By Brig. Gen. (U.S. Army Ret.) Raymond E. Bell JR.

In his autobiography, War As I Knew It, Lieutenant General Patton set the tone for what was to become one of his Third U.S. Army’s infantry divisions’ major accomplishments in World War II. He stated: “I woke up at 0300 on the morning of November 8, 1944, and it was raining very hard. I tried to go to sleep but, finding it impossible, got up and started to read Rommel’s book, Infantry Attacks. By chance I turned to a chapter describing a fight in the rain in September 1914. This was very reassuring because I felt that if the Germans could do it, I could.…”

Patton’s army had been halted since early September by renewed determined German resistance before the eastern French city of Metz in the province of Lorraine. Efforts to capture the city and neutralize or destroy the ring of fortresses surrounding it had been in vain. On November 8, the beginning of a major coordinated effort by two U.S. Army corps to capture the city and fortification system which would open the way to the Rhine River, was the reason for Patton’s sleeplessness and his late-night reading of Rommel’s book.

First, Maj. Gen. Manton S. Eddy’s XII Corps launched its assault south of Metz early that morning. Then, before dawn the next day, elements of Maj. Gen. Walton Walker’s XX Corps crossed the Moselle River north of Metz and the neighboring city of Thionville, which culminated in what Patton was to label “an epic river crossing.”

German resistance to this major operation had previously proved successful in thwarting Patton’s attempts to capture the forts of a defensive system west of the Moselle River. Prominent among these operations was the unsuccessful attempt to capture the formidable and largely underground complex of Fort Driant located on the western approaches to Metz and which effectively commanded river-crossing sites south of the city.

The German Forces Opposing Patton

The German First Army was the principal enemy formation facing Patton’s two attacking corps. South of Metz and opposite Eddy’s XII Corps was the XII SS Corps’ 17th SS Panzergrenadier Division, an elite—at least in name—combat organization in the German Army. In Metz itself was stationed the 462nd Volksgrenadier Division under Generalleutnant Vollrath Luebbe. (He would suffer a stroke on November 12 and be replaced by Generalmajor Heinrich Kittel.)

To the 462nd’s north and covering a distance of some 20 miles to the small French town of Koenigsmacker was the 19th Volksgrenadier Division, which had been formed from remnants of the 19th Luftwaffe-Sturm-Division (19th Air Force Storm Division) in October 1944 and was led by the highly decorated Generalmajor Karl Britzelmayr.

The 19th Volksgrenadier Division was composed of three infantry regiments, the 59th, 73rd, and 74th. Each of these regiments consisted of two battalions, the 1st Battalion of the 74th forming the division’s right flank and manning Fort Koenigsmacker, which overlooked the hamlet of Basse Ham—not the fort’s namesake, the adjacent village of Koenigsmacker.

To the north of the 19th Volksgrenadier was the 416th Infantry Division, commanded by Generalleutnant Kurt Pflieger, with its organic regiments, the 713th and 714th. The seam between the 19th and 416th ran through Koenigsmacker village, which was later to have fire support implications for the German defense of Fort Koenigsmacker during the Third Army thrust over the Moselle River on November 9.

The combat effectiveness of these German formations varied widely. As expected, the 17th SS Panzergrenadier Division Götz von Berlichingen, under SS Gruppenführer Werner Ostendorff, stood as the most effective, although it, like most such organizations, lacked certain key elements, in this instance tank units. On the bottom rung was Pflieger’s 416th, which had arrived from Denmark at the beginning of October. Its role in German-occupied Denmark was that of static security. It had seen no combat and with its complement of elderly soldiers was regarded as best suited for strictly defensive battle.

Britzelmayr’s 19th Division had combat experience and, with about 5,000 soldiers, was between 80 and 85 percent of full strength. Its artillery complement consisted of a medium and two light battalions with an antitank element of 10 heavy weapons. The division’s subordinate units’ battle effectiveness lay somewhere between that of the 17th SS and 416th with varying degrees of competence depending to some extent on each unit’s access to fortress protection and fighting positions.

These German organizations were deployed in a defensive posture, which included manning forts reconditioned by the Germans during the time preceding Patton’s drive to finally capture Metz and its surrounding ring of fortresses. To the north of Metz and around the city of Thionville, the front line lay along the Moselle River which—at the time Patton awoke on the early morning of November 8—was at full flood stage.

Fort Koenigsmacker

It was this rain-engorged waterway that the U.S. XX Corps’ 90th Infantry Division, nicknamed the “Tough ‘Ombres” and commanded by Maj. Gen. James A. Van Fleet, had been ordered to cross and, in a northern pincer movement, meet the 5th Infantry Division’s southern pincer. The corps’ objective was to seal off and capture Metz with the ultimate goal of advancing east into Germany. Another American infantry division, the 95th, would also be employed in the battle. In addition, the 83rd Division’s artillery and the 10th Armored Division’s tanks would be available to support the assault.

