed, but had to.

Such thoughts were far from the minds of the crewmen on the merchant ships that survived the ordeal and the survivors, huddling in blankets on the decks of rescue vessels. Morale was low.

On USS Washington, the battleship that had been called back instead of getting to fight the Tirpitz, Seaman 2nd Class Mel Beckstrand spoke up for most sailors about the back-and-forth decisions and the recall, writing home, “I wish someone would make up their mind. I would like to see an attack myself; it would break up the monotony. Everyone is gunning for Adolf, and we aren’t the least bit scared of him.”

Lieutenant-Commander Roger Hill got the opportunity to demonstrate his determination to defend the Merchant Navy barely two months later during Operation Pedestal. He took the escort destroyer Ledbury into the burning oil spreading over the sea from a sinking freighter to pluck the survivors from the flaming water.

Along with her sister ship Bramham and the fleet destroyer Penn, the Ledbury shepherded the heavily damaged tanker SS Ohio into Valletta, arriving on the festival of the island’s patron saint, Santa Maria. This is celebrated as the Miracle of Santa Maria because the merchant ships which survived the onslaught to reach the relative safety of Grand Harbour were the salvation of the besieged islanders. Original newsreel is used in the film, ‘Malta Story,’ to show the moving scene of the Ohio’s arrival. Two German bombers which were shot down by the escorts had crashed onto the tanker’s deck, rupturing barrels of high-octane avgas being carried as deck cargo. Despite this and extensive torpedo damage, enough of the cargo of fuel oil for ships, diesel for submarines and aviation spirit for aircraft, remained intact after the fires were extinguished and bulkheads shored up to keep Malta in the fight. This was vital for the submarines and bombers attacking Axis convoys to North Africa as it frustrated Rommel’s advance on Cairo in 1942.

In the film, the Bramham is seen still lashed to the port side of the Ohio. HMS Penn had been on the starboard side, holding the tanker together like splints on a broken leg with the Ledbury towing ahead to provide steering. The four ships were forced to sail at a snail’s pace, enduring repeated air-attacks, until they eventually limped into range of the island ‘s fighter cover.

The tanker broke in two and settled on the bottom shortly after mooring alongside the dock but her precious cargo of bunker oil and diesel was pumped ashore and the undamaged drums of avgas lifted off by crane to keep the RAF’s fighters and bombers flying.

Roger Hill’s memoir, ‘Destroyer Captain’, (often quoted in this article), provides a fascinating first-hand account of PQ17 and Operation Pedestal plus his later commands of the fleet destroyers Grenville and Jervis. Highly recommended reading for anyone interested in military history.

I have Roger Hill’s book, and referred to it in writing this article, as you note.

I wrote about Hill in another article on “Operation Pedestal.” Best book on that convoy has that exact title and is by Sir Max Hastings.

After the war and his Navy service ended, he had a hard time with his job interviews. Apparently his interviewers believed that the only thing a former Royal Navy Captain was good for was steering ships.