The U.S. Army’s official history says, “The initial envelopment of the Metz area was assigned to the 90th Division, forming the arm north of the city, and the 5th Division, encircling the city from the south. The 95th Division was to contain the German salient west of the Moselle. Then, as the concentric attack closed on Metz, the 95th Division was to drive in the enemy salient and, it was planned, cross the Moselle and capture the city proper. The 10th Armored Division, after crossing the Moselle behind the 90th Division, was to close the pincers east of Metz by advancing parallel to and on the left of the 90th Division….”

During Patton’s major November 1944 northern thrust to envelope Metz’s fortress system, his 90th Infantry Division had one enemy stronghold obstacle to conquer: the formidable German-occupied Fort Koenigsmacker.

The fortress complex lay directly in the division’s path of the advance as the fort’s guns commanded the Moselle River’s crossing sites north of Metz and Thionville. U.S. Army Historian Hugh M. Cole noted in his volume of the Army’s official history, The Lorraine Campaign: “The tactical effectiveness of its location forbade that Fort Koenigsmacker be bypassed; it had to be taken and quickly.”

The 90th’s 358th Infantry Regiment, commanded by Colonel Christian H. Clarke, Jr., was charged with the critical mission of taking the fort, and the regiment’s 1st Battalion was specifically assigned the task.

Fort Koenigsmacker contained a battery of four powerful 100mm guns mounted in revolving ground-level armored steel turrets which, if properly manned and maintained, had the range to interdict military activity several miles in any direction. Although the gun line was oriented primarily to the north, the cannons could effectively bring fire to bear along a significant stretch of the Moselle River.

The fort was part of a longstanding defense network protecting the city of Thionville and the metropolis of Metz, both being surrounded by a number of elaborate fortifications. Some of the forts dated back to the time of the famous French military engineer the Marquis de Vauban (1633-1707).

The Germans constructed pentagon-shaped Fort Koenigsmacker between 1908 and 1915 when they occupied the French province of Lorraine following the Franco-Prussian War of 1870. After World War I, the fort and the province reverted to French control. When the French constructed the massive Maginot Line designed to stop an invasion from Germany in the 1930s, however, the fort was not considered an integral part of that elaborate defense system. Then, in 1940, the French lost the fort during the German invasion. In 1944, the Germans reactivated Fort Koenigsmacker to help stem the Allied advance into the Fatherland.

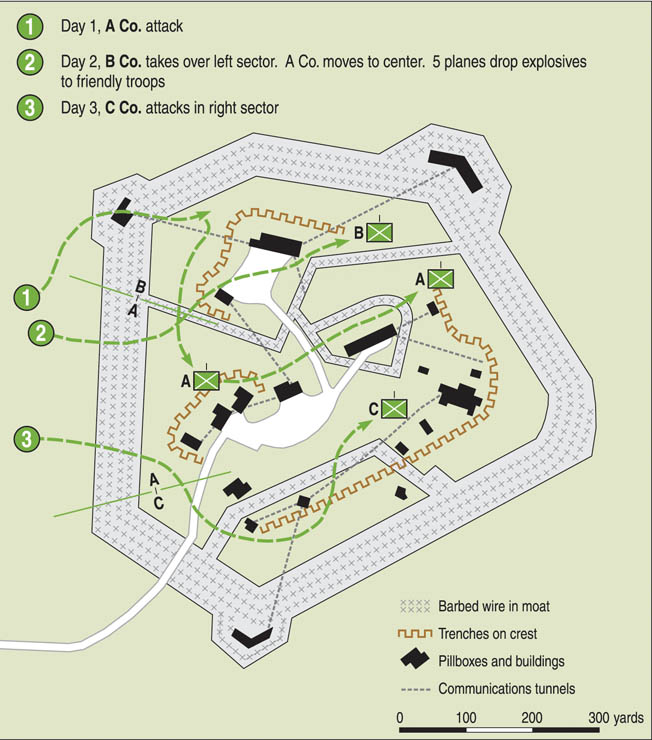

Besides the four-gun battery, the fortress contained three large blocks of underground living quarters, several scattered and protected shelter points, a deep moat on its eastern side fronted by a retaining wall, and armored steel observation posts with firing apertures for machine guns. Connecting the different parts of the fort was a system of deep underground tunnels lined with thick concrete. Numerous infantry fighting trenches around the various reinforced structures, zeroed in by mortars and artillery, encircled most of the top of the fortress. Dense thickets of barbed wire entangled the moats, which surrounded the complex and restricted movement within the fort’s confines.

Maintaining Operational Secrecy

In November 1944, Fort Koenigsmacker overlooked a swollen, swift, and turbulent Moselle River fed by heavy rainfall from watercourses throughout the region. On November 9, opposite the fortress, the river was almost a mile wide, partially flooding villages on its western bank. In some places the water was four feet deep—too deep for vehicle movement up to the river’s usual banks. A major impediment to even approaching the normal riverbanks was the mud.

Captain William M. McConahey, M.D., the battalion surgeon of the supporting 344th Field Artillery Battalion, noted, “The weather as usual was terrible—cold, muddy and pouring rain. The mud was worst of all. I knew how the infantry would be feeling [he had previously been a surgeon in the division’s 357th Infantry Regiment]. The miserable weather and the nasty job ahead would not make their lot easier.”

The Moselle River and its swollen banks north of Thionville thus represented a major obstacle to any military unit trying to pass over it and favored the defensive posture of the German troops on the river’s east bank and inside Fort Koenigsmacker.

A couple of high-water factors, however, were to favor the Americans’ initial river crossing. The surging water filled German foxholes and fighting positions strung out along the river’s banks, forcing the enemy to abandon them. In addition, the water’s depth at the crossing site was such that, until after the river crested, assault boats easily floated over the land mines laid along the shoreline. Only as the floodwaters receded did the mines become a hazard when the supporting engineers sought to bridge the river.

The 358th Infantry Regiment was just one of the 90th Division’s three regiments making the river crossing on the night and early morning of November 8-9. On the 358th’s left flank was the 359th Infantry, commanded by Colonel Raymond E. Bell, which was to make the crossing simultaneously with its sister regiment. Colonel Julian H. George’s 357th Infantry Regiment, initially held in reserve, was to follow closely over the river behind the two other regiments.

The plan for the 358th was for Lt. Col. Cleveland A. Lytle’s 1st and Lt. Col. Jacob W. Bealke’s 3rd Battalions to cross the Moselle abreast with the 3rd Battalion on the left and to launch its attack at 3 am on November 9 with the immediate objective of the village of Koenigsmacker and then advance eastward.

The 1st Battalion was to begin crossing a half hour later on the same day and capture Fort Koenigsmacker with Companies A and B while Company C secured the hamlet of Basse-Ham lying on the river in front of the fort. The regiment’s 2nd Battalion, initially in reserve, was to cross the Moselle River after a bridgehead had been secured and then take over the regiment’s left flank and advance eastward.

Success for the regiment, therefore, meant that the fort had to be captured—and quickly. The 358th could then advance with its two sister 90th Division infantry regiments in its thrust to meet up with the 5th Infantry Division beyond Metz.

Preparations to gain surprise and ensure the success of the river crossing by the 90th Infantry Division and supporting units were extensive. The division’s units had previously been engaged on the line opposite Metz and were withdrawn to a reserve position a week before the crossing was executed.

While there, key leaders surreptitiously conducted reconnaissance of the proposed crossing sites attired in clothing that did not identify them as members of the 90th Infantry Division. Division symbols on helmets were covered as was the number “90” on vehicle bumpers.

Special care was taken to see that the 90th Infantry Division shoulder patch was concealed from sight, especially from local people who might be German sympathizers. The division personnel conducting reconnaissance close to the river traveled in vehicles belonging to the 3rd Cavalry Group, which had long served along the Moselle, and the troopers’ movements were familiar to the Germans observing from across the river.

To conceal movement of division and supporting artillery into position from around Metz, the 23rd Special Troops deployed dummy rubberized artillery pieces and simulated explosive flashes to maintain the illusion of preexisting firing activity by artillery previously deployed.

Preparations for the operation by the 358th Infantry Regiment and its 1st Battalion after their relief from containing a portion of the sector around Metz began on November 3 when they moved into barracks near the town of Morfontaine. The first order of business was to rest, then to replace lost and worn-out equipment, and soon be outfitted with proper clothing and gear while assimilating new replacements. Then began an extensive period of training, briefing, and reconnaissance.

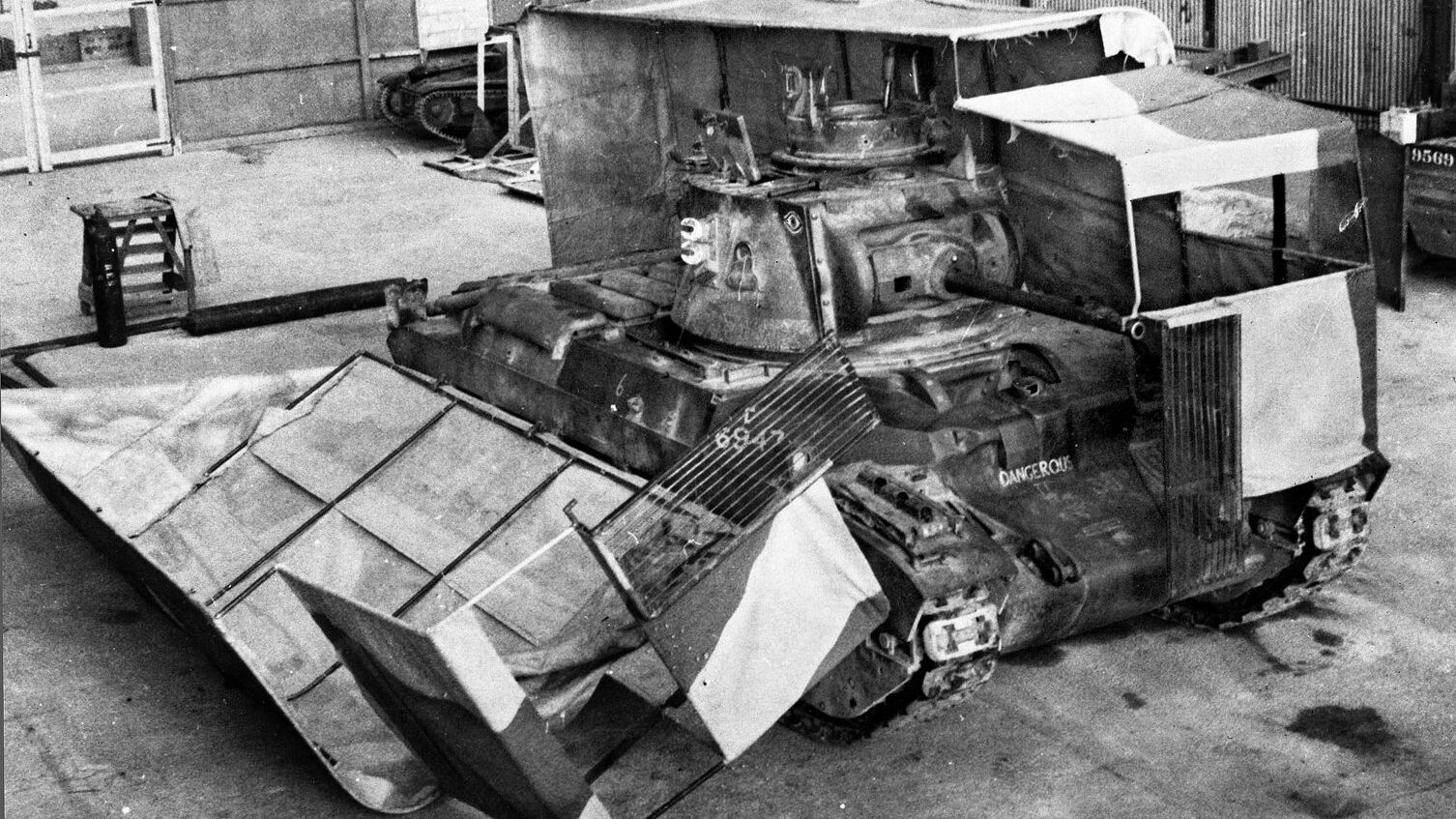

As background to preparations for attacking across the Moselle, and from the experience of such units as the 5th Infantry Division in trying to reduce, neutralize, and destroy the formidable complex of Fort Driant, a study was made about how to successfully attack Fort Koenigsmacker. Lessons learned from the inability to capture Fort Driant were applied to future operations. Possibly foremost of these was to avoid fighting within the labyrinths of the underground complex.

It was decided that it was sufficient to seal off entrances and escape routes while making it as difficult as possible for the fort’s occupants to direct supporting fire and launch counterattacks. This could be partly accomplished by targeting air ventilation and exhaust ports as soon as above ground observation and combat posts were destroyed or neutralized.

Ultimately, the fort’s garrison should be made to realize its situation was untenable and to surrender. Special attack techniques were developed and practiced with the realization that they would most probably be needed in the near future.

Preparing For the River Crossing

Before the soldiers could get to the fort, they had to get across the river, and this required special planning, training, and coordination with the supporting engineers. As it turned out for Lytle’s 1st Battalion, 358th Infantry, it would have been better if engineers from the division’s organic engineer combat battalion had been responsible for ferrying the men across the Moselle. That responsibility rested with soldiers from the attached 179th Engineer Combat Battalion, a Third Army engineer unit whose men were unfamiliar with the 90th’s organic 315th Engineer Battalion.

From October 3-7, the staff of the 1st Battalion carefully planned where and how to load the assault boats with which the soldiers were to be conveyed over the river. The infantrymen would pick up the boats at the hamlet of Husange, the closest place providing concealment for the engineer trucks carrying the boats to drop them off and from where they would be carried by the infantrymen and engineer crews to the riverbank. Detailed assignments to specific boats were made for each assaulting soldier, and attempts were made to have the 179th’s three-man engineer crews become familiar with their future passengers.

While the staff planned and saw that the troops were refitted and rested, the men themselves conducted intense river-crossing training on dry land. The battalion had not yet received a specified objective, although it was easy for its members to surmise that a river crossing and an attack on a fortress were in the forecast.

With that in mind, soldiers practiced carrying assault boats to the launch sites and then loading them properly in darkness under arduous conditions. The engineers who would guide and steer the boats showed the infantrymen effective paddling techniques and had them practice them as if the boats were already in the water. The men were instructed on how to conduct themselves in the boats and sit in them so as not to capsize them. They learned the different directions and commands that they would have to obey to ensure passage.

To preserve secrecy and achieve surprise, it was during the last moments that detailed reconnaissance and final coordination were executed down to the lowest unit level. Despite the tight time frame, there was hardly an individual soldier who was not thoroughly briefed on his forthcoming task when the operation began.

On November 7, just before the XII Corps offensive to the south began, the division produced maps, charts, aerial photographs, and large-scale engineer drawings, distributing them within the units to all personnel on a need-to-know basis. It was during the briefings that members of the 358th’s 1st Battalion first learned specifically that it had the additional difficult task of conquering Fort Koenigsmacker.

Headquarters officers briefed battalion leaders and key personnel, who then conducted reconnaissance in person as far as security allowed. By the time the operation was to begin, the entire command was well prepared for the coming action because planning, training, and coordination had been so thorough. The time allowed for the overall preparation activity and training had been unusually long—which frequently was not the case for such complicated and dangerous missions.

Lytle’s 1st Battalion and the rest of the 90th Infantry Division were, therefore, as well prepared for the river crossing, the attack on Fort Koenigsmacker, and the pincer movement as possible.

Taking the Enemy by Surprise

The 358th was to move into the nearby dense west bank in the Cattenom Forest the day before the crossing of the Moselle was to take place. Then, during the night of November 8-9, having advanced on foot to the hamlet of Husange on the outskirts of the town of Catternom, the 358th’s soldiers were to marry up with assault boats and carry them some 1,500 yards to the river crossing sites. Bealke’s 3rd Battalion was to push off first at 3:30 AM on November 9, while Lytle’s 1st Battalion was to follow in four waves of 40 assault boats each.

Carrying their boats, each crewed by three engineers from the attached 179th Engineer Combat Battalion, the heavily laden infantrymen struggled in the darkness along lines of tape laid by engineers to their launching sites through mud, muck, and water. Although cautioned to be silent to achieve a modicum of surprise as they moved forward, many of the struggling men still grumbled softly about their boat’s weight and the distance to their crossing site. The thick mud was especially enervating to the stumbling soldiers, and they arrived at the launching sites thoroughly tired, as well as wet from the continuing rain.

The infantrymen loaded as quickly as possible and then prepared to meet their next test. Because the flow of water was so swift and turbulent, it was with great difficulty that the companies gained the far shore. Slowly and quietly, however, the assault boats made their way across the river.

There were no shots fired as the craft floated over the abandoned German foxholes and mines submerged by the floodwaters. Battling the current, the engineers and infantrymen strained to bring their boats to the assigned landing sites, but the fast current carried many away from the intended dismount points.

As the damp and fatigued troops reached the far shore, they jumped into the mud and low water wary of any mines or other obstacles placed along the riverbank. Their wet boots and clothing added to their misery, but the soldiers pressed on in the darkness.

The 3rd Battalion’s luck ran out shortly after crossing the Moselle. Badly wounded in the hand, Lt. Col. Bealke returned to the battalion command post (CP) in Cattenom at 5:05 am and reported that the crossing had been undiscovered but not unopposed. Captain J.S. Spivey, an officer on Bealke’s staff, left the CP immediately to take temporary command of the battalion.

After the 3rd Battalion had crossed the Moselle, the 179th Engineers carried A and C Companies across the river in two waves with A Company on the left and C on the right; a platoon of engineers from the 90th Infantry Division’s 315th Engineer Combat Battalion accompanied the companies.

B Company crossed in a third wave, but because the corps engineer crews had unknowingly abandoned the assault boats they left it to B Company’s soldiers to row themselves across the river. The delay caused by the engineers’ error, however, did not change the plan to assault the fort. The infantrymen, nevertheless, would have preferred to have had division engineers, whom they felt were more reliable and attuned to core division values, manning the boats.

Once across the river the troops in the two companies destined for the fight for Fort Koenigsmacker struggled forward in small groups making for the railroad tracks and road which paralleled the Moselle. There, still undetected by the enemy, the companies paused, regrouped, checked equipment, took count of unit members, and then lined up for the assault on the fort.

The banks of the railroad line provided cover for these last minute preparations, and then the men crossed over the tracks and roadway. Leaving the cover of the railroad embankment, A and B Companies advanced toward the hilltop fortress, each in column formation with two platoons abreast. A Company advanced on the left with B Company on its right.

Luckily, the German soldiers on the east bank, having been forced from their foxholes and rifle pits and taken refuge in nearby houses along the river, were not in position to offer resistance. As a result, complete surprise was gained. The enemy troops in Fort Koenigsmacker were also unaware of the crossing and brought no fire to bear on the Americans as they advanced on their objective.

Meeting Resistance From the Volksgrenadier

The men entered the fields in front of the fort. It was tiresome work in a drizzling rain as they moved their way forward, looking cautiously for antipersonnel mines, especially the deadly ones that flung themselves into the air when detonated. None were found.

The fields beyond the road and railroad morphed into a wooded area where each company halted at the edge of the moat at the bottom of the hill where the fort was located. The men waited to cross at 7:15. A Company was pointed toward the northwest portion of the fort, while B Company headed to the west and southwest parts.

The woods and scattered trees had provided good concealment, allowing the two companies to approach the first obstacle, the moat heavily laced with barbed wire, unseen. With such protection the attached division combat engineers went to work cutting paths through the wire.

The moat in front of A Company was quite shallow, but much of the moat B Company had to cross was deep and wide with a concrete facing and filled with many coils of barbed wire. The task in front of A Company was accomplished relatively easily. The moat in front of B Company, however, soon proved to be an assault stopper.

At about the appointed time in the early morning twilight, A Company crossed the line of departure, moving through the wire and over the shallow moat. Cautiously the troops started up the moderately steep slope to the trenches located at the fort’s summit, which encircled the tops of the north and west concrete underground barracks.

The company’s 2nd Platoon remained at the bottom of the hill to neutralize an armored observation post and machine-gun position located there. The open trenches were unmanned, and the Germans in the observation post and machine gun position stayed silent.

It was not until A Company was on top of the barracks and into exposed German fighting positions that the enemy became aware of the Americans. Reaction to the presence of the A Company’s 2nd Platoon at the armored pillbox at the bottom of the hill, the remainder of A Company on top of the fort, and B Company hung up on the southwest moat was delayed but violent. A few German soldiers unexpectedly entered the trenches and opened fire on the advancing Americans. A close-in grenade battle ensued as the Germans sought to repel the attackers.

First Lieutenant Harris C. Neil, Jr., a platoon leader with Company A in the thick of the battle, remembered, “When my platoon reached the parapet [along the trench line], we surprised a group of Jerries. One jumped for a machine gun, and the sergeant killed him—fortunately. The others ran off down a trench and started throwing hand grenades at us. So for a little while we had quite a hand-grenade battle, mostly with us throwing their grenades back at them.”

Surprise having thus been compromised, prearranged German 50mm mortar and artillery fire directed from an enemy observation post was laid on the American infantrymen.

Fortunately, the 100mm artillery pieces in the fort could not lower their tubes sufficiently to fire on the attacking Americans, although German machine guns and mortars could. Actually, the fort’s artillery pieces never came into play; the artillery fire came from batteries located outside the confines of the complex.

The enemy garrison consisted of a battalion of the 74th Regiment of Britzelmayr’s 19th Volksgrenadier Division, one of the middling German infantry formations. Protected by thick underground concrete walls, the foe, once fully awakened to the presence of the Americans, launched scattered and vicious counterattacks. Erupting from openings in the interconnected tunnels, the Germans inflicted some 40 casualties on A Company in three morning forays. The enemy attacks, however, failed to dislodge the Americans from the top of the west barracks.

Neutralizing Fort Koenigsmacker

The solution to rendering the fort harmless lay with the use of explosives carried by the accompanying engineers from the division’s 315th Engineer Combat Battalion. They had brought satchel charges of C-2 explosive, which they knew from experience would be needed to win the fort. First Lieutenant William J. Martin’s engineer platoon and two specially assigned A Company assault teams aggressively went to work under intense German mortar and machine-gun fire.

The 17-pound satchel charges were first used to blow open the steel doors of German Shelter Point 3, located between the north and west underground barracks on the west slope of the fort. The point was quickly cleaned out and occupied, giving the assaulting troops a measure of cover from which they could go about the business of reducing the German resistance. The effort was then concentrated on the two armored observation posts on top of the two barracks.

The method employed by the assault teams was a coordinated move by an engineer with a satchel charge and an infantryman, who would quickly rush an embrasure, door, or sally port. Under covering fire from the other team members and close-in fire support from the soldier with the engineer, the explosives were put in place, a short fuse was activated, and the two men swiftly retreated to cover.

The explosion did not necessarily destroy the target but instead stunned its occupants senseless, effectively neutralizing them, or in the case of a steel door, blasting it open and thereby clearing the way to a staircase leading to rooms and galleries below. As a followup, the troops then threw additional charges down the staircases to kill the foe, to block enemy access to the surface of the fort’s underground structures, and to allow penetration of the fort’s inner works.

By the end of the first day, the northwest pillbox at the base of the hill had been put out of action by the 2nd Platoon of A Company, which had then advanced toward the top of the north barracks. That platoon was later replaced by the 1st Platoon, which moved over from the top of the west barracks. The 2nd and 3rd Platoons then occupied the trenches around the armored observation post on top of the west barracks.

That day a third of Fort Koenigsmacker was occupied by A Company, but the cost had been high with 40 American casualties. Also, B Company had not succeeded in getting over the moat and through the wire. The resupply of ammunition and explosives was hindered both by German artillery and the rapidly flowing Moselle River.

Resupply by Air

November 10 saw more of the same fighting to knock out the enemy, while during the night B Company had been withdrawn from in front of the wire-filled moat and moved around to A Company’s left flank on top of the fort.

The depleted supply of C-2 explosive called for another innovation to get at the German defenders deep in their underground quarters. The point of the American attack shifted in part to the ventilation ports atop the barracks. Lieutenant Neil came up with the idea of pouring 10 gallons of gasoline down a porthole and then igniting the fuel with a thermite grenade. This form of attack proved to be lethal and psychologically damaging to the Germans deep inside the concrete structures. During one such attack a German soldier was blown to the surface of the fort by the explosion’s force.

By noon on November 10, all the armored observation points on the top of the fort in A and B Companies’ sectors had been knocked out, but a new factor came seriously into play as the day progressed, the shortage of C-2 explosive. The resupply of everything across the Moselle River was severely interdicted by German mortars and artillery, which continued their effective fire on the crossing sites. In the case of the C-2 resupply, the remedy was to employ the 90th Infantry Division artillery spotter and liaison aircraft to fly close to the fort and air-drop the needed additional satchel charges to the infantrymen.

One pilot, 1st Lt. Lloyd A. Watland, was sent to discover the best approach by air to execute the resupply drop. Deliberately attracting enemy fire to disclose the positions of the antiaircraft guns, he flew as low as 10 feet above the ground to chart a reasonably safe route for the other pilots to follow over the fort. He was successful in accomplishing his dangerous touch-and-go reconnaissance mission and later received the Distinguished Service Cross for his selfless and daring action.

Following Watland’s path, five liaison aircraft, each carrying 100 pounds of C-2 explosive, flew over the fort. Under enemy fire they dropped their loads precisely. This gallant effort and successful mission enabled the troops on the ground to continue to attack, and by nightfall they were well established on the west side of the fort.

That same day, C Company, having turned over its sector in Basse-Ham to other 1st Battalion elements, joined the other companies and moved to the northwestern sector of the fort.

The day’s fighting had achieved slow but steady progress. The tired Americans, however, were now fighting a German force that continued to fight even more stubbornly than the day before. A German counterattack of 50 men late in the evening, which had temporarily cut off one of A Company’s platoons, was met by a determined C Company assault and thrown back with the loss of 28 Germans killed.

Still the enemy persisted and the weather continued to take the side of the fort’s defenders. German fire on the crossing sites and roads below the fort also continued to hamper resupply and evacuation of wounded; essential commodities were in short supply. However, by the end of the second day the 1st Battalion had blown open and secured lodgment in two tunnel entrances. As the other battalions of the 358th Infantry Regiment bypassed the fort and advanced eastward, however, it began to look like trying to capture the fort was not worth the effort.

“This Fort Is Ours”

On the third day, November 11, with most of the fort now in the battalion’s hands, the three companies prepared to make a final attack at noon. Shortly before the attack began, the 90th Division sent a message to headquarters of the 358th Infantry that its 1st Battalion should be withdrawn from the fortress complex.

The regiment then sent the withdrawal message to the fort, where it was received by Lieutenants Neil and Ross of A Company who were standing in a recently captured tunnel and assembling a group of volunteers to make an assault on the fort’s main entrance. Neil and Ross conferred and quickly agreed they were not going to heed it. They might well have done so because the 2nd Platoon was down to eight effective soldiers and the 3rd Platoon had only 13 men counting the slightly wounded. They knew that their force was not large enough to tackle the guts of the fort.

Neil, however, recalls that with Ross’s agreement he composed and scribbled a note to battalion headquarters that read, “This Fort Is Ours—until my platoon is down to two men. Then and only then will we retire. I could not ask my men to leave now. They are more determined than I to finish the job.” The final attack went forward.

Individual acts of bravery were common that day. B Company’s Pfc. Warren D. Shanafelter, for example, volunteered to silence a troublesome concrete pillbox. While enemy fire kept his fellow soldiers down, he got to his feet with a satchel charge, calmly rushed the structure, and set off the explosive. He rushed inside, killing or wounding the occupants.

American help then came from an unexpected quarter as the Germans sought to reinforce their beleaguered garrison. The 3rd Battalion, 358th Infantry Regiment had managed a painful move under enemy artillery fire around and beyond the north side of the fort.

The battalion had established a position on the Bois d’Elzange Ridge, whereupon K Company intercepted a three-man German patrol making its way toward the fort along a back road. Swift interrogation of the captured enemy soldiers revealed that a relief column of some 150 men was en route to the fort along the same road. First Lieutenant Frank E. Gatewood, the K Company commander, quickly deployed his five light machine guns to set up an ambush. At a range of only 50 yards, the Americans opened fire on the stunned foe, over half of whom were quickly killed. The remainder fled.

In the meantime, G Company of the 2nd Battalion had come to the fight. It entered the battle attacking the fort from the east, encircling the enemy garrison. The company proceeded to reduce two pillboxes and forced entry into the fort, closing off the eastern tunnel exits.

At 4 pm, as G Company and A Company squeezed the Germans between them, the enemy attempted a mass breakout through one of the shelter points on the northeast side of the fort. Unfortunately for them, the German soldiers ran right into the attacking G Company, which quickly rounded up the survivors.

The German commander had had enough. It was time for him to bow to the inevitable and surrender the fort’s garrison. He sought out the commander of G Company and presented his pistol to him. The two officers carrying the white flag of surrender then entered a gallery, passing dead and wounded German soldiers. They made their way toward the other side of the fort, where A Company was still fighting and blowing up doors and gun apertures.

At one entrance an explosion knocked the two officers to the ground, and the company commander reputedly grasped the white flag, struggled to the entrance, stuck the flag out so the A Company men could see it, and called out to cease firing as the fort was theirs.

The cost of the fight to the 358th’s 1st Battalion was high; 111 American soldiers had been killed, wounded, or had gone missing. This did not count the many casualties at the crossing sites of the Moselle among those soldiers trying to reinforce and resupply the men at the fort. On the other hand, although official accounts differ, as many as 372 German soldiers were captured and many more—perhaps as many as 128—of the enemy were killed.

Still, the Germans did not give up easily. Following orders for a counterattack, on the night of November 11-12, Generalleutnant Paul Schurmann’s 25th Panzergrenadier Division, which had been nearly destroyed in fighting on the Eastern Front and had been recently reconstituted at the Baumholder training area, supported by 10 tanks and assault guns, attempted to take back the fort, striking at the 359th’s positions at the village of Kerling in an attempt to reach Petite-Hettange and the bridge site at Malling.

As the U.S. Army’s official history of the Metz campaign noted, “The first clash came when the enemy hit G Company (1st Lt. A.L. Budd) and two platoons of the 2nd Battalion heavy weapons company (Captain S.E. McCann) deployed in the woods south of the road. A part of the German column turned aside to deal with these forces; a part continued on toward Petite-Hettange. The mortar and machine gun crews supporting G Company especially distinguished themselves in the action which followed.

“Sgt. Forrest E. Everhart, who had taken over the machine gun platoon when the platoon commander, 1st Lt. William O’Brien, was killed, led his men with such bravery as to be awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor. Private Earl Oliver stayed with his machine gun when the other guns had been knocked out, and maintained a continuous fire until he was killed by a mortar shell. When day broke, 22 enemy dead were found in front of his position—some only 15 feet away. So close had the Germans pressed the assault that a sergeant in the mortar platoon had uncoupled the bipod of his mortar and used it at point-blank range. Although G Company was cut off, the attackers could not overrun its position, and they finally were driven off when the American gunners west of the river laid down a box barrage.”

Eventually, the German counterattack against the 359th petered out. Fort Koenigsmacker and the surrounding territory were firmly in American hands.

Conquering Koenigsmacker was a minor victory for the 90th Infantry Division and Third Army in the context of the division river crossing characterized by General Patton as “epic.” For the soldiers and officers of the 358th Infantry Regiment, especially the regiment’s 1st Battalion, it was a major episode in their distinguished World War II battle history.

The fight for the fort is enthusiastically remembered in eastern France by both the liberated French and the American veterans who fought there. The French Moselle River 1944 Society makes an effort every five years to ensure that the American sacrifices at the fortress are not forgotten, even as the World War II veterans slowly go to their just final reward.

I am a subscriber to your magazines

My father was a scout in 106 CAVALRY RECON he was part of this